Introduction

In the nineteenth century, many newly-described exotic pheasant species, with striking plumage, were introduced into Britain from the Indian subcontinent and the Far East to supplement populations of the common pheasant, which had been resident in Britain since the Roman period, and the golden and silver pheasants, which had been widely kept in aviaries and menageries since the early eighteenth century.Footnote 1 At this time, with the growing interest in acclimatisation, which the historian of science, Michael Osborne, defines as ‘the intended and “scientifically” mediated transplantation of organisms’, attempts were made to naturalise these exotic pheasants on British country estates.Footnote 2 However, with acclimatisation experiments generally failing to meet expectations, naturalisation aspirations for these species were largely abandoned, with even relatively established populations collapsing by the mid-twentieth century, leaving only a few specimens to roam the British countryside, their descendants continuing to attract attention from those in pursuit of a rare but memorable encounter with these beautiful birds.Footnote 3

Scholarly discussions on introduced exotic species in Britain have so far tended to focus on the fauna and flora that have profoundly affected local ecologies, such as the grey squirrel, the American mink, and hybridised rhododendrons.Footnote 4 However, historians are increasingly recognising that research into those introduced species, whose presence in Britain was perhaps short-lived or too limited to a specific, geographical area to have a significant or long-term impact, can provide new insights into broader themes within Environmental and Animal History, as demonstrated by Peter Coates’ recent study on the muskrat in Britain.Footnote 5 Whilst the common pheasant has received some attention from researchers within the field of rural history, through studies on the large-scale effects of pheasant shooting on the British landscape from the mid-eighteenth century onwards and on popular opposition to the Game Laws in the nineteenth century, introduced, exotic pheasants in nineteenth-century Britain have received little attention, other than in broader works on acclimatisation and introduced species, such as those by Christopher Lever.Footnote 6

This study examines the presence of Reeves’ pheasant (Syrmaticus reevesii) in Britain, which, compared to the golden pheasant and Lady Amherst’s pheasant, remains relatively unexplored within recent, popular literature on British birds.Footnote 7 It particularly investigates how encounters between the British and Reeves’ pheasant informed their imaginings of the species, from its first introduction into Britain from China in 1831, when a single, live, male specimen was presented to the Zoological Society of London (the ZSL), to 1913, when a serious decline in its numbers was starting to be recognised. Drawing on natural history texts, records from the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, technical literature on pheasant rearing, and extracts from periodicals, magazines, and generalist encyclopaedias, this study demonstrates how imagined and physical encounters with Reeves’ pheasant, by naturalists, acclimatisers, pheasant enthusiasts, and sportsmen, informed shifting constructions of the species, which ultimately impacted its presence in Britain.

This article contributes to the growing body of research on introduced species in Britain by demonstrating how British imaginings of Reeves’ pheasant evolved as sites of encounter between the British and this species changed in the nineteenth century due to Britain’s developing, informal empire in China, which facilitated the proliferation of Reeves’ pheasant in Britain. Within this context, understandings of Reeves’ pheasant evolved, from initial imaginings of it as a beautiful, mysterious but theoretical species, to new understandings of it as a rare and valuable, exotic aviary bird and then an ideal gamebird, the ‘king of pheasants’ and the ‘pheasant of the future’. However, by the early twentieth century, owing to new observations of the species’ aggressive behaviour towards other pheasants and its broad dispersal range, the species increasingly failed to meet these high expectations.

From Phasianus superbus to Reeves’ pheasant: early encounters and initial constructions

