Issues concerning agriculture, rural areas, and the rural population are of utmost significance in China. Given their status as the dominant group in Chinese society and their pivotal role in the agricultural sector, farmers who are integral to the recently proposed “rural revitalization” strategy merit primary focus. Since the advent of feudalism, farmers have traditionally been perceived as the most marginalized social group, occupying the lowest position in the hierarchical structure of society. For an extended period, this particular group has been consistently identified as being vulnerable and subjected to stigmatization by the mass media, enduring entrenched discrimination and prejudice. The media have the potential to challenge prevailing notions regarding poverty (Carroll and Ratner Reference Carroll1999). Media images have a direct bearing on the public perception of a given group (Gamson et al. Reference Gamson1992). To advance the agenda of rural revitalization and foster agricultural development, the mass media must assume the responsibility of rectifying the biased and one-dimensional perception of farmers, thereby enhancing their social standing within Chinese society. Consequently, the images of farmers are highly worthy of academic attention. Nevertheless, a search undertaken in September 2023 using the term “media image” on the search engine demonstrated that significant scholarly attention has been devoted to the media images of specific groups, such as nurses (Cao et al. Reference Cao2022), older individuals (Li Reference Li2021), CEOs (Gates et al. Reference Gates2009), and women and men (Farquhar and Wasylkiw Reference Farquhar2007; Harper and Tiggemann Reference Harper2008). Media images of farmers have received rather scant attention. Existing scholarly investigations primarily focus on the field of communication and media studies. For instance, Hu (Reference Hu2022) and Huang (Reference Huang2023) conducted research on farmers’ images in the verbal coverage of People’s Daily and Farmers’ Daily. Based on mirror image theory and framing theory, these analyses focused on aspects such as farmers’ occupations, behaviors, and moralities. A thorough review of previous studies on farmers’ images sheds light on several noteworthyconstraints. In terms of research discipline, contemporary research focuses predominantly on media studies. Interdisciplinary studies involving linguistics and semiotics are limited in availability. As for research materials, current studies are primarily restricted to verbal news texts. The potential significance of nonverbal modes in shaping the perception of farmers’ identities is prone to being disregarded. As far as the research methodology is concerned, the qualitative content analysis approach plays a dominant role, outnumbering quantitative empirical studies.

In today’s multimedia age, press discourses are often supplemented, or even surpassed, by information communicated through nonlinguistic semiotic resources. The age-old saying that a picture is worth a thousand words justifies the necessity to expand contemporary research into multimodal discourses. “Modality” refers to a “means of making meaning”: “The term ‘multimodality’ was used to emphasize that meaning is constructed using different semiotic resources” (Jewitt et al. Reference Jewitt2016, 2). From a social semiotics perspective, signs exist in all modes. It is necessary to consider all modes in meaning production. Meaning making does not occur in isolation but rather arises through the coordination of modalities and social interactions. News cartoons, which utilize various semiotic resources such as images, layouts, and language, are typical multimodal discourses. The interaction among different modalities, as well as between the information conveyed by signs in cartoons and the background knowledge of viewers, leads to meaning-complex.Footnote 1 This is why cartoons often have more profound implications than what is explicitly stated. A metaphor is a sign function that can be expressed through various sign vehicles, resulting in a multimodal metaphor. Derived from semiotic interactions, metaphors and metonymies are common maneuvers exploited by cartoonists to convey rich meanings, enhance perceptual comprehension, and gain wider public approval (Morrison Reference Morrison1992; Edwards Reference Edwards1997; Templin Reference Templin1999). According to O’Halloran (Reference O’Halloran2003, 357), metaphors occur intersemiotically when a functional element is reconstructed using a different semiotic code. With this reconstrual, we observe a semantic shift or transference of meaning from one semiotic medium, such as visual, to another, such as linguistic. For example, the juxtaposition of the image stage with the word world implies the metaphor the world is a stage. In a metaphor, the “incongruity” between a signifier and a signified functions as an effective stimulus, inviting viewers to draw on their collateral experiences and observations to provide additional information, make inferences, and reach correct interpretations. This semiotic process makes full use of viewers’ subjective initiative and directs their attention toward specific aspects. Semiotic systems offer a wide range of choices for people to make meaning. The ability to choose endows them with the power to manipulate signs to affect and even alter meanings. In social semiotics, the selection and utilization of visual elements and features in communication not only represent the world but constitute it. The overuse of particular semiotic choices can serve as representational strategies to implicitly convey various forms of identities. Therefore, news cartoons that are rich in metaphorical and metonymical expressions are regarded as powerful instruments for shaping images and influencing public opinion. “Cartoonists often fall back on metaphorical expressions and stereotypes as a means of simplifying complex events and images, often portraying them in a negative light” (El Refaie Reference El Refaie2009, 176). Owing to their evaluative and communicative functions, metaphors employing certain semiotic resources in news cartoons often necessitate an additional explanation to discern the underlying critical stance (Schilperoord and Maes Reference Schilperoord2009).

Based on a compiled corpus comprising 48 farmer-themed cartoons selected from the China News Cartoon Network, this study attempts to arrive at a better understanding of which, how, and why specific metaphors and metonymies are used in constructing farmers’ media images by marrying insights from cognitive linguistics and social semiotics to those of media studies. By taking the multimodal critical metaphor/metonymy analysis approach, this research delves into the implicit attitudes, power dynamics, and social underpinnings embedded in the visual representations of farmers. Theoretically, this study offers a novel research perspective and interdisciplinary theoretical support for the advancement of farmers’ media representations. Practically, the research helps identify the deficiencies in the media’s efforts to shape images and come up with customized solutions. By doing so, this research provides practical guidance to the mainstream media, enabling them to fulfill a more competent role in acquainting the public with an authentic and deeper understanding of farmers.

Theoretical Framework

In this article, we go through some theoretical concepts that underpin the approach we take in the analysis that follows.

