Introduction

Ritual activities occur every day in both domestic and international politics. EU summits of heads of States, UN General Assemblies, COP conferences, Nobel Peace Prize ceremonies, and other similar interactions contain a ritualistic character that has recently come to scholars’ attention. For example, Shirin Rai highlighted the ritualistic dimension of parliaments, Eszter Salgo described the EU's efforts to ritualise its summits and other events, and Dario Paez, Zohar Kampf and Nava Löwenheim, and Danielle Celermajer analysed official apologies as a prominent international political ritual.Footnote 1 In many ways, these recent interventions build on David Kertzer's seminal study of political rituals, which brought attention to a broad range of non-religious political rituals, bringing back and adapting classic theories from Anthropology. ‘Ritual’, he claimed, ‘is an integral part of politics in modern industrial societies; it is hard to imagine how any political system could do without it.’Footnote 2 Jeffrey C. Alexander agrees: ‘symbolic ritual-like activities’ do not solely pertain to religion or ‘primitive’ societies, but still abound in contemporary societies.Footnote 3 While these contributions together already offer excellent insights into the complex dynamics at play in contemporary political rituals, much analytical work remains to be done. In particular, we observe that although the multiplication of studies in recent years has considerably enriched the analysis, it has also dispersed the theoretical landscape towards conceptual directions as diverse as emotions, securitisation theory, practices, performance, or visuality. In this context, the present contribution seeks to pull these threads together into a coherent framework that sheds light on the many dimensions and processes involved in rituals.

Specifically, we articulate this framework from the perspective of political rituals’ paradoxical nature: we highlight the multiple dynamics involved in rituals as they simultaneously unite and divide people and communities. For a long time, scholars working within the Durkheimian tradition have emphasised the integrative function of rituals, which are presented as moments where the unity of the group is asserted and performed. Yet the more recent literature has complemented that classic stance by highlighting the fact that rituals are often vectors of social fragmentation and intergroup tension; they can divide societies, sharpen oppositions between communities, or shape polarising self- and other- perceptions. The stability and unity they create has often violent and disordering effects.Footnote 4 While still ‘understudied and poorly understood’,Footnote 5 this sometimes divisive or fragmenting impact of rituals (probably first highlighted by Steven Lukes),Footnote 6 has been documented by researchers like RaiFootnote 7 or Kampf and Löwenheim who stress that ‘alongside the integrating power of ritual is its potential to magnify divisions between communities’.Footnote 8 The most notable recent intervention on the topic – a forum exploring a range of recent cases – even titled on rituals as ‘practices disordering things’.Footnote 9 What is now needed, we argue, is a coherent and systematic analytical framework that explains this duality by clarifying the conditions under which rituals both at once foster peace and fuel conflict. We spell out the dynamics that are involved in producing, for every political ritual, a specific configurations in terms of (dis)integrative effects. We develop such a framework by systematically situating rituals within their broader social environment, taking into account both how multiple groups may relate in different ways to a ritual (especially in today's globalised world), and how different dynamics and levels of ritualisation trigger different social outcomes in terms of cohesion and fragmentation. In other words, we aim to clarify the parameters shaping political rituals’ ever-specific configurations of integration/division.

To do so, we zoom out the theoretical lens by situating rituals within social ‘occasions’. Erving Goffman defined occasions as a ‘wider social affair, undertaking, or event, bounded in regard to place and time and typically facilitated by fixed equipment; [… which] provides the structuring social context in which many situations and their gathering are likely to form, dissolve, and re-form, while a pattern of conduct tends to be recognised as the appropriate and (often) official or intended one.’Footnote 10 Goffman's approach to occasions was an attempt to map and organise different levels of ‘interaction order’, which comprise the following nested strata: ambulatory units, contacts, conversational encounters, formal meetings, platform performances, and celebratory social occasions.Footnote 11 An occasion-model of interaction order was outlined in Goffman's 1982 American Association of Sociology presidential address delivered in absentia due to a crippling illness. A focus on occasion lets us explore each component of the nested strata while we look at the dynamic between them. However, an occasion does not necessarily feature all of the levels; instead, occasions embed other strata in degrees and it is not the case that occasions must include the complete set of strata constitutive of interaction order. Put another way, levels are both relatives and separates, which creates ambiguities. We follow Adam B. Seligman's and Robert P. Weller's lead in explaining ritual's ability to enable individuals to live with ambiguity.Footnote 12 We argue, however, that when rituals are nested in performances, the capacity of their subjunctive world enacted by rituals collapses and the ability to countenance ambiguity is stretched.Footnote 13 Performances, that is, replace ritual's requirements of getting it – conventionally – right with the demand for authenticity in one's actions and beliefs.Footnote 14 Including ritual and performance within itself an occasion-oriented model of interaction order casts light on how both the functions and outcomes of ritual – integrative or fragmenting – change with the patterns, resources, and properties that constitute occasions’ ‘structuring social context’.Footnote 15 The article indeed shows that the crucial mechanism in this dynamic approach to rituals takes a dual orientation, namely, the ritualisation of performance and the performance of rituals. In the former, ritual conventions are tasked with driving performances. In the latter, by contrast, performance's features are brought to bear upon ritual enactment. Thus, ambiguities about the functions and effects of rituals are closely entwined with the swinging boundaries between ritual and performance.Footnote 16

The article proceeds in three steps. We found it useful to open with the first section reviewing the classic, dominant, chiefly functionalist approach to political rituals, which emphasises their effects in terms of social cohesion. Consolidating this approach with recent research in psychology, we highlight the key social and emotional dynamics at play in what we call rituals’ logic of integration, which remains the analytical baseline from which any further conceptualisation of rituals’ impact ought to be built.Footnote 17 The second section situates rituals within broader social occasions that present more or less high degrees of ritualisation. This theoretical move allows us to move beyond the classic approach to tease out the circumstances under which rituals’ logic of integration might be complemented by one of fragmentation. Section 3 demonstrates the empirical usefulness of this new framework for the study of political rituals in an age of transnational audiences and communities, with a comparative case-study of two ‘most similar’ casesFootnote 18 of large and ritualised crowd gatherings that followed terrorist attacks. The ‘flower march’ organised in Oslo in July 2011 and the ‘Republican marches’ that followed the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris in January 2015 are discussed using our theoretical framework to understand why the latter produced comparably more division than the former. This study shows that when leaders deploy, in situations of national stress (for example, national mourning, war, terrorist attacks), ritualised occasions in order to reactivate national bonds, alleviate fear, or improve resilience, they might also trigger tensions and discontent. This is because such circumstances increasingly involve a variety of participants – internal and external – thanks in part to new mass media technologies, which change the dynamics of sensibilities on which rituals rest. In other words, although rituals can mediate collective grief and disguise conflicts, it can also disclose conflicting emotions and deepen disagreements over the object of national mourning.Footnote 19

