Dancer and historian Irmgard Bartenieff remarked in 1963, “Dance notation is not an invention of modern times. Like music notation, it has a history extending over several centuries” (Reference Bartenieff1963, 2). Both now and at midcentury when Bartenieff was active, most people with any knowledge of dance notation, either within or outside the field of dance, would point to the early twentieth-century choreographer and scholar Rudolf von Laban as the primary figure in the development of dance notation. His highly systematized and abstract notation method, known as Laban Kinetography, or Labanotation, provides a comprehensive means to record both dance and ordinary movement, but it is hardly the genesis of dance notation. The first substantive, fully developed systems of dance notation emerged in the late seventeenth century in France and Germany. In the first incarnations of dance notation, debates arose among dance teachers and choreographers (known as “dancing masters,” in the era’s parlance) about the formal and creative implications of dance notation, conflicts that ultimately contributed to the waning of dance notation’s popularity.

Dance notation originally arose out of the French court, where dance played a highly important role for nobility as well as courtiers. King Louis XIV himself performed dances at court, and elegance and grace in performance were highly revered qualities for both a ruler and his subjects. The dance notation system that ultimately attained precedence, Beauchamp-Feuillet notation, was commissioned by Louis XIV, apparently intended as another element of cultural achievement to augment the glory of the Sun King’s reign. In the Baroque era, social dance and stage dance were strongly interlinked in France, with dances performed on stage being the same as or highly similar to those dances performed socially.Footnote 1 Prior to the Baroque invention of dance notation, dance was an art taught and transmitted almost exclusively through bodily communication, that is, conveyed both orally and through physical movement. While notes about scenography or costuming could be readily conveyed and easily comprehended on paper, written notes about choreography would require human interpreters to actualize. Once the notation system commissioned by Louis XIV was in place, dancing masters were able to communicate to new, physically distanced audiences the steps and movements of popular dances of the day, as well as their own creations. With the first publications of French dances, the conveyance of choreography was no longer exclusively achieved through the human body and voice but could be transported by the printed page as well.

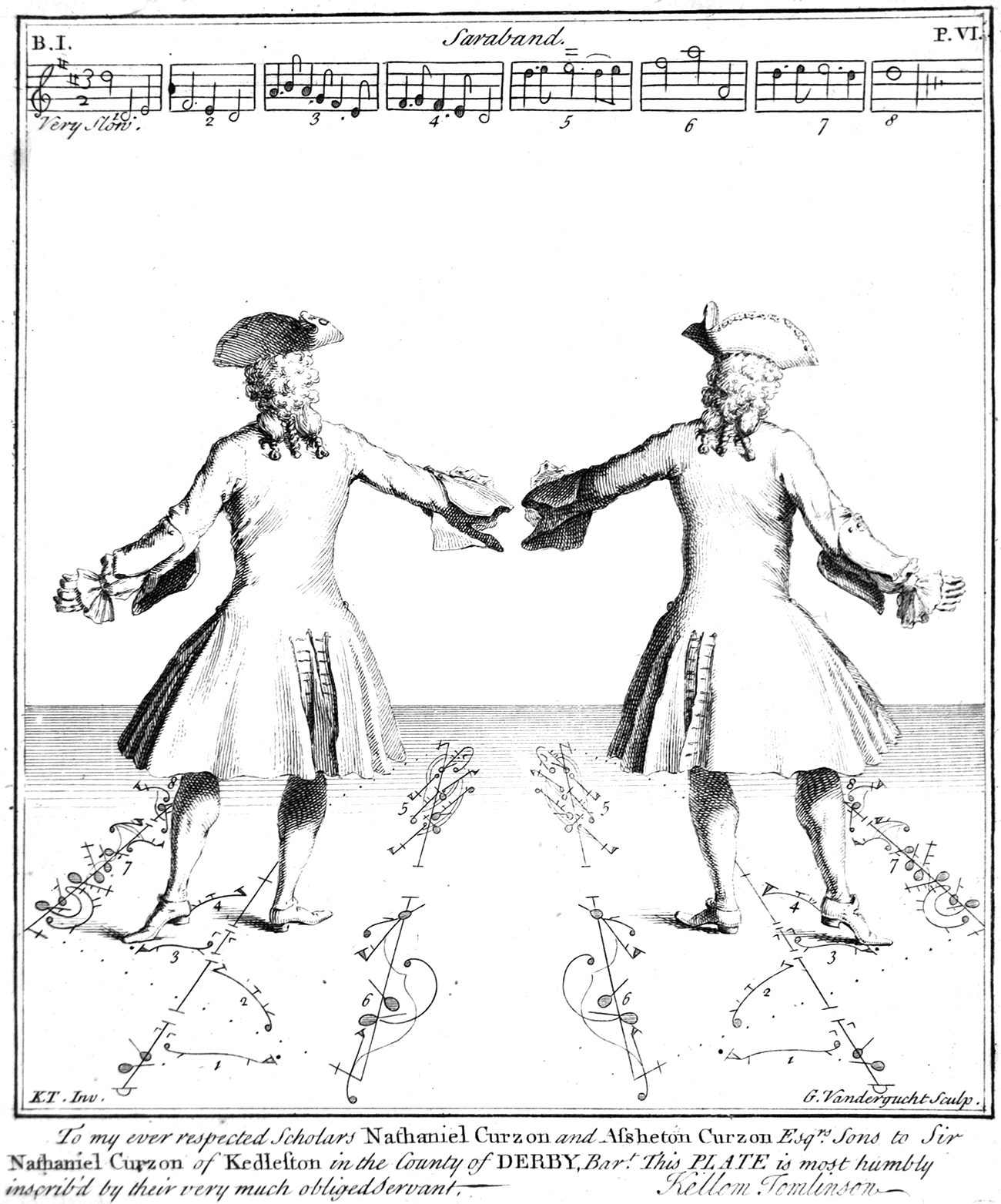

In the first decades of the eighteenth century, translations of the French dancing masters’ texts were published in London, and English dancing masters added their unique compositions and notational variations to the printed corpus of Baroque dance notation. This article surveys the emergence and significance of the primary system of dance notation in the Baroque era and examines the appearance of French notation and dance composition in English-language translations, and specifically investigates one unique published example of dance notation, Kellom Tomlinson’s 1735 work The Art of Dancing Explained by Reading and Figures. Written in an augmented form of Beauchamp-Feuillet notation with detailed figural illustrations, Tomlinson’s The Art of Dancing was both the apotheosis and swan song of dance notation of the Baroque era.

