Introduction

How did today's global international system evolve? Territorially-based sovereign states today encompass the entire world. Although scholars debate whether the state is weakening or transforming due to globalisation and the emergence of new actors, the discipline of International Relations (IR) largely agrees that the sovereign state is the central defining feature of the current international system. Indeed, the sovereign state and the international system organised around it are today so ubiquitous that we take them for granted and assume that the world was always thus and cannot be any different. But other forms of political organisation ‒ empires, city-states, and tributary systems ‒ have dominated for most of human history. The sovereign state and the international system organised around it are actually relatively recent inventions. How did the world transition from a system of empires to an international system of formally equal sovereign states?

This article explores the simultaneous expansion and homogenisation of the international systemFootnote 1 during the past two centuries. During this period the international system ‘expanded’ to incorporate a much larger number of entities as members, while simultaneously those members became more homogeneous as the international system converged around the political form of the sovereign state as the only legitimate actor in international relations.Footnote 2 The article argues that debates within and around intergovernmental organisations (IGOs) function as a mechanism by which the international system determines who its members are, and which rights and obligations those members are allotted. To be a member of an IGO is to have access to official international decision-making forums as well as unofficial networks, and such memberships convey practical benefits to states. IGOs are also sites of contestation over what the international system is and should become. IGO membership discussions both reflect and shape broader norms of the international system. That is, IGOs play a key role in the constitution of the international system.

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the effective criteria of IGO membership shifted dramatically. Nineteenth-century IGOs commonly included colonies and semi-sovereign states as full members. Membership discussions analysed in this article reveal the influence of three competing principles: great power privilege, the ‘standard of civilisation’, and universal sovereign equality. However, as the norms of sovereign equality, self-determination, and decolonisation emerged and took hold, the membership policies of IGOs also changed. At the urging of states in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, colonial possessions were purged from membership, to be permitted to rejoin only upon independence. I argue that this contestation over IGO membership played an important role in constituting the international system first as an arena for inter-imperial politics, and second as an arena for formally equal sovereign states exclusively. We can trace both the expansion of the system – the incorporation of a growing number of entities ‒ and its homogenisation ‒ convergence upon the sovereign state as the only legitimate form of political organisation ‒ through IGO membership debates.

Who were the drivers of the simultaneous processes of expansion and homogenisation of the international system? The traditional ‘expansion’ narrative argues that an essentially European international system gradually incorporated the rest of the world as other states were ‘admitted’ into the club.Footnote 3 In this narrative there is little room for non-Western agency. However, I argue that non-Western agency is crucial to understanding the transition of the international system from empires to sovereign states. While Western states advocated a continued flexible approach to IGO membership, and by extension participation in the international system, states in Africa, Asia, and Latin America led the push towards the adoption of a policy based on sovereign equality. In this, paradoxically, one of the core constitutional norms of the ‘European’ international system ‒ the principle of universal sovereign equality ‒ came to fruition at the hands of non-European actors. The article thus makes a contribution to the emerging field of Global IR.Footnote 4

Empirically this article examines debates within two prominent IGOs: the International Telegraph (Telecommunications) Union (ITU), established in 1865, and the Universal Postal Union (UPU), established in 1874. Today part of the United Nations (UN) system, their foundation predates the UN by more than seventy years. They are typical examples of the first IGOs established in the nineteenth century – the so-called international public unions that sought to coordinate the provision of new technologies to facilitate industrialisation and international trade.Footnote 5 These IGOs have never operated in isolation from broader international developments. The ITU and the UPU each focus on their own area of global governance – respectively telecommunications technologies and postal services – but debates within them also reflect broader norms of the international system, and in turn contribute to shaping those norms. I do not claim that these IGOs are the (only) site where new norms of membership originated, but they have been selected because their long histories and rich archival sources allow observation over the longest possible period.Footnote 6 Through a focus on the ITU and the UPU it is therefore possible to analyse changing debates about membership of the international system as it transitioned from a world of empires in the nineteenth century to a system of nominally equal sovereign states in the twentieth century.

The article makes novel empirical, theoretical, and methodological contributions to existing IR scholarship. Its empirical focus on membership policies and debates within and around the ITU and the UPU adds rich detail and nuanced understanding to the story of the transition of the international system. The focus on IGO membership debates is innovative for two reasons: first, it contributes to theory by exploring how these debates within and around IGOs serve as a mechanism for the constitution of the international system, and, second, by opening a new source of rich empirical material this is also a methodological innovation. Finally, the article's analysis of the transition from empires to sovereign states makes a further theoretical contribution to Global IR by confirming the importance of non-Western agency in the constitution of the international system.Footnote 7

The first section of the article reviews existing IR literature on the development of the international system and changes in its membership, and argues that discussions within and around IGOs offer a promising and underutilised source for observing the transition from empires to sovereign states. The second maps out changes in membership in the ITU and the UPU from the 1860s until the present day. The next three sections progress chronologically through three phases of debate within the two IGOs: their initial establishment and growth prior to the First World War, increasing conflicts over membership policies in the interwar period, and the end of colonial membership and victory of the sovereignty criterion after 1945.

Membership of the international system

Several different IR literatures engage, directly or indirectly, the question of how to define international system membership and how the system has changed over time. This section reviews existing literatures, and argues that debates within and around IGOs offer a promising and underutilised source for analysing the transition from empires to sovereign states. Discussions within IGOs reflect and shape broader international norms. These debates therefore permit analysis of the international system that is both comprehensive and historically sensitive.

Although this was not its primary purpose, the Correlates of War (COW) project has provided one of the most influential accounts of the international system's evolution because of IR's widespread adoption of its State System Membership List.Footnote 8 The dataset approach is ahistorical. It seeks to create a uniform definition of ‘state’, that is, system member, and identify which entities fulfil these criteria at which time. COW has been criticised both for its criteria and their application in individual cases.Footnote 9 The project's reliance on diplomatic relations with Britain and France, at the charge d'affaires rank or above, as a criteria for sovereignty prior to 1920 has led to a Eurocentric bias, so that countries in other parts of the world enter the dataset at seemingly random times, if they are included at all. Furthermore, the 500,000 population threshold prior to 1920, but no population threshold for League of Nations or UN members in the later time period, has led to size inconsistency in the dataset and an inflation of the number of states in the twentieth century compared to the nineteenth.Footnote 10 Its account of the evolution of the international system is therefore inaccurate.

Other scholars have sought to address these shortcomings by producing new system membership lists with uniform population criteria and more flexible understandings of sovereignty in the nineteenth century. Ryan D. Griffiths and Charles R. Butcher's 2013 International System(s) Dataset (ISD), for example, identified one hundred new states primarily in Africa and Asia. It showed that the number of states actually fell during the nineteenth century, before rising again after 1945.Footnote 11 The COW dataset, in contrast, portrays an expanding system membership since 1815. Although quantitative scholarship is crucial to discuss overall trends in the composition of the international system, it is of necessity an exercise in simplification. For a deeper understanding of the mechanisms behind these changes, we must turn to the more historically nuanced and richer descriptions found in qualitative work.

