Introduction

Think about an animal in the evolutionary history of humans that, like Rowe's fawn, died in a forest fire. But imagine that this animal didn't just meet a bad end. Imagine its lot was far worse. Its whole earthly life was filled with undeserved suffering and was overall bad. Would God allow something so terrible?

I think God would. I claim that it is permissible for God to allow a creature to suffer horrendously if five conditions obtain:

i. God gives the creature an infinitely good post-Resurrection existence.

ii. God makes a lot of creatures with infinitely good lives that could not have been made if that creature had not been allowed to suffer horrendously.

iii. God allows horrendous suffering at least in part so that such creatures may exist.

iv. If God had not allowed any horrendous suffering, then that creature could not have existed.

v. God has no special obligation (such as one due to promising) to prevent the relevant instance of horrendous suffering.

I think that God satisfies all five conditions in almost all cases of horrendous evil. And so I think theism is able to plausibly explain almost all instances of horrendous suffering.

The metaphysics of origins

I am assuming origin essentialism. On this view, if something's origin were too different, it would not have existed. The theodicy does not fit with all versions of origin essentialism. On one gloss of the view, I could not have originated at a time or from materials that are too different. Consider:

Waiting: The fundamental particles that make up the sperm and egg combination that went on to form my actual zygote exist at the origin of the universe. Instead of getting those fundamental particles into sperm and egg form in the way He actually did, God leaves all of the particles just sitting there for billions of years until 1979 when He forms a duplicate of all of the world, including my particular sperm and egg combination, from the exact same materials that they are actually formed in 1979.

And:

Painless Evolution: Just like my actual evolutionary history with the exception that God miraculously intervenes so that no one in my evolutionary history ever feels pain. He also miraculously intervenes so that they behave just as the animals in my actual evolutionary history did even though they never feel pain and have no memories of pain.

Given the gloss in question, God creates me, and not a mere duplicate, in these cases. The material and time are the same as they actually are even if other things are different. So God can make me without allowing any horrendous evil. I accept an alternative formulation of origin essentialism discussed in Robertson (Reference Robertson1998), Hawthorne and Gendler (Reference Hawthorne and Gendler2000), Salmon (Reference Salmon1986), Forbes (Reference Forbes1986) and by Alexander Pruss.Footnote 1 The relevant formulation is this:

Assembly Origin Essentialism: If the materials from which a creature originated were assembled by a process that was too different, then that creature would not have existed.

On this view, introducing a big miracle, as in Waiting, or introducing many smaller miracles across billions of years, as in Painless Evolution, makes the process too different for the creature God gets to be me. I offer two arguments for adopting a strong enough version of origin essentialism to rule out my existence in Waiting and Painless Evolution.

First, accepting such a strong variant of origin essentialism yields a gain in explanatory power. Take a debate between realism and nominalism about a given domain. If adopting a view enables the realist about a domain to explain something puzzling about their view, then that is a reason for the realist to accept it. Similarly, adopting a version of origin essentialism like the one I discuss here allows the theist to explain why God allows evil. And that is a reason for the theist to accept it.

Second, adopting such a strong version of origin essentialism eliminates vagueness. A mereological nihilist or universalist might hold that there is no principled line to draw between when a collection of objects forms a new object other than never or always. So one should say that it is never or always. Something similar is true of the literature on events. Allowing that an event could have been different in any way at all leads to problems about how to say when the variation is too much for the event to be the same. So one standard view is that there can be no variation in events. What works for the metaphysics of mereology and events should work for the metaphysics of origins. There seems to be no principled way to say when an origin becomes so different that it fails to preserve the existence of an organism other than never or always. And it isn't plausible to hold that a change in origin never yields a different organism. So we should say that any change at all in the process by which the materials of my origin were assembled yields a mere duplicate of me rather than me.

The non-identity problem

Anyone who enjoys ethics or is a fan of Parfit's Reasons and Persons will recognize similarities between this theodicy and the cases that give rise to the non-identity problem. A natural thought is that since the agents in such examples act wrongly, God acts wrongly too. In light of this, it will be useful to consider the standard non-identity cases, the range of potential wrong-making features of the acts in those cases, and whether such features are present in God's case.

Disability: Anne wishes to have a child. She may select an embryo that will grow to develop a disability or a different embryo that will never have a disability. Either way the embryo will end up with a very good life. But the disabled embryo would suffer much more than the nondisabled one. Anne chooses the disabled embryo only because she desires the attention she would get from taking care of a disabled child.

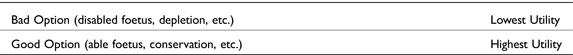

There are a number of plausible wrong-making features of Anne's act in Disability. One possibility concerns Anne's intentions. She intends to use the child's disability and suffering as a means to attention. That is wrong. Another possibility is that Anne has limited resources. She could only pick one of the children. She picked the one that would suffer more, and in doing so precluded picking the child that would suffer less. Another possibility is that utilitarianism is true. Anne had an alternative with a higher utility than picking the disabled child. And she chose the alternative with a lower hedonic utility.

Contrast this with God's policy of allowing suffering. God is not using the creature's suffering as a means to get attention. His intention is instead to make room for creatures with wonderful lives that could not have otherwise existed. God does not have limited resources like the mother in Disability. Making a creature like the animal that suffers does not preclude making any number of other creatures that do not suffer. He can allow for suffering but still make as many non-suffering creatures as He pleases. Furthermore, by picking the disabled foetus, Anne gets a child with a lower utility than she would have if she had picked the able foetus. But that is not the predicament God is in. For any creature without suffering that gets Him a particular utility, God can create a creature with suffering that gets Him the very same utility. On the other hand, God does fail to maximize utility. So if utilitarianism is true, then God acts wrongly. But the mother in Disability could have maximized utility and instead refrained. God, on the other hand, was unable to maximize utility. However many creatures God could have made with wonderful lives, He could have made even more. So the woman in Disability could have acted rightly. But God, given simple utilitarianism, could not. Given ought-implies-can, this means we either have to modify simple utilitarianism to accommodate God's predicament or toss out utilitarianism all together. Either way, it seems hard to blame God for failing to maximize utility when, for any of His alternatives, He has a better one.

