Introduction

Global mean temperatures are likely to rise by 0.4 to 1.6°C by 2046–2065 and 2.6 to 4.8°C by 2081–2100, depending on the greenhouse gas emissions scenarios considered, with the potential to reduce crop production (without adaptation), whilst the effect of climate change on future rainfall patterns is less certain, but increased variability is likely (IPCC, 2014). Such projections imply negative impacts on crop production in rice (Oryza sativa L.) (Wassmann et al., Reference Wassmann, Jagadish, Heuer, Ismail, Redonã, Serraj, Singh, Howell, Pathak and Sumfleth2009; Teixeira et al., Reference Teixeira, Fischer, Velthuzein, Walter and Ewert2013; Zainal et al., Reference Zainal, Shamsudin, Mohamed, Adam and Kaffashi2014). In addition to the tendency for lower seed yield from shorter crop durations, due to more rapid progress to maturity at warmer temperatures, brief exposure to high temperature around anthesis can reduce spikelet fertility in rice and hence yield (Yoshida, Reference Yoshida1981; Jagadish et al., Reference Jagadish, Craufurd and Wheeler2008).

Rice production is constrained by water shortage (Arora, Reference Arora2006; Tao et al., Reference Tao, Brueck, Dittert, Kreye, Lin and Sattelmacher2006). Less water is available for irrigation due to climate change and competition from urbanization and industrial development (Pennisi, Reference Pennisi2008) and over half of the global rice production area, much of it rainfed (Murty and Kondo, Reference Murty and Kondo2001; Kamoshita et al., Reference Kamoshita, Babu, Manikanda Boopathi and Fukai2008), is affected by drought (Bouman et al., Reference Bouman, Peng, Castañeda and Visperas2005). Drought stress occurs after a prolonged period of water shortage leading to permanent wilting and ultimately death (O'Toole, Reference O'Toole1982). In rice the effect of drought varies with variety, degree and duration of stress and the timing of when it occurs during development (Zeigler and Puckridge, Reference Zeigler and Puckridge1995; Kato et al., Reference Kato, Abe, Kamoshita and Yamagishi2006). Water shortage is often unpredictable, not occurring in all years in a given location, and thus affects the stability of production and quality, and hence resilience.

Rice production is dependent upon the availability of high-quality seed, the production of which is also affected by environment. Seed quality (seed longevity and desiccation tolerance) in Japonica rice was reduced considerably when produced under warmer (34/26°C) rather than cooler (28/20°C) temperatures (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Hong and Jackson1993; Ellis and Hong, Reference Ellis and Hong1994). Similarly, brief exposure to 34 or 38°C for 7–14 days after anthesis reduced the subsequent viability of rice seeds at harvest maturity (Martínez-Eixarch and Ellis, Reference Martínez-Eixarch and Ellis2015), whilst in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) short exposure to high temperature (34/20°C) 7–14 days after anthesis reduced the subsequent longevity of seeds at harvest maturity (Nasehzadeh and Ellis, Reference Nasehzadeh and Ellis2017).

Drought during the seed-filling phase damages rice seeds, primarily by inducing earlier senescence and reducing the grain-filling period and seed yield (Yeo et al., Reference Yeo, Cuartero, Flowers and Yeo1996; Bouman and Tuong, Reference Bouman and Tuong2001; Sikuku et al., Reference Sikuku, Netondo, Onyango and Musyimi2010). The effect on seed quality is less well understood. Generally, drought stress during seed development is said to reduce crop seed quality (Barnabas et al., Reference Barnabas, Jager and Feher2008; Stagnari et al., Reference Stagnari, Galieni, Pisante and Ahmad2016). Ending irrigation early at 16 or 24 days after pollination brought forward the subsequent temporal pattern of improvement, and later decline, of seed quality in planta in Brassica campestris [rapa] L. (Sinniah et al., Reference Sinniah, Ellis and John1998a). Nonetheless, the maximum longevity of seeds from plants subjected to terminal drought was slightly greater than for control plants irrigated throughout. Crop water stress had no significant effect on seed quality in pea (Pisum sativum L.) (Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, Warrington and Scott1978) or pinto bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) (Ghassemi-Golezani et al., Reference Ghassemi-Golezani, Chadordooz-Jeddi, Nasrollahzadeh and Moghaddam2010), whereas water deficit during seed filling reduced ability to germinate in dill (Anethum graveolens L.) (Zehtab-Salmasi et al., Reference Zehtab-Salmasi, Ghassemi-Golezani and Moghbeli2006), soya bean (Glycine max L.) (Ghassemi-Golezani et al., Reference Ghassemi-Golezani, Lotfi and Norouzi2012), and wheat (Tarawneh et al., Reference Tarawneh, Szira, Monostori, Behrens, Alqudah, Thumm, Lohwasser, Röder, Börner and Nagel2019). In contrast, Vieira et al. (Reference Vieira, Tekrony and Egli1991) reported that ability to germinate in soya bean was not affected by drought during seed filling.

We tested the null hypotheses that each of drought and brief exposure to high temperature applied at different times during seed development do not affect rice seeds’ subsequent ability to germinate and their longevity in air-dry storage. The environment of seed production may affect the temporal pattern of seed quality development and decline (Ellis, Reference Ellis2019) and so its response to drought was investigated here. Drought and high temperature are good examples of different abiotic stresses that often occur simultaneously in the field (Moffat, Reference Moffat2002; Shah and Paulsen, Reference Shah and Paulsen2003) and whose effects can reinforce each other: transpiration through the stomata in warm regimes cools plants, but if high temperature and drought are combined then transpiration is limited and leaf temperature rises (Rizhsky et al., Reference Rizhsky, Liang and Mittler2002). Hence, the effects of drought and brief exposure to high temperature on rice seed quality were investigated separately and together.

Materials and methods

Experiments were conducted with cvs Gleva (Experiments 1–4) and Aeron 1 (Experiment 4). Gleva is a high-yielding early-maturing, Japonica cultivar grown in Spain. Seeds were provided by the Institute of Agrifood Research and Technology, Barcelona, Spain. Aeron 1 is a high-yielding, aerobic Indica rice with early harvest maturity grown in Malaysia (Zainudin et al., Reference Zainudin, Sariam, Chan, Azmi, Saad, Alias and Marzukhi2014). Seeds were provided by the Malaysia Agriculture Research Development Institute, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia.

Plants were grown in 180 mm diameter (3-litre) plastic pots (with drain holes). The growing media consisted of coarse sand, crushed gravel, peat compost and vermiculite in the ratio 2:4:1:4. Slow-release fertilizer (Osmocote Pro 3-4M, Everris International BV, The Netherlands) containing N:P2O5:K2O:MgO (17:11:10:2) was added at 3 kg m‒3. The pots with media were pre-soaked with tap water and then left to drain overnight. Seven seeds were sown 15 mm deep in each pot and seedlings thinned to four per pot 14 days after sowing (DAS). Pots were irrigated (water without nutrient, adjusted to pH 4.5–5.5) by hand from 3 until 16 DAS and then by automatic drip irrigation seven times each day until 42 DAS, then three times each day. Savona (Koppert B.V., The Netherlands) with 10 ml l–1 fatty acids was used occasionally to control red spider mites and aphids when detected.

