That’s what the world is after all: an endless battle of contrasting memories.

—Haruki Murakami (Reference Murakami2011, bk. 2)Mad or tame? … Such are the two ways of the Photograph. The choice is mine: to subject its spectacle to the civilized code of perfect illusions, or to confront in it the wakening of intractable reality.

—Roland Barthes (Reference Barthes1981, 119)As a result of the triple disasters on the March 11, 2011, in Japan (3.11), there has suddenly been a heightened awareness of and the urgent need for remembering the events of the past to prepare for and possibly reduce damage from a future disaster as well as to transmit “the lessons learned” effectively to future generations. However, such a call for preserving the past memory has met with a curious confusion in the everyday usage of the two terms: memory and record. While the terms bear no etymological relationship in English, in Japanese these two terms show an uncanny resemblance in their character compounds: kioku/記憶 ‘memory’ and kiroku/記録 ‘record’. Both words share the same Chinese character ki ‘to inscribe/mark’, while the accompanying character, either oku ‘to recollect’ for memory or roku ‘to record’ for record, makes the semantic distinction between the two. Since the triple disasters, national and popular discourses surrounding preserving ki-(oku/roku) have been pervasive, especially regarding the process of reorganizing disaster-damaged material culture, to the extent that the two terms appear to stand for the same meaning in their usage to indicate anything by which the past event is remembered (omoidasu, literally “pushing out a thought”). Lexicographically, however, each term has a distinct meaning. The authoritative dictionary in Japanese (Koujien) defines “record” (kiroku) as “the act of inscribing a factual text for a later usage,” while “memory” (kioku) is “the act of remembering or the content of remembrance.”

The emergent conflation of the two terms is well captured by the March 2012 release of a picture book by 20th Century Archive Sendai, a local nonprofit organization in Sendai, titled 3.11: Record of Memories. Interestingly, the organization’s description of the contents mentions only photographic records being documented in the book but not memories (20th Century Archive Sendai 2012), illustrating that, semantically, the act of remembering and the recording of remembrance are separate experiences. Pragmatically, however, they are two sides of the same coin. 20th Century Archive Sendai’s work is only one of many diverse endeavors that use the same object—the photograph—and its associated techniques and technologies as the conventional instrument for communication and (re)presentation of the past.

In this article I discuss two distinct “photograph laboratories” that have emerged after 3.11 in which thousands of photographs are processed and subsequently transformed into memory-record chimeras. In the two subculturesFootnote 1 within the larger milieu of postdisasters in Japan,Footnote 2 photographic objects are processed with quite different ethos and pathos. Yet at the same time, they are used equally for achieving the collective goals of commemoration and of communication to future generations about the danger of a large-scale disaster. The first laboratory is a photographic recovery project (PRP) that cleans up tsunami-dampened photographs, organized by a group of mostly short-term volunteers. This group’s ultimate goal is to return the photographs to the original owners, as these objects are believed to be tokens of the owners’ lived memories. The other laboratory is a post hoc digital archive project (DAP), Michinoku Shinrokuden, at Tohoku University’s International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS) that aims to archive “all possible memories, records, case histories, [and] knowledge concerning the 2011 Tohoku earthquake” in order to “hand down the disasterography to national and international communities as well as future generations.”Footnote 3 For them, a collection of digital photographic records regarding 3.11 serves as a mnemonic tool for future remembrances of the past, believed to be a necessary solution for reducing the potential impact of a future disaster.

Following Galison’s (Reference Galison1997, 19) critical analysis of the intercalated development of image and logic traditions in the history of physics, I will compare and contrast two traditions of image and logic—mimetic, “homomorphic” representation by iconodules and statistical, “homologous” representation by iconoclasts, respectively—in their pragmatic usage of photographic representations in post-3.11 Japan. This article focuses on the following contention: each subculture equally makes claims about the past disasters, while using the same object in substantiating their distinct claims. Through an ethnographically grounded differentiation of subcultures, I will analyze whether or not these different subcultures come to calibrate a semiotic “trading zone” (Galison Reference Galison1997, Reference Galison and Gorman2010) in achieving the collective goal of (re)presenting the disasters to future generations, while preserving individuals’ particular beliefs and memories of the disaster.Footnote 4