The aim of this article is thus to consolidate the now thriving yet dispersed discussion on ritual in Political Science and IR in two main ways: one theoretical, the other empirical. First, theoretically, we offer a coherent framework that strengthens the conceptualisation of political rituals in contemporary societies, highlighting their global dimension and spelling out their multiple components to explain variation in their dual, integrative/fragmenting character. We bring together a range of different conceptions of rituals in order to integrate both the functionalist approach usually associated with the Durkheimian tradition and the approach of conceptualising rituals as performances. This framework connects with a range of core concerns of contemporary IR theory, such as how international practices constitute order or drive change, how salient group identities are constructed through non-linguistic processes, how emotions constitute political orders, or how domestic and transnational social movements get constituted and are perceived from non-participants in ways that often feeds polarisation. Second, empirically, we use this framework to emphasise the ritualistic nature of societal responses to extreme political shocks such as terrorist attacks. Attuning to the many functions, dynamics, and dimensions of ‘terror rituals’ not only helps to make sense of societies’ reactions to such events, but also paves the way for a richer understanding of some of the most fundamental mechanisms of social stability, fragmentation, change, and conflict. This second contribution expands and sharpens the investigation of ‘disaster rituals’ opened by Post and colleagues, and mirrors the growing literature on the ritual activities that accompany terror operations themselves.Footnote 20

Rituals’ logic of integration

The Durkheimian heritage

The study of rituals is, at its onset, closely associated with Anthropology, with major figures such as James Frazer, Bronislaw Malinowski, or Clifford Geertz having published work on rites and ceremonies in non-Western societies.Footnote 21 However, Emile Durkheim not only kick-started this interest but also, as we recall below, set the basic tenets of the theoretical prism through which rituals would later be seen.Footnote 22 These key figures tended to associate ritual with religion (and more particularly to religious practices in societies seen as more ‘primitive’ than the West); anthropologist Gordon George, for example, defined it as ‘a pattern of defined behaviors, externalizing in a sensible form some religious emotion or idea’.Footnote 23

More recent scholarship has expanded the scope of the concept of ritual, acknowledging the resemblance between religious practices understood as rituals and formally similar non-religious ones. Kertzer's book Ritual, Politics and Power, offered a minimalist – and therefore broad – definition of rituals as a ‘symbolic behavior that is socially standardized and repetitive’.Footnote 24 Rather than focusing on the domain within which rituals take place (that is, religion), he only set formal criteria, chiefly the ‘highly structured, standardized sequences’ that structure rituals and the ‘certain places and times that are themselves endowed with special symbolic meaning’ within which rituals take place.Footnote 25 Similarly for Post and colleagues, a ‘ritual is a symbolic action, whether religious in nature or not, with a more or less fixed, recognisable and repeatable pattern or course … involving stylized, formalized acts that moreover take place according to a fixed and repeatable pattern’.Footnote 26 This definitional broadening and its focus on formal patterns is now reflected in most dictionaries. For instance, the two definitions offered by the Oxford Dictionary of English assume that there is no necessary link between ritual and religiosity. Instead, they insist on the formal criteria of standardised sequencing of actions.Footnote 27

Most scholars have used these or similar definitions to emphasise the integrative function of rituals, which are understood to strengthen the bonds between the members of a society. In this context, Durkheim's The Elementary Forms of Religious Life has considerably shaped our understanding of rituals for decades. His approach is dubbed ‘functionalist’ to indicate that it centres on what ritual allows or makes possible, rather than, for example, on its composition. For Durkheim, indeed, ‘political rituals provide the integrative glue for societies’, whereby ‘worship of a god is the symbolic means by which people worship their own society, their own mutual dependency’.Footnote 28 In addition to demarcating the sacred and the profane, rituals serve to ‘revivify the most essential elements of the collective consciousness’.Footnote 29 Thus, the sacred ultimately refers not to a supernatural entity, but rather to people's emotionally charged interdependence, their societal arrangements. What is important about rituals, then, is not that they deal with supernatural beings, but rather that they provide a powerful way in which people's social dependence can be expressed’.Footnote 30 Rituals, in this sense, follow a logic of social integration, fulfilling an overarching social function through which they give a group individuality and identity.

This Durkheimian orientation still permeates contemporary scholarship. In his essay The Ritual Process, Victor Turner for instance famously argued that rituals are societies’ most privileged moments to integrate into a ‘communitas’.Footnote 31 As such, rituals are always political, in the sense of group creating, especially in moments when group cohesion is under threat or has been destabilised. In IR, Kampf and Löwenheim pushed that argument forward, holding that ‘rituals are widely found in politics because they have the power to integrate and reconstruct a national community around extraordinary events’.Footnote 32 As this quote illustrates, rituals are all the more important in times of crisis or shock, because they hold the potential to reinstate a possibly fragmented society. This integrative function is mainly achieved through the embeddedness of symbolic elements into the standardised ritual process. In a catholic mass, for example, the priest has particular clothes, uses a specific glass for the wine, stands next to the altar and candles, and the church is decorated with numerous crosses and other symbols. A US presidential State of the Union is no less filled with symbols: among others, the president is always introduced by the two Sergeants at Arms (from the House and the Senate), always proceeds to stand at the same spot, in front of the vice-president and the Speaker of the House, each of whom is given a folder containing the speech, and both of whom sit in front of a big American flag.Footnote 33 In the same vein, Salgo shows how EU officials have been working towards the codification of special events in EU politics and embed into this codification a range of ‘sacred symbols of European federalism’,Footnote 34 in order to reinforce a sense of European belonging. These symbols represent the perennial existence of the group, and through the meaning they condense, they project its identity and main values.Footnote 35 Their integration in a ritual process therefore reasserts the existence of the group and its idealised identity. The Nobel Prize ceremony follows a comparable enmeshment of symbolic elements into the scripted unfolding of actions (for example, the big golden reproduction of the Nobel medal on the rostrum from which announcements are made, the large ‘N’ on the blue carpet designating the spot where the prize is delivered). For Josepha Laroche, for example, the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony is a repeated, highly codified practice whose displayed symbols establish an international community of organisations and individuals sharing a common set of non-violent, anti-state moral values.Footnote 36 Further, some rituals involve the representation or glorification of ‘heroes’ who similarly condense the identity of the group. Hence, rituals do not simply serve a social, bonding function, but also have an ‘ethical’ function through which the preferred norms and values of the group are crystallised and reasserted.Footnote 37 Despite their differences, Bronislaw Malinowski and Alfred Radcliffe-Brown both put forward this idea that rituals operate the ‘reintegration of the group's shaken morality and the re-establishment of morale’.Footnote 38 Coming from a different theoretical perspective, Goffman's definition of ritual as a ‘conventionalized act through which an individual portrays his respect and regard for some object of ultimate value’ also reflects this view according to which the repetition of stylised and symbol-laden actions connotes obedience to a particular normative order.Footnote 39 As Ida Marie Høeg explains, ‘attendees [to a ritual] mutually show one another that they share in the moral community and become aware of the moral relationship which unites them’.Footnote 40

Portrayed in this way, rituals’ power of (re)integration plays a key role in power relations. The reader must pause here. Certainly, a key Durkheimian insight is that ritual empowers participants to do certain things together. The argument is stronger than it may seem, however. It involves the capacity to cause certain outcomes (for example, collective effervescence, emotional contagion, etc.). Ritual, so to speak, induces behaviours that only take form when participants are assembled; it is the situation that empowers participants.Footnote 41 Relatedly, rituals are assumed to effect the constitution of a group separate from others. Besides, a less discussed association between ritual and power concerns the distribution of power between participants. Indeed, some participants, by their office, may enjoy more power than others, including the choice of symbols and the selection of participants. Be that as it may, the integrative power of ritual can elicit different reactions from those excluded – resisting, being indifferent, crafting a counter-ritual by, for instance, and cultivating alternative symbols.Footnote 42 Conflictual impulses of rituals arise therefore when they pit ritually included members against ritually excluded.Footnote 43 In this perspective, ritual is both an engagement with and a performance against. We fully unpack this duality in our second section below.