The English School's ‘expansion narrative’ is the most developed story of the international system's evolution.Footnote 12 The traditional narrative claims that the international system first emerged in Europe – often focused on the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 – before gradually incorporating the entire world. The ‘expansion narrative’ has been influential in IR, but has come under increasing criticism from historically and sociologically informed scholarship. Overall, the ‘expansion narrative’ offers a Eurocentric picture of a rational, ordered process emanating from Europe, with non-European states being ‘admitted’ into the essentially ‘European’ international system.Footnote 13 The narrative was supplemented by stories of how China, Japan, Turkey, and Latin American states adopted European standards and were gradually ‘socialised’ into the system.Footnote 14 Recent scholarship has instead highlighted interactions between events and processes in Europe and elsewhere,Footnote 15 and the important role played by non-European actors in adapting and changing ‘European’ norms to local circumstances or creating new global norms.Footnote 16

The concept of ‘expansion’ itself has been criticised because it reinforces Eurocentrism. To say that something ‘expands’ implies that it grows or spreads, but that its essential nature remains the same. Scholars have therefore argued for the adoption of alternative concepts such as ‘globalisation’, ‘stratification’, or ‘transformation’.Footnote 17 This article traces the transition of the international system, a process that included both ‘expansion’ (growing numbers), and ‘homogenisation’ (convergence around the sovereign state), but by this I do not mean to imply that the system was unchanging. On the contrary, the article highlights how contestation over meanings and boundaries was a crucial mechanism for the constitution of the system.Footnote 18 Over the past two centuries, the international system underwent massive changes as it transitioned from a world of empires to one organised around the sovereign state. Non-Western agency was a crucial factor during the transition process, particularly in the eventual adoption of IGO membership policies based on sovereign equality. In this, paradoxically, one of the key norms of the supposedly ‘European’ international system – universal sovereign equality – came to fruition at the hands of non-European actors.

A further influential strand of research on membership of and changes to the international system, focuses on questions of recognition, status, and sovereignty. These concepts are closely related: ‘status depends on recognition: it concerns identification processes in which an actor receives admission into a club once they are considered to follow the rules of membership’.Footnote 19 Admission into the ‘club’ of the present international system is said to hinge primarily on state sovereignty. Sovereignty is a core concept of IR, and it remains contested. At its heart, sovereignty refers to the idea that a state (government), if sovereign, accepts no internal equal and no external superior authority. But there is still debate over what this means in practice, what the criteria for sovereignty are, and how these vary historically and geographically.Footnote 20 Recognition, too, is contested, and both lawyers and IR scholars continue to debate what recognition means, how it affects statehood, and the role recognition plays in the constitution of the international system.Footnote 21

Contributing to the activities of IGOs can be a strategy for gaining status and recognition, as evidenced for example by Norway ‘punching above its weight’ in UN peacekeeping.Footnote 22 Indeed, seeking IGO membership can be a way to obtain recognition as a sovereign state, because sovereignty has become both cause and effect of IGO membership. In 2011 Palestine sought UN membership, and was successfully admitted to UNESCO, as part of its quest for recognition and support. Today, IGOs are defined by only having sovereign states as members, ergo; all members must be sovereign states. UN membership is therefore widely used as a proxy for sovereignty and membership of the international system.Footnote 23 This close connection between IGOs, state sovereignty, and membership of the international system, is another reason why a historical examination of changing membership debates within IGOs can help shed light on the transition of the international system over the past two centuries.

In a recent study of how Japan sought membership of the international system, Douglas Howland demonstrates both how non-Western states had agency, and the usefulness of an analytical focus on IGOs. Howland argues that Japan used UPU membership to gain advantage in negotiations with Britain.Footnote 24 Furthermore, IGOs such as the UPU and the ITU offered an ‘alternative mode of international order’Footnote 25 where entities could be admitted regardless of their sovereign status. Japanese officials discussed IGO memberships primarily in terms of how to enhance Japanese autonomy and rights. Ultimately, IGOs offered a space outside power politics where Japan could be treated as an equal with the European great powers.Footnote 26 Howland demonstrates how focusing on IGOs allows discussion of international system membership. Similarly, Daniel C. Thomas studied European Union membership norms to analyse how regions define their borders and decide who are eligible for membership.Footnote 27 This article takes such an approach one step further and uses the UPU and the ITU to analyse the overall transition of the international system from empires to sovereign states.

I contribute to IR scholarship in two main ways. First, I argue that debates within and around IGOs reflect and shape broader norms of the international system. These debates are not mere mirrors, but also function as a mechanism by which the international system decides questions of membership and attendant rights and obligations. It is therefore possible to examine these debates as a means of analysing changes in the norms of the overall international system. This is a theoretical contribution to constructivist and English School scholarship on the transition of the international system. It is also a methodological innovation that opens up a new source of rich empirical material in the archives of IGOs. Second, the article contributes to Global IR scholarship as it emphasises and confirms the importance of non-Western agency and contestation, and provides detailed discussion of how non-Western actors were crucial in the transition of the international system from empires to sovereign states.

Membership trends in the ITU and the UPU

IGOs were not epiphenomenal to the emergence of the international system; rather, through membership discussions, they were important in the social construction of that system. IGO membership played a constitutive role in framing legitimate forms of political organisation as the system transformed from one of empires to one centred on the sovereign state. When empires were in power, IGOs served as a site to perform the hierarchical character of the system. When smaller and non-European states began to contest this, IGOs became sites for determining the newly homogeneous system of formally equal sovereign states.

This section analyses changing trends in membership in the ITU and the UPU from the nineteenth century to the present day. These organisations are typical examples of the first IGOs created in the nineteenth century. Their long histories and rich archival sources allow us to observe changes in membership policies over the longest possible period, and they are therefore a good starting point for a discussion of the transition of the international system.

Established in 1865, the ITU was the first truly international IGO. Although the river commissions for the Rhine (1815) and the Danube (1856) were older, the ITU was the first IGO with an aim of universal membership.Footnote 28 The UPU, established in 1874, followed the ITU model. Both IGOs quickly grew to encompass a diverse and geographically widespread membership, and both saw intense debate over membership policies from the interwar period onwards. Unlike later twentieth-century IGOs, the ITU and the UPU allowed semi-sovereign states and colonies to be full members and to take part in decision-making processes alongside sovereign states. While the ITU today has abandoned the earlier flexible membership policy and presently consists of 193 sovereign states, the UPU still counts two ‘overseas territories’ ‒ British and Dutch ‒ among its 192 members.

