Omniscience and free will

The major monotheistic traditions in the west hold that God is omniscient. Not only does God know everything there is to know about the past and the present, but God also knows everything there is to know about the future. For some, this includes knowledge of future human actions. Take, for example, a passage from the New Testament:

Jesus was troubled in spirit and testified, ‘Very truly I tell you, one of you is going to betray me’. His disciples stared at one another, at a loss to know which of them he meant … leaning back against Jesus, [\,John] asked him, ‘Lord, who is it?’ Jesus answered, ‘It is the one to whom I will give this piece of bread when I have dipped it in the dish.’ Then, dipping the piece of bread, he gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot (John 13:21–26, New International Version).

Evidently Jesus (who, in the Christian tradition, is identical to God) has knowledge of Judas Iscariot’s future act of betrayal.

Does Jesus’ knowledge of Judas’ future action have any implications about Judas’ freedom regarding this action? Some have thought that Jesus’ knowledge makes it impossible for Judas to have free will concerning his betrayal. Because Jesus knows what Judas will do (and Jesus can never be wrong about what he knows) Judas will not be able to do anything other than act in betrayal. We might call this view incompatibilism since it claims that Jesus’ knowledge (i.e. divine omniscience) and human free will are incompatible with each other. Others have thought that Jesus’ knowledge still leaves room for Judas to have free will concerning his betrayal. We might call this view compatibilism since it claims that Jesus’s knowledge (i.e. divine omniscience) and human free will are compatible with each other.

The debate over the relationship between omniscience and free will has been alive and well for centuries. Here, for example, is Boethius, a Roman thinker from the early middle ages (fifth to sixth century):

I don’t see how God can have foreknowledge of everything and that there can still be free will. If God sees everything that will happen, and if he cannot be mistaken, then what he foresees must necessarily happen. And if he knows from the very beginning what all eternity will bring, not only men’s actions but their thoughts and desires will be known to him, and that means that there cannot be any free will (Boethius Reference Slavitt2008, 151–152).

And there is no sign the debate will end any time soon. Nelson Pike (Reference Pike1965) often gets credit for forcefully presenting the tension between omniscience and free will in a way that has generated a massive recent literature. The idea behind Pike’s argument is that past events cannot be changed because they are, so to speak, ‘over and done with’. We might call this claim the fixity of the past (FP). Now consider a belief that God had in the past as a result of his omniscience. Perhaps God had a belief (B) at some time in the past that Paul will not mow his lawn next Saturday. Because God’s believing B happened in the past, given FP, God’s believing B is now a necessary feature of the past. Moreover, since God can never be wrong about what he believes it seems that B must be true – Paul will necessarily not mow his lawn next Saturday.

But then it seems Paul does not have the ability to do otherwise. After all, it’s a matter of necessity that he will not mow his lawn next Saturday. If having the ability to do otherwise is necessary for free will then Paul will not freely refrain from mowing his lawn.

Arguably the most influential response to Pike’s argument is known as ‘Ockhamism’. The Ockhamist response turns on a distinction between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ facts. A hard fact is a temporally non-relational, intrinsic fact about a time. A soft fact, on the other hand, is a temporally relational, extrinsic fact about a time. Consider the following examples.

(1) The doorbell rang at 7 am.

(2) The doorbell rang two hours prior to my typing.

(1) is a hard fact about 7 am. It is not related to any other time. The doorbell ringing is over and done with at 7 am. In contrast, (2) is a soft fact about 7 am. It is not over and done with at 7 am because it involves facts about times other than 7 am.Footnote 1

Armed with the hard-soft distinction, Ockhamists argue that some of God’s beliefs (e.g. B) are not hard facts about the past. Instead these beliefs are soft facts about the past since they involve facts about a future time. As such, they are not subject to FP. FP, Ockhamists claim, only applies to hard facts about the past. Consequently, though God’s belief in B is in the past, because it depends on Paul’s future action, God’s believing B is not necessarily over and done with – it is not fixed. It’s possible, based on what Paul will do (i.e. mow his lawn), that God had never believed B. So the Ockhamist can argue that Paul has the ability to do otherwise despite God’s omniscience.

Alvin Plantinga (Reference Plantinga1986) pointed out, however, that even if the Ockhamist has a way of reconciling omniscience (rendered as soft facts about future human actions) with free will, the Ockhamist faces other consequences. He offers the following scenario to illustrate such a consequence:

Let’s suppose that a colony of carpenter ants moved into Paul’s yard last Saturday. Since this colony hasn’t yet had a chance to get properly established, its new home is still a bit fragile. In particular, if the ants were to remain and Paul were to mow his lawn this afternoon, the colony would be destroyed. Although nothing remarkable about these ants is visible to the naked eye, God, for reasons of his own, intends that it be preserved. Now as a matter of fact, Paul will not mow his lawn this afternoon. God, who is essentially omniscient, knew in advance, of course, that Paul will not mow his lawn this afternoon; but if he had foreknown instead that Paul would mow this afternoon, then he would have prevented the ants from moving in.

According to this scenario the ant colony has already moved into Paul’s yard. This seems to be an uncontroversial hard fact about the past if anything is to be considered a hard fact about the past. Nevertheless whether the ants are in Paul’s yard depends (via God’s ability and desire to protect the ants) on Paul’s future action. So it seems, contrary to Ockhamism even hard facts about the past may not be subject to FP.

To summarize this all too brief discussion we might say there are at least three views on the table. One view is incompatibilism. It states that the past is fixed tout court. God’s past beliefs, simply because they are in the past, are unchangeable features of the past. Some of these past beliefs are about the future (e.g. God’s belief that Paul will not mow his lawn). Because these beliefs are unchangeable they constrain what can and will happen in the future (e.g. Paul will necessarily not mow his lawn and is therefore not free with respect to this behaviour). The other two views are forms of compatibilism and they involve ways in which the past might have been different than it actually is. Ockhamism states that only hard facts in the past are fixed. We might call this claim the fixity of the hard past. Because God’s past beliefs about the future are not hard facts, they are not fixed and therefore might have been different than they actually are. As Plantinga pointed out, however, it seems that certain hard facts about the past can nevertheless depend on future events and cause problems for Ockhamism. The third view, which we’ll call dependence theory, avoids this problem by claiming that the hard/soft distinction is irrelevant in terms of determining whether a given fact in the past is fixed. What matters is whether a given fact in the past depends on the future. Only facts in the past that are independent of the future are fixed. We might call this claim the fixity of the independent past.