Rituals’ reinforcement of a sense of common belonging to a community supposedly united by specific moral values, indeed contributes to legitimise society as it stands, with its inherent hierarchical system. For Kertzer, rituals are ‘employed to create political legitimacy’.Footnote 44 Salgo's abovementioned analysis of the European ‘civil liturgy’ stresses that its ultimate goal is to ‘legitimise itself’.Footnote 45 This dimension has been denounced several times, not least by Pierre Bourdieu, whose focus on the legitimising role of rituals in socially stratified contemporary societies led him to assert that ‘all and any rite serves to legitimate’.Footnote 46 Because they are, by definition, unreflective, almost automated standardised actions, rituals indeed ‘discourage any critical re-examination or debate’.Footnote 47 The various roles of ritual's participants are codified and correspond to a strict distribution of privileges, ritual possess the function of ‘inculcating and validating roles in society at large’.Footnote 48

In sum, the study of rituals in the social sciences has been heavily influenced by the Durkheimian intuition that rituals work at the societal level, implementing a logic of integration whose implications in terms of power and exclusion have not totally escaped scrutiny. They exhibit ‘a robustly collective dimension; the acts are performed by a group, a community, and that community is in turn bound together by the ritual act’.Footnote 49

The psychological addition

This line of research has never been able to provide a precise understanding of the mechanisms through which cohesion is actually achieved; this explanation has been given by social psychological research on collective emotions, which has recently trickled down into IR. In this literature, rituals have been said to trigger emotional dynamics that reinforce social bonds. Participation in ritual indeed always ‘involves physiological stimuli, the arousal of emotions’.Footnote 50 This emotional reaction is perhaps the main driver of the logic of integration: the cohesion of the group is primarily effectuated when the individuals who take part express identical emotions, hence creating a sense of common belonging. Ritual amplifies shared experience through the development of a communion among participants and the creation of emotional bonds. Reading Durkheim, Randall Collins argues that it is the coordination of bodily movements that leads to an intersubjectively shared emotion. Variations in emotional intensity and behaviour result from situational shift.Footnote 51

Tellingly, as Patrick Kanyangara and colleagues conceptualised, the ‘reciprocal stimulation of emotions’ in collective rituals contribute to the establishment of a general ‘emotional climate’.Footnote 52 Individual emotions, when publicly displayed in political settings, are indeed known to have a contamination effect that leads to a group sharing a common ‘emotional configuration’, reinforcing in-group affiliation.Footnote 53 Recent studies further show that increased participation in rituals is correlated with higher affiliation with the in-group.Footnote 54

Thus, rather than solely considering the social dynamics and functions of rituals, psychological approaches centring on emotions have zoomed in on what rituals do to their participants. In fact, Clifford Geertz already identified these two possible approaches to rituals, opposing purely ‘sociological’ approaches that ‘emphasize the manner in which belief and particularly ritual reinforce the traditional ties between individuals, … the way in which the social structure of a group is strengthened and perpetuated through the ritualistic or mythic symbolization of the underlying societal values upon which it rests’, to ‘social-psychological’ approaches that ‘emphasize what religion does for the individual – how it satisfies both its cognitive and affective demands for a stable, comprehensive, and coercible world, and how it enables him to maintain an inner security in the face of natural contingency’.Footnote 55 He suggested that while the first approach, discussed above, is epitomised by Durkheim, elements of the second approach could be identified in James Frazer and Bronislaw Malinowski's works. To some extent, Malinowski was the first to explore in a clear way this function of ritual as a process that alleviates the emotion of fear among its participants in situations of uncertainty.Footnote 56 Commenting on Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown, George underlined that ‘the expected, the ordered, the habitual allows life to run in sequence, conserves energy, dissipates confusion and provides an element of predictability that relieves anxiety and breeds a calm assurance that the stuff of life is under control’.Footnote 57

Psychologists have built on these classic works to study the individual level of rituals, stressing that individuals who take part in rituals indeed gain from this participation a feeling of stability and inner security in an otherwise complex and perhaps changing context. Besides their social logic, rituals have also the function of taming anxiety and reducing fear in situations of stress. In other words, they have a ‘prophylactic function’, helping individual participants ‘to get, and keep, a grip on chance, disaster, the ever-present contingency of life’.Footnote 58 For neuroscientists, ritual behaviours (from obsessive and compulsive disorders [OCD] to collective cultural performances) are the manifestation of a ‘precaution system’ aimed at reacting to inferred threats to fitness.Footnote 59 Christine H. Legare and André L. Souza locate individual participation in rituals at the heart of a ‘fundamental motive for human behavior’, the re-establishment of ‘feelings of control after experiencing uncertainty’; opening their article with a citation from Malinowski, they argue that ‘rituals … provide a means for coping with the aversive feelings associated with randomness’.Footnote 60 Under this light, OCDs, once considered as a clear pathological affection in sharp distinction with normal behaviours, are now reassessed as the pathological end of a continuum of ritualised anxiety-relieving practices. Alan Fiske and Nick Haslam brought cross-cultural evidence that OCD should indeed be understood as ‘a pathological manifestation of a normal, basic, motivated capacity that ordinary functions to integrate people into social systems’.Footnote 61 ‘Cultural rituals and OCD’, they write, ‘are characterized by a desire to produce order, regularity, boundaries, and clearly demarcated categories. In both conditions, people simplify and sharpen distinctions, focusing attention on the significance of one or two or very few aspects of the world; people dichotomize, leaving no grey area, seeking certainty.’Footnote 62 In short, individual participation in rituals brings about an illusion of control and reduces fear and anxiety, and the higher the level of anxiety felt in front of a task, the bigger the tendency to engage in ritualistic behaviours and events.Footnote 63

Another way to comprehend this function of anxiety reduction is to follow Brenda Beck's suggestion, in her comment of Scheff's 1977 theory, that rituals ‘reorient and relocus man's emotions by turning our attention outwards’.Footnote 64 Rituals relieve anxiety by bringing individuals’ attention to the procedural respect of codified practices, thereby allowing them to escape more profound questions that may exacerbate fears. At the intersection between psychology and anthropology, this line of research advances a ‘theory of ritual as a dramatic form for coping with universal emotional distress’, putting forward the idea that rituals, when correctly performed, are stereotyped ‘reenactments of situations of emotional distress’Footnote 65 whose prime function is the adequate emotional discharge of individuals in situation of collective stress. An inadequate or perturbed running of the ritual may therefore lead, in this view, to a problematic re-enactment of fear and anxiety.

Arnold Lewis's 1979 study of the impact of Sadat's famous 1977 visit to Jerusalem provides some evidence that this logic is at play in political rituals too.Footnote 66 Stressing the ritualistic character of the visit, he used the results of a poll on security-related beliefs in order to approximate a measure of the psychological effects of this event among Israeli individuals. He found that the symbol-laden visit (and the ensuing, equally protocol-heavy summit in Ismailya) dramatically decreased the feeling of insecurity in Israel in spite of its lack of tangible results towards peace, and reinforced the sense of intra- and cross-national amity.