Multimodal Metaphor and Metonymy

Metaphors and metonymies have traditionally been regarded as figurative devices utilized in rhetorical discourse. It was only after the milestone publications of Andrew Ortony’s edited volume Metaphor and Thought (Reference Ortony1979) as well as Lakoff and Johnson’s seminal monograph Metaphors We Live By (Reference Lakoff1980) that the incorporation of metaphors into cognitive linguistics took place. With the emergence of the “conceptual turn,” metaphors underwent a significant transformation, shifting from being primarily a verbal trope to being understood as a cognitive conception. Since then, it has been widely accepted that metaphors are potent cognitive instruments that fundamentally structure our thinking, understanding, and conceptualization. This cognitive paradigm shift gave rise to the conceptual metaphor theory (CMT). Conceptual metaphor can be understood as “comprehending and experiencing one conceptual domain in terms of another domain, achieved through a mapping from the source domain to the target” (Lakoff and Johnson Reference Lakoff1980, 5). Conceptual metaphors often adopt the verbalization of noun a is noun b (e.g., argument is war). If the fundamental principle of CMT that human cognition is inherently metaphorical holds true, then the investigation of metaphor should not be confined solely to one dimension where language is only its external manifestation. Based on this assertion, Forceville (Reference Forceville2006) argued that metaphors can be manifested multimodally as well as verbally. This observation has led to the concept of “multimodal metaphor.” In the narrow sense, multimodal metaphors are metaphors “whose target and source domains are primarily or exclusively represented in two distinct modes or modalities” (384). However, as Forceville admitted (385), the majority of targets and/or sources in multimodal metaphors are cued in more than one mode simultaneously. Multimodal metaphors, in a broad sense, are metaphors “where the target and source are represented exclusively, predominantly, or partially in different modes” (El Refaie Reference El Refaie2009, 191). To emphasize the dynamic nature of multimodal metaphor, Forceville and Urios-Aparisi (Reference Forceville2009, 11) broadened the paradigmatic formula to a-ing is b-ing. The study of metaphor is inseparable from metonymy. Metonymy is considered a more fundamental cognitive phenomenon than metaphor. Now the conceptual nature of metonymy has been widely recognized. An increasing number of cognitive linguists have made significant contributions to testify to its indispensable role in motivating target and source domains for metaphor, as well as highlighting its mappings.Footnote 2 Metonymy is the substitution of one thing for another within the same idealized cognitive model (ICM), which can be interpreted as x stands for y.

Metaphor has traditionally relied on the notions of “similarity” between different cognitive domains, whereas metonymy is based on a relation of “contiguity” (Jakobson Reference Jakobson1971). Metonymy, like metaphor, has experienced a “multimodal turn” and has been expanded to multimodal metonymy. Forceville and Urios-Aparisi (Reference Forceville2009, 12) have emphasized the necessity for every property or feature to establish a metonymic association with the source before its mapping onto the target. The phenomenon of metaphor and metonymy interacting with each other is referred to as “metaphthonymy,” according to Goossen (Reference Goossens1990).

Multimodal Critical Metaphor/Metonymy Analysis

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is dedicated to examining the interplay between linguistic structure and social structure. The objective of this analysis is to investigate the linguistic characteristics of discourse to uncover the concealed inequalities, power dynamics, and ideologies that exist in language, both explicitly and implicitly (Fairclough Reference Fairclough[1989] 2001; Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk1993).

In essence, metaphors serve as a valuable tool for enhancing our comprehension of a particular concept by drawing parallels to another. This is achieved by associating the attributes of the source domain with those of the target domain, resulting in the highlighting of certain aspects while backgrounding and suppressing others. The process of mapping has the potential to exert substantial influence and exercise control over our understanding of a specific object or concept. Metaphor is such a mighty cognitive tool that when we accept a metaphor, we embrace the conceptual framing imposed on us and internalize the constructed “reality” that the metaphor presents. “Certain types of meanings, identities, practices, and ideas are strategically constructed to present themselves as natural and commonly accepted” (Mayr and Machin Reference Mayr2012, 3). By modifying the metaphorical framework, it becomes feasible to alter our cognitive processes and emotional responses toward objects and individuals. Given the profound influence that metaphors exert in shaping and influencing meanings, understandings, and opinions, it is necessary to adopt a critical approach when interpreting them. This approach allows for a more profound understanding of the beliefs, motivations, intentions, and attitudes that underlie the selection of one metaphor over another. As stated by Fairclough (Reference Fairclough1995, 94), metaphors possess “latent ideological implications as they can shape and construct the perceived reality of the world, influencing our attitudes and beliefs.” Therefore, the inclusion of metaphor analysis is essential to critical discourse analysis. In his groundbreaking work Corpus Approaches to Critical Metaphor Analysis, Charteris-Black (Reference Charteris-Black2004) introduced the innovative method of critical metaphor analysis (CMA), which was developed to understand the function and impact of metaphors in discourse. The cognitive process of mapping in metonymy entails mental highlighting or activation of one (sub)domain over another (Barcelona Reference Barcelona2002). The primary purpose of this function is to ascertain the identity of an object based on a prominent feature present within it. A metonymy can have a strong emotional or evaluative connection to its source. The operational mechanism of highlighting and evaluating serves specific objectives. In light of this, it can be argued that metonymy should be considered as an inherent element of CMA.

Language serves as a medium for social construction (Hodge and Kress Reference Hodge1988), although it is not the exclusive means. Nonverbal modes also have a significant impact on the construction and representation of social reality, as they possess the potential to navigate and convey ideological messages. Ideologies are inherently present wherever signs are observed. In the late 1980s and 1990s, there was a growing interest among linguists to observe the attitudes, ideologies, and power dynamics conveyed through nonverbal semiotic resources. Against this background, CDA underwent a transition toward a multimodal dimension. In their far-reaching monograph How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis, Mayr and Machin (Reference Mayr2012) put forth the argument that multimodal critical discourse analysis (MCDA) plays a crucial role in challenging and dismantling commonly accepted assumptions conveyed through various modes of communication. Compared with their verbal counterparts, “non-verbal multimodal metaphors are more effective in highlighting specific aspects of conceptual metaphors” (Forceville and Urios-Aparisi Reference Forceville2009, 13). It is justifiable to integrate multimodal metaphor, multimodal metonymy, CMA, and MCDA into one framework. The ideological dimension in the study of multimodal metaphor/metonymy has introduced a new analytical approach known as multimodal critical metaphor/metonymy analysis (MCMA). Based on Fairclough’s three-dimensional analytical framework of CDA, the process of MCMA involves three steps: metaphor/metonymy identification, interpretation, and explanation (Charteris-Black Reference Charteris-Black2004).