History of Dance Notation

As with any system of notation or representation, dance notation engages in varying levels of abstraction. Unlike standard musical notation, which is an entirely disembodied, abstract form of notation that maintains no direct reference to physical objects or space, early dance notation utilizes iconographic representational elements that can be recognized as components of the physical world. Chiefly the most recognizable of such elements is the correlation of page space to the space of the dance floor. As will be discussed in further detail below, additional recognizable elements can be viewed in notation of the Baroque era.

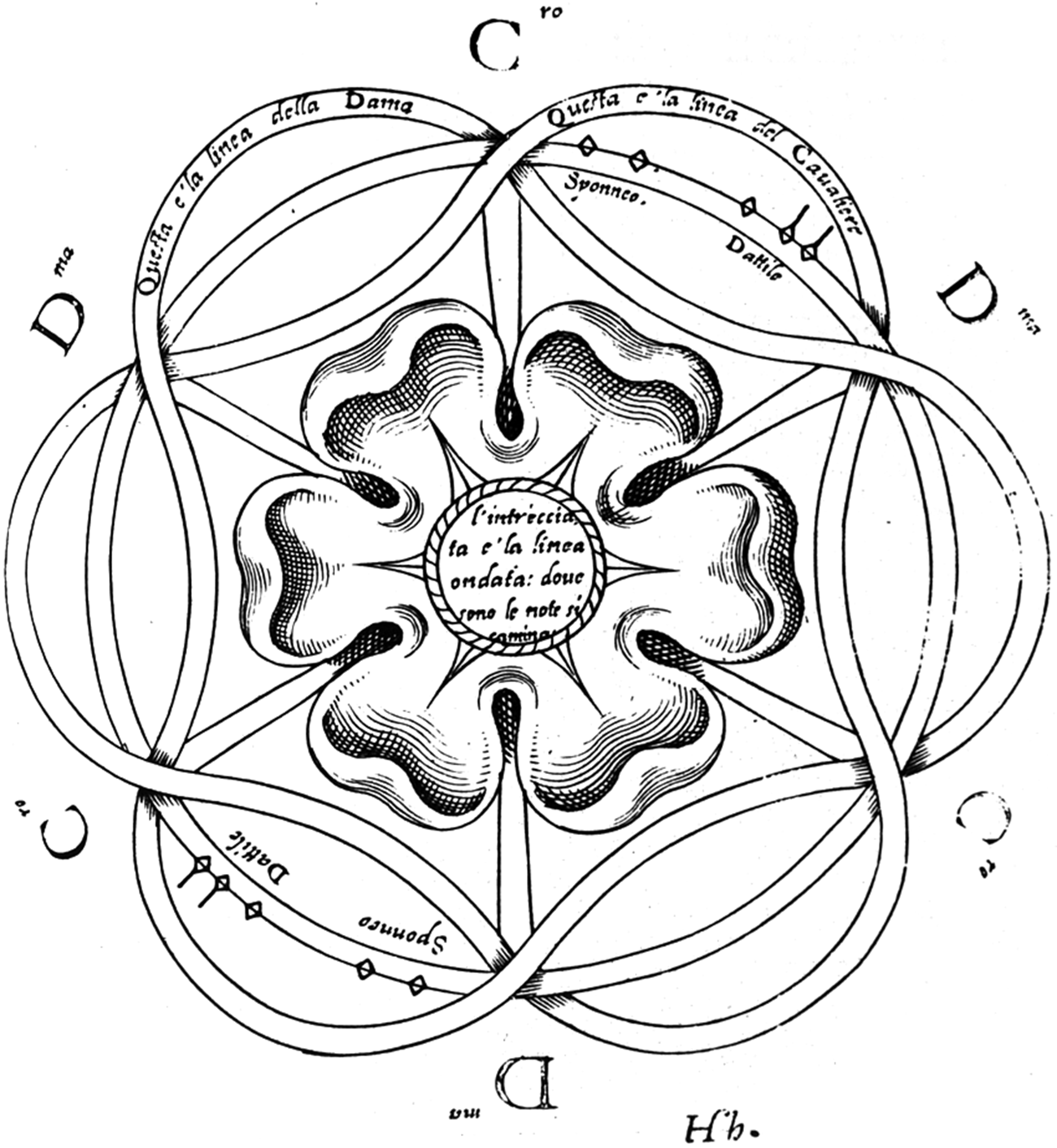

As the Baroque choreographic repertoire and Baroque dance notation began to emerge through the work of Pierre Beauchamp and Raoul-Auger Feuillet, both masters of performance and of notation, the emphasis on the floor plane and movement path tracings established during the Renaissance remained constant and highly important. The earliest known forms of dance notation that arose during the Renaissance were defined by the tracing of dancers’ paths across the floor onto a surrogate of the floor in the form of a leaf of paper. In some cases those recorded paths might define the contours of a plan-view image, one example of which is the almost mystical-seeming image of the rose pattern from Fabritio Caroso’s Nobiltà di Dame of 1600 (see fig. 1).

Figure 1. The rose-shaped floor pattern traversed by the dancers in Fabritio Caroso’s Nobiltà di Dame ([1600] Reference Caroso, Sutton and Marian Walker1986; reproduced in Guest 1990, 204).

An exemplary case such as this shows the primacy of the danced or notated path as seen in plan, a choreographic feature that is not readily visible from the perspective of a spectator or audience member viewing the dance in performance. Other early examples of dance notation are characterized by either their indication of points on the floor occupied by performers at a particular moment or by the lines traced by the movement paths of dancers throughout the duration of a work. In addition to this, written description often would have accompanied such tracings or point maps; and generally speaking, no dance documentation or notation, when viewed alone, would have provided sufficient information to restage a dance, until the introduction of Beauchamp-Feuillet notation, which began to approach completeness of representation for the first time.

The development of a systematic movement representation scheme either requires a complex, abstract, highly detailed system of representational elements to accommodate every possible movement variation, or the system itself must have a narrower scope of representational aims, a more limited intent for communication, and a smaller movement lexicon. The dominant notation scheme of the Baroque era fell into the latter category and represented only those movements already established in the dance vocabulary of the day.

