Introduction

England, as is well-known, occupies a unique position among European states in terms of the financing of poor relief from taxation. While rate-based welfare provision began to achieve a degree of national coherence from at least the late seventeenth century, this does not mean that there was a simple progression from voluntarism to state welfare, as the dataset derived from Brougham commission reports (1819–37) and the Digest of Endowed Charity (PP, 1867/8–1877) suggest. Rate-based poor relief and the charitable safety net for those who lacked alternative support frequently interacted and overlapped in a complex variety of ways across the centuries,Footnote 1 and one key element of the latter was charities endowed with the income from landed property. This field of study owes much to the research and writing of Sara Birtles who, in her pioneer article, highlighted how the poor’s allotments in Norfolk and elsewhere established by enclosure awards assisted the poor in two main ways. Parcels of land could be used directly, by the poor themselves; or they could be leased out to raise money for poor relief. These benefits were designed to ‘encourage good behaviour and personal industry among paupers’, to lessen their dependence upon the parish and ease the burden of taxpayers.Footnote 2 The range of charity lands in early modern England is bewildering, but it is possible to make a few generalisations. In the case of disafforestation of royal forest, for example, the charity lands were allocated to the poor to generate incomes for poor relief in lieu of such use-rights as grazing or cutting fuel on the commons.Footnote 3 In Brill and Oakley (Bucks.), the charity land was initially used as an agistment ground by the poor but by the 1680s it was being let to yearly tenants and the income distributed as cash among the poor.Footnote 4 In the case of Slaidburn (Yorks., West Riding), the charity land was used in a combination of ways; partly let, to generate income for the poor and partly used directly by them, under an arrangement akin to agistment by those among them who could pay ten shillings for grazing in summer.Footnote 5 As previous studies have shown, however, the charity lands allotted as compensation for the loss of use-rights to commons were not necessarily or solely limited to the poor who had formerly exploited them. Occasionally they were used, in one or both of these ways, to relieve the poor more generally. Those in authority in a parish sometimes sought to use such land to mitigate the burdens on the rate-payers and thus charity might have served as a subsidy to the poor rate rather than being used for grazing cattle, as the founders of the charity lands would have wished. In consequence, it has been argued that these processes not only changed the poor from active users of the land to parish pensioners, dependent on cash doles from the community, but also instilled within the poor the charity’s ‘immense cultural value’, symbolising their incorporation into the parish community via ‘charities of subordination’.Footnote 6

Yet good governance of charity lands that continued for centuries must have rested on finding the right balance between the necessary trust given to the trustees and the distrust of the poor which required the trustees to scrutinise and constrain any attempts to abuse that trust. By focusing on a detailed case study of ‘charity land’ in the Wiltshire parish of Mere, this paper attempts to analyse how the trustees managed to cope with the balance between the limited charitable funds at their disposal and the increasing/changing demands of the poor during the period between 1650s and 1730s. There was a public desire to scrutinise how the charitable funds had been spent,Footnote 7 and this article will discuss how the amount and types of payment that recipients received shifted over the period studied and how the spectrum of relief was adjusted to reflect the massive macro-level changes of chronic seasonal underemployment or labourers’ improving standard of living that occurred between c. 1660 and c. 1760. These underlying trends occurred in a period of a growing consensus about the ‘utility of poverty’.Footnote 8 While there are obvious dangers in concentrating on a single parish, it is of crucial importance, as French suggests, to engage very closely with a particular place over a sustained period of time.Footnote 9

This paper employs a dataset derived from an account book for charitable funds that encompasses all payments made to named individuals within the Wiltshire parish of Mere between 1656 and 1739. These total 3,089 payments to 713 recipients consist of 476 male labourers, and 237 widows and single women. Analysis of this dataset provides new insights not only into the size, scope, and significance of parochial charitable welfare, and changes in these over time but also illustrates the inextricably mixed character of welfare provision – the balance between the different financial resources available both to formal relief and parish charities – which arose in Mere.Footnote 10 It is important to avoid overgeneralisation, yet, in data derived from the whole period 1819–38 covered by the Brougham Reports, Mere’s level of provision in cash per capita (two shillings) was equivalent to the median (2.0 shillings) available from the aggregation of charities reported, and very close to the mode (1.0 shilling) of 119 samples that can be observed in the Report. This suggests that the findings from a detailed consideration of this parish could be applicable elsewhere.Footnote 11

In the following discussion, section two briefly illustrates the socio-economic background of Mere, especially as a smaller, de-industrialising, centre of linen production, embedded within a predominantly rural economy. This analysis draws on evidence from wills left by residents of Mere in the period 1658–1739. In the third section, I will discuss how the local authority attempted to cope with the increasing economic polarities in rural society by providing the poor who could not receive rate-based parochial relief with the cash payments available from the ‘charity land’ as an alternative form of welfare. Section four will address how the micro-level provisioning to each category or gender of applicants shifted in response to economic macro-level changes.

Local economy, proto-industry and poor relief

Mere parish, situated in the south-west of Wiltshire, included the administrative subdivisions of Mere town, Chaddenwicke, Woodlands and Zeals tithings. They lay in a clothing and dairying region, encompassing about 7,400 statute acres and with a population of 2,091 people in 1801. Land was divided among small family farms and cloth-making sustained the members of the family who would not otherwise have been fully employed. There were dense connections between the industrial and agrarian sectors in such areas.Footnote 12 Mere bordered on the ancient royal forest of Gillingham, so the pre-disafforestation population enjoyed ‘freedom and liberty’ for their commonable cattle (except sheep), for which they had paid a yearly rent to the manorial lord of Gillingham (Dors.), called ‘Common silver’. They were granted 200 acres of land as compensation for their common rights after disafforestation, and of this, 80 acres were allotted as a compensation for the loss of use-rights to the common that the poor had previously enjoyed. The land was conveyed to thirteen chief inhabitants (later called the ‘Company’) as trustees who managed the forest charity.Footnote 13 The charitable funds derived from the land were used in such ways as grants of small sums to the poor, interest-free loans made to poor tradesmen, and substantial payments made to bind out poor children.Footnote 14 This continued until 1905, when the 80 acres were let to the tenants at £135, of which about £114 was distributed among 509 eligible recipients at 4s. 8d. per household.Footnote 15

According to the survey of the demesnes of Mere manor in 1650, there were about 163 acres of pasture or meadow lands, almost 337 acres of arable and 126 acres of heath and woody lands. The parliamentary survey of 1651 allows an estimate of population and social structure, suggesting a high proportion of cottagers and landless people.Footnote 16 Although such surveys do not generally include tenants of cottages newly erected on manorial waste who were holding ad placitum (24 households), the one exception to this rule is the Mere parliamentary survey of 1651.Footnote 17 Given that 15 acres was too little land to be a commercially viable farm sufficient to support its owner,Footnote 18 the extent of poverty in Mere, where there might have been at least 65 such copyholders (50 of whom held under 5 acres), was potentially considerable. These households might have been engaged in other economic activities, such as cloth production. If we estimate the numbers of the above-mentioned cottagers with ad placitum in line with such copyholders, the proportion of cottagers and landless people could have amounted to at least 70 per cent of all households. In such a region of mixed farming and textile production, some of the labourers with low levels of income made ends meet by supplementing agricultural work with spinning or weaving.Footnote 19 Thomas Bourne (d. 1701), husbandman, for example, left goods valued at £27, without any agricultural working tools, but he held two looms, three turns, and one warping bar and skerm in his outhouse.Footnote 20 Similarly, the inventory of William Ribb (d. 1706), husbandman, itemised goods valued at only £5. 3s. 6d., without any agricultural tools, yet including one loom.Footnote 21 On the other hand, William Harding (d. 1683), yeoman, left an inventory valued at £256, itemising about £57 of crops in the form of 21 acres of wheat and 25 acres of barley, and almost £86 worth of livestock, i.e. one hundred and seventy-five sheep plus £39 worth of other animals (including 6 oxen, 2 horses, 2 mares and a colt). On May 2 in the following year, Jane Harding, his administrix, discharged his obligations of several payments for ‘reeping the corne’, valued at £2. 16s, ‘moeing and greeping’, valued at £1. 14s., and for the ‘workmans wages’, valued at £10. 8s., etc. Thus, he almost certainly employed labourers, either part-time or full-time.Footnote 22

Meanwhile, by the early eighteenth-century, small-scale domestic production was proto-industrialised in Mere, comprising household by-employment, often for local markets, and this continued until 1837.Footnote 23 During the years 1661–1738, 37 linen weavers can be identified in the probate inventories, some of whom acted as manufacturers organising the various stages of preparing the flax, spinning, weaving, and breaching in their own workshops. Most had a smaller proportion of their income related to agriculture, indicating that they were wealthy linen manufacturers almost independent of farming.Footnote 24 For example, in the case of Christopher Alford, his warping loft was equipped with a warping bar and skarme, and his workshop had two spinning wheels, ‘two Spooling Turnes’, two wicker hangers (‘two Swifts’), three brush cards (‘three Hatchells’), two looms, and the looms had linen pillowcases in the process of being woven. His total inventory was valued at £39. 15s., itemising linen yarn and flax.Footnote 25 On the other hand, John Fleet (d. 1702), weaver, left his inventory valued at only £12., including one loom and 78 pounds of brown and white yarn valued at £10. 8s, indicating that he was working under the putting-out system.Footnote 26 The probate inventory (£15. 4s. 16d., 1678) of John Pitman, linen weaver, does not mention a loom,Footnote 27 and John Bealing’s inventory (£3. 14s. 2d., 1685) likewise fails to mention one, but he had a warping bar and scum, and a spinning wheel and two cards.Footnote 28 The probate inventory of Susannah Forward (£8. 2d. 3d., 1692), spinster, (literally meaning a spinner), does not mention the tools and materials relating to spinning. Also, that of Frances Birt (£7. 13s. 6d., 1663), spinster, had ‘one toune’, only a spinning wheel.Footnote 29 Mary Hartgill (d.1741), spinster left an inventory valued at only £5. 16s. 11d., including ‘woollen turn’ valued at 1s.Footnote 30 It seems likely that these latter testators were poor linen weavers and spinsters, who were either engaged in a small-scale manufacture or employed under the putting-out system.Footnote 31