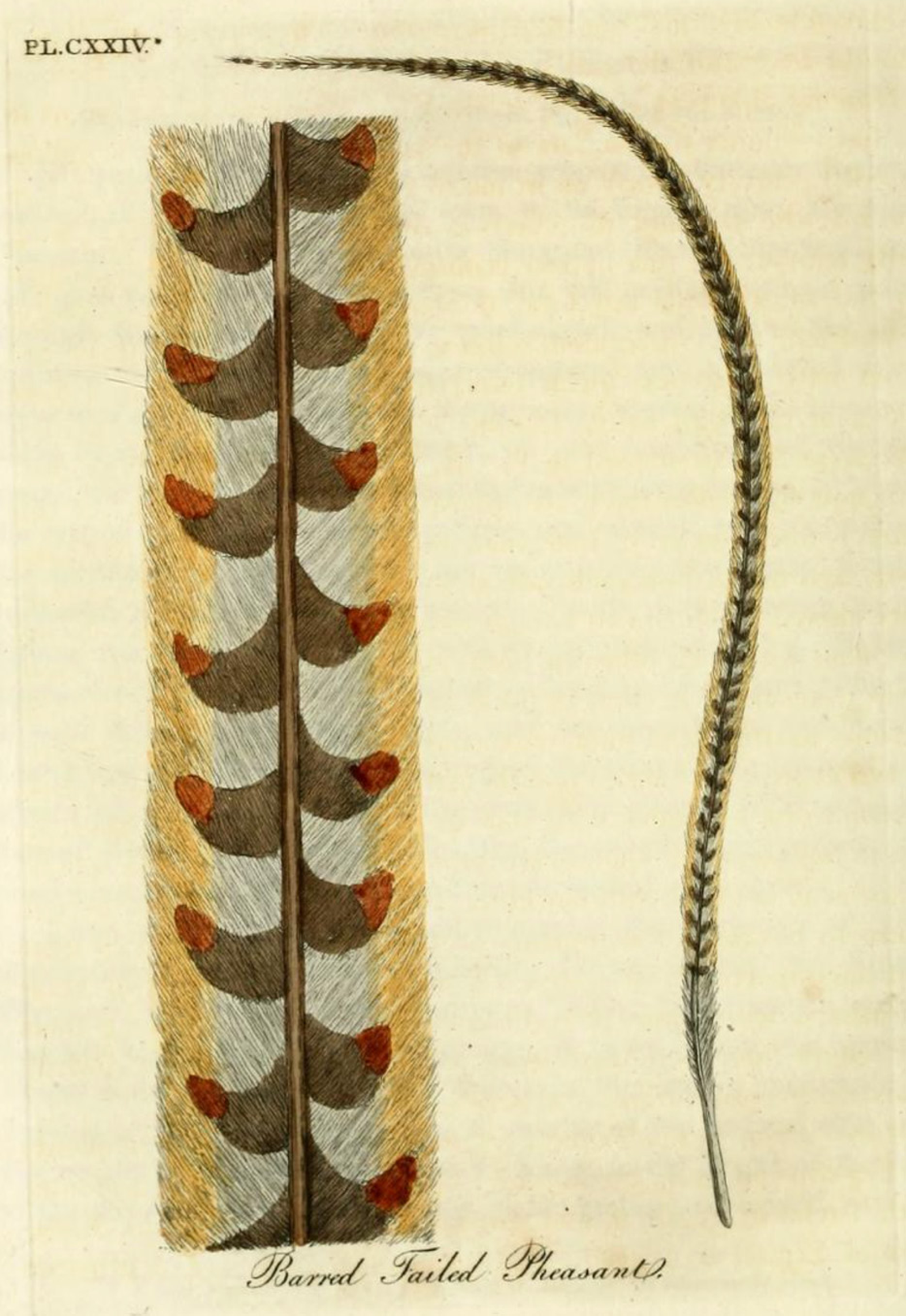

Long before the arrival of the first live specimen in 1831, Reeves’ pheasant had been imaginatively encountered in Britain through descriptions, by European naturalists, of a mysterious, beautiful bird with an extremely long tail, which frequently appeared on high-status Chinese commodities, such as porcelain, silk robes, brocade-work, wall hangings, and in Chinese books. In response to these images, Carl Linnaeus described and named a theoretical species, Phasianus superbus, in 1771, which provided the initial conceptualisation of what was later to become Reeves’ pheasant, his description being repeated by other eighteenth-century naturalists, such as John Latham and Charles-Nicolas-Sigisbert Sonnini de Manoncourt.Footnote 8 Whilst Sonnini expressed doubts regarding the existence of P. superbus, speculating that it might only exist ‘in the imagination of Chinese painters’, Latham, in his 1783 A General Synopsis of Birds, argued in favour of its existence, linking it directly to a drawing ‘of the tail feather of a bird of the Pheasant kind, which measured above six feet in length’, based on an original sample from China.Footnote 9 In doing so, Latham forged a connection between P. superbus and Reeves’ pheasant that would strengthen as more specimens of the latter reached Europe in the early nineteenth century.Footnote 10

As sites of encounter with P. superbus were solely limited to high-status Chinese goods, and even the first Reeves’ pheasant tailfeathers entered Europe as rare and valuable commodities, the sentiments already invested in these high-status objects were instantly and directly transferred into early British constructions of Reeves’ pheasant as a beautiful, mysterious, rare, and valuable exotic bird. These early interactions with Reeves’ pheasant through depictions on Chinese goods and commodities, sourced largely from the port of Canton, were a product of Chinese restrictions on European access to China in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, which limited the ways in which naturalists could encounter Chinese flora and fauna. As the historian of science, Fa-ti Fan, explains, ‘with only minimal freedom of movement’, European naturalists in Canton ‘rarely went farther on their “expeditions” than the gardens, nurseries, fish markets, drugstores, and curio shops’.Footnote 11

In 1813, the Dutch ornithologist, Coenraad Temminck, published a description of P. superbus that centred around his analysis of two Reeves’ pheasant tailfeathers, which had probably been purchased at the Canton markets and had reached him through his father’s connections as treasurer of the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC).Footnote 12 As Temminck’s physical encounter with this species was limited to its tailfeathers, his description invariably focussed on this impressive element of the bird’s physiology as the species’ defining feature.Footnote 13 Like Linnaeus and Sonnini, Temminck reinforced the bird’s high status by linking it to the highly-regarded commodities on which it was frequently depicted, such as Chinese paper ‘of the best quality’ and ‘expensive Chinese robes’. He further configured the species’ economic value by claiming that its tailfeathers were sold for large sums of money in China.Footnote 14 Latham similarly encountered Reeves’ pheasant tailfeathers in the form of commodities, recounting, in his 1823 A General History of Birds, how the drawings of tailfeathers that he had previously described (see Fig. 1) matched ‘a bundle of thirty or forty of these tail feathers, which were brought from China’.Footnote 15

Figure 1. The illustration of a Reeves’ pheasant tailfeather from John Latham’s A General History of Birds (London, 1823).

Source: Google Books.

Noting that a complete specimen of P. superbus could not ‘be found in any study of Europe’, Temminck concluded that ‘the laws and the strict prohibitions which exist in China on the exportation of this pheasant, will render it always rare’, a claim that contextualised the failure of European naturalists to acquire physical specimens within a broader discourse of oppressive Chinese isolation and seclusion.Footnote 16 As the scholar, David Porter, observes, it was not uncommon for eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century English writers to utilise metaphors of ‘circulation’ and ‘blockage’ in their criticisms of Chinese trade and travel restrictions, which were often presented as constraints on the natural flow of commerce and information.Footnote 17 In issue 82 of his Nouveau Recueil de Planches Coloriées D’Oiseaux, published in 1830, Temminck, believing that his tailfeathers did not belong to P. superbus, provided a detailed description of his new pheasant species, which he named the ‘Faisan Vénéré’ (Phasianus veneratus), reiterating his Chinese restriction claims by explaining that this very rare bird, ‘from the outermost reaches of the Empire’, was kept in the aviaries of wealthy Chinese and was very valuable, its exportation prohibited under severe punishment.Footnote 18

Temminck’s new description followed his acquisition of two complete male Reeves’ pheasant skins, which were also used to create the accompanying, detailed colour plate of the species (see Fig. 2). According to the Australian naturalist, George Bennett, writing in 1834, Temminck’s specimens were ‘very probably’ sourced from the Macao aviary of the prominent British opium dealer and amateur naturalist, Thomas Beale.Footnote 19 This evidence suggests that, at this time, the aviaries of British merchants in China were acting as sites where the British could encounter live specimens of Reeves’ pheasant and were, therefore, instrumental in shaping early British conceptions of the species as a high-status aviary bird. In this respect, British understandings of this pheasant were clearly shaped by their observations of Chinese relationships with the species, the keeping of Reeves’ pheasant in British aviaries in China clearly mirroring the established practices of the wealthy Chinese.

Figure 2. The ‘Faisan Vénéré’, from Temminck’s Nouveau Recueil de Planches Coloriées D’Oiseaux (Paris, 1838).