In his history of French dance notation of the late seventeenth century, Ken Pierce (Reference Pierce1998, 287) describes several rival dance notation systems that emerged nearly concurrently in France, with no shortage of disputes between their respective authors. These disputes were not merely moral or interpersonal, but extended to lawsuits brought up for judgment in French courts. Only one name became inextricably associated with Baroque dance notation, that of Raoul-Auger Feuillet, whose seminal Choréographie was published in 1700. Feuillet, however, is commonly held not to be the inventor of the notation scheme that now bears his name, but rather he is recognized as the first person who documented and published (and perhaps also adapted and modified) the notation system developed by Pierre Beauchamp, a French ballet master affiliated with both the Paris Opera and the court of Louis XIV. Beauchamp had been commissioned by the king to develop a method for notating and recording dances; or, in Pierce’s words, “Sometime around 1674 Louis XIV ordered Pierre Beauchamp, dance director at the Académie Royale de Musique (the Opéra) and Louis’s dancing master, to find a way to put dance on paper. … We do not know whether Louis gave a reason for this order, beyond the formulaic ‘Car tel est notre plaisir’” (287).

Beauchamp was responsible for devising and developing the system later known as Feuillet notation, and indeed he was recognized in one of the lawsuits mentioned above as the creator of said notation system, but it was Feuillet who popularized Beauchamp’s notation method through an energetic agenda of notating, publishing, and circulating printed dances. Choréographie is Feuillet’s best known and most translated work. With this work and those that followed shortly after, Feuillet facilitated the transmission of French ballet choreography and of Beauchamp’s notation system to a geographically dispersed audience across Europe and England. In 1706 two English translations of Choréographie were published in England by two different dancing masters active at the time. A version entitled The Art of Dancing was published by P. Siris, about whom little is known (Thorp Reference Thorp1992); the other was titled Orchesography, or the Art of Dancing, by John Weaver, who was well known in English stage dance and private dancing instruction. Of the two versions, Weaver’s translation appears to have become more popular for reasons possibly related to personal influence. Weaver’s version of Feuillet’s text was accompanied by an additional original text by Weaver titled “A Small Treatise of Time and Cadence in Dancing, Reduced to an Easy and Exact Method Shewing How Steps, and their Movements agree with the Notes, and the Division of Notes, in each Measure.” As Weaver explains, this exposition was missing from Feuillet’s original text, and the simple insertion of numbers correlated between the musical notation and the dance notation enables the clarification of steps. This notational evolution was not the invention of Weaver, but rather was presented by Feuillet himself in his 1704 work “Recueil de Dances,” a collection of ballets composed by Louis-Guillaume Pécour and notated by Feuillet, which Weaver notes that he found enlightening in the preparation of his treatise.

Feuillet’s influential first publication presents, in a somewhat dry, matter-of-fact manner through tables, diagrams, and textual description, the full range of movements commonly utilized in Baroque dance. The space of the dance floor, as mentioned above, is represented either by a rectangle set within the page or by the page space itself, always oriented with the top of the page, or top of the rectangle, as the front of the room, where the figure of nobility or rank would be seated. To quote from Weaver’s translation, “You must understand, that each Page, on which the Dance is described, represents the Dancing-Room; and the four Sides of the Page, the four Sides of the Room, viz. The upper part of the Page, represents the upper end of the Room; the lower part, the lower end; the right side of the Page, the right side of the Room; and the left side, the left” (Weaver Reference Feuillet and Weaver1706, 34). Feuillet’s representation of the foot presents another element that is relatively recognizable from its real-life counterpart (fig. 2). The feet are represented as heel and angle of foot, with a circle for the heel and an extended line for the direction of the toes. The basic foot positions, divided into “true positions” (toes pointing outward) and “false positions” (toes pointing inward), are the basis of the foot positions still used in ballet of the current day, although the so-called false positions are no longer part of common ballet vocabulary.

Figure 2. Feuillet’s table of bourrée steps, as printed in Orchesography (1706), John Weaver’s translation of Feuillet’s Choréographie (1700).

Feuillet’s system of notation, as laid out in Choréographie and in Weaver’s translation, includes over forty tables of precisely defined steps and foot movements. Weaver’s translated tables reproduced those of Feuillet nearly identically, replacing French with English, although many movement terms were simply imported (bourrée, pirouette, etc.) rather than translated. As Wendy Hilton notes, “At first glance, it seems that the vocabulary of steps was enormous, but Feuillet is showing every possible variation of each step as well as the different ways of notating each variation. There are ninety-four examples of pas de bourrée, each drawn to account separately for execution with the left or the right foot” (Reference Hilton1997, 47) The textual portion of the book, roughly forty pages long, is written with plodding detail but some lack of clarity for a reader unfamiliar with the era’s customary dances.

Feuillet’s notation system reached predominance quickly, and the first two decades of the eighteenth century saw numerous publications in dance notation. John Weaver, the translator of Feuillet mentioned above, was among those dancing masters who published regularly during these years. In the early eighteenth century, the ability to read dance notation was considered to be a necessary complementary skill when learning to perform the social dances of the day. In eighteenth century society, dancing held a place of prominence for which there is little equivalent today. As Eric McKee (Reference McKee2011, 2) states in his study of the minuet and waltz in this era, “The ubiquity and far-reaching influence of social dancing in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries cannot be overestimated. The activity of dancing was a vital part of social life and was without question the most common form of social entertainment. … For the lower classes, dancing provided a diversion from the toils of the day; the upper classes used it as a way of defining themselves individually within their class and collectively apart from the lower classes; and for all levels, the activity of dancing was a vehicle for courtship, ceremonies, and celebrations.” Among the upper classes, learning to read dances seemed to be nearly as important as learning to perform the dances themselves. As Ann Hutchinson Guest states, “Dance literacy was an expected skill of an educated man. Indeed, one reads of complaints from the clergy of ladies having books of dances instead of Bibles on their bedside table” (Reference Guest1990, 64).