This recognition that rituals alleviate fear and anxiety is not only important in how it explains the key mechanism behind the ‘social glue’ emphasised by sociologists and anthropologists. It also sheds light on an emotional process rarely recognised in the IR literature on emotions, which usually stresses the role of fear-, anger-, or resentment- inducing discourses or perceptions in conflict.Footnote 67

To recapitulate, the literature – first sociological and then psychological – has overwhelmingly emphasised ritual's power of integration, showing how individual feelings of security induced by the participation in a ritual, when multiplied across all participants, fuel the integration of the group at the social level. What has only recently been more fully acknowledged, however, is that there is regularly a flipside to this integrative function: rituals do also, more often than not, create social tensions and conflict. The following section situates rituals within broader social ‘occasions’ to explain this duality.

Beyond integration: The ambiguity of ritualised social occasions

Social occasions, put simply, refer to crowd gatherings events. According to Howard Becker, they are the ‘basic unit of sociological investigation’.Footnote 68 They constitute a higher form of class of individual arrangements that are shaped by a ‘sense of official proceedings’ but nonetheless remain a ‘shifting entity, necessarily evanescent, created by arrivals and killed by departures’.Footnote 69 Goffman, crucially, highlighted how particular ‘interaction orders’ are generated by particular arrangements within and across their constitutive strata: ambulatory units (that is, individuals), contacts, and conversational encounters between these units; formal meetings (ritually constrained); performances (organised around audiences and performers); and social occasions. In other words, occasions intersect with rituals and performances, a point we return to below. Like rituals, occasions can be planned and tightly executed, yet unlike rituals – but like some performances – they can be loosely arranged, directed outwards, and bring together people with many if not contradictory motivations. Building on Durkheim and W. Lloyd Warner, Goffman argues that both rituals and performances are nested within occasions, without being reducible to them.

We suggest that rituals’ potential for social and political fragmentation – or rather, their propensity to produce ambiguous outcomes in terms of integration and division – is best explained when understood as a particular instantiation of occasions. Doing so allows us to offer a broader and more dynamic and inclusive understanding of rituals that spells out their potential for division in two main ways: first it leads to a concept of ritual that is more attuned to its various components, and second because it permits a sharper conceptualisation of rituals as performances that have a range of different audiences.

Rituals and social occasions’ components: A framework

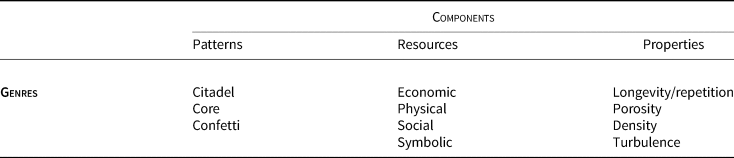

Occasions refer to three sets of components – patterns, resources, and properties – which determine how occasions – and therefore rituals – operate, on the one hand, and how they can be both studied and compared, on the other hand (Table 1).Footnote 70

Table 1. Social occasions’ components and their related genres.

Patterns refer to the spatial organisation of occasions, which shapes how interactions are conducted and has a bearing on how resources are employed. For Jonathan R. Wynn, occasions present either ‘citadel’, ‘core’, or ‘confetti’ patterns.Footnote 71 A ‘citadel’ pattern clearly demarcates the boundaries of an occasion. In such a pattern, which comes closest to the way a ritual works, participants’ identities and roles, as well as movements in space and rules of interaction are tightly specified. The wreath laying ceremony at the cenotaph in London on Remembrance Day in Great Britain exemplified this pattern, with photographs taken in different years being virtually identical. Second, a ‘core’ pattern admits more flexible arrangements, sometimes with differentiated levels of involvement. The Loyalist Parades in Northern Ireland exemplifies a core pattern: in spite of its ritualistic appearance, the largest parade is actually the result of a number of smaller parades that come together. Different parades involve different material elements such as lodge members who carry the banners that feature images of the King Williams and a handful of Protestants icons; some marches would be marked by political speeches while others proceed without but are preceded by a religious service; some marches display instruments that are associated with the parade (for example, large Lambeg drums), while others rely on bands who bring their own customised drums.Footnote 72 Third, a ‘confetti’ pattern is much more spatially scattered, though the unity of the occasion is ensured by the theme or the underlying reason of the occasion.

Attuning to the particular pattern of an occasion matters for the study of rituals because it acknowledges that some occasions might possess some ritualistic dimensions while not being fully codified. In other words, it corresponds to Ronald L. Grimes's insight that there are ‘kinds and degrees of ritualization’, rather than a binary distinction between a ritual and another type of action.Footnote 73 This is important for understanding rituals’ potentially divisive impact, because citadel, confetti, and core patterns of organisation leave the room for different types of contestation, with different types of effects. In a citadel pattern, any deviation from the strict boundaries and rules regulating the occasion will be noticed and quickly denounced by holders of the tradition. The intrusion of Extinction Rebellion militants in an already Covid-perturbed wreath laying ceremony at the London cenotaph in 2020 is a case in point: the action drew widespread outcry from across the political spectrum, from Boris Johnson calling it ‘profoundly disrespectful’, to Labour Party's Keir Starmer criticising it as ‘wrong’ and ‘profoundly disrespectful’. The storming of the US Capitol in 2021 disrupted a citadel occasion – the Electoral College vote count – to an even greater extent. This was one of the many reasons why the attack shocked Americans and raised anxiety in US society. In a core or confetti pattern, the source of potential discontent is, on the opposite, contained in its inherent flexibility, with controversial novelties and variants open to criticism (such as the inclusion/exclusion of particular participants, the modification of its timing, or the addition/removal of its prominent symbols). The backlash and ensuing division, however, is less severe than ensuing disruptions of citadel occasions, which have no embedded flexibility.

In terms of resources, occasions require, in different degrees and proportions, economic, physical, social, and symbolic resources. Physical resources provide the material basis (not the space) that supports a given occasion. Social resources include participants that animate the occasion, for example, intangible attributes such as reputation, legitimacy, and moral authority.Footnote 74 Symbolic resources concern the significant symbol upon and through which occasions draw and convey their meaning. Economic resources are the assets required for organising and running the occasion. While all occasions require at least some resources, some need little and others a lot. For example, the opening ceremony of Olympic Games demand an enormous amount of economic resources, significant social and physical ones, and is symbolically very salient, while a sit-in protest can be done with very little of each resources. In 2013, the bill of Barak Obama's swearing-in ritual rose to $170 million.Footnote 75 Here again, attuning to the differences in resources that occasions require sheds light on different sources of tensions and division. In terms of economic resources, rituals whose costs are mounting may attract attention and start to be criticised as useless – the 1977 coronation of Jean-Bedel Bokassa as ‘emperor’ of the ‘Central African Empire’ is a good example of such a drawback. The same example also shows that the question of the funding source might also cause dissent: it was not only the cost of the coronation that caused outcry and rallied opponents to the regime, but also the fact that most of the funding came from France.

In terms of symbolic resources, contestation may arise when some of the symbols used in the ritual have gained a controversial meaning within broader society, or when – in core or confetti patterns of organisation – different symbols are mobilised whose meaning clash, or when a group of participants display symbols that are negatively seen by another group of participants. There might also be contestation spurring from the type of social resources mobilised by the occasion. As evoked above, the inclusion or exclusion of particular participants might cause outrage. The way leading participants perform their tasks in the ritual can also provoke discontent: participants may be deemed insincere and cynical, or lacking dedication.