Wealthy linen clothiers thus undertook all processes, from growing flax to bleaching and spinning yarn, by hiring many waged workers, partly outsourcing the spinning and weaving processes, to produce linen yarns and manufactured goods (mainly tick and dowlas) for local markets.Footnote 32 But, as John Walter’s sophisticated analysis suggests, this means that weavers were not simply divided between rich clothiers and poor weavers, but rather multiple people branched out into the organisation of production.Footnote 33 In any case, spinning was a valued source of employment and income for impoverished and otherwise underemployed women and children in this region. Thus, these findings support and amplify Muldrew’s research on the increasing scale of home linen production in the seventeenth century.Footnote 34 The wealthy linen weavers were not, however, industrial capitalists on any great scale, so although poor linen weavers were dependent upon them, they were not tied to a single manufacturer, and retained control of their looms and their working day. They were embedded within a predominantly rural economy and society, and they could be considered as smallholders or farm labourers. For this reason, it is necessary to view Mere’s manufacturing society in the context of its agricultural economy and discuss how this changed in the period after the 1650s – post-enclosure – and how this in turn accentuated or ameliorated the social divisions of a proto-industrial manufacturing society.Footnote 35 In other words, it is important to discuss how the local authority attempted to cope with the increasing economic polarities in rural society by providing doles from the ‘charity land’.

Alternative welfare mechanisms

Food costs rose from one-third of weekly household income to just under half, and spinning earnings fell markedly from 1730s to the end of the century. These trends ought to have had an impact on both the causes and the regional scale of poverty, which would have forced a change of the relief lists towards certain categories of poor people.

The expenditure of rate-based formal poor relief in Mere amounted to about £350 in 1733, and the payments available from the charity land amounted to only about £45 (so one-eighth of formal poor expenditure).Footnote 36 Thus, the amounts being distributed through formal parish poor relief were much greater than those through the charity land. The 64 poor people who received regular pensions from the parish in this year comprised 24 widows, 19 other adult females, 11 children, and 11 males, amounting to £203. 8s. 2d. in expenditure. The amounts each recipient received may not have been particularly large, averaging 5s per month, which was a relatively common feature of the more general relief landscape.Footnote 37 Pensions comprised 55 per cent of total expenditure in 1733 (£368. 16s. 3d.). The total recipient list was therefore heavily skewed towards women in 1733. If we assume a monthly male/household wage of 26s for the decade 1730–40, the mean monthly relief totals at the same date would suggest that pensions for men (from 3.63s to 4.25s. each) provided around 14–16 per cent of the male wage.Footnote 38 On the other hand, given that 4s a week was considered a normal week’s earnings for an adult spinner in the 1730s, the monthly pensions for widows and single women (from 5.1s to 5.5s per month) were equivalent to slightly above one week’s income from spinning.Footnote 39 However, the social profile of rate-based regular recipients, who were often the least able to support themselves, might be different to those receiving rate-based occasional payment or payments made by the charity.Footnote 40 Likewise, as is well-known, a considerable number of parishes nationwide contributed to the housing supply for the poor before 1780, providing buildings which were dedicated to the care of the aged or disabled, or occupied by the oldest widowed inhabitants.Footnote 41 At Mere, 44 recipients (widows 16, female 15 and male 16) were given money for house rents from the overseers’ account in 1733, amounting to £34. 17s. 2d. per annum - £9.7 for widows (28 per cent), £9.5 for female (27 per cent) and £15.7 for male (45 per cent) – which comprised about 10 per cent of total expenditure.

On the other hand, casual payments in 1733 amounted to £130. 10s. 11d., which comprised almost 37 per cent of the value of annual rate-based formal poor relief expenditure. The distribution of casual expenditure between various payment categories in 1733 suggests that the overseers’ disbursements took the form of direct individual relief provision. They were either non-specified money doles or allowances, or specific sums for administrative expenses such as legal costs for the drawing up of indentures, travel expenses, maintenance costs of the almshouse, the provision of care, and to cover bills for clothing and shoes. Such specified expenditure accounted for almost 80 per cent of the total. The data also suggest that the cost of clothing was substantially higher for children and widows, presumably because these groups lacked the earning capacity to buy clothes and that the cost of sickness was significant for working-age men and women, particularly those with dependent children. The bills for supplying clothing and shoes for the poor, amounting to almost one-third of all payments, were paid to male and female recipients alike, suggesting that they were not the elderly but individuals of working age. There were two types of care costs, namely payments made to doctors ‘for one year’s care of the poor’ and those made to women who were engaged as ‘Bath Woman’, or who provided child care for other people, suggesting that ‘a significant proportion of married and widowed women who took in young children to nurse, supplied the essential economic infrastructure that is childcare, thereby facilitating the productive activity of other women as well as men’.Footnote 42

The unspecified ‘general allowances’ only comprised about 20 per cent of all casual payments. The data suggest that casual cash payments to men were equivalent to about 12.7 per cent of the male monthly wage, and those to women were the same as the weekly wage for adult spinners, if we assume that the elderly of both sexes received the bulk of their relief as weekly pensions, while men and women of working age received cash payments in the form of ‘general allowances’. This explains why the gender balance was different for rate-based occasional cash payments and those available from the charity land, as will be discussed below.

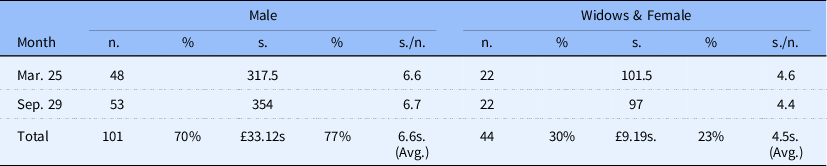

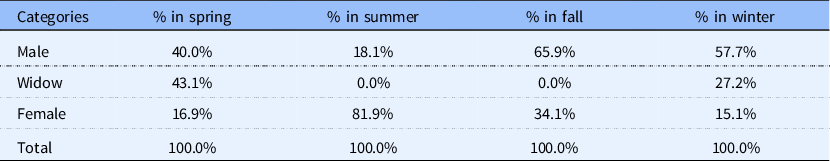

In 1733, 145 recipients received relief from the charity land annually, not much different from the 152 recipients of rate-based occasional cash payments. As Table 1 shows, however, when comparisons with rate-based casual payments are possible, the number and value of payments from the charity land to male recipients were much higher than those made to female recipients, amounting to 70 and 77 per cent, respectively. Seasonality could be an important potential variant in the size and frequency of rate-based casual cash payments. In such a region as Mere, where proto-industry was well established, the labourers are thought to have been involved in wage-dependent agricultural work, when other work was scarce. As Table 2 shows, the proportion of payments to men was relatively high in the autumn and winter seasons, and the proportion of payments to women was rather high in the summer season, because working-age support was the focus of the charity. Nonetheless, the number of male recipients, an average of five or six persons per month, received an average of 3.3s., or 12.7 per cent of the monthly wage of 26s for the decade 1730–40. This suggests that the occasional cash payments made to male recipients did not offer a sufficient welfare package, even if for other groups such payments were equivalent to a weekly working income. This in turn clearly suggests that in Mere, the charity land was an alternative welfare mechanism, which kept people off, or minimised their immediate dependence upon, poor relief. This is a compelling reason why the total recipients were heavily skewed towards men in the charitable trust funds. Thus, almost the same numbers of poor people as were receiving communal relief were probably using charity to remain outside the remit of the communal welfare system by supplementing their income.Footnote 43

Table 1. Forest money payments available from the poor land (1733)

Source: Wiltshire and Swindon History Center, 865/613, Account book of Gillingham (Dorset) forest charity: payments to the poor and sick of Mere out of the revenue from 80 ac. Land late part of the forest with two 19th memoranda of the term of charity, 1657−1739, fols. 155. verso-157. verso.

Table 2. Proportion of cash payments to categories in total value of disbursements of casual payments, Mere (1733)

Source: WSRO, 865/617, Poor rate and overseers’ account and disbursements for one year, for Mere, 1733, 1744.

The charitable funds derived from the charity land were distributed at Lady Day and Michaelmas, when the farmers could decide what number of labourers was adequate for the needs of agriculture.Footnote 44 The amount received per capita each year varied according to the number of applicants and the sum available for distribution.Footnote 45 In other words, the numbers of recipients and payments per capita were affected by the domestic demand, patterns of seasonal production, and the underemployment cycle, plus the market-determined rents paid by the sizeable tenant farmers who leased the charity land.

