INTRODUCTION

On 7 April 1690, at two o'clock in the afternoon, Étienne Baluze (1630–1718) delivered the inaugural lecture of his new course on canon law at the Collège Royal in Paris. Baluze, an accomplished author, editor, and historian, spoke for the first time officially as the professor of canon law, a position he had been appointed to by Louis XIV (r. 1638–1715) a few months before. Canon law had always held special importance in France, supporting Gallican positions in the country's perennial conflict with Rome. Many French Catholics believed that the pope's authority was limited to the spiritual realm, while decisions on local ecclesiastical customs and jurisdictional matters belonged to the state.Footnote 1 Baluze himself was no stranger to jobs whose holders were stretched by the claims of erudition, scholarship, and politics. He had previously served as the secretary to the archbishop of Toulouse and Paris, Pierre de Marca, himself a prolific and opinionated Gallican author, and later served as librarian to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV's prime minister. Baluze embodied the institutionalized version of Catholic confessional erudition characteristic of early modern France.Footnote 2

Before sketching the plan of his course, Baluze introduced the audience to Gratian's Decretum (Decree, ca. 1140) as the central text of the Church's legal tradition: “When I was considering how to perform properly my duty as the professor of canon law, recently bestowed upon me, I thought nothing more appropriate to fulfill my task, [dear] listeners, than to explain to you the work which is commonly known as Gratian's Decretum, for it contains the sources and foundations of our law. From it we draw the principles of good life and study, and take weapons for use against heretics and schismatics.”Footnote 3 Baluze thus reminded his audience that one studied canon law for scholarly, moral, and religious goals, even if in seventeenth-century France it was examined primarily to argue for the sacrosanct legitimacy of her monarchs’ privileges. The lecture pointed to the continuing significance of Gratian's Decretum, pedagogical and practical.

Next Baluze revealed the convoluted nature of the Decretum, notorious for its multilayered structure, which often caused inconsistencies. Gratian's Decretum had always been a composite text, an anthology rather than a coherent code, resembling parts of the Roman Corpus Iuris. It was first compiled in Bologna in the 1140s, seemingly as a teaching collection of legal texts, by a jurist and university tutor, Gratianus (d. ca. 1145).Footnote 4 The heterogenous amalgam of conciliar canons, pontifical letters (decretals), excerpts from Church Fathers, ecclesiastical histories, and apostolic traditions of varied origins had been prone to manipulation over centuries. It had also suffered at the hands of inaccurate scribes. Baluze taught: “This work is truly full of errors, but not because of Gratian's trickery, as some have believed, but rather because of those whose mistakes he adopted as his own. Those men had either been fooled themselves, or they deliberately wanted to deceive others.”Footnote 5 As time passed, Gratian's collection had grown with additions and commentaries. Many were integrated into the text and blurred the distinction between the original compilation and later apparatus.