What distinguishes the two subcultures, notwithstanding each group’s perception of the object, is the modality of object. Whereas the PRP works only with printed photographs whose physicality references the various temporalities of the predisaster time, the DAP mainly deals with digital images taken after the disasters that are, therefore, further distanced from signs of life before the disasters. In other words, different modes of the photographic object, physical or virtual, are asymmetrically mapped onto the referentiality of the photograph. On the one hand, the salvaged photographs used by the PRP volunteers are indexical (contiguous with) and iconic of (resemble) the absent figures and/or the backgrounds framed in the pictures. These photographs primarily stand in place of the absented presence in the recovered photographs since most of the time the people who recover the photographs and the owners of the recovered photographs are mutually anonymous to each other. On the other hand, the DAP’s archived virtual records of the postdisasters are iconic and indexical of the disasters and are thus the type of signs that, one way or another, come to simulate some aspect of disaster in the present and for the future by “making present again that which was previously absent” (Leone and Parmentier Reference Leone and Parmentier2014, 53; emphasis in original). Those records not only come to be interpreted as resembling something about the aftermath of a disaster but also as indicating the growing reservoir of the collective memory, or terra (in)cognita, of disaster.

In the post-3.11 disasters context, those two versions of photographic records are used equally by the two different subcultures as symbolic instruments of “noninterventionalist objectivity” (Daston and Galison Reference Daston and Galison1992, 120; Reference Daston2007). Therefore, the preexisting convention regarding the photographic object enables both labs to use the photographs to make plausible claims about the past disasters in the present.

Given this background, the guiding questions for this article are the following: Through what sign processes are those semiotic tokens of these past disasters interpreted as symbolic, or as conventionally agreed upon alibis, within and across various subcultures? How does a struggle of interpretative habits (Parmentier Reference Parmentier1997; Morimoto Reference Morimoto2012) both enable and constrain the growth of the very instrument of communication that is believed to preserve the “reality” of the disasters? And finally, what is the rhetoric of the photographic object, if there is any, in the context of disasters, and how can the same object deploy multiple instrumentalities in its usage, while simultaneously “standing in” as and “making present again” the “objective” memory record of the disasters?

I address those questions by examining the role of the object (both preexisting and newly constructed photographic images in particular) as an instrument of communication and a sign-vehicle in culture in order to assess the object’s rhetorical effects vis-à-vis a large-scale disaster that is, as Blanchot puts, “an excess of experience, and affirmative though it be, in this excess no experience occurs” (Reference Blanchot and Smock1995, 51; see also Parmentier Reference Parmentier2012, 236). Here I am particularly interested in literatures in material semiotics in which the order of objects and the ordering of objects mutually constrain the perspective of the world (e.g., Miller Reference Miller and Ingold2002; Edensor Reference Edensor2005; Silverstein Reference Silverstein2005; Kockelman Reference Kockelman2010; Manning Reference Manning2012; Nakassis Reference Nakassis2012). In addition to such a reciprocal relationship between subject and object in which a cultural process of organizing the order of object masks the ordering of subject, I will discuss how a technologically mediated ethical stance toward the object—the shifting distance between object and subject in relation to each otherFootnote 5—influences the (re)presentation of the disaster—the representing subject—according to different traditions.

With the following ethnographic instances that juxtapose two photographic laboratories, I will illustrate how the rhetoric of the disaster-related photographs is located in the conventionalizing alibi of each group’s varying semiotic stance or, as Galison puts it, “a matrix of beliefs” (Reference Galison1987, 277). In the context of a sudden disaster, both the duty to remember the past and the hope for alternative trajectories of the future are grounded in a particular object. The very usage of the photograph in the present further conventionalizes the already agreed upon idea of the object; without such specific usage the photograph is systematically natural and arbitrarily cultural, that is, antisemiotic. Therefore, this article provides an ethnographic case that exemplifies a “circle of semiosis” (Leone and Parmentier Reference Leone and Parmentier2014) in which the removal of interpretation, that is, the regimented meaning of object, is evidenced in particular usages of the same object that cites the presupposed meaning of the object to validate its usages. In this process the photography is used to (re)present simultaneously as a rhetorical chimera, ki-oku/roku of nature and culture (cf. Batchen Reference Batchen1997).