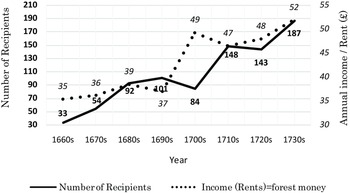

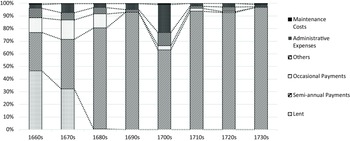

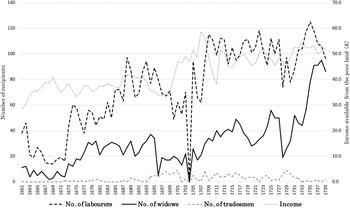

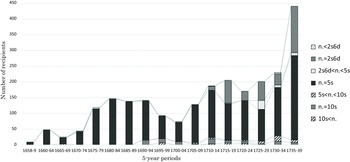

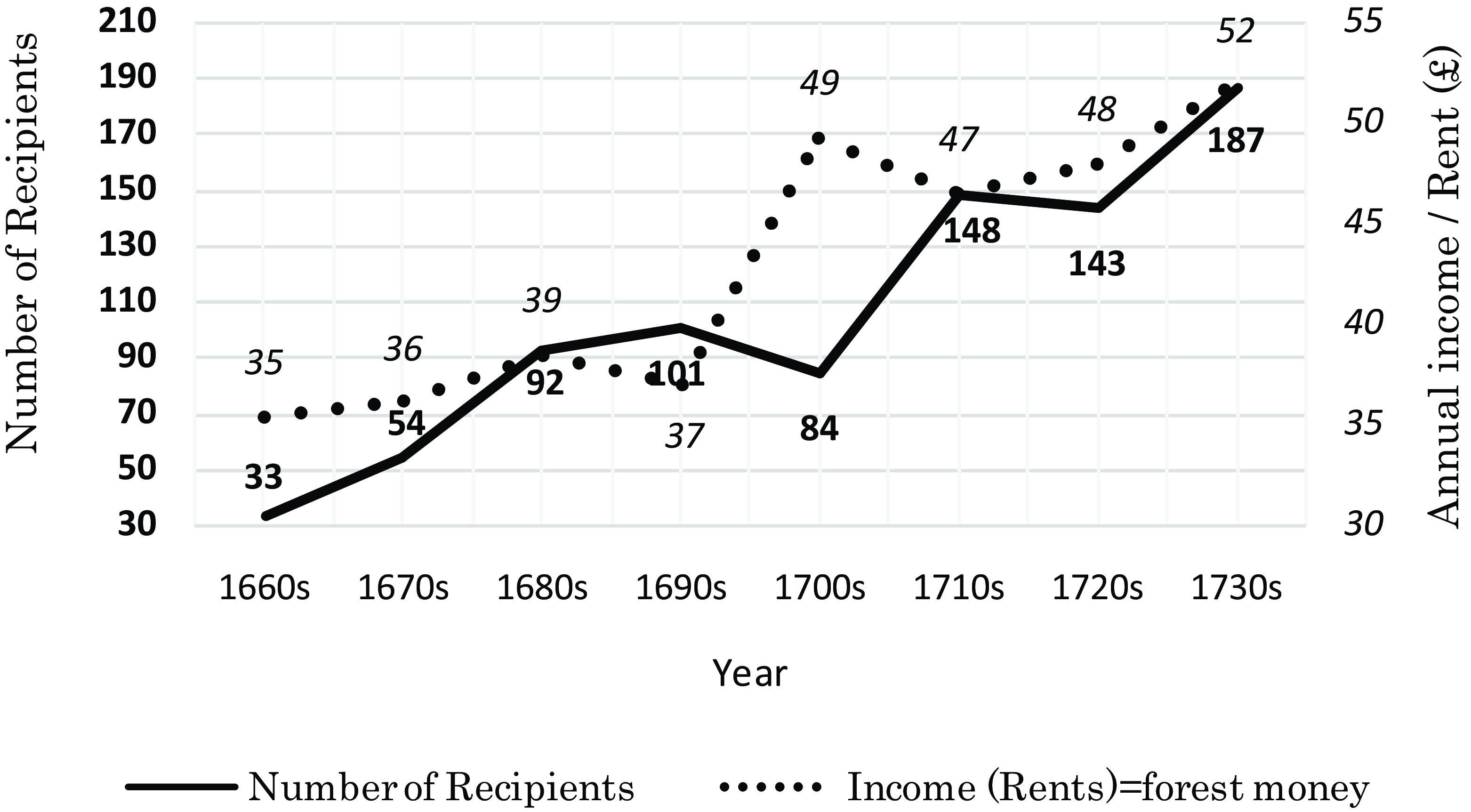

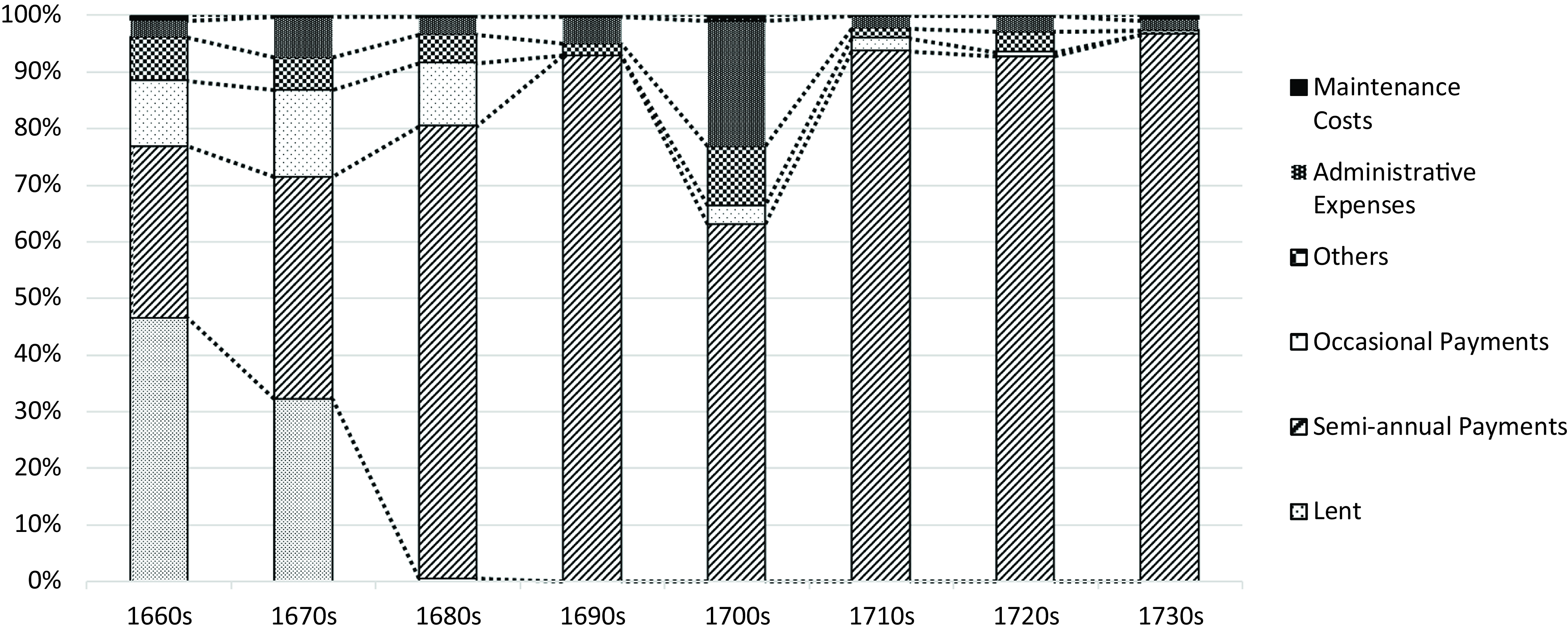

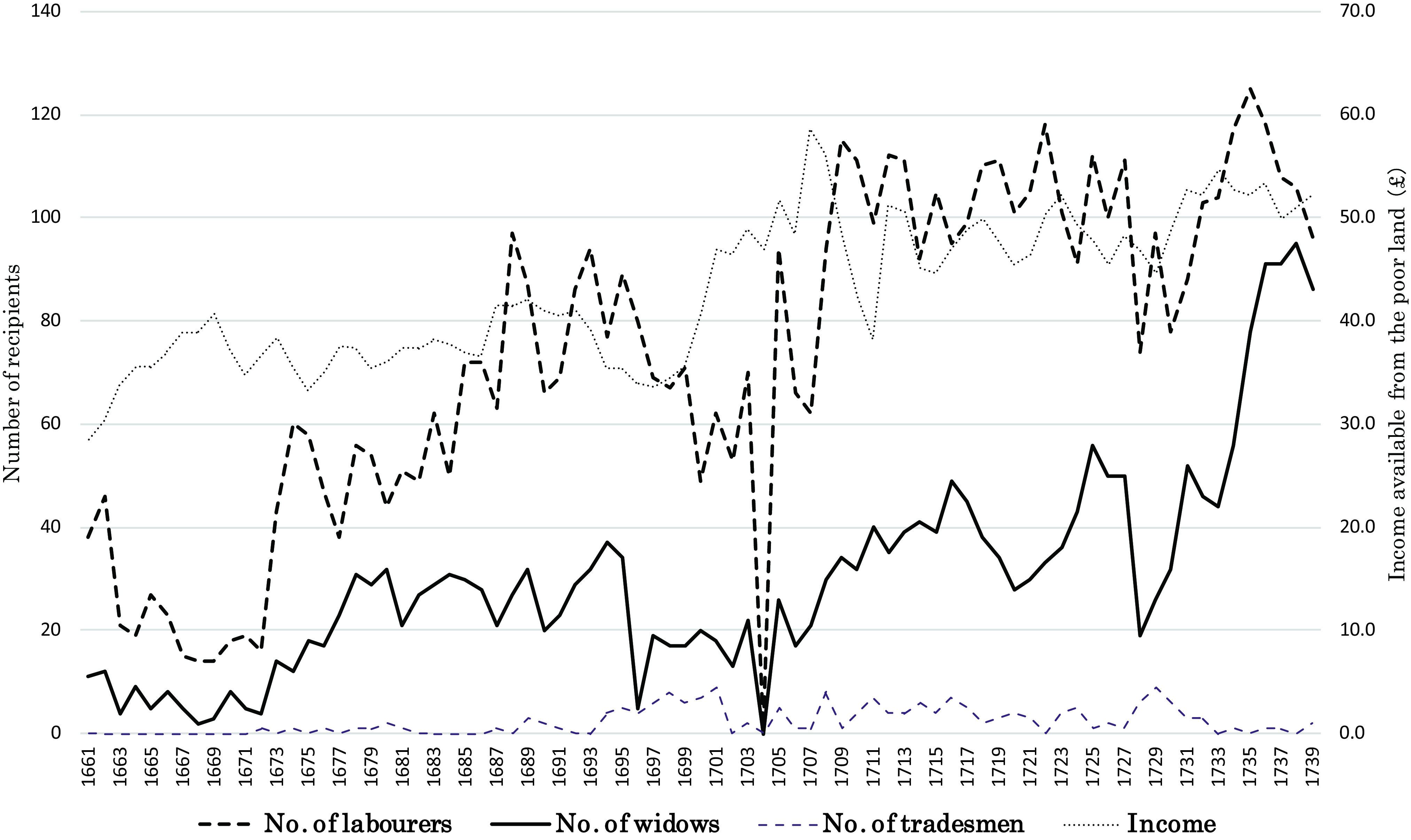

Figure 1 illustrates the total amounts paid to recipients per ten-year period and the number of them, deflated by Mitchell’s average consumer price index during 1660s to 1730s. The sharp rise in the 1700s reflects the shift from £41 per annum of income available from the charity land to £47 from Sep. 29 (1699) onward.Footnote 46 The drop in the number of recipients in the 1700s was due to the fact that in some years the incomes from the charity land were withdrawn to cover legal costs. In the 1710s and 1720s, the number of recipients remained in the 140s, but by the 1730s it had jumped to 187. Figure 2 is based on 8,471 individual payments made by the trustees between 1658 and 1739, and shows the distribution of payments between various recipient categories in each ten-year period. It suggests that the bulk of the trustees’ disbursements were spent on direct individual relief provision, in the form of either specified money doles or loans made to poor (low status) tradesmen, poor labourers and widows; or occasional payments which included specific sums for heating, working tools or equipment, sickness and care costs. The medical and care costs rarely absorbed more than 4 per cent of the total payments, and administrative expenses also rarely absorbed more than 5–7 per cent (except in the 1657–9 and 1700s, when they respectively exceeded 30 per cent and 20 per cent in the context of the Chancery court and the court of Exchequer litigation).Footnote 47 For example, the ‘expenses fees’ (£3.16s.) was appropriated for ‘attendance of the Commissioners upon the ‘Statute of Charitable uses’ at Sarum in 1672.Footnote 48 Likewise, although the payments for pauper apprenticeships accounted for only 5-7 per cent of expenditure between 1660s and 1680s, the size of each payment was substantial, from £1 to £3 per person. For example, in 1687, £2 was given for binding the widow Lander’s son to Henry Clarke, dyer of Mere; while in 1682, William Sanger received £1. 