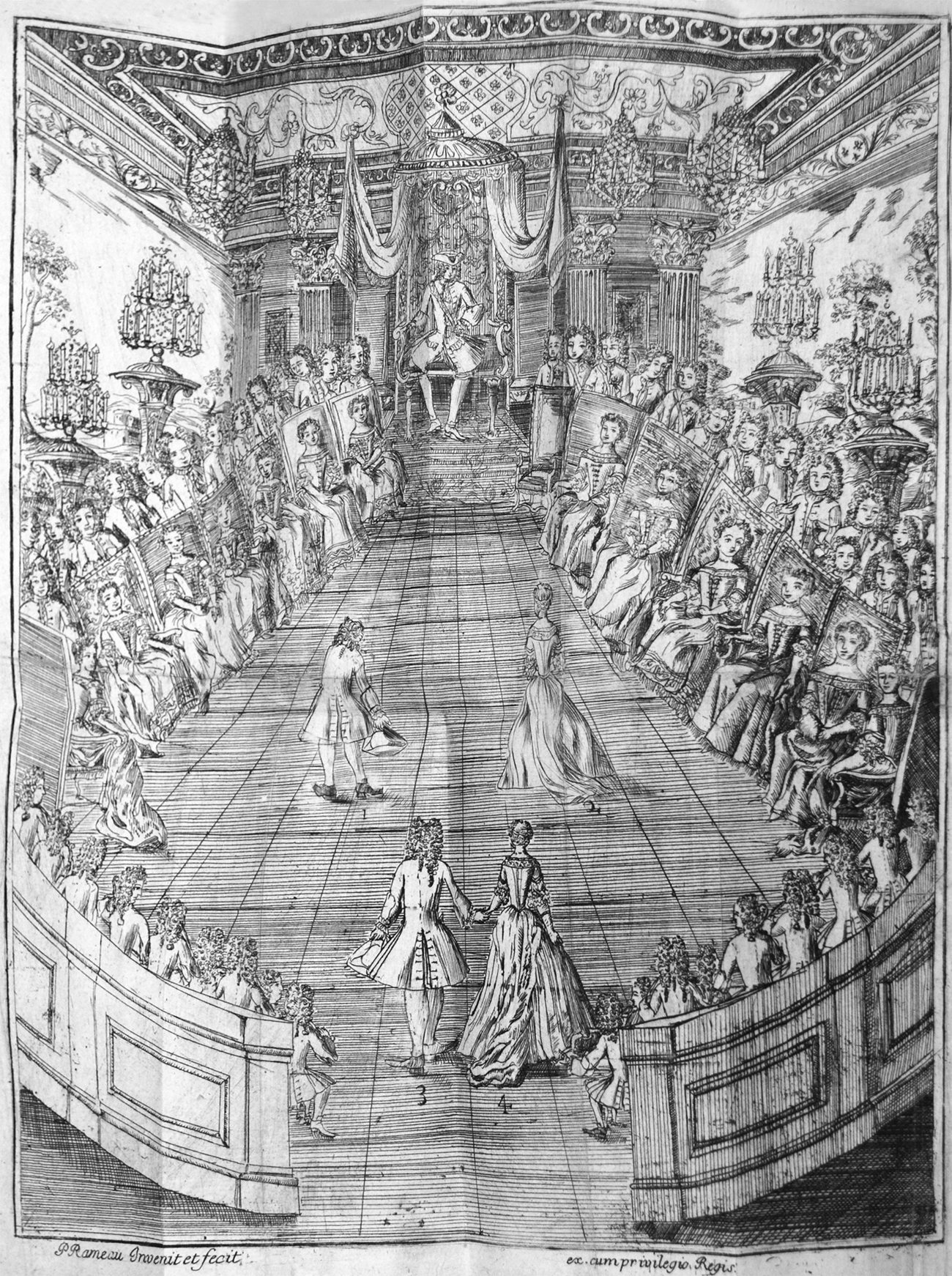

In this era of dance literacy mania, another influential French publication hit the London scene by way of Pierre Rameau’s new work titled Le Maître à Danser, published in Paris in 1725. Rameau’s book committed numerous pages to elucidating the positions and movements of the dancer’s arms, a topic relatively unaddressed by Feuillet in his influential text of two decades earlier. Also in contrast to Feuillet’s seminal work, Rameau’s text included illustrated plates of human figures performing the positions and movements; human figures were not included in Feuillet’s work. Rameau also provides readers with a glimpse of the performance and viewing experience of the era’s dances through inclusion of an oversized illustrated plate included in Le Maître à Danser (fig. 3). Rameau’s detailed depiction of the dancing room supplies the visual context into which readers can imagine the isolated figures and diagrams that punctuate Rameau’s text.

Figure 3. Oversized illustrated plate of the dancing room, from Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître à Danser (1725).