Depletion: If we pick Depletion, over the next five hundred years everyone will enjoy a slightly better life than they would if we had picked Conservation. But after five hundred years everyone will have a life that is just barely worth living. If we pick Conservation, then everyone will have a very good life indefinitely. No one who exists after five hundred years if we choose Depletion would have existed if we had chosen Conservation.

Our choice in Depletion has some of the same wrong-making features as Anne's choice in Disability. But in contrast to Disability, there is another possible wrong-making feature. In Disability, the mother gave her child a very good life. But in Depletion, we picked the alternative that would yield lives barely worth living when we could have instead picked an alternative that would yield lives of great value. God in this respect, is more like the mother in Disability than us in Depletion. For, given the assumptions of the theodicy, God didn't end up giving those who suffer undeservedly lives barely worth living. He gives them all lives of infinite welfare after the post-Resurrection existence is taken into account.

Deal: Ben and Claire make an unbreakable deal the terms of which require them to conceive a child and then give it to a billionaire as a slave. In exchange they get $5000. The child's life as a slave will be very tough. But it will be slightly better than not existing at all. In the absence of such a contract, they would not have conceived the child.

Deal has some of the same wrong-making features as Disability and Depletion. An additional possible wrong-making feature of Deal is that Ben and Claire intend an evil. They intend that the child becomes a slave in exchange for money. The selfish good that comes from their act, they get $5000, does not outweigh the bad, their child becomes a slave. Contrast this with the consequences of the policy God adopts in the theodicy: an infinite number of creatures enjoy an infinitely good existence that they could not otherwise have enjoyed. And almost all of the creatures that suffer would not have existed if God had not adopted the relevant policy. These goods outweigh the bad of those creatures’ horrendous suffering.

In general, my thought is this: in the standard non-identity problem cases, subjects act for selfish reasons. They get a trivial good in exchange for picking people with a worse off future. And often the worse off future is one barely worth having. The people chosen to exist are not later compensated with infinite goods for their suffering. There are no extra people with wonderful lives that would not otherwise exist. The more you change the standard non-identity problem cases so that they match God's situation in the theodicy, the more the acts in those cases become permissible.

Objections and replies

First Objection: There are ways we should not allow people to be treated. Think about letting a child die. That is absolutely impermissible.

Reply: Pick any deontological theory. It will have the implication that it is permissible to allow a child to die. Take Kantianism. Imagine I could spare a child's life by treating my waiter as a mere means to get beer. Kantianism would require that I let the child die. If it is permissible for me to allow a child to die so that I may avoid treating my waiter as a mere means to beer, then it is permissible for God to allow a child to die and then be raised to eternal bliss so that He can create an infinite number of people with wonderful lives that He could not otherwise have created. This is especially true given that the child could not have existed at all if God had adopted a different policy. Furthermore, common-sense morality implies that it is permissible to allow a child to die. I sometimes purchase beer. I could instead use that money to feed a starving child. According to common-sense morality this is permissible. If it is permissible for me to let a child die for the sake of a beer, then it is permissible for God to allow a child to die and then be raised to eternal bliss for the sake of an infinite number of people with infinitely good lives who would not otherwise have existed (especially given that that child would not have existed if God had adopted a different policy). Take Thomson's (Reference Thomson1971) defence of abortion. According to her, it is permissible for Henry Fonda to allow a child to die so that he may avoid flying in from the West Coast and touching it. If it is permissible for Henry Fonda to allow a child to die so that he may avoid flying in from the West Coast and touching it, it is permissible for God to allow a child who could not otherwise have existed to die and be raised to eternal bliss so that God can create an infinite number of creatures with infinitely good lives that He could not otherwise have created. One might be a utilitarian like Peter Singer and deny that it is permissible for me to buy beer or refrain from treating my waiter as a mere means to beer or for Henry Fonda to stay on the West Coast. But it is not the allowing suffering that Singer objects to. It is the failing to maximize utility. And we have already seen that although Henry Fonda and I might be able to maximize utility, given God's power and His limitless resources, He is unable to do so.

Second Objection: It is true that God could not have created me, or any human, or most animals in our evolutionary history without allowing a lot of suffering. But he could have created duplicates of all of us that wouldn't have suffered. Since He could have created such duplicates, it was wrong for Him to create us.

Reply: I grant that God could have created duplicates of us that do not suffer. But I do not see how this observation implies that it was wrong for God to create us. After all, He didn't wrong us. We couldn't have existed if He had adopted a policy that ruled out suffering. And He didn't wrong our duplicates. For if He didn't make them, then they don't exist and their interests don't count. And if He did make them, then creating us too doesn't wrong them in any way. Furthermore, He doesn't make the world any worse by creating us. After all, given the Resurrection of the Dead, He is just adding to the world a lot of creatures with suffering up front but total existences of infinite value.

Third Objection: This entails that it is permissible for us to sit back and never intervene to prevent suffering.