These are fascinating ways of making sense of the relationship between omniscience and free will. What interests us in this article, however, is not so much the views themselves, but the way that intuitions have figured prominently in justifying these views. Here is a small sampling of passages that highlight such intuitions:

I simply find the fixity of the hard past extremely plausible; it is, no pun intended, hard for me to jettison this highly intuitive picture … I just do not see how it is plausible that [Paul] has access this afternoon to a possible world in which the ants had not moved in last Saturday; after all, they DID move in last Saturday (Fischer Reference Fischer2017, 82, our emphasis).

As we have seen, Ockham responds to the arguments for theological determinism by distinguishing hard facts about the past—facts that are genuinely and strictly about the past—from soft facts about the past; only the former, he says, are necessary per accidens. This response is intuitively plausible (Plantinga Reference Plantinga1986, 251, our emphasis).

I claim that, once you believe that facts about 1492 depend on your choices, FP would no longer seem intuitive… Of course, such intuitions are not infallible and I have not established that FP is false. But I do think that reflection on such cases reveals that what may look like intuitive support for FP is really only support for [the fixity of the independent past]. Once we drop the assumption of independence, FP is not so intuitive (Swenson Reference Swenson2016, 664–665, our emphasis).

Given that Plantinga (Reference Plantinga1986) and Swenson (Reference Swenson2016) reach a very different conclusion (i.e. some form of compatibilism) from Fischer (Reference Fischer2017), it is evident that what is considered ‘intuitive’ or ‘plausible’ by partisans in this debate is not universally shared. But whose intuitions should be followed? If philosophical wisdom is divided, perhaps it would be helpful to probe what the majority of people without philosophical training find intuitive and plausible.

We do not presume, however, that getting clear on folk intuitions regarding these matters will neatly resolve the philosophical debate.Footnote 2 There are a number of ways folk intuitions may be handled by the different positions at play. One thing that folk intuitions might help us with, however, is determining where the initial burden of proof lies. Some philosophers take folk

intuitions (i.e. common sense) seriously and often make it a point to align their theories with such intuitions. Of course, a commitment to common sense can be overturned, but only through serious philosophical argumentation. Common sense, we might say, should be considered the default position and is presumed innocent until proven guilty.

There are at least two places in the debate that the study of folk intuitions may help in establishing the burden of proof. First, it would be helpful to find out whether compatibilism or incompatibilism is the default position at the outset of this debate. Philosophers do not agree. Pike suggests that compatibilism is intuitive:

[In] his Consolation of Philosophy, Boethius entertained (though he later rejected) the claim that if God is omniscient, no human action is voluntary. This claim seems intuitively false. Surely, given only a doctrine describing God’s knowledge, nothing about the voluntary status of human actions will follow (Pike Reference Pike1965, 27, our emphasis).Footnote 3

Plantinga, on the other hand, suggests that incompatibilism is intuitive:

But divine foreknowledge and human freedom, as every twelve-year-old Sunday School student knows, can seem to be incompatible; and at least since the fifth century AD philosophers and theologians have pondered the question whether these two doctrines really do conflict. (Plantinga Reference Plantinga1986, 235, our emphasis)

Second, a better understanding of folk intuition regarding a more fine-grained area of this debate regarding the fixity of the past may also benefit from establishing the burden of proof. Is the past fixed or only a part of the past fixed? Some philosophers, for example, have found Plantinga’s ant colony example to be compelling evidence for the possibility of the past depending on the future. Here, for example, is Thomas Flint:

After all, why think it’s dialectically kosher to assume from the start that (FP) is true? Plantinga’s story [about the ants] could be seen as a way of showing that it’s not… Fischer might respond to such a tu quoque by pointing again to the prephilosophical backing for (FP) … [but] to suggest that the vague intuition most of us have regarding the fixity of the past obviously commits us to anything quite so controversial as (FP) is surely not plausible (Flint Reference Flint2017, 20, our emphasis).

Similarly Swenson argues, ‘once you believe that facts about [the past] depend on your choices, [FP] would no longer seem intuitive’ (Reference Swenson2016, 57).

Others, like Fischer and Tognazzini, demur. They write:

But how exactly does the dependence point in any way vitiate – or even address – the point about the fixity of the past? … If fixity stems from over-and-done-with-ness, and over-and-done-with-ness is a function of temporal intrinsicality, both of which seem plausible, then it would seem more reasonable to conclude that even the dependent hard facts are fixed (Fischer and Tognazzini Reference Fischer, Tognazzini and Fischer2016, 231, our emphasis).

Philosophers like Fischer and Tognazzini reject the dependence theory. They do so because FP is ‘highly intuitive’ and ‘seems more reasonable’ than countenancing dependent hard facts that are not fixed.

With all the references to what is ‘intuitive’ and ‘plausible’ on both sides of this debate, whether the various claims philosophers make are consistent with common sense is ripe for empirical investigation. In what follows we will outline a study we ran to better understand (1) whether the folk have compatibilist or incompatibilist intuitions regarding the relationship between omniscience and free will and (2) what parts of the past the folk think are fixed.

Study 1

We initially test our hypotheses in the United States using three separate situations: one that has been commonly used in past experimental research (Newcomb’s Paradox) and two novel situations (ant colony, prayer).Footnote 4

Participants

We sampled participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) using the Cloud Research Platform, which is an online platform that allows researchers to compensate participants with a monetary fee for completing the study. We only sampled Cloud Research approved participants (Litman et al. Reference Litman, Robinson and Abberbock2017).

We estimated a need for 75 participants for a one-sample t-test using G*Power (Version 3.1) with the following parameters: Power = .95, alpha = .05, d = .50. We doubled this sample size to N = 150 to account for people failing the surface level comprehension checks of the vignettes and to allow us to examine any relationships between free will and religiosity in an exploratory fashion.