Finally, Wynn adds that occasions display varying properties, including their longevity/repetition, their porosity, their density, and their turbulence.Footnote 76 To start with, longevity and repetition answer the question ‘when and how often does the occasion occur?’ Porosity gauges the degree of accessibility to the occasion, that is, who has access? Or the access free or controlled? The density of an occasion refers to whether interaction occurring within an occasion is focused or unfocused and how long do participants maintain their attention and membership to the occasion at hand? In national reconciliation occasions such as truth and reconciliation commissions, attention is focused and prolonged. Turbulence ‘has to do with the spectrum of harmonious motivations and “disruptive activity”’.Footnote 77 Ritual is less tolerant to disruptive activity and disharmonious motivations, while performances do not require harmonious motivations and can tolerate a certain degree of disruptive activity, depending on the scale of the performance itself. Different properties of an occasion can also cause division. Chiefly, rituals with very low porosity may trigger calls to open it up and democratise it, which could in turn trigger conservative dynamics favouring the ‘tradition’. In this light, rituals can appear to be unjustifiably selective, if not directly exclusive.

In sum, conceptualising ritualisation as a continuum within the broader type of occasions allows us to locate the many different possible sources of social division of rituals. The following paragraphs show that the multiplication of audiences in an age of instant global communication, which blur the boundaries of social occasions and open them up to outside instrumentalisation, has magnified and further complexified these processes of inclusion/exclusion.

Rituals and social occasion's audiences

We have argued that a focus on occasions’ components enables us to better conceptualise the intersections and differences between ritual and performance, and thus to offer finer explanations of the role of audiences in rituals’ logic of fragmentation. To use the vocabulary proposed above, while ritual and performance involve roughly similar kinds of resources, they tend to differ in their properties. Performances exhibit a greater porosity and tolerate some level of turbulence than ritual. In the same vein, a ritual usually privileges a citadel over a confetti pattern. In contrast, neither the shape nor the effectiveness of a performance is contingent, strictly speaking, on its pattern. What matters is that the audience is enthralled by the perceived authenticity of the performers’ work. As Edmund Leach puts it, in ritual, in contrast to performances, ‘the performers and the listeners are the same people. We engage in ritual in order to transmit collective messages to ourselves.’Footnote 78 Taken seriously, this citation implies, in other words, that participants engage in a performance (not ritual) to transmit messages to the outside world.

However, our study of occasions demonstrates that this reading, fundamental as it is in much of our approach to Durkheim contribution to ritual, misses a crucial intermediation of occasion as ‘means to come a synthesis between the necessity to structuring meanings into a system [ritual] and the necessity of making those very organized meanings accessible [performance]’.Footnote 79 In this sense, we should really say ‘ritual performance’, which would imply that actors do both – that is, they transmit messages to themselves and to the world. Uncertainties arise, however, as success inside does not necessary lead to success outside. In other words, it is important to note that rituals have – increasingly so – multiple audiences beyond their direct participants,Footnote 80 and thus also have a logic of representation. In an age of instant and global communications, their components – patterns, resources, and properties – and mise-en-scène are seen, and sometimes intensely scrutinised, by multiple audiences. Therefore, the probability for each of the different potential sources of fragmentation listed above multiplies. This aspect of rituals has so far mostly been emphasised by Jeffrey Alexander, who defines them as a ‘cultural performance’, that is, a ‘social process by which actors display for others the meaning of their social situation’.Footnote 81 ‘All ritual’, he adds, ‘has at its core a performative act’, whereby ‘meaning is projected from performance to audience’.Footnote 82 Here, we expand this idea by distinguishing rituals’ various audiences and participants, and by clarifying how this multiplicity is crucial when it comes to explaining fragmentation.

While the type of rituals described by the classic literature were those in which most if not all the relevant in-group participated, in the digital age more and more rituals have an important non-participating audience, to which a certain message is projected. But this approach, rather than departing from Durkheim's, actually plunges its roots in Durkheimian understanding of rituals as it relates to drama. In fact, Alexander (whose work has contributed to a renewed interest in Durkheim's thought) tends to overlook the latter's distinctive influence on performance.Footnote 83 While the relation between ritual's function and drama's effects remains contested, we propose a reading of Durkheim that recognises the dramatic features inherent in Durkheim's treatment of ritual performative effects. Indeed, according to Durkheim, performances represent the articulation of thought and action.Footnote 84 In general, the way in which ritual and performance intersect is pitched in a rather convoluted language. This could account if in part for why that relation sits out of most researchers’ radars.Footnote 85 Ritual meets performance through dramatisation. For Durkheim, ritual dramatises beliefs; and, it is through the dramatisation of beliefs that representations become explicit and available to both ritual's participants and audiences. In this perspective, ritual is not only a means of communication and integration, but also a symbolic and aesthetic activity. This is clearly expressed in Durkheim's study of commemorations. He argues that the ritual of commemoration ‘involves remembering the past and making it present … by means of a true dramatic performance’. It is, in short, about ‘actors playing roles’.Footnote 86 In other words, ritual performance appear as ‘occasions where actors play, settings are ready for performance to be made, and audiences to participate actively in ritual action’.Footnote 87 That is, the performance of ritual challenges the internal structure of ritual as its symbolic effectiveness is no longer exclusively dependent upon participants’ following a series of ritually bounded rules but increasingly reliant upon whether symbols acted out generate effects beyond the in-group participants.

However, what Durkheim did not anticipate is the fragmentation of audiences in the contemporary world, where ‘affective communities’ are increasingly transnationalFootnote 88 and information circulates globally in seconds. As performance has to address multiple audiences, it can therefore only achieve its effects if it is perceived as authentic, that is, an uncontrived activity by its addressees. Yet, performance steps out of ritual's bounds as soon as it becomes unable to seamlessly unify the different audiences.Footnote 89 In the following paragraphs, we identify the various audiences of today's rituals, and explain what their presence means for the logics integration and fragmentation. Figure 1 below visually represents these audiences.

Figure 1. Rituals’ multiple audiences.

There are, first the individuals directly taking part in the ritual, and, just beyond, the broader ‘in-group’, that is, the directly ‘observing audience, the relevant community at large’.Footnote 90 In many contemporary political rituals such as those described in the next section, the relevant in-group is indeed much larger than the participating members: media coverage allow absent members to follow the ritual and potentially ‘project themselves into the characters they see onstage’.Footnote 91 The aesthetic components of the ritual take a particular importance in this process: clearly displayed symbols are crucial in conveying this meaning to the external audience, as is the particular location of the ritual: both symbols and location ‘make vivid the invisible motives and morals they are trying to represent’.Footnote 92 Rituals, in this sense, come close to the theatricality, understood as a performance where ‘a network of many types of signs which, in addition to words, include body language, costumes, sets, lights, colours, props, intonations, etc.’Footnote 93 have exaggerated traits to make sure that the audience clearly receives the overall narrative and message conveyed by the play. As such, rituals operate a function of condensation whereby ‘an extremely complex and complicated reality is compressed’.Footnote 94 Potentially, a well-executed ritual can therefore today expand both its logics of integration to very large populations. The examples examined below confirm that the relevant in-group potentially counts in the hundreds of millions, spanning across national boundaries. In other words, this relevant community is, increasingly, multiple, heightening the potential for contestation of the ritual's components (in Figure 1 above, we highlight this dimension by drawing boundaries within the in-group). As Alexander argued, contemporary societies are much more fragmented than the kind of societies studied by Frazer, Malinowski, and others, and as a result while the latent social function of rituals is still integration, in today's societies their goal is more to ‘re-fuse’ a plural population across cleavages and differing worldviews.