Research Methodology

This is a multimodal corpus-based empirical study in which a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods will be employed to approach comprehensive and convincing conclusions.

Research Questions

What we try to do in this study is threefold: First, what are the salient internal and external semiotic resources employed to indicate images of farmers in these cartoons? What types of multimodal metaphors and metonymies are constructed and what are the features that are mapped from the source to the target? What is explicitly said and what is implicitly meant by these tropes? Second, what kinds of farmers’ images are portrayed through the utilization of multimodal metaphors, metonymies, and their interactions? What evaluative attitudes are implicitly reflected: negative, neutral, or positive? Third, what socioeconomic factors can be found that underlie these images? What shortcomings can be identified in the current endeavor of image construction and what recommendations can be provided for future improvement?

Data Collection

To ensure the credibility and inclusivity of the study, all the cartoons included in this research were sourced from the China News Cartoon Network (http://cartoon.chinadaily.com.cn/index.shtml). This website holds the distinction of being the foremost and highly regarded platform for cartoons in China. A search was conducted using the term 农民 ‘farmer’, resulting in a total of 78 cartoons obtained from the website. The search spanned a period of nearly five years, from January 2019 to September 2023. Subsequently, a more in-depth analysis and evaluation of these cartoons was conducted by employing two-dimensional selection criteria. To fulfill the criteria, the selected cartoons must adhere to two specific requirements. In terms of content, the cartoons must contain images of farmers. In terms of cognitive mechanisms, the cartoons should incorporate multimodal metaphors and/or metonymies. Under the guidance of their broad definitions, the identification of a multimodal metaphor/metonymy in a cartoon was facilitated by the implementation of three criteria recommended by Forceville (Reference Forceville2008, 460):

-

1. Considering the context in which they occur, the two phenomena can be classified into different domains.

-

2. The two phenomena can be slotted as target and source, respectively, and can be represented in an a is b or a-ing is b-ing format. This format compels or encourages the recipient to map one or more features, connotations, or affordances from the source to the target.

-

3. The two phenomena are cued in more than one sign system, sensory mode, or both.

Similarly, for a metonymy to be counted as a multimodal metonymy, three criteria must be met:

-

1. Given the context they appear, the two elements belong to the same experiential domain.

-

2. The two phenomena can be slotted as the target and source, respectively, and can be represented in an x stands for y format. The source domain facilitates cognitive accessibility to the target by highlighting one or more features within the target.

-

3. The two phenomena are cued in more than one sign system, sensory mode, or both.

To minimize subjectivity and ensure the accurate identification of metaphors and metonymies, a method of three-person back-to-back analysis was employed. The three participants are experienced college educators who specialize in cognitive linguistics and have spent years researching multimodal metaphors and metonymies. After conducting independent coding, our team engaged in regular discussions to address any discrepancies or conflicts that arose. Finally, a consensus was reached on a total of 48 cartoons.

Data Processing

Based on the self-built corpus, we carried out a three-dimensional analytical framework of CMA: identification, interpretation, and explanation (Charteris-Black Reference Charteris-Black2004). Metaphor/metonymy identification is concerned with description and classification in which the types of source domains were identified and classified into different categories through qualitative analysis. The quantitative method is utilized to compute the frequencies of their usage, employing the formula Resonance = Σtype × Σtoken (Charteris-Black Reference Charteris-Black2004, 90). Types are separate visual forms of source domains while tokens are the number of times each form occurs. Resonance is the sum of the tokens multiplied by the sum of the types of metaphors/metonymies. The higher the resonance value is, the more frequently the rhetorical device is used. Metaphor/metonymy interpretation involves establishing a relationship between tropes and the cognitive and pragmatic factors that determine them. In this phase, the interpretation of representative multimodal metaphors and metonymies is provided, focusing on their conceptual bases, operational mechanisms, and image construction processes. At the stage of explanation, the implicitly expressed viewpoints and the social agencies involved in their production are to be clarified.