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Temminck was, however, unaware that his faisan vénéré had already been officially described and named ‘Reeves’ pheasant’ in 1829 by the British naturalist, John Edward Gray, following his examination of a live specimen supplied to him by John Reeves (1774–1865), an amateur naturalist working as a tea inspector at the Canton factory of the British East India Company (BEIC).Footnote 20 It is likely that Gray carried out his examination of the bird in India, during Reeves’ return to Britain from China, as Gray’s 1832 work, Illustrations of Indian Zoology, included a picture of Reeves’ pheasant, based on ‘a Chinese drawing made under the inspection of Mr Reeves from a living bird’, that was first published on 1st June 1829 (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The image of Reeves’ pheasant in Gray’s Illustrations of Indian Zoology (London, 1832), based on an image supplied by John Reeves.

Source: The Internet Archive.

Reeves’ presentation of his live specimen to the ZSL on 31st May 1831 was not a unique or isolated event, as he had repeatedly sent live and preserved specimens of Chinese fauna and flora, as well as watercolour illustrations by Chinese artists, to experts in Britain during his time in China.Footnote 21 Indeed, as a member of the ZSL, the Horticultural Society, the Royal Society, and the Linnean Society, Reeves had already gained quite a reputation as an expert on Chinese natural history long before his retirement from the BEIC in 1831.Footnote 22 Fan claims that, as Reeves possessed ‘little scientific training’, his status ‘derived less from his learning than from his zeal, social connections, and economic resources’, arguing that ‘so little was known about China that the scientific community in Britain welcomed almost anything’.Footnote 23 Nevertheless, entries on Reeves’ pheasant in British works of natural history frequently praised John Reeves for supplying ‘the first individual of this rare and magnificent species ever brought alive to Europe’.Footnote 24

British merchants based in China were ideally placed to secure natural history specimens because they could take advantage of the growing networks of imperial trade to transport specimens to Britain, a practice actively encouraged by many major British trading companies, such as the BEIC, which openly fostered a collecting ethos amongst its employees.Footnote 25 This resonated with the growing enthusiasm for the study of natural history in nineteenth-century Britain, which was largely expressed through the collecting and classifying of samples, fuelled by a contemporary, imperial drive to expand into and order the natural world.Footnote 26 Indeed, Reeves’ successful transportation of his pheasant specimen to the ZSL using the BEIC trade network corresponded with the broader movement of natural history specimens across the world through British, imperial, and colonial transportation systems that enabled British trading companies to supply national natural history institutions, such as the ZSL.Footnote 27 As Fan points out, the growing imperial networks of trade with China meant that ‘dozens of living Chinese animals donated to the Zoological Society of London in the 1830s must have been picked up in the markets of Canton’.Footnote 28

According to Bennett, Reeves’ live specimen was also supplied by Beale, who, after ten years of searching, had managed to acquire four males ‘from the interior of China… purchased for one hundred and thirty dollars’.Footnote 29 Fan points out that Beale’s investment of time and resources was typical of naturalists who wanted to procure special birds from more remote parts of China ‘through the networks of inland trade’, with his aviary being particularly famed for its extensive collection of rare and unusual birds.Footnote 30 These early British encounters with Reeves’ pheasant in aviaries in China clearly helped to shape early constructions of the species as a beautiful, rare, and valuable aviary bird. Commenting on a Reeves’ pheasant in Beale’s aviary, Bennett presented the species as a valuable addition to any aviary, emphasising its ‘beautiful tail feathers’ and noting how it ‘strutted about proudly, arrayed in its elegant plumage; occasionally approaching near the wires of its habitation, to let the visitors notice and admire him’.Footnote 31 Bennett also observed that female specimens were particularly difficult to procure due to the lack of value that the Chinese attached to them compared to the male specimens, with their far more striking plumage, revealing how Chinese conceptions of the species as an aviary bird directly hindered the availability of some specimens to British merchant-naturalists.Footnote 32

Reeves’ pheasant in Britain: a rare, magnificent aviary bird

The ZSL acted as the initial site of encounter for many introduced, exotic pheasants in nineteenth-century Britain, with the first, live specimens of both Lady Amherst’s pheasant and the Himalayan monal being presented in 1831, the green or Japanese pheasant in 1840, and the copper pheasant in 1866.Footnote 33 As acclimatisation was one of the principal concerns of the early ZSL, these newly acquired specimens were immediately assessed for their domestication potential, a process that resonated with the interests of many of the society’s gentlemen members, who were keen to stock their parks and farms with a wide array of ‘useful’ exotic fauna.Footnote 34 These preoccupations and assessments not only informed how exotic pheasants were depicted in ZSL publications but also frequently drove society’s efforts to propagate these species in Britain. In Edward Turner Bennett’s 1835 guide to the Zoological Gardens at Regent’s Park, for instance, golden and silver pheasants were both presented as easily domesticable, with the ultimate goal being the complete naturalisation of these species in the coverts of British estates.Footnote 35 London Zoo also devoted much of its attention to the propagation of exotic pheasants, with the attempts to breed several Indian species between 1858 and 1860 proving to be particularly successful.Footnote 36 The Acclimatisation Society of Great Britain (ASGB), founded in 1860, also became solely concerned with the breeding of exotic game birds from 1865 to 1867, importing a large number of exotic pheasants from India in 1866.Footnote 37

Within this context of species characterisation and evaluation, Reeves’ pheasant was favourably compared to other exotic pheasants already being kept in British aviaries, which reinforced its status as an impressive, beautiful, and ornamental aviary bird. The Penny Cyclopædia, for instance, described the ‘noble Reeves’ Pheasant’ alongside the ‘gorgeous Gold Pheasant’ and the ‘delicately pencilled Silver Pheasant’ as ‘magnificent… species, which exhibit such a prodigality of splendour and beauty in their plumage as almost realises the birds which we read of in fairy tales’.Footnote 38 It further stated that golden and silver pheasants were ‘common in almost every aviary, and there is no reason why they should not thrive well if turned out in our preserves’, implying that Reeves’ pheasant would equally thrive in these conditions.Footnote 39

Although this rather informal assessment of Reeves’ pheasant imagined it thriving in British coverts, most constructions of the species in Britain during this period continued to present it as an aviary bird, a characterisation that was reiterated across many early-nineteenth-century British publications, such as works of popular natural history, geographical accounts of China, and popular encyclopaedias. Owing to the brevity of Gray’s 1829 description, authors of these works tended to draw on Latham and Temminck’s more detailed descriptions of the species, transferring the same emphasis that they had placed on the bird’s spectacular plumage and its long, beautiful tailfeathers, as its defining features, and making the same references to the keeping of it in Chinese aviaries and the prohibitions placed by the Chinese on its exportation, even though the latter had already been thoroughly rejected by Bennett.Footnote 40 The colour plate in Temminck’s 1830 work similarly served as a template for later illustrations of the species in British publications, such as Sir William Jardine’s The Naturalist’s Library (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4. The illustration of Reeves’ Pheasant in Jardine’s The Naturalist’s Library (Edinburgh, 1834).