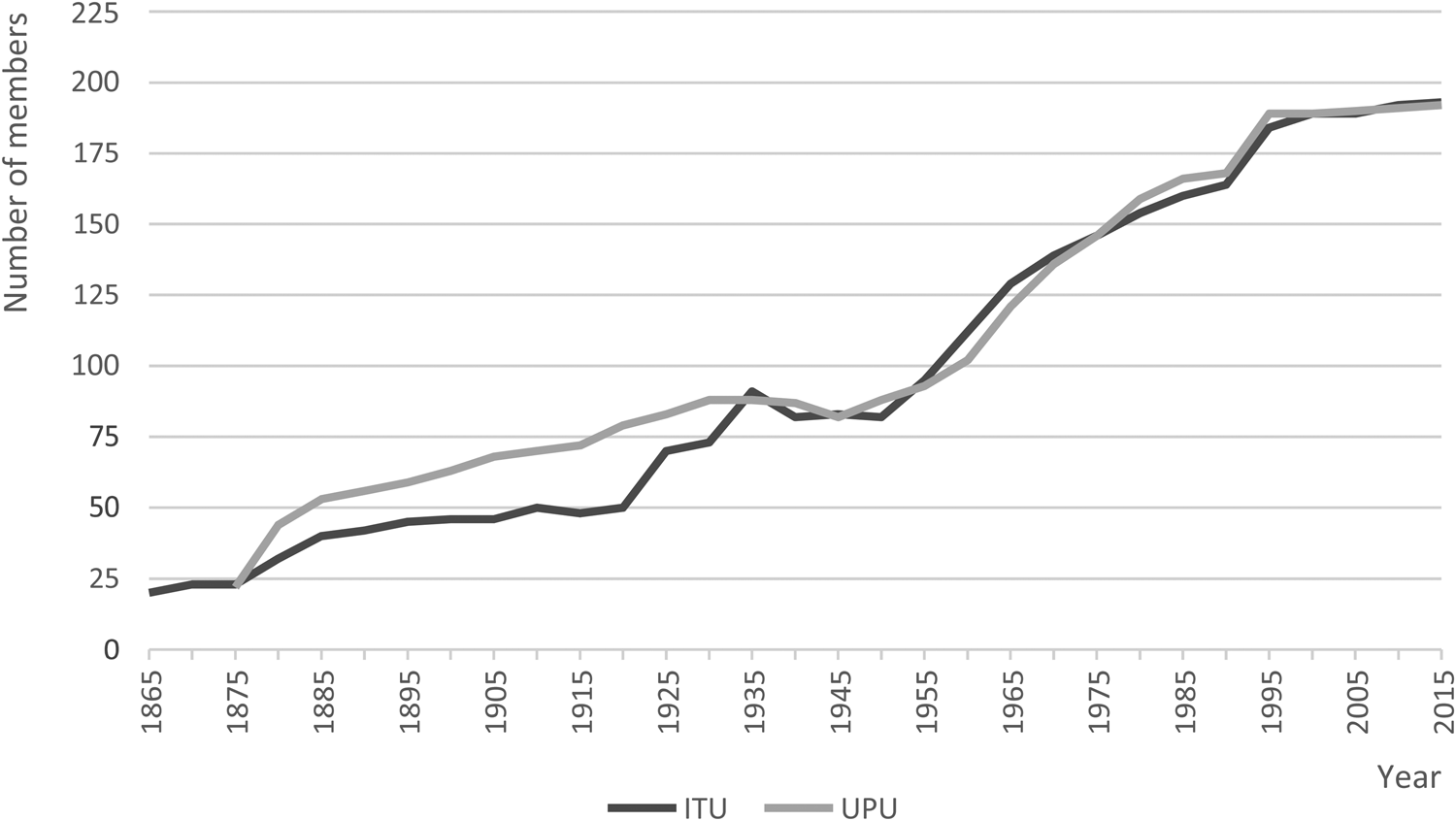

Figure 1 shows the growth of members in the ITU and the UPU. Both organisations allowed semi-sovereign entities and colonies to hold full membership. All these members, whether colonies, semi-sovereigns, or great powers, were treated as formally equal possessing identical rights and responsibilities (see later discussion). Figure 1 makes no distinction based on the legal status of members, but simply shows the total number as reported by the organisations themselves.Footnote 29 Both organisations had continually expanding membership, except during the Second World War. The UPU's membership grew more quickly than the ITU's in the nineteenth century, and it had a larger overall membership until the 1930s. Whereas the United States and most Latin American states joined the UPU from the start or by the early 1900s, the ITU remained a more European-centred organisation until its merger with the International Radiotelegraph Union in 1932. After the Second World War, both organisations continued to grow as newly independent states in Africa and Asia joined.

Figure 1. Membership of the ITU and UPU (1865–2015).

