1. INTRODUCTION: WOMEN'S WAGES AND HOUSEHOLD ECONOMIES IN THE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURIES

Across Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, nursing and child-rearing were to a large extent a wage activity. The occupation created two markets: one for wet nurses who worked for individual families (either in their own houses or in the houses of the children they raised) with relatively good work conditions and high wages, and one for wet nurses who worked for foundling hospitals as «externals», taking children into their own houses, generally in the countryside. We look at the latter group in this article, which shows the extraordinary magnitude of the occupation for two centuries and how it became a vital source of income for the households of wet nurses and for the rural and urban economies from which they came.

Studies of historic wages have been the object of renewed interest in recent years. An important advance is the recognition that the wages of adult men cannot be taken as an indicator of household income. First, because the majority of men had insufficient annual income to support their families, even if they contributed their total income. Second, because many homes were not headed by men. Third, because we have more and more evidence of the importance of women and children's wages to the household economy.

Women's wages are critical to two main debates for explaining how economic growth came about: whether such wages grew enough to incentivise mechanisation and thus light the fuse of the industrial revolution; and whether they acted as an incentive to delay marriage and thus explain the decline in fertility that laid the foundations for modern society.Footnote 1

With regards to the first debate, the thesis of the «high wage economy», argued by Robert Allen, affirms that the industrial revolution occurred first in England because the high costs of labour (relative to capital and energy) created incentives for labour-saving technology—in the first place, the spinning jenny, which replaced the work of women spinners. Allen's thesis is founded on the work, among others, of Muldrew (Reference Muldrew2012), which pointed out the increasing wages of women spinners. Other authors have contested this thesis: for Humphries and Weisdorf (Reference Humphries and Weisdorf2015) and Humphries and Schneider (Reference Humphries and Schneider2019), hand spinning was a very poorly remunerated occupation. Mechanisation—and especially the development of the factory—would have been «motivated by the desire to use cheaper child and female labor in a way that ensured discipline and quality control» (Humphries and Schneider Reference Humphries and Schneider2019, p. 128). This debate has generated demand for women's wage series to support one or the other position and has exposed shortcomings in the literature regarding the topic.

Regarding the second debate, De Moor and Van Zanden (Reference De Moor and Van Zanden2010) argue that women's employment, especially in domestic service, is associated with a delay in marriage age and a decline in the number of children. The «northern European marriage pattern», already pointed out by Hajnal (Reference Hajnal, Eversley and Glass1965) and also recently identified in southern European countries (Ribeiro da Silva and Carvalhal Reference Ribeiro da Silva and Carvalhal2020), would imply an increase in wages and a stimulus for growth. Horrell et al. (Reference Horrell, Humphries and Weisdorf2020) have qualified the model, showing that women delayed their marriage age—therefore lowering their fertility—when their own wages rose, even if men's wages also rose.

This article is a contribution to the debate on the role of women's wages in preindustrial economies. It focuses on a little-known occupation, that of wet nurses who worked for foundling hospitals as «externals» and who were mainly married women in rural localities.Footnote 2 Until now, these wages have been ignored, but they must be taken into account in order to understand the economy, especially the rural economy, in the 18th and 19th centuries. Thus, this article adds to the study of women's work, wages, occupational structure, pluriactivity, the service sector, the benevolence system, family incomes, standards of living and the peasantry. Furthermore, it presents new sources and new analytic methods for studying women's labour and wages during these two centuries.

To learn the income of peasants in the 18th and 19th centuries, we already have numerous studies on agricultural day wages. With respect to non-agricultural day wages, most of the available series are for construction workers (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1988; Reher and Ballesteros Reference Reher and Ballesteros1993; Lanza García Reference Lanza García1998; Andrés Ucendo and Lanza García Reference Andrés Ucendo and Lanza García2014, Reference Andrés Ucendo and Lanza García2020; García-Zúñiga and López Losa Reference García-Zúñiga and López Losa2021; López-Losa and Piquero Zarauz Reference López Losa and Piquero Zarauz2021). There are also studies of the service sector, including workers in municipal services (Reher and Ballesteros Reference Reher and Ballesteros1993), and charitable institutions (Llopis Agelán and García Montero Reference Llopis Agelán and García Montero2011).

Day wages in agriculture and construction, the most representative sectors by number of workers, were only available during certain months of the year—for agriculture, local crops determined the working year; for construction, weather limited the working year to about 225 days (Llopis Agelán and García Montero Reference Llopis Agelán and García Montero2011, p. 299). According to all calculations, these day wages were insufficient to maintain a family, as the Comisión de Reformas Sociales concluded (1891).

This makes clear, therefore, that peasant families had access to income other than the agricultural day wages of adult men during certain months of the year and, if they owned land and cattle, other than their own agricultural production. One of the explanations for the growth of the rural population is that peasants dedicated part of the year to the transport and the sale of goods, to manufactures and to the extraction and transport of minerals. The decline of these activities, from the mid-19th century, signalled the beginning of the rural exodus. Despite the explanatory importance given to these non-agricultural activities, there are few studies that systematically analyse them, and even fewer that ask what portion of family income in the 18th and 19th centuries came from non-agricultural activities. To a large degree, this gap is due to the fact that such activities were mainly carried out by women (Hernández Reference Hernández García2013; Sarasúa Reference Sarasúa2019).

2. WET NURSES OF FOUNDLING HOSPITALS IN EUROPE AND HISPANIC AMERICA

Infanticide, condemned by all religions, becomes abandonment, a permitted practice, thanks to the appearance of institutions that took in children, thus avoiding (or at least delaying) the children's death. With the emergence of these institutions, a new and pressing problem arose; that of how to feed the children. Attempts to feed them animal milk failed—or were impossible to implement where foundlings numbered in the hundreds—so the simplest, cheapest and fastest option was to find women who would raise them. Unlike the private demand for wet nurses, the institutional demand for women to nurse foundlings was not shaped by ideas about the best methods for feeding children.