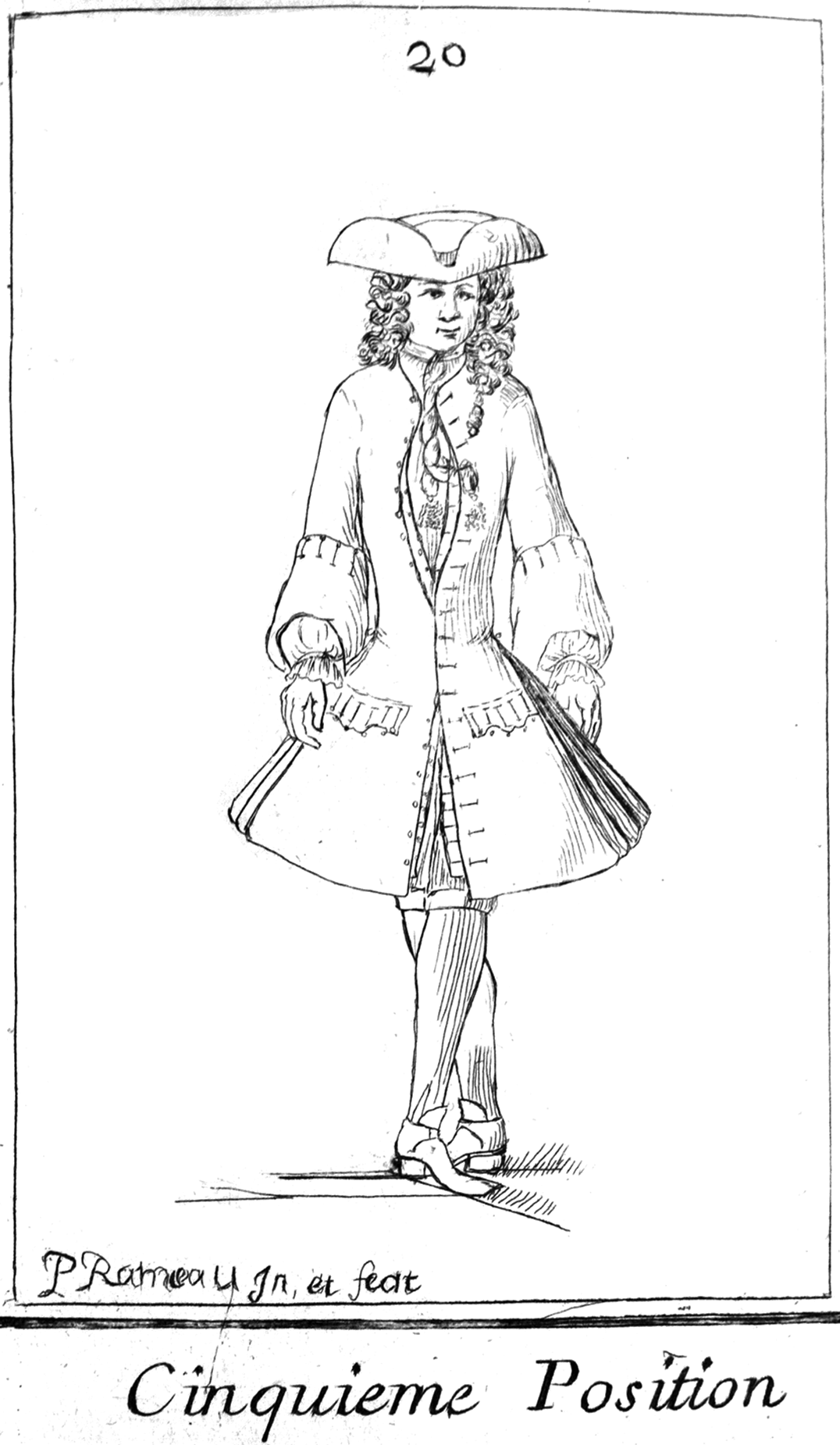

The illustrated plates of etchings included in Le Maître à Danser were delineated by Rameau himself; while his depictions of the human figure might be kindly characterized as naïve, the illustrations were also entirely sufficient for the purpose. The unembellished lines and smiling countenance of Rameau’s figures provide a pleasant counterpoint to the rather dry text (fig. 4).

Figure 4. A demonstration of the fifth foot position, in Le Maître à Danser (1725), plate 20.

An English translation of Le Maître à Danser was published in London by John Essex in 1728 (a second edition followed in 1731), with the title The Dancing-Master: Or, the whole art and mystery of Dancing Explained. The first edition by Essex did not utilize the illustrated plates used in Rameau’s original text but rather replicated them nearly exactly, with translated captions. However, the human figures in the Essex translation were executed with greater artistry than Rameau’s simple figures, and the etchings were drawn with additional detail in the surface of the dance floor, including the suggestion of perspective and the dancer’s shadow on the floor surface, as well as shading on the dancer’s clothes (fig. 5).

Figure 5. A demonstration of the fifth foot position, in The Dancing Master (1728), John Essex’s translation of Le Maître à Danser, plate 12.