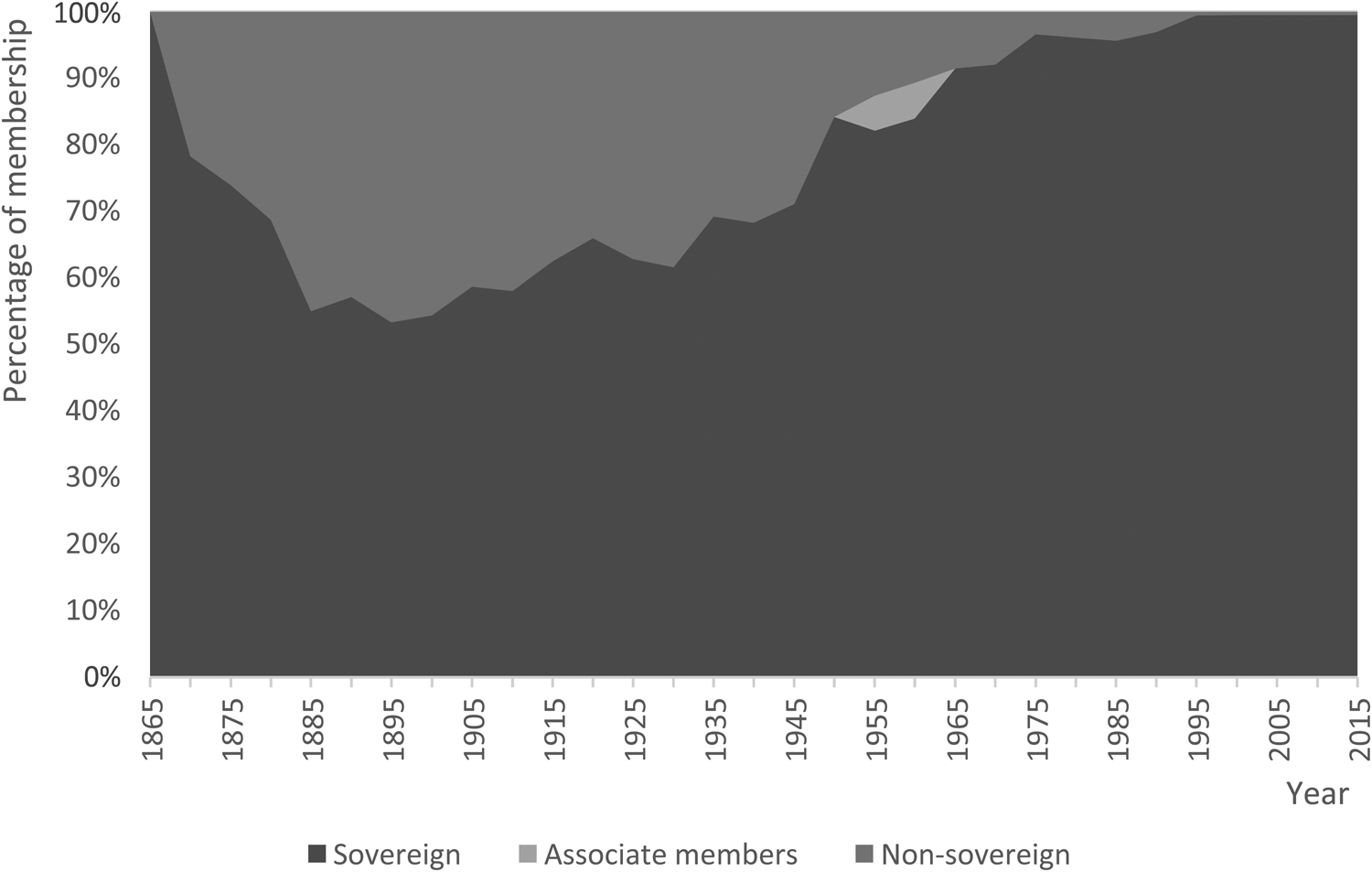

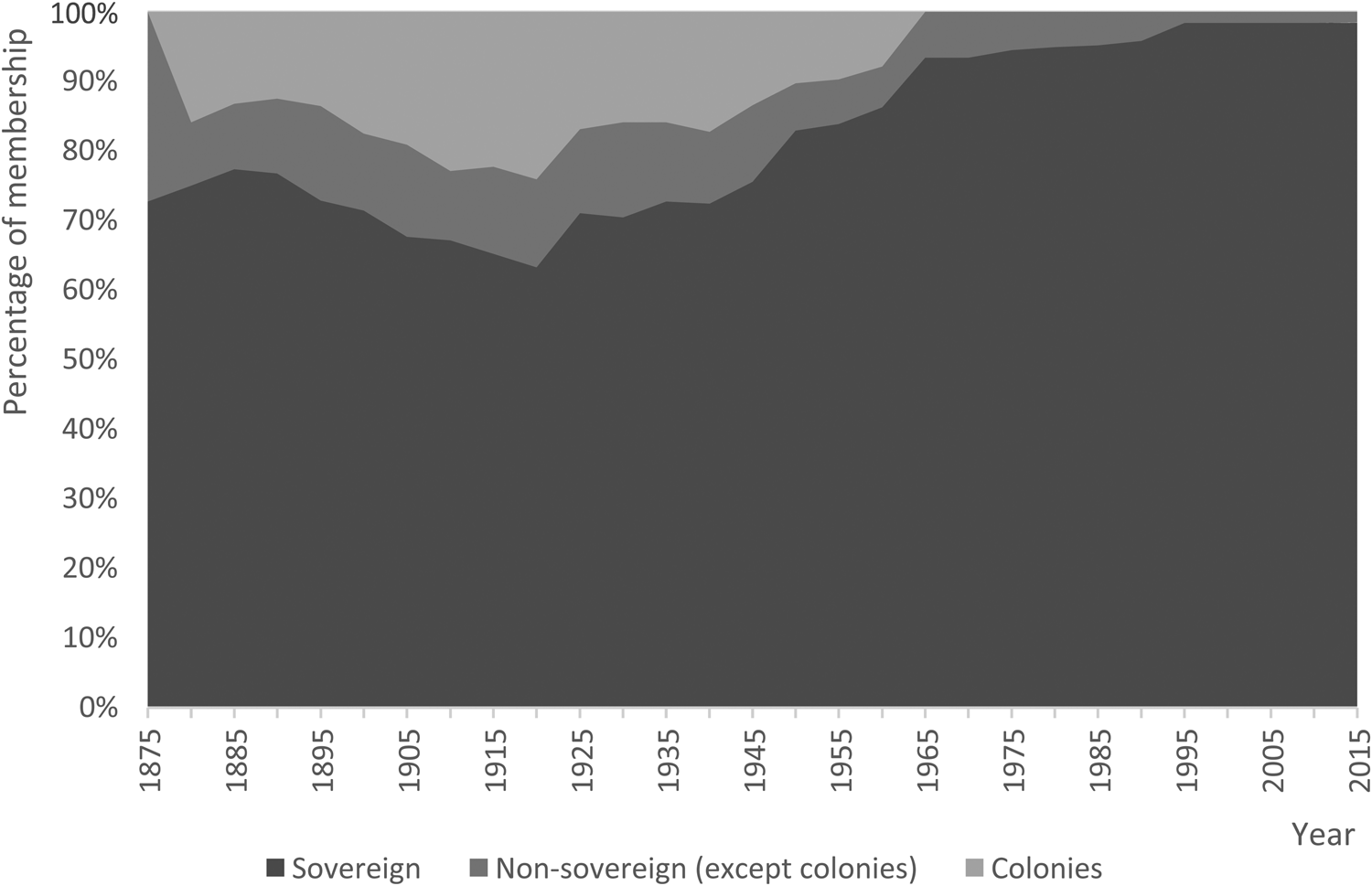

Figures 2 and 3 provide a visual representation of the significance of non-sovereign membership in the ITU and the UPU. To decide whether or not an entity should be considered a sovereign state at a given point in time, I have relied on information from the ISD.Footnote 30 This is the most recent, comprehensive dataset on the number and identity of sovereign states in the international system since 1816. I have used information from the ISD to classify ITU and UPU members as either ‘sovereign’ or ‘non-sovereign’.Footnote 31

Figure 2. Different categories of ITU members, as percentage of whole (1865–2014).

Figure 3. Different categories of UPU members, as percentage of whole (1875–2015).

Prior to the late twentieth century, the ITU included a significant proportion of non-sovereign entities among its membership. In 1895, 47 per cent of the ITU's members were non-sovereign. From then, the proportion decreased through the interwar and postwar periods, as larger numbers of sovereign states joined the organisation. The ITU made no distinction between these members based on their sovereign status. I have classified these members into ‘sovereign’ and ‘non-sovereign’ based on information from the ISD. All members of the ITU were subject to the same rights and obligations. In conventions and annual reports there is nothing to indicate that some of these members, such as Crete (member 1902–13), Egypt (member continuously since 1876), or French Indo-China (listed as separate member 1885‒1942), were anything other than normal members. The one exception to this rule was between 1947 and 1973 when the ITU allowed UN trust-territories and other non-sovereign entities to become associate members. Associate members did not possess the right to vote and could not be elected to the Administrative Council.Footnote 32 This category of membership was rarely used. In 1955 the organisation included five associate members, by 1960 this had increased to six, but by 1965 they had all left as their successor states gained independence and joined the ITU as full members.

The UPU displays a similar pattern of membership, as illustrated in Figure 3. Whereas the ITU made no formal distinction between members in its annual reports or conference documentation, the UPU convention included a ‘colonial article’ with a list of colonies that were treated as full members with all attendant rights and responsibilities. The UPU thus recognised that these entities were not sovereign states, but still awarded them full membership (as discussed later). Like the ITU, the UPU saw the largest proportion of non-sovereign members during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Counting colonies and other non-sovereign members together, the largest observation occurs in 1920, when 37 per cent of the UPU membership consisted of colonies or other non-sovereign entities. Throughout, the total proportion of non-sovereign members is somewhat smaller than in the ITU, probably because, as Figure 1 revealed, the UPU had a higher total membership prior to the 1930s. Apart from colonies admitted in a special process, other semi-sovereign states such as Bosnia-Herzegovina (1892‒1921), the Congo Free State (member since 1886, today DR Congo), and the Saar territory (1920‒35) were admitted and treated as normal members. Although contemporary and later scholars classify these as not fully sovereign, the UPU allowed them equal membership alongside sovereign states.

Although not every IGO in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries included colonies and semi-sovereign states as full members, the fact that many of them did was significant. A few IR scholars have noted that early IGOs included colonies and semi-sovereign states as full members, and usually attribute this to early IGOs’ greater emphasis on functional considerations instead of formal sovereignty.Footnote 33 This article's analysis confirms that functional arguments were important justifications for the decision to admit colonies and semi-sovereign states. But this was not the only consideration in these debates. Rather than looking solely to the question of why IGOs admitted colonies and semi-sovereigns, the article also considers what this practice signifies about broader norms of the international system. IGOs reflect the constitution of the international system, which, during the late nineteenth century, included both partially sovereign entities and imperial possessions. As a mechanism by which the international system determines questions of membership, these IGOs helped legitimate the system of empire and divided sovereignty. Once norms of sovereign equality, self-determination, and decolonisation started to take hold, these membership policies became the object of increasing contestation, which eventually led to policy changes. Over time, IGO membership reflected and impacted the wider system membership. As the international system underwent a dual process of expansion and homogenisation, so too did the membership of IGOs like the ITU and the UPU, and the discussion and conflict this entailed helped constitute the new international system based on the sovereign state. The contestation of and shifts in membership policies from the late nineteenth century to the post-1945 period is the focus of the remainder of the article.