10s. when he took Tayler’s daughter as an apprentice.Footnote 49 Thus, while it seems likely that the payments from the charity land promoted human capital formation through pauper apprenticeships,Footnote 50 the fund clearly constituted a hidden supplement to the formal poor-law system, since most pauper children were being apprenticed outside the parish (as, for example, when the son of Grace Glover, widow, was taken on as apprenticeship by John Sulor of Silton (Dors.), linen weaver, who received £3 from the charitable trust funds).Footnote 51 Unsurprisingly, the medical costs were significant for the sick, the wounded, and persons with a disability. For example, the costs for taking Charles Rake to Bath to be cured of his malady was £1, while £3 was laid out to William Hill and William Webb to help three of their children to be cured in London. In 1679, William Baron, gent., received £1. 10s. ‘for curing of several poore people of the parish’.Footnote 52 On the other hand, loans accounted for 32 per cent (1660s) and 47 per cent (1670s) of the total value. The number of loans was 153; the number of people who received two loans was 16 and those who received three loans was four (one of them a widow). The highest loan was £20 for assistance following a house fire. The most common loan was for £3 with 100 examples (approximately 65% of the total), followed by 26 loans of £1 (approximately 17% of the total). However, 105 loans (about 69%) were not repaid and only 33 loans (about 22%) were repaid in full. This may have given rise to the discontinuation of loans and the switch to allowances.Footnote 53 In any case, credit and small debt must have been crucial to poor labourers, whose income and employment were irregular and uncertain. The shift from loans to allowances equivalent to the periodic forgiveness of small debts also might have constituted a hidden supplement to the formal poor-law system.Footnote 54

Figure 1. Average annual number of recipients and average annual income of forest money, Mere (Wilts).

Source: Wiltshire and Swindon History Center, 865/613, Account book of Gillingham (Dorset) forest charity: payments to the poor and sick of Source: Mere out of the revenue from 80 ac. Land late part of the forest with two 19th memoranda of the term of charity, 1657–1739; Endowed Charities (County of Wilts.), Parish of Mere, including the parish, formerly the tything of Zeals, London, 1907, p. 3.

Figure 2. Disbursement per 10 years for different types of relief.

Source: Wiltshire and Swindon History Center, 865/613, Account book of Gillingham (Dorset) forest charity: payments to the poor and sick of Source: Mere out of the revenue from 80 ac. Land late part of the forest with two 19th memoranda of the term of charity, 1657–1739.