The Signs of Survival

One of the earliest tasks of the disaster relief efforts focused on cleaning up material debris unearthed after the tsunami. The amount of waste collected in the three prefectures (Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima) had been estimated in 2011 to be around 24 million tons, about 1.7 times more than the waste produced by the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in 1995. Much of the waste has since been sent to temporary landfills, where it was then classified into different categories to be processed in different ways.Footnote 6 In spite of all the machinery used in this effort, there was still a need for human labor. As many volunteers liked to say, “there are things only human hands can do.” Indeed, there were things that machines did not care about, but humans did—photographs, for one. Unlike other objects belonging to the general category of gareki ‘waste’, photographs discovered on the ground were picked up carefully and sent back to the volunteer centers to be processed, as if they somehow had the special capacity to store all the memories of the disasters (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Tsunami-damaged photographs. Clarity has been reduced to obscure the identity of the people in them. Photograph by the author.

A brief history of the photographic image reveals how it can be one of the many potent “signs within society” (Saussure Reference Saussure and Baskin[1915] 1966). Around 1837, upon the development of the prototypic photographic instrument, or the daguerreotype, photographic technology was announced as “not merely an instrument which serves to draw Nature; on the contrary it is a chemical and physical process which gives her [Nature] the power to reproduce herself” (Daguerre Reference Daguerre and Trachtenberg[1939] 1980, 13). With the gradual mechanical sophistication of this art of mimesis, a new mutation of the concept of objectivity emerged. The possibility of technology functioning in a neutral, automatic fashion is, according to Daston and Galison (Reference Daston and Galison1992, 111), what led to the late nineteenth-century belief that “the photograph does not lie.” By photography’s supposed ability to impartially capture its object or to record the “message without a code,” as Barthes (Reference Barthes and Heath1977, 17) puts it, photography, a “perfect analogon” (Reference Barthes and Heath1977, 17; emphasis in original), has become the symbol of human nonintervention par excellence—“mechanical objectivity” (Daston and Galison Reference Daston and Galison1992) so conceived.Footnote 7 Such a technology of mechanical reproduction emancipated, as Benjamin articulated, “the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual” (Reference Benjamin[1936] 1968, 224). Photographic technology thereby enabled the magnification of the distance between belief and action by communicating its plausibility, on the one hand, as the unmediated resemblance to an object and, on the other hand, as a narrowly selective transparency (Sontag Reference Sontag1977) where the photograph was imagined to passively capture the object, while filtrating a discriminating interpretation of the mind as a part of objective, natural reality. For its utility as both a naturalizing mechanism and conventionalized instrument of culture, Barthes considers the photograph’s sign process to make “an inert object a language” and to transform “the uncultured of a ‘mechanical’ art into the most social of institutions” (Reference Barthes and Heath1977, 31). For Barthes, the photographic code signifies a naturalized image of culture.

The semioticity of the tsunami-damaged photographs aside, they had to be “re-possessed” in the storage units located just a short distance from the main building of a nonprofit organization in Tōno city, Iwate prefecture. Those photographs came to the temporary PRP lab sometimes from the hands of the volunteers on the ground who happened to discover them among other ruined objects and other times from local survivors who asked volunteers to do something about their presence because, in the honest words of one surviving elderly woman, “those things are very creepy.” Indeed, the misplaced photographs of people were “creepy” because they indicated that the people in the photographs existed before the disasters without further indicating their safety after the disasters. In the postdisasters context, the salvaged photographs had a particular aura of authenticity of the disasters that conveyed both hope but also devastation. The one thing that was tacitly agreed upon by the volunteers was the necessity of cleaning those damaged photographs, which stood as a potent alibi of the devastating natural disaster that ruined many people and things. Such objects, evoking a sense of loss, support Pelling’s pragmatic definition of natural disaster as “shorthand for humanitarian disaster with a natural trigger” (Reference Pelling2003, 4).

If the volunteers’ effort to clean up the disaster debris provided an on-the-ground perspective (mushinome ‘bug’s-eye view’), the DAP researchers’ effort to put together a collective record of the disasters operated with a view from above (torinome ‘bird’s-eye view’). In a laboratory located on the thirteenth floor of a fourteen-story building, the office windows offer a panoramic view of the coastal side of Sendai City, Miyagi prefecture. Akihiro Shibayama, the director of the participatory 3.11 digital archive projects “Michinoku Shinrokuden,”Footnote 8 launched by Tohoku University, International Research Institute of Disaster Science, told me that he “could see the devastation after the tsunami from the windows here.” Introducing me to the organization of the lab, he pointed to the other side of the lab: “Those workers are tagging photographs according to what they believe to be the best representative characteristic of each.” Unlike the damaged photographs on the ground, the photographs in the DAP, although they depicted the aftermath of the disasters, had to be “linked” to some aspect of the disasters.