Source: The Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Live specimens of Reeves’ pheasant entered Britain sporadically following its presentation to the ZSL in 1831, with another male Reeves’ pheasant being given to the ZSL by John Reeves in 1834 and a female being supplied by Reeves’ son, John R. Reeves, in 1838.Footnote 41 The first specimen to be held privately in Britain was acquired in 1862 by John Kelk, a Fellow of the Zoological Society, his bird roaming ‘in perfect liberty and in excellent health for two successive years among other pheasants at his seat, Stanmore Priory, near Edgware’ before being donated to the ZSL in 1864.Footnote 42 The ASGB similarly boasted a single, ‘nearly pure-bred cock Reeves’ pheasant’ in 1864.Footnote 43 Indeed, Reeves’ pheasant continued to be regarded as very rare in Britain well into the 1860s, with one popular work of ornithology, published in 1863, stating that although the species was present in Britain, it did not exist in sufficient quantities to warrant the status of a ‘British’ bird.Footnote 44 Owing to their very small numbers and high-value status, specimens were mostly confined to aviary and domestic environments in Britain, which ensured that contemporary encounters with the species continued to occur in similar spaces to those previously observed in China. Consequently, new encounters with Reeves’ pheasant in Britain tended to reinforce earlier imaginings of the species as a beautiful, rare, and valuable aviary bird.

However, by the late 1860s, following the opening of new treaty ports on the Yangtze River at the end of the Second Opium War (1856–1860), the number of Reeves’ pheasant specimens being imported into Britain from China had grown.Footnote 45 As Britain’s informal empire in China had developed, through acts of gunboat diplomacy, access to specimens had improved and British constructions of Reeves’ pheasant were now increasingly viewed through a broader, imperial lens. In his 1869 description of Reeves’ pheasant, for instance, the famed ornithologist, John Gould, stated that, prior to the Second Opium War, this species was ‘so little known to the man of science that it was only by surmise, by grotesque drawings, and the receipt of remarkable feathers of birds that he formed any idea of its ornithology’.Footnote 46 He further elaborated that British naturalists could now ‘not only get skins from this fine pheasant but living examples in considerable numbers’, declaring that, therefore, ‘out of evil comes good; and thus war, with all its horrors, is the precursor of extended knowledge’.Footnote 47 Gould’s judgement largely reflected the general attitude of contemporary British naturalists, who championed the ‘cognitive superiority of the modern Western tradition of factual knowledge’ over non-Western systems.Footnote 48

During this period, the ZSL particularly benefitted from reports by amateur naturalists stationed in China, who were eager to contribute to the gathering of new scientific data on the country’s flora and fauna whilst working for organisations such as the British Army, the Consular Service, and the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service.Footnote 49 Within this context of scientific investigation and assessment, Reeves’ pheasant was newly encountered in spaces, such as the Pekin markets. In 1862, a physician attached to the British Army in China reported to the ZSL that he had sent six male specimens, purchased from local markets, and five female specimens, procured from local trappers operating deeper within the country, to Britain from Shanghai.Footnote 50 British diplomats, who were also deeply involved in the collecting and forwarding of scientific information to Britain, also contributed to the ZSL’s knowledge of this species.Footnote 51 In a letter read to the ZSL in 1866, the British diplomat, Dudley E. Saurin, reported on his encounters with Reeves’ pheasant as a rare commodity in the Pekin market.Footnote 52 Similarly, Sir Rutherford Alcock, who had previously attempted to deliver specimens of the copper pheasant to the ZSL during his term as envoy to Japan from 1858 to 1864, forwarded a letter to the ZSL in 1868 from the well-known French missionary and naturalist, Père David, which contained useful information about the native range of Reeves’ pheasant in China.Footnote 53

The proliferation of Reeves’ pheasant in British aviaries is mostly attributed to the efforts of John J. Stone, an agriculturalist who made numerous attempts to acclimatise exotic pheasants in Britain, including the first successful breeding of Lady Amherst’s pheasant in 1871, and Walter Henry Medhurst, the British Consul to China and a member of the ASGB.Footnote 54 In spite of early failures, Stone and Medhurst successfully transported three male and four female Reeves’ pheasant specimens from the treaty port of Hankou to London in 1866, donating them all to the ZSL, much to the chagrin of the ASGB, to whom they had been originally promised.Footnote 55 Like many other amateur naturalists in China, Medhurst had to rely on the skill and knowledge of Chinese trappers in order to secure his Reeves’ pheasant specimens from deep within the Chinese interior, his contacts and ability to speak local languages aiding the success of his project.Footnote 56 According to Gould, Medhurst was also ‘anxious that the Queen should have early possession of [Reeves’ pheasant] specimens’ and so, ‘one male and two females were offered to and graciously accepted by Her Majesty… [for her] aviaries at Windsor Castle’.Footnote 57 Medhurst’s gift of Reeves’ pheasant specimens to Queen Victoria reflects the broader, royal interest in the breeding of exotic pheasants, with Prince Albert, in his capacity as the President of the ZSL, overseeing the breeding of the Himalayan monal at the ZSL during the 1850s and 1860s to specifically supply birds for the royal aviaries.