There is abundant literature on foundlings and paid wet-nursing in Europe, where foundling hospitals existed in all countries, though earlier and more extensively in the Catholic countries. The practice of abandonment and the institution of foundling hospitals have been studied by demographers explaining the evolution of child mortality and, in recent years, by historians of public assistance and diet.Footnote 3

Our focus is the wet nurses who worked for foundling hospitals. We know little about these women, but we can identify certain common features found in the studies of paid wet-nursing in Europe. First, foundling hospitals mainly sought rural women to nurse and raise abandoned children. Studying the organisation of wet-nursing at the Foundling Hospital of London, founded in 1741, Fildes describes paid wet-nursing as a specialisation of certain rural zones—a «cottage industry» whose contribution to the rural economy was similar to that of rural manufactures (Reference Fildes1988). In northern Europe the situation was similar. At the foundling hospital of St. Petersburg, founded in 1770:

The foundlings were usually nursed for six weeks at the home in St Petersburg before being brought by the peasant women to their homes in the countryside, where they remained until the age of ten or longer. The remuneration decreased when the child was old enough to take part in the work of the farm. Wet-nursing developed into an integral part of the economy on the Karelian isthmus. Poor families in particular saw this as a way of supplementing their meagre income with cash or credit notes which could be traded or cashed in St Petersburg … Farmers on the isthmus … considered the foundling home a good source of extra income. (Moring Reference Moring1998, pp. 188, 190)

A second common element for most foundling hospitals was the chronic insufficiency of funds to pay the wages of wet nurses—a shortfall that was exacerbated at certain moments—and the relationship between underfunding and the mortality of foundlings.

To understand the role that the occupation and its wages had for wet-nurse households, it is important to note that the job was not just breastfeeding. Between breastfeeding, which normally lasted until the age of 18 months, and the readmission of the children who survived back into the hospitals, there was a period of upbringing that could be carried out by non-lactating women, that is, by all women. The wages of these «dry» or «weaning» wet nurses were less than those for breastfeeding, but the work let women care for several children at once, which would allow many, especially widows, to survive.

A last feature that seems to have existed in all countries was the phenomenon of geographic specialisation (also a characteristic of the market for wet nurses for individual families). Although women raised foundlings in all regions and provinces, they were concentrated in certain regions and, within these regions, within concrete localities where the existence of family networks, good communication with cities (e.g. by railroad) and weak labour demand for alternative occupations resulted in a wet-nursing specialisation, which might continue for generations. Regarding this territorial distribution of wet nurses, the literature agrees on the impact that the Napoleonic Wars had on much of Europe during the first decades of the 19th century. The conflict interrupted communications and isolated rural districts. The flow of wet nurses travelling to cities to pick up foundlings and collect wages was disrupted, and, consequently, child mortality rose.

At the initiative of civil and ecclesiastical authorities, foundling hospitals were also established throughout Spanish America. Bishop Gerónimo Valdés founded the Real Casa Cuna in Havana in 1711 (Torres Pico Reference Torres Pico2013). The hospital of Santiago, Chile, was founded in 1758 (Milanich Reference Milanich2001, p. 79). In 1766, the enlightened Archbishop Lorenzana founded the hospital of Mexico City, though the San Cristóbal Hospital for Foundling Children had existed in Puebla since 1604 (Gonzalbo Aizpuru Reference Gonzalbo Aizpuru1982). The hospital of Buenos Aires was established in 1779 and in its first 10 years received 685 children (Moreno Reference Moreno2000, p. 667). With a city population of 55,416 in 1822 and an average of 2,834 baptisms each year, foundling admittance in Buenos Aires constituted 5 per cent of annual births (Moreno Reference Moreno2000, p. 673). During the 1880s, the hospital of Santiago supervised more than a thousand children per year, of which 800 were assigned to external wet nurses. «In 1900, the enormous figure of 2,300 foundlings was reached, which is to say, one out of ten children born in Santiago at the end of the century was sent to the Hospital for Orphans» (Milanich Reference Milanich2001, p. 82). As in Europe, foundling hospitals in Spanish America depended on a vast network of wet nurses «composed of poor women who sometimes lived in the city but mainly were dependents of the large estates around the capital» (Milanich Reference Milanich2001, p. 91).

3. FOUNDLING HOSPITALS AS LARGE PUBLIC SERVICE COMPANIES

Foundling hospitals, along with hospitals and hospices, formed a network of charitable institutions of the old regime that would be maintained as a central piece of liberal benevolence. They were typically urban establishments, founded at the initiative of kings, the church or civil benefactors. They were managed by a staff of employees (accountant, treasurer, doorman, chaplain, in-house wet nurses and senior nurse, cooks, midwives, doctors and nuns) and directed by ecclesiastical leaders, upper-level members of the administration, or, in some cases, by women from local elites who, beginning in the mid-18th century, identified with enlightened reforms. The hospitals received children who were found, delivered, placed in the cradle winch or brought from women's prisons or from medical hospitals, where their mothers had died or were interned. At the age of six or seven, the children who survived were sent to another institution, the hospice, where, following an itinerary designed to turn them into useful citizens of the state, they learned a profession such as maid, seamstress, artisan, farmworker or soldier.

The first institutions specifically for foundlings appeared in the 15th century, with the formation of hospitals such as Santa Creu in Barcelona in 1401 and Santa Cruz in Toledo in 1499. Church initiative came together with the modern state when the Catholic monarchs established the Royal Hospital of Santiago de Compostela in 1492.