Flexible membership in the late nineteenth century

Membership policies of IGOs both reflect and in turn shape broader norms of system membership. The following empirical analysis finds that three distinct principles can be observed in these debates during the late nineteenth century: the ‘standard of civilisation’, universal sovereign equality, and great power privilege. At the time, both the ‘standard of civilisation’ and great power privilege served to reinforce and legitimate the existing system of imperial hierarchies, while the principle of universal sovereign equality contained the seeds of the new international system of sovereign states. Through an examination of IGO membership debates, we can observe the conflicts between these different principles and how the international system settled on different compromises between them on the road to an eventual international system organised around the sovereign equality principle.

Reflecting their concern to attract as many members as possible to facilitate effective international telegraph and postal services in all parts of the world, both the ITU and the UPU chose very open membership policies. The 1865 ITU convention simply said that any état (state) not a party to the convention could adhere by giving notice, through diplomatic channels, to the host government of the previous conference. Any state adhering to the convention would automatically be subject to all obligations and benefits of membership.Footnote 34 The UPU likewise chose an inclusive route for membership, reflected in its decision to call its members pays (country) rather than état, and to change its name from the General Postal Union to the Universal Postal Union at the 1878 congress.Footnote 35 At the same conference, the UPU further adopted a nearly open door membership policy, identical to that of the ITU, allowing countries to become members simply by giving notice of their adherence to the Swiss government through diplomatic channels.Footnote 36 In this the membership policies of the ITU and the UPU were typical of the new nineteenth-century IGOs. Although some IGOs had more complicated application procedures or were limited geographically, the general principle was towards open membership. Paul S. Reinsch, a contemporary observer, noted:

The common law of international unions may therefore be stated to be that the unions are open to all nations who are ready to assume the burdens imposed, and that accession of all civilized countries will be encouraged. The purposes of these unions can of course be fulfilled best with a complete membership, including all the states of the world.Footnote 37

Although the IGOs themselves considered this an ‘open’ membership policy, in practice there were still some limitations on which entities could be admitted into the organisation. The requirement that new members give notice through diplomatic channels would have limited the pool of potential members to only those with access to such channels. Furthermore, Reinsch casually states that all ‘civilised countries’ would be encouraged to join, and that membership was open to ‘all nations ready to assume the burdens imposed’. This type of language is indicative of the ‘standard of civilisation’. The ‘standard of civilisation’ was a tool of nineteenth-century international law to distinguish between ‘civilised’ and ‘uncivilised’ states and peoples. The principle was used to ‘determine membership in the international society of states’.Footnote 38 At the time it was a ‘powerful mechanism for adjudicating the position of non-European societies in relation to European international society’.Footnote 39 By requiring all aspiring members to ‘act European’, it also drove the process towards homogenisation and the convergence around the sovereign state. Within the UPU and the ITU the standard for being ‘civilised enough’ for membership was the possession of a functioning postal or telegraph administration. This made the organisations more welcoming to non-European entities than some other parts of the international system.

The ‘standard of civilisation’ was not the only principle at play in IGO membership debates. A second principle of sovereign equality can be observed in voting policies and decision-making procedures. The voting policy in both the ITU and the UPU appeared to be very simple: ‘Each country has one vote.’Footnote 40 Conferences, additionally, tended towards taking decisions by unanimous consent. The unanimity principle at this time was a kind of customary law of nations. ‘No legal obligation could be imposed upon a sovereign state against its will; unanimity, in fact, was regarded both as a necessary consequence of sovereignty and as the best protection for it.’Footnote 41 The ITU and the UPU were somewhat unusual in relaxing the unanimity requirement. Although they preferred to take decisions unanimously, and meeting records are full of statements stressing conciliation and cooperation, when an issue came to the vote, a simple majority was sufficient.Footnote 42 Furthermore, ITU and UPU decisions, like those of other IGOs, were not binding on members. Members had to ratify conventions before they would enter into force, and they were also allowed to register reservations.Footnote 43 These policies are indicative of the importance of the principle of sovereign equality to the operations of IGOs, and how the activities of most nineteenth-century IGOs served to shield states from undue foreign interference and thus to preserve their sovereignty.Footnote 44

The importance of state sovereignty to the operation of these IGOs can further be observed in their decision to exclude private actors from full membership. ‘Open’ membership meant that any state-like entity with a government-run telegraph or postal administration could gain membership. The 1871‒2 ITU conference decided to allow private telegraph companies to participate in meetings, but to deny them the right to vote. The arguments used in favour of admitting private companies largely reflected the functional concerns of the organisation: these companies had their own interests and should therefore be heard in discussions, it was desirable to include them to benefit from their expertise, and it would be impossible to settle some questions unless the companies were on board.Footnote 45 Likewise, functional arguments were also used by those opposed to letting companies participate: the companies could be a disruptive element that would unnecessarily prolong debates and risk ‘drowning the discussion with multiple views’.Footnote 46 In addition to functional arguments, however, opponents also emphasised that companies should not be given an equal and independent status with states because ‘their natural representative is, in principle, the national representative’.Footnote 47 The compromise reached between the principle of state sovereignty and functional considerations was to allow the companies to participate in discussions but to reserve the right to vote for state (including colonial and semi-sovereign) delegations.

Finally, great power privilege was a third competing principle in the operation and membership policies of nineteenth-century IGOs. This is most clearly observed through the practice of admitting colonies to full membership. The question of colonial membership and voting rights first arose during the 1871‒2 ITU conference when Britain demanded a dual vote. Britain, at first, had not been an ITU member because its telegraph services were privately owned, but the telegraph administration in India was government-run, and therefore eligible for membership. On this basis Britain was invited to attend the 1868 conference, and there it signed the convention in the name of British India. By the next conference in 1871‒2, Britain had nationalised its domestic telegraph services, and therefore sent two delegations, demanding that each be given a separate vote.Footnote 48 Allowing Britain a second vote would break with the principle of sovereign equality of members and the voting rules based on it, but it would be a recognition of Britain's great power status.

Opponents of changing the system of one state, one vote, argued that there would be disadvantages to adopting a procedure that would allow each state to create additional votes for itself. If Britain were allowed a second vote, other states would soon claim the same privilege, and, argued the Belgian delegate, ‘there would be serious difficulties in setting the limits or stopping the further division of votes’ in the future.Footnote 49 But in the end the assembled delegates accepted Britain's demand for two votes because doing otherwise was outside their jurisdiction. They were there to discuss technical issues, and had no authority to challenge Britain on a political question of voting rights.Footnote 50

A few days later, the Netherlands was the next colonial power to claim additional votes, as it designated its delegate a representative both of the Netherlands and the Dutch Indies.Footnote 51 This elicited no further debate from the assembled delegates. One change was noticeable, however, in the addition of India and the Dutch Indies to the article detailing member states’ contribution to the International Bureau's budget. India was placed in the first class alongside the largest states contributing the biggest share of the budget. The Dutch Indies was allocated to the third class out of six.Footnote 52 From this point onwards, India and the Dutch Indies were treated as full members of the ITU, fulfilling all duties of membership and enjoying all benefits.

The laissez-faire attitude towards colonial memberships was confirmed at the next ITU conference in St Petersburg in 1875, which adopted a proposal to allow multiple votes for states that represented more than one telegraph administration, if the government notified its intentions through diplomatic channels before the start of the conference.Footnote 53 The proposal hardly elicited any discussion from the assembled delegates, indicating broad acceptance or toleration of the practice by this time.