Takashi Ito reflects that royal interest in the Himalayan monal stemmed from its status not only as a beautiful aviary bird but also as a product of the furthest reaches of Britain’s Indian Empire, an observation that suggests that the high esteem and interest placed on Reeves’ pheasant similarly presented it as a potent metonym for Britain’s informal empire in China.Footnote 58 The introduction and early proliferation of Reeves’ pheasant in Britain were, therefore, deeply intertwined with narratives of national and imperial prestige, a notion that corresponds with Janet Browne’s observation that acclimatisation was often presented as a significant, exciting, and new aspect of ‘practical distribution-based natural history’, where ‘commerce, colonialism and scientific enterprise intersected dramatically’.Footnote 59

British naturalists were particularly optimistic about the acclimatisation potential of Chinese species, such as Reeves’ pheasant, due to the similarities in climate that they perceived to exist between Britain and China in spite of their geographical distance.Footnote 60 Gould, for instance, expected the species ‘to breed in and ornament our aviaries for many years to come’, adamant that ‘there can be little doubt; for its native country, the neighbourhood of Pekin, and the British Islands being nearly in the same parallel of latitude, our climate cannot be an uncongenial one’.Footnote 61 Reeves’ pheasants first bred at Regent’s Park in 1848, with four more instances occurring between then and 1868, when twenty-one Reeves’ pheasants were raised from hatchlings, with a further six chicks being reared in 1870. These additions were widely celebrated by the ZSL as valuable contributions to its stock of rare and exotic birds and, by 1869, Reeves’ pheasant could be found in most British zoos and private aviaries.Footnote 62

Reeves’ pheasant: an ideal gamebird

As battue shooting rapidly developed and proliferated throughout Britain during the nineteenth century, the pheasant, rather than the partridge, became the game bird of choice for the new model of shooting estate that emerged during this period and landowners became increasingly eager to obtain and experiment with exotic pheasant species from India and the Far East.Footnote 63 As wealthy landowners formed the core demographic of the acclimatisation movement, it is not, therefore, surprising that particular attention was paid to the naturalisation of species with sporting potential, a focus that was maintained by amateur ‘gentlemen breeders’, even when there was less interest from institutions, such as the ZSL and the ASGB, the latter being disbanded in 1869.Footnote 64 Within this context, Stone was the first to speculate on the potential of Reeves’ pheasant as an excellent game bird, stating that it would ‘afford the best sport of all the pheasants, and from the size and magnificence of its plumage… [would] be a desirable addition to our list of game birds’.Footnote 65, Footnote 66 Stone’s desire was ‘to see Reeves’s pheasant common on the dinner-table’, a sentiment that stemmed not only from its increasing availability and affordability in Britain but also from reports to the ZSL of new British encounters with the species in the Pekin markets, where it was being sold for food on account of its ‘very delicious’ flavour.Footnote 67

Although the ASGB had been particularly interested in propagating Reeves’ pheasant, it never acquired enough specimens to attempt any serious experiments.Footnote 68 However, in 1870, the prominent politician and sportsman, Lord Tweedmouth, made the first attempt to naturalise Reeves’ pheasant in Britain by releasing a pair of birds, imported directly from China, onto his estate at Guisachan, Inverness-shire.Footnote 69 The birds bred quickly, with twenty being reared in the first year, and the species was well established on the estate by the mid-1890s, a fact that many nineteenth-century enthusiasts and naturalists cited to demonstrate the species’ acclimatisation potential.Footnote 70 Indeed, during this period, Reeves’ pheasant naturalisation attempts took place across Scotland, at sites including the Balmacaan estate, in Inverness-shire, Duff House and Pitcroy in Aberdeenshire, Tulliallan in Fife, Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute, and in Kircudbrightshire.Footnote 71 These successes supported Stone’s earlier belief that Reeves’ pheasant ‘would thrive in the rough woods of the Scotch hills’ and inspired contemporary naturalists and acclimatisers to predict the species’ impending colonisation of the rest of Britain.Footnote 72

The ornithologist, Ogilvie-Grant, assessed Reeves’ pheasant as being ‘well able to take care of himself in any climate, at any time, at any altitude’, its tendency to fly long distances when startled being a negligible issue ‘in such extensive forest grounds as the highlands of Scotland present’.Footnote 73 Similar attitudes continued to be voiced into the early twentieth century, with the sportsman and naturalist, John Guille Millais, claiming that he ‘could name a hundred localities in Scotland, England, and Wales where Reeves’s Pheasant would be certain to succeed’.Footnote 74 Another sportsman and amateur naturalist, writing in 1913, was so impressed with ‘the readiness with which this beautiful pheasant seemed to adapt itself to our northern preserves’ that he declared it was ‘not much to expect that in a few years it would become thoroughly naturalised, and be found in considerable numbers all over the country’.Footnote 75

The success of these initial introductions did much to cement imaginings of Reeves’ pheasant as a suitable candidate for naturalisation on shooting estates, these new sites of encounter serving to reaffirm its status as an ideal game bird. This construction of Reeves’ pheasant, as a good sporting bird, was propagated and communicated to a broader audience through works, such as William Tegetmeier’s Pheasants: Their Natural History and Practical Management, first published in 1878. As the historian of science, Karen Sayer, points out, Tegetmeier, a prominent naturalist and fancy enthusiast, was especially interested in assessing the utility of introduced animals as a form of ‘practical naturalism’, an approach that resonated with ‘wider imperialist conceptions of science that used it as a tool to explore and develop the Empire’s natural resources… [that] could be brought home to the farm and the fancy’.Footnote 76 Consequently, Tegetmeier’s description of Reeves’ pheasant drew on new encounters with the bird on British shooting estates to assess its useful qualities and evaluate its potential.