Experiment 1

The first experiment investigated the effect of drought on seed quality development in cv. Gleva. Seeds were sown on 25 November 2014 and the experiment was carried out in a modified Saxcil controlled-environment growth cabinet (internal dimensions 1.4 × 1.4 × 1.5 m) at the Plant Environment Laboratory (PEL), University of Reading (51° 24′ N, and 00° 56′ W). Cool white fluorescent tubes provided an average 720 μmol m–2 s–1 photosynthetic photon flux density at pot level. The temperature regime was 28/20°C day/night (11 h/13 h thermoperiod, synchronized with 11 h day–1 photoperiod) at 75% relative humidity. Three irrigation treatments were applied: plants irrigated throughout the experiment [i.e. until 40 days after 50% anthesis (DAA)], the control (T1); irrigation ended 7 DAA (T2); or ended 14 DAA (T3). Only panicles that anthesed between 101 and 108 DAS were included in the study (other panicles were cut and removed). Anthesis (0 DAA) was 105 DAS (i.e. 50% anthesis). Serial harvests of plants began at 7 DAA and continued at 4–6 days intervals on eight occasions until 40 DAA. Eight plants (two pots) were harvested from each irrigation treatment on each date and seeds threshed. The 24 treatment combinations were assigned to the 48 pots at random at panicle exsertion.

Experiment 2

This experiment, sown on 21 May 2016 in a controlled-environment (photoperiod controlled, heated and vented) glasshouse at the Crop Environment Laboratory (CEL), Whiteknights, University of Reading (51° 26′ N, 0° 56′ W), investigated the effect of drought (later in seed development than Experiment 1) on seed quality development in cv. Gleva. Pots were placed on one of four trolleys (each 2.2 × 1.4 m, with 63 pots comprising one block). The glasshouse was controlled at 28/20°C (12 h/12 h thermoperiod, synchronized with a 12 h day–1 photoperiod). Relative humidity was maintained at about 70–80% by watering the floor of the glasshouse regularly. Plants in the control treatment (T1) were irrigated throughout (i.e. until 55 DAA). Irrigation ended 14 (T2) or 28 DAA (T3) in the drought treatments (i.e. late seed filling and mid-maturation drying, respectively). The positions of the pots representing each treatment combination were randomized within each trolley. Plants reached 50% anthesis (0 DAA) at 76 DAS. Only seeds from panicles that anthesed between 70 and 81 DAS were included in the study. A total of seven serial harvests of the developing and maturing seeds were taken from 13 to 55 DAA (i.e. a later final harvest than Experiment 1) at 6–8 day intervals. Twelve plants (three pots) were harvested from each block for each irrigation treatment on each date.

Experiment 3

The effect of brief exposure to high temperature at different stages during seed development and maturation on subsequent seed quality at harvest maturity was investigated in cv. Gleva in a controlled-environment (photoperiod controlled, heated and vented) glasshouse (6.4 × 8.6 m) and a modified Saxcil growth cabinet at PEL. Seeds were sown on 11 April 2015 in a glasshouse maintained at 28/20°C day/night (12 h/12 h thermoperiod, synchronized with 12 h day–1 photoperiod). The treatments consisted of a control (no high temperature treatment; T1), or different 3-day periods in the growth cabinet at 40/30°C (11 h/13 h thermoperiod synchronized with 11 h day–1 photoperiod) from –3 to 0 DAA (T2), 0 to 3 DAA (T3), 3 to 6 DAA (T4), 6 to 9 DAA (T5), 9 to 12 DAA (T6), 12 to 15 DAA (T7), 15 to 18 DAA (T8), 18 to 21 DAA (T9), 21 to 24 DAA (T10), or 24 to 27 DAA (T11). Plants were returned to the glasshouse after high-temperature treatment. Each treatment was represented by five pots of plants in each of four blocks (four trolleys each 3.5 × 2.1 m). Plants reached 50% anthesis (0 DAA) at 85 DAS (i.e. 50% anthesis) and panicles that anthesed outside the period 81–87 DAS were excluded from the study (cut and removed). Irrigation of all treatments continued throughout the investigation. Panicles were harvested at harvest maturity on 11 August 2015 (42 DAA).

Experiment 4

The effects of drought and/or a brief high temperature episode on seed quality at harvest maturity in cvs Aeron 1 and Gleva were investigated in modified Saxcil controlled-environment growth cabinets at CEL. The seeds were sown on 17 September 2016. Each of two cabinets (intended to provide two blocks) was maintained at 28/20°C (11 h/13 h thermoperiod synchronized with 11 h photoperiod) with 24 pots of each cultivar. Each cultivar was grown on separate sides of each cabinet, because their plant stature and development varied considerably, with treatments randomized within each cultivar. A third growth cabinet was maintained at 40/30°C (11 h/13 h thermoperiod, synchronized with an 11 h day–1 photoperiod) to provide high temperature (HT). Plants subjected to HT were transferred to this cabinet for 3 days, either in early seed development (0–3 DAA) or late in seed filling (14 DAA), and then returned to 28/20°C. Six treatments were applied to plants of each cultivar: a control at 28/20°C and irrigated throughout (i.e. until 35 DAA); HT at 0–3 DAA and irrigated throughout; irrigation ended at 14 DAA; HT at 0–3 DAA combined with irrigation ended at 14 DAA; HT at 14–17 DAA combined with irrigation ended at 14 DAA; HT at 14 DAA and irrigated throughout. Each cultivar was represented by eight pots in each treatment combination (four in each cabinet at 28/20°C). The date of anthesis varied amongst cultivars, but also between cabinets for cv. Gleva. Cultivar Aeron 1 reached 50% anthesis at 90 DAS, whereas in cv. Gleva this was at 114 DAS in cabinet 1 but 8 days later (122 DAS) in cabinet 2. In cultivar Aeron 1, only panicles that anthesed between 88 and 95 DAS were included in harvests, whilst in cv. Gleva these ranges were 110–118 DAS (cabinet 1) or 118–126 DAS (cabinet 2). Irrigation ended at 35 DAA, in both cultivars, for those treatments not subjected to terminal drought from 14 DAA. This was 7 days before panicles were harvested at 42 DAA (harvest maturity).

Seed assessment

Seeds were threshed gently from panicles from each harvest by hand and empty seeds removed. Mean seed dry weight was calculated from fresh weight and moisture content. Eight samples of 100 fresh seeds, selected at random, were counted and weighed to estimate mean seed fresh weight. Seed moisture content was estimated on the fresh weight basis using the high-constant-temperature-oven method with ground seed (ISTA, 2013). The two-stage method was applied for seed at high moisture contents (ISTA, 2013). Harvested seeds were dried at 15–17°C with 12–15% relative humidity to 10–14% moisture content (estimated by change in sample weight). Ability to germinate of these dried seeds was assessed on samples of 100 seeds (two replicates of 50) in moist rolled paper towels (Kimberly Clark Professional 6802 Hostess, Natural, 240 × 350 mm, Greenham Sales, UK) at 34/11°C (16 h/8 h) for 21 days (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Hong and Roberts1983). Seedlings were assessed for normal seedling development (ISTA, 2013). Seeds which remained firm after 21 days were pricked and the test extended to 28 days to break dormancy.