A total of 160 people ended up clicking on the survey. Six of them did not finish the survey, resulting in 154 participants (M Age = 39.42, SD Age = 10.42, 56.3% male, 78.1% White).Footnote 5

Procedure and materials

Participants clicked on a Qualtrics-hosted study that was advertised as ‘Comprehending Abstract Concepts’ on Amazon MTurk. After completing a consent form, participants were given three vignettes in counterbalanced order: Newcomb, Ant, and Prayer. Here is the Newcomb vignette:

Regardless of what you think about God, let’s imagine a universe where God exists and God knows everything, including what will happen in the future. Moreover, God’s knowledge is perfect - He is never wrong about what He knows.

In this universe, Paul is presented with two boxes, A and B. A is transparent and contains $1,000. B is opaque and either contains $1,000,000 or nothing. Paul now has a choice between two actions:

1. Take what is in both A and B.

2. Take only what is in B.

Paul knows that there is $1,000 in A because A is transparent and he can see the money. Paul does not know whether there is $1,000,000 or nothing in B. However, Paul does know the following two things about what is in B:

If God knows that Paul will take what is in both A and B, God puts nothing in B. If God knows that Paul will take only what is in B, God puts $1,000,000 in B.

100 years ago because of the choice Paul is about to make and God’s perfect knowledge of it, God already knew Paul will take only what is in B. So God put $1,000,000 in B. If God had known instead that Paul will take what is in both A and B, then God would have put nothing in B. As it is, there has been $1,000,000 in B for the past 100 years.

Though God already knows what Paul will do, Paul has not actually made a decision yet. He is going to make a decision now.

Here is the Ant vignette:

Regardless of what you think about God, let’s imagine a universe where God exists and God knows everything, including what will happen in the future. Moreover, God’s knowledge is perfect – He is never wrong about what He knows.

In this universe a colony of carpenter ants moved into Bill’s yard last Saturday. Since this colony hasn’t yet had a chance to get properly established, its new home is still a bit fragile. In particular, if Bill were to mow his lawn this afternoon, the colony would be destroyed. Although nothing remarkable about these ants is visible to the naked eye, God, for reasons of his own, intends that the ant colony be preserved.

Because of the choice Bill is going to make and God’s perfect knowledge of it, God already knew Bill will not mow his lawn. If God had known instead that Bill will mow his lawn, then God would have prevented the ants from moving in. As it is, the ants have been in Bill’s yard since last Saturday.

Though God already knows what Bill will do, Bill has not actually made a decision yet. He is going to make a decision now.

Here is the Prayer vignette:

Regardless of what you think about God, let’s imagine a universe where God exists and God knows everything, including what will happen in the future. Moreover, God’s knowledge is perfect – He is never wrong about what He knows.

In this universe David had been suffering from serious heart problems. Last night he was rushed to the hospital because of a sudden heart attack. Despite the doctors’ best efforts David died at 11 pm.

A few hours later David’s son, Chris, for some reason wakes up at 3 am. Chris does not yet know that his father has already died. His father’s heart problems had been on his mind so he is now debating whether he should pray to God or not.

Because of the choice Chris is going to make and God’s perfect knowledge of it, God already knew Chris will not pray. If God had known instead that Chris will pray, then God would have prevented David from dying of the sudden heart attack. As it is, David has been dead for the past four hours.

Though God already knows what Chris will do, Chris has not actually made a decision yet. He is going to make a decision now.

Each of these vignettes was chosen for a reason. The Newcomb vignette is based on Newcomb’s Paradox and has been widely discussed within philosophy both inside (Craig Reference Craig1987) and outside philosophy of religion (Nozick Reference Nozick and Rescher1969; Wolpert and Benford Reference Wolpert and Benford2013). The Ant vignette is based on Plantinga’s ant colony scenario and it has been widely discussed within philosophy of religion (Cyr and Law Reference Cyr and Law2020; Leftow Reference Leftow1991a, Reference Leftow1991b).

The Prayer vignette was developed because we felt it was more ecologically sound than the other two. The Newcomb vignette is situated in contrived circumstances that do not arise in our actual lives. The Ant vignette, though situated in everyday circumstances, focuses on a rather inconsequential event. The Prayer vignette, on the other hand, is well situated and focuses on consequential matters.Footnote 6

After each vignette participants were given five statements to check for comprehension using binary choice (True or False). Here are the statements for the Prayer vignette:

1. David died last night at 11 pm.

2. Chris woke up a few hours later at 3 am the next morning.

3. In this universe, God is sometimes wrong about what He knows.

4. God already knew that Chris will not pray.

5. Chris has not made a decision about whether to pray yet.

Then participants were given two statements about the main character’s free will and ability to do otherwise to examine whether participants are compatibilist or incompatibilist about the relationship between omniscience and free will using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). Here are the statements for the Prayer vignette:

1. Chris will freely choose not to pray for David’s heart problems.

2. Though Chris will not pray for David’s heart problems, Chris has the ability to pray for David’s heart problems.

If participants agree (i.e. somewhat agree, agree, or strongly agree) with the statement concerning the ability to do otherwise then they were given two additional statements. These statements were designed to see if participants would accept that various facts about the past would be different than they in fact are given that the main character (e.g. Chris) does otherwise. One statement is about an uncontroversial hard fact about the past and the other is about God’s past belief.

1. If Chris, instead of deciding not to pray, decides to pray for David’s heart problems, then David would not have died at 11 pm last night.

2. If Chris, instead of deciding not to pray, decides to pray for David’s heart problems, then God would have known that Chris will pray.

After reading through and responding to questions for all three vignettes, participants reported their beliefs about free will and religiosity in a counterbalanced fashion. To assess participants’ belief in free will, we had them complete the Free Will Inventory (FWI; Nadelhoffer et al. Reference Nadelhoffer, Shepard, Nahmias, Sripada and Ross2014). The first part of the FWI contains three subscales that assess people’s belief in free will (‘People ultimately have control over their decisions and their actions’), determinism (‘People’s choices and actions must happen precisely the way they do because of the laws of nature and the way things were in the distant past’), and dualism (‘Each person has a non-physical essence that makes that person unique’). Each of these subscales had five-items. The second part of the FWI assesses people’s belief about the nature of free will (‘People have free will as long as they are able to do what they want without being coerced or constrained by other people’) and the nature of morality (‘People deserved to be blamed and punished for bad actions only if they acted in their own free will’), each with seven items. The FWI items were on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

We assess people’s religiosity using the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (Cappelen Reference Cappelen2012). We used the 20-item CRS that allows for an assessment of religiosity across non-Christian religions. The CRS assesses multiple components of religiosity, including people’s behaviour, beliefs, and religious importance. For items used in the scales see appendices E and F in our materials document on our OSF page.