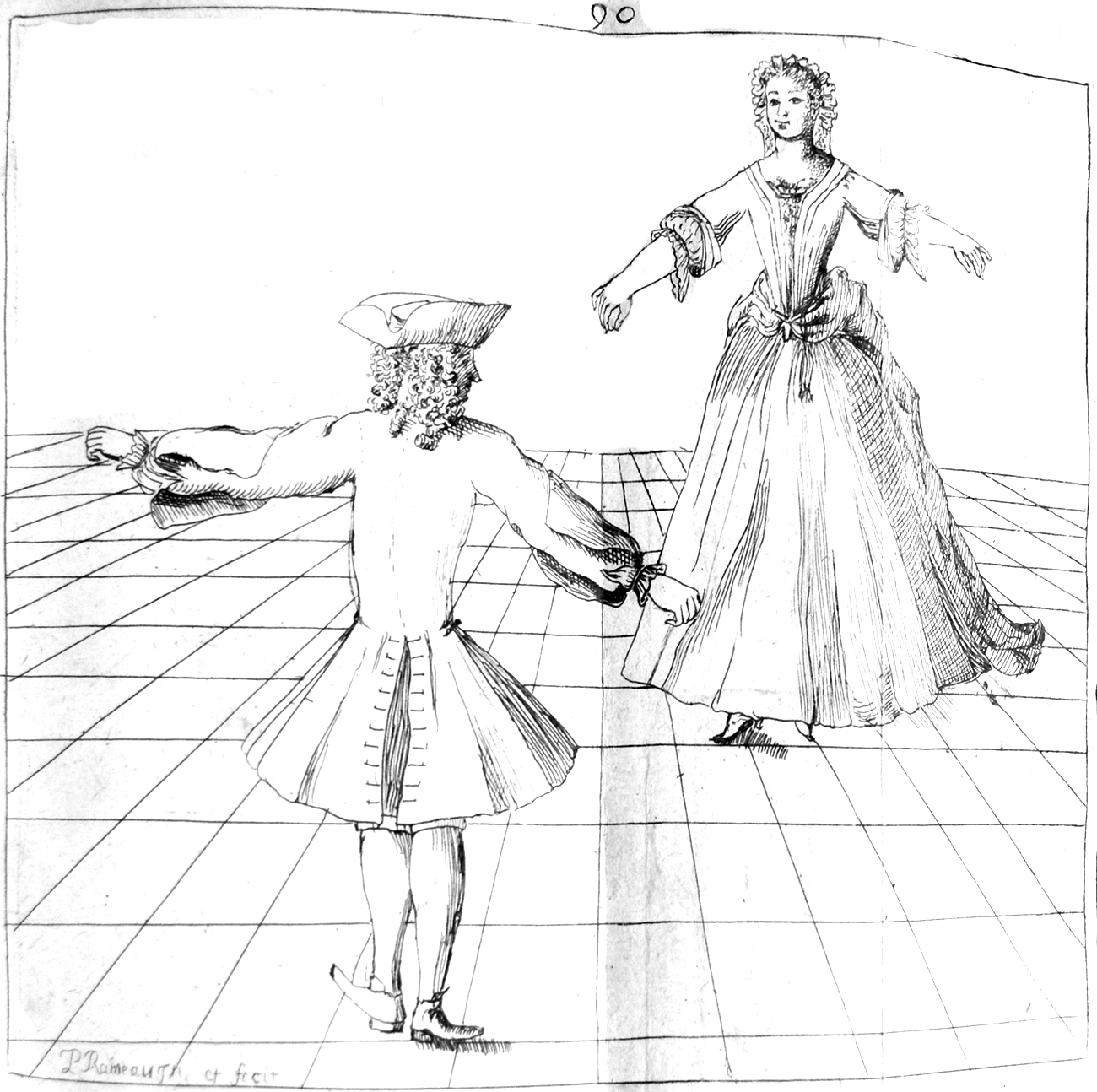

In Rameau’s original text, a folded plate of somewhat abstract illustration also suggests the use of perspective: this image utilizes a grid on the dance floor that angles toward a vanishing point, with a male and a female dancer mid-dance (see fig. 6). These simple suggestions of perspectival representation begin to reflect (or prefigure, depending on whose narrative one believes) the work of Kellom Tomlinson, whose innovative illustration style utilizes figurative, diagrammatic, and perspectival representation simultaneously to present a more complete picture of Baroque dance than is presented by any other dancing master of the day.

Figure 6. Oversized illustrated plate of male dancer and female dancer, from Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître à Danser (1725).

Tomlinson’s unique tome The Art of Dancing was published in 1735, though according to Tomlinson and sworn witnesses, his book was completed in 1724, one year prior to Rameau’s publication of Le Maître à Danser, not to mention four years before the first translation of Rameau by John Essex. The Art of Dancing is, simply stated, a manual for solo and partner dancing in a formal setting. Comprising 182 leaves of text and thirty-seven illustrated plates, the book represents Tomlinson’s major intellectual contribution to the written works of dance notation. The illustrated plates are divided into two books, the first of which addresses various dances and dance phrases for a man or a woman, and the second of which exclusively addresses the subject of the minuet, a highly important dance of the day. Nearly all of the illustrated plates are dedicated to a subscriber or one of Tomlinson’s former students; after spending eleven years raising funds for publication, Tomlinson likely had a number of people to whom he needed to express gratitude.

The Art of Dancing is Tomlinson’s best-known and most studied work, and it currently serves as a reference for scholars and performers of eighteenth-century dance styles. Tomlinson composed the notational portions of his work in Feuillet notation, but several important enhancements should be noted. Tomlinson’s notational innovation lies almost entirely in his conjoining of the dancing human figure with the path indications of Feuillet notation to present a simultaneous picture of the dancing figure, the dance floor, the steps of the dance, and the path of the dance’s movement. Tomlinson also includes bars of the relevant music, with the corresponding movement phrases indicated by number. On occasion Tomlinson also includes mirrored images of the steps for either the right foot or the left foot leading (fig. 7).

Figure 7. Musical score and dance notation of a portion of the saraband, in Kellom Tomlinson’s The Art of Dancing Explained (1735), book 1, plate 6. Note the mirrored notation for leading with the left foot or the right foot.

Like Rameau, Tomlinson employs illustrations of the human figure to show the foot and body positions of the dance, but unlike Rameau, whose figural representations primarily showed static positions, Tomlinson’s figures are meant to show a given moment in the performance of a dance, sometimes midmovement. An image such as book 1, plate 13 (fig. 8) illustrates a shift of weight from one foot to the other during the dance. In Tomlinson’s illustrated exposition of the minuet, we can glimpse something of the grace and formality of this dance (fig. 9).

Figure 8. Musical score and dance notation for the first movement of the chaconne, in Kellom Tomlinson’s The Art of Dancing Explained (1735), book 1, plate 13. In his illustrations of solo dance, Tomlinson regularly presents mirrored notation for leading with either side of the body.

Figure 9. The final illustrated plate depicting the music, dance notation, and dancing figures of the minuet in The Art of Dancing Explained (1735), book 2, plate 14. All fourteen illustrated plates of book 2 depict the minuet.

Tomlinson’s particular style of dance notation is remarkable due to its complexity and thoroughness. In her introduction to a recent reprint of a workbook by Tomlinson, Jennifer Shennan provides a contextual explanation of Tomlinson’s notation style:

Baroque dance notation features abstract step symbols placed on a stave which graphically represents the floor patterns of the dance; it is read in conjunction with a music stave on the same page. The notation thus operates two dimensionally, with the paper on which it is written representing the floor. In the illustrations for his books … Tomlinson took the artistic license of drawing actual dancers onto the page and notating stop symbols in a trail beneath their dancing feet. His illustrations are thus an ingenious combination of the horizontal and the vertical, so that we look both at, and down onto, the images at the same time. (Reference Tomlinson and Shennan1992, 5)

The illustrations in The Art of Dancing were created by a team of some of the finest engravers of the day, working under Tomlinson’s instruction. It can be presumed that Tomlinson would likely have made crude sketches of the desired images, perhaps adding or substituting verbal description of the particular postures to be depicted. The full roster of illustrators included George Bickham, Gerard Van der Gucht, George Vertue, and Henry Fletcher, who accounted for the better-known engravers, as well as R. W. Seale, J. Smith, and I. Clark. In addition to this, two plates (bk. 2, plate 1, and bk. 2, plate 12) were delineated by Arnold Vanhaecken and engraved by G. King. Subtle differences in engraving style are visible throughout, namely in the depiction of the dancers’ hands, altogether these stylistic differences are relatively easy to overlook when reading the images for movement instruction and content, rather than for traces of authorship.

The original cost of the book is stated by Tomlinson in the book itself, both in his preface and in the introductory plate to the first book of plates. Tomlinson notes the price of his book in comparison to Rameau’s book, which cost half as much and, Tomlinson asserts (Reference Tomlinson1735, 15), was correspondingly inferior. In the introductory plate to the plates correlating to book 1 of the printed portion of the book, Tomlinson notes: “The Price of the cuts belonging to the first and second Books without ye Printed Part, is Two Guineas, and those who are willing also to purchase the latter, viz. the Printed Part, may have it of the author … for Half a Guinea, pursuant to my Printed Proposals wherein I assured the Public, that the whole Work, except to Subscribers, should not be sold under Two Guineas and a Half” (125). The relatively high price of the book is likely due in large part to the expense of the artwork, the heavy paper stock used for the plates, and the overall quality of the work. As mentioned above, several of the engravers were among the recognized names of their day in the art of engraving; the expense incurred by Tomlinson to commission the production of the illustrated plates from these engravers might have been high. Beyond this, the cost of merely producing the textual portions of the book, or “the printed part,” to use Tomlinson’s words, could have been formidable to a dance instructor whose income was likely inconsistent and relied upon a form of patronage.