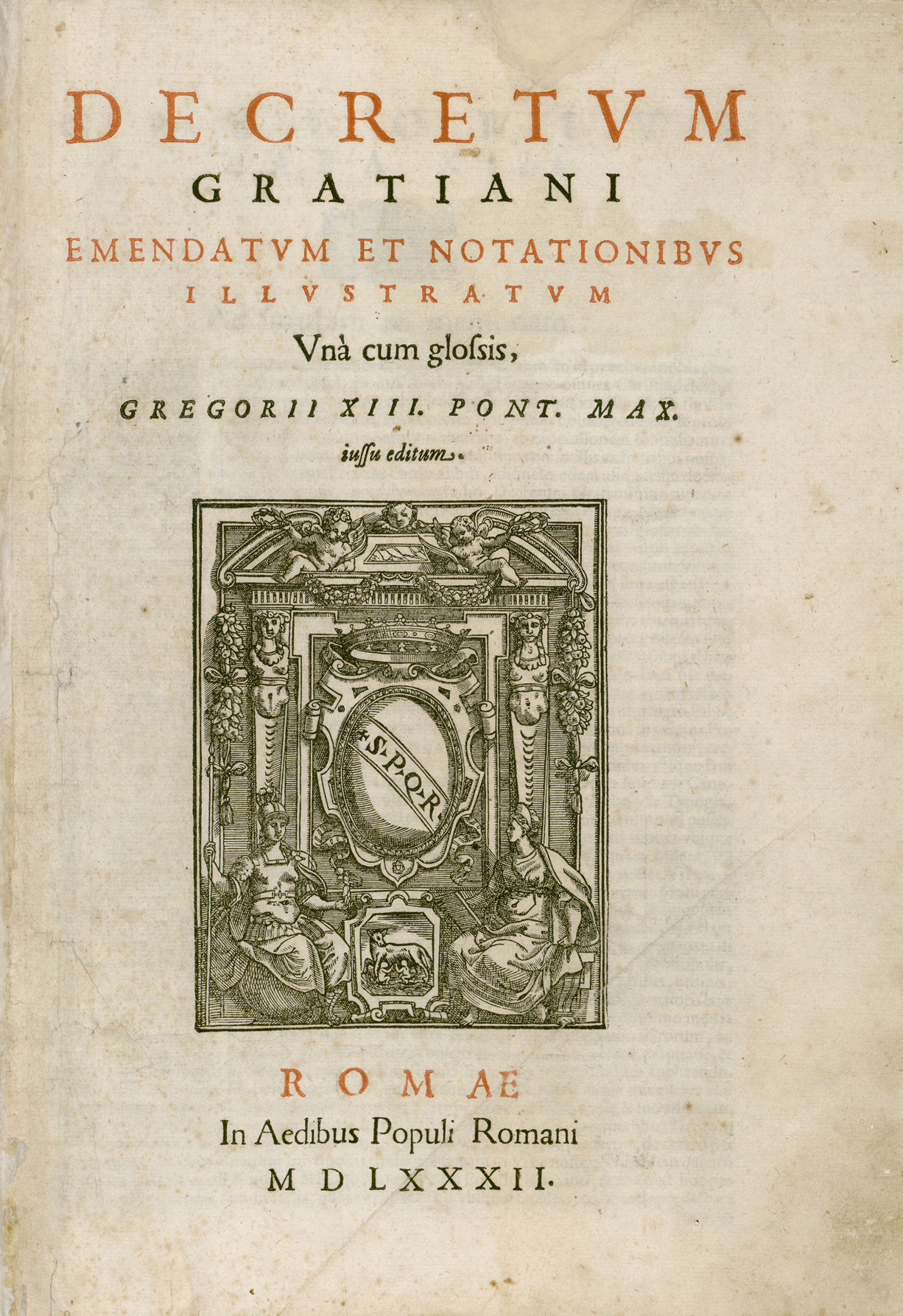

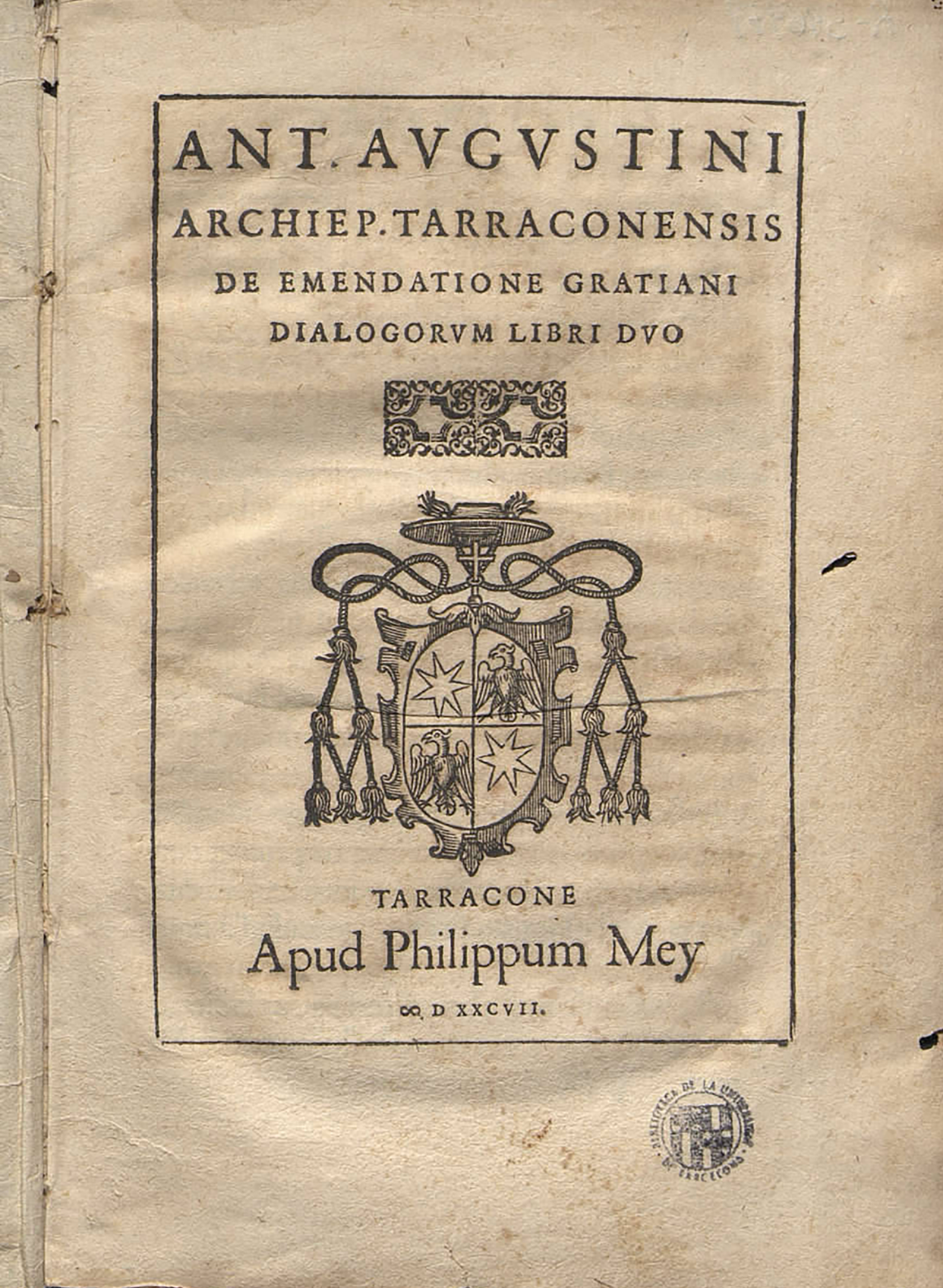

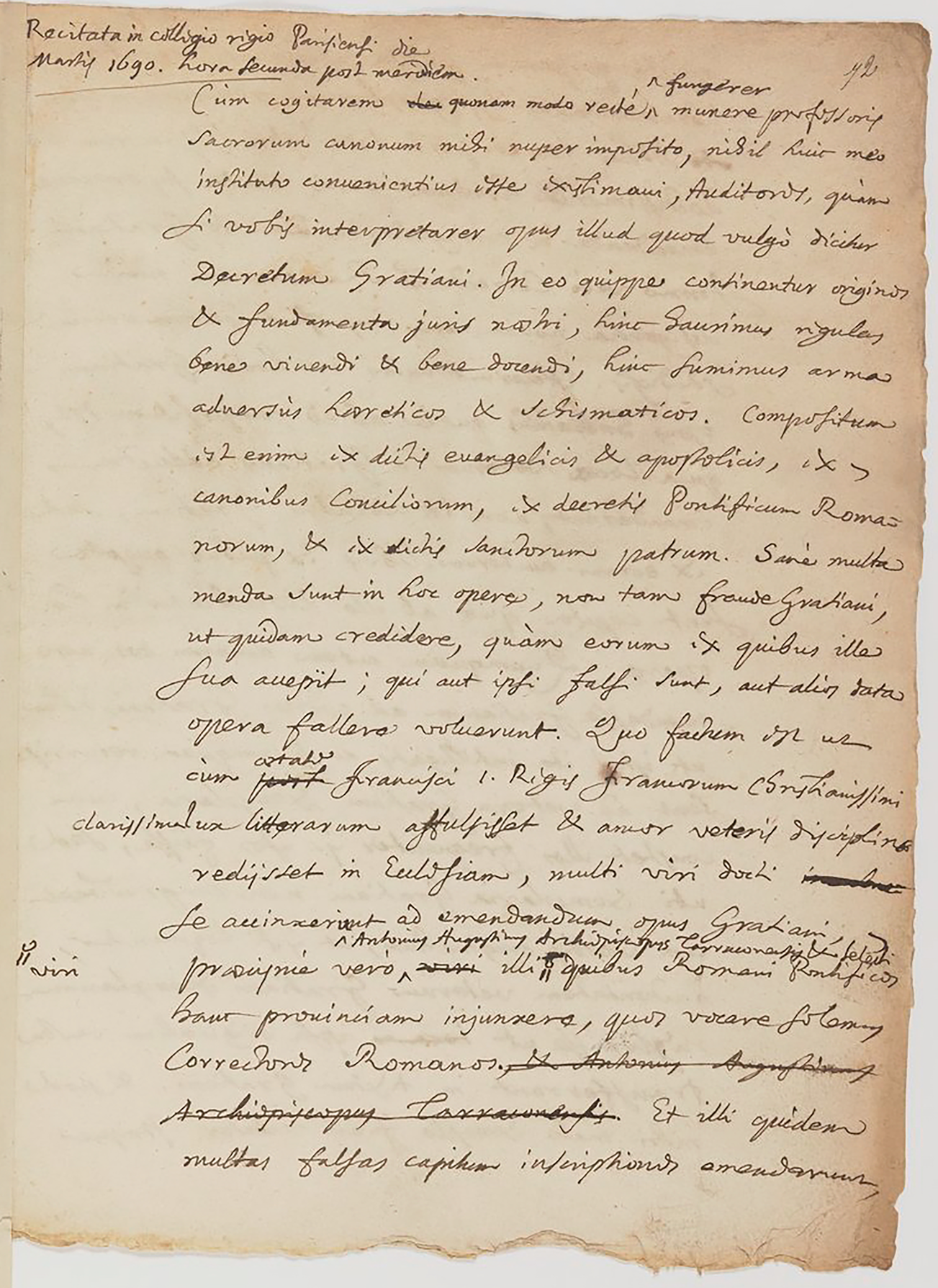

When humanists began to apply new critical tools to ecclesiastical traditions in the fifteenth century, they turned their attention to Gratian. It was not until the mid-sixteenth century, however, that jurists and philologists, largely prompted by the Protestant challenge, attempted a comprehensive revision of the Decretum. Baluze lectured about two important projects: “Many learned men dedicated themselves to the emendation of Gratian's work, and especially Antonio Agustín, the archbishop of Tarragona, and the group which the Roman popes chose and charged with the task, whom we customarily call the Roman Correctors. These men emended many spurious rubrics, removed many which were placed incorrectly, and removed copyists’ and printers’ errors. Yet, despite all of the efforts on the part of these very hard-working and very learned scholars, much remains to be emended and corrected in Gratian's Decretum.”Footnote 6 The latter work which Baluze referred to was the 1582 Roman editio typica (typical edition), the first official Catholic edition of the Decretum (fig. 1). It was a landmark of Tridentine scholarship prepared by a group of scholars and theologians at the orders of the popes in the aftermath of the Council of Trent (1545–63). Baluze chose to juxtapose it with the work of Antonio Agustín (1517–86), Spanish bishop and savant, whose extensive treatise on Gratian's Decretum, De Emendatione Gratiani Dialogorum Libri Duo (Two books of dialogues about the emendation of Gratian), had enjoyed wide recognition since it was first published in 1587 in Tarragona (fig. 2).Footnote 7

Figure 1. Title page of the official Gregorian edition of the Decretum Gratiani. Rome, 1582. Young Research Library, Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles. Public domain.

Figure 2. Title page of Antonio Agustín, De Emendatione Gratiani. Tarragona, 1587. Biblioteca Patrimonial Digital de la Universitat de Barcelona, Fons Antic, 07 XVI-685. Public domain.

This article focuses on Agustín's De Emendatione, his relationship with the landmark Roman project, and more broadly, humanists’ approaches to canon law in the sixteenth century. My essay shows how Agustín, correcting the text of canon law, navigated between his own scholarly integrity and the confessional requirements of the Tridentine reforms. I examine how a classically trained humanist applied his refined critical skills, originally honed on ancient topics, to advance the urgent cause of the Church. I thus shed additional light on the extent to which humanistic scholarship concurred with the Counter-Reformation agenda. The ambiguous attitude of the Catholic hierarchy toward the Decretum is a crucial, and overlooked, aspect of the history of early modern Catholicism. Agustín played a pivotal role in the contemporary study and reshaping of canon law, and his contribution to the religious and intellectual history of early modern Europe deserves more attention.

Furthermore, the recently flourishing histories of humanities, including the confessional humanities of the second half of the sixteenth century, and studies dedicated to the production of knowledge have largely neglected canon law as a separate discipline.Footnote 8 The article's focus on canon law uncovers hitherto omitted connections between Renaissance philology and ecclesiastical scholarship. It allows for a new perspective on the entanglement of humanism and religion, confessional conflicts and erudition. Appreciation of the sophisticated ways in which canon law was scrutinized in the confessional polemics allows us to revise further the traditional narrative about the secular development of the modern critical method. This article upholds the view that post-Reformation confessionalization shaped the humanities in a decisive way, rather than hindering their development.Footnote 9 Finally, it corrects the geography of that older narrative by assigning a crucial role in the innovative study of canon law to Iberian scholars, who often have been discounted in the debates on law, scholarship, and humanistic erudition throughout the sixteenth century.Footnote 10

To understand Agustín's scholarship on Gratian, it is necessary to adopt the parachutist's rather than the truffle hunter's perspective. After a biographical introduction, this article presents a sketch of the humanist approaches to the Decretum after Nicholas of Cusa (1401–64) first expressed doubts concerning the text in the mid-fifteenth century; then it looks at the sixteenth-century printed editions, including the 1582 Roman editio typica, the new, official Catholic version of canon law. I argue that Agustín's De Emendatione is best considered as a companion volume to the regulatory work of the Roman Correctors at the Curia, rather than as an effort to compete with the official version by offering a critical revision, as has sometimes been suggested.Footnote 11 I follow the surviving exchanges between Agustín, the Correctors, and Pope Gregory XIII to show their friendly relationships and demonstrate the collaborative nature of their respective projects. The last section of the article lays out the genera errorum, typology of errors, that Agustín identified in Gratian's Decretum, and offers an analysis of his approach to the contested sources of canon law. Throughout the article, I show what Agustín saw as necessary, desirable, and possible in the emendation of the Decretum.