Findings

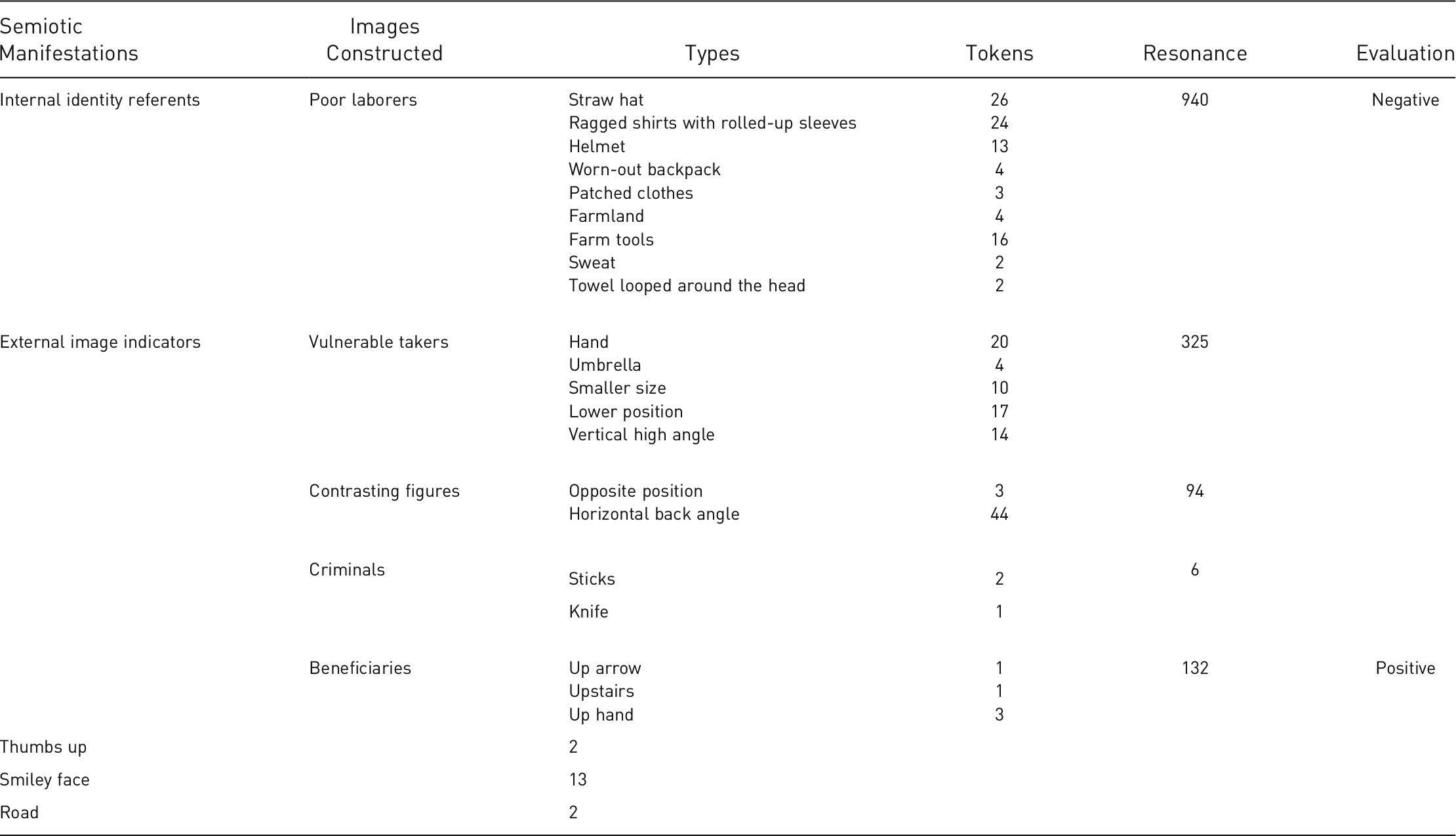

Specific semiotic choices can convey meaning and signify particular types of identities. In the identification phase, the visual source domains in metaphors and metonymies are initially categorized into two groups: internal semiotic manifestations serving as identity referents, and external semiotic manifestations functioning as image indicators. The former refers to visual symbols primarily found in the physical appearances of farmers, which are utilized to differentiate their identities as farmers. The latter refers to nonverbal signs that are external to the farmers’ physical appearance and are not directly associated with their identities as farmers. However, these signs can, to a certain extent, mirror their public perception. Based on an elaborate exploration of the corpus, table 1 displays the types and tokens of the source domains along with their resonance. Resorting to these signs and their evocative exploitation of meanings in viewers, the metaphors and metonymies in these cartoons mainly construct five distinct stereotypical representations of farmers, which will be thoroughly analyzed and interpreted in subsequent sections.

Table 1. Internal and External Semiotic Manifestations of Farmers’ Images

Farmers Are Economically Disadvantaged Individuals Involved in Manual Labor

As for the internal semiotic manifestations serving as identity referents, a total of nine visual source domains can be identified, as illustrated in table 1. Cartoonists employ these symbols to represent the identities of farmers and frequently complement them with linguistic modes. This kind of referential shift phenomenon can be referred to as multimodal metonymies. Generally speaking, metonymy can be classified into two broad categories. The first category is the whole ICM and its parts, which include thing-and-part ICM, scale ICM, constitution ICM, event ICM, category-and-member ICM, category-and-property ICM, and reduction ICM. The second category is the parts of an ICM, which consist of action ICM, perception ICM, causation ICM, production ICM, control ICM, possession ICM, containment ICM, location ICM, sign and reference ICMs, and modification ICM (Radden and Kövecses Reference Radden1999). Four identifiable metonymic types can be observed in identity referents. The first is the constitution ICM, and precisely the metonymy a person’s clothing stands for identity. In China, it is common to observe manual laborers wearing straw hats and ragged shirts with rolled-up sleeves, with towels wrapped around their heads while they work outdoors. These attire choices serve the purpose of shielding them from the sun and absorbing sweat. In cartoons, farmers are often depicted wearing this cheap attire to highlight their engagement in manual labor. Helmets and worn-out backpacks symbolize the identity of “migrant workers,” a term used to describe agricultural laborers who migrate to urban areas in search of employment opportunities. In figure 1, the source of the metonymy helmet/tatty backpack stands for migrant worker is represented in visual mode, the target in the written mode 农民工 ‘migrant worker’. Rural migrant workers are characterized by their involvement in low-status manual and unclean occupations, such as construction workers, janitors, and childcare providers. In China, there exists a prevalent bias against this group, especially among urban residents. In action ICM, we have metonymy object used for user. Hoes and tractors are frequently utilized as agricultural implements. They help anchor the users as farmers which are usually supplemented by the verbal message 农民 ‘farmers’. workplace stands for worker of location ICM is exemplified by the cartoons utilizing the imagery of farmlands to signify farmers. Causation ICM—to be specific, the effect stands for cause metonymies—is illustrated by two source domains: patched clothes and sweat. Patched clothing is commonly associated with poverty and is frequently used in the media as a synonym for poverty. Physical exertion tends to induce profuse perspiration. It is common to observe farmers portrayed in attire adorned with patches and drenched in perspiration. Metonymy can be understood as a form of domain highlighting, as proposed by Croft (Reference Croft1993). Cameron (Reference Cameron2007) has shown that when we talk about certain subjects, they may be dominated by reference to one particular source domain. What these source domains have in common is that they refer to the poor manual worker. Consequently, metonymic mappings serve to highlight and project the characteristics associated with being a poor manual laborer onto farmers, thereby implying the overarching “social role metaphor” that farmers are individuals who belong to the impoverished class and engage in manual labor.

Figure 1. “‘Gift Packages’ for Migrant Workers to Return to Work” by Dan Ni, published on February 27, 2020.