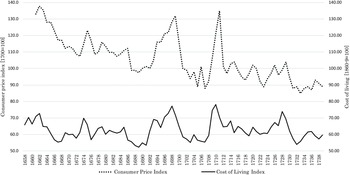

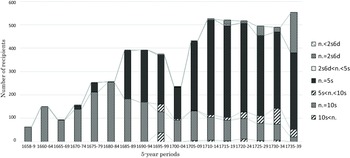

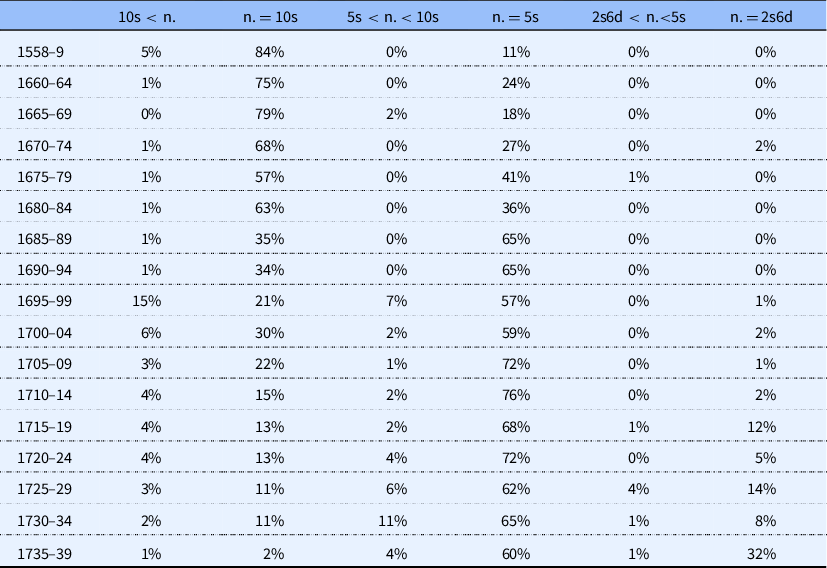

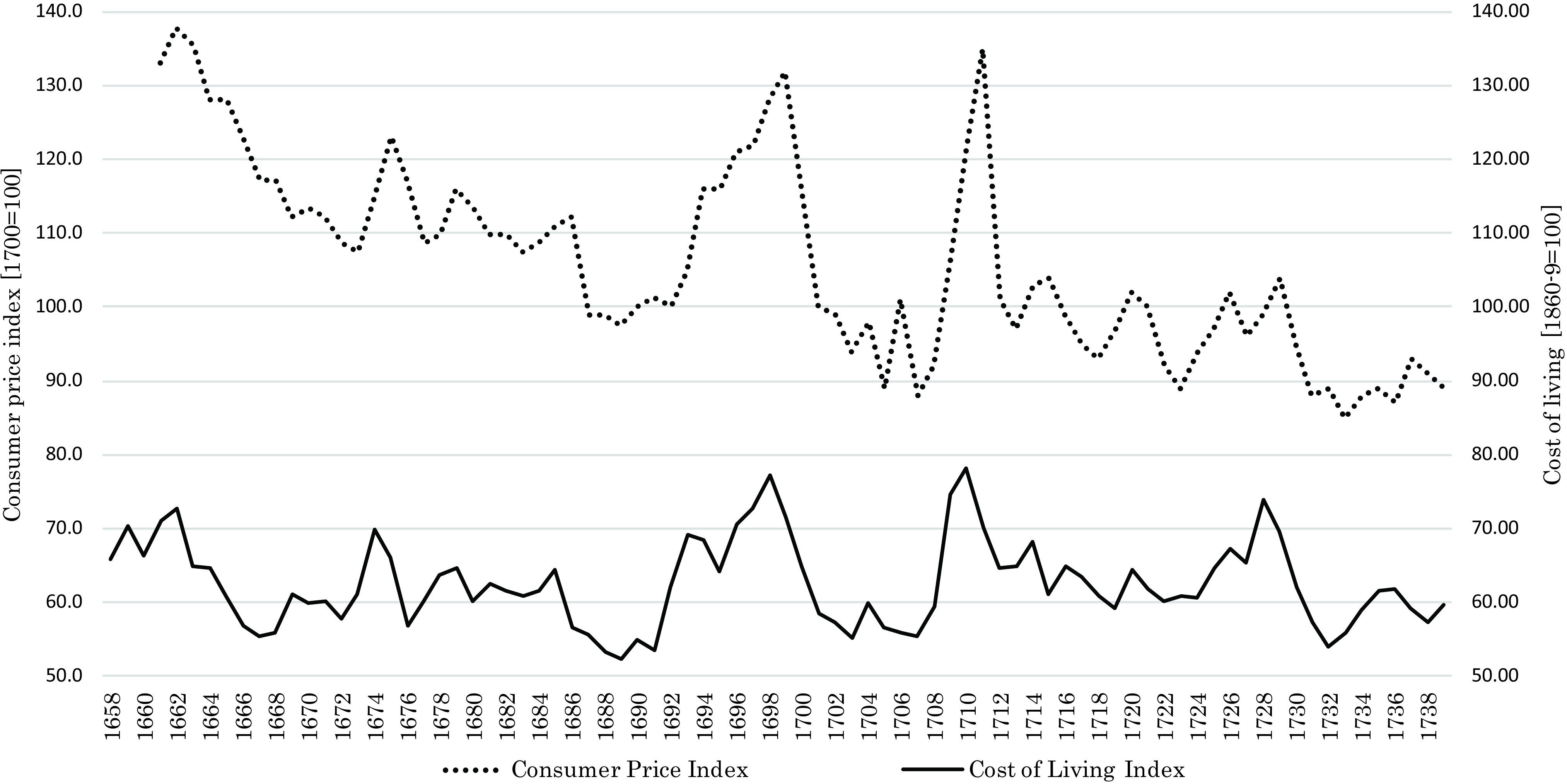

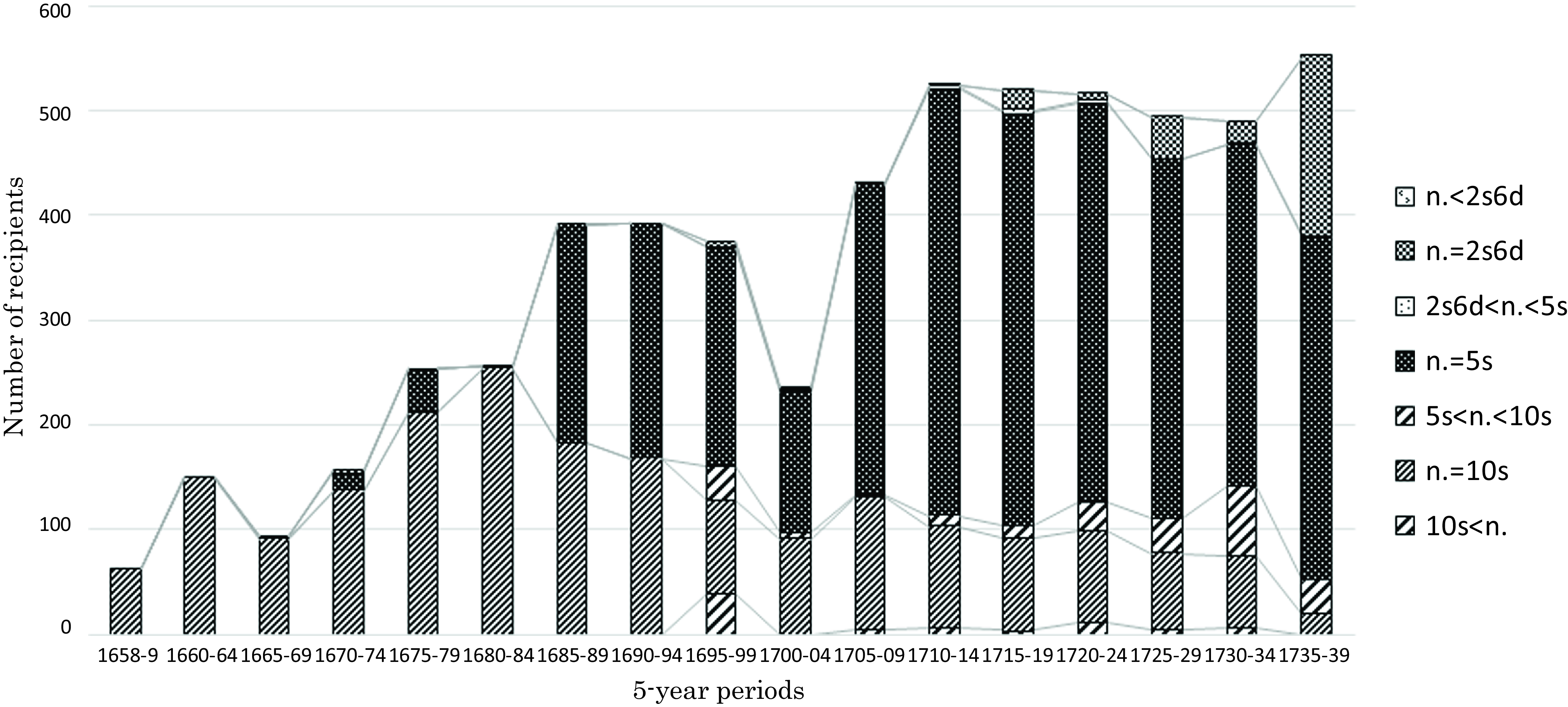

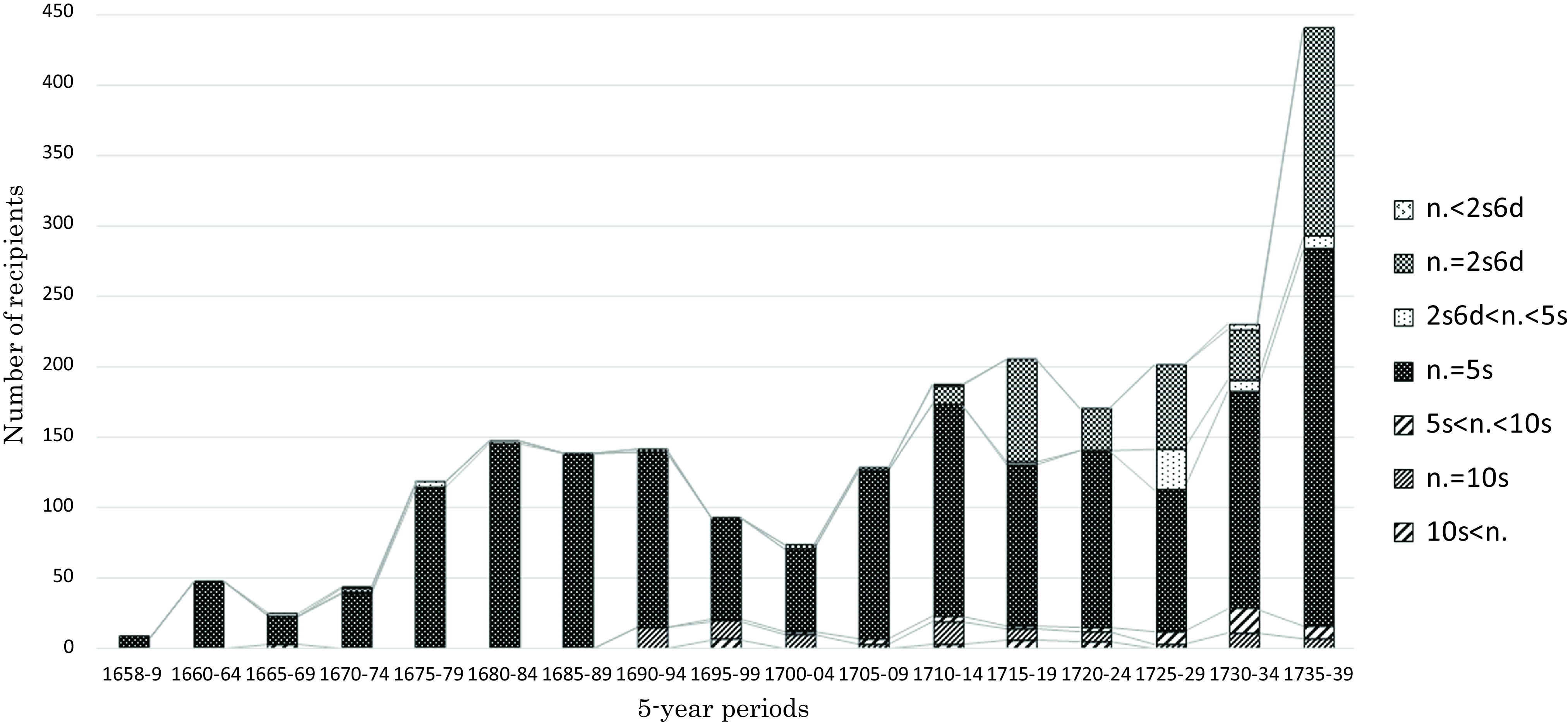

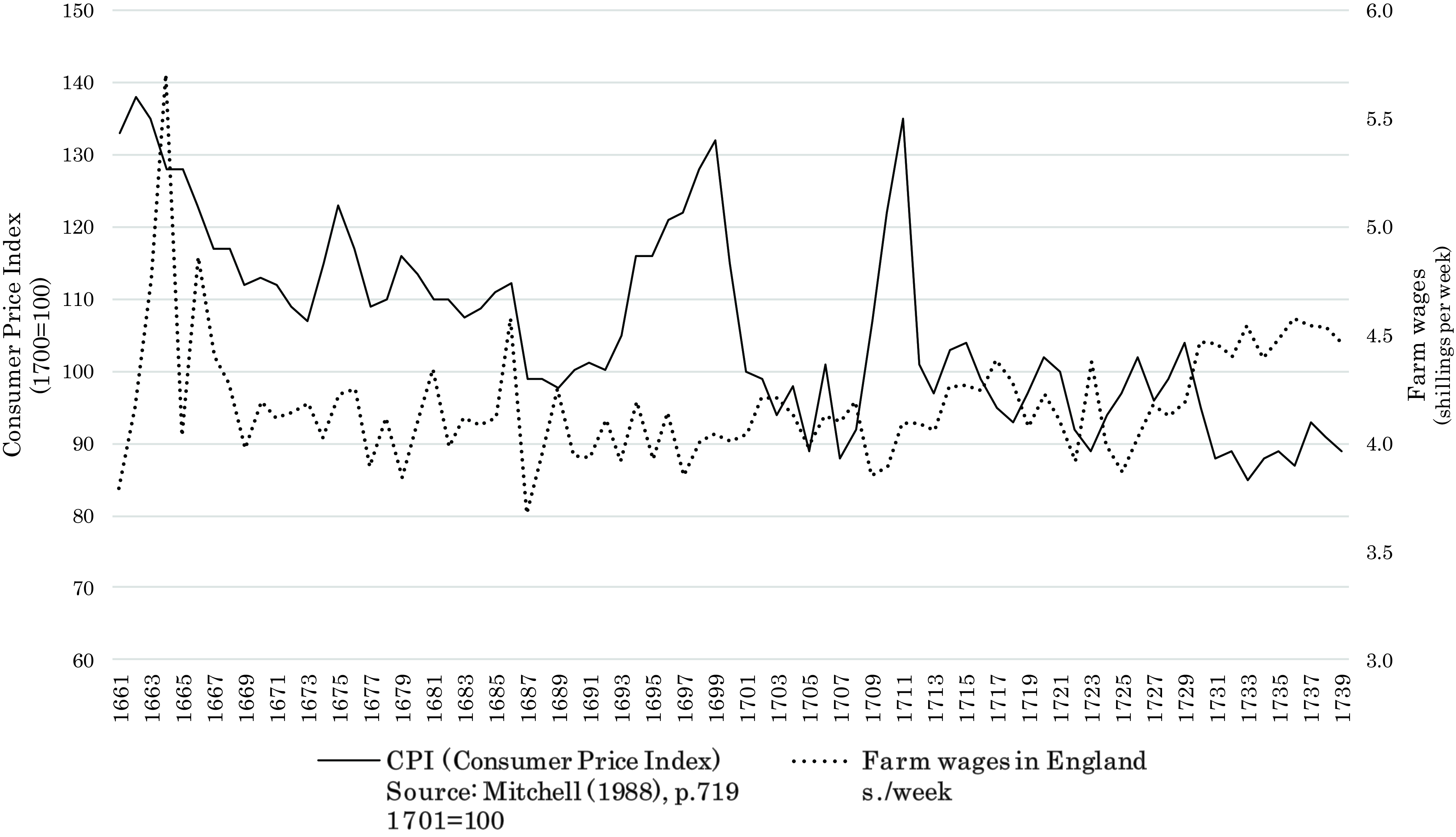

Table 3 illustrates the shifts over time in the distribution of the value of expenditure between various payments in each five-year period, according to how much relief they received per year. We find that the consumer price index declined towards c. 1690 (see Fig. 4) and that the proportion of 10 shilling payments plummeted from 63% (1680–84) to 35% (1685–89) and the proportion of 5 shilling payments increased from 36% to 65% over the same period (see Table 3). We also find that there was a rise in the consumer price index and cost of living around 1710 (see Fig. 3), at the same time as the distribution of five shillings remained between 72% and 76%. On the other hand, as Table 3 shows, during the fall in the consumer price index from the 1730s onwards, the proportion of 2 shillings 6 pence per capita payments increased from 8% (1730–4) to 32% (1735–9).Footnote 55 This shows that, by taking advantage of this downward trend in prices, the trustees managed to reduce the proportion of payments equalling 10 shillings per person and increase that of five shillings per head. Regardless of price inflation, the proportion of 10 shilling payments continued to fall and that of two shillings six pence to increase, amounting to almost one-third by 1735/39 (when those of 5 shillings occupied 60 per cent and those of 10 shillings accounted for just two per cent). It seems likely that the right balance between the necessary trust invested in the trustees and their discretional calculation of payments depended on the provisioning of immediate bridging income as a replacement for absent earnings that was at least closer to the normal weekly income for poor families. If agricultural labourers worked an average of four days per week (which incorporates periods of underemployment) as was the case at Terling (Essex) in the late seventeenth century,Footnote 56 then one-off payments of 10 shillings deflated by the consumer price index (10s. is equal to 7.2s.