Canon law carried prestigious as well as pragmatic significance in early modern Europe. It permeated Christian society, affecting everyday life and juridical practice by providing a set of detailed moral and disciplinary rules governing relationships between institutions and people, both clergy and lay. Furthermore, canon law was a textual representation of the Church's history—Étienne Baluze invited his students to engage in the course on canon law as “an excursion through the attractive expanses of ecclesiastical history”—and thus commanded authority over traditions.Footnote 12 Its contents could prove critical for upholding, or exploding, confessional ideas about the continuity of ecclesiastical institutions and practices. In other words, canon law mattered, because it contained much of the source material pertinent to early modern religious polemics. Consequently, reviewing Gratian's Decretum demanded a profound critical judgment of the textual sources of ecclesiastical history. These included the history of the papacy, a contentious branch of ecclesiastical historiography, whose Catholic practitioners were subject to particularly stringent requirements of orthodoxy.Footnote 13

Canon law was a key controversial field in confessional debates. Yet its tortuous history posed a challenge within Catholic orthodoxy itself. Tridentine scholars trying to prove the thesis often summarized as semper eadem, always the same, constantly crashed against Gratian's Decretum, whose confused genealogy, composition, and contents very clearly demonstrated the instability of the Church's traditions.Footnote 14 The tense situation Agustín found himself in, caught between the rigorous rules of textual criticism and renewed Catholic orthodoxy, was hardly unique. He most evidently resembles the subjects of Stefania Tutino's study of the troublesome relationship between language and truth in Tridentine Europe.Footnote 15 Observed from a similar perspective, Agustín appears to have steered a course between various kinds of authority—that of the philologist, the historian, and the theologian—much as Cesare Baronio (1538–1607) did when preparing the monumental Annales Ecclesiastici (Ecclesiastical annals, 1588–1607).Footnote 16 Tutino's Baronio ultimately proved to be first a theologian, and only then a historian, eager to bend the laws of scholarship in favor of the religious truth. A more critical approach was adopted by Agustín's friend and collaborator, the Augustinian monk Onofrio Panvinio (1529–68), in his work on papal history.Footnote 17 Panvinio's relationship with truth, at least when writing ecclesiastical history, was less troubled than Baronio's and attracted the Roman censors’ attention. Still, they both contributed to the same project of writing the Church's history and traditions anew.

Agustín's work on canon law had similarly far-reaching consequences for contemporary Catholic claims, yet historians have almost exclusively, and anachronistically, cast him as a philologist and antiquarian dedicated to secular ancient topics and Roman law.Footnote 18 Barring isolated studies, his work on ecclesiastical topics remains largely unexamined. Agustín's works on canon law have mostly attracted the attention of canonists practicing their discipline in specialized journals.Footnote 19 De Emendatione thus stands out as Agustín's least-studied work, which ironically reflects his own contemporary concern that the precise study of canon law had not been duly appreciated: “[A.] You will not find many who have dedicated themselves to this kind of study. B. Does that surprise you? There are no rewards in it, as there are for practicing lawyers. Honor feeds the arts, as they say.”Footnote 20 This article attempts to restore an important dimension of Agustín's body of work and demonstrate his commitment to the Catholic confessional agenda.

WHO WAS ANTONIO AGUSTÍN?

Born in 1517 to a prominent Aragonese family, Agustín began his intellectual formation at Alcalá and Salamanca.Footnote 21 In 1535, he left for Bologna and Padua, where he graduated as a doctor utriusque juris, a doctor of both laws—canon and civil. His scholarly debut, Emendationes et Opiniones (Emendations and opinions, 1543), a philological and historical commentary on the Florentine Pandects, earned him recognition and consequently an appointment as one of the two Spanish auditors at the Sacra Rota, the Church's highest court, in 1545.Footnote 22 While in Rome, he led a circle of innovative antiquarians and philologists gathered around the Farnese family and prepared editions of Varro (116–27 BC) and Festus (later second century).Footnote 23 In 1555 and 1558, he undertook papal diplomatic missions, respectively, to England and Vienna, and in 1559, he went to Sicily as a royal visitor. Agustín had always hoped for a civil appointment in his native Aragon to follow in the footsteps of his father.Footnote 24 When this did not happen, he accepted the bishopric of Alife (in the Kingdom of Naples, then forming part of the Crown of Aragon). He was ordained as a priest and consecrated as a bishop within the space of three days in December 1557. In 1561, he was appointed to Lérida, where he arrived three years later, after participating in the last period of the Council of Trent (from 1562 to 1563). In 1576, he was promoted to the archbishopric of Tarragona. Agustín passed away on 30 May 1586 and was buried in his cathedral in the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament, which he had commissioned a few years earlier (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Eighteenth-century portrait of Antonio Agustín prepared by Juan Bernabé Palomino and printed by Juan de Zúñiga. Image from the collections of the Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid. IH/106/8.

Agustín would repeatedly complain that the work at the Curia interfered with his scholarship. Nevertheless, he managed to sustain his many interests during even his busiest times in the service of popes and Spanish kings. Unlike many contemporary Catholic scholars in Tridentine Europe, Agustín never stopped pursuing his secular antiquarian agenda, despite his work as a cleric. Disagreement over the compatibility of these pursuits led to a temporary estrangement from his close friend Latino Latini.Footnote 25 At the same time however, Agustín would follow another friend's advice and present his most famous work, Diálogos de medallas, inscriciones y otras antigüedades (Dialogues on coins, inscriptions, and other antiquities)—an erudite technical treatise on numismatics and epigraphy—as if it was written in Rome before he became bishop, to avoid criticism and confusion.Footnote 26

Agustín's episcopal career awaits satisfying analysis. The present article cannot do justice to the topic. It is important, however, to keep in mind that his pastoral dimension as well as scholarly interests motivated his work on canon law. On the one hand, Agustín never concealed his preference for civil service (appointments at the Roman Rota could also be secular). On the other hand, once ordained and consecrated, he displayed exemplary dedication to the shaping and promotion of the Tridentine agenda and his pastoral duties. He ranked among the most prominent Iberian delegates in Trent and became a major conciliar standard bearer in Tridentine Spain. Historians have studied other sixteenth-century bishops who combined erudite humanist interests with pastoral duties, most notably Carlo Borromeo (1538–84), his cousin Federico (1564–1631), Gabriele Paleotti (1522–97), and the Anglican Matthew Parker (1504–75).Footnote 27 Agustín resembled them in important ways, related to the governance of his dioceses and his advocacy for the universalizing Tridentine regime. Nevertheless, he belonged to a particular Spanish order of Catholicism. He grew up immersed in the reformative ideas at Alcalá, which had been founded by cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros (1436–1517) to provide Spain with a new kind of clergy: educated, disciplined, and loyal to the Crown (Spanish rulers traditionally depended on higher clergy for governing the state).Footnote 28

HUMANISTS AND GRATIAN'S DECRETUM BEFORE AGUSTÍN AND THE ROMAN CORRECTORS

Emendation of Gratian's Decretum posed a unique combination of challenges, calling for expertise in law, philology, and theology. The compilation was not entirely original, as Gratian drew heavily from earlier work by Burchard of Worms (ca. 965–1025) and Ivo of Chartres (ca. 1040–1115), but the Decretum distinguished itself from the previous collections by its comprehensiveness, even at the price of including opposing statements. Gratian titled his work Concordia discordantium canonum (Concordance of discordant canons) never trying to camouflage the conflicts in its contents. Gratian's later notoriety also resulted from the Decretum's inclusion of material from highly contested collections, such as the one compiled by Pseudo-Isidore.Footnote 29 Two fundamental obstacles thus stood between the critic of the Decretum and success. First, Gratian's work from the beginning was a Gordian knot of legal and ecclesiastical traditions. Second, for centuries scribes, editors, and reformers had entangled the text with extra strands of confusion and commentary. The eventual emendation required untangling the entire knot, not just its initial weave.

The Decretum was divided thematically, rather than chronologically, into three parts: Distinctiones (about the general rules of canon law and clergy), Causae (administrative matters and issues related to marriage), and De Consecratione (devoted mostly to sacraments). Throughout the Decretum, quaestiones introduced legal problems, to which Gratian provided explanations excerpted from sources. The former were considered canons, whereas Gratian's own remarks were known as dicta Gratiani, Gratian's sayings. Gratian meant the Decretum only for pedagogical purposes, but it quickly became recognized as the prevailing code of Church law and was applied by lawyers in practice, despite lacking any definite stamp of approval from Church authorities. It underwent periodic revisions, most famously in the 1230s by the Catalan Dominican Raymond of Penyafort (ca. 1175–1275), who also edited Pope Gregory IX's new decretals, which often contradicted earlier texts, into a new book of the Decretum. On this occasion, Gregory ruled to abrogate prior redactions of canon law in the first attempt to regularize the Decretum.Footnote 30