The communicator possesses a variety of options, both in verbal and visual forms, to determine their preferred method of representing individuals and groups. In CDA, this realm of semiotic choices is commonly known as “representational strategies” (Fowler Reference Fowler1991; Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk1993; Fairclough Reference Fairclough2003). These choices “allow us to place people in the social world and to highlight certain aspects of identity we wish to draw attention to or omit” (Mayr and Machin Reference Mayr2012, 77). Utilizing metonymic representational strategies that employ semiotic choices associated with extreme poverty and manual labor, cartoonists stereotypically portray farmers as economically disadvantaged laborers, which further reinforces negative and biased perceptions of farmers.

Farmers Are Powerless Takers with Low Status Who Need Help and Protection

Concerning the external semiotic manifestations functioning as image indicators, the most salient symbol observed is the “hand” which appears with a frequency of 20 times (see figs. 1 and 2). In psychology, the perception of wholeness is referred to as “gestalt.” In organizing incomplete information, individuals often adhere to the principle of continuation and the principle of closure. When presented with an incomplete hand, the human brain tends to instinctively extrapolate and fill in the missing parts to perceive it as a complete body. This holistic visual perception activates the thing-and-part ICM and results in a double metonymy: hand stands for body stands for person. In cartoons, the hands stretch out to make a gesture of giving, lifting, or warning. In action ICM, action stands for agent. The interaction between the thing-and-part ICM and action ICM brings about the “multimodal metonymic chain,” which helps us get to the final metonymy hand stands for giver/helper. The target of this metonymy acts as the source domain in metaphorical mapping. The Chinese characters embedded in the hands, such as “various levels of governments,” “Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs,” “local enterprises,” and “Migrant Workers’ Wage Guarantee Provision,” help anchor the target of the metaphor to be government, enterprise, or regulation. Once the target and source of a metaphor have been identified, the reader is encouraged to map the characteristics of a typical giver or helper onto the government, enterprise, or regulation. Through the interaction between metonymy and metaphor, a cross-modal metaphor government/enterprise/regulation is giver/helper can be inferred. This metaphor establishes a contrasting relationship between external helpers or givers and the farmers, as evidenced by the actions of the farmers depicted in the cartoons. When provided with something, individuals often extend their arms in a gesture of acceptance, constructing the metonymy opening arms stand for acceptance. By integrating the giver/helper metaphor and the acceptance metonymy, it is possible to elucidate the inherent “give-accept” relationship and establish the “social role metaphor”: farmers are welfare recipients who are reliant on receiving alms. They are the takers who need assistance. Welfare recipients are often subjected to substantial levels of prejudice and stereotyping within modern society (Wilthorn Reference Wilthorn1996). In their study, Fiske et al. (Reference Fiske1999) discovered that among the 17 stereotyped groups examined, welfare recipients were the sole group that respondents expressed both dislike and disrespect toward. The hand metaphor specifically highlights the dependent and vulnerable aspects of farmers. Perceiving farmers as recipients and takers will inevitably perpetuate discrimination and alienation.

Figure 2. “Fighting Wage Arrears with Law” by Luo Qi, published on January 2, 2020

In addition to the hand metaphor, another metaphor that can be identified is the umbrella metaphor (see fig. 3). The source domain is manifested in visual mode while the target is rendered linguistically through the Chinese characters on the umbrella: bottom-line safeguard mechanism, legal guarantee, and poverty alleviation. The cross-modal mapping from the source domain to the target domain leads to the metaphor guarantee/mechanism/poverty relief is an umbrella for farmers. In various day-to-day scenarios, individuals commonly use umbrellas as a means of safeguarding themselves against precipitation and sunlight exposure. In the umbrella metaphor, this protective feature is mapped onto the mechanism, guarantee, or measures taken by the government. While publicizing the benefiting policies, these cartoons subconsciously foreground farmers as a vulnerable group in need of “protection.”

Figure 3. “Health Security” by Luo Qi, published on November 17, 2020

A detailed observation of the hand and umbrella cartoons reveals the presence of a unique form of multimodal metaphor known as the orientational metaphor, which imparts a spatial orientation to a concept. Orientational metaphors arise when spatial concepts, such as up and down, near and far, center and periphery, and so on, are employed to organize another conceptual system, such as relations, emotions, status, and so on. Multimodal discourses offer the advantage of utilizing spatial layout to visually represent orientational metaphors, as opposed to verbal texts that are constrained by linear arrangement. “The layout can aid in expressing a metaphor” (Koller Reference Koller2009, 60). From the perspective of CMT, viewing arrangements to convey orientational metaphors serve multiple purposes, including emphasizing significance, signifying social status, visualizing social distance, and expressing power dynamics. Lakoff and Johnson (Reference Lakoff1980, 15) identified the most prevalent conventionalized orientational metaphors are good is up/bad is down, having control is up/being subject to control is down, and important is central/unimportant is marginal. Given that our physical and cultural experience of the up-down orientation also drops a hint about power differentials, it has become customary to associate power with an upward direction and powerlessness with a downward direction, namely, powerful is up/powerless is down. Status is closely related to social and physical power. Under normal conditions, powerful individuals who possess high social status tend to occupy an upper position. The metaphor high status is up/low status is down is evident in this context. These orientational metaphors are mainly contextual (Forceville Reference Forceville1996). The mapping of basic experience from the spatial domain onto abstract concepts is highly based on viewers’ physical experiences and cultural backgrounds. The source domains are visually cued, while the target domains remain invisible. The inferences need to be inferred based on the given context. In numerous instances, farmers are positioned below the upper hands and under the protection of umbrellas, symbolizing their lack of power and their lower status as a vulnerable group who are denied equal standing. Apart from the up/down metaphors, the utilization of size metaphors is also very common in cartoons. It should be noted that the size of an object not only indicates its salience but also connotes importance and power (Goatly Reference Goatly2007; El Refaie Reference El Refaie2009). In multimodal metaphor, the physical size of an object is mapped onto the target to imply its degree of power. Accordingly, importance/power is large size. In comparison with the larger hand, the farmer is relatively smaller in size, inducing a sense of vulnerability. Their equal importance is strategically downplayed.