Reply: If God commands us to do something, then we are obligated to do it. God commanded us to intervene to help others. So we are obligated to intervene. There are different ways in which a world can be beautiful and good. One way is that it can be a world in which God takes undeserved suffering, compensates it, and uses it to make creatures God could not otherwise have made. Another way in which a world can be good is that it contains creatures that look out for each other and intervene to prevent one another's suffering. God wants a world with both goods and not just one. So He commanded us to intervene. It is true that if we fail to intervene God will nevertheless make something beautiful out of the evil that we allow and that He could not otherwise have made. But that doesn't get us off the hook. Given the variety of goods God wants us to enjoy, we are still obligated to intervene.

Fourth Objection: I am approaching this topic in a superficial way and am not considering horrendous evils sufficiently concretely and vividly. If I were to do so, I would see that the theodicy doesn't work. Imagine that a woman's child dies at two weeks, leaving her nearly insane with grief. A few years later she has two more children. After seven years her husband comes home from work and dies before her eyes of a heart attack. Once again she is nearly insane with grief. Then her young five-year-old daughter has a stroke due to an aneurism which leaves her unable to move or speak ever again. The woman puts her daughter in a nursing home and slowly manages to rally. She is then diagnosed with breast cancer. The surgery is too late, she is slowly dying. Entirely broken, the woman descends into madness and begins have sex with her remaining child, who is 11. She dies at 48 in agony and terror, cursing God. There is a strong intuition that it would have been better for this woman never to have existed. Even if an eternity of the delights of heaven outweigh the badness of her earthly life, allowing her to be broken so horribly isn't compatible with the greatest love for her imaginable. That is wrong, regardless of the long-term good consequences for her. We might say either that her suffering cannot be compensated or that compensation doesn't make what happened to her permissible.

Reply: I am tormented by a mental disability. Although I have never ‘descended into madness’ like the woman in the objector's example, I think I have caught glimpses of what it would be like. It is indeed horrifying. Still, if I were given the choice to either have my mental disability utterly consume me like the woman in the objector's example and then be compensated with eternal bliss, or to have never existed, I would not hesitate to choose the woman's life and to be completely broken and then healed. I would rather God adopt a policy that allows for horrendous evil but makes room for me, my loved ones, and the woman in the objector's example than a policy that purges the world of such horrors but excludes us. I find the idea that God would make room for beings like me that could only exist alongside a policy allowing for suffering to be very meaningful and beautiful. I bristle a bit at the assertion that those with lives containing horrors would have been better off not being created or that God's goodness would preclude their existence.

Fifth Objection: I am assuming that there is a distinction between doing and allowing and that while it might not be permissible for God to directly cause the relevant suffering it is permissible for Him to allow it. Someone might note that the distinction between doing and allowing is controversial. Others might suggest that although there is such a distinction, God is weird in certain ways that make the distinction morally irrelevant in His particular case.

Reply: This theodicy does not rely on the distinction between doing and allowing. It relies instead on this disjunction: either there is a distinction between doing and allowing that is morally relevant to God's acts or God's permissible alternatives are expanded. Think about euthanasia. When people debate whether there is a difference between doing and allowing in the context of euthanasia, they do not think that killing a sick patient is wrong so therefore allowing them to die is wrong too. What they think is that the lack of a distinction between doing and allowing expands one's permissible alternatives. They argue that since allowing a patient to die is permissible, killing them is permissible too. Similarly, if there is no distinction between doing and allowing (or if it is not morally relevant in God's case), then it is permissible for God to directly cause a creature to suffer in order to create other wonderful creatures that He could not have otherwise created and as long as He compensates the relevant creature. His permissible options are expanded and not restricted by the lack of a distinction between doing and allowing. Just as our permissible options are expanded in other contexts in which the distinction is deemed irrelevant.

Sixth Objection: Suppose Alice and Bob have a genetic condition ensuring that any child of theirs will suffer horrendously. Nonetheless, they choose to engage in marital union. Moments after that, two scrupulously honest aliens show up. They both predict that fertilization will occur. The first alien offers to repair the gametes prior to fertilization, at no cost of any sort and with no further side-effects. The second alien offers the couple $5000 if they have a child that suffers horrendously. The couple refuse the first alien's offer in order to gain $5000. They clearly do wrong in intentionally allowing the suffering. My theodicy implies that this is permissible. But it is not.

Reply: I deny that my theodicy implies that this is permissible. Remember, I say that five conditions together are sufficient for it to be permissible for God to allow horrendous suffering. Among these are the condition that God allows it at least in part in order to create a lot of wonderful creatures that He could not otherwise have created. This is different from the couple in the objectors’ example. They choose to allow suffering for their child in order to gain $5000. Another condition was that God compensate the sufferer with an infinitely good afterlife. But the couple does not provide such compensation for their child. Another condition is that the sufferer would not have existed if God had not allowed any previous instances of horrendous suffering. But the couple's child could have existed without any previous allowing of such suffering by his parents.

Seventh Objection: Do I really think this theodicy explains all of the actual world's suffering?

Reply: No. I don't think it explains why God allows the suffering of the first creature that suffers in our evolutionary history. Or, at the very least, I don't think the explanation is as good as it is for creatures like us and like Rowe's fawn. One might think it doesn't explain the suffering of the last generation of creatures. But I see no problem with allowing that such creatures do not suffer or that God just keeps making creatures forever.

Eighth Objection: It is unclear how this theodicy differs from the more general appeal to the idea that an infinitely valuable afterlife can counterbalance temporary suffering on earth for any creature. This is already on offer, so it is unclear what my original contribution is.