Despite the unequivocal attractiveness of the Decretum as a philological and historical challenge, the giants of Renaissance philology and philosophy did not study canon law systematically. Lorenzo Valla (ca. 1407–57) remained condescending toward canon law because to him it appeared “too Gothic.”Footnote 31 Valla mocked Gratian and other medieval canonists for being merely compilers rather than authors.Footnote 32 The original defects of canon law for Valla were a matter of style and erudition. This objection was dwarfed, however, by the question of the authenticity of its contents. Among the most outstanding early supplements to Gratian's Decretum was a text of the so-called Donation of Constantine (Constitutum Constantini), a document based on an elaborate legend describing how Emperor Constantine rewarded Pope Silvester (d. 335) with the Western part of the Roman Empire as thanks for the miraculous healing of his leprosy. The Donation—largely believed to be a late eighth-century forgery created in the papal chancery to boost the Church's political authorityFootnote 33—became a key and contentious part of canon law compilations. Valla famously attacked the Donation with his De Falso Credita et Ementita Donatione Constantini (On the falsely believed and forged donation of Constantine, 1440),Footnote 34 but it had already been flagged in the early fifteenth century by the German theologian and reformer Nicholas of Cusa. Cusa fulminated against its spurious and apocryphal nature, as he could not find a single mention of it in contemporary sources.Footnote 35 Valla criticized the legitimacy of Constantine's gift as well as the linguistic and factual anachronisms in the traditional text of the Donation. His rhetorically sophisticated attack was precise, but his work did not spearhead a revolution in scholarly approaches to ecclesiastical legal traditions.Footnote 36 Valla was also working for King Alfonso of Aragon who argued with the pope over Naples, and his work thus reflected contemporary politics rather than an attempt at the systematic revision of the Church's legal corpus.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Erasmus (1466–1536) added fuel to the fire. Erasmus was an avid reader and promotor of Valla's Elegantiae Linguae Latinae (Elegances of the Latin language, 1471). He also edited and published the manuscript of Valla's annotations on the New Testament and used it as the basis of his own scriptural commentary.Footnote 37 Unsurprisingly, Erasmus similarly lacked enthusiasm for canon law, and his feelings toward its scholastic practitioners ranged from rejection to contempt. As Erasmus wrote to Noël Béda (ca. 1470–1537), the relentless theology professor who eventually led the University of Paris to condemn Erasmus in 1528, he “has always kept away [from their teachings] as much as possible.”Footnote 38 Unlike Valla, who made the effort to dismantle a single document from the inside, Erasmus interrogated Gratian and the scholastic tradition holistically. He was simultaneously worried by the incongruity of the composition and by the dubious status of its authority. Erasmus questioned the very provenance of the Decretum. He attacked its author's identity too, mockingly calling him “Gratian or Crassian,” and reprimanded him for his unclear quotation practices and negligence in critically assessing sources. Gratian was measured against Jerome, Erasmus's paragon of scholarly integrity: “Gratian at that time was not discussing the authorship of the books he cites, whether Jerome's or another's. Rather he mustered into his final line of argument evidence that seemed to confirm the case he was making. And since it is customary for jurists to cite by author's name, he added the name he found by chance in the manuscript. Similarly, Saint Jerome, too, cited the Rhetorica ad Herennium as Cicero's. Yet if a dispute had arisen about this attribution, without doubt Jerome would have denied such a provenance for the work.”Footnote 39 In this competition, Gratian and Jerome represent, respectively, deficient scholasticism and real scholarship. Gratian's sloppiness with sources disturbed Erasmus, for “purging the spurious . . . was central to Erasmus’ sense of his calling as a Christian scholar.”Footnote 40 In his work on Jerome, Erasmus put much effort into portraying medieval ecclesiastical scholarship as a quagmire of forgeries and misattributions.

Erasmus was not the only well-known reader of Valla in the sixteenth century. Early in 1520, Martin Luther (1483–1546) was given a copy of On the Donation. Valla's critique of the legal foundations of Rome's authority further convinced Luther that the pope was the Antichrist and contributed to his rejection of canon law as such.Footnote 41 Luther saw the connection between the papacy and canon law as absolute and believed that denouncing one would automatically entail the fall of the other. Scholars have also argued that Luther's contempt for canon law had its origin in his theology and idiosyncratic understanding of divine justice.Footnote 42 Consequently, Luther was not interested in the emendation or reformation of canon law but in its elimination, which was a step further than Valla or Erasmus took. Luther's continuing attack on papal authority eventually gave impetus to the critique of canon law by the Magdeburg Centuriators, whose efforts produced a massive Ecclesiastica Historia (Ecclesiastical history, 1559–74)—the essence of the learned Protestant assault on the Catholic interpretation of history. They attacked with particular fervor the authenticity of texts ascribed to early authorities, the Apostolic Canons, and the False Decretals from the Pseudo-Isidorian corpus. Their arguments were much more focused than Luther's general rage, since the Centuriators employed state-of-the-art humanistic critical tools that pointed to internal contradictions, stylistic deficiencies, and inaccurate citations in the texts.Footnote 43

Valla, Erasmus, and Luther preferred to reject Gratian altogether, rather than focus on individual passages or philological minutiae in the Decretum. Their work cast a shadow on the whole edifice of canon law. They did not recognize the circumstances under which Gratian worked. Once critics learned more about how the collection had been compiled, they judged it more leniently. Their critique did not encourage work on the text. This was achieved more successfully by the Centuriators, whose denunciation of canon law made its study and defense urgent for Catholic scholars. Valla, Erasmus, and Luther also tended to pick the low-hanging fruit, attacking fragments like the Donation of Constantine that were already known to be problematic but essentially peripheral to the Decretum. Medieval canonists had already recognized constant changes in canon law and discordances in the Decretum, as well as Gratian's sloppy transmission of quotations. Valla's, Erasmus's, or Luther's critiques were not always sophisticated, but it was the unrivaled circulation of their ideas that catalyzed the following generation of humanist responses.

The heightened interest in Gratian after the Council of Trent was preceded by an intense publishing effort. The Decretum began to come off the presses in the 1470s. It was printed across Europe. Before 1500, a few dozen editions were available, but soon after the turn of the century, France took the lead. Between 1505 and 1570, at least twenty-six editions came out in Paris and Lyon.Footnote 44 Early printed versions to a large degree reproduced the available manuscript material, including the page layout, and hardly reflected the humanists’ text-critical achievements. Editions evolved, however, as scholars became more aware of the variants of the text and began applying advanced tools to Gratian's compilation.

The first attempt at innovation, which left a mark on all subsequent editions, was prepared by the Parisian editor and printer Jean Chappuis (d. 1531). His Decretum Aureum Domini Gratiani (Gratian's golden decree, 1500) visually resembled the source manuscripts. The book was set in a Gothic font, the main text surrounded by glossators’ commentary. The book clearly looked back rather than forward. Still, Chappuis decided to integrate short summaries of the texts referenced in the commentary directly into the gloss, and he added to the apparatus passages explaining episodes from biblical history, providing thus an original commentary on the Decretum himself. Chappuis continued the work of earlier compilers, but his contributions were remarkable enough to be adopted by almost all subsequent editors.Footnote 45

In 1547, Antoine de Mouchy (Demochares, 1494–1574) published a milestone edition of the Decretum. De Mouchy's Decretorum Collectanea (Book of collected decrees) was the first modern critical presentation of Gratian's work, featuring fresh marginal paratitla (summaries) of the core parts and novel indexes inviting different ways to study the text. De Mouchy also omitted the traditional gloss. In the established curriculum, the commentary always framed the text and made it accessible by providing explanations of terms and customary interpretations. From the practical, legal standpoint, Gratian's Decretum did not make much sense without the layers of commentary, but abandoning the gloss encouraged a focused study of the core text. In the margins, De Mouchy indicated the sources from which Gratian derived individual passages and gave precise references to their titles, books, and chapter numbers, so that the reader could easily identify the sources in their original context and correct the Decretum, should any distortion emerge.Footnote 46 De Mouchy's edition was reprinted a decade later by Antoine Le Conte (Contius, ca. 1525–86), first in Paris (1557), then in Antwerp (1570).

Between the two editions of De Mouchy's Collectanea, the French jurist Charles Du Moulin (Molinaeus, 1500–66) presented his own take on Gratian.Footnote 47 His chief editorial contribution consisted in renumbering the canons. The system stood the test of time and was still employed in the twentieth century.Footnote 48 Du Moulin also corrected many scribal errors in the Decretum, relying on his iudicium, scholarly ingenuity. It was Du Moulin's commentary on the Decretum, however, which made his work significant in sixteenth-century religious controversies. He differed from other contemporary French editors of Gratian in that he was a practicing lawyer. Regular contact with the application of law prevented him from taking an overly doctrinal approach to legal texts, whether in civil or canon law. Du Moulin's versatile humanist education also helped him develop a better sense of the historicity of law.Footnote 49 He understood that legal texts had always been influenced by circumstances, and that law had always been changeable. Hence, he explicitly criticized a number of source texts in the canon law corpus. As a reader of Valla, he repeated the critique of the Donation of Constantine. He also followed Erasmus in identifying spurious fragments from Ambrose and Augustine. More important still, he cast doubts on the genuineness of many papal decretals and the Canons of the Apostles,Footnote 50 which directly impugned Rome's privileges.Footnote 51 Throughout his life, Du Moulin vacillated between Catholicism and Calvinism, but his annotated edition was above all a Gallican summa of distrust toward the textual support of papal traditions.Footnote 52 The book was swiftly put on the index, but it paved the way for Baluze and his contemporaries in the seventeenth century.Footnote 53

Emendation of Gratian could mean different things, as agendas behind respective projects differed and shifted. But ultimately, the concerted efforts of humanists in the sixteenth century aimed to establish the correct text of the Decretum. The French editions prepared by Chappuis, De Mouchy, Du Moulin, and Le Conte had numerous flaws, and the eventual Gregorian edition, which fixed the text of the Decretum for the Catholic world, overshadowed all previous attempts to correct Gratian's work. Despite the Gallican controversy, the scholarship on Gratian in the 1570s and 1580s grew organically from the vibrant French editorial enterprise of the previous decades. The Roman Correctors and Agustín worked in a tradition that had just undergone major renewal.