Participants lastly reported their demographics before being debriefed and compensated.

Results

To test the hypotheses, a series of one-sample t-tests were conducted to examine whether participants’ scores for given items were above the midpoint of 3.5. We report the Hedge’s g effect size with each t-test, along with means and standard deviations, below.

Prayer vignette

A total of 127 out of 154 (82.5%) of the sample correctly responded to all comprehension items about the Prayer vignette. Participants perceived that Chris will freely choose not to pray for David’s heart problems (M = 4.64, SD = 1.34) significantly above the midpoint, t (126) = 9.56, p < .001, g = .85. Participants also perceived that Chris has the ability to do otherwise and pray for David’s heart problems even though he will not (M = 4.97, SD = 1.15) significantly above the midpoint, t (126) = 14.34, p < .001, g = 1.27. Participants had more agreement that Chris has the ability to do otherwise than that Chris will freely choose not to pray (t (94) = − 3.75, p < .001, g = − .38).

The majority of participants (88%) who got all the comprehension questions right agreed that Chris has the ability to pray for David’s heart problems even though he will not. Regarding the fixity of the past, these participants believed that were Chris to pray for David’s heart problems, David would not have had a heart attack the night before significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.71, SD = 1.42), t (111) = 9.07, p < .001, g = .86. Moreover, these participants believed that were Chris to pray for David’s heart problems, God would have known that Chris will pray for David’s heart problems significantly above the midpoint (M = 5.35, SD = 0.97), t (111) = 20.26, p < .001, g = 1.90. Participants had more agreement that what God would have known would have been different than David’s not having a heart attack (t (111) = − 5.08 p < .001, d = − .48) were Chris to pray.

Newcomb vignette

A total of 105 out of 154 (68.2%) of the sample correctly responded to all comprehension items about the Newcomb Vignette. Participants perceived that Paul will freely choose to take what is in B (M = 4.58, SD = 1.28) significantly above the midpoint of 3.5, t (104) = 8.62, p < .001, g = .84. Participants also perceived that Paul has the ability to do otherwise and take what is in both A and B (M = 4.82, SD = 1.26) significantly above the midpoint of 3.5, t (104) = 10.71, p < .001, g = 1.04. Participants had more agreement that Paul has the ability to do otherwise than that Paul will freely choose to take what is in B (t (94) = − 2.20, p = .030, g = − .22).

The majority of participants (84%) who got all the comprehension questions right agreed that Paul has the ability to take what is in both A and B. Regarding the fixity of the past, these participants believed that were Paul to take what is in both A and B then nothing would have been in B significantly above the midpoint of 3.5 (M = 5.05, SD = 1.34), t (88) = 10.83, p < .001, g = 1.16. Moreover, they believed that were Paul to take what is in both A and B then God would have known that Paul will take what is in both A and B significantly above the midpoint of 3.5 (M = 5.38, SD = 1.04), t (88) = 16.87, p < .001, g = 1.78. Participants had more agreement that what God would have known would have been different than the million dollars not being in B (t (87) = − 2.31, p = .023, d = − .24) were Paul to take what is in both A and B.

Ant vignette

A total of 119 out of 154 (77.3%) of the sample correctly responded to all comprehension items about the Ant vignette. Participants perceived that Bill will freely choose not to mow his lawn (M = 4.50, SD = 1.45) significantly above the midpoint, t (118) = 7.53, p < .001, g = .69. Participants also perceived that Bill has the ability to do otherwise and mow his lawn even though he will not (M = 4.93, SD = 1.26) significantly above the midpoint, t (118) = 12.40, p < .001, g = 1.13. Participants had more agreement that Bill has the ability to do otherwise than that Bill will freely choose not to mow his lawn (t (94) = − 4.20, p < .001, g = − .43).

The majority of participants (87%) who got all the comprehension questions right agreed that Bill has the ability to mow his lawn even though he will not. Regarding the fixity of the past, these participants believed that were Bill to mow his lawn then the ants would never have moved in significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.91, SD = 1.39), t (104) = 10.34, p < .001, g = 1.00. Moreover, they believed that were Bill to mow his lawn then God would have known that Bill will mow his lawn significantly above the midpoint (M = 5.46, SD = 0.89), t (104) = 22.44, p < .001, g = 2.18. Participants had more agreement that what God would have known would have been different than the ants not moving in (t (103) = − 4.08, p < .001, d = − .40) were Bill to mow his lawn.

Exploratory analysis

Across all three conditions higher religiosity scores and higher determinism scores correlated with lower comprehension. Unsurprisingly, higher free will scores correlated with higher compatibilism scores.

Discussion

The results of this study strongly suggest that folk intuition is compatibilist and coincides with Pike’s claim (and contradicts Plantinga’s claim) that the statement ‘if God is omniscient, no human action is voluntary’ seems ‘intuitively false’. Across all three vignettes participants tended to agree with the claim that the main characters in their respective scenarios will freely act and have the ability to do otherwise despite God’s knowing in advance what they will do.

We can also see from these results that participant belief in the main characters’ acting freely is tightly correlated with participant belief in the main characters’ ability to do otherwise. While this doesn’t show that participants take the ability to do otherwise to be a necessary condition for acting freely, it does show that participants, in finding omniscience to be compatible with free will, do not feel the need to tease free will apart from the ability to do otherwise in order to make sense of compatibilism. This is interesting because it suggests that compatibilist responses to Pike’s argument (e.g. Hunt Reference Hunt and McCann2017) that try to show that the ability to do otherwise is not necessary for free will are not the first to come to people’s minds. Indeed, participants across all three conditions had more agreement that the main character has the ability to do otherwise than that the main character will act freely.