∼7.8s., if deflated),Footnote 57 would be equivalent to 1.8 ∼1.95 weeks earnings between 1661 and 1664, and 2.7∼2.9 weeks earnings between 1735 and 1739 years (10s. is equal to 10.7s.∼11.5s., if deflated). The five shilling payment per head was also equivalent to 0.9∼0.97 weeks earnings in 1661–4 and to 1.3∼1.4 weeks earnings in 1735–9. In addition, one-off payments of two shillings six pence were equivalent to 0.45∼0.49 weeks of earnings in 1661–4 and to 0.67∼0.72 weeks of earnings in 1735–9.Footnote 58 Although payments available from the charity land generally amounted to annualised figures of 2s. 6d to 10 shillings per head, if they supplied missing weekly income at such a rate twice a year (March 25 and September 29) when they were most required, they may have been regarded as fairly ‘generous’ by the successful recipients. In Mere, at any rate, prior to 1725, one-off payments (ten shillings and five shillings), equivalent to almost the adult male weekly wage or almost twice that amount respectively, were made to more than 80 per cent of recipients. This suggests that these sums (mainly in 2s. 6d, 5s. and 10s. doles) functioned either as short-term replacement income, when earning power was weakened by illness, accident, or unemployment, or supported an employment strategy through apprenticeships, financing loans or the purchase of working tools. If any of the payments went to the elderly, or to women, then the value of 2s. 6d may have been proportionately greater, because their earning capacity was lower than that of healthy adult men.

Table 3. Distribution of payments for the poor, Mere 1658–1739

Source: Wiltshire and Swindon History Center, 865/613, Account book of Gillingham (Dorset) forest charity: payments to the poor and sick of Mere out of the revenue from 80 ac. Land late part of the forest with two 19th memoranda of the term of charity, 1657–1739.

Figure 3. Consumer price index & Cost of living index.

Source: G. Clark, ‘The long march of history: Farm wages, population, and economic growth, England 1209–1869’, EcHR 60 (1) (2006), 97–135; B.R. Mitchell, British Historical Statics (Cambridge, 1998), p.719; R.C. Allen, ‘Prices and wages in London and southern England, 1259–1914’, http://163.1.40.People/sites/Allen/SitePages/Biography.aspx, on 29 October 2013.