Scholarship on Gratian that focused on establishing the text mirrored the humanists’ continuous work on ancient literature. It was connected to the sweeping contemporary efforts to systematize all sorts of texts and collect and interpret fragments of lost works that they cited. Secular Roman law had already attracted intense scholarly scrutiny. Poliziano (1454–94) had examined the Digest (or the Pandects) manuscript in Florence, and Alciato (1492–1550) and Guillaume Budé (1467–1540) had commented on the text extensively.Footnote 54 In 1529 Nuremberg, Gregor Haloander (1501–31) published the first critical edition of Justinian's Corpus Iuris.Footnote 55 His edition was faulty—as Agustín showed in Emendationes et Opiniones—but it catalyzed the process of recovering and publishing corrected readings of legal corpora. Lelio Torelli (1498–1576), the secretary of the Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–74), worked together with Agustín and Jean Matal (ca. 1517–97) on the text of the Pandects, and their editio typica appeared in 1553 Florence.Footnote 56 Torelli and Agustín would always underscore the use of the manuscript in their work, whereas Haloander never even saw the Florentine treasure.Footnote 57 The availability of the revised editions of Justinian's Corpus—and especially the new text of the Pandects—sparked new scholarship both on the text and on Roman law in general. Similarly, the new way of emending and presenting the Corpus Iuris Canonici signaled a change in perceptions of canon law itself.

New attitudes demonstrated humanists’ fresh appreciation of the philological and historical dimensions of canon law. This led them to take further interest in the canonical collections prior to the Decretum.Footnote 58 Agustín was again a key figure in the recovery and reshaping of the original legal texts. In 1576, he published Antiquae Collectiones Decretalium (Collections of ancient decretals), the first comprehensive edition of the early compilations of papal decretals.Footnote 59 The volume drew on Agustín's collecting zeal, as he had been seeking to collate manuscript sources for early canon law and conciliar traditions since the 1540s.Footnote 60 In 1573, he wrote to Pope Gregory that he had amassed a whole library for the purpose.Footnote 61 Diligence paid to the pre-Gratian collections sharpened Agustín's awareness of older and largely forgotten texts, which would prove invaluable in his work on the Decretum. The core of Agustín's scholarship often lay in drawing up skillful operations on textual genealogies—he had already done the same for the manuscript tradition of the Digest in Emendationes, proving that Poliziano's understanding of its transmission was incomplete. The emphasis on the ancient collections as foundations of the Decretum, and on underscoring the organic development of canon law, was sustained by Baluze. In the Parisian lecture, he clarified: “Before I undertake the topic, I will offer you a discussion of the old collections of canon law before Gratian, so that you do not approach these studies unprepared.”Footnote 62

AGUSTÍN AND THE ROMAN CORRECTORS

The history of the official Roman edition began soon after the conclusion of Trent. The council did not treat canon law separately, but the post-conciliar drive toward universalization of ecclesiastical practices required the Church's law to be subjected to a new redaction. It corresponded with similar initiatives to recover, renew, and systematize liturgical and prayer books. The combined effort intended to reaffirm confessional authority over tradition, while simultaneously purging the texts from as many errors as scholarly and theologically possible. The period brought forward the revised Breviary and Vulgate Bible, as well as a series of official Catholic editions of councils, decretals, and canon law.Footnote 63

The project to renew Gratian's Decretum was originally conceived by Pius IV (d. 1565), but it started only under his namesake successor in 1566. Gregory XIII (r. 1572–85), who had previously distinguished himself as a jurist, took over from Pius V (r. 1566–72). He was predestined to guide the work to its completion. The two popes set up a commission of learned cardinals (for the most part) who supervised the work of a larger group of scholars and theologians. There were about twenty Correctors working on the Decretum at any given moment in Rome, with prominent figures such as Gabriele Paleotti (1522–97), Guglielmo Sirleto (1514–85), Francesco Alciati (1522–80), and Ugo Boncompagni (later Gregory XIII) forming the core of the original congregation. The project extended far beyond the city, however, as the committee constantly sought help and information from Catholic scholars scattered around Europe.Footnote 64 The correspondence reveals a shared sense of urgency about the project to edit the Decretum anew, as scholars reaffirmed their dedication to emending canon law in order to “protect the integrity of the Catholic faith,” “reform the corrupted morals of the present time,” and “renew the discipline.” The Correctors and their correspondents used a variety of terms to describe the operations performed on Gratian's Decretum, such as “restoring from the sources” (restituere ex fontibus), “emending” (emendare), “correcting” (corrigere), and “cleansing” (repurgare), which matched the vocabulary used in the Tridentine conciliar debates on the Bible.Footnote 65

The work of the papal commission concluded with the publication of the editio typica in 1582. Two years earlier, Pope Gregory XIII had promulgated the bull Cum Pro Munere, which formally gave the Decretum, together with the decretals and the accompanying glosses, the title Corpus Iuris Canonici, mirroring the secular Roman law. The bull forbade the use of other versions of the text and reserved publishing privileges to the Holy See.Footnote 66 In addition, the Roman commission published a volume of ius novum (canon law written and collected after Gratian), which contained an approved version of Gregory IX's decretals.Footnote 67 The Roman edition abandoned the original title of Gratian's compilation, as the Correctors decided on the simple Decretum Gratiani, in the teeth of the overwhelming evidence of the manuscript tradition.Footnote 68

Mary Sommar argued that the decision of the pope and the Curia to claim exclusive authority over the official Roman edition prevented Agustín from taking part in the work in person, since it would have required him to make difficult intellectual compromises. Remaining outside, by contrast, allowed him to write De Emendatione, which offered “a good humanist critique of the textual problems without unduly arousing the enmity of the Roman conservatives.”Footnote 69 This assessment appears reasonable, yet it rests less on historical evidence than on the traditional portrait of Agustín as a strict humanist reluctant to serve the Church's agenda at the expense of his scholarly integrity. It is tempting to see the Roman editio typica and Agustín's De Emendatione as opposing each other: one, a work of Catholic institutional propaganda, and the other, a sophisticated scholarly analysis of the Decretum and its flaws. This sharp distinction, however, defies contemporary categories. Agustín and at least some of the Roman Correctors regarded both attitudes as natural and compatible. It is more helpful to see both works as complementary. Agustín would, in fact, explicitly mock the suggestion that he should edit a canonical collection of his own instead of emending Gratian's errors: “as for your urging that I should edit a collection rather than fix this troubled and imperfect one: I told you, you must be joking.”Footnote 70 Agustín expressed limited disappointment regarding the editio typica, but he never worked against it. Any hesitance to engage in work on site in Rome should be credited to his personal circumstances. Agustín, who had traveled widely in earlier years, never left Spain again after he came back in 1564 to lead the bishopric of Lérida. Health problems, family matters, and pastoral commitments in Catalonia prevented him from returning to Italy. He would even turn down Gregory XIII's invitation to join the festivities in Rome on the occasion of the 1575 Jubilee.Footnote 71

Plans to include Agustín in the work of the Roman Correctors’ congregation existed from the first days after its conception. On 20 May 1565, Joan Marsà, one of the secretaries, wrote to Agustín, describing the early progress and the system adopted by the Correctors to achieve editorial efficiency. He informed Agustín about the letters that had been sent to universities around Europe asking for help with a particularly convoluted fragment of the Decretum, and warned that Agustín too should expect to be called upon: “We are in the Fifteenth Distinction, and it has already been two days that we cannot exit from it, because of the great diversity [of the source text]. . . . It will be necessary that Your Excellency also help, as this enterprise can benefit a lot from Your Excellency's studies. Should things go that far, they say that the pope will let you know.”Footnote 72 Marsà emphasized the need for precision too: “It is His Holiness’s intention that things turn out correctly.”Footnote 73 The gaps in the extant correspondence do not let us follow the course of events seamlessly. Contacts between Agustín and the Correctors continued, though, and they certainly picked up steam in the 1570s. When Pius V passed away in 1572, the cardinals elected Ugo Boncompagni as his successor. The new pope, who became Gregory XIII, was indeed an old friend of Agustín's. They had first met in Bologna in the late 1530s, Agustín as a student, the future pope one of his law professors. Agustín also cultivated his friendship with the secretary Miguel Thomás de Taxaquet (1529–78)—in fact his old protegé—and Latino Latini (1513–93) became involved in the project at the same time.Footnote 74

Less than six months into his reign, Pope Gregory wrote to Agustín, recalling his earlier contributions to the project and calling for new assistance with manuscript source texts. He asked most specifically about the early manuscripts of Isidore and the council of Lérida (524).Footnote 75 Agustín had to disappoint the pope regarding the Council of Lérida, but he was slightly more hopeful about Isidore:

When I came back here [to Lérida] I had no more urgent task than to satisfy the demand of Your Holiness, and I employed all my effort and diligence. After that old council, which was in the times of [pope] Symmachus,Footnote 76 Lérida was occupied by the barbaric Saracens for six hundred years, and it kept nothing except for the ancient name of Ilerda. There are no old books [here], save for those which I brought with me, or those that I arranged to be bought. Other [books], which I saw here, or I heard that they are here, are no more than two hundred years old. I know that in Zaragoza there is the most ancient volume of Isidore's Etymologiae: it is believed to have been sent to Braulio, the bishop of Caesaraugusta [Zaragoza], by Saint Isidore himself.Footnote 77

The authority of the famous exemplar of Isidore rested both on its antiquity and the belief about its provenance directly from the author. In his work with canon law sources, Agustín emphasized the library research necessary to uncover the oldest available versions of the texts. Following the humanist philological tradition, he assumed that textual sources developed more errors as new copies were made and believed that the oldest surviving manuscripts were the least corrupted. Writing to Pedro Chacón (1526–81), his fellow Spaniard and also one of the Correctors, about the progress of his work on the oldest decretals, Agustín similarly mentioned that he would grant more authority to the first collection because “the other decretals, with few exceptions . . . irritate with their stories and allegations. The first compiler appears to be more like those who wrote the decrees, for there are more texts [there] from the councils, the Sacred Scripture, Saint Gregory, and other saints.”Footnote 78 This verdict rested on decades of experience handling manuscripts, which gave Agustín a deep sense of texts’ changeability, and it spoke to Poliziano's genealogical approach, which on principle accepted older material as more trustworthy.Footnote 79

Agustín's generous reply to Gregory XIII's letter did not elicit much response, except for a couple of thank-you notes penned by Cardinal Alessandrino (Michele Bonelli, 1541–98).Footnote 80 Agustín lamented to Chacón that he was not being consulted more often: “From the very beginning I asked them to ask for what they lack or what they have doubts about, and I have seen only one list, where they once asked about various authors and conciliar and papal decrees.”Footnote 81 He kept on seeking editorial news as he eagerly anticipated the publication of the editio typica.Footnote 82 But his enthusiasm for the Roman Correctors’ work never made him neglect his own project to emend the Decretum. As he was feeding manuscripts and advice to his friends in Rome, his own treatise on Gratian slowly materialized.