Reply: The original contribution is this: just counterbalancing suffering isn't sufficient for theodicy. The creature that suffered can complain that although it was compensated for its suffering, there was no point in allowing it to suffer because it, and all other creatures, could have received all the same goods if God had not allowed any suffering. But my theodicy addresses this worry. The suffering occurred because it was necessary for creating beautiful creatures that God could not have otherwise created. And if God had adopted a policy of preventing suffering, the creature that suffered would not have existed. So in the case of my theodicy, the creature can't complain that the suffering was unnecessary for any other good. And the creature can't complain that it could have existed if God hadn't adopted a policy of allowing for suffering.

Ninth Objection: This theodicy opens God up to exploitation. Imagine I have chronic horrendous pain. In order to get rid of the pain, I build a spaceship that goes at 99.9% of the speed of light into the emptiness of space. No one will follow me. I have no radio. As soon as I am past the point of no return, whether my pain continues or not makes no difference to the existence of any conscious creature. So, God has to cure my pain! Yet it seems that I shouldn't be able to force God to do a miracle.

Reply: Remember that this theodicy is merely a set of sufficient conditions for God to be permitted to allow horrendous evil. It is not a set of necessary conditions. So there may be some other good reason for God to allow me to continue to suffer in this case. Furthermore, distinguish between two versions of the objection. First, the worry might be that it is metaphysically impossible for God to be exploited. Second, the worry might be that while it might be metaphysically possible for God to be exploited, He wouldn't allow it to actually happen. I don't share the intuition behind any of these worries. And given the kind of humility God displayed on the Cross, it seems to me that God would not be so concerned with preventing His own exploitation that it was ruled out as an impossibility.

Tenth Objection: What about Hell? Does this theodicy require universalism? Does it conflict with the traditional view about Hell?

Reply: To lay my cards on the table, I am attracted to a certain sort of universalism. I'm not attracted to the kind that says there are a lot of fundamentally different ways to get to God and everyone gets in in their own fundamentally different way. I think there is one fundamental way, through Jesus’ work on the Cross. But I'm attracted to the idea that everyone gets in through that way. That being said, I'm not completely confident about universalism. And I think there might be a way for the proponent of an eternal Hell to adapt the theodicy. In particular, I've been trying to give just one set of sufficient conditions for the existence of undeserved horrendous evil. But there could be other such conditions. And I haven't said anything about deserved horrendous evil. So maybe the person who is more a fan of an eternal Hell than I am could find some wiggle room to fit Hell into this picture in one of those spots. But I'm not at all confident that they can. And I won't do the work for them. I'll leave it to the fans of Hell to spell out how such an approach would go. In any case, even for the fan of Hell, it makes a huge dent in the problem of evil. That is still progress.

Appendix: Contrast with Vitale, Mawson, and Adams

Vince Vitale has published an important paper (2017) and book (2020) about the sort of theodicy I discuss in this article. Anyone who has read Vitale will know that he has already covered a lot of the ground that I cover here. An important forerunner of this sort of view is Tim Mawson (Reference Mawson1999). He also appeals to the idea that God could not have made us without allowing horrendous evils and discusses it in connection with Parfit. Finally, Robert Adams is, as far as I can tell, the first contemporary figure to articulate the core idea behind this sort of theodicy. Given that this view is already present in the literature, I owe an explanation of what I add and what I think is new about my approach.

Utilitarianism

One difference between our approaches is that all of these authors reject utilitarianism and think the theodicy in question is incompatible with it. Vitale (Reference Vitale2020, 54) explicitly rejects ‘the broadly utilitarian assumption that a metric can be used to weigh the moral significance of consequences’. He says that:

Underlying this approach to theodicy is a resistance to invoking value maximization as the ethical or rational ideal. … According to Non-Identity Theodicy, God is not just after benefits for objects of love, but rather he is after the individuals who are the objects of love. He is after them because he finds them lovable, and lovableness as a quality is very different from a measurement of value. (Vitale (2017), 277–228)

And he says:

Because God is gracious, his desire to love us is not on the condition that we are more valuable than other creatures he could have created or that our existence allows for the maximization of overall world value. On the contrary, reflection on the virtue of grace suggests that desiring to create and love persons vulnerable to significant evil can be just as fitting with the abundance of divine generosity as desiring to create and love the most valuable, most useful, or most well-off persons God could create. (Vitale (2020), 167–168)

Mawson puts it this way:

Finally, the falsity of at least some forms of consequentialism has been assumed in order to enable me to reach my conclusion and it is thus worth pointing out, before I conclude, how my argument crucially depends on this assumption and how this assumption could be defended by the classical theist. (Mawson (Reference Mawson1999, 337)

Robert Adams is clear that he rejects utilitarianism and sees that rejection as essential to his argument. As he puts it:

If we apply an act-utilitarian standard of moral goodness, we will have to accept [the conclusion Adams wants to avoid which is that God must create the best world]. For by act-utilitarian standards it is a moral obligation to bring about the best state of affairs that one can … I believe that utilitarian views are not typical of the Judeo-Christian ethical tradition, although Leibniz is by no means the only Christian utilitarian. In this essay I shall assume that we are working with standards of moral goodness which are not utilitarian. (Adams (Reference Adams1972), 318)

I disagree with these authors. I think the sort of theodicy we are attracted to is an especially comfortable fit with utilitarianism. Here is why: the utilitarian diagnoses of non-identity type cases all depend on the cases being ones in which subjects have mutually exclusive alternatives with different utilities. We can represent it this way:

And so the utilitarian diagnosis of what is wrong in these sorts of cases is this: the subjects in non-identity cases pick an alternative that excludes the maximization of utility. They have two options. One has a lower utility. The other has a higher utility. The subjects in the relevant cases pick the option with the lower utility to the exclusion of picking the other alternative that maximizes utility. And for that reason those subjects’ acts are wrong.