The results of this study also suggest that folk intuition coincides with dependence theorists. Not only did participants tend to agree that the main characters have the ability to do otherwise, but if the main characters were to do otherwise then certain past events (e.g. David’s passing away of a heart attack and God’s belief that Chris will not pray) would never have happened. That is, in line with dependence theorists, participants generally believe that the past would have been different and FP would, at least for certain facts (both hard and soft), have been relinquished.

That being said, there is a statistically significant difference in the way participants responded to the malleability of God’s past beliefs and hard facts about the past. Though God’s beliefs and the relevant hard facts are both parts of the past, participants find it more natural to see God’s belief as being malleable. This suggests participants do make a distinction critical to Ockhamism – the distinction between an ‘uncontroversial’ hard fact and God’s past beliefs.

While intriguing, this at most shows that Western Christians on average make the Ockhamist’s distinction. To improve understanding of the scope of the Ockhamist distinction along with intuitions that coincide with dependence theorists, we need to sample from a non-Western culture.

Study 2

As a follow-up study, we decided to run Study 1 in a different religious and cultural context. Specifically, we focused on Hindus living in India in Study 2.

Participants

Similar to Study 1, we sampled participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) using the Cloud Research Platform. We focus on MTurkers living in India who had 95% completion rate and had completed at least 100 HITs, per recommendations for obtaining high-quality data on MTurk.

We estimated a need for 75 participants for a one-sample t-test, similar to Study 1. We doubled this sample size to N = 150 to account for people failing the surface level comprehension checks of the vignettes and to allow us to examine any relationships between free will and religiosity in an exploratory fashion.

A total of 174 people clicked on the survey. Thirteen of them did not pass the initial language comprehension check, while an additional 21 people were removed for failing two additional attention checks. Removing these individuals resulted in 141 participants (M Age = 31.20, SD Age = 4.86, 65.9% male).

Procedure and materials

Similar to Study 1, participants clicked on a Qualtrics-hosted study that was advertised as ‘Comprehending Abstract Concepts’ on Amazon MTurk. After completing a consent form, participants were given the Newcomb’s Paradox, Ant Colony, and Prayer vignettes in counterbalanced order. The vignettes and associated items for Newcomb’s Paradox and the Prayer vignette were the same as Study 1, but the names were adjusted for Indian culture. For the Ant Colony vignette, in addition to changing the names, we adjusted the behaviour from mowing the lawn to sweeping the porch. For the exact wording see Appendix D in our materials document on our OSF page.

The Free Will Inventory and Centrality of Religiosity scales were the same as Study 1. Participants completed these scales in a counterbalanced order after reading through all three vignettes. Participants lastly reported their demographics before being debriefed and compensated for their time.

Results

To test the hypotheses, a series of one-sample t-tests were conducted to examine whether participants’ scores for given items were above the midpoint of 3.5. We report the Hedge’s g effect size with each t-test, along with means and standard deviations, below.

Prayer vignette

A total of 103 out of 141 (73.0%) of the sample correctly responded to all comprehension items about the Prayer vignette. Participants perceived that Kamal will freely choose not to pray for Deepak’s heart problems (M = 4.63, SD = 1.08) significantly above the midpoint, t (103) = 10.67, p < .001, g = 1.04. Participants also perceived that Kamal has the ability to do otherwise and pray for Deepak’s heart problems even though he will not (M = 4.90, SD = 1.00) significantly above the midpoint, t (103) = 14.31, p < .001, g = 1.40. Participants had similar levels of agreement regarding Kamal’s freely choosing to pray and his ability to do otherwise (t (140) = − 1.41, p = .161, g = − .12).

The majority of participants (94.2%) who got all the comprehension questions right agreed that Kamal has the ability to pray for Deepak’s heart problems even though he will not. Regarding the fixity of the past, these participants believed that were Kamal to pray for Deepak’s heart problems, Deepak would not have had a heart attack the night before significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.56, SD = 1.27), t (96) = 8.22, p < .001, g = .83. Moreover, these participants believed that were Kamal to pray for Deepak’s heart problems, God would have known that Kamal will pray for Deepak’s heart problems significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.77, SD = 1.34), t (96) = 9.40, p < .001, g = 0.95. Participants had similar levels of agreement with the claims that what God would have known would have been different and that Deepak would not have had a heart attack (t (96) = − 1.55, p = .125, d = − .16) were Kamal to pray.

Newcomb vignette

A total of 88 out of 141 (62.4%) of the sample correctly responded to all comprehension items about the Newcomb Vignette.Footnote 7 Participants perceived that Aditya will freely choose to take what is in B (M = 4.89, SD = 0.67) significantly above the midpoint, t (87) = 19.46, p < .001, g = 2.07. Participants also perceived that Aditya had the ability to do otherwise and take what is in both A and B (M = 4.93, SD = 1.26) significantly above the midpoint, t (87) = 15.02, p < .001, g = 1.60. Participants had similar levels of agreement regarding Aditya’s freely choosing to take what is in B and his ability to do otherwise (t (140) = − 0.43, p = .680, g = − .04).

The majority of participants (95.5%) who got all the comprehension questions right agreed that Aditya had the ability to take what is in both A and B. Regarding the fixity of the past, these participants believed that were Aditya to take what is in both A and B then nothing would have been in B significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.68, SD = 1.15), t (83) = 9.37, p < .001, g = 1.01. Moreover, they believed that were Aditya to take what is in both A and B then God would have known that Aditya will take what is in both A and B significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.93, SD = 1.11), t (83) = 11.84, p < .001, g = 1.28. Participants had similar levels of agreement with the claims that what God would have known would have been different and that nothing would be in B (t (83) = − 1.74, p = .085, d = − .19) were Aditya to take both A and B.