THE “FOREST OF ERRORS” AND PHILOLOGICAL EMENDATION

When Étienne Baluze praised Agustín's work in front of his audience, it was not a rhetorical device or an erudite stunt. Baluze knew De Emendatione intimately, as he prepared an annotated reissue of it.Footnote 83 Agustín's treatise was considered essential for the education of Gallican scholars in seventeenth-century France, but scarce in her libraries.Footnote 84 One of Baluze's closest friends, the famous Benedictine Jean Mabillon (1632–1707), similarly singled out Agustín's work as a foundational reading in ecclesiastical history: “To read the Decretum with benefit and understanding, it is necessary to look at the remarks and corrections made on Gratian by Antonio Agustín.”Footnote 85 Baluze's reedition of De Emendatione appeared in Paris in 1672. The handsome octavo featured an extended critical introduction and almost two hundred pages of new notes, in which Baluze commented on both the Decretum and Agustín's analysis. He dismissed more than a few of Agustín's interpretations, as the latter's conservative and Rome-centered views conflicted with the Gallican perspective, but the Parisian reedition bears witness to the continuing relevance of Agustín's study. Baluze, pursuing an agenda distinct from Agustín in Rome and Spain a century earlier, gave De Emendatione a new meaning in another context. At the same time, he exposed the confessional constraints which affected its author. Baluze's remarks castigating Agustín's conservatism caught the attention of the Roman censors, who recommended that the book be placed on the Index because of its apparatus.Footnote 86

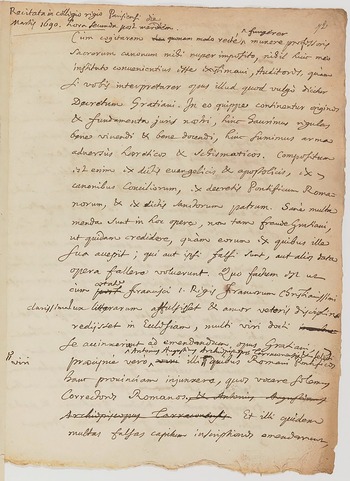

Some of Agustín's interpretations dated over the next century. But the whole work appealed to French scholars, especially the Maurists gathered around the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in the late seventeenth century, as a treatise on method that remained exemplary despite its age. Baluze finished his editorial introduction to De Emendatione by listing all new manuscripts available to him for the further emendation of the Decretum. He would explain that “the specific goal [of my notes] is to indicate the variant readings of the manuscripts and printed codices, in such a way that we follow the method [methodum] which Antonio Agustín observed in his book.”Footnote 87 Classicist Arnaldo Momigliano presented these French scholars at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries simultaneously as leading interpreters of previous scholarship and as cutting-edge innovators. While scholars in Italy were anchored in the past and looked back, the French overtook them: they adopted inter-disciplinary attitudes and favored collaboration in their work; they were once again open to the pagan Greco-Roman tradition; and they liberated themselves from the remains of the scholastic perspective when approaching Church Fathers and ecclesiastical history.Footnote 88 That Agustín's scholarship, born in the Italo-Spanish tradition, was appreciated in France over a hundred years after it first came off the printing press in Tarragona is meaningful.Footnote 89 It was not a slip of the pen, therefore, when in his manuscript notes for the Parisian lecture Baluze rephrased the paragraph about previous attempts to emend the Decretum and put Agustín ahead of the Roman Correctors, suggesting whose achievements mattered most. This change is the only major crossing out and rewording on the four pages of the lecture's text, which otherwise appears to be a finished draft of the presentation. Agustín, in fact, is the only scholar whom Baluze mentioned in his talk by name (fig. 4).Footnote 90

Figure 4. Draft of Baluze's lecture. Bibliothèque Nationale de France/Gallica, Baluze 277, fol. 72r. Public domain.

De Emendatione is a humanistic miscellany, written as didactic dialogues, which explores the nuances of the Decretum's text and establishes rules and norms of emendation. The goal resembles Agustín's early work on the Pandects, whereas the dialogue form parallels that of his contemporary Diálogos de medallas. The treatise stands out among Agustín's works dedicated to the legal traditions of the Church, as it does not provide the reader with an edition or a reconstruction of a source text. De Emendatione draws heavily from the tradition of humanist philological texts like Valla's Elegantiae (1471) and Poliziano's Miscellanea (Miscellanies, 1489), despite adopting a radically different narrative genre. It also owes something to Andrea Alciato's Parergōn Iuris (Parergon of the law), which explored the Roman Digest in a similar manner, curious case by curious case.Footnote 91 De Emendatione thus connected philology, law, and theology in a novel way.

Careful reading of Agustín's treatise reveals rarely appreciated connections between his Roman and canon law studies. This in turn allows for the correction of the unfortunate segregation of civil and canon law studies in the historiography of early modern scholarship. Analysis of the studies on Gratian's Decretum demands situating them in the context of the practices related to the civil law, because Renaissance humanists never saw them as disconnected.Footnote 92 The new criticism applied to Gratian employed the same tools that humanists first honed working on Roman law. Agustín's advantage over most contemporary canonists originated in his extraordinary fluency in the Roman civil code. Du Moulin, notwithstanding his volatile confessional allegiances, similarly distinguished himself as a Roman lawyer before he approached canon law.

Agustín understood his task as bringing canon law back to the sources. Prefacing his edition of the penitential canons, he explained that it was “necessary to go back to the sources, from where [the decrees of the popes and councils] flowed, so that we distinguish the certain from the uncertain.”Footnote 93 In his approach, Agustín echoed his Complutensian alma mater's call to return ad fontes, which permeated contemporary biblical scholarship and similarly fueled Tridentine arguments on Scripture. He would liken the philological process around Gratian to the “restitution of the limbs forcefully severed from the body.”Footnote 94

The transformation in the study of canon law, for which Agustín was largely responsible, consisted thus in its historicization.Footnote 95 A similar change in the mode of analysis, “from philosophical towards more philological-historical—or ‘humanist,’” impacted contemporary theology. Each case describes a central concern of confessional scholarship, and they both demonstrate that religiously engaged studies accelerated, rather than impeded, the advancement of humanistic critical methods in the sixteenth century.Footnote 96

Agustín knew as well as anyone at the time that all sources should be studied together, whereas scholastics rarely stepped outside of Gratian's text. Much of the Decretum rested on the decisions of Church councils, which were the bedrock of canon law. To connect the petrified rubrics of the Decretum with conciliar history meant furnishing it with a critical institutional context. Agustín built his unmatched expertise on all things conciliar by working on a number of editorial projects, including Epitome Iuris Pontificis Veteris (Epitome of old papal law), a massive repertory of canon law structured as a giant commonplace book.Footnote 97 Agustín learned most about conciliar history, though, by preparing his own edition of universal (ecumenical) councils. Like the Decretum, councils already had an editorial history. Agustín did not think much of the available publications, however, as he castigated the editors for contenting themselves with piecing the councils together from the extracts in canon law, rather than editing them from the originals.Footnote 98 Agustín's own project never materialized. He would keep referring to the ongoing work on “an epitome of the councils . . . divided into common places” in his correspondence, but the project proved a source of continuous frustration.Footnote 99 The failure was surely connected to the editorial challenges related to his insistence on a multivolume bilingual edition, but this was only one side of the coin.Footnote 100

The history of ecumenical councils counted among the most contentious fronts of the Catholic-Protestant fight. As Counter-Reformation Rome asserted increasingly tight control over legal, liturgical, and historical sources of the Church's traditions, Agustín's enterprise was not in step with the Tridentine program, which claimed not only confessional but also strictly institutional authority over the texts. Agustín surely understood the problem, since he further dismissed Laurentius Surius's edition of the councils in De Emendatione by questioning the status of his work: “These are compiled without any public authority. The collector put this together from the Panormia of Ivo and from Gratian, and other books of uncertain titles, out of his private intention to please the readers.”Footnote 101 Agustín's efforts were not in vain, however, as the official edition of the ecumenical councils, which appeared in Rome between 1608 and 1612, drew heavily on his preparatory materials.Footnote 102