Tegetmeier explained, quoting from an 1877 letter from the head keeper of the Elvedon estate, which belonged to Maharajah Dhuleep Singh, that the sporting value of Reeves’ pheasants lay ‘in their being good raisers, and their being stronger on the wing and flying higher than the common pheasant’, the former showing ‘decidedly better and finer sport’ and being a ‘much nobler’ bird.Footnote 77 As Tegetmeier had a broader interest in cross-breeding, as a way of improving domestic stock, he also highlighted the hybridisation potential of Reeves’ pheasant, acknowledging that the crosses produced between Reeves’ pheasant and the common pheasant at the Elvedon estate were ‘remarkably fine birds, both as regards size and plumage’.Footnote 78 However, he concluded that Reeves’ pheasant hybrids were still quite inferior to pure-bred birds as they lacked both the ‘the splendid golden yellow’ plumage and the steep flight trajectories of their sires.Footnote 79

Praise for Reeves’ pheasant as a sporting bird also grew as British sportsmen were increasingly able to participate in shooting the species in its native range, the evergreen forests of the Chinese interior. In an article published in the Field magazine in 1886, for example, E. F. Creagh, the Foreign Customs Official for South Taiwan in 1885, recounted his experience of shooting the species in China, noting that ‘when taken by surprise, they [Reeves’ Pheasants] rise, and then only by great caution can a single sportsman hope to get them’, the difficulty in ‘bagging’ these ‘splendid birds’ reinforcing their appeal as ideal game birds for accomplished sportsmen.Footnote 80 As one of only a few observations of Reeves’ pheasant in the wild, this article was frequently quoted at length by nineteenth-century British naturalists, such as Ogilvie-Grant, which helped to propagate a glowing assessment of the bird’s sporting qualities.Footnote 81 These depictions mirrored reports from sportsmen on shoots in Scotland, with Millais reflecting, following his experience at Guisachan in 1890, that amidst ‘country which must to a great extent resemble the true home of the bird in question… as soon as one of the long-tailed sky-rockets cleared the trees, he… came forwards at a pace which was little short of terrific’.Footnote 82 Clearly impressed by his experience, Millais explained that these features were ‘all that the sportsman wants… a bird of unrivalled beauty, and unequalled pace, which practically fulfils all the conditions which the modern shooter requires’.Footnote 83

By the late 1880s, Reeves’ pheasant was frequently being presented as the perfect bird for any estate, with descriptions emphasising its admirable combination of beautiful plumage, spectacular tail feathers, irregular flight pattern, and delicious taste. The fancy enthusiast, George Horne, declared, in his 1887 work, Pheasant Keeping for Amateurs, that Reeves’ pheasant was ‘undoubtedly the noblest of our pheasants’, these ‘truly majestic birds… an ornament to any estate’, adding that a flock of such birds on an estate ‘would elicit the admiration of all, one would hardly have the heart to shoot them’.Footnote 84 In spite of this sentiment, he continued that ‘those who have tried breeding with Reeves’ pheasant in this country, say they are the “pheasant of the future,” and that they are well suited to our coverts’, being ‘true “rocketers,” and excellent sporting birds’.Footnote 85 Horne further asserted that he wanted ‘to see greater efforts made to introduce them… all over the United Kingdom’, stating that ‘it would be impossible to speak too highly of these noble birds and those who have room will find but little trouble in rearing them’, concluding that the more he saw of Reeves’ pheasant, the better he liked it.Footnote 86

By the end of the nineteenth century, Reeves’ pheasant was frequently being presented in popular publications as the ultimate pheasant, with one article, published in The Spectator in 1897, proclaiming it the ‘king of pheasants’.Footnote 87 Stating that Reeves’ pheasant was unique and would excel in any role, the article described its beautiful plumage in great detail to show that there was ‘no known bird, not even a peacock’ that looked ‘quite so splendid on the wing’.Footnote 88 It further commented on ‘the astonishing beauty’ of hybrids of Reeves’ pheasant and the common pheasant, challenging Tegetmeier’s earlier misgivings by speculating that these hybrids ‘would be an ideal bird for our coverts… an improved common pheasant, much larger and handsomer’.Footnote 89 Citing the successes at Lilford Hall, the Northamptonshire estate of Thomas Littleton Powys, 4th Barron Lilford, the article presented Reeves’ pheasant as ‘hardy and easy to rear’, declaring that the acclimatisation of ‘so splendid a bird’ on British estates was ‘a triumph of British enterprise’.Footnote 90 Although it begrudgingly admitted that it might be some time before the species would become ‘a “common object” of the dinner-table’, the article used Lilford’s endorsement of the species as ‘excellent for the table, far superior to the common pheasant’ to support its claims that Reeves’ pheasant was ‘the best in flavour of all the pheasants of China’.Footnote 91 It triumphantly concluded that the presence of Reeves’ pheasant in British aviaries and on shooting estates was exactly ‘what Mr. Stone [had] anticipated’, with those observing ‘the size, gorgeous colour, and enormous tails of his [Stone’s] “seven-foot” pheasants’ declaring them ‘an enthusiast’s dream’.Footnote 92

Reeves’ pheasant: out of favour and in decline

During the 1880s, as encounters with Reeves’ pheasant on British shooting estates increased, British naturalists, acclimatisers, sportsmen, and pheasant fanciers began to observe new behaviours that directly challenged contemporary conceptions of the species as the ‘pheasant of the future’. The species was first noted to act aggressively towards other pheasants within the covert, with the amateur naturalist, Robert Gray, observing in 1881 that two of the Reeves’ pheasants on the Elvedon estate had been shot ‘on account of their pugnacity’.Footnote 93 By the turn of the century, the species’ feisty nature had become one of its defining characteristics, with the fancy enthusiast, Frank Finn, highlighting in his 1901 work that male Reeves’ pheasants possessed a tendency to aggressively ‘drive away the ordinary Pheasants’ if kept in mixed coverts.Footnote 94 Indeed, as the twentieth century progressed, this aggression towards other pheasant species, observed in male Reeves’ pheasants, was increasingly cited by naturalists, sportsmen, and enthusiasts as one of the key reasons for its failure to spread across Britain.Footnote 95

Male Reeves’ pheasants were also observed to widely disperse from their release sites, making it difficult for estate owners to maintain stable populations of the species without introducing new birds.Footnote 96 Lord Lilford highlighted this issue in the second edition of his Notes on the Birds of Northamptonshire and Neighbourhood, published in 1895, noting that Reeves’ pheasant possessed ‘the roaming instinct in a still higher degree than the Ring-necked species’ and was, therefore, ‘not a desirable bird, from a sporting point of view, except in very large ranges of woodland’, such as those found in Scotland.Footnote 97 The sportsman, Captain Aymer Maxwell, writing in 1913, concurred, arguing that Reeves’ Pheasant had ‘no place in the game-coverts of the low country’ as it would ‘either wander beyond the narrow confines of the home allotted to him’ or ‘stay at home to drive away the other pheasants’.Footnote 98 Indeed, attempts to acclimatise Reeves’ pheasant in England during the late nineteenth century, at sites in Northamptonshire, Bedfordshire, Gloucestershire, and Kent, all failed, with only the population in Bedfordshire enduring ‘for any length of time’.Footnote 99