Dynamics of poor relief

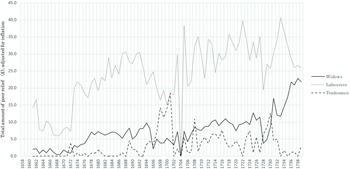

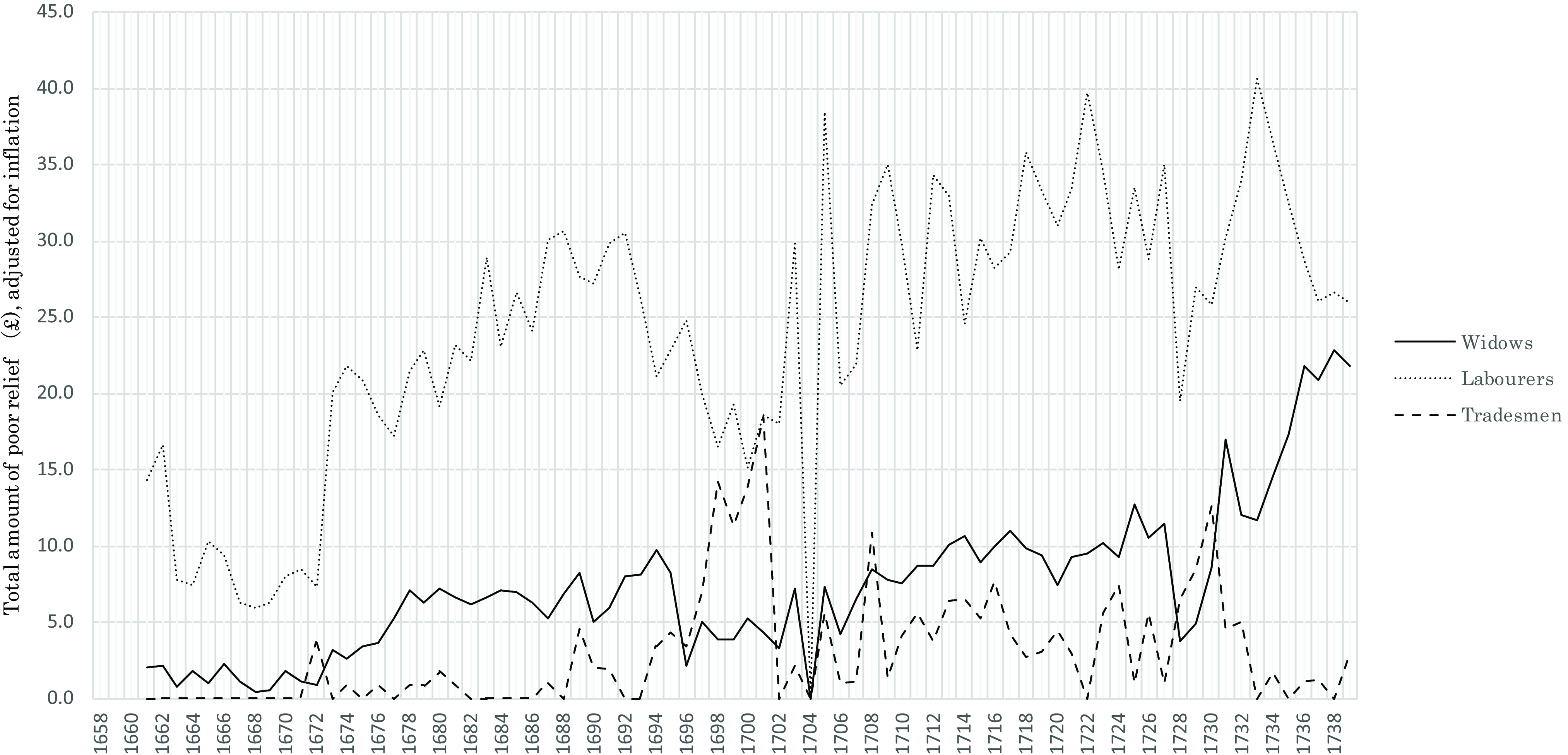

Figure 4 illustrates the total amounts of relief paid biannually to widows, labourers, and tradesmen between 1661 and 1739, corrected for inflation. These three types of recipients, initially categorised by their per capita receipt (£1 for tradesman, 10 shillings for labourers and 5 shillings for widows in 1658),Footnote 59 gradually changed into two categories – widows and male recipients – after 1680. Note that the recipients who received £1 or more are counted as tradesmen and male recipients who received 10 shillings or less are deemed to have been male labourers. The per capita receipts were rarely more than 10 shillings besides loans, medical care, apprenticeship, administrative expenses, or household equipment. Also, for simplicity of recording, payments to unmarried women have been counted as being to widows. In addition, unless positive evidence exists to show two individuals are the same person, the analysis has kept them separate. Figure 4 shows that the sums paid to labourers and widows had similar trajectories, but payments made to tradesmen were always subject to greater variation, because they encompassed relatively large one-off payments per head. The most surprising finding is a complete reversal in the pattern of expenditure. Until 1733, the payments to widows tended to follow those to male labourers, but after 1734 the payments to widows increased and those to male labourers declined, so that the disparity between them had greatly diminished by 1739. On the other hand, as Figure 5 shows, the number of widows receiving allowances tended to lag behind that of male labourers across the period. This is because, as Figure 5 shows, the trustees had inevitably to reduce the payments made to each category of recipients, according to their requests and necessities, in the economic situation surrounding them, since the total income (corrected for inflation) available from the charity land retained almost constant or increased only very slowly across the period. In other words, the trustees were caught on the horns of limited funds and a growing number of applicants for charitable funds. Trustees decided by their consensus how much the poor should receive according to their necessities.Footnote 60

Figure 4. Mere, 1661-1739: total amount of poor relief to widows, labourers and tradesmen.

Source: Wiltshire and Swindon History Center, 865/613, Account book of Gillingham (Dorset) forest charity: payments to the poor and sick of Mere out of the revenue from 80 ac. Land late part of the forest with two 19th memoranda of the term of charity, 1657–1739; B.R. Mitchell, British Historical Statics (Cambridge, 1998).

Figure 5. Number of recipients and the amount of income available from the poor land.

Source: Wiltshire and Swindon History Center, 865/613, Account book of Gillingham (Dorset) forest charity: payments to the poor and sick of Mere out of the revenue from 80 ac. Land late part of the forest with two 19th memoranda of the term of charity, 1657–1739.

Figures 6 and 7 illustrate how the trustees responded within their limited means to the growing number of people who wanted to receive one-off payments. The trustees changed the amount received as the number of recipients increased. For instance, in the case of the payments made to widows, it can be seen that after 1735 the trustees reduced the number of recipients who received allowances of 5s. and increased the eligibility for payments of 2s. 6d. Similarly, Figure 8 shows that in the years 1689–99 and 1717–11, prices jumped respectively by almost 35 per cent and 55 per cent, and the nominal wage level did not change significantly, so real income declined.Footnote 61 In sum, Figures 6 and 7 show that dependence increased with the timing of these rapid price increases. As Figure 5 shows, while the proportion of payments made to labourers rose to a peak in 1733 (77 per cent), and then fell back towards 1739 (51 per cent), a much greater proportion of payments (from 35 per cent of annual value of allowances in 1735 to 46 per cent in 1738) was devoted to widows. It seems likely that since the real value of payments to poor labourers had become more valuable, the trustees reduced them, as the number of actual applicants rose, and then shifted their priorities towards widows. The actual amounts received by poor labourers on each occasion were substantial, chiefly 5s. and 10s. before the early 1730s, but in the late 1730s payments per head were diminished, with most applicants receiving 5s. and 2s. 6d., while unsurprisingly the number of widows in receipt of payments and the amounts they received both substantially increased.

Figure 6. Mere, forest money: distribution of payments for labouring poor.

Source: Wiltshire and Swindon History Center, 865/613, Account book of Gillingham (Dorset) forest charity: payments to the poor and sick of Mere out of the revenue from 80 ac. Land late part of the forest with two 19th memoranda of the term of charity, 1657–1739.

Figure 7. Mere, forest money: distribution of payments for widows.

Source: Wiltshire and Swindon History Center, 865/613, Account book of Gillingham (Dorset) forest charity: payments to the poor and sick of Mere out of the revenue from 80 ac. Land late part of the forest with two 19th memoranda of the term of charity, 1657–1739.

Figure 8. Consumer price index and farm wages (1661–1739).

Source: G. Clark, ‘The long march of history: farm wages, population, and economic growth, England 1209-1869’, EcHR 60 (1) (2006), 97–135; Mitchell, British Historical Statics, p.719; Allen, ‘Prices and wages’.

Why was it necessary to prioritise the welfare of widows to the detriment of labouring men who were household heads? The fact that small and intact families enjoyed high and rising living standards after 1700, as Horrell, Humphries, and Weisdorf suggest, while disrupted families – families whose husbands/fathers were unable to work at the intensity assumed, and families whose husbands/fathers had died or disappeared – had recourse to alms or poor relief, probably explains this coping strategy.Footnote 62 On the other hand, from 1724 onwards, the previous references to ‘widdowe’ in the account book noticeably change to ‘widdow &c’ or ‘women’. In addition, the Forest Charity’s account book lists a flax-dresser – William Coward, a man in a skilled trade – as a poor labourer in 1724 and afterwards. In general, flax dressers – ‘dressing’ being the process involving in turning a flax into fibre that could be spun – also engaged in flax-dealing and worked in central workshops in towns, near to the source of raw materials. Coward received five shillings in 1728 and received further cash payments from the charity on 14 occasions between 1732 and 1739.Footnote 63 It is possible that the shift during the 1730s in the proportion of payments awarded to female recipients might have been affected by the growing impoverishment of flaxdressers, since some of them probably drew and twisted the fibres into continuous yarn by using a spinning wheel. In other words, many women including spinsters might have been excluded from the high-wage economy, endorsing the findings of Humphries and Schneider: the evolution of spinners’ wages identified as an apparent boom circa 1710, but returning to more traditional levels thereafter, should not be regarded as the inevitable participation in a high-wage economy.Footnote 64 On the other hand, this shift in payments from men to women may also have made the value of benefits greater for the latter, because their earning capacity was lower than that of healthy adult men, so that many benefited indirectly from the high-wage economy.