We have taken as foundling hospitals those centres that received foundlings (often with «winches and bells»), whose main objective was avoiding infanticide, and which organised their own systems of wet-nursing. These hospitals initially depended on ecclesiastical or civil administrations. Later, in the 19th century, they would become part of the national benevolence system, funded by municipal, provincial or national budgets. Towns contributed to the costs of the hospitals that took in their children—a fixed amount per citizen or for each child sent—by means of dedicated taxes (e.g. on the consumption of wine). In cities, extra revenues to support the hospitals came from leisure activities (such as bullfights and theatre), raffles and annual charity drives.

Throughout Europe, the 18th century saw a surge in the creation of foundling hospitals. Their creation, however, was not equalled by the provision of resources, especially taking into account the period's inflation, which rapidly lowered the real wages of wet nurses, just when the increase in foundlings demanded an increase in wet-nurse recruitment. Good enlightenment intentions collided with the crisis of the treasury, which would sacrifice, in the first place, benevolence.

In the first half of the 19th century, the benevolence system underwent a long period of upheaval, caused first by the War of Independence (after the invasion of the Napoleonic army) and later by a confluence of financial and institutional factors. Aware of the insufficiency of public resources in support of the system, the liberals who enacted the General Law of Benevolence in 1822 recommended turning to the Sisters of Charity (who had arrived from France in 1789) and noble women's associations to cover the care of foundling children. The Carlist Wars led to the displacement of rural populations and an interruption of communications, lethal blows for the networks that distributed foundlings from towns to countryside.Footnote 4 It was not until the Law of Benevolence of 1849, which granted power for this branch of charity to provincial boards, and the General Law of Disentailment of 1855, which spelled the end of foundling hospitals' assets, that the Spanish system of benevolence and assistance was completely defined.

The different functions fulfilled by foundling hospitals conditioned the recruitment, work and wages of wet nurses. Illegitimacy and poverty were the two «classic» causes of child abandonment. Recent investigations give more weight to temporary abandonment, which was a consequence of family crises and which increased when it no longer meant the loss of custodial rights.Footnote 5

4. SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY

Our research responds to several related questions. Approximately how many women were involved in this occupation in the 18th and 19th centuries? Where did the workers come from and how did their areas of origin change over the centuries? What was the level—and trend—of their nominal and real wages? What do we know about their family economics, the occupations of their husbands and the weight of wet-nurse wages in family incomes, both rural and urban? To what extent are strong regional differences in wages explained by institutional factors and by the characteristics of regional labour markets?

We have located 160 foundling hospitals in Spain, including the peninsula, the archipelagos and the fortified cities of Orán and Ceuta in northern Africa. These hospitals provided our primary sources: payment and wage books for women, receiving and exit books for foundlings and receipts for the delivery of children. These sources record the following kinds of information, which we have collected in databases.

(1) Circumstances of the child's abandonment—Date and time of entry; whether the child was abandoned anonymously, delivered by someone or found in a public place.

(2) The abandoned child—The information recorded was different for illegitimate and legitimate children. In the first case, sometimes all that would appear was the name the child should be called and some object (a scrap of cloth or ribbon, a small medallion) that would allow it to be identified in case the parents could at some point in the future recover the child (Styles Reference Styles2010). For legitimate foundlings, much more information was recorded: who left it and when, the cause of abandonment (poverty, mother deceased, hospitalised or imprisoned), name and parents' surnames and address. In both cases, hospital officials were primarily worried about whether the child had been baptised.Footnote 6 Since this was normally not known, the child would be immediately baptised and, in the process, given a name, customarily that day's saint. The child's age, an approximate calculation, was also noted.Footnote 7

(3) The wet nurse—As hospitals were legally required to know foundlings' locations, they recorded the wet nurse's name and surnames, place of residence, civil status, husband's name and sometimes his trade (very rarely, the wet nurse's occupation), paid monthly wages and various observations (such as complaints and fines) noted in the margin.Footnote 8

(4) Events of the upbringing—Changes of wet nurses (when and why one wet nurse left the child and with whom it then departed), date when the child moved from nursing to weaning, date when the foundling was returned to the institution and reasons why (illness, disability or death, the latter accompanied, in the 19th century, with a medical certificate indicating the cause of death).

(5) Fate of the child if it survived and «reached the age»—Date of return to the institution, whether the child was taken in or legally adopted by the wet nurse's family or by another family, whether the child was returned to a hospice. Some books include notes about the boy or girl's later life, such as marriage certificates, and statements of becoming a soldier.

We also use other documentation produced by foundling hospitals: accounting ledgers, which recorded the total amount of wages paid to external wet nurses; and minutes and reports of the governing boards, which recorded agreements concerning wage increases and their motivations.

Contemporaries' reports—on an issue that was of «state interest» in the second half of the 18th century—have also been useful. The most important is comprised of bishops' responses to a questionnaire sent out by the Council of Castile in 1790. Earlier that year, an individual, Antonio Bilbao, had directed a presentation to the council denouncing the dramatic situation of foundlings.Footnote 9 The council responded, ordering bishops to

inform on the number of Foundling hospitals that are in your Dioceses, their method of governance, their expenses, rents and distribution; the persons who are in charge; what and how many employees they have; what salaries are assigned to them; the number of Wet Nurses and their wages; to what age breastfeeding is continued; what education is given to the children afterward; how many boys and girls have entered in the last five-year period; how many have died, been adopted, and exist today; from how many and which Towns are foundlings conducted to the referenced hospitals …Footnote 10

The bishops' responses constitute the first systematic source for the number of foundling hospitals, foundlings and wet nurses and their wages in Spain—and were the basis for legislative action taken by the government of Carlos IV. Early 19th-century reports on the medical state of foundling hospitals, collected by Ruiz de Luzuriaga (Reference Ruiz De Luzuriaga1817–1819) and preserved in the Royal Academy of Medicine, include the number of internal and external wet nurses. Madoz's Dictionary (Reference Madoz1844–1849) reports on 128 foundling hospitals in all of Spain; wet-nurse wages are provided for forty of them. We have also utilised official bulletins of the provinces (a territorial organisation established in 1833), statistical yearbooks, medical surveys and contemporary press accounts. Finally, we located 122 ordinances and regulations for foundling hospitals between 1700 and 1900.