At a cost of two guineas, Tomlinson’s masterwork would have seen sales restricted only to the very wealthy, since the average income in Britain at this time was approximately thirteen guineas per year.Footnote 2 Like other printed books of this era, the binding of the printed pages would likely have been at the discretion of the purchaser, with the book sold as an unbound collation of gathered pages (i.e., in “signatures,” to use historic bibliography terms), accompanied by a stack of printed plates. In his introduction to each of the two sections of the printed plates Tomlinson reveals that his intentions for the illustrated plates were not necessarily to see them bound with “the printed part.” Tomlinson encourages the reader to consider that the engravings would serve as “proper Furniture for a Room or Closet, being of themselves an intire [sic] and independant [sic] Work, for if put in Frames with Glasses, they will […] be very agreable [sic] & instructive Furniture” (Reference Tomlinson1735, 125). Curiously, Tomlinson makes no specific suggestion to hang these images in a room where dancing or dance instruction would take place. If one regards the plates not as illustrations bound in a book but rather as independent artwork worthy of framing and display, perhaps the price of two guineas seems like a bargain.

Kellom Tomlinson was both a notator of his own dances and a firm proponent of inculcating dance literacy in the dancers he taught, most of whom were the children of English nobility and gentry. Most dancing masters of the time had professional scribes notate their compositions for publication, but Tomlinson was one of the few masters to prepare his own dancing notations. Tomlinson championed the cause of dance pupils learning to read dance notation or “characters” and expressed scorn for those who taught children to “dance without book” (17).

In the preface to The Art of Dancing, Tomlinson explains the relationship between his new work and the dance manuals and works in notation by Feuillet and others that preceded his book’s publication:

This Undertaking [i.e., The Art of Dancing] must needs have been attended with great Difficulty, because it was really the first of the Kind. For tho’ Monsieur Beauchamp lay’d the first Foundation, upon which Monsieur Feuillet built, (as some more ingenious Person may perhaps improve upon mine); yet the Works of both relate only to the Characters of Dancing; which, like the Notes of Music, can be only useful to Masters, and cannot be understood by any other without their particular Instructions. But the Piece which I here offer to the World will be of general Use to all, who either have learned, or are learning to dance: the Words describing the Manner in which the Steps are to be taken; and the Figures representing Persons as actually taking them; both which together will make the Learning more pleasant to the one, and serve as a continual Remembrancer to the other. (Reference Tomlinson1735, 17)

As Tomlinson states in his preface to The Art of Dancing, “The Figures in each Plate are designed only to shew the Postures proper in Dancing, but not to bear the least Resemblance to any Person to whom the Plate is inscribed; which it had been ridiculous to have attempted” (14). Tomlinson goes on to explain that gloves were deliberately omitted from the illustrations in order to best display the expressive gestures of the hands in the dances depicted, and he begs the forgiveness of the reader for any shortcomings: “The Faults, which may have happened in the Execution, either of the Printing, or Ingraving, will, I hope, be the more eaſily execuſed, if the Nicety of the Subject be considered, together with the Difficulty of the Performance, and the many Hands through which it has paſſed: eſpecially if it be remembered, that this is not only my firſt Attempt, but likewiſe the firſt that has been made of the Kind” (14). Tomlinson conveys his own heightened awareness of the originality of his method of notation in his caption text to plate 7: “The figures to ye Music above & to ye characters or steps of Dancing below shew, how they are connected or agree together; & ye Figures to ye Characters, which are some of them upright & others ye wrong End upwards, sideways, &c. shews to which part of ye Room ye Beginning of ye Steps is performed, & ye Steps or Characters are place upon ye Floor in a perspective Manner entirely new” (130). Throughout The Art of Dancing, Tomlinson repeatedly draws the reader’s attention to the originality of his illustrated notation style. This highlighting is done both through textual assertions as well as through an inscribed signature in each illustration: “K. Tomlinson [or K.T.], inv.”—that is, “K. Tomlinson, inventor.” While the addition of “inv.” in an engraving can mean simply the creator of an image, Tomlinson insists on a broader conceptual meaning. He refers to the concept of invention in his preface, noting “my invention” and expressing profound concern that any other dancing master should attempt to claim credit for his innovation in depiction style (15). Beyond this, Tomlinson devotes nearly one-third of the preface to The Art of Dancing to discussing the similarities between his work and that of Rameau. Tomlinson notes in his preface that his The Art of Dancing was completed by 1724, but financial hindrances did not allow publication until eleven years later. This unfortunate timeline appears to have vexed Tomlinson not only for the obvious financial reasons, but also because of the attention and privilege accorded to ensuing works on dance that came to publication while his ostensibly completed work lay fallow. As historian Wendy Hilton describes, “Kellom Tomlinson suffered the agonizing experience of writing a book and, before it could be printed, witnessing the publication of another similar in content. The Art of Dancing was completed in 1724, but it was not until 1735 that a total of one hundred and sixty-nine subscribers had donated sufficient funds to support its publication in London.” While this unfortunate publishing timeline might bring to mind the publication controversy surrounding the development of calculus independently by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, neither Tomlinson nor Rameau accused the other of plagiarism.

Thoroughly unraveling the connection between Pierre Rameau’s 1725 dancing treatise and Tomlinson’s 1735 masterwork may not be feasible, but several pieces of information are quite clear. Beyond the similarities of title, the illustration styles of Tomlinson and Rameau are highly similar. Although nearly identical in content and composition, the engravings in Rameau’s book are technically inferior to Tomlinson’s engravings, with awkwardly proportioned human forms, clothing that appears unaffected by gravity, and feet and legs that appear to bear no weight. Tomlinson’s illustrations show well-proportioned dancers whose clothing and bodies appear affected by gravity in a natural manner. In both works, the similar use of perspectival viewpoint and display of the dance floor is striking; however, this viewpoint should be regarded as common to its historic moment, since numerous other examples exist of early eighteenth-century prints depicting dance that bear similar composition and staging. Aside from any technical superiority, one notable difference between Rameau’s illustrations and Tomlinson’s lies precisely in what Tomlinson declares as his great innovation: the presentation of dancers, the dance floor with notated steps trailing after the dancers’ feet, and the musical score for the dance. Whether Rameau’s work was truly the original explanation of dance that Tomlinson improved upon, or whether Rameau was a lesser imitation of Tomlinson’s long-completed, slowly published work, it is clear that Tomlinson’s work is a greater achievement of visual art and representational innovation.