Seed longevity was assessed in hermetic storage in sealed laminated aluminum foil bags (Retort laminate, Moore and Buckle Ltd, St Helens, UK) at 40 ± 0.5°C with 15 ± 0.5% moisture content; 10–14 samples (depending upon seed available) of 100 seeds each for each treatment combination were stored for different periods. Seed moisture content was adjusted by placing weighed seed samples (in a muslin bag) over water at 20°C for 2–40 h, with change in seed weight monitored. Seed samples were then held together within separate muslin bags in a sealed container at 2–4°C for 3 days to allow moisture to equilibrate within and between samples. Moisture content was then determined as above. Samples were withdrawn from storage at regular intervals for up to 40 days and ability to germinate normally then assessed.

Seed survival curves were fitted by probit analysis in accordance with the equation:

$$v = K_{\rm i} - p/\sigma, $$

$$v = K_{\rm i} - p/\sigma, $$where v is probit percentage viability after p days in storage in a constant environment, K i is a constant specific to the seed lot (equivalent to initial probit viability), and σ is the standard deviation of the frequency distribution of seed deaths in time (days) (Ellis and Roberts, Reference Ellis and Roberts1980). The product of K i and σ is the period for viability to decline to 50% (p 50). The ability of a seed to produce a normal seedling was the criterion of survival. Genstat (17th edition, VSN International Ltd, UK) was used for all statistical analyses. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare seed weight, moisture content and ability to germinate amongst treatments in Experiments 3 and 4, where serial harvests were not possible, with means compared using Tukey's multiple range test (P = 0.05). Observations for ability to germinate were transformed to angles before ANOVA.

Results

Seed moisture content, weight, and ability to germinate

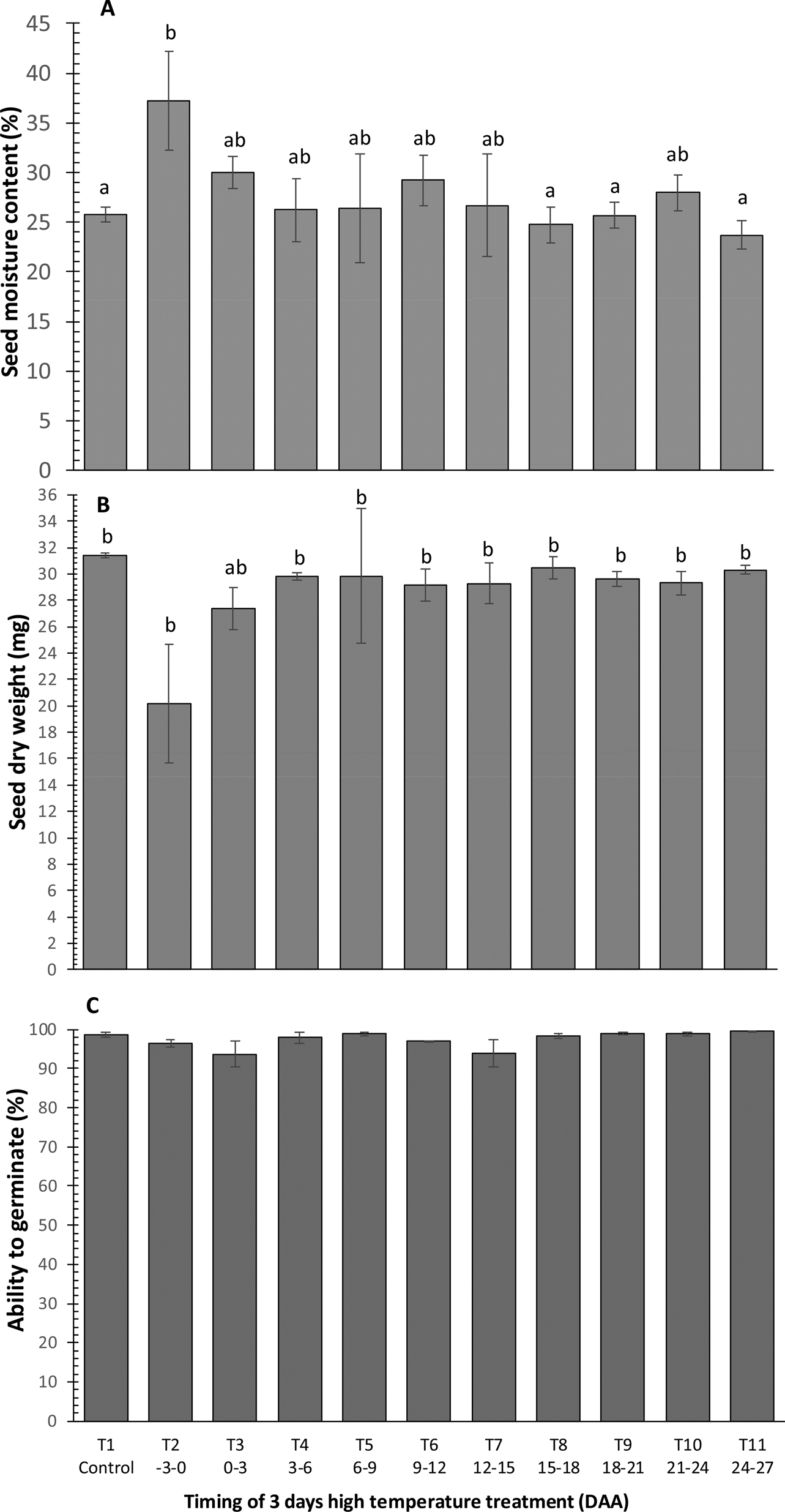

Seed moisture content in plants irrigated throughout declined from over 50% to below 30% between 7 and 40 DAA in Experiment 1, whereas ending irrigation at 7 or 14 DAA resulted in earlier and greater declines with both irrigation treatments in equilibrium with cabinet relative humidity at about 15% moisture content between 25 and 40 DAA (Fig. 1A). In Experiment 2, seed moisture content had already declined to less than 30% by the first harvest at 13 DAA subsequently stabilizing at ca 25% in the control between 34 and 55 DAA (Fig. 1B). Ending irrigation at 14 or 28 DAA led to rapid loss in moisture with seed from both irrigation treatments equilibrating at about 14% moisture content between 34 and 55 DAA.

Fig. 1. Changes in moisture content (A,B), dry weight (C,D) and ability to germinate normally after desiccation to 10–14% moisture content (E,F) of seeds of Japonica rice cv. Gleva harvested serially during their development and maturation from plants grown in a cabinet at 28/20°C (11 h/13 h) with 11 h day–1 photoperiod (Experiment 1: A,C,E) or in a glasshouse at 28/20°C (12 h/12 h) with 12 h day–1 photoperiod (Experiment 2: B,D,F). Plants were irrigated throughout ( ■ ), or until 7 (●), or 14 (▲), or 28 DAA (◆). Vertical bars represent means ± standard error of mean, where larger than symbols.

Seed filling continued until around the penultimate harvest at 35 DAA in Experiment 1 for the control, whereas it ended at around 10 or 20 DAA for plants where irrigation ended at 7 or 14 DAA, respectively; with lighter seed, the earlier irrigation ended (Fig. 1C). All three treatments in Experiment 2 showed similar dry weights throughout the study period with a mean seed weight of 27.3 mg at the final harvest (Fig. 1D). This value was also similar to the control, but considerably more than the plant drought treatments, in Experiment 1.