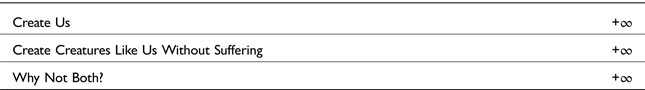

But this is different from the predicament God finds Himself in before deciding what to create in the actual world. Pick any utility you want, say +∞. God's alternatives look more like this:

There are two things to note here: First, for any value of a world or a life without horrendous suffering that God can create, He can get a world or life with horrendous suffering that has the same utility. Whether there is suffering up front for the creatures God makes, the utility can be the same. Whether God creates both sorts of creatures, the utility can be the same. And, given utilitarianism, if there is no difference in utility, there is no difference in the morality of the act. So that is a relevant difference between God's predicament in the actual world and the predicament of the subjects in Parfit's examples.

Second, God is not like the mother who must choose between the disabled foetus and the able foetus. Nor is He like the society choosing either Depletion only or Conservation only. His alternatives are not exclusive in exactly this way and He has many more options. He can create an infinite number of creatures like us that suffer horrors early on but have infinitely valuable lives. And He can create an infinite number of creatures like us that do not suffer and have infinitely valuable lives. Creating one sort of creature does not preclude creating the other sort. And so He is not creating us to the exclusion of creating better creatures or creatures with better lives. So that is another relevant difference between God's predicament and that of the subjects in Parfit's examples.

Now, there are certainly interesting puzzles for the utilitarian here. There is an issue about how the utilitarian should evaluate God's acts given that for any utility God can get He can instead get a higher one. But that is not a complication that the theodicy introduces. It is an independent puzzle for the proponent of utilitarianism.Footnote 2

So one thing I think I have to contribute to this literature is the result that this sort of theodicy is a very natural fit with utilitarianism.Footnote 3 The main figures in this literature think utilitarianism is off the table. They think you have to abandon utilitarianism to get the theodicy to work. But you do not. The theodicy and utilitarianism go well together.

Depletion and Conservation

Those of us who are attracted to this sort of theodicy must contend with Parfit's Depletion and Conservation example. We need to give a plausible diagnosis of why picking Depletion is wrong that does not commit us to holding that God's act in the theodicy is wrong. I disagree with the diagnoses given by Vitale and Mawson. And Adams does not discuss Depletion and Conservation. Consider Vitale's diagnosis:

Even if, in creating, God does not wrong anyone, by creating a universe with more suffering than other universes God could have created, hasn't God shown a defect in character similar to the defect we show when, by depleting resources now, we knowingly cause the existence of future people who suffer more than those who would have existed had we not depleted? It might seem so initially, but there are relevant disanalogies. It is true that the predictable result that we will cause to exist persons who suffer more gives us and God some prima facie reason against depleting resources and against creating a world with greater suffering. However, according to Adams, God is able to weigh that reason against another reason in favor—his desire to love and bestow grace upon specific individuals. As human depleters, we cannot appeal to this counterreason. Our choice for future generations is constrained by our greatly limited predictive ability. The result is that we are too epistemologically challenged to know enough about the persons that will result from our depletion to cite our desire to be gracious to them as a depletion-justifying motivation. (Vitale (Reference Vitale2020), 174)

So Vitale's idea is this: when God picks a less good world with suffering over a better world without suffering, He does so because He has in mind very specific people whom He wants to create and love. He can do this because He is omniscient. We are not omniscient. We can't predict exactly what the people who will exist if we choose Depletion will be like. So we can't have the same motive as God. That is why what we do in picking Depletion is wrong but what God does in creating a world like ours with suffering is permissible.

I do not accept this diagnosis of Parfit's example. First, imagine that before we make our decision, we are able to look into the different possible futures and see exactly whom we would create if we picked Depletion and exactly whom we would create if we picked Conservation. Imagine that on the basis of this we pick Depletion because we want to give those people lives. We see the people who would exist if we choose Depletion in all of their life-barely-worth-living detail. And we chose Depletion just because we want to give them, those particular people, that life. In that case I think we have done something very wrong. I don't think that gets us off the hook for picking Depletion. And so I don't think God picking people who suffer in their precise details gets God off the hook for allowing horrendous evils.

Second, I don't think that knowing who will be benefited in precise detail is necessary for ‘bestowing grace’ on someone. Imagine you write a cheque to UNICEF. You know it is going to help feed someone. You don't know much other than that. But you write the cheque because you want to help that person, whoever it turns out to be. It seems to me that you have bestowed grace on the people who benefit from your donation even though you are unable to conceptualize them in their precise details and predict who they will be. And, in the same way, if that is really our motive, to get the people who will only exist if we choose Depletion and give them a life, then it seems to me that we do bestow grace in the relevant variant of Parfit's example. But picking Depletion still seems very wrong. And so I don't think Vitale's diagnosis gets God off the hook for picking creatures like us that suffer horrendous evils.

Next, consider Mawson's (Reference Mawson1999, 38) diagnosis of Parfit's example about Depletion and Conservation.

Adopting Parfit's form of consequentialism would enable us to justify a preference for conservation over depletion and this is what he proposes we do. However, it is possible for the classical theist to justify his or her preference for conservation over depletion (if this is the preference he or she has) without adopting a form of consequentialism that would vitiate my argument.