Tomlinson’s depiction method was not only original and distinctive at its moment of production, but ultimately it proved to be wholly unique over time. While even Feuillet’s early notation scores linked dance steps with musical scores, no other ensuing dance notation method has embraced the same approach as Tomlinson in dance notation depiction that displays a melding of the technical, the representational, and the illustrative in a simultaneous image. The notational style presented by Tomlinson in The Art of Dancing is more elegant than Rameau’s, though less exhaustive in the roster of movements; it is more illustrative, though less thorough. The question arises as to whether Tomlinson’s method was, perhaps, irreproducible, or whether, with the waning of the Baroque fashion of dance, notation was no longer suitable. As Ann Hutchinson Guest notes, “Though the [Feuillet] system served the 18th century so well, it offers nothing as a practical system for dance today. … The system was very much a product of, and suited to, the dance of its period” (Reference Guest1989, 21). As Guest indicates, a representational system and the thing represented bear upon each other a strong influence.

While analogies between music and architecture are abundant in scholarship and popular architectural dialogue, analogies between dance and architecture are frequently more appropriate, and this is particularly true in regard to dance notation. Notation was to dance what printing was to architecture: a means to broadcast the original works of an author to a wide audience, to establish the prominence and name recognition of the dancing master or the master builder, and to engender the professionalization of the field itself. The dancing masters of the eighteenth century contributed to discussions about the influence of representation in the field of dance; similar discussions are perennial in the field of architecture. In the case of dance, the spatial forms are fleeting, whereas in architecture the forms are durable. Both practices have spurred discussions within their respective fields about the implications of the mutually influential relationship between representation and the thing represented. As architectural historian and theorist Robin Evans states in his discussions of architectural projection, in architecture there is an inevitable concordance of building and representation: “In architectural drawings the projectors are not only perpendicular to the sheet of paper but also perpendicular to the major surfaces of the building drawn on it. Buildings are often rectangular, so aligning their surfaces with the surface of the drawing seems a sensible thing to do; yet this convention of imaginative vision also helps keep them that way. Whether it does so like some sort of butter paddle or like some sort of rolling pin—whether, in other words, it makes buildings into blocks or sheets—it is a powerful, conservative, forming agency” (Blau et al. Reference Blau, Kaufman and Evans1989, 25). While rectilinearity clearly was not the issue in question for the dancing masters of the eighteenth century, the issue of constraints provided an important point for debate. Some dancing masters perceived a risk of fixity in choreography and composition when dances and specific movements were put to paper. In dance as in architecture, the selected tool or method of representation circumscribes the possibilities not only of depiction, but of form or action as well.

Irmgard Bartenieff (Reference Bartenieff1963, 3–5) describes Jean-Georges Noverre, a French dancing master of the mid- to late eighteenth century who feared that the process of notating dances would result in a general stultifying effect within the field, whereby the only dances performed would be those that previously had been recorded, with movements limited to those that had found shorthand notation in books. If Bartenieff’s assessment of Noverre’s opinions is accurate, we can presume that as the grandfather of modern ballet, Noverre may have helped to marginalize the practice of dance notation. Presumably his opinions on the topic of notation would have permeated his teaching and borne an influence on later generations of dancers and dance instructors. Beyond any influence on the field wielded by Noverre’s antipathy toward notation, it was Noverre’s choreographic innovation of ballet d’action itself which helped to end the practice of Baroque dance notation. As a movement style, ballet d’action was marked by an increased use of gestural and emotive movements, in distinction to the precise and highly formalized movements in Baroque social and theater dance. To be more specific, the gestural and emotive movements of ballet d’action were situated in and performed by the arms and upper body, as opposed to the footwork-dominant dance of the Baroque. This shift in bodily emphasis would have presented a significant problem for the capacities of the dominant dance notation of the time. As Linda Tomko states (Reference Tomko1999, 3), “Beauchamp-Feuillet notation was absolutely incapable of indicating arm gestures for ballroom and theatre choreographies alike.” Tomko goes on to describe that “in practice, arm motions were almost never specified.” As mentioned above, Feuillet hardly addressed the movement of the arms, and Rameau only later attempted to address the upper body. Tomlinson’s addressing of the arms was done only through his illustrated figures, and his use of Feuillet’s footwork notation precludes an effective incorporation of arm movements in notation. As Mark Franko (Reference Franko2011, 324) suggests, Baroque dance notation contributed to something of a closed loop in choreography: “These spatial relationships—the relations of the dance floor and the danced patterns upon it to notational script and the page—underlie the sense that baroque dance existed largely in relation to the conditions of possibility of its own notation.”

While a limited system of notation such as that developed by Feuillet and expanded upon by Rameau and Tomlinson may impose particular constraints that ultimately create the disuse of such a system, the benefits of dance notation were numerous, and chief among them was posterity. The advantages gained by dance notation are described contemporaneously by Soame Jenyns in his 1729 poem The Art of Dancing:

Ultimately Baroque dance notation fell into disuse entirely, but the great age of Baroque dance documentation exerted a lasting effect on the field of European ballet. The standardization of the foot positions, jumps, and basic movements in the Baroque era contributed to a durable, recognizable ballet vocabulary that has carried through to the present day. Dance notation of the early eighteenth century helped to transform an art form formerly “unfix’d and free,” taught by numerous masters in a range of stylistic and technical variations, into an art that relies on a specific fundamental vocabulary of technical movement.

Every technical drawing or representation presents a proposition about the world therein depicted. Even a superficially neutral drawing contains implicit instructions for viewing and suggests methods for interpretation. The privileging of a viewpoint, for example, or the choice between axonometric or perspectival, conveys cultural priorities and personal sensibilities. In the humanistic Renaissance, the use of perspective flourished; the eye of the viewer was the operative viewpoint. In Tomlinson’s work, one can see the privileging of order and grace, and of dance literacy and proficiency. Tomlinson’s illustration style truly is The Art of Dancing’s most remarkable feature, a unique representational method that continues to captivate modern readers much as it did nearly three hundred years ago.