Ability to germinate after desiccation in Experiment 1 increased progressively during seed development in the control reaching close to 100% at 26 DAA, with this value maintained until the final harvest at 40 DAA (Fig. 1E). The increase occurred sooner after anthesis in the two drought treatments, but ability to germinate then declined progressively and considerably beyond 16 DAA where plant irrigation ended at 7 DAA, or 26 DAA (but a smaller decline) where irrigation ended 14 DAA. Ability to germinate after desiccation in Experiment 2 was already 78–86% by 13 DAA and increased to 100% in later harvests in all three irrigation treatments with no evidence whatsoever of a subsequent decline (Fig. 1F). The proportion of seeds remaining ungerminated after 21 days in test, i.e. still dormant and so pricked then, declined during seed development and maturation.

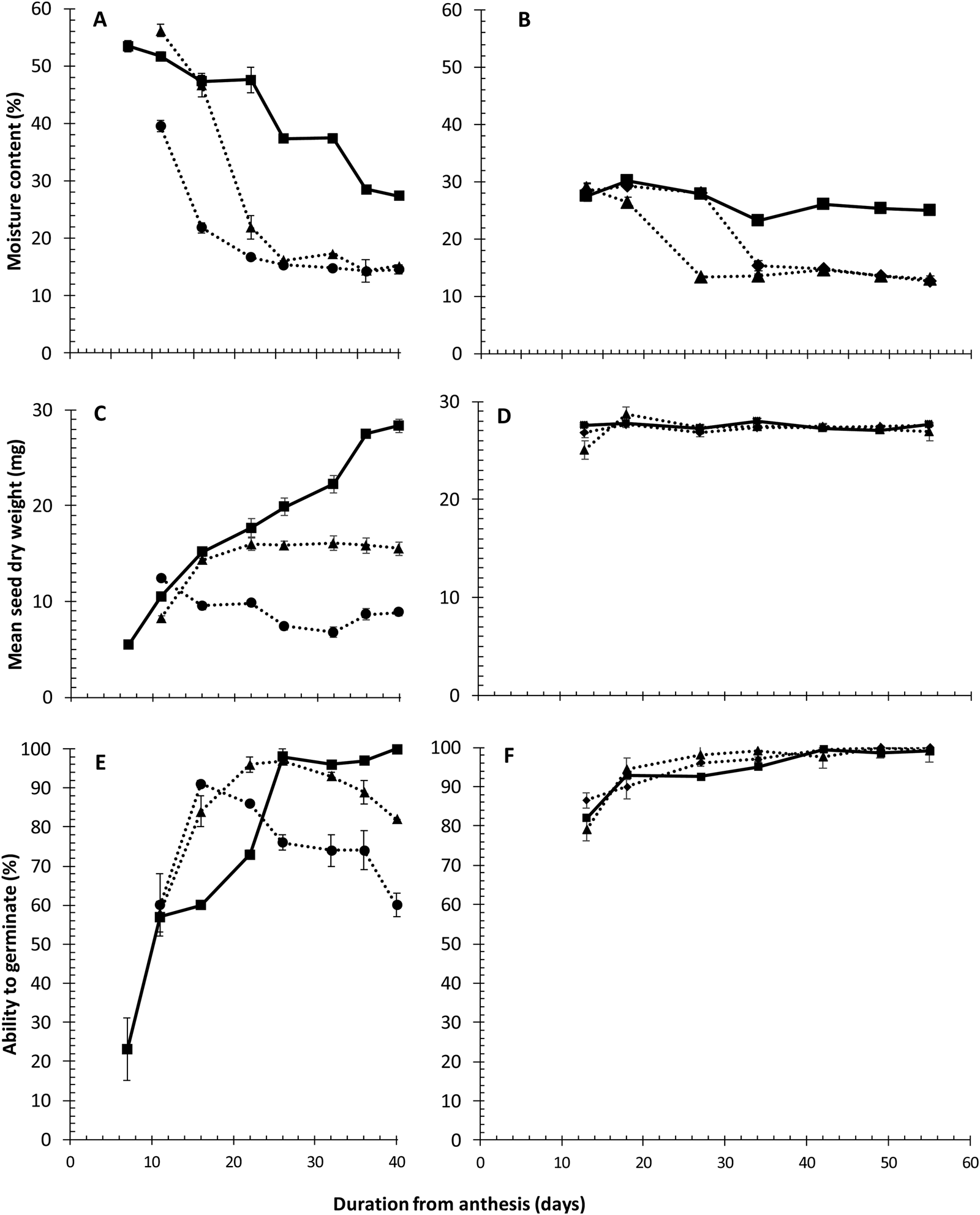

Seed moisture content at harvest at 42 DAA was similar at 25–27% in all treatments in Experiment 3, except where HT was provided in the 3 days until the mean date of anthesis (T2) where it was significantly greater at 36% (Fig. 2A). This was also the only treatment that provided significantly lower seed dry weight than the control (Fig. 2B). The ability of dried seeds to germinate approached 100% and did not differ significantly amongst treatments (Fig. 2C). High-temperature treatment 0–3 DAA (T3) and 12–15 DAA (T7) provided the lowest and most variable germination. In freshly harvested seeds, germination was lowest for HT –3 to 0 and 0 to 3 DAA (T2, T3) (data not shown).

Fig. 2. The moisture content (A), dry weight (B) and ability to germinate normally after desiccation to 10–14% moisture content (C) of seeds of Japonica rice cv. Gleva at harvest maturity (42 DAA) from plants grown in a glasshouse at 28/20°C (12 h/12 h) with 12 h day–1 photoperiod throughout (control, T1) or also exposed to 40/30°C (11 h/13 h, 11 h day–1 photoperiod) for 3 days at one of ten different periods during seed development and maturation (T2–T11). Within A and B, different lower case letters indicate a significance difference (P < 0.05) amongst treatments using Tukey's multiple range test.

Seed moisture content at 42 DAA in cvs Aeron 1 and Gleva in Experiment 4 (Fig. 3A–D) was very much lower than for cv. Gleva in Experiments 1–3. In cv. Aeron 1, differences in seed moisture content amongst treatments or cabinets were negligible (Fig. 3A,B), whereas for cv. Gleva the controls were drier as were the results for ending irrigation at 14 DAA combined with HT 14–17 DAA in Cabinet 1 and ending irrigation at 14 DAA in Cabinet 2 (Fig. 3C,D).

Fig. 3. Seed moisture content (A–D), dry weight (E–H) and ability to germinate normally after desiccation to 10–14% moisture content (I–L) of seeds of Indica rice cv. Aeron 1 (A,B,E,F,I,J) and Japonica rice cv. Gleva (C,D,G,H,K,L) at harvest maturity (42 DAA) from plants in growth cabinets (1,2) at 28/20°C (11 h/13 h) with 11 h day–1 photoperiod with irrigation throughout or ended at 14 DAA with or without brief exposure to 40/30°C (11 h/13 h, 11 h day–1 photoperiod) at either 0–3 or 14–17 DAA. Within each of A–L, different lower case letters indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05) amongst treatments using Tukey's multiple range test.

Seed dry weight was greatest in the control treatments for both cultivars in Experiment 4 (Fig. 3E–H). In cv. Aeron 1 in Cabinet 1 ending irrigation at 14 DAA combined with HT 0–3 DAA was the only treatment to reduce seed weight significantly (Fig. 3E), whereas in Cabinet 2 all stress treatments provided lower dry weight than the control (Fig. 3F). All stress treatments to cv. Gleva, in both cabinets, provided lower seed dry weight than the control with ending irrigation at 14 DAA combined with HT 14–17 DAA the lightest (Fig. 3G,H).