In De Emendatione, Agustín displayed his superior knowledge of conciliar and papal chronology to expose anachronisms, emend scribal slips, and correct attributions. Discussing whether Pope Nicholas (ca. 800–67) or Leo (ca. 400–61) attended the first council of Carthage, he would underscore the method explicitly. Agustín instructed his interlocutors: “You cannot understand this, unless you reject the errors in the rubrics, and match Gratian's divagations with the councils and the old collections.”Footnote 103 Agustín also discussed anachronisms in his correspondence with the Correctors: “I will give as an example chapter 3 ‘si quis presbyter a plebe’ etc. from the Council of Lérida, under king Theodoric, around the time of [Pope] Symmachus or Hormisdas . . . How can it be from that council if it mentions the [oath of] purgation of pope Leo, who lived in the times of Charlemagne?”Footnote 104 At the beginning of book 2 in De Emendatione, which focuses on the conciliar sources, Agustín also urged readers to work from unpublished collections of conciliar documents rather than rely on the editions in circulation.Footnote 105 His emphasis on studying canon law together with conciliar traditions was upheld a century later by Jean Mabillon, who taught in his Traité des études monastiques (Treatise on the monastic studies) about the correct ways to approach the subject: “The study of canon law is not very different from that of the councils.”Footnote 106

Agustín was not unlike Valla in providing ferocious criticism of older texts and more recent scholarship. Baluze was convinced that overall Agustín “contended and proved with examples that Gratian was stupid, as he did not notice a great many things.”Footnote 107 In fact, Agustín rarely attacked Gratian himself. He decided against demolishing the building, as Valla tried to bring down the Donation of Constantine, in favor of showing how to renovate it. Conscious of the flaws of Gratian's compilation, Agustín wrote to Pedro Chacón in 1574: “I do not doubt that Gratian's Decretum is imperfect . . . still, he did what he could, like anyone else would, and this was in very barbaric times.”Footnote 108 Agustín had already defended the Decretum in a similar way, by highlighting the historical circumstances of its composition, in the letter to Pope Gregory: “I could augment the Pontifical Law with the Greek books . . . But I have left for another time what Gratian did not think about doing, the fault being the times he lived in.”Footnote 109 He would also excuse Gratian when discussing the references to the councils: “These are not Gratian's errors, but of those times. This is how it is usually presented [edi solitum est] in the councils: Burchard, Ivo, Anselm, and other compilers have it this way.”Footnote 110 When in the text of the Decretum Gratian said “Achor” instead of “Achan” (mistaking the biblical figure, appearing in the Book of Joshua, for the place commemorating his death),Footnote 111 Agustín would defend him, believing it an excusable mistake: “Should this be Gratian's error, it is an error of memory, of the kind that are often found in abundance in Cicero, and other writers.”Footnote 112

De Emendatione is divided into two books of twenty dialogues (chapters) each.Footnote 113 The first book explores the philological and historical deficiencies of the Decretum. The second focuses on conciliar history as foundational for the study of canon law. Agustín opened the treatise with a rebuttal of the Correctors’ innovation regarding the title, because Decretum Gratiani could not be sustained by the manuscript tradition.Footnote 114 Then he lamented the cornucopia of errors in the text. To facilitate following the book, he categorized issues crying for emendation according to the genera errorum, or types of errors, exposing a terrifying variety of problems to his interlocutors:

[C.] What else is there to be changed in Gratian's book apart from the title? A. There is so much that it is not easy to explain everything in one day. But I will lay out for you some of the types of errors, so that later we elaborate on those which appeal to you most. I see that [Gratian] often errs in the names of people, cities, provinces, councils, and other things. . . . The inscriptions are often wrong; those which refer to the councils are misattributed to popes, while those of bishops of lower rank are said to come from either the Roman Pontiff, or a universal or a provincial council. . . . Many words which are attributed to Gregory, Ambrose, Augustine, or Jerome, either do not survive anywhere, or they are by someone else. Others still, which have correct inscriptions, are not referenced accurately. We know that [Gratian] often cites conflicting passages, and often very accurately, [but] in fact, he takes what comes from the Greek sources from different translations, as if they were from different authors; and they often have different meanings in Greek and Latin. C. You are really leading me into a forest of errors, from which I do not see any exit.Footnote 115

The scale of the task made Agustín's other interlocutors briefly despair: “[B.] You confirm me in my old opinion that it is in vain to think about correcting the errors of this author.”Footnote 116 The Decretum exhibited a full range of philological challenges. Mistakes in proper names, wrong attribution of quotations, and discrepancies between Latin and Greek sources piled up as Agustín explored the text, but he clearly hoped to find an exit from this labyrinth. It would not be the first time for him, after all. His work on Gratian was similar to his earlier study of the Pandects. Agustín described in Emendationes how his early work on the Roman law had been sparked by the discovery of a multitude of unsettling contradictions: “Nothing made us more doubtful and uncertain than finding inconsistent text across legal books . . . which disagreed not [just] here or there, but in almost six hundred places.”Footnote 117

Successful emendation of the Decretum depended on the correct diagnosis, so how did the “forest of errors” grow in the first place? Agustín scattered his explanations around the treatise. He denounced copyists for their frequent scribal mistakes, accepting the traditional humanist account of the causes of error. Scribes had always been the chief wrongdoers in the eyes of Boccaccio (1313–75), Salutati (1331–1406), and Valla.Footnote 118 As a humanist lexicographer and antiquarian who had previously edited Varro and Festus, Agustín paid consistent attention to the proper names in the Decretum, even if he knew that it was unrealistic to demand “verborum elegantiam,” elegance of language, from a work with such a complicated history.Footnote 119 In this context, he also criticized Gratian for preserving scribal mistakes by relying on the existing collections rather than studying the sources himself.Footnote 120 Standard humanistic erudition often sufficed to correct these mistakes. To improve the spelling of Ilerda (the ancient name for Agustín's own episcopal city of Lérida), however, Agustín invoked a combination of sources—coins, inscriptions, and verses from Roman literature—in a striking application of new antiquarian skills to textual emendation.Footnote 121 A humanist steeped in the Greco-Roman past and looking at canon law saw things previously hidden from its more traditional students and practitioners.

Scribal mistakes aside, Agustín eagerly castigated professional students of the Decretum, who blindly followed one another and introduced more meaningful errors into the text: “C. What is the cause of so many false rubrics? B. The audacity of some men, and the simplicity and slowness of others. The audacity of those who pretended that some [texts] were authored by someone who had never written them; the simplicity and slowness of those who readily believed that things were the way they read in some other book. One can say they are like the cattle that follow others in their herd, their own eyes tightly closed. Add to this the ignorance and lack of attention of the booksellers, who just like uneducated doctors and pharmacists, readily sell one thing for another.”Footnote 122 Agustín's judgment exhibited a new critical sensibility toward the history of the text, different from scholastic attitudes. The responsibility for the sorry state of the Decretum rested equally with forgers, scribes, and the scholars of the text. The latter's negligence or ignorance cemented the layering of errors over generations.Footnote 123

Dubious orthography could also be corrected by collating Latin with Greek texts. Those mattered most, however, when they offered fuller and purer versions of ecclesiastical traditions. The limited knowledge of Greek in Western Europe prior to the fifteenth century prevented canonists from moving outside the Latin tradition and limited their critical scope. The use of Greek sources made possible a qualitative change in the restoration of the original shape of canon law. Agustín once again pioneered the approach. Speaking about the Council of Sardica (343), he acknowledged the satisfying consistency of the available printed texts, noting however that he was lucky to possess “another very good old Latin edition, more consistent with the Greek.”Footnote 124 He believed that the canons of the council must have been originally composed both in Latin and Greek (modern scholarship has confirmed Agustín's educated guess) and commented to Chacón: “You take from the prologue to Dionysios . . . that the canons of the Council of Sardica were written in Latin, and I believe they were written both in Latin and Greek. . . . One should think that they conformed when they were written. Only then the divergent views of those people [la variedad de aquella gente] made them either hide or change the canons. Photius dared to negate them, even though Pope Nicholas told him that they existed in Latin and Greek.”Footnote 125 Despite the alleged omissions or arbitrary exclusions by the Greeks, Agustín believed an earlier Latin version resembling the Greek promised to be more accurate. Likewise, he indicated that a Greek account of the Third Council of Constantinople (680–81, counted as the Sixth Ecumenical Council) was more complete, and could clarify the disputed liturgical rules regarding deacons: “The Greeks indeed have a seventh chapter in more complete form than Gratian or Ivo, who incorrectly refers to it as if from chapter seven of the seventh council. A deacon should not sit down before the presbyter, unless he would be of the rank of a Patriarch or a Metropolitan.”Footnote 126

Agustín's respect for Greek sources is visible throughout De Emendatione, nowhere more explicitly than in the passages dedicated to the Councils of Braga (561 and 572), as related by Saint Martin (Martinus Bracarensis). Agustín reassured readers not only that it was orthodox to read Greek but also that Greek sources often surpassed the Western tradition:

[C.] I want to know why Greek [sources] are preferable to the Latin, despite the fact that many Greeks were heretics and enemies of the Latins, and that they forged and changed many texts. A. Do you think one should reject all Greek texts? We shall not compare the sacred books with the Septuagint, therefore, nor with other old translations, or the New Testament; nor shall we read any of the Saintly Eastern Fathers. Then, Dionysius Areopagita, Athanasius, the three Gregories, Basil, John Chrysostom, and so many others wrote in vain. So many philosophers, physicians, and historians are for nothing, then, if everything seems suspicious to you. . . . One should have other Greek books, [which are] like sources from which streams and rivers flow. The Greek canons were mostly written in Greece, and you do not give me any reason why they are not more ancient and superior to the Latin ones. You see that the Latin translators are divergent and vague; who can better explain the meaning of a sentence than the one who wrote it? When you do business with Africans, Indians, or Persians, you use an interpreter. How much does he say imprecisely, or he adds on his own things not said by us or others, or he does not remember what has been said? C. The Greek texts are, therefore, preferable to Latin ones, as if the source of the Latin ones.Footnote 127

Agustín's explicit defense of Greek is noteworthy as a scholarly statement devoid of confessional inflection. Attachment to Greek remained orthodox in Tridentine Catholicism, even after the council declared the Latin Vulgate the official version of the Bible in 1546,Footnote 128 and Catholic scholars actively engaged in the recovery and editing of the Greek Church Fathers.Footnote 129 Agustín never exhibited much prowess in biblical scholarship himself, nor did he know Hebrew, but he was fully aware of the controversies regarding the study of the scriptural languages and the biblical translation. At times, he would distance himself from the Spanish intellectual world and purport to be an Italian scholar, but his formation began at Alcalá and Salamanca in the period shortly after the publication of the Complutensian Polyglot Bible (1520). In 1576, he wrote to Benito Arias Montano (1527–98), encouraging his friend to go ahead with a proposed treatise defending Hebrew—he noted, however, that Montano should still consult orthodox scholars beforehand.Footnote 130 He also appreciated the multilingual foundations of Christian traditions and referred in passing to the Arabic and Armenian texts of the councils in De Emendatione. But he believed them to be always less trustworthy than the Latin and Greek authors.Footnote 131 The emphasis on Greek as necessary for the emendation of canon law evidently originated in Agustín's study of the Roman civil code, where he similarly paid attention to the Greek components of the corpus, such as Justinian's Greek constitutions. His journey to the sources of civil and canon laws followed the same paths.