Under the theory of visual grammar (Kress and van Leeuwen Reference Kress1996), special attention should be paid to the representational, interactive, and compositional meanings when analyzing multimodal discourses. Feng and O’Halloran (Reference Feng2013) proposed that the meanings within visual grammar exhibit a significant potential for metaphorical expression. The concept of “interactive meaning” encompasses the dynamic interplay between image creators, participants, and viewers. It contains contact, social distance, attitude, and modality. The first three elements are realized through gaze, shot distance, and camera angle, respectively. The correlation between camera angle and interactive meaning can be conceptualized as a metaphorical mapping between the source domain and the target domain. This mapping is established through “correlations that are derived from our fundamental experiences of the world” (329). Feng and O’Halloran accordingly came up with the metaphor image-viewer relation is camera position (329–30), which includes three subtypes: social distance is shot distance, power relation is vertical angle, and involvement is horizontal angle. The vertical angle metaphor can be further classified into three subcategories: “Image power is low angle,” “Equality is eye-level angle,” and “Viewer power is high angle.” In the cartoons, we also interact with the farmers from a vertical angle. The lower position of farmers can be interpreted as high-angle metaphors. These metaphors serve to highlight the vulnerability of farmers and elicit a sense of power in the viewers.

Farmers and Urban Citizens Represent Contrasting Societal Groups

As previously mentioned, viewing arrangements can serve to signify social distance, emotional closeness, and power dynamics. In news cartoons, the coexistence of urban citizens and farmers is characterized by two distinct viewing arrangements. In terms of visual identity referents, the clothes and accessories worn by farmers contrasts sharply with that of urban citizens. Take figure 4 as an example, in which the urban citizen is portrayed wearing a refined suit, a necktie, and glasses. In China, this attire is commonly associated with individuals who possess a high level of education and are employed in white-collar professions. In CDA, linguists pay special attention to “ideological squaring,” which means that texts often use opposing referential choices to build up opposites around participants (Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk1998). In multimodal discourses, ideological squaring refers to the employment of contrasting visual representations of the participants. The opposed dressings correspond to contrasting levels of education and social status between farmers and urban citizens, hence the metaphor opposite social distance is opposed dressing. By this metaphor, the superiority of urban citizens and the inferiority of farmers are highlighted. In terms of standing position, they are placed in opposite “image alignment,” which is the spatial organization of pictorial elements in terms of size, orientation, or distance (Teng and Sun Reference Teng2002). Image alignment functions as a cognitive stimulus, prompting viewers to contemplate whether the depicted elements belong to the same category or not (Teng and Sun Reference Teng2002, 300). The same directional alignment indicates membership in the same category, whereas the opposite directional alignment implies a different category. Accordingly, opposite social position is opposite directional alignment. The contrasting juxtaposition of farmers and urban citizens highlights the disparities in their social status.

Figure 4. “Good Governance in Rural Areas” by Song Hongbing, published on April 27, 2020.

Farmers Are Criminals Who Are Poorly Educated

In some cartoons, such as in figure 5, we can see farmers are equipped with sticks and knives. The Chinese characters on the sleeve mean “eradicating crime and blackmail.” In 2019, China launched a sweeping anticrime crackdown on criminal activities to improve public order. In this social context, sticks and knives activate the category-and-member ICM and stand for weapons. It is easy for readers to identify a “multimodal metonymic chain” here: sticks and knives stand for weapons stand for criminals. Farmers who hold these weapons are bound to be criminals. In the previous analysis, we discussed the metaphor protection is umbrella. Based on the verbal text of this cartoon, the hand is employed as a symbolic representation of the governing authority. In visual grammar, representational meaning involves elements of processes (e.g., actions), participants (e.g., actors), and circumstances (e.g., locations). Any substitution of these elements will lead to the interpretation of metaphors. The action process can also be replaced, giving rise to the action metaphor in which a concrete process is in place of an abstract one. The interaction among the umbrella metaphor, weapon metonymy, and hand metonymy allows for the action metaphor to be inferred government cracking down on criminals is the big hand eradicating umbrellas for farmers holding weapons. The explanatory note accompanying figure 5 states that the low level of literacy and education among farmers leads to their weak legal awareness and lack of necessary legal knowledge. The statement suggests that farmers are more prone to breaking laws. The linguistic comment in conjunction with the metaphors employed in this cartoon serves to highlight the “social role metaphor” portraying farmers as individuals with criminal tendencies due to their limited education.

Figure 5. “Cracking Down on Illegal Activities and Pulling Out Umbrellas” by Wang Yanmin, published on June 21, 2020.

Farmers Are Beneficiaries of Agricultural Policies

In recent years, the Chinese government has implemented a range of agricultural policies aimed at bolstering the agricultural sector, rural communities, and the well-being of farmers as part of the rural revitalization strategy. Benefiting from favorable policy measures, farmers have experienced notable enhancements in their overall well-being and livelihood, particularly in areas such as housing, employment, healthcare, and education. There seems to be no doubt that farmers are beneficiaries of governments’ policies. In such cartoons, two types of multimodal metaphors merit attention: the journey metaphor and the up-orientational metaphor, which uses an upward trend to indicate a life of increasing prosperity.