Ability to germinate was greater and less variable in Cabinet 1 than 2 for cv. Aeron 1 (Fig. 3I,J). Ability to germinate was poorer on average for cv. Gleva (Fig. 3K,L) than cv. Aeron 1 (Fig. 3I,J). Ending irrigation at 14 DAA combined with HT 14–17 DAA provided the poorest germination of seeds from both cabinets for each of the cultivars (Fig. 3I,L).

Four different facilities were used for each experiment, consisting of growth cabinets or glasshouses at each of two sites. The duration of the vegetative phase was much longer in the (slightly cooler) growth cabinets in artificial light (105–122 days) than in the glasshouses (76–85 days) for control plants of cv. Gleva, whereas mature seed dry weights were similar across all four experiments (Table 1). Seed moisture content at maturity was considerably lower where plant irrigation ended 7 days before harvest (Experiment 4), than in the remaining experiments where irrigation continued throughout and provided high moisture contents at maturity.

Table 1. Comparison of growth regimes, plant phenology and seed development across all four experiments (control treatments, cv. Gleva)

*DAS, days after sowing; **HM (DAA), harvest maturity, days after 50% anthesis.

Seed longevity

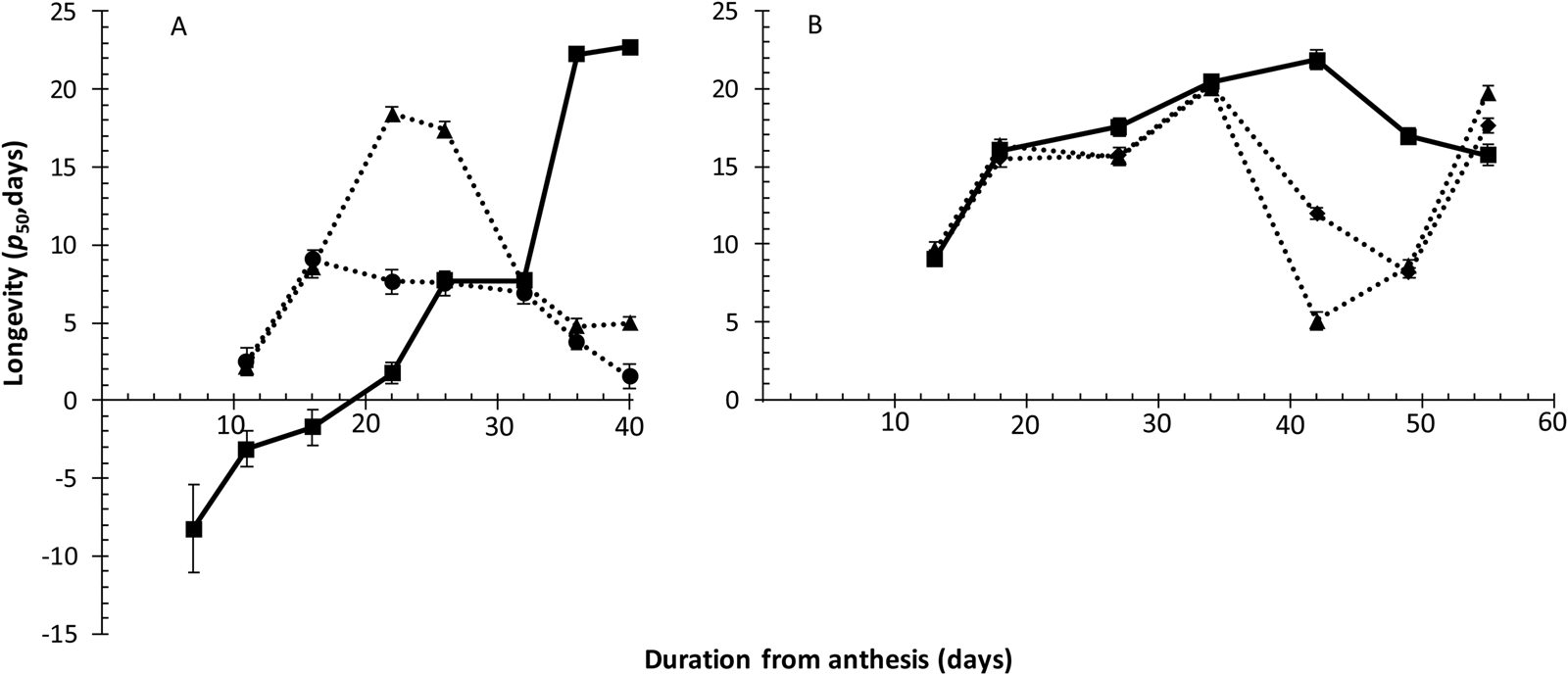

Subsequent longevity in air-dry storage increased substantially from 7 DAA onwards until the penultimate harvest at 36 DAA, with similar longevity at 40 DAA, in the control in Experiment 1 (Fig. 4A). The seed survival curve slopes (1/σ) did not differ amongst treatments at each harvest, except at 22 and 36 DAA (P < 0.05). Longevity did differ amongst the three treatments at all harvests (P < 0.05), except for the first comparison at 11 DAA (i.e. shortly after the first termination of irrigation). Longevity of seeds from droughted plants improved earlier during seed development and maturation than in the control. However, where irrigation ended at 7 DAA seed longevity plateaued between 16 and 32 DAA and declined thereafter, and where it ended 14 DAA longevity plateaued between 22 and 26 DAA (with much greater longevity than the 7 DAA treatment) and then declined. Both drought treatments provided similar, poor, longevity from 32 to 40 DAA.

Fig. 4. The longevity (p 50, estimated by probit analysis) of seeds of Japonica rice cv. Gleva harvested serially during their development and maturation from plants grown in a cabinet at 28/20°C (11 h/13 h, 11 h day–1 photoperiod) (Experiment 1: A) or a glasshouse at 28/20°C (12 h/12 h, 12 h day–1 photoperiod) (Experiment 2: B) and stored hermetically at 40°C with ± 15% moisture content. Plants were irrigated throughout ( ■ ), or only until 7 (●), or 14 (▲), or 28 DAA (♦). Vertical bars represent ± standard error of the estimate, where larger than symbols.

Seeds from the control in Experiment 2 increased in longevity with later harvests until 42 DAA (Fig. 4B); longevity declined thereafter. The pattern of improvement in subsequent longevity of seeds harvested from both drought treatments was identical and also similar to the control until 34 DAA [no difference amongst the three treatments within each harvest from 11 to 34 DAA (P > 0.05), but significant differences at all harvests from 42 to 55 DAA (P < 0.05)]. Seed longevity declined after 34 DAA in both drought treatments: rather more rapidly and considerably from 34 to 42 DAA where plant irrigation ended 14 DAA than the decline from 34 to 49 DAA where irrigation ended 28 DAA. In a further difference to the trends in the control, however, the longevity of seeds from both plant drought treatments improved amongst the late harvests – such that all three treatments provided similar longevity for seeds harvested 56 DAA.