Owing to these failures, naturalists and enthusiasts came to view the Scottish estates as the only places in Britain where these exotic pheasants could really thrive, with Finn, for instance, predicting that, although the bird was ‘likely to become more popular’ in Britain, it ‘should only be turned out in hilly, broken ground with heavy undergrowth’.Footnote 100 Millais, writing almost a decade later, also reflected that Reeves’ pheasant had ‘never become a general favourite in our islands, owing to the fact that only limited areas… [were] suitable to its habits and disposition’, adding that ‘to enjoy the surpassing beauty of this species the naturalist must see Reeves’s Pheasant in perfect freedom, and on ground similar to their natural habitat’, a spectacle that could only ‘be witnessed properly… at Guisachan’.Footnote 101 Maxwell also described Reeves’ pheasant as ‘a mountain dweller, a bird of rough hill wood and rugged places’, that only did well where ‘the natural features are all on a large scale, and rough woods of wide extent clothe the open hillsides’, a place where ordinary pheasants ‘would not thrive’.Footnote 102

In spite of its perceived limitations, many sportsmen and enthusiasts continued to present Reeves’ pheasant as a good game bird, with Finn describing the species as ‘eminently suited’ to the role as it was ‘very showy, a very rapid flyer, and excellent for the table’.Footnote 103 Barton similarly praised the species’ ‘remarkably vigorous’ flight, explaining that it was ‘a difficult bird to shoot until the sportsman… [became] an adept in the art of shooting these Pheasants’.Footnote 104 Barton and the naturalist, William Beebe, both reinforced the species’ sporting prowess by quoting extensively from Creagh’s 1886 article on the shooting of Reeves’ pheasants in China, their assessments generally enduring into the twentieth century.Footnote 105 The game bird credentials of Reeves’ pheasant were also maintained through frequent references to its excellent flavour, across a range of works, including the writings of Lord Lilford, guidebooks for zoological gardens, and zoological publications on pheasants.Footnote 106 Indeed, as Reeves’ pheasant was observed to occupy and breed well in habitats that the common pheasant struggled to colonise, notably the large, heavily forested estates in the mountainous areas of Britain, it continued to be regarded as a valuable addition to national game stocks.Footnote 107

Although writers continued to praise the ornamental qualities of Reeves’ pheasant to support calls for its naturalisation in Britain, its reputation as an ideal aviary bird was also increasingly challenged by fanciers who were finding it difficult to preserve the bird’s extremely long tailfeathers in a captive environment.Footnote 108 Finn, for instance, pointed out that ‘the length of this bird’s tail makes a large space necessary if that appendage is to be kept in show condition, and so it is less suitable for amateurs than most other species, in spite of its great beauty and very unique appearance’.Footnote 109 Indeed, with naturalists and fanciers reiterating this advice well into the twentieth century, these birds generally remained confined to the collections of specialist breeders and enthusiasts, who were able to provide sufficient aviary space and the expertise to deal with the persistent issues surrounding the preservation of male Reeves’ pheasant tailfeathers.Footnote 110

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Reeves’ pheasant numbers were noticeably in decline in Britain, with contemporary sportsmen particularly commenting on the profound effect of the collapse of the Guisachan Reeves’ pheasant population following the sale of the estate in 1905.Footnote 111 The waning interest in pheasant shooting in Britain around and after the First and Second World Wars, and the subsequent dismantling of many shooting estates, also prevented the recovery of Reeves’ pheasant populations, which like other exotic pheasants, continued to decline.Footnote 112 Faced with rising costs and little interest in acclimatisation projects, shrinking populations of introduced exotic pheasants were often abandoned by landowners, who were not inclined to maintain them or establish new populations.Footnote 113 Whilst some attempts were still made to naturalise Reeves’ pheasant in Britain, such as at Elveden Hall, Suffolk, in 1950, in Cumberland, now part of Cumbria, in 1969, and in Kinveachy Forest, Inverness-shire, in 1970, these sporadic releases had little impact on the bird’s declining numbers.Footnote 114

With a growing awareness, since the 1890s, of the damage that invasive species can cause, the introduction of non-native species into Britain has been increasingly questioned, culminating in the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981, which now prohibits the release of any non-native species into the British countryside.Footnote 115 As Reeves’ pheasant was listed as one of the species unequivocally covered by this new legislation, owners are now obliged to destroy any unwanted birds.Footnote 116 Consequently, the few, small, and scattered populations of Reeves’ pheasant that still exist in today’s British countryside are likely to be the products of earlier naturalisation attempts on country estates, illegal releases, or birds that have escaped from captivity, its breeding status in the United Kingdom currently listed as ‘unconfirmed’.Footnote 117 Once admired and desired, Reeves’ pheasant, like many other introduced exotic pheasants, is now considered by some to be ‘out-of-place’ in Britain because its showy and extravagant plumage does not ‘look right’ in the British landscape.Footnote 118

Conclusion

This study demonstrates how the presence of Reeves’ pheasant in Britain was shaped by imaginings of the species, by naturalists, acclimatisers, fanciers, and sportsmen, whose encounters with this bird were informed by the spaces in which they occurred and the broader, nineteenth-century, imperial context. As new information on Reeves’ pheasant became available, through increasing interactions with specimens at new sites of encounter, constructions of the species evolved to include new paradigms that reflected particular interests and aspirations, expressed through new emphases on the bird’s status, defining features and characteristics. Eighteenth-century naturalists first constructed the theoretical species, P. superbus, as a mysterious, beautiful, rare, and valuable bird, with brightly coloured plumage and a long, magnificent tail, in response to depictions they had encountered on high-quality Chinese goods. In the early nineteenth century, the arrival of Reeves’ pheasant tailfeathers in Europe confirmed the existence of a real bird with a magnificent tail and, following the arrival of complete specimens, detailed descriptions of its full, beautiful plumage began to emerge. The bird’s ornamental qualities were reaffirmed through reports of physical encounters with Reeves’ pheasant in British aviaries in China that mimicked the practices of the wealthy Chinese. Owing to restrictions on European access to China, Reeves’ pheasant specimens, which were difficult to obtain, were largely sourced from Chinese markets and transported to Britain, like other Chinese goods, via imperial trade networks, which encouraged the species to be similarly presented as a valuable, rare, and exotic commodity.