It is in this context that the performance character of rituals becomes increasingly important: ‘the emergence of more segmented, complex, and stratified societies created the conditions – and even the necessity – for transforming rituals into performances’.Footnote 95 Here therefore lays a fundamental risk of contemporary rituals: that they do not achieve such a re-fusion, that they merely appear relevant to this or that particular group within the broader community. Four issues related to the patterns, properties, and resources of social occasions can produce this problem. First, the symbolic resources and chosen location can be seen by some as too clearly attached to one particular subpopulation of the in-group, or have become divisive, and hence do not crystallise the broader community. Consider how hotly contested the American flag and anthem – quintessential symbols of American unity – have become when displayed in pre-match ceremonials in the US,Footnote 96 or how many Trump supporters turned the US capitol into a symbol of the Washington ‘swamp’ rather than that of American democracy. Second, some key components of a ritual usually performed to fuse an in-group can be deliberately distorted or mispracticed. Nancy Pelosi's shredding of the folder containing Donald Trump's 2020 State of the Union, at the end of this highly codified, ‘citadel’ address, is a case of deliberately derailing this ritual's symbolism; it was thus overwhelmingly understood as a defiant, polarising act that not only revealed division within US society but further established it. This was especially so because of both Pelosi's key position of power in the ritual (one of its main characters, her behaviour was especially codified) and the live retransmission of the event in multiple media. Third, it may be that the main actors leading the ritual do not look authentic and sincere to parts of the in-group, who may interpret their performance as evidence of manipulation.Footnote 97 When the logic of representation fails, tensions, rather than communion, may characterise society. Fourth, some communities of the in-group may feel excluded by a ritual, especially if its pattern remains unchanged and thus potentially echoes old systems of domination. Parliamentary work – a highly ritualised occasion as Rai showedFootnote 98 – is, for example, recurrently criticised by people who stress their lack of ethnic diversity or their embedded sexism.

A second, more distant audience is now crucial when evaluating rituals’ logic of fragmentation, and especially when it comes to understanding that they can both at once foster integration and trigger fragmentation: the out-groups.Footnote 99 In fact, carrying out a ritual often implicitly or explicitly recalls the existence of a non-participating Other, and the strengthening of in-group cohesion around a set of core values identified as essentially associated with the community has the side effect of sharpening boundaries with out-groups. The broadcast of a ritual may, in certain circumstances, fuel a perception, among some out-groups, that the group involved in the ritual is actively excluding them, or even provoking them. For instance, the Orange Order's ‘walking season’ in Ireland is directly perceived by the Catholics as a provocation. When rituals are broadcasted outside the boundaries of their relevant groups, they can exacerbate negative emotions and tensions as they are strategically framed by political leaders in specific ways that encourage their supporters to interpret them as a hostile event.Footnote 100 Note how in such instances, the ritual produces division between two groups by further integrating each one separately. IS propagandists’ recurring depiction of Shi'a rituals as ‘evidence’ of a threatening, inherently corrupt enemy, is a sharp example: it fuels both at once the integrative logic of ISIS members’ community and the fragmentation logic between the Shi'a and Sunni branches of the Muslims faith. The ceremonial visits of prominent Japanese politicians at the Yasukuni Shrine is another prominent example of how a single ritual can simultaneously unify an in-group (although the Japanese population and political elite is increasingly divided on the issue) and alienate an out-group, chiefly the Chinese.Footnote 101

Yet as displayed in Figure 1, the out-group is not uniform: some out-groups may see the ritual in a favourable way (or ignore it altogether) while others may perceive it as offensive. Most communities across the world simply don't notice when a Japanese prime minister visit the Yasakuni Shrine, whereas such a move is instantly debated and generally opposed in China, a rejection more often than not fuelled by political leaders’ rhetoric and display of negative emotions.

Post-terror rituals, between integration and fragmentation

The current section mobilises our theoretical framework in order to analyse the integration-fragmentation dynamics that accompany the ritualised social occasions that tend to follow acts of extreme political aggression like terrorist attacks (declarations of war are another example). While ritual is ‘one of the oldest and most resilient responses to death’,Footnote 102 what we could call ‘terror rituals’ have been surprisingly understudied. In fact, ‘even within the domains of ethnography and ritual studies, disaster rituals hardly receive any attention’.Footnote 103 This is surprising given the importance of rituals in times of high uncertainly or challenges to the social order. Indeed as Fiske and Haslam argue, ‘people tend to carry out collective cultural rituals to create or restore order, particularly when the normative order is threatened or problematic’. A significant research agenda focusing on post-terror rituals does actually exist in psychology, yet it almost exclusively focuses on individual reactions to such incidents, measuring people's resilience through a range of indicators (for example, PTSD symptoms). A social study of post-attack rituals remains to be done, as acknowledged by psychologists themselves, who recognise that ‘massive disasters are inherently cross-scale in their impact, disrupting functioning across multiple levels of the interdependent socio-cultural systems in which individual human lives are embedded’.Footnote 104

By applying our theoretical framework for the study of rituals to this case, we therefore considerably expand the analytical lens beyond the individual level, incidentally providing explanations for surprising phenomena observed but unexplained by psychologists, such as the unexpectedly low level of psychological trauma in places that experienced large-scale terrorist attacks.Footnote 105 Bill Durodié and Simon Wessely hinted at the importance of post-attacks rituals when they suggested that there is a ‘need for approaches that clarifies people's values rather than emphasising their vulnerabilities’,Footnote 106 but did not offer more specification. Samuel Merrill and colleagues’ exploration of the ‘commemorative public atmosphere’ that followed the 2017 Manchester Arena bombing constitutes the initial exploration that we seek to complement.Footnote 107

To study terror rituals, we examine how the dual dynamics of integration and division unpacked above played out in aftermath of two different terrorist attacks. The first case we consider is Anders Behring Breivik's bombing in Oslo and mass killing in Utøya on 22 July 2011. The attack was followed by a range of ritualised social occasions, with one main event standing out: the ‘flower march’ that gathered over 200,000 participants in Oslo on 25 July.Footnote 108 The second case investigated is the Charlie Hebdo shooting that shook Paris in January 2015 (with the subsequent Hypercacher supermarket attack). We focus on the ‘Republican marches’ that followed the attacks, which gathered more than three million participants across France, and tens of thousands in demonstrations abroad (20,000 in Brussels, 18,000 in Berlin, 12000 in Vienna, etc.).