With these sources, we have been able to calculate the number of external wet nurses who worked for foundling hospitals for a series of years. Their names allowed us to avoid double-counting women who raised more than one foundling. With information on their places of residence, we were able to calculate the percentage of rural and urban wet nurses, confirming that it was an activity fundamentally performed by peasant women and identifying the specialisation of certain rural districts and urban neighbourhoods in the activity.Footnote 11 Finally, we calculated annual incomes earned from breastfeeding and weaning, as well as the relative weight of these incomes with respect to that of husbands' wage labour in agriculture or construction.

For each foundling hospital, we constructed two series of nominal wages for external wet nurses: one for breastfeeding wages (most commonly until 18 months) and one for weaning wages (in most cases until 7 years). We converted all monetary units into reales de vellón, the most customary unit of currency until the peseta was introduced as the official currency in 1868. Board minutes, ordinances and correspondence have confirmed the dates of wage increases. The wages of foundling-hospital wet nurses make it possible to construct exceptionally long, steady, reliable, and comparable series—in our case, two-century-long series for all Spanish provinces.

The number of wet nurses working for a foundling hospital depended on the number of foundlings, the proffered wage and the likely number of compensated rearing years. Numerous testimonials by hospital leaders attest to what we could call a reserve wage, beneath which workers could not be found to take the position. There is much evidence for this reserve wage—unsatisfied demand for wet nurses and the frequent return of children when breastfeeding wages changed to weaning wages. The reserve wage depended, in turn, on other remunerated work options for these women and their husbands.

At the beginning of the 18th century, about 6,000 wet nurses worked for the foundling hospitals for which we have data, a number that grew to 23,000 in 1850 and approached 14,000 in 1900. (The figure for 1900 is an undercount, since we don't have information for Madrid's hospital, which provided the greatest number of wet nurses, up to 4,000 in different years of the 19th century.) For all of Spain, throughout the 19th century, Pérez Moreda calculates that about 30,000 wet nurses worked for foundling hospitals in any given year (Pérez Moreda Reference Pérez Moreda2005, p. 132).

5. WAGES OF WET NURSES: LEVELS AND TRENDS ACROSS TWO CENTURIES

Recent studies of the evolution of European living standards during the modern and contemporary periods have given a leading role to the wages that women provided to family economies. These studies note the many documentation difficulties in finding reliable, representative, homogenous and sufficiently long wage series for jobs undertaken by women (Humphries Reference Humphries2013). To address these problems, we propose the use of wages earned by external wet nurses of Spanish foundling hospitals during the 18th and 19th centuries. These wages constitute an exceptional case, since they fulfil all of the criteria required for their use (Pérez Romero Reference Pérez Romero2019, pp. 83-84).

One of the problems of working with wages is not knowing whether the given occupation remained the same over time. This problem affects, for example, the wages of construction workers (Allen Reference Allen2001; Ericsson and Mölinder Reference Ericsson and Mölinder2020; García Zúñiga and López Losa Reference García-Zúñiga and López Losa2021). In our case, the job being remunerated was always the same—rearing a child, which included feeding, clothing, cleaning and generally caring for the child.

Our wages also fulfil a premise of constant productivity that in many cases invalidates the wages now being used on a large scale. Wet nurses were workers who did the same job at the same speed and with the same intensity.Footnote 12 So the challenge of assigning value to a worker's productivity—that is, to the intensity, speed and skill with which she did her job—and then figuring out to what extent differences in productivity were reflected in hourly wages, disappears in the case of wet nurses. Quite simply, a wet nurse's wages paid for a month's worth of breastfeeding and childcare.

These were monetary wages, so the problem of attributing a value to payments in kind also disappears. Payments in kind, a common form of remuneration in the modern era, were not possible for staffs as large as those of the foundling hospitals.Footnote 13 Such payments that do show up in the records of some foundling hospitals were limited to clothing given to wet nurses when they took out children and were not part of their wages. Women were required to return the clothing when a child died; otherwise, the clothing would be discounted upon final settlement to prevent its resale.

During inflationary periods, monetary payments implied an advantage for the institutions. Instead of having to buy goods such as wheat and clothing at inflated prices, they could pay wet nurses with devalued currency.Footnote 14 The lack of an in-kind component may lie behind the fall in the supply of wet nurses during times of inflation and, at least in part, help explain hospitals' chronic difficulty in covering demand.Footnote 15

Wet-nurse wages always referred to monthly payments, though they might be collected by the quarter or half-year in order to avoid the costs of travelling to the city. This allows us to calculate daily wages (if a child died on the sixth day of the month, the wet nurse was paid an amount corresponding to those working days) and annual wages and compare them with wages for other jobs (Humphries and Weisdorf Reference Humphries and Weisdorf2019).

These wages have another benefit for historians: because they were paid to workers without formal skills, skill premium is not an issue. Although a woman could take up the profession from the humblest social class (as in the majority of cases) or from a more comfortable social position (in a minority of cases), the work for which a wage was earned was the same: rearing a child for a month. Therefore, the wages are comparable across regions and countries. In contrast to other wages used in historiography, there is no urban premium either. The wage for a city wet nurse is the same as the wage for a rural wet nurse. (Indeed, in the few exceptions for which there is a wage difference, the premium is reversed in order to offset the costs of wet nurses' travel to the city to collect wages; to create incentives for the rearing of children far from cities, where there were more chances for their survival; and to remove children from the poverty of the urban setting, which was frowned upon by the incipient bourgeois society.)