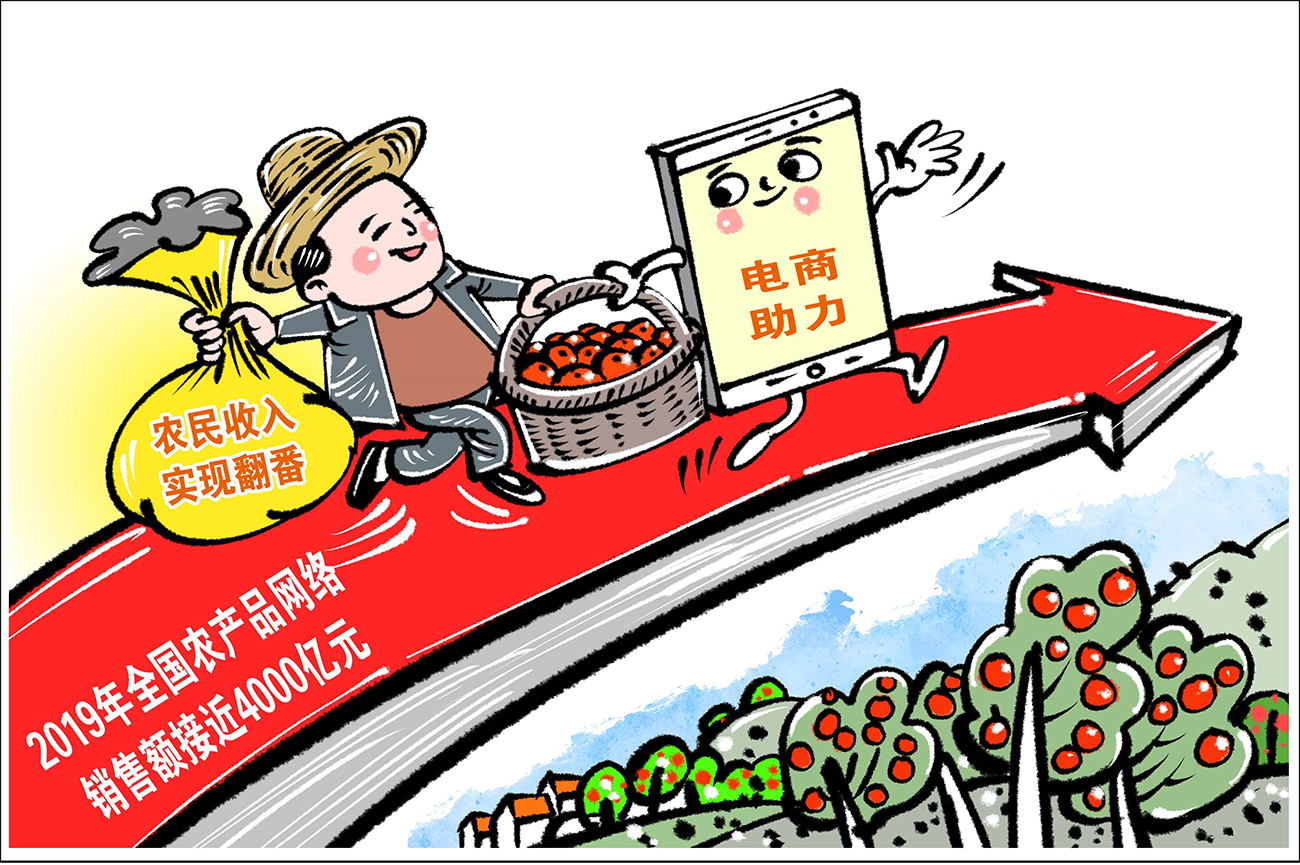

From a cognitive perspective, structure metaphor refers to a metaphor constructed through a highly structured concrete concept. In other words, in a structure metaphor, the structure of a source domain is systematically mapped onto the target domain. The metaphor life is a journey, which embodies the source-path-goal schema, is a commonly observed structural metaphor. In this metaphor, the concept of “life” in the target (person, lifestyle, purpose, etc.) corresponds to the concept of “journey” in the source (travelers, vehicle, destination, etc.; Lakoff and Turner Reference Lakoff1989). Lakoff (Reference Lakoff1993) reformulated the journey metaphor as purposeful activity is travelling along a path towards a destination. Compared with the former prototype, this journey metaphor is preferable for it highlights the dynamic motion and emphasizes goal-orientated life. In figure 6, a variety of metaphors can be discerned. The first metaphor to be discussed is the journey metaphor. The individual depicted in the cartoon is a farmer, identifiable by the straw hat he is wearing. He is seen walking along a path, symbolized by an upward arrow. The verbal message on the bag held by the farmer can be translated as “Farmers’ incomes have been doubled.” These linguistic phrases and the verbal title of the picture provide a clear hint to the target domain: poverty alleviation. The four Chinese characters inscribed on the electronic device signify “E-commerce assistance.” With the visually manifested source domain, the journey metaphor can be extracted as poverty alleviation is a journey or, more precisely, poverty alleviation is embarking on a path toward a destination. Some of the major structural analogies enable the mapping from the source domain “journey” onto the target domain “poverty alleviation” and establish correspondences between different elements within these two conceptual domains, which result in a metaphorical cluster the farmers are the travelers, helping farmers get rich is the destination, the development made in poverty alleviation is the route, and e-commerce assistance is the vehicle. The abstract action process of e-commerce assisting farmers in doubling their income is substituted by the concrete action process of an electronic device pulling the farmers forward. As previously stated, there exists a multitude of conventional UP-orientational metaphors drawing on our experience with the outside world physically and culturally. The linguistic sentence on the arrow states: “The online sales of agricultural products in China amounted to approximately 400 billion yuan in 2019.” The upward arrow in figure 6 signifies the orientational metaphor growth in agricultural sales is upward arrow. The upward arrow conveys a sense of continuity and anticipates the sustainable growth of farmers’ economic prosperity in the forthcoming period. The statement “There will be more in the future” aligns with the metaphorical concepts of more is up and the future is up, which serves as an illustrative example that encapsulates the notion of progress. The farmer’s smiley face fully demonstrates his satisfaction with the poverty alleviation accomplishments and aspiration for a better life. In this poverty alleviation journey, farmers are the main beneficiaries.

Figure 6. “E-commerce Helping Farmers Increase Income and Alleviate Poverty” by Shang Haichun, published on February 3, 2021.