Given that classical theists are defined by their belief in an everlasting God, it is open for them to suggest that it is simply not true that, by the time the bad effects of a policy of depletion come to be felt, no-one who then exists would have existed had the policy of conservation been followed instead. God will exist regardless of which policy is followed and, the classical theist may maintain, He would be wronged if one depleted the earth's resources. He has forbidden such things and thus one ought not to be morally indifferent about them. One has wronged someone, in a sense made them ‘worse off’, if they have, from a position of authority, given an instruction on what would otherwise have been a morally indifferent issue and have had that instruction ignored. The classical theist can assert that God has issued some instructions about what is to constitute appropriate use and inappropriate abuse of His creation and, in virtue of the moral indifference of the issue (logically) prior to his doing so and His being the creator of the universe, He has the authority to create obligations of stewardship towards it in this way. This ‘partial divine command theory’ would remove the need for an acceptance of the form of consequentialism internecine to my argument (by providing a solution to what Parfit calls ‘the identity problem’) and, despite its rather ad hoc patchwork feel, can obviously be adapted to meet any new objections to my argument from this quarter.

So Mawson's idea is this: God will exist whether we choose Depletion or Conservation. Choosing Depletion violates His commands. So He will be wronged if we choose Depletion.

I do not accept this diagnosis of Parfit's example. First, an implication of this approach is that if God didn't exist, it would be permissible for us to choose Depletion. I understand the idea that if God doesn't exist, then everything is permitted. But I don't understand the idea that if God doesn't exist, then regular morality (in general) is still true; but Depletion (in particular) is now permitted. It seems like something wrong is done not just because God's command is violated. It seems like there is something wrong with the sort of world we chose to create in Depletion.

Second, although God exists, He hasn't given us a command one way or another about what to choose in Depletion and Conservation. None of the Ten Commandments proclaim: ‘Thou shalt choose Conservation rather than Depletion in Parfit's example.’ So God exists. But choosing Depletion wouldn't violate his commands. Or, more cautiously, maybe what I should say is instead this: if picking Depletion violates God's commands, it will be a violation by way of implication. And the proponent of Mawson's strategy has an obligation to identify the relevant command and spell out the implication for us that picking Depletion violates. Otherwise, the strategy is incomplete. And I would place my bets that when we find the relevant command, we will see God's deeper motivation for that command. And I think it will be that deeper motivation on God's part that we can cite for why it is wrong to pick Depletion.

I would now like to explain why I think my approach to this topic is different from and improves upon Vitale's and Mawson's. Earlier in the article, I offered four diagnoses of what might be going on in Depletion and Conservation. First, one thing that might be going on is that utilitarianism is true. And in picking Depletion we get a lower utility than when we pick Conservation. I said that you can't pin that complaint on God because for any utility God gets without suffering, He can get the same utility with suffering. So it can't be that what God did is wrong because picking a world with horrendous suffering in it gets Him a lower utility than picking a world with horrendous suffering. They get Him the same utility. So utilitarianism lets God off the hook.

Second, I said that what might be going on in this case is that in picking Depletion we choose a world full of creatures with existences that are barely worth living over a world with creatures with wonderful flourishing lives. But that isn't the predicament God faces in the actual world. God hasn't given us a world with lives just barely worth living. God has given us wonderful lives. For some of us, we enjoy wonderful lives in the here and now. For some of us, we suffer horrendously and undeservedly in the here and now. For some of us, it is a mix. But, given Jesus’ work on the Cross, we will be risen to glory when He returns. So in that case the diagnosis of Depletion allows that God's act is permissible. What God is doing and has done through Christ's work on the Cross is in this way very different from what the subject in Parfit's example does by picking Depletion.

Third, I said that what we do in Depletion might be wrong in part because our motives are selfish. We want to have slightly more awesome lives for ourselves. So we make the world worse to get it. But that doesn't apply to God. God doesn't allow horrendous evils so that He can get a slightly better yacht or fancier beer. God allows horrendous evils so that He can create a lot of beautiful creatures with wonderful lives that He couldn't have otherwise created. And if He had a policy of banning horrendous evil, none of us would have existed. (I do note that Vitale makes a similar point about selfish motives in his discussion. And although Adams does not discuss Depletion and Conservation, he makes a similar point about selfishness in his discussion of picking the disabled foetus. So this aspect of my diagnosis is not original.).

Fourth, I said that maybe Depletion is wrong because the creatures in Depletion are created in exclusion of the creation of the creatures in Conservation. But as I pointed out, God's alternatives are not exclusive in this way. He can create the creatures that suffer (us) as well as the creatures that do not suffer. And He can create as many of each as He likes. He can do both. To put it in an overly anthropomorphic way: maybe after God created countless creatures with no horrendous suffering at all he thought ‘Why don't I give this other sort of creature, the sort that can only exist with horrendous suffering, a chance to live too?’

So we have four things that I think might be going on in Depletion and Conservation. If I am right in speculating that some combination of them together turns out to be the correct diagnosis, then God is off the hook. What He is doing in the actual world does not have the relevant wrong-making features. On the other hand, if you change Depletion and Conservation so that picking Depletion has all the features of God's situation in the actual world, then I will say you've changed the case in such a way that we are off the hook for picking Depletion. Imagine that picking Depletion has exactly the same utility as picking Conservation, imagine that the people who exist because we choose Depletion will have wonderful lives rather than lives barely worth living, imagine that we do not choose Depletion for selfish reasons, and imagine that we can choose both Depletion and Conservation and have already chosen Conservation a lot of times. In that case you've made choosing Depletion relevantly like God's act in the theodicy. But you've also made it permissible, and indeed exceedingly wonderful, to choose Depletion.

So one thing I think I have to contribute to the literature on this topic is an improved diagnosis of what is going on in Depletion and Conservation and why God is off the hook for allowing horrendous evils in light of that diagnosis. I agree with the general drift of Vitale and Mawson's theodicies. And I am inspired by their work on this topic. But I don't think that the diagnoses they give of Depletion and Conservation are plausible. And I think my diagnosis is. I think I help raise the plausibility of the Adams-inspired theodicy that we together endorse.