Composed of specialists from many different areas—a system engineer, survey researcher, GIS programmer, archivist, and disaster researcher—Michinoku Shinrokuden takes as its mission the project of archiving virtually everything relating to the 3.11 disasters. As one of the projects among the seven subdivisions of IRIDeS, the role of the project is to provide primary resources representative of the disasters for researchers and laypeople alike. Its goal is not only to promote cutting-edge disaster research but also to preserve the memory of the disaster that “shall not be forgotten” in order to prepare for a future disaster. “We need to come up with a mechanism or more properly said a culture,” Shibayama reckoned, “where people kinetically, if not consciously, remember the hows and whats of disaster. You know rajio-taisō [radio calisthenics]? When the music is on, we habitually know what to do without thinking. That’s the kind of habit I want to promote through this disaster archive. We need a disaster tradition.”

The tagging workers, who sat furthest removed from the windows in the office, right by the director’s desk, gave tags (taguzuke) rather mechanically to the endless collection of photographs. I peered over the shoulder of one of the taggers at work as he described his internal logic of tagging photographs: “This I would say is damaged building, tsunami, and gareki. That one I would say house, soaked, tree, and car.” To a mere untrained observer like myself, his tagging convention seemed arbitrary. Although some of the photographs portrayed highly devastated scenes from the disasters, the tagging worker did not seem to be disturbed at all by them. He moved from image to image habitually, as if moving his body in time with familiar music.

Although at first I did not know the significance of this tagging effort, Shibayama explained to me, “Tagging allows people to search what they want from the vast number of items in the database. Now we have over 300,000 items [as of 2013] in our system, and soon enough we will get even more. We need an ordered way to consistently retrieve the records.” The excess that depleted the human capacity to experience the disasters two years ago (à la Blanchot), now became a question of countering the absence of memory with an effective means of retrieval. In the digital archive lab, the frailty is attributed not only to human cognition but also to the medium of recording. “We should not let go of good images into oblivion, should not let them decay or become damaged,” said Shibayama, adding, “we need to digitalize what we can while we can.”

According to Shibayama, the digital is what lives beyond the death of the physical. Ringing true to this characterization, the PRP’s struggle with cleaning tsunami-damaged photographs certainly underlines the frailty of physical photographs. With the ontology of the photographic object with which the PRP coped in mind, I asked Shibayama: if there were no longer an original of the copy, would the copy be the original? Ignoring my question, he replied from the perspective of an earthquake architectural engineer: “Having something is better than nothing. For example, for my profession I cannot trace how an earthquake hits a building if there were no piece of building left.” Our misunderstanding here sheds light on the fact that tracing a past can be differently motivated depending on different subcultures. I further asked about a kind of perception that ascertains resemblance between an original and its copy, despite its spatiotemporal displacement; I assumed, thinking along the lines of the PRP volunteers, that the image in each photograph was perceived to be significant. He, in turn talked about the logic driving the desire to discover contiguity, favoring a more stereotypically scientific vision of a part-to-whole relationship.

Despite the difference in our interpretative stances, the actual experience of tagging photographs seems to privilege the image over the logical relationship between the photographs. One of the tagging workers told me about her work: “I like tagging more than other types of work I do such as collecting info [sic] about disasters from websites. Because when I tag, I can exercise my judgment on what each image represents. But sometimes I feel this sense of guilt from looking at those images without having actually seen the sites.” I asked her how people could agree on how to tag each photograph if each worker exercises his or her own judgment. After giving me a puzzled look, she answered: “What you see in each photograph is very clear and intuitive. … You should not make any mistake.” Although her comment suggests that the act of tagging follows the first meaning of tracing, that is, discovering resemblances, what the act of tagging emphasizes more is people’s ethical responsibility toward the past, which is expressed with the negative ethical imperative of “one shall not.” This imperative seems to stand at the intersection between memory (kioku) and record (kiroku) where, in the act of the remembrance of the thing past, a vestigial subjectivity survives beyond the object’s signification itself.