Critical Explanation and Suggestions

The preceding chapters have thoroughly examined the semiotic choices made both within and beyond the farmers’ tangible reality. In CDA, the term overlexicalization refers to the excessive use of specific words and their synonyms. Its visual counterpart can be labeled overmanifestation, which occurs when an excessive number of repetitive and quasi-synonymous symbols are integrated into the overall representation of a group in multimodal discourses (Teo Reference Teo2000, 20). In farmer-themed cartoons, there is a prevalent use of visual semiotic resources that convey negative connotations associated with farmers, including poverty, vulnerability, illiteracy, and powerlessness. Despite their literal differences, these visual resources collectively contribute to the portrayal of farmers in a negative manner. When these semiotic options are exploited to organize a variety of multimodal metaphors and metonymies, the negative implications will inevitably be projected onto the target of farmers. In virtue of the highlighting-and-hiding mechanisms inherent in metaphorical and metonymic mapping, the negative attributes are made more noticeable, thereby directing our attention to the inferiority of farmers. A fairly detailed deconstruction of the tropes surrounding farmers uncovers five main “social role metaphors” built around them. They are economically disadvantaged laborers, vulnerable and powerless takers, contrasting figures to urban citizens, poorly educated criminals, as well as beneficiaries of agricultural policies. Farmers are stereotypically and passively depicted through selected (and often exaggerated) semiotic resources of patched garments, low-quality accessories, outstretched hands, smaller sizes, lower positions, opposite alignment, and specific camera angles. The cartoonists, whether consciously or subconsciously, present distorted images to establish a framework that facilitates the negative assessment of farmers. This framework subsequently contributes to the reinforcement of stigmatization and discrimination. The findings of this investigation compel us to ask why and to further inquire about the underlying causes behind the observed phenomena. The socioeconomic influence may offer a more compelling explanation for the popularity of specific depictions of farmers in these cartoons. Economically, the enduring differentiation between urban and rural populations can be attributed to the urban-rural dual economic system. This system denotes the coexistence of urban and rural economies. The former is primarily distinguished by a system of socialized production, whereas the latter is characterized by small-scale agricultural production. Under this economic system, there is a notable inclination toward urban areas, whereby resources, services, and policies are disproportionately allocated in their favor. The persistent presence of this dichotomy contributes to the widening of the wealth gap, exacerbating disparities in education, employment, and distribution, while also hindering the mobility of populations between rural and urban areas. Ultimately, the progress of urban areas stands in stark contrast to the underdevelopment of rural regions. Alongside the economic disparity, a prevailing sense of urban superiority emerges within Chinese society. Socially speaking, discrimination against farmers in China has been a long-standing issue. China has historically implemented a social classification system wherein individuals are categorized into different grades and ranks. Within this system, farmers are situated at the lowest social hierarchy. As the ancient proverb suggests, individuals who engage in intellectual work hold power, while those who engage in physical labor are subordinate. This widely held belief maintains that farmers are inferior to urban citizens.

In the portrayal of farmers’ images, the mass media occupy a dominant position. From the standpoint of urban elites, news media practitioners tend to impose their negative perceptions onto farmers unilaterally and subjectively. In the pursuit of rural revitalization, it is imperative to recognize and rectify the prevailing discrepancy between the one-dimensional, weakened, stereotyped, and biased depictions of farmers and their actual realities. The subsequent recommendations may facilitate the management of the deficiencies. First and foremost, the media should give careful consideration to the phenomenon of verbal-visual dissonance. This refers to the situation where the implicit visual connotations presented in a media message are incongruent with the explicit meanings conveyed by the accompanying verbal text. To highlight positive images that are consistent with the theme, the media must innovate multimodal metaphors and metonymies. Furthermore, it is necessary for the media to proactively enhance their visual representational strategies. Through the meticulous selection and strategic combination of internal and external semiotic resources, the media make efforts to minimize potential negative mappings in metaphorical and metonymical constructions. Additionally, it is imperative to reduce the visual disparity between farmers and other societal groups. Furthermore, the media needs to remain up-to-date and explore a wider range of multidimensional personalized images of farmers to challenge and eliminate stereotypes. For instance, instead of solely focusing on the economic status of farmers, the media can delve deeper into their spiritual dimensions, showcasing a new breed of farmers who are acquainted with new technology and new ideas. Finally, it is essential to grant farmers greater dominance in farmer-themed discourses to enhance the representation of their viewpoints and increase the overall scope of coverage. After all, farmers’ self-construction and media construction are of equal importance.

Conclusion

Social media platforms serve as lenses through which individuals perceive and interact with the world. However, in numerous instances, the lens through which we interpret visual representations is anything but impartial. In press discourse, news handlers possess a multitude of semiotic options at their disposal when seeking to portray an individual. The decisions they make are never neutral. These semiotic choices can “depict individuals in a manner that tends to either align us with or against them, without explicitly stating that this alignment is intended” (Mayr and Machin Reference Mayr2012, 103–4). In our contemporary society—where media are utilized, and at times manipulated, as a platform for influential entities such as politicians, industry magnates, and religious leaders—the critical analysis of the specific semiotic choices made serves as a valuable intersection between the fields of linguistics, semiotics, and media studies. Multimodal metaphors and metonymies possess ideological significance, as they can efficiently frame perception by highlighting some elements of reality while downplaying others. They are often used to gloss over genuine attitudes and intentions. Therefore, the application of MCMA will lead to a better understanding of multimodal discourses. Thorough scrutiny of multimodal metaphors and metonymies employed in farmer-themed Chinese news cartoons provides insights into the presence of hidden negative attitudes, discrimination, stigmatization, and unequal power dynamics in multimodal discourses. This undertaking not only demonstrates the operational mechanisms and credibility of metaphors and metonymies in shaping images but also establishes that overmanifestation, size, viewing arrangement, camera angle, and image alignment were good candidates for the evaluative aspect of visual metaphors and metonymies. The contribution mentioned above will greatly enhance the advancement of the theoretical framework of MCMA, necessitating the integration of theoretical contemplation and empirical validation. An interdisciplinary approach will enable scholars to conduct more in-depth research on media images of other groups. In light of the concerns raised regarding farmer-themed news cartoons, this study proposes several feasible recommendations for future image construction endeavors. These proposals have the potential to effectively address and eradicate deep-rooted biases, while also fostering positive social perceptions of farmers. Multimodal metaphors are by their very nature open to multiple interpretations, which can significantly differ among viewers with diverse cultural backgrounds. Although this investigation incorporates a combination of quantitative and qualitative analyses, it is important to acknowledge that subjectivity is inevitable. Given the limited quantity of cartoons analyzed in this study, the findings drawn are tentative, which would require further investigation. To enhance the objectivity and verifiability of the analysis, it is fundamental to build a larger corpus and employ more comprehensive quantitative and comparative methods in future research.