From the wet nurse's perspective, an advantage of receiving monetary wages was the ability it gave her to meet unforeseen expenditures. The baskets of goods we use to make living-standard calculations include basic, daily consumption goods but do not take into account unexpected expenditures. It is possible that covering such expenses was an important incentive for working as a foundling-hospital wet nurse. In an economy of extreme poverty, any unexpected expense could cause a crisis situation, and cash from these wages could provide effective relief.Footnote 16

The work afforded women a number of other advantages. If a woman found herself in a dire economic situation, a foundling hospital might advance her a month's wages. We aren't aware of other occupations that offered unskilled workers immediate, upfront liquidity in the 18th and 19th centuries. Workers decided the number of months they wished to work. If a foundling died, a wet nurse could take out another child immediately, without losing a day of wages (see Table 3). Since the occupation of foundling-hospital wet nurse was year-round, it could compensate for the seasonality of agricultural day wages and thus allow for better planning of family consumption and spending. Finally, a wet nurse who took in a child from a foundling hospital was guaranteed several years of monthly income (weaning wages, although lower, would let her escape the milk restriction). During their early years, foundlings could be used to beg, and when families could no longer garner a wage for their care, some families adopted the children as a source of labour, even putting them out to work in order to collect their wages (Schneider Reference Schneider2013, p. 112; Horrell and Humphries Reference Horrell and Humphries2019). These advantages must have compensated for the low level of wages and help explain why the wages continued to be appealing despite frequent episodes of nonpayment and delay.

Figure 1 shows the evolution of wages received by the women contracted by foundling hospitals over 200 years of the study.

FIGURE 1 NOMINAL MONTHLY WAGES OF EXTERNAL WET NURSES IN SPAIN, 1700-1900 (10-YEAR AVERAGES, IN REALES DE VELLÓN).

Source: Based on Sarasúa (Reference Sarasúa2021a). Data given in Appendix 1.

The figure shows 10-year averages for the foundling hospitals for which we have data in each period. Breastfeeding and weaning wages followed a similar trajectory. A first stage of sluggishness, during which low wages barely changed, would last from 1700 until the 1780s. The testimonies we collected concur that nominal wages in the last decades of the 18th century were too low to attract a sufficient number of wet nurses. In Zaragoza, «For the shortness of the stipend … the same as was given two hundred years ago, there are few women who show up». In Valencia, children accumulate in the hospital, «for a woman cannot be found who would want to take them to her house to nurse and cloth, because of the small stipend of fifteen pesos per year» (cited in Pérez Moreda Reference Pérez Moreda2005, p. 79). Or, in Palencia, where in 1756 and 1758 appeals were made in many of the province's towns, announcing a raise in wet-nurse wages, with the hope that no children would be left in the hospital for upbringing (Marcos Martín Reference Marcos Martín1985, pp. 654-655). This would be a constant refrain: wages determined the supply of wet nurses, which determined children's survival.Footnote 17

From the 1780s to the mid-1820s, wages increased. The change is probably due to the social advances of the enlightenment—an acknowledgement of wet nurses' indispensable social labour. Coinciding with the crises of the old regime (treasury crisis, War of Independence and the beginning of the wars for emancipation in the American territory), this upward trend is a reliable reflection of the high inflation experienced during the final years of Spain's old regime (Reher and Ballesteros Reference Reher and Ballesteros1993, pp. 121-122).

Nominal wages subsequently suffered an important decline, mostly during the First Carlist War and the difficult installation of the new liberal order in 1833. During these years, public institutions—now the sole operators of the foundling hospitals—lacked funds to pay the wages offered in earlier decades, so wage cuts and reductions in breastfeeding months became generalised, while long delays affecting payments were common. Our final period, from the mid-19th century until 1900, shows a clear and constant increase in wages, consistent with the evolution of the Spanish economy, by then immersed in a slow but continual industrialisation process.

The growth of nominal wages between 1700 and 1890 did not imply a process of wage convergence across the national territory. If anything, the opposite occurred, as the data in the Appendix show. Wage differentials produced «interior migrations» within some regions, albeit without physical displacement. Many women appeared as wet nurses on the rolls of foundling hospitals other than those of their provinces, always opting for higher wages. Despite such movement, wage inequality between regions increased strongly. This lack of convergence could reflect several factors: wet-nurse wages did not respond to differences in human capital; opportunity costs were different for women in different regions and cities; in the absence of a well-integrated interior market, price differences for consumption goods persisted; institutions managed the turbulent transition from the benevolence of the old regime to the publicly financed liberal administration with different levels of success.

To better examine the evolution of wet nurses' wages in the context of the national economy, we have converted nominal wages into real wages, deflating with the price series configured by Allen (Reference Allen2001) on the basis of 1800 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 REAL WAGES OF EXTERNAL WET NURSES IN SPAIN, 1700-1900.

Source: Sarasúa (Reference Sarasúa2021a) for wages and Allen (Reference Allen2001) for prices. Wage data given in Appendix 1.

In contrast to nominal wages, real wages show a clear decline throughout the 18th century. It should be noted that nominal wages could not keep with inflation, particularly in the second half of the century.Footnote 18 A significant increase in real wages would not occur until the crisis of 1803; the ensuing increase would last until the end of the 1820s, only interrupted by the turbulent period of the War of Independence. The recuperation of real wages would suffer a reversal (as would nominal wages) in the 1830s, when the charitable system of the old regime was breaking down and the institutions created by the liberal bourgeois state were assuming their duties—and when foundling hospitals were restructuring their battered economies. Finally, real wages began a clear ascent at the end of the 1840s, a rise similar to that of nominal wages, confirming the improvement of wet-nurse remuneration.Footnote 19

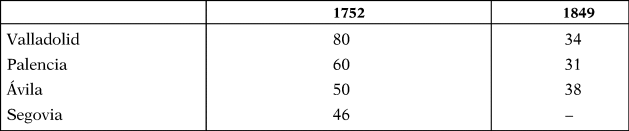

To examine the importance of these wages for family budgets, we selected several interior provinces for which we have accurate data and compared their wet-nurse wages with the annual income earned by day labourers in two years: 1752 (from the Cadaster of Ensenada) and 1849 (from the Survey of Agriculture Day Wages).