Ant vignette

A total of 104 out of 141 (73.8%) of the sample correctly responded to all comprehension items about the Ant vignette. Participants perceived that Amit will freely choose not to sweep his house (M = 4.84, SD = 0.81) significantly above the midpoint, t (103) = 16.75, p < .001, g = 1.64. Participants also perceived that Amit has the ability to do otherwise and sweep his house even though he will not (M = 4.89, SD = 0.92) significantly above the midpoint, t (103) = 15.40, p < .001, g = 1.50. Participants had similar levels of agreement regarding Amit’s freely choosing not to sweep his house and his ability to do otherwise (t (140) = − 0.08, p = .939, g = − .01).

The majority of participants (97.1%) who got all the comprehension questions right agreed that Amit has the ability to sweep his house even though he will not. Regarding the fixity of the past, these participants believed that were Amit to sweep his house then the ants would never have moved in significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.58, SD = 1.22), t (100) = 8.94, p < .001, g = 0.88. Moreover, they believed that were Amit to sweep his house then God would have known that Amit will sweep his house significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.74, SD = 1.39), t (100) = 8.98, p < .001, g = 0.89. Participants had similar levels of agreement with the claims that what God would have known would have been different and that the ants would never have moved in (t (100) = − 1.34, p = .184, d = − .13) were Amit to sweep his house.

Exploratory analysis

In contrast to US participants in Study 1, Indian participants in Study 2 did not exhibit any interesting correlations between religiosity and comprehension. Where higher religiosity scores in the US correlated with lower comprehension, religiosity scores had no correlations with comprehension in India. There were no other correlations that held across all three conditions.

Discussion

We can see that the participants in Study 2 responded in a similar way to the participants in Study 1. It suggests that compatibilism and dependence theory are natural ways of understanding the relationship between omniscience and free will. Moreover, these tendencies are robust across a different religious and cultural context. While interesting, the sample used in Study 2 does not allow us to draw conclusions about the relationship between Christianity and beliefs about the relationship between omniscience and free will. For this we need a study that varies culture but holds constant religion. Furthermore, to better understand potential interactions between culture and Ockhamist intuitions, it would be prudent to sample both Christians and non-Christians from a non-Western culture.

Study 3

As a final study we decided to run Study 1 in a different cultural context while attempting to keep the religious context fixed. Specifically, we focused on Christian and non-religious South Koreans.

Participants

We sampled participants from South Korea using Qualtrics Panels, which is a subdivision of Qualtrics that samples participants of a particular demographic. We estimated a need for N = 75 participants, which we doubled to N = 150 to account for people failing the surface-level comprehension checks of the vignettes. We further doubled this sample size to N = 300 to examine both Christians and non-religious individuals. A total of 338 people ended up completing the survey. All participants passed the single attention check and were retained in the further analysis (M Age = 37.50, SD Age = 11.74, 60.9% male, 98.5% Korean).

Procedure and materials

Participants were contacted from Qualtrics. People who were interested in this survey were directed to a consent form before being given the Newcomb’s Paradox, Ant Colony, and Prayer vignette in counterbalanced order. The vignettes and associated items for Newcomb’s Paradox and the Prayer vignette were the same as the previous studies, but the names were adjusted for South Korean culture. For the Ant Colony vignette, we adjusted the behaviour back from sweeping the porch to mowing the lawn. The Free Will Inventory and Centrality of Religiosity scales were the same from previous studies and were completed in a counterbalanced order after reading through all three vignettes. Participants lastly reported their demographics before being debriefed and compensated for their time. All parts of the survey, vignettes, questions, scales, and demographics, were translated into Korean.

Results

Similar to the previous studies, a series of one-sample t-tests were conducted to examine whether participant scores for the given items were above the midpoint of 3.5. We report the Hedge’s g effect size with each t-test, along with means and standard deviations, below.

Prayer vignette

A total of 231 out of 338 (68.3%) of the sample correctly responded to all comprehension items about the Prayer vignette. Participants perceived that Seunghyeon will freely chose not to pray for Byeongguk’s heart problems (M = 4.33, SD = 1.04) significantly above the midpoint, t (230) = 9.36, p < .001, g = 0.61. Participants also perceived that Seunghyeon has the ability to pray for Byeongguk’s heart problems even though he will not (M = 4.92, SD = 1.25) significantly above the midpoint, t (230) = 17.24, p < .001, g = 1.13. Participants had more agreement that Seunghyon has the ability to do otherwise than that Seunghyon will freely choose to not to pray (t (337) = − 6.12, p < .001, g = − .33).

The majority of participants (90.0%) who got all the comprehension questions right agreed that Seunghyeon has the ability to pray for Byeongguk’s heart problems even though he will not.

These participants believed that were Seunghyeon to pray for Byeongguk’s heart problems, Byeongguk would not have had a heart attack the night before significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.21, SD = 1.59), t (208) = 6.45, p < .001, g = .45. Moreover, these participants believed that were Seunghyeon to pray for Byeongguk’s heart problems, God would have known that Seunghyeon will pray for Byeongguk’s heart problems significantly above the midpoint (M = 3.90, SD = 1.73), t (208) = 3.36, p < .001, g = 0.23. Participants had less agreement that what God would have known would have been different than Byeongguk’s not having a heart attack (t (207) = 2.17, p = .031, d = − .15) were Seunghyeon to pray.

Newcomb vignette

A total of 170 out of 338 (50.3%) of the sample correctly responded to all comprehension items about the Newcomb Vignette.Footnote 8 Participants perceived that Minsu will freely choose to take what is in B (M = 4.39, SD = 1.40) significantly above the midpoint, t (169) = 8.31, p < .001, g = 0.64. Participants also perceived that Minsu had the ability to take what is in both A and B (M = 4.72, SD = 1.41) significantly above the midpoint, t (169) = 11.29, p < .001, g = 0.86. Participants have more agreement that Minsu had the ability to do otherwise than that Minsu will freely choose to take what is in B (t (337) = − 4.49, p < .001, g = − .24).

The majority of participants (84.1%) who got all the comprehension questions right agreed that Minsu had the ability to take what is in both A and B. These participants believed that were Minsu to take what is in both A and B then nothing would have been in B significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.71, SD = 1.51), t (142) = 9.56, p < .001, g = 0.80. Moreover, they believed that were Minsu to take what is in both A and B then God would have known that Minsu will take what is in both A and B significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.35, SD = 1.76), t (142) = 5.78, p < .001, g = 0.48. Participants had less agreement that what God would have known would have been different than the million dollars not being in B (t (142) = 2.04, p = .044, d = .17) were Minsu to take what is in both A and B.