The UPU also allowed colonial possessions membership, but it arrived at this position through a slightly different route, resulting in a more formalised approach to colonial memberships and voting rights than that found in the ITU. The original 1874 treaty contained a provision for admitting ‘countries beyond the sea’ on condition that they came to agreement with the existing membership on the cost of sea conveyance.Footnote 54 Following this procedure, Britain applied for membership for its Indian colony, and an 1876 conference decided to admit both British India and the French colonies.Footnote 55 The procedure of calling a special conference proved to be cumbersome, however, and the 1878 conference decided instead to insert a new article into the convention to list the colonies that would be considered full members of the Union, with all the rights and obligations this entailed. The list included British India, the Dominion of Canada, and the colonies of Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain.Footnote 56 From this time on, new colonial memberships could be added if the colonial power secured support to amend the article. By 1920, the list comprised 19 colonial territories.Footnote 57

Several reasons were provided as justification for admitting colonies, either individually or collectively, to full membership of the UPU. The basic criterion was whether they possessed independent postal administrations. Furthermore, UPU delegates felt that these colonies covered such large territories and populations, and therefore had their own attendant interests and problems, that it was desirable to allow them an independent vote in international postal matters.Footnote 58 Overall, the majority of discussion about colonial membership in the UPU concerned functional arguments. Like the brief nature of discussions at the ITU conferences of 1871‒2 and 1875, this indicated widespread acceptance or tolerance of this practice of great power privilege. When great power privilege came into conflict with the principle of sovereign equality, a compromise was found through inscribing these colonies as full members, and extracting from them the ordinary membership obligations in exchange for granting them membership privileges.

These discussions over colonial membership not only involved a conflict between the principles of sovereign equality and great power privilege. The ‘standard of civilisation’ also made an appearance through the silence on a related question: the situation of members like Norway. No one questioned why Sweden and Norway sent separate delegations, signed the convention separately, and paid separate budget contributions. As a junior partner in a union with Sweden, Norway was not a fully sovereign state by the standards of the time. Sweden conducted the union's foreign relations, and Norway should not have been able to adhere to the ITU as a state using diplomatic channels. The silent acceptance of Norway's separate vote, as opposed to the fierce debate over India's, was probably due to their different status. Whereas India was a colony where British nationals occupied senior posts in telegraph administration, Norway was a ‘civilised’ European ‘state’, and no one questioned the Norwegian telegraph administration's ability to conduct its own affairs. Norway's autonomy had a ‘taken for granted’ character that India's claim to representation lacked. Although it wasn't fully sovereign, Norway was a member of the ‘civilised’ club, and it therefore met no resistance when it joined IGOs as an individual member.Footnote 59

Norway's membership is an example of how the ITU and the UPU allowed semi-sovereign states to be members. As Figures 2 and 3 showed earlier, non-sovereign entities comprised a substantial proportion of the ITU's and UPU's membership in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Colonies formed part of this group, while the rest were made up of semi-sovereign states. The UPU had separate procedures for admitting colonies, but had no special requirements for semi-sovereign states. These members must have followed the standard admission process of notifying their adhesion through diplomatic channels. Notable examples, in addition to Norway, included the island of Crete, the Congo Free State, Egypt, Hungary, and Tunisia.

The presence of these semi-sovereign states in IGOs would seem like a contradiction of the principle of sovereign equality. The traditional ‘expansion’ narrative largely views the nineteenth century as an era of nation states, but recent scholarship has highlighted the importance of divided or shared sovereignty and the existence of semi-sovereign states.Footnote 60 Furthermore, the presence of semi-sovereign states was not merely a remnant of earlier times. During the nineteenth century the great powers actively created new semi-sovereign states in their efforts to engineer stability in the Balkans.Footnote 61 Semi-sovereign states were an inherent feature of the international system of empires that still dominated in the nineteenth century, and their inclusion as full members of the UPU and ITU further confirms that IGOs in this period served to legitimate and constitute the international system of empires.

Growing conflicts in the interwar period

The previous section explored how IGO membership policies in the late nineteenth century reflected three partially competing principles: the ‘standard of civilisation’, universal sovereign equality, and great power privilege. In recognition of great power privilege, IGOs allowed colonies full membership, while the presence of semi-sovereign states provided further evidence of how IGOs served to consolidate and legitimate the international system of empires. After the First World War, with growing numbers of formally independent sovereign states taking part in the activities of IGOs, and further diffusion of the principle of universal sovereign equality, earlier practices of flexible membership met increasing opposition from smaller states. Protests and conflicts followed, leading to a new compromise that shifted IGO membership policies one step further towards sovereign equality.

The ITU and the UPU did not operate in a vacuum, and in the interwar period the establishment of the League of Nations introduced a new element into the international system, which impacted membership debates in older IGOs. The League itself was open to ‘any fully self-governing State, Dominion or Colony … if its admission is agreed by two-thirds of the Assembly’ or if listed in the annex of original members.Footnote 62 The only colony ever admitted was India. Alongside the British Dominions of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa, India participated at the Versailles conference in recognition of its contribution during the First World War, and was an original member of the League of Nations. This recognition of the Dominions’ and India's international persona led to changes in their status within the UPU. Before the war they had been listed in the UPU's colonial article ‒ India and Canada from 1878, Australia from 1891, South Africa from 1897, and New Zealand from 1906 ‒ a position confirmed by the first postwar UPU convention of 1920.Footnote 63 However, at the 1924 conference the Dominions and India were upgraded to full membership status. Independent membership for the Dominions in the League, the UPU, and other IGOs, can perhaps be explained, like Norway's in the nineteenth century, by reference to the ‘standard of civilisation’, but despite their apparent ‘upgrade’, their position was no longer unquestioningly accepted by the broader membership.

In the 1920s the system of colonial memberships and voting rights had reached new heights. In the ITU by 1925, Britain, France, Italy, and Portugal each held six additional votes.Footnote 64 A growing number of small- and medium-sized states from Europe and Latin America worked to abolish or limit colonial membership. During the 1932 ITU conference the effort to limit colonial voting registered a partial success in a compromise, which reduced the number of colonial votes drastically. The debate concerned not only whether to preserve votes for colonies and Dominions, but also the established practice of giving additional votes to great powers without colonies to compensate for the colonial votes of others. The Greek delegate, for example, declared himself willing to accept some colonial votes – which had ‘a questionable, but moral, foundation and history’ – but protested vehemently against granting ‘compensation’ votes. This practice was ‘incomprehensible, novel, and dangerous. [It] led to controversies, and threatened to annihilate the voices of small states.’Footnote 65 After lengthy debate the conference agreed to grant one additional vote to the colonial powers Belgium, Britain, Italy, Japan, Portugal, Spain, and the United States, and two additional votes to France. It recognised the independent votes of India and the Dominions, and awarded one compensation vote each to Germany and the Soviet Union.Footnote 66 The deal was a renegotiated compromise between the principles of great power privilege and sovereign equality. Although great powers still wielded additional votes, this was a step towards recognising the principle of one vote per sovereign state, and it indicated the end of the complete free-for-all in claiming additional votes.

Inspired by the success in the ITU, opponents of colonial voting and great power privilege submitted several proposals for limiting the membership of the UPU before the 1934 congress. Switzerland proposed a limitation of colonial votes identical to the ITU compromise.Footnote 67 More radical proposals that would effectively abolish colonial voting came from two Latin American states. Argentina proposed that only sovereign states should be allowed to vote, ‘the criterion of sovereignty in cases of doubt being the maintenance of diplomatic representatives abroad’. Colombia suggested limiting voting rights to ‘Dominions or Colonies possessing an autonomous Parliament.’Footnote 68 The two proposals thus emphasised different aspects of sovereignty. The Argentinian proposal put a premium on the external dimension of sovereignty focused on diplomatic representation, while the Colombian proposal emphasised the domestic aspects in a state's autonomous government of its own territory signified by possessing a parliament. The Latin American states and their supporters sought to defend the principle of sovereign equality of all states ‒ as small states themselves this would give them more influence ‒ against the principle of great power privilege. In the end, the conference failed to reach agreement to either abolish or amend the system of colonial membership and voting, and the status quo continued until after the Second World War.