Doing and allowing

Vitale and I are different in our approach to the distinction between doing and allowing. As Vitale (Reference Vitale2020, 226) puts it:

[T]here is an overemphasis in theodicy on the moral distinction between causing and permitting. Even bracketing deep skepticism about this distinction in contemporary moral philosophy, reflection on a variety of examples shows that whatever moral difference this distinction might make in normal circumstances, it makes little at best where horrendous harm seeks purely beneficial justification. Moreover, the conceptual space between the related concepts of doing and allowing is markedly diminished when the agent under consideration is a divine being who is at every moment doing what it takes to sustain all things.

So I take Vitale to be making two points here. First, if there is a distinction between doing and allowing, it doesn't apply in the case of horrendous evils. Second, if there is a distinction between doing and allowing, it doesn't apply to God and so it can't be employed to get God off the hook for allowing horrendous evil.

I disagree with Vitale on both counts. Let me take them in reverse order. First, consider the possibility that God is weird in such a way that the doing/allowing distinction applies to us but not to Him. Notice that people who are sceptical of the distinction between doing and allowing tend to be utilitarians. They tend to think that only consequences matter. And they tend to think that removing the distinction expands our permissible alternatives in certain ways. Take euthanasia. People who reject the distinction in question think we can kill suffering patients because there is no difference between killing and letting die. It is the people who think that there is a distinction who think euthanasia is impermissible. So if the distinction between doing and allowing does not apply to God, then it seems to me the natural thing to say is that His permissible alternatives are expanded as they are with us in the euthanasia debate. What rejection of the distinction with respect to God would imply, it seems to me, is that God can both permit and cause undeserved horrendous evils. So I think accepting the distinction between doing and allowing is actually harder on God. And rejecting the distinction makes things easier on God and easier for those of us who are engaged in this kind of theodicy.

Second, I disagree with Vitale's claim that even if there is a doing/allowing distinction, it does not apply to horrendous evils. Consider a pair of examples:

Letting Die: Over the course of four years you spend $3.4 K on video games, fancy beer, dental work, internet service, and books for your children by pressing buttons when you could have pressed other buttons and spent that money to save a child from a painful death.

Killing: Over the course of four years you get $3.4 K in video games, fancy beer, dental work, internet service, and books for your children in exchange for pressing some buttons that cause a child to die painfully.

In these cases, a horrendous evil occurs. A child dies horrifically. But in one case you perpetrate the horrendous evil and in the other case you merely allow it. We all continuously act as is described in Letting Die. And that is morally permissible.Footnote 4 Few of us have acted as described in Killing. And to do so would be, to put it mildly, deeply wrong. It seems clear that causing a horrendous evil as in Killing is worse than allowing a horrendous evil as in Letting Die. Only a hardcore utilitarian would reject the distinction. And if they did, then it wouldn't be the allowing of horrendous evils that they object to. It would instead be the failing to maximize utility. Allowing or doing horrendous evils would be fine as long as it is in the service of maximizing utility. So either way, whether there is a distinction between doing and allowing or not, allowing horrendous evils is permissible.

Vitale also points out that some contemporary philosophers are deeply sceptical of the doing/allowing distinction. I have no idea what the distribution of proponents to opponents of the distinction is. But, however the numbers tally up, I am confident that most contemporary philosophers are even more sceptical of the prospects of theodicy than they are of the doing/allowing distinction. So if we are in the game of giving theodicies at all, as Vitale and I are, then we are also in the game of giving a minority report. And, if we are already in that game, I see no reason to think we can't give a minority report in favour of the doing and allowing distinction as well.

So one thing I think I add to this literature is the point that the doing/allowing distinction is actually very morally relevant. Some figures think that it is not relevant or not relevant to God or not relevant to horrors. But I think it is. I think we are permitted to allow horrendous evils. I think God is too. And I think scepticism about the doing/allowing distinction would only make things easier on those of us who are attracted to this sort of theodicy.

The relevance of shape to the value of lives and worlds

A related issue on which I differ from Vitale, Mawson, and Adams concerns how we see the value of our lives as compared to the value of the lives of otherwise similar creatures God could have made that do not suffer. Vitale thinks such creatures have better lives and lives with more value than we do. As we have seen, Vitale constantly says that God need not make the most valuable creatures or the most excellent creatures. He can make us instead even though our lives are not as valuable, or we are not as excellent, etc. Mawson and Adams make similar claims. So they think that by creating us God is settling. He could have done better than us. We are defective in a certain way.

I strongly disagree with this. I do not think the total value of our lives is less than that of our otherwise similar non-suffering counterparts. And I think our lives and stories and the world we inhabit are beautiful and valuable in a way that is different from the beauty of the lives of and worlds inhabited by creatures that do not suffer horrendously. So, as I say earlier in the article, I don't think that God is settling for less by making us rather than, or in addition to, our counterparts. Instead, I think that taking creatures God could not have made without allowing them to suffer horrendous evils and then healing them and making them infinitely good and beautiful is valuable in a different way from taking creatures that are already excellent and not in need of healing and leaving them that way. I do not think the presence of horrendous suffering in our world makes it any worse than an otherwise similar world without suffering.

Here I am relying on some insights from Thomas Metcalf's (Reference Metcalf2020) theodicy. I think the sort of theodicy Vitale and I favour works better when combined with the Metcalf-style theodicy. And I think the Metcalf-style theodicy works better when combined with the approach Vitale and I favour. So one thing I think I am doing that is new in this article is combining the approaches for an improved theodicy.