Table 1 shows that the contribution of these women became less important to family incomes, which depended mainly on wages earned by day labourers. From an average of 59 per cent of the day labourer's annual income at the mid-18th century, women's contribution dropped to about 30 per cent by the mid-19th century.Footnote 20 The crisis of the benevolent institutions, aggravated by processes of disentailment that occurred during the period, had begun to take its toll. Nonetheless, thousands of impoverished families continued taking in foundling children as a basic element in their strategy for achieving the minimal goal of subsistence.Footnote 21

TABLE 1 PERCENTAGE OF DAY LABOURER'S ANNUAL INCOME THAT A WET NURSE EARNED FROM A BREASTFEEDING WAGE

Source: Hernández (Reference Hernández García and Sarasúa2021).

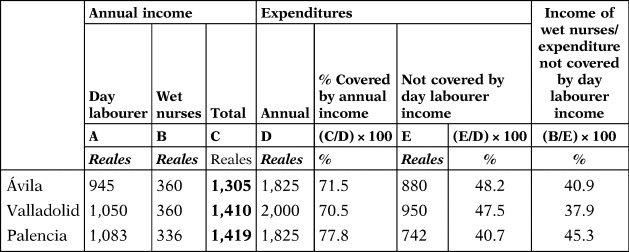

Table 2 shows that a day labourer's wage covered only about half what was needed for family subsistence. The other half would have to come from the day labourer's work in other occupations, from paid work done by woman and children, or, most frequently, from a combination of both. The work of wet nurses was one of the strategies designed by these pluriactive families, as was spinning wool, cleaning bundles of clothes, and having young members of the household help out with grazing labours. For a woman who could nurse a child because her own child had died or reached weaning age, wet-nursing was an opportunity she could not afford to pass up. The wage she could provide would reduce by approximately 40 per cent the annual gap between income and expenses. It was not a complete solution, but it was a complementary and attainable part of the solution.Footnote 22

TABLE 2 IMPACT OF WET-NURSE WAGE ON THE FAMILY ECONOMY, 1849 (REALES)

Source: Hernández (Reference Hernández García and Sarasúa2021).

Just as important as knowing the monthly wage is knowing how long the wages were collected. Since wet nurses could, if they wished, work 365 days per year, the question concerns the biological limits of nursing capacity. We were able to reconstruct several wet-nurse «work histories», which show how women structured the occupation. María Gil, of Alcalá de Henares, married to Juan García Moreno—who declared his occupation, successively, as bricklayer, rental mule purveyor and lime worker—took out a girl to nurse from the foundling hospital of Madrid (30 kilometres away) in June 1702. When the girl's breastfeeding ended in December 1703, Gil combined her weaning with another girl's breastfeeding. In October 1709, she took out a third child for weaning and asked for an advance «because she finds herself in great need, according to the priest of that parish». This boy reached the age of return in June 1713 but was left in Gil's care until Christmas «because he was dropsical and very small» (Table 3).

TABLE 3 WORK TRAJECTORY OF MARÍA GIL (1702-1716)

For 3 years, Gil received two weaning wages (20 reales per month), until in May 1711 she took out a third child for weaning. In the thirteen and a half years that she worked continuously for Madrid's foundling hospital, Gil nursed two girls for 53 months, and cared for three boys for a total of 238 weaning months. She earned a total of 3,334 reales, an average wage of 20.5 reales per month. Despite her poverty, she successfully raised two girls and three boys, who reached the «age of return» and were sent back to Madrid, to respective hospices.

6. «SPILLED ACROSS MANY TOWNS»Footnote 23: THE MAINLY RURAL PROVENANCE OF WET NURSES

XV. All diligence should be expended so that in the general Foundling Houses a large number of them do not reside, which is very opposed to health, and consequently neither should the House have many wet nurses; for although one or a few may be maintained preventatively to nurse the Foundlings that arrive, the Administrator should seek to know the town, where some wet nurse exists in order to send it without delay.

Decree of His Majesty on December 11 of 1796, which contains Regulation for the Policing of Foundlings, which His Majesty orders to be observed in all of his Dominions.

The majority of wet nurses contracted by foundling hospitals were sought outside cities. One reason was economic—as the wages offered were very low, it was easier to recruit wet nurses in rural localities, where the cost of living was lower. A second reason was related to children's health. Experience with contagious diseases and epidemics had convinced doctors and governors that cities worsened mortality. A third reason was given by the royal decree of 11 December 1796, «Regulation for the establishment of foundling hospitals», which included deliberate policy to provide economic relief to «small towns». Article 9 orders the following.

It should be endeavored that each foundling be nursed and raised in the town where it was [abandoned], unless this was in a populous neighborhood, because if it was, it would be advantageous that the foundlings be given out to be nursed and raised by women residing in small towns; and among them to be spread more widely the relief of the wet nurses' stipend.