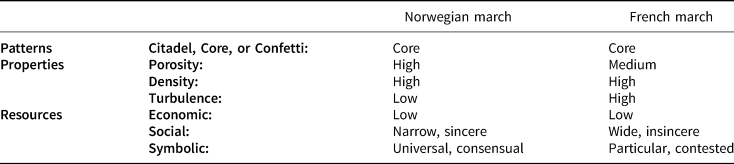

At first sight, these two cases share important similarities and therefore appear to be ‘most similar’ cases: they were both marches, they were massively attended by participants holding messages enunciating important group values, each had its central, highly visible symbol (the flower in Norway and the stylised ‘Je Suis Charlie’ motto in France), etc. A traditional analysis of ritual focusing solely on their integrative function would thus fail to see and understand the different outcomes, in terms of social integration and fragmentation, that these two similar cases actually produced. Systematically attuning to the various theoretical dimensions teased out above, in contrast, allows us to explain why the French march triggered more fragmentation than the Norwegian one, which were more successful in realising their integrative function. The following paragraphs explore these dimensions summarised below in Table 2, with an appreciation of how the multiplicity of audiences impacted them.

Table 2. Comparing two ritual occasions.

In terms of their patterns, none of the marches were heavily regulated; roles and sequences were not rigidly set and implemented. The commemorative events that were organised in the days after the marches – for instance, the ceremonies accompanying the inaugurations of the commemorative plaque in Paris – were much more akin to the citadel pattern, with ‘the official uniforms, the formal lines of politicians, the stiff choreography of the state-led act of remembrance’.Footnote 109 However, despite their seemingly organic nature, the marches did have an organisation, with a timing, predetermined places where the march would stop, and prominent symbols to be displayed by participants. For that reason, they can be positioned as core social occasions, with important but flexible ritualistic patterns

As a result, we suggest that the marches played a role in the strengthening of social integration measured in their aftermath. There is no direct study of individual participants’ emotions and sense of security,Footnote 110 but testimonials abound to show that participants in Paris and Oslo bonded through the collective feeling and display of sadness, anger, defiance and fear. People marched slowly together, and countless displays of unity have been observed (hugs, hand-holding, singing in unison, etc.) over several hours: the density of the rituals was high in both cases. The BBC correspondent in Oslo observed that participants ‘stood quietly in contemplation, many with tears in their eyes, or they hugged their companions and offered consoling words’.Footnote 111 For Ida Marie Høeg, the collective display of these emotions, ‘triggered by the March and expressed in the March’, were crucial in ‘shaping identity and community’: ‘participation in the rose March elicited strong feelings of belonging, meaning belonging to a community of “we” – Norwegians, a people or a nation’.Footnote 112 Political leaders publicly expressed the same emotions, reinforcing the self-evidence of the consensus around the situation.Footnote 113 Dag Wollebæk and colleagues measured an increase, among Norwegians, in societal trust and civic engagement in their aftermath,Footnote 114 while Moa Eriksson's analysis of the Norwegian Twittersphere showed a pattern of national unification.Footnote 115 Mette Andersson further explains that the flower march marked the beginning of a declared twenty-day period of ‘civil peace’ (‘borgfred’), wherein public political debate on controversial themes related to immigration were deterred.Footnote 116

However, the same integrative result has not been evidenced in France, certainly not with such strength – this, we argue, can partially be explained by the differences in properties and resources between the two rituals. Marches had a high porosity, meaning that anyone could, a priori, join and participate – this stands in contrast, again, to the later commemorative ceremonies evoked above, which in France were ‘all hermetically sealed by the strict security structures’ and rejecting ‘many of the public who had hoped to attend’.Footnote 117 Both marches attracted large numbers of attendees, however the French march was not characterised by full porosity. Indeed various categories of people – either far-right or Salafist groups and individuals – had been told loud and clear that they were not welcome. Most prominently, National Front leader Marine Le Pen was warned not to attend, creating tensions and divisions within the French society even before the event as to who was the strongest guarantor of Frances’ republic and ‘laïcité’. As a result, several excluded groups like the National Front organised separate demonstrations in local strongholds outside Paris, but largely using the same banners seen in the main march: the degree of turbulence was significantly higher in France than in Norway, from the onset. Because of this semi-open porosity, the French ritual and the values it was supposed to demonstrate were, before it even begun, openly and vividly contested; the integrative function of the French marches was unlikely to be fully achieved.

As far as resources are concerned, significant differences can be observed that further explain the more ambiguous effect, in terms of integration and fragmentation, of the French march. Taking social resources first, both marches were characterised by a line of political leaders occupying a visible position at the front (see Figure 2). However, the French case was immediately marked by a second controversy on top of the one related to the absence of Marine Le Pen. While in Norway political leaders’ participation was widely perceived as authentic and homogenous, the Paris march was fronted by a composite assemblage of numerous political leaders, which was immediately perceived as at odds with the values condensed in the ritual. Over forty top foreign officials were invited to walk alongside Francois Hollande, and even if this was an attempt to display universal unity beyond France, unease quickly emerged about the participation and authenticity of some. Representatives from core Western states and institutions were not criticised as they somehow represented the relevant in-group (for example, Angela Merkel for Germany, Jens Stoltenberg for NATO, Martin Shulz, Donald Tusk, Federica Mogherini, and Jean-Paul Junker representing the EU), but the presence of leaders with problematic records in terms of freedom of speech and political liberties, like Gabon's Ali Bongo, Jordania's King Abdullah, Turkey's Ahmed Davutoglu, and Hungary's Viktor Orban, was immediately and widely condemned, far beyond France,Footnote 118 casting doubt on the nature of the in-group involved in the ritual and its values.

Figure 2. Political elites standing together in frontline positions at the Paris (left); and Oslo (right) marches.

Similarly, while symbolic resources were apparently similar in both marches, key differences explain the more ambiguous social effect of the French ritual. Both marches similarly took the form of a ‘ritual pilgrimage’ where a ‘physical and digital journey [is made] to places of high symbolic value’Footnote 119 (the Oslo city hall in Norway, the Place de la République with the Marianne statue, and the Place de la Nation in Paris), and in both cases instructions circulated encouraging participants to refrain from using slogans or logos from organisations and political parties. In Norway and France, one single symbol was used, condensing its message and values (see Figure 3). In Oslo, the initial idea was to hold roses but instructions were later given to bring all kinds of flowers to avoid associating the march with the sole Labour party (from which most victims in Utøya were members), in an attempt to have a more universal and less easily reappropriated symbol. These different flowers were understood to symbolise peace, love, life, and beauty in plurality. In France, the ‘Je Suis Charlie’ board became an instant icon symbolising freedom of expression:Footnote 120 ‘images were produced by professional and ordinary media users alike and followed a repetitive pattern of symbolic communication, crystallised around the message “Je suis Charlie”’.Footnote 121 However, while the Oslo symbol was hardly contestable (especially after the call to bring all types of flowers), the French symbol rapidly became controversial, with various segments of the in-group understanding its meaning differently and other ones directly criticising it. Even one of the surviving members of the magazine openly criticised the symbolism of the march, lamenting that the magazine had become a political symbol whereas the magazine's ethos was precisely to reject and criticise political ceremonials.Footnote 122 The ‘Je Suis Charlie’ symbol itself became the source of many twists and distortions whose aims were to affirm different sub-identities (for example, ‘Je Suis Flic’, visible in Figure 3), or to oppose the supremacy of the values of freedom of expression and ‘laïcité’ (for example, ‘Je Ne Suis Pas Charlie’, ‘Je Suis Ahmed’). Massimo Leone observed that ‘just hours after the shocking news, stereotypical patterns of interpretations were arising’, including already a range of contestation and challenges to the ‘Je Suis Charlie’ symbol as well as to the central message condensed and projected by the march.Footnote 123 At the same time it united a broad range of in-group members, the ‘Je Suis Charlie’ symbol thus at the same time became the sources of social divisions. Within a few weeks, these divisions became the subject of intense discussions in the media as well as within academic milieus, which were further intensified when sociologist Emmanuel Todd published a study arguing that most participants were characterised not by a commitment to freedom and liberty but by anti-Muslim attitudes.Footnote 124 This intervention fuelled more debates, each aggravating the fragmenting effect of the ritual.Footnote 125 In contrast to Norway, where discussions on social media showed a pattern of support for unity,Footnote 126 similar studies of the French situation have revealed that polarising and politicised debates quickly replaced emotional expressions of shock and mourning.Footnote 127

Figure 3. A single unifying symbol in Oslo (flowers, left); and Paris (‘Je Suis Charlie’ boards, right).