A problem for Mawson's theodicy

While Mawson (Reference Mawson1999) is an important forerunner to the sort of theodicy that Vitale and I advocate, he does things quite a bit differently than we do. One thing I want to do is contribute to the literature on this topic by arguing that the approach Vitale and I take is an improvement on the Mawson-style approach.

Mawson's theodicy is disjunctive: if we have libertarian freewill, then it seems to provide an explanation of why God would allow evil. But what if libertarianism is false? What if determinism is true? What can we make of why God allows evil in that case? Given determinism, Mawson thinks we can explain why God allows evil by a different route. And the core thought that drives Mawson's argument is the core thought that drives my approach and Vitale's. In particular, God couldn't have made us without allowing a lot of evils. As Mawson (Reference Mawson1999, 340) puts it:

Thus I conclude that, given the truth of determinism and the falsity of some forms of consequentialism, God would have satisfied (at the moment of His choice whether or not to create this universe) a sufficient condition for being morally indifferent; whichever way He decided, He could not fail to do for any creature who would actually exist the very best that He could. Thus, in choosing to create this universe, He cannot be more morally praiseworthy or blameworthy than He would have been had He not done so.

Like Vitale and me, Mawson thinks that God could not have made us without allowing a lot of evil leading up to our existence. But he advocates an even stronger view. In particular, he thinks that God can't even prevent the horrendous evil that happens to such creatures. As Mawson (Reference Mawson1999, 335) puts it:

If our universe is deterministic, then (per impossibile, I shall argue) for God to have put any of us in a better situation than that in which we in fact find or shall find ourselves would require him either to effect a change in the initial conditions of the universe and/or the laws of nature operating on them or to perform miracles in the Humean sense of interrupting its deterministic development at later times. Considering these options in reverse order, miraculous intervention whenever something less good than the best thing which logically could happen to a creature was about to happen would lead to such a breakdown in the laws of nature – one might think particularly of the biological laws of evolution, red in tooth and claw – as to be straightforwardly incompatible with determinism. Given the assumption of the truth of determinism under which we are working, this can therefore be ruled out. (Mawson (1999), 335)

And just below that he says:

The only way for God to avoid the causally necessitated lack of stars, planets, creatures and humans would be for Him to constantly miraculously interrupt such a universe's deterministic development, but, given our assumption of determinism, we have ruled this option out … God could not have created any of us in a better deterministic universe than that which we find ourselves in. This is the best of all possible universes for us. (ibid., 336)

So Mawson's idea is this: there are two possibilities. Either libertarianism is true or determinism is true. Suppose libertarianism is true, then we get the freewill theodicy. Suppose determinism is true, then God can't ever intervene. Because if God did intervene, then determinism wouldn't be true. Since those are the only two possibilities, we've got a theodicy either way.

I think there is a problem with Mawson's approach. I think that libertarianism and determinism are not the only two options. If libertarianism is false, God can still make an indeterministic world. The falsity of libertarianism would just mean that free choices need not be indeterministic. Maybe that is because we lack freewill altogether. Or maybe it is because compatibilism is true and free choices can occur as either indeterministic or deterministic processes. So this leaves the person who suffers from horrendous evil with the following complaint: ‘Sure, libertarianism about freewill is false. I get that. But at the same time, I don't see why you didn't just intervene and use a miracle or set up indeterministic laws that would prevent my horrendous suffering. The falsity of libertarianism doesn't imply that you can't step in to prevent evil or have indeterministic laws that do so. So why didn't you do that? Why am I suffering horrendously?’

I do not think my approach has this problem. I think that the theist may assume that Assembly Origin Essentialism is true. God can change the laws of nature. But He can't change the metaphysical laws. Assembly Origin Essentialism is a metaphysical law. And so God can't change it. And, given Assembly Origin Essentialism, if God hadn't allowed horrendous evil, the suffering creature couldn't have existed. If He changed anything that happened before your conception, He wouldn't have got you. He would have got a mere duplicate of you. So the difference between Mawson, on the one hand, and me and, on the other, is that in Mawson's system, God just has to violate a physical law or set up indeterministic laws in order to get the relevant creatures to avoid horrendous evil. And He can do it easily enough. But on the view that Vitale and I share, God has to violate a metaphysical law to get a world without any horrendous evil that contains that creature. And although God can violate physical laws, He cannot violate metaphysical ones. Furthermore, if we were to accept Mawson's view that God does not intervene at all, that would imply that God never performs miracles. But God does perform miracles. The sort of approach Vitale and I advocate can accommodate this datum. But Mawson's approach has trouble accommodating it.

So one thing I think that I am doing in this article that is new is giving more attention to Mawson's underappreciated article, showing that it is connected with the Vitale/Adams approach, offering criticism, and showing how my approach and the Vitale approach improves and builds upon Mawson's.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this article were presented at CU Boulder's Center for Values and Social Policy and at The New Theists Paper Workshop. I am very grateful to Harriet Baber, Matthew Baddorf, David Boonin, Dustin Crummett, Todd DeRose, Sam Director, Chris Freiman, Renaud-Phillipe Garner, Bob Gruber, Chris Heathwood, Nathan Howard, Mike Huemer, Justin Klockseim, Felipe Leon, Justin Mooney, Yujin Nagasawa, Alastair Norcross, Caleb Pearl, Kenny Pearce, Alex Pruss, Josh Rasmussen, Daniel Rubio, Jim Stone, Philip Swenson, Brian Talbot, Michael Tooley, Kevin Vallier, Craig White, Liz Jackson Withorn, and various anonymous referees. Special thanks to the referees for Religious Studies. I know there are other people who helped me with the article that I am forgetting. If you are one of those people, please let me know and I will buy you a beer. But, before you take me up on the offer, do be aware that the money I spend on your beer could instead be used to prevent a horrendous evil.