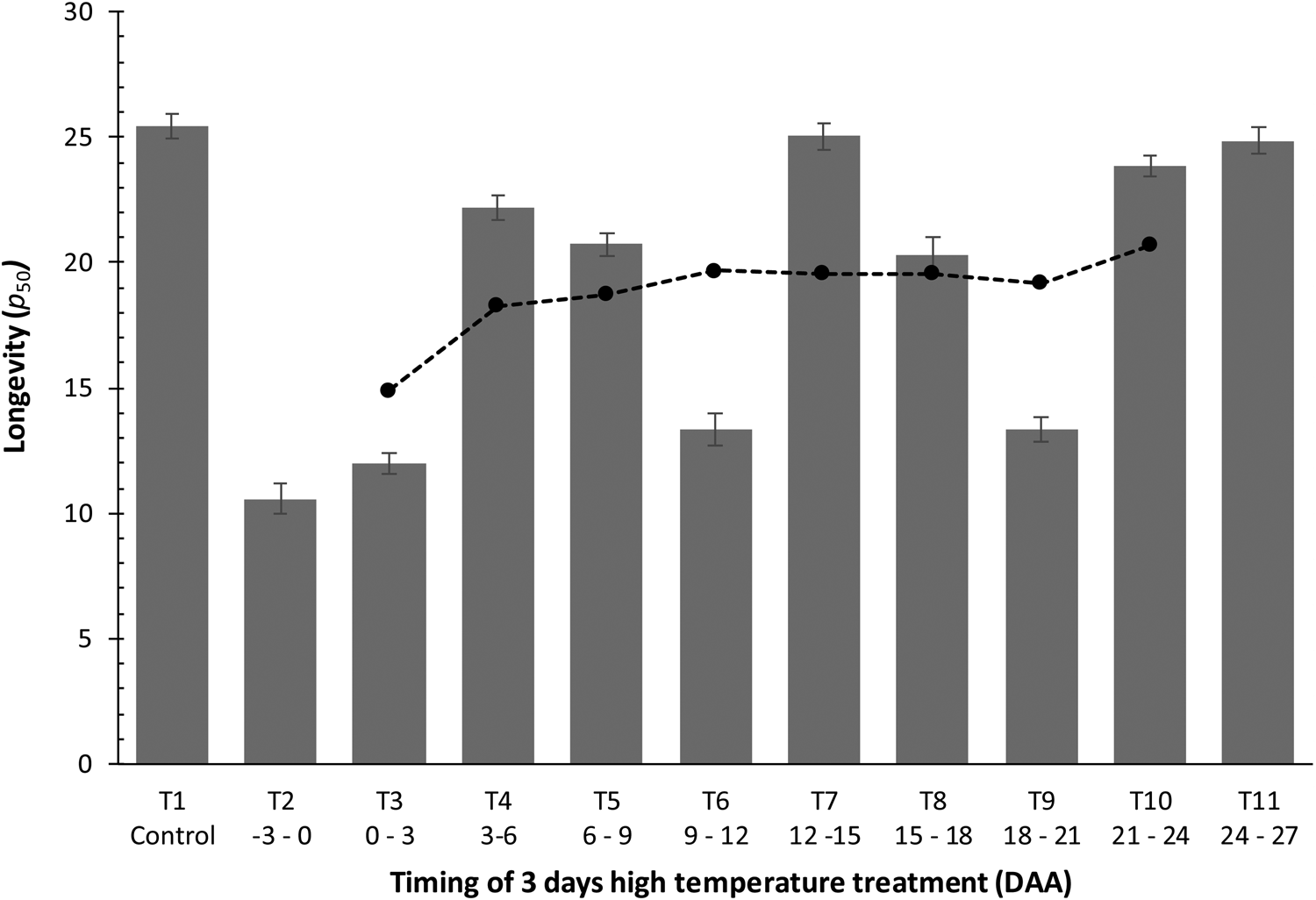

Estimates of the seed survival curve slopes (1/σ) did not differ amongst the treatments harvested at 42 DAA in Experiment 3 (P > 0.05), but longevity did (P < 0.00001). The greatest seed longevity was provided by the control, with seeds from the brief HT treatments imposed as late as 21–24 or 24–27 DAA almost as long-lived (Fig. 5). The poorest longevity was provided by the two earliest HT treatments (HT –3 to 0 DAA and 0 to 3 DAA). Intermediate timing of HT, i.e. from 3–6 to 18–21 DAA, resulted in longevity between that of the earliest two treatments and the control. There was a tendency for longevity to improve the later the 3-day HT treatment was imposed – as shown by the rolling mean. The individual estimates of longevity were more variable than indicated by the rolling means, however. The two extreme treatment timings provided values below (HT –3 to 0 DAA) or above (HT 24–27 DAA) extrapolation of the rolling means, whilst the second (HT 0–3 DAA) and penultimate (HT 21–24 DAA) were similarly below and above, respectively, the rolling means (Fig. 5). In between the earliest and latest treatments, HT 12–15 DAA provided similar longevity to the control and considerably above the rolling mean, for example, whereas for HT 9–12 or 18–21 DAA longevity was considerably below the rolling mean and closer to the two shortest-lived treatments (HT applied close to anthesis).

Fig. 5. The longevity (p 50, estimated by probit analysis) in hermetic storage at 40°C with ± 15% moisture content of seeds of Japonica rice cv. Gleva harvested at harvest maturity (42 DAA) from plants grown in a glasshouse at 28/20°C (12 h/12 h) with 12 h day–1 photoperiod throughout (control, T1) or also exposed to 40/30°C (11 h/13 h, 11 h day–1 photoperiod) for 3 days at one of ten different periods during seed development and maturation (T2–T11). Vertical bars represent ± standard error of the estimate, where larger than symbols. The filled symbols from T3 to T10 show the rolling mean of longevity (current, previous and next treatment) from anthesis onwards.

The longevity of seeds of cv. Aeron 1 harvested at 42 DAA from Cabinet 1 in Experiment 4 did not differ significantly amongst the treatments (P > 0.05): the control provided the greatest longevity and ending irrigation at 14 DAA combined with HT 14–17 DAA the briefest (Fig. 6A). In Cabinet 2 (Fig. 6B), differences in the longevity of seeds of cv. Aeron 1 were significant (P < 00001). Longevity was similar to that in Cabinet 1 and also similar amongst all but one treatment: HT at 14–17 DAA provided much greater longevity. The combined stress of ending irrigation at 14 DAA with HT 14–17 DAA resulted in the briefest longevity.

Fig. 6. The longevity (p 50, estimated by probit analysis) of seeds of Indica rice cv. Aeron 1 (A,B) and Japonica rice cv. Gleva (C,D) from plants grown in cabinets (1,2) at 28/20°C (11 h/13 h, 11 h day–1 photoperiod) with irrigation throughout or ended at 14 DAA with or without brief exposure to 40/30°C (11 h/13 h, 11 h day–1 photoperiod) at either 0–3 or 14–17 DAA, harvested 42 DAA and stored hermetically at 40°C with 15% moisture content. Vertical bars represent ± standard error of the estimate, where larger than symbols. The seed survival curves provided by probit analysis to estimate p 50 are quantified in Supplementary Table 1, together with the seed storage moisture content for each curve.