THE CONFESSIONAL EMENDATION

Philological emendation of scribal mishaps or the correction of proper names was the easy part of the work on the Decretum. There was no controversy about changing the name of Pope “Silverius” to the more correct “Silvester,”Footnote 132 or clarifying the identity of John Chrysostom, who was often mistaken in the Decretum either for Pope John VIII or Saint Chromatius.Footnote 133 Agustín pointed out smaller and bigger errors of this kind. Such changes were welcomed even by the Roman Inquisition when the censors scrutinized Baluze's reedition of De Emendatione in 1673.Footnote 134 Still, work on the Decretum also required dealing with heated and contentious topics. Gratian indiscriminately drew from a number of problematic collections of legal texts, which in the meantime had been demonstrated to be either entirely or partially forged. Agustín's unmatched erudition in manuscript material allowed him to repair many provenance chains, but he also knew that it was impossible to defend the integrity of the Decretum from a strictly humanistic perspective. How did Agustín, who earned respect and built his career on uncompromising devotion to scholarly precision, navigate the situation?

Among the most problematic fragments of early ecclesiastical traditions were the Donation of Constantine; the Apostolic Constitutions, especially the widely circulating section known as the Canons of the Apostles; and the papal letters preserved (actually composed) in the compilation of Pseudo-Isidore, which became notorious as the False Decretals. Texts recognized in the sixteenth century as doubtful had entered the Church's tradition at various points in history and circulated for centuries, justifying practices, customs, and claims. For Catholics, outright rejection of even the most obvious fabrications was problematic, since it could undermine the legal structure of the Church as well as larger claims about the continuity of ecclesiastical practices. Critical philology and history were the means mainly to reinforce the integrity of the institution, as canon law could not yet become an object of erudite interest in itself.

One way to work with the contentious material and steer clear of trouble was to avoid giving direct answers to the most delicate questions. Agustín never engaged in a forthright discussion on the Donation of Constantine. In De Emendatione, he followed Valla and exonerated Gratian by blaming Palea, the twelfth-century glossator, for adding the forgery to the collection—and never mentioned it in the treatise again.Footnote 135 Still, the context of this single remark is striking. It appears in chapter 6 of book 1, entitled “On Gratian's Major Errors,” which focuses on papal decretals and Pseudo-Isidore. Agustín mentions the Donation in the middle of a tricky discussion of early papal documents by Miltiades (r. 311–14), Eusebius (r. 309–11), and Damasus (r. 366–84). He first reveals how Gratian anachronically ascribed whole passages to Pope Miltiades, missing the fine stylistic points of the text and basic historical facts, and effectively made Constantine Christian before his baptism by Pope Silvester (r. 314–35): “Is it not apparent that it was far removed from that period, either because of the inelegance of the style, or those words which suggest that there were Christian rulers who held monarchical power [already then] and Constantine was the first among them. What? What is this talk about Constantine's baptism before the times of Silvester? And he also mentions the Council of Nicaea, which took place in the twentieth year of [Constantine's] rule [325] under Silvester.”Footnote 136 The critique revolving around anachronistic language and illogical event sequences is a spitting image of Valla's attack on the Donation. And so is the provocative rhetorical tone, uncharacteristic of Agustín's own style across the treatise. It must have been obvious to any educated contemporary reader that Agustín was not talking only about Miltiades's letter.

The remark on the Donation is flanked on the other side by a discussion of Saint Helena (ca. 250–ca. 330), Constantine's mother, and her pilgrimage to the Holy Land, its chronology, and the invention of the Holy Cross. Agustín again excused Gratian, who struggled to interpret the documents of the relevant popes, Eusebius and Damasus, correctly, but eventually admitted himself that it was sometimes impossible to reconcile conflicting pieces of tradition. Then he abruptly cut the discussion: “I see a problem [here]: these are indeed opposing and cannot be easily led to agreement. We either have to say that there is an error in that letter by Eusebius and Damasus's writings, or if we accept them, then we should reject everything else. But please put forward other errors of Gratian.”Footnote 137 That Agustín suspended further investigation of the contentious papal traditions is meaningful. Various sources of ecclesiastical legal traditions—papal decretals, the Donation, Canons of the Apostles, Pseudo-Dionysius, etc.—stood together. Rejecting one cast doubt on all others.

Agustín would also refer to the Donation in his Epitome of Old Papal Law but did not grant it a prominent place there. Writing to Pedro Chacón, he once offered a variant reading of a fragment of the Donation, which confirms an indirect but continuing interest in the text. However flawed, it became part of the Church's tradition.Footnote 138 Agustín clearly saw the advantages of keeping even problematic texts available, rather than refusing to investigate them entirely. This approach was as much dictated by the reluctance to question openly particular texts as it was consistent with Agustín's methodology across disciplines. In Diálogos de medallas, he recommended a similar approach to secular antiquities: “[A.] There are some fake [inscriptions] which can also be taken as good. . . . B. If they are fake, how can they also be good? A. I will provide a few examples to make myself better understood.”Footnote 139 Then follows a discussion about inscriptions created anachronistically but featuring authentic, original texts (e.g., taken from Pliny's prose).Footnote 140

Agustín doubted the Donation in private but even then, discreetly. When Francisco Torres (Turrianus, 1509–84)—his lifelong friend, a Spanish royal theologian at Trent, a member of the Correctors’ team, and a ferocious maker of Catholic propaganda—was preparing his defense of the early decretals and Apostolic Constitutions, Agustín expressly advised against writing anything that resembled Agostino Steuco's recent treatise attacking Valla's work on the Donation. Steuco (1496/97–1549) argued that Valla was ignorant of the Greek tradition of the Donation. While Agustín must have appreciated the book's philological ingenuity, he doubted the disproportionate effort put into defending uncertain causes, which in his view diluted the Church's position: “sometimes one gives up the authority of things that are certain to defend those that are not.”Footnote 141

Discussing the Canons of the Apostles, Agustín warned that rejecting the whole collection was dangerous: “If you reject all of these Canons, you are raising a major commotion.”Footnote 142 He recommended Torres's passionate apology of early papal documents but finished by saying: “It is good to adopt a via media between those who approve and those who disapprove [of the Canons].”Footnote 143 On the one hand, he followed the theological tradition that treated the Canons selectively (around fifty were accepted in the West as orthodox). On the other hand, he broke with the traditions of philological practice that either accepted or rejected texts in their entirety. Agustín demonstrated a similarly conservative attitude to Pseudo-Isidore. When he drafted a censure of the 1520 Paris edition of the collection, he explored the contents and structure of the compilation, looking for clues about its origins, rather than fulminating against it. He applauded Pseudo-Isidore, for his work made available many texts rejected by others as apocryphal.Footnote 144

In post-Reformation Catholicism, a scholar's attitude toward documents like the Donation, the Canons, and early decretals was a test of their loyalty to the papacy.Footnote 145 Deletion of the doubtful would create a philologically appealing situation. But Agustín would rather call for a compromise between philology and orthodoxy than deny the validity of contested documents entirely. He stopped at elegantly signaling the controversies, because he knew it was the wrong moment to offer radical solutions.

To defend the Catholic position in the sixteenth century often meant setting the pope and his prerogatives against the authority of the councils. John O'Malley has shown that the relationship between the pope and the bishops’ assemblies has always been troubled, despite endless attempts to define it.Footnote 146 Notwithstanding conflicting evidence, Catholic scholars exploring ecclesiastical history in the Tridentine period were expected to emphasize the pope's superiority over bishops. Such was the anxiety over the issue that in 1579 censors finally banned Nicholas of Cusa's De Concordia Catholica (The Catholic concordance) over its conciliarist views. The treatise was previously suspect for doubting the Donation and Pseudo-Isidorian decretals, but still tolerated. Agustín showed his obedience to Rome often. He structured his Epitome to underscore the authority of the Roman popes, and he may have planned a separate treatise on the papacy.Footnote 147 But he also used De Emendatione as an opportunity to subscribe to the required agenda. Discussing the sixth ecumenical council, he noted against all the evidence that he had gathered studying conciliar history: “It is the sole prerogative of the Roman Pontiff to convene, preside over, and confirm the acts of a universal council.”Footnote 148 A century later, Baluze contested this explicit statement in his notes to Agustín's treatise, which in turn earned him a Roman censor's fury.Footnote 149