Ant vignette

A total of 219 out of 338 (64.8%) of the sample correctly responded to all comprehension items about the Ant vignette. Participants perceived that Youngchul will freely choose not to mow his lawn (M = 4.43, SD = 1.40) significantly above the midpoint, t (218) = 9.85, p < .001, g = 0.66. Participants also perceived that Youngchul has the ability to mow his lawn even though he will not (M = 4.98, SD = 1.27) significantly above the midpoint, t (218) = 17.23, p < .001, g = 1.16. Participants had more agreement that Youngchul has the ability to do otherwise than that Youngchul will freely choose not to mow his lawn (t (337) = − 5.46, p < .001, g = − .30).

The majority of participants (90.4%) who got all the comprehension questions right agreed that Youngchul has the ability to mow his lawn even though he will not. These participants believed that were Youngchul to mow his lawn then the ants would never have moved in significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.61, SD = 1.46), t (198) = 10.75, p < .001, g = 0.76. Moreover, they believed that were Youngchul to mow his lawn then God would have known that Youngchul will sweep his house significantly above the midpoint (M = 4.27, SD = 1.71), t (198) = 6.30, p < .001, g = 0.47. Participants had less agreement that what God would have known would have been different than the ants not moving in (t (197) = 2.45, p = .015, d = .17) were Youngchul to mow his lawn.

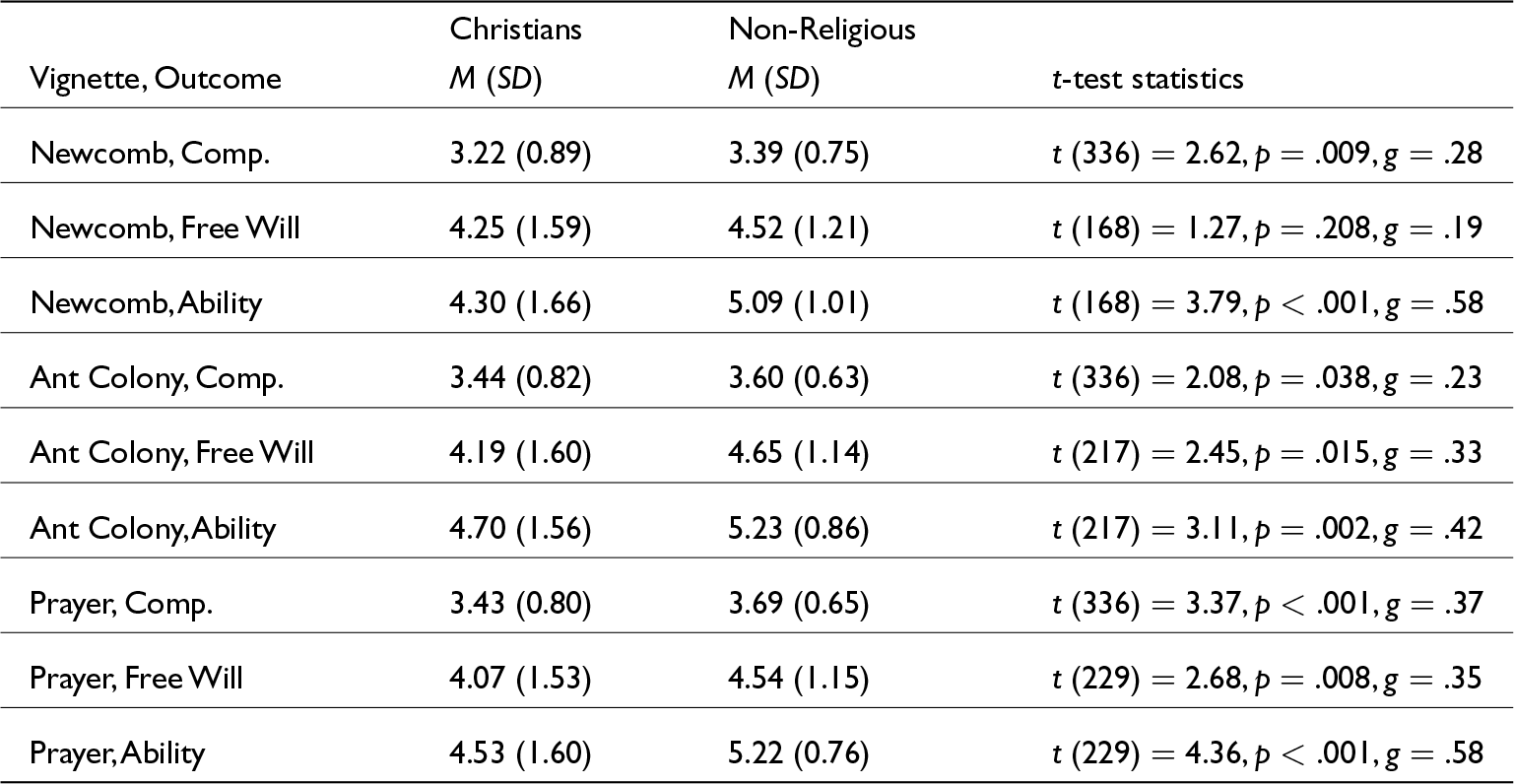

Exploratory analysis

A series of independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine whether Christians and non-religious individuals differed in their surface-level comprehension and their scores on the compatibilist items. First, across all conditions, non-religious individuals had better surface-level comprehension than Christians. Second, after removing people who failed the vignettes’ respective comprehension checks, results showed that non-religious individuals had more compatibilist views of omniscience and free will and omniscience and the ability to do otherwise than Christians across the Ant Colony and Prayer vignettes. For Newcomb’s Paradox, non-religious individuals had higher compatibilism scores for the ability to do otherwise but not for free will. These findings suggest that non-religious individuals in South Korea better comprehend deterministic scenarios and have more compatibilist views of omniscience and free will.