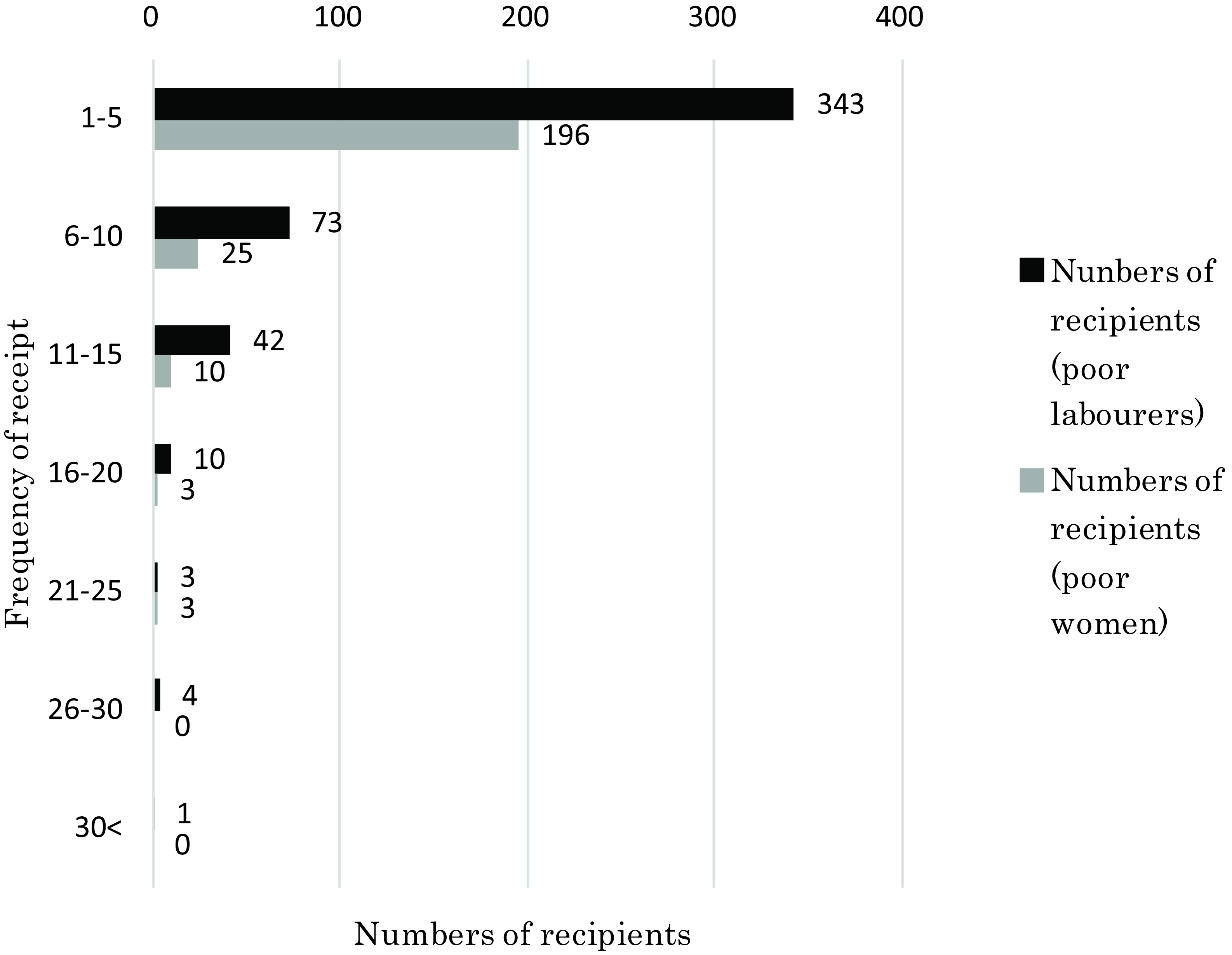

Lastly, as Figure 9 illustrates, in relation to the frequency of per capita receipts for recipients, the highest frequency was one to five times both for poor labourers (72%) and widows (83%), suggesting some resilience among the poor who did not receive rate-based parochial relief. The funds available from the charity land could function as stop-gap payments, in a system that was designed to deal with such emergencies as illness,Footnote 65 accident,Footnote 66 or unemployment, or as lump-sum ‘enabling’ payments for the purpose of repairing or building a shop etc.Footnote 67 or acquiring working tools (including looms, some of which might cost in excess of £1).Footnote 68 In this sense, it might be that the charity land served as a safety net for those who lacked alternatives to formal relief, or in other words offered ‘new commons for the poor’.Footnote 69 This operation of the ‘economy of makeshifts’ – although Hufton defined this not as charity and formal poor relief but as more expansive and diversified welfare which encompassed the strategies of the poor in ‘making do’ –Footnote 70 was resilient in response to different life-cycle stages or different causes and durations of poverty that the ‘second’ poor faced. All this was possible because the trustees who managed, controlled, and executed charitable trusts had a keen appreciation of the value of the economy of makeshifts. But it depended on the trustees who determined the amounts of payments according to applicants’ necessities on the basis of ‘a list of the names of so many poor people as wanted relief that the clerk made.Footnote 71 In this respect, the operation of the system calls into question the explicit and implicit sense in much of the historiography on welfare that the poor were able to cross over into the mixed economy of welfare with relative ease.Footnote 72 The ‘second poor’, who could not receive the rate-based parochial relief, themselves clearly perceived the advantage of a charitable trust as part of economy of makeshifts. This might suggest that there was a difference between the culture of poverty, sustaining a cycle of poverty across generations, and the culture of makeshifts; a contrast between the ‘first poor’ who were caught in grinding whole-life poverty, and the ‘second poor’ who only experienced the odd incident.Footnote 73

Figure 9. Frequency of receipt for Recipients (1651-1739).

Source: Wiltshire and Swindon History Center, 865/613, Account book of Gillingham (Dorset) forest charity: payments to the poor and sick of Mere out of the revenue from 80 ac. Land late part of the forest with two 19th memoranda of the term of charity, 1657–1739.

Conclusion

This paper has analysed the distribution practice for poor relief derived from an account book (1658–1739) of the charity land allotted after the disafforestation of Gillingham Forest. It has explored how payments shifted over the period, and how the spectrum of relief adjusted to massive macro-level changes – specifically poor labourers’ improving standard of living that occurred between c.1660 and c.1760. Since this charity continued to function into at least the twentieth-century, resembling, as section 1 suggests, the median value per capita of other charity land observed throughout the dataset derived from the Brougham Commission, it might be that these findings from a detailed consideration of a single parish are more widely applicable, although particular features may be associated with the way that poor relief from the charity land was closely knit into the fabric of the local economy of linen cloth production.

Unlike the rate-based parochial casual payments, which primarily consisted, in descending order of significance, of medical care, fuel provision, rent payments, fuel, and clothing, as the third section illustrates, one-off payments available from the charity land primarily consisted of cash payments of 10 shillings, 5 shillings or 2 shillings 6 pence. When deflated by the consumer price index, these payments were equivalent to about 1–3 weeks earnings, and their relative proportions were strongly influenced by the upward and downward movements in prices. This confirms the intimate connections between distribution practices for poor relief and occupational structures, in this case those within which underemployed weavers and spinners worked.

As section 4 illustrates, since the real wages of labourers and wage earners were improving across the period, the payments to male recipients per capita gradually declined from five shillings per capita to two shillings six pence per head, while fluctuating in terms of numbers. After the mid-1730s, however, the emphasis of poor relief was placed on widows and poor women, while reducing the payments to married labouring men, because disrupted families – families whose husbands/fathers were unable to work at the intensity assumed and families whose husbands/fathers had died or disappeared – had recourse to alms or poor relief, irrespective of growing standards of living. In this respect, it seems likely that many women including spinsters might have been, in fact, excluded from the high-wage economy, despite the fact that spinning as well as weaving under the putting-out system played a crucial role in an economy of makeshifts in this region where proto-industry was well established.

By analysing the size of payments to the poor who did not receive rate-based parochial relief, the fact that the trustees provided them with allowances equivalent to immediate bridging income to fill the temporary gaps in income at a realistic level, while clarifying the role-sharing between charitable funds and rate-based casual poor relief, also suggests that the trustees regarded the recipients as a part of a reserve labour force and positioned this poor relief system for employment promotion or unemployment relief. The parish had an interest in relieving the second poor who did not receive rate-based parochial relief, in view of the need to deal with the precarious and uncertain nature of seasonal employment, but the trustees took advantage of the well-developed institutionalised charity, and funds derived from the post-disafforested charity land, rather than financing it through formal relief. This study illustrates that a relatively large share of the population of Mere was compelled to live at low-income levels during the period 1650–1750, a time when the standards of living among wage earners generally improved significantly.

In conclusion, this paper has demonstrated how the charity operated within the local economy as part of the economy of makeshifts, how it was integrated into systems of domestic textile production, and how parish authorities were able to balance the different financial resources available both from formal relief and parish charities. They were able to direct these charitable funds to help different groups, particularly the elderly and women, because their earnings were usually much lower than those of healthy adult men. This indicates not only the direct exclusion of women from the high-wage economy but also the way they benefited from it indirectly. It further shows that the local authority managed to cope with increasing economic polarisation in rural society by providing the poor, who could not receive rate-based parochial relief, with the doles available from the charity land, indicating that the public-private collaboration or partnership had continued across the centuries. The two resources frequently interacted or overlapped in relieving the poor. With a detailed analysis of this size, the observed changes in relief practices provide a powerful insight into the nature and importance of the role such institutionalised charities played in the lives of those who could not – or would not – receive rate-based parochial relief.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Henry French and Alannah Tomkins for their constructive feedback on my research and insightful comments on this article. Also, I would like to thank Brodie Waddell and Jonathan Healey for reading and commenting on earlier drafts, and finally, Tom Williamson, Editor of Rural History for his support, and anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.