This ambiguity of the French symbol was accentuated through the remote presence of external audiences sometimes far from the French or even ‘Western’ in-groups. In the case of the Oslo march, the generic and symbol of the flower, together with its near-universal and consensual meaning, made the march an easily understood and hardly contestable collective ritual of mourning, more than a political ritual. In contrast, the underlying message and values conveyed by the French marches, with a symbol stressing freedom of expression and explicitly mentioning a magazine whose aim was to provoke public opinion and break taboos, made it a political ritual more than a mourning one, which would inevitably be opposed by a range of out-groups. The French debate amplified to multiple external audiences via traditional and social media, which simultaneously intensified the ‘mourning and commemoration, as well as ritual contestation’.Footnote 128 As a result, the march ‘suddenly “belonged” to a far vaster population than that of France alone, given the global “reaching out” that the attacks provoked’,Footnote 129 and while many sensed grief and compassion, others felt insulted and provoked, especially after Charlie Hebdo republished, in an act of defiance, its caricatures of Mohammed less than one week after the attack. Two weeks after the march, no less than 150 attacks on French citizens and companies had been carried out in countries of Muslim majority.Footnote 130

Thus, even though the Norwegian and French marches seemed remarkably similar, a closer look at their patterns, properties, and resources, allowed by an understanding of rituals as social occasions, as well as a consideration for today's multiplication of audiences beyond the in-group, enabled us to better understand the significant difference in their respective power of integration and fragmentation. In this perspective, we may draw the following (theoretical) lessons from the discussion. The Durkheimian view that fuses individual entities into a collective consciousness assumes that rituals ride on one unique repertoire, namely harmony/solidarity.Footnote 131 Or, put in different words, ritual is ‘congruent with … a magical imitation of desired ends, a translation of emotions, a symbolic acting out of ideas, a dramatization of text’.Footnote 132 However, recent research on the performance articulation of rituals tend to confirm that ‘ritual gains force where incongruence is perceived and thought about’.Footnote 133 That is, the workings of ritual occasions take place wherein the incongruity between the actual world and the world of ritual meet. Ritual occasions therefore entertains a tension with the non-ritual world. In the articulatory performance of both Oslo and Paris marches, then, ritual occasions aimed to create a ‘subjunctive’ order, an order ‘as if it were truly the case’.Footnote 134 That is, order and unity must not just be meted out; they must be seen to be meted out.Footnote 135 As Durkheim puts it, in ritual, people ‘forget the real world so as to transport them into another where imagination is more at home’.Footnote 136 Yet, here lies the precarious nature of ritual: the shared world it establishes is subjunctive (as if); it is illusory (though participants might be oriented towards it as if it were real). It is not coincidental that the fragmented and plural experience of daily experience haunts ritual as if world, as it vividly did in France. The overt tension between the subjunctive world of ritual and the world of lived daily experience calls for a focus on the actual workings of rituals, whose ambiguous repertoires a performance approach to ritual discloses.

Conclusion

One of the perennial assumptions of a Durkheimian understanding of ritual is that ritual is meant to regulate and stabilise social life, create harmony, and restore unity after disruptions.Footnote 137 Our aim in this article has been to offer a framework that shows that such a view neglects the fundamental tension between the world rituals attempt to carve out and the world of everyday experience. To do so, we have attempted to display and locate the sources of the multiple configurations of social fragmentation and integration that can emerge from rituals, in a way that pulls together the many observations recently made by scholars stressing the disintegrative dimension of rituals and connects them with the classic Durkheimian stance. In other words, we showed how an encounter between ritual, performance, and occasions holds out a genuine possibility for theorising the ambiguities inherent in rituals’ repertoires. Ritual occasions instantiate ‘could be’ worlds where members of a society congregate as symbol users. In this perspective, the individual experiences of insecurity and disorder can only be turned into collective security and order through a ritual act of ‘as if’. This means two things, which indicate the boundaries of the world created by rituals. First, the world created by rituals is temporary; a ritual has both a clearly demarcated beginning and an end. Thus, the world of disorder and insecurity was only provisionally bracketed by the Oslo's or the Paris's rituals. Second, participation in a ritual marks acceptance of the relationship that the ritual is an index of and draws the recognised boundaries of empathy. This was, we have seen, a key difference between Oslo's and Paris’ ritual occasions.

While the symbolic resources they mustered varied (flowers in Oslo and ‘Je suis Charlie’ in Paris), the two marches shared a similar ‘core’ pattern with flexible organisation and different levels of engagement. However, this core pattern accommodated a high degree of porosity and density in the Oslo case whereas the Paris ritual occasion exhibited more turbulence: some actors were barred from joining the march while other self-excluded themselves. In other words, the spectrum of ‘disruptive activity’ was wider in Paris than in Oslo; this appears in the dissenting voices’ claims that the world produced by the Paris march was not the real world of France, that is, a world torn by religious, social, and ethnic fractures.Footnote 138

Seen thus, our article has sought to show how ritual occasions in general, and terror rituals specifically ‘involve developing repertoires [of feelings and orientations] that operate in complex interplay with the world of everyday experience’.Footnote 139 However, while ritual occasions would attempt to leave a trace on the mundane world, the two do not merge. This, of course, tells us something important about what is ultimately at stake in ritual occasions: rituals do not primarily express a worldview of harmony; rather, it points to a share subjunctive world which never manages to commit actors to behave as it demands, beyond the exigencies of a given ritual occasion. Therefore, our article suggests that disaster rituals aim to ‘reconfigure the fabric of sensory experience’ by staging the political ‘distribution of the sensible’.Footnote 140 We acknowledge that the productivity of our logics of integration and security lies in the ritual's capacity to coordinate different experiences. But when disaster ceremonies assume a logic of performance, they expose the fundamental tension between presence and representation. In this way, the root of ambiguities that underlie disaster ceremonies is not that they pursue different functions – it is that they wish to animate two worlds in one.Footnote 141

Acknowledgements

Various iterations of this article were presented at seminars and conferences, including St Andrews and Exeter in 2014, and at the 2019 ISA Annual Convention. We are grateful for the comments we received from participants and numerous discussants and chairs, in particular Lene Hansen, K. M. Fierke, Faye Donnelly, Merje Kuus, Lene Hansen, Shirin Rai, Ted Hopf, John Heathershaw, and Gregorio Bettiza. We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their engaging reading of the articles and very thoughtful comments, as well as the RIS editors for their work and guidance throughout the review process.