Recovering, tagging, and remembering: all are privileged acts engaged in only by the survivors of disaster. At the same time, such acts evoke and further beget some degree of guilt, which at times is expressed as a sense of creepiness, as in the local survivor, or the more conscious feeling of guilt experienced by one of the taggers as she scans through images related to the disasters. It is not a coincidence that many memorials such as the Hiroshima War Memorial and the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake memorial (to name a few) feature famous signs, plaques presupposing the individual’s moral duty to remember, while explicitly constraining the visitor from forgetting. Whether dealing with physical or digital photographs, someone needs to witness something in these objects while processing them. Ginzburg reiterates Benveniste’s observation that one of the words in Latin for “‘witness’ is superstes—survivor” (Reference Ginzburg, Tedeschi and Tedeschi2012, 179), and to survive is to stand in the place of something lost. Therefore, the more survivors there are, the more representations of the past may succeed. For both traditions, in the act of working through, the photographic object comes to stand in for the privileged view of the survivors and their ethical duty for remembrance. The question is how this sense of duty is calibrated through the process of “memory work.”

Memory Work: Ordering Indexicality

“Today is the first day for me to run this session, so please be patient with me.” The supervisor of the PRP lab in Tōno, a woman in her thirties, excused herself, announcing the absence of an expert in the lab that day. Inside the small, dusty storage room, farming tools were placed without much attention to aesthetics and order. There were three large transparent storage containers full of lukewarm water and six chairs; chairs were placed on each side of each container for volunteers to work in pairs. There were at least four rows of laundry ropes stretching from one side of the wall to the other, upon which hung hundreds of plastic clips holding nothing. Only later did I find that the ropes and clips were there for hanging up the cleaned photographs to dry like laundry on a verandah. Six of us, including a supervisor, were there to hang the photographs in a very specific order.

“I have done this only twice,” she continued as she wiped some sweat off of her face from the sizzling August heat. Expertise was a rare trait in the room full of transient nonlocal volunteers, and in general this has been one of the difficulties with the postdisaster recovery and reconstruction efforts related to the 2011 disasters. Sociologist Hiroshi Kainuma is one prominent figure whose work sheds light on the predisaster depopulation issues in the Tohoku region. His claim is simple but powerful: the 2011 disasters only exacerbated the preexisting trend of an aging society and depopulation in the peripheral areas in Japan. Although a large-scale disaster physically destroys many structures, it also reveals the stability and rigidity of certain social structures (Kainuma Reference Kainuma2011; Morimoto Reference Morimoto2012). The relationship to the photograph, the way it is said to come to represent something, is one such manifestation of what Oliver-Smith and Hoffman (Reference Oliver-Smith, Hoffman, Hoffman and Oliver-Smith2002, 10) call a “deep social grammar.”

With as much authority as she could muster, the supervisor described to us that each photograph was preserved digitally first to create the photographs of photographs, before being cleaned, and then numbered in order to track them later. She emphasized, however, the importance of preserving physical photographs, and this digitalization process was, unlike the effort by Michinoku Shinrokuden, just a safety measure: “This is just for the record [kiroku].” According to the supervisor, there were more than 3,000 damaged photographs in the depository as of the day, and our task was to clean as many photographs as we could. Then she put on gloves and grabbed a painting brush to demonstrate how photographs were to be cleaned. “First,” she explained, “you soak the photo in the water, and then slowly brush the dirt off of it. As you can see, the ink from the photo comes off, especially where it is yellow. Please take off as much dirt as you can, but please make sure to save the faces on the photos as much as you can, so that we can hopefully find the owners!”Footnote 9 As we listened carefully to her instructions, we became nervous: “what if we wash off a face?” one girl asked, timidly. “Well that happens,” said the supervisor, rather apathetic, “but do what you can.” She then assigned a pile of pictures to each pair and two brushes and gloves, telling us, “Start off the memory [kioku] work!”

Except for the supervisor, all of us were inexperienced at this task. We introduced ourselves to each other and talked a bit about ourselves. When her turn came, a woman of around sixty spoke, passionately: “I came to Tōno, all the way from Kumamoto [over 900 miles away] to do this! I saw it on TV, you know. I brought a few picture frames with me to frame photos so that I can return them to the owners. They must want these photos back. They are their memories.” Her comment was the signal for all of us to stop procrastinating and get to work.