Internal British discussions from this period confirm the extent to which colonial votes were connected to great power privilege and inter-imperial competition. Britain, somewhat counterintuitively, decided to join the campaign against colonial votes in the UPU and the ITU. Although this might look like an altruistic act on the part of the greatest colonial empire of the time, it was motivated more by rivalry with France and other colonial powers, and an attempt to curry favour with the smaller states. It also displayed a certain arrogance and naiveté on the part of the British Foreign Office, and its ignorance of how others viewed the British Empire.

First, to British government officials, there was a clear difference between colonies and Dominions, which was less clear to other observers. Britain considered the Dominions, plus India, as truly separate administrations, which should be excluded from a comparison of ‘British’ and, say, ‘French’ votes. Whereas the French colonies were ‘mere pocket votes’ for Paris,Footnote 69 the Dominions were different, and ‘it [would] not [be] right to count them as they are completely independent’.Footnote 70 The Foreign Office failed to see that other states considered the Dominions to be ‘British’ votes. Indeed, the Latin American states sought to limit both colonial and Dominion votes.Footnote 71

Second, because of this peculiar British way of counting votes, when discounting the Dominions after 1924, Britain ‒ the largest colonial empire ‒ no longer had any colonial votes, whereas France had several, and even Belgium, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the US had colonial votes for colonies much less important than Britain's. This state of affairs was ‘absurd’, ‘obviously unfair’, and ‘ridiculous’, according to the Foreign Office, which advocated amending it in one of two ways: either to abolish colonial votes altogether, or claim additional votes for Britain.Footnote 72

Although colonies sometimes voted differently from metropolitan governments,Footnote 73 for Britain, other colonial empires, and states without colonial possessions, the question of colonial memberships had become mainly a question of great power politics. Given the opportunity, colonial empires would seek to secure as many votes as possible. Large states without colonial possessions, like Germany and Russia/the Soviet Union, saw the system as unfair, and claimed and received additional votes based merely on their size and importance. This practice of great power privilege went largely unchallenged before the First World War, but met increasing resistance during the interwar period when smaller states like Argentina and Colombia argued for the abolition of all colonial votes, in accordance with the principle of universal sovereign equality. They would ultimately succeed, once decolonisation brought new African and Asian members who joined their cause and gave them a numerical majority. The persistence of colonial and semi-sovereign memberships indicates that the interwar period was still one where the international system was dominated by imperial hierarchies, and this reality was reflected in IGO membership discussions. The increasing contestation of this reality and calls for reform along the lines of the principle of sovereign equality, reflected the broader trend of transition in the international system towards one where the sovereign state would become the only legitimate international actor.

Victory of the sovereign equality principle

In the decades after the Second World War the transition from an international system of imperial hierarchies to one organised around the sovereign state reached its (temporary) fulfilment. During this time IGOs stopped admitting colonies or semi-sovereign states, partly because the issue lost importance as former colonies gained independence, and partly because of policy changes. This section reveals that the ‘victory’ of the sovereign equality principle came largely at the hands of non-Western states. Non-Western states, once admitted to membership of IGOs, could use these forums to push through changes in the norms of the international system. Non-Western agency was crucial to the spread of the norm of sovereign equality in the twentieth century, and with it the simultaneous expansion and homogenisation of the international system. Thus, paradoxically, a core constitutional norm of the so-called ‘European’ international system was realised through the actions of non-European states.

Where the League of Nations influenced debates about membership in older IGOs during the interwar period, the UN assumed that role after 1945. The traditional narrative of the international system often dates the highpoint and final adoption of sovereign equality to 1945 and the UN Charter, Article 2 of which established that the organisation was ‘based on the principle of sovereign equality of all its Members’. In his study of postwar system-building, G. John Ikenberry called the 1945 settlement ‘history's most sweeping reorganization of international order’.Footnote 74 But although the UN Charter stated the importance of the sovereignty principle, certain anomalies continued in membership practices, indicating that the international system had not yet reached the highpoint of universal sovereign equality. The Soviet Socialist Republics of Belarus and Ukraine were founding members of the UN even though everyone acknowledged they were not sovereign states. The Soviet Union was afraid of being outnumbered and pushed for individual UN membership for its 16 constituent republics. A compromise deal with the Western great powers gave it three seats: Belarus, Ukraine, and the main Soviet Union seat.Footnote 75 The admission of Belarus and Ukraine continued the earlier practice of great power privilege, a principle that can also be observed in the Security Council, where China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States were given permanent seats and veto powers.Footnote 76 The UN thus reached its own compromise between the principles of sovereign equality and great power privilege.

When the ITU and UPU reconvened for their first postwar conferences in 1947, many interwar membership debates returned, now influenced by the establishment of the UN. Continued disagreements over membership criteria, rights, and categories left its mark on the 1947 ITU conference in Atlantic City. Latin American states, supported by the United States and the United Kingdom, argued for limiting membership to sovereign states, because this would bring the ITU ‘more nearly in conformity with the procedures and policies of the United Nations’.Footnote 77 They proposed a new category of associate membership to allow colonial territories with autonomous telecommunications administrations to participate in the work of the Union, but insisted such associate members should not enjoy the right to vote. Existing colonial members, supported by France and other colonial powers, argued against removing the full membership rights of colonies. The representative of the Dutch East Indies questioned the logic of promoting international cooperation ‘by excluding from full membership several totally independent telecommunication administrations, which cover vast areas of the world’. The delegation of the Belgian Congo reminded the conference that the ITU ‘constitute[s] a technical and administrative union’, and the Moroccan delegation likewise asked why ‘questions of sovereignty and political autonomy are suddenly linked to the question of the organization of the ITU’.Footnote 78 Such arguments were reminiscent of late nineteenth-century debates, when conference delegates also used functional arguments to defend granting colonies full membership.

In the end the conference reached a compromise to impose stricter admissions criteria for new members, while allowing all existing members to keep their full membership. From now on only sovereign states could become full ITU members, while UN trust territories and other non-sovereign entities could become associate members without the right to vote or eligibility for election to the Administrative Council or other ITU organs.Footnote 79 Existing members were listed in an annex to the convention, thus allowing colonies to keep their full memberships. In 1947 the list included the colonies of Belgian Congo, the Dutch East Indies, Burma, other British colonies, French colonies, Portuguese colonies, US territories, and the French protectorates of Morocco and Tunisia.Footnote 80 These colonies continued to participate at ITU conferences in the 1950s and 1960s.

The UPU went through a similar process at its 1947 conference in Paris. Although the conference discussed a proposal to remove colonial memberships, it decided to keep the status quo with regard to existing members. Potential new members, limited to ‘sovereign countries’, would have to be approved by at least two thirds of the existing membership, thus ending the earlier open door membership policy, but all existing members would keep their membership unaltered. A proposal for associate membership was debated and discarded, and the conference retained the convention article listing those colonies that were full members.Footnote 81 The UPU thus continued the earlier compromise between the principles of great power privilege and sovereign equality.