General discussion

Our experimental results strongly suggest that folk intuitions about the relationship between divine omniscience and human free will are compatibilist and, in particular, support the dependence theory across three different cultural and religious contexts. This suggests that there is a presumption of compatibilism when entering debates over the relationship between divine omniscience and free will.

US and South Korean participants agreed more that the main character in each vignette has the ability to do otherwise than that the main characters freely choose to do what they are foreknown to do. There was no statistical difference, however, between the levels of agreement expressed by Indian participants. It is difficult to infer anything (from our data) about the differing levels of agreement between the main characters’ freely choosing to do what they are foreknown to do and their having the ability to do otherwise.

US participants agreed more with God’s past beliefs being different than with hard facts being different. There was no statistical difference in the level of agreement over these two categories of past events among Indian participants. Interestingly, South Korean participants agreed less with God’s past beliefs being different than hard facts being different. As a result, it is impossible to infer anything (from our data) about the differing levels of agreement between God’s past beliefs being different and hard facts being different across cultures.

Through our exploratory analyses we found that lower vignette comprehension was correlated with higher religiosity scores in the US and in South Korea. In South Korea explicitly Christian or non-religious participants were recruited. In the US the dominant religious affiliation was Christian. In contrast there was no correlation found between vignette comprehension and religiosity scores (or any scores on the two scales) in India. This suggests that Christian commitments appear to play a role in comprehending the three vignettes in our studies (and perhaps, more generally, any vignette involving the interaction of omniscience and human actions), and points the way to valuable future experimental research.

Our work has a number of limitations. One might have a worry that participants are not necessarily reporting what is intuitive but what they have come to believe based on prior commitments.Footnote 9 For example, a Christian, given prior theological commitments to both divine omniscience and human free will, may judge that the claims are compatible with each other despite finding the compatibility to be unintuitive. While this presents a potential confound for our instrument, this may not be an issue given the results of Study 3. There we found, somewhat surprisingly, that non-religious individuals had higher compatibilism scores than Christians. Presumably non-religious individuals have no prior commitments that would push them to affirm the compatibility of divine omniscience and human free will.

Another worry is that the Newcomb and Prayer vignettes might suffer from a kind of Knobe (Reference Knobe2003).Footnote 10 Perhaps participant conceptualization of the nature of action (whether it is free or not) depends in some way on the good or bad consequences involved. In the Newcomb vignette Paul will take what is in box B (presumably because he believes there will be $1,000,000). But what if the vignette presented Paul’s choosing both boxes A and B instead (and the prospect of a guaranteed mere $1,000)? Would the different amounts of money at stake affect how participants understand Paul’s action as being free or not? In the Prayer vignette David dies and Chris will not pray. But what if the vignette presented David living and Chris’ choosing to pray? Will David’s living (vs. dying) and Chris’ praying (vs. not praying) affect how participants understand Chris’ action as being free or not? This is a genuine worry that can only be answered through empirical investigation and offers a way forward in extending the present studies. We are, however, skeptical that something like a Knobe Effect will be revealed. This is because the Ant vignette does not seem to have any serious good or bad consequences at stake. Whether or not Bill mows the lawns seems inconsequential and either way the ant colony will be preserved.

Recent work (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Dykhuis, Nadelhoffer, Lombrozo, Knobe and Nichols2024; Nadelhoffer et al. Reference Nadelhoffer, Murray and Murray2023, Reference Nadelhoffer, Rose, Buckwalter and Nichols2020) in the experimental philosophy of free will critiques the use of vignettes to study folk intuitions regarding the relationship between determinism (not omniscience) and free will. It is argued the vignettes (that describe deterministic scenarios) are not properly understood by participants. Participants tend to make comprehension errors (e.g. conflating determinism with fatalism) that jeopardize the validity of the results. This critique, while an important check on existing practices, may not be a serious issue with our studies. First, the comprehension issues in these studies may stem from features unique to determinism (e.g. any change in the present entails a change in the entire past history of the world) that may be difficult to convey through writing alone. Omniscience does not seem to suffer from such features. Second, we were careful to include a variety of comprehension checks that ensure that participants take on board details (e.g. God already knows what the main character will do before the main character acts) critical for the comprehension of omniscience. Though we believe our studies do not suffer from excessive participant comprehension errors, it is important to be wary of this concern and actively consider ways that existing vignette-based instruments might be improved. Perhaps there are ways to develop instruments that do not depend solely on vignettes for future studies on the relationship between free will and omniscience.Footnote 11

A final worry is that establishing common sense compatibilism adds nothing to the philosophical debate. Fischer, for example, writes:

The theological incompatibilist should concede from the outset that the ‘plausible’ or ‘reasonable’ (from the viewpoint of common sense) view would be that (say) Jones has it in his power at T 2 to do otherwise, and Paul has it in his power this afternoon to mow his lawn. After all, theological incompatibilism challenges the common-sense view that we are often free to do otherwise. So, if the example of Paul and the Ant Colony is simply meant to show that compatibilism is coherent (logically possible) and reflects common sense, I don’t see how it does much philosophical work (Fischer Reference Fischer2017, 71–72).

Evidently Fischer is willing to grant a presumption of compatibilism. He nevertheless thinks that such a presumption plays no philosophical role. First, we should note that the question of whether or not compatibilism reflects common sense is an empirical question. It is not something we can simply determine by fiat. Evidence is needed to determine the answer to this question and we have marshaled preliminary evidence here. Second, whether or not compatibilism’s being part of common sense matters philosophically is itself a philosophical matter. Common sense has played a remarkable role in closely related philosophical domains. In debates over the compatibility of free will and determinism (Nahmias et al. Reference Nahmias, Morris, Nadelhoffer and Turner2005), for example, it was widely taken for granted that incompatibilism reflects common sense and therefore the burden of proof lies with compatibilism. This critically shaped the historical landscape of the debate because the incompatibilist essentially occupied the default position.

For future work it would be interesting to integrate the present studies with experimental work being done regarding folk intuitions of the relationship between free will and determinism.Footnote 12 Our results show a robust correlation between free will and the ability to do otherwise within the context of omniscience but this is not necessarily the case when it comes to the context of determinism. Moreover, we haven’t probed the relationship between divine omniscience and moral responsibility.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.