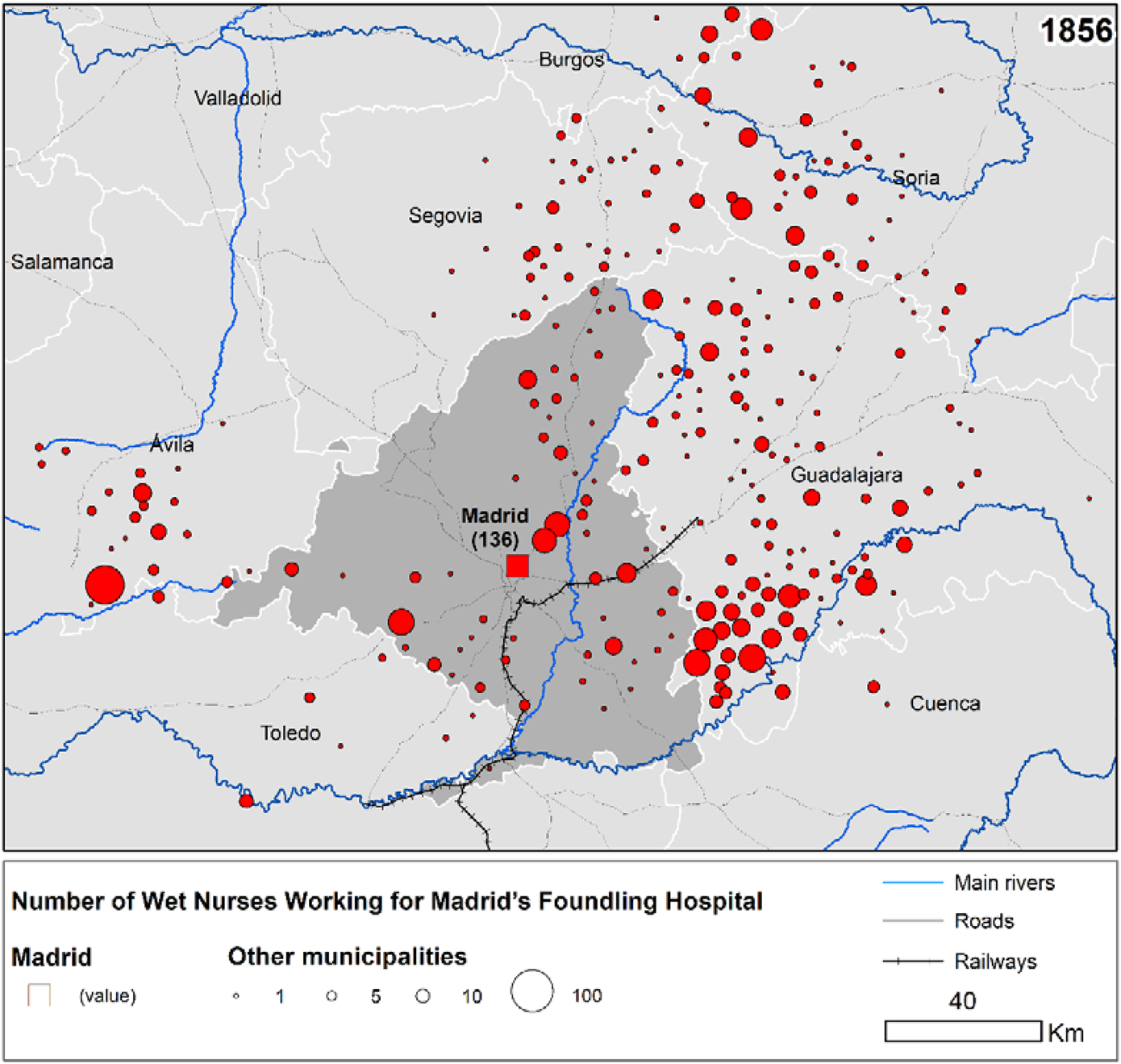

This idea became a mandate that many ordinances would pick up. Foundling hospitals were thus set up in rural regions, a situation vital to an understanding of their operation and their economic impact. As Figure 3 illustrates, in the mid-19th century, the foundling hospital of Madrid (the largest in Spain) recruited wet nurses from towns in eight provinces. Of the 1,799 wet nurses working for Madrid's foundling hospital in 1856 (only considering those who raised foundlings that entered the system that year), just 122 were from the city proper, with another fourteen from rural localities in its outskirts.

FIGURE 3 NUMBER OF WET NURSES WORKING FOR MADRID'S FOUNDLING HOSPITAL.

Source: Sarasúa (Reference Sarasúa and Sarasúa2021b).

All of the big foundling hospitals recruited wet nurses (and took in foundlings) from areas that extended beyond provincial borders. The foundling hospital of Barcelona captured wet nurses from Tarragona, Lérida, Gerona, Castellón and Teruel (López and Mutos Reference López Antón, Mutos and Sarasúa2021); the hospital in Valencia paid wet nurses in the provinces of Castellón, Alicante, Cuenca, Teruel and Valencia (Medina Reference Medina and Sarasúa2021); the hospital in Zaragoza took in Basque, Riojano, Navarrese and Aragonese children and raised them in rural zones of the provinces of Zaragoza, Huesca and Teruel (Erdozáin and Sancho Reference Erdozáin, Sancho and Sarasúa2021) and the hospital of Valladolid contracted wet nurses in León, Zamora, Palencia, Burgos and Segovia (Hernández Reference Hernández García and Sarasúa2021; Hernández and Amigo Reference Hernández García, Amigo and Sarasúa2021).

Rural women had not always been preferred. In the first years of the 18th century, there was a high incidence of urban wet nurses: 39.2 per cent in Madrid (although many lived in neighbourhoods and localities in the city's outskirts), 51 per cent in Barcelona, 51 per cent in Valladolid, 60 per cent in Ávila, 83 per cent in Granada and 39 per cent in Seville (Pérez-Artés and Cabanillas Reference Pérez-Artés, Cabanillas and Sarasúa2021). Rural wet nurses became predominant at the end of the 18th century, which coincided with the first great increase in foundling arrivals at hospitals. By the first decades of the 19th century, only three hospitals had rolls with more than 25 per cent of urban wet nurses (Valladolid, Palencia, Zaragoza) and just two had rolls with more than 50 per cent of urban wet nurses (Granada and Almería). Except for periods of war, which interrupted communications, the tendency for recruitment in rural zones was sustained for the rest of the 19th century.Footnote 24

Thus, a framework of relations was established between the countryside and the city, in part because a portion of abandoned children came from towns. The transfer of foundlings to urban centres generated a network of secondary institutions called cunas (cradles) or hijuelas, generally located in the district capitals, where councils received children in order to send them on to the main institution. Their transport—about which dramatic descriptions exist and which few children survived—created another occupation for women in some regions (such as the Canary Islands), that of the «conductor», who fed foundlings until they arrived in the city (Barrios Reference Barrios and Sarasúa2021). Elsewhere, wet nurses turned to intermediaries (women and men), who took charge of transferring foundlings to and from distant rural zones and collected wet nurses' wages in cities.