Following the naming of Reeves’ pheasant by John Gray, in 1829, and the presentation of the first live specimen in Europe to the ZSL, by John Reeves in 1831, naturalists, enthusiasts, and acclimatisers, drawing on earlier works, characterised Reeves’ pheasant as an excellent and desirable, ornamental bird for British aviaries and estates. These descriptions continued to place a strong emphasis on the bird’s magnificent plumage and tail feathers, reiterated that the wealthy Chinese kept them in aviaries and favourably compared them to other, highly-regarded exotic pheasants already in Britain. During the 1860s, more information about Reeves’ pheasant began to arrive in Britain through a network of correspondents with strong links to the ZSL and the ASGB, owing to Britain’s developing, informal empire in China. By the late 1860s, as the number of specimens in Britain increased and a captive population was established, aspirations for the acclimatisation of Reeves’ pheasant, as an aviary bird and a game bird, began to emerge in Britain. By the late nineteenth century, sportsmen were hailing its excellent game bird potential, noting its unique flight pattern, speed, size, beauty, and delicious flavour. These imaginings quickly gained traction, being driven by the strong interest of acclimatisers in the sporting potential of introduced species and the growing popularity of pheasant shooting in nineteenth-century Britain.

As Reeves’ pheasant proliferated in Britain and attempts were made to naturalise it on shooting estates, encounters with the species in these new environments helped to consolidate its status as an ornamental game bird and high expectations were placed upon it as the ‘pheasant of the future’ and the ‘king of pheasants’. In spite of these accolades, some new observations of the species in the 1880s and 1890s began to contest its status as an ideal game bird. Reeves’ pheasant was increasingly observed to be pugnacious, with a tendency to drive away other pheasants if placed within a mixed covert. It also dispersed too far from its release site and early naturalisation attempts in England largely failed, confining it to the mountainous hill-forests of Scotland, where it could still thrive. Although some ornithologists and sportsmen still presented Reeves’ pheasant as a hardy, good-sized, beautiful bird, with magnificent tailfeathers and a high and rapid flight pattern, its population significantly declined in Britain during and after the First and Second World Wars, owing to a decreasing interest in pheasant shooting and the dismantling of many shooting estates. With growing concerns regarding invasive species, the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act was passed, making it illegal to release any more Reeves’ pheasants into the British countryside.

These findings usefully illustrate how new textual and physical encounters with Reeves’ pheasant in Britain and China directly influenced how naturalists, enthusiasts, fanciers, and sportsmen imagined and constructed the species. Each site of encounter, owing to its particular nature, provided specific opportunities and limitations that determined how Reeves’ pheasant could be observed within that space and, consequently, what kind of information could be collected. Over time, encounters with Reeves’ pheasant changed, from early interactions with depictions on high-quality Chinese goods to analyses of tailfeather commodities, to observations of live specimens in Chinese and then in British aviaries, to experiences on shooting estates in Britain and the Chinese interior, with new sites of encounter often emerging as a result of broader national developments and international events. Observations stemming from these encounters with Reeves’ pheasant were also assessed within a broader framework of contemporary, British beliefs, preoccupations, and desires, which collectively informed constructions of the species, its status, and its presence in Britain.

Chinese restrictions on European access to China limited encounters between late-eighteenth-century, European naturalists, and Reeves’ pheasant to tantalising depictions on luxury Chinese goods, which encouraged them to directly transfer the qualities of these high-status objects into their constructions of the species as beautiful, rare, valuable, mysterious, and exotic. When the first Reeves’ pheasant tailfeathers entered Europe, as rare and expensive commodities acquired from the Canton markets, they reaffirmed their understanding of the species as a rare and valuable object. Later, encounters with live Reeves’ pheasants in British aviaries in China reinforced imaginings of the species as a splendid, ornamental aviary bird, so that early specimens arriving in Britain were instantly admired for their aesthetic qualities and deposited in aviaries. Descriptions of the species, based on aviary encounters, consistently emphasised the unique and spectacular beauty of the bird’s plumage and its exceptional tailfeathers. Within this context, imperial trade networks were centrally important for the successful transportation of Reeves’ pheasant specimens to Britain, which helped to maintain understandings of the species as a beautiful, desirable, and valuable commodity.

As Britain’s informal empire in China grew during the nineteenth century, new sites of encounter emerged, such as the Pekin markets and the forests of the Chinese interior, which allowed British naturalists, officials, and sportsmen to observe Reeves’ pheasant in new contexts and encouraged them to conceptualise it as a product of empire. With increasing access to China, enthusiasts and diplomats were more able to transport live specimens to Britain, which helped to establish a stable, captive Reeves’ pheasant population and, owing to the growing interest in acclimatisation, British observations of the species were quickly translated into speculations on its usefulness as a game bird and its suitability for naturalisation in Britain. Consequently, Reeves’ pheasant acclimatisation experiments began to take place on shooting estates, with early observations in this context emphasising its game bird qualities, notably its speed, flight pattern, and flavour, information impossible to observe in an aviary setting. The bird’s ideal game bird status was also reinforced through new, favourable, British encounters with the species in its home range in the forests of the Chinese interior.

However, further encounters with Reeves’ pheasant on British shooting estates began to reveal behaviours that challenged its ideal game bird status, notably its aggressive behaviour towards other pheasants, which rendered it unsuitable for mixed coverts, and its wide dispersal range that confined it to the mountainous expanses of Scotland. Later observations of Reeves’ pheasant in British aviaries also revealed that its long tailfeathers could only be kept in perfect condition if accommodated in very large enclosures, a situation that confined it, conceptually and practically, to the aviaries of experienced specialists. In light of these negative observations, Reeves’ pheasant was no longer hailed as the ‘pheasant of the future’ and gradually fell out of favour. Amidst the abandoning of acclimatisation aspirations, a diminishing pheasant-shooting culture in Britain and growing concerns regarding the introduction of non-native species, Reeves’ pheasant numbers rapidly declined during the twentieth century, leaving only a few, scattered descendants to be rarely encountered in the British countryside.