Seed longevity of cv. Gleva (Fig. 6C,D) was more damaged by the stress treatments than cv. Aeron 1 (Fig. 6A,B). The longevity of seeds of cv. Gleva differed significantly amongst treatments in both cabinets (P < 00001). It was greatest in the control in each cabinet, considerably reduced in all five stress treatments, and least where irrigation ended 14 DAA was combined with HT 14–17 DAA (Fig. 6C,D). In this cultivar, HT stress alone and drought alone also reduced longevity below that of the control.

Discussion

Drought and high temperature episodes are often concurrent in the field, but their effects on crops and seeds tend to be investigated separately. This was the case in three experiments here, whilst both were investigated together in the final experiment. Modifying each environmental variable affected the temporal pattern of seed development and maturation in terms of seed moisture content, dry weight and seed quality. In flooded rice (paddy) cultivation, water supply generally ends about 7–10 days before harvest (Bouman et al., Reference Bouman, Lampayan and Tuong2007) – provided sufficient water is available until then – and so much later than the plant drought treatments imposed here. Whilst the effects of high temperature detected here are relevant to all rice production systems, those of drought are therefore more relevant to rainfed and upland rice systems.

The control environments varied across the four experiments and this affected plant development (Table 1). The light environment varied considerably between growth cabinets and glasshouses, a rectangular profile (lights on or off) in the former and a curved profile (sun rises and sets) in the latter (and in both cases less light than would be received in field experiments). Results in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) suggest that differences in incident radiation affect final seed dry weight but not subsequent seed longevity (Pieta Filho and Ellis, Reference Pieta Filho and Ellis1991). There were other differences in seed development and maturation across the four experiments. In particular, seed moisture content at harvest was low in Experiment 4, because the irrigation of all plants had ended earlier. At the other extreme, where irrigation continued until the end of the experiment seed moisture content remained high (e.g. controls in Fig. 1A,B). The latter values are similar to those for mature rice seeds harvested in the field in flooded rice cultivation (Whitehouse et al., Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2015). Rice seed moisture content at maturity appears to vary more with ambient environment than is the case in other cereals. Despite such differences amongst experiments in seed production environment and the dynamics of seed filling and desiccation, consistent effects of treatments were detected.

Drought (plant irrigation ended early) resulted in more rapid seed development including more rapid decline in seed moisture content, an earlier end to seed filling, and reduced seed dry weight (e.g. Fig. 1). The latter is a common consequence of drought stress during the reproductive phase in rice (e.g. Zakaria et al., Reference Zakaria, Matsuda, Tajima and Nitta2002; Kato et al., Reference Kato, Satoshi, Akiniko, Abe, Urasaki and Yamagishi2004; Sikuku et al., Reference Sikuku, Netondo, Onyango and Musyimi2010; Sabetfar et al., Reference Sabetfar, Ashouri, Amiri and Babazadeh2013; Dasgupta et al., Reference Dasgupta, Das and K-Sen2015). Brief exposure to high temperature early in the reproductive phase may also reduce rice seed dry weight (e.g. Prasad et al., Reference Prasad, Boote, Allen, Sheehy and Thomas2006; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Shon, Lee, Yang, Yoon, Yang, Kim and Lee2011; Martínez-Eixarch and Ellis, Reference Martínez-Eixarch and Ellis2015; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Yin, Struik, Xie, Schmidt and Jagadish2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Chang and Lur2016), as detected here when applied close to anthesis (e.g. Fig. 2). Combining drought with high temperature stress resulted in greater reduction in seed dry weight than each stress alone in the Japonica cv. Gleva (Fig. 3G,H), whereas Indica cv. Aeron 1 was less severely affected (Fig. 3E,F).

Exposing rice plants to each of drought and/or high temperature during the reproductive phase damaged subsequent seed quality, but this varied between cultivars and with treatment timing. Some evidence of such damage was detected in the Indica cv. Aeron 1 (e.g. Fig. 3I,J), but seed quality in the Japonica cv. Gleva was more vulnerable to damage from these stresses (Fig. 3K,L; Fig. 6C,D). In rice, Japonica cultivars often show poorer seed storage longevity than Indica cultivars (Chang, Reference Chang1991), as here (Fig. 6), whilst damage to seed quality from higher temperature seed production regimes is more likely in Japonica than Indica cultivars (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Hong and Jackson1993; Ellis and Hong, Reference Ellis and Hong1994; Rao and Jackson, Reference Rao and Jackson1996, Reference Rao and Jackson1997).

Variation amongst panicles in the timing of anthesis was greater than the duration of each of the brief high temperature episodes in Experiment 3. The rolling mean for longevity and most individual observations showed that these 3-day HT treatments were more damaging to rice seed quality close to anthesis compared with later in seed development in cv. Gleva, but with poor longevity also detected with HT at 9–12 or 18–21 DAA (Fig. 5). Hence some damage from HT was detected until towards the end of the seed-filling phase (from comparison with other experiments), but was particularly severe around anthesis and histodifferentiation, mid-seed filling, and late seed filling/early maturation drying. Similarly in Experiment 4, seed longevity in cv. Gleva was reduced by HT at 0–3 and at 14–17 DAA (anthesis and histodifferentiation, and mid- to late-seed filling), but when combined with late drought stress (from 14 DAA) more at 14–17 than at 0–3 DAA (Fig. 6C,D). This confirms the earlier general suggestion that such damage to Japonica rice seed results from exposure to high temperature before maturation drying (Ellis, Reference Ellis2011). Our results are also in broad agreement with those where most damage to Japonica rice seed coincided with exposure to HT at anthesis and histodifferentiation, with some damage also detected from HT just before anthesis and at mid-late seed filling (Martínez-Eixarch and Ellis, Reference Martínez-Eixarch and Ellis2015). The most sensitive period to brief HT for subsequent seed quality was from anthesis to midway through seed filling in wheat also with yet greater damage from HT from a longer-duration treatment (Nasehzadeh and Ellis, Reference Nasehzadeh and Ellis2017).

The earliest drought treatment provided here was later than anthesis and was progressive from when irrigation ended. Drought accelerated seed development and maturation but also damaged seed quality development, such that maximum quality was reduced, and the earlier drought was imposed the greater this damage (e.g. Figs 1E, 4A). As with high-temperature stress, seed quality of the Japonica cv. Gleva was more vulnerable to drought stress than the Indica cv. Aeron 1. The literature on the effect of drought during seed development and maturation on seed quality is less extensive than that for high temperature. Drought accelerated seed quality development in B. campestris with a small improvement in maximum longevity (Sinniah et al., Reference Sinniah, Ellis and John1998a), whereas it reduced ability to germinate after harvest in soya bean (Smiciklas et al., Reference Smiciklas, Mullen, Carlson and Knapp1989) and pea (Fougereux et al., Reference Fougereux, Dore, Ladonne and Fleury1997), or after accelerated ageing in barley (Samarah and Alqudah, Reference Samarah and Alqudah2011), soya bean (Vieira et al., Reference Vieira, Tekrony and Egli1991), pea (Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, Warrington and Scott1978), and wheat (Tarawneh et al., Reference Tarawneh, Szira, Monostori, Behrens, Alqudah, Thumm, Lohwasser, Röder, Börner and Nagel2019).The temporal patterns and sequence of seed development and of seed quality development in most treatments (Figs 1, 4) and previous investigations in rice (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Hong and Jackson1993; Ellis and Hong, Reference Ellis and Hong1994; Tejakhod and Ellis, Reference Tejakhod and Ellis2018) were broadly similar. Seed quality continued to improve after the end of the seed filling phase in both drought treatments in Experiment 1 and all treatments in Experiment 2, but the control treatments differed between experiments. The Experiment 1 control showed delayed loss in moisture (Fig. 1A,B), an extended period of seed filling (Fig. 1C,D), later development of ability to germinate (Fig. 1E,F), and slower development of post-harvest, air dry longevity (Fig. 4) than Experiment 2 – or previous studies. Water stress shortens the period of seed filling because it regulates the cessation of seed growth (Egli, Reference Egli1998), as here (Fig. 1). Within a genotype, there is no pre-determined duration of seed filling – it is dependent upon the within-seed environment (Egli, Reference Egli1998). Control seeds in Experiment 1 were wetter than those of Experiment 2 at 14–40 DAA (Fig. 1A,B); hence the former's longer period of seed filling.