One of the key agents in the operation of this labour market was the rural parish priest, who could resolve problems of information and supervision. The contracting institutions could not supervise the work or performance of their workers, who lived far away. Foundling hospitals had regular evidence of fraud: wet nurses who, in order to continue charging, presented different children in place of ones who had died on them; wet nurses who didn't have milk; wet nurses who mistreated children, raised two children at the same time, passed children on to other women, departed with no explanation, or used children to beg. The parish priest, who lived in the same locality as the wet nurse, would be the person who fulfilled a supervisory function.

As «terminals» for the bishoprics, parish priests also played an important role in the diffusion of information about the job. Neighbourhood and family networks were clearly important, but the key source of information was priests, who frequently appeared as recruitment agents, which explains some towns' specialisation in the activity. Finally, the priest was the person in charge of baptising the foundling and certifying its death, registering it in the parochial books that we use today.Footnote 25

An important consequence of these institutions' reliance on surrounding rural territories was the seasonality of wet-nurse supply. During the months for which the opportunity cost for these workers was high because they were employed in mowing or harvesting local crops (grapes, olives), they did not show up to take in children.

When reconstructing the family economies of wet nurses, it is important to take into account that although most were married, a small percentage were single women or widows. For Galician foundling hospitals, the number of single women was significant—24 per cent of those employed in El Ferrol during the 1850s and 1860s, and 42 per cent in Pontevedra from 1875 to 1879 (Dubert and Muñoz Reference Dubert, Muñoz and Sarasúa2021). For Andalusian hospitals, single women were also important—11.2 per cent in Almería in 1860, and 21.5 per cent in Jerez de la Frontera in 1879 (Pérez-Artés and Cabanillas Reference Pérez-Artés, Cabanillas and Sarasúa2021). Widowed wet nurses specialised in raising already weaned children, that is, those between the ages of 18 months and 7 years.Footnote 26 The presence of widows among the ranks of wet nurses confirms that the wages were an important opportunity for the poorest women. The figures for widowed wet nurses in the foundling hospitals of Málaga and Jerez de la Frontera are significant, representing 12.4 and 13.4 per cent, respectively, of those wet-nurse populations between 1860 and 1879. Wet-nursing would be one of the strategies developed by households headed by widows across rural and urban Europe and would vary according to stages in their life and family cycles (Moring and Wall Reference Moring and Wall2017, pp. 147-181).

7. CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests the need to revise some established ideas about the preindustrial economy. By reconstructing the staffs of the country's main foundling hospitals, we have been able to show the enormous number of women who worked for these institutions in the 18th and 19th centuries. This service-sector activity, whose spread signalled the weight of non-agrarian activities in the rural world, indicates that the modernisation of the occupational structure occurred earlier than is commonly affirmed. It also makes clear the importance of taking into account the economic value of these services, which until now have been excluded from calculations of gross domestic product.

The nursing and raising of foundlings were not recognised in municipal enumerator books. Husbands never declared their wives as wet nurses; widows did not declare themselves as wet nurses. The occupation can only be detected in certain cases by the term used to identify a foundling—a child who is living with the family but is not a son or daughter. This was true even though the occupation was created by large public-service businesses, with staffs ranging from dozens to thousands of workers. These businesses only employed women, and mostly married women, the precise section of the population that supposedly had no remunerated occupation. Their work was not limited to the period of breastfeeding. Because it was possible to link consecutive periods of nursing and weaning, the job allowed for stable work, capitalising on pregnancies and births. It was an occupation that stimulated the internal mobility of workers, creating regional labour markets that supported dense networks of information, transport and credit.

Our research also demonstrates the spread of wage work in the 18th century, both in cities and rural zones. The labour of wet nurses transferred considerable monetary resources to the rural economy, particularly to the poorest strata, which helped to reduce indebtedness and to compensate for low agricultural day wages, subemployment and unemployment among men. The wages of rural wet nurses stimulated the circulation of cash (and recourse to credit and pawning), facilitated the payment of taxes and rents and contributed to the diversification of economic activity and the reduction of poverty. These wages were an important source of income for rural households, even for those that possessed or rented land. They represented an income that was neither ancillary nor seasonal and could frequently sustain a family, as demonstrated by the complaints of wet nurses and their husbands when payments were delayed.

Foundling hospitals were more than a source of employment for women and monetary income for their families. Although they could not be too demanding, hospital officials, women's boards, doctors and priests established norms for the hygiene, dress and feeding of children and wet nurses had to conform in order to maintain their wages. Monitored by doctors, priests and neighbours, these women had to strive to improve household conditions as much as possible if they wanted to maintain their wages or take in other children.

The raising of hundreds of thousands of abandoned children (and the education and medical care of those that survived) was a pillar of social care, a precursor to what we know as the welfare state. The wages and employment they offered to women in cities and in the countryside are an extraordinary means of understanding the economy of the poorest sector of the population—which is to say, the majority of the population—in the 18th and 19th centuries. We hope our research will begin a discussion of the extent to which these wages constituted a key contribution to working-class households. Further research is called for.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0212610922000167.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article presents the main results of a research project (HAR2017-85601-C2-1-P) financed by Spain's Agencia Estatal de Investigación. Preliminary results were presented at the Encontro da Associação Portuguesa de História Económica e Social (APHES) (Lisboa, 2018) and at the Jornadas de la Red Española de Historia del Trabajo (Murcia, 2019). We thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful suggestions, and E. Álvarez-Palau for helping with cartography.