Colonial membership gradually lost importance as former colonies gained independence, joined the UN, and acceded to the ITU and the UPU. The category of associate member established by the ITU in 1947 was rarely used. Throughout the 1950s the UPU dropped names from the list of colonial members, although one exception was the agreement to add ‘the Territory of Somaliland Under Italian Administration’ in 1957.Footnote 82 A major revision of the UPU in 1964 removed the list of colonies from the new UPU constitution, but existing members were not expelled. Through a provision in the constitution stating that ‘Member Countries of the Union are: (a) Countries which have membership status at the date on which this Constitution comes into force’,Footnote 83 a few colonies and semi-sovereign states were grandfathered into the new UPU. To this day the UPU still counts two colonial (‘overseas’) territories ‒ British and Dutch ‒ among its 192 members.

The ITU saw a more dramatic end to the earlier flexible membership policies when the 1973 conference abolished all vestiges of colonial membership. The decision was intricately linked to the broader process of decolonisation and the changes taking place within the UN and other IGOs as a consequence of the new majority of non-Western states. Argentina, continuing its active stance from the interwar period, and Zaire, formerly the Belgian Congo, led the charge against colonialism and imperialism in the ITU. They received support from nearly all newly independent states, Latin America, and the Soviet bloc. France, the United Kingdom, and the United States were the most active on the opposing side. The majority of debate revolved around the use of the words ‘territories’ or ‘groups of territories’ in the convention. Newly independent states saw the presence of these ‘territories’ as equal members as an ‘insult’, and argued that since it was ‘synonomous [sic] with a colony or a military base [it] must be dropped so as to give moral support to peoples fighting for their independence’.Footnote 84

France, the United Kingdom, and the United States warned against deleting the terms ‘territories’ or ‘groups of territories’ because this would lead to the expulsion of five members, and argued against taking a hasty decision that would ‘deprive a Member of its rights’.Footnote 85 The UN observer warned against deleting articles dealing with UN trust territories, as any change to the trusteeship system required a change of the UN Charter.Footnote 86 Even countries like Jamaica and Venezuela warned against expelling all ‘territories’ outright because this would exclude a number of small island states that were unable to bear the full costs of independence, and Malawi urged the conference to ‘take care not to overlook valid reasons for retaining the reference to territories by being over-zealous in its opposition to colonialism’.Footnote 87 But the coalition of states against colonialism and imperialism were not swayed by such arguments. The conference decided to delete all references to the term ‘territories’ in the convention; to remove the British, French, Portuguese, Spanish, and US territories, as well as Rhodesia, from the list of members; and to abolish the category of ‘associate member’.Footnote 88 With this all vestiges of colonial membership were removed from the ITU convention.

Timing was an important factor, which might explain the more confrontational process at the ITU compared to the UPU. Where relations between developing and developed states were characterised by optimism in the 1960s, by the 1970s this had given way to conflicts and pessimism.Footnote 89 In the 1970s the Third World grew tired of waiting for change to happen through joining the existing organisations, and instead sought to alter the international system through initiatives such as the New International Economic Order (NIEO).Footnote 90 The more confrontational end to colonial membership in the ITU might therefore be the result of more hostile relations between the developed and developing world in the 1970s.

The expulsion of Rhodesia from ITU membership in 1973, and the related suspension of South Africa's membership from the UPU (in 1964), the ITU (1965), and the UN (1974), indicate that the version of ‘standard of civilisation’ that had influenced IGO membership policies in the nineteenth century was no longer a legitimate norm in the international system. Where earlier this principle had served to include semi-sovereign European – ‘white’ – states while excluding non-European ‘savages’ and ‘barbarians’, post-1945 such overt racist discrimination was unacceptable. Settler colonialism and white minority rule had lost legitimacy in a world where all peoples had gained the right of self-determination.Footnote 91

Newly independent states of Africa and Asia, alongside the states of Latin America, led the campaign for new membership policies based on the sovereign equality principle. Defending universal sovereign equality, they sought to expel anyone not sovereign. Sovereign equality was their main claim to actorhood on the international stage and membership of the international system.Footnote 92 Defending the principle of sovereignty, these states were protecting not only their right to be included in the organisation, but the very basis of their survival. The victory of the sovereignty principle, for the time being at least, thus came at the hands of the former outsiders, while the older core members of the system argued for a more flexible and pragmatic approach to membership. In this, paradoxically, one of the core constitutional norms of the supposedly ‘European’ international system ‒ the principle of universal sovereign equality ‒ was realised at the hands of the non-European states. This highlights the importance of non-Western agency in shaping the global international system, and in driving the dual process of expansion and homogenisation of that system. It also illustrates how debates within IGOs served as a mechanism for changing the norms of the international system, as non-Western actors were able to use the platform offered by IGOs to further their cause.

Conclusion

IGOs are sites of contestation over what the international system is and should become. IGO membership debates both reflect and shape broader norms of participation and legitimate forms of political organisation. Over the past two centuries, the international system has not only grown to encompass the entire world, but has also transformed from a system of empires to one organised around the sovereign state. This dual process of expansion and homogenisation can be traced through changes in membership in IGOs. Contestation over IGO membership was one mechanism whereby the international system converged on its present global form and composition.

The first nineteenth-century IGOs included colonies and semi-sovereigns as full members alongside sovereign states. Membership policies reflected a compromise between the principles of great power privilege, the ‘standard of civilisation’, and universal sovereign equality, and contributed to legitimise the existing international system of imperial hierarchies. However, once the norms of sovereign equality, self-determination, and decolonisation took hold in the twentieth century, those flexible membership policies became untenable. Contributing to Global IR scholarship and confirming the importance of non-Western agency, this article shows how, in a process driven largely by non-Western states, colonial possessions were purged from IGO membership rosters, to be permitted to rejoin only as formally sovereign states. In the post-1945 period, non-Western states drove the realisation of IGO membership policies, and an international system, based on the principle of universal sovereign equality. In this, paradoxically, a core norm of the supposedly ‘European’ international system was realised at the hands of non-European actors. IGOs such as the UN, the ITU, and the UPU provided a forum where non-Western actors and their allies could push for change. Debates within IGOs are thus a mechanism for change and contribute to the constitution of the international system.

Debates over membership of IGOs and the international system continue today. In the early twenty-first century, democracy has emerged as a fourth principle, which today influences discussions over participation in the international system. Arguments about democracy, transparency, and representation can be observed in calls for inclusion of NGOs in the decision-making process of IGOs, in demands for greater representation for women, or in debates about ‘local ownership’.Footnote 93 More influential private actors are another factor that is changing contemporary global governance.Footnote 94 In this regard we may note that the ITU allowed private companies a voice (but not a vote) in discussions from the start, and has continued to include more private actors than many other IGOs throughout its history. The present call for inclusion of private actors and representation for a broader array of interests is therefore not entirely novel, but rather signals a return to earlier forms of more flexible criteria for inclusion and membership such as those of the first IGOs from the nineteenth century.

Acknowledgements

From the initial idea, through its numerous drafts, and to the final published version, this article benefited greatly from discussions at the International Studies Association and European International Studies Association conferences, and the helpful comments and suggestions of colleagues in the STANCE research project at Lund University, and the Department of International Relations at the Australian National University. Special thanks to Jens Bartelson, Mathew Davies, Luke Glanville, Agustín Goenaga, Mary-Louise Hickey, Cecilia Jacob, Joseph MacKay, Jan Teorell, Alexander Von Hagen-Jamar, and Jeremy Youde. Thanks also to the three anonymous reviewers and the editors of RIS. Research for this article was supported by a grant from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (programme grant M14-0087:1).