Despite differences in seed desiccation and filling between the controls, both these experiments provided a clear effect of plant drought on seeds. Imposing drought on plants in Experiment 1 resulted in earlier development of seeds’ ability to germinate but also (later on) an earlier decline (Fig. 1E); and greater earlier improvement in subsequent seed longevity but also earlier decline than the control thereafter (Fig. 4A). In Experiment 2, seeds from droughted plants did not lose moisture until after the seed filling phase when the development of ability to germinate was almost complete, which is when the treatments were imposed (Fig. 1B,D,E). Nonetheless, subsequent seed longevity declined before the control (Fig. 4B). Differences in the pattern of increase and then decline in subsequent longevity, earlier than in the control, were a consequence of the drought treatments and earlier seed desiccation, despite no effects on either seed filling or the development of ability to germinate. In both experiments the sequence of results corresponded with that for ending irrigation, as reported for B. campestris (Sinniah et al., Reference Sinniah, Ellis and John1998a). These findings on the impact of drought on rice seed quality from controlled environment studies require independent appraisal in field studies, particularly in regions with upland rice production systems.

Earlier predictions of rice seed storage longevity (σ) (Ellis and Hong, Reference Ellis and Hong2007) provided good agreement in a recent study with results for Indica but over-estimated those for Japonica rice (Tejakhod and Ellis, Reference Tejakhod and Ellis2018). On the other hand, Whitehouse et al. (Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2018) found that the independent predictions generally over-estimated σ for all rice cultivars investigated. The latter was also the case here: a few observations were close to the predicted values but the majority were considerably lower, with estimates of σ = 2–12 days compared with predictions of σ = 11–15 days for the 80 seed lots (Supplementary Figure 1). Absolute longevity (p 50) was generally good in the better production regimes (e.g. mature seed controls) for the storage environment (e.g. at 40–42 DAA in Fig. 4A), but variability in survival periods amongst individuals within each seed lot was limited and hence the small estimates of σ.

The durations of embryogenesis and seed development are minor compared with that of late seed maturation, particularly in rice (Leprince et al., Reference Leprince, Pellizzaro, Berriri and Buitink2017). That was the case here, except for one unusual result (Experiment 1 control). The major events and regulatory pathways during late seed maturation affect subsequent ability to germinate, tolerate desiccation, and longevity, including chlorophyll degradation and the accumulation of raffinose family oligosaccharides, late embryogenesis abundant proteins, RNA and heat-shock proteins (Sinniah et al., Reference Sinniah, Ellis and John1998b; Chatelain et al., Reference Chatelain, Hundertmark, Leprince, Gall, Satour, Deligny-Penninck, Rogniaux and Buitink2012; Leprince et al., Reference Leprince, Pellizzaro, Berriri and Buitink2017; Dirk and Downie, Reference Dirk and Downie2018).The number of different pathways, together with differences in the timing of when they are most active (e.g. Sinniah et al., Reference Sinniah, Ellis and John1998b), may help to explain why brief HT damaged subsequent longevity to differing extents when applied at different times in Experiments 3 (Fig. 5) and 4 (Fig. 6).

This is relevant to the drought treatments which coincided with late seed maturation here, and in some cases with seed filling, whereas high temperature was not damaging in late seed maturation. The latter tallies somewhat with several ex planta studies where brief high temperature in late seed maturation increased rice seed longevity (Whitehouse et al., Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2015, Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2017, Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2018). Earlier in development, high-temperature treatment during embryogenesis at 39°C for 24–72 hours just after fertilization disrupted endosperm development in rice, producing irregular-shaped small seeds, and also reduced viability substantially, whilst at 35°C the regulation of abscisic acid and gibberellin biosynthesis genes was perturbed (Begcy et al., Reference Begcy, Sandhu and Walia2018). Treatment at 40°C was less damaging here than that at 39°C in that research, perhaps because it was provided in a diurnal cycle for only 11 or 12 h day–1.

In Experiment 2, seed harvests were extended well beyond normal harvest date (in rice seed production, harvest would not be so delayed because seeds would be shed or damaged by wind, rain or rats). We delayed harvest considerably in order to determine whether, and if so when, seed longevity in the control began to decline in planta after harvest maturity. This was indeed the case, but most surprisingly the earlier decline in seed longevity in the two drought treatments was then reversed by 49–55 DAA (Fig. 4B). We cannot explain this reversal. It might be erroneous, but the results were consistent: it was detected in both drought treatments; in the greater drought stress the positive trend was consistent across three observations (42, 49, 55 DAA; Fig. 4B); the opposite trend was detected in the control over this period; and ability to germinate was close to 100% throughout this period (Fig. 1F). In other studies close to harvest maturity, subsequent seed longevity has been improved by dehydration after brief seed rehydration in planta in wheat (Ellis and Yadav, Reference Ellis and Yadav2016; Yadav and Ellis, Reference Yadav and Ellis2016) and by brief high-temperature drying treatments to moist (>>16% moisture content) rice seed ex planta (Whitehouse et al., Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2015, Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2017, Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2018). In our study, seed moisture content was then (42–55 DAA) low (12.6–13.6%, Fig. 1B). The former explanation is therefore not appropriate, but Whitehouse et al. (Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2015, Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2017, Reference Whitehouse, Hay and Ellis2018) did report some benefit to rice seed longevity from brief periods of warmer temperature ex planta at harvest maturity in drier (<16% moisture content) seeds.

Evaluating the potential impacts of climate change over the remainder of the 21st century (IPCC, 2014) on future rice production includes a need to account for the coincidence of environmental extremes with vulnerable stages of crop phenology. If high day temperatures (Jagadish et al., Reference Jagadish, Craufurd and Wheeler2007) and/or high night temperatures (Coast et al., Reference Coast, Ellis, Murdoch, Quiñones and Jagadish2015) coincide with anthesis in rice then seed set is damaged which reduces crop yield. The current results emphasize that seed quality in rice is also damaged by a similar temporal coincidence of environmental extremes with phenology: seed quality is particularly sensitive to damage from brief episodes of high-temperature and/or drought if they coincide with anthesis or shortly afterwards.

Acknowledgements

We thank Caroline Hadley, Val Jasper, Laurence Hanson, Liam Doherty, Matthew Richardson and Tobias Lane for technical support.

Financial support

This research was supported by a scholarship to S.M.A.R. from the Fellowship Program of Skim Latihan Akademik Bumiputera (SLAB) funded by the Minister of Higher Education, Malaysia, and Universiti Teknologi Mara.

Supplementary Material

To view Supplementary Material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960258519000217