We were all quiet as we began our work, as if consumed by the task itself. The task was very delicate and stressful. Many photographs were badly damaged, and I could see even before working on them that some of them were not recoverable. I intentionally put those more damaged pictures to the side of the pile to avoid working with them, and I saw others doing the same. It was hard, however, to take my eyes away from them; they somehow articulated the impeccable sign of “the anticipated absence” (Parrott 2010, 133) of the owner, and the only way to guess at this riddle of life and death was to reverse the Barthesian paradigm of the subject-object relationship in photography (Barthes Reference Barthes1981, 76) by tracing back “photographic referent” in those objects in front of us. Each photograph must have been taken somewhere for some reason by someone, indexing some distanced time and space as its internal record. Underneath the figure of each photograph lies the context of its (re)production. As nonspecific as this context might be, its alibi of “having been there” is undeniable. The photographic referent, therefore, invites its captives to the “evidential paradigm” (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg1979), like a detective who traces back clues or a hunter who deciphers the mute tracks of a prey. Whether or not the detective work or hunt is successful, a story of tracing emerges as the second-order testimony that validates the factuality of a trace in the present (see Ricoeur Reference Ricoeur, Blamey and Pellauer2004, 175). “They must want these photos back,” the older woman said with such clear and distinct determination as if she knew, because of the memory work, that the owners had survived. If the dampness of the photographs is indexical of the tsunami, then the cleanness of it is indexical of the effort to undo the disorder created by the former. The volunteers on the ground recorded the dampened photographs as the tokens of their memories of the disasters.

In contrast, in the lab in Sendai tagging digital photographs is only the first step of constructing a participatory digital archive. Each photograph needs to be organized with an identity of its own with a description of its contents and the contexts of production. Creating this organizational layer of data is essential for sharing contents across communities, and as an international archiving project, any useful data needs to be organized based on a cross-institutionally agreed upon schema in order to achieve commensurability across different archives. IRIDeS’s Michinoku Shinrokuden is a part of a larger consortium of projects related to the 2011 disasters that includes Hinagiku by the National Diet Library of Japan, the Kahoku Shinpo Disaster Archive, the NHK Great Tohoku Disasters Archive, the 2011 Japan Disaster Archive by Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University, and many others. Ideally, therefore, each item in the Michinoku Shinrokuden should include its own unique call number, the creator’s name, tags, the time and place of recording, geographical coordinate, and so forth, all of which lexical sets are shared among archives. The actual collaborative mechanism is much more technologically complex, and it is beyond the scope of this article. For the purpose of the current discussion, however, it suffices to point out that much of the processing of digital photographs involves inscribing a second-order description of each data point, that is, metadata.

Metadata proved to be an annoying issue for Shibayama and others working at the digital archive. “Many news sites have good pictures and articles,” he told me, “but they have no metadata to be able to be incorporated into our archive.” His frustration reveals at least two implications for the process of creating metadata. First, there is a lack of standardization of archiving digital data. This lack of standardization reveals that one of the symbols of globalization—the World Wide Web—is in reality a collection of localized schemata. The conundrum of metadata sheds light on the constraints rather than the openness of web-based information; the searchability of data is only equivalent to the data’s robust metastructural organization. Constructing a user-friendly archive, therefore, is about subtly training the user to accept the structured metadata; any skilled user needs to know the metapragmatics of data, that is, the correct way of using the structured system of data and “trained” way to make judgments about data. However, presumably, most users would type a keyword they think of and get a list of items associated with the specific search term without realizing that those items have been preselected, processed, and categorized in a certain way. The construction of a database is one illustration of how digitalized data are never an aggregation of pure denotative information but rather a set of connoted/mediated information.

From this perspective, the often-debated concept of “reconstruction” (fukkō), which may be defined in many different ways by different individuals in Japan, has to be temporarily suspended for the sake of the structural robustness of archive based on “trained judgment” (Daston and Galison Reference Daston2007). For example, if you search for reconstruction (fukkō) on the Michinoku Shinrokuden archive β1.0, results would only contain archived items from half a year after the disasters, thereby constraining the semantic field of the term to cover activities that began after recovery. However, when the term “recovery” (fukkyu) is put in, results bring up items from the same time period plus items categorized as occurring one month after the disasters or less, indicating that the semantic fields of the two terms (fukkō and fukkyu) are convergent rather than divergent. There are many counterarguments to this kind of semantic convergence, such as the fact that different locations go through recovery processes each at a different pace. Such an argument is testable by further parsing the result of these two searches by observing the differences shown in the spatial information, that is, eliminating the original result by adding a specific time and space to observe which region(s) was faster in recovering and reconstruction. Moreover, different accompanying tags are associated with each of these keywords. In the case of reconstruction, many of the search results are tagged with “people,” whereas for recovery most of the items are tagged with “building.” This association would seem to specify that the term “reconstruction” stands for people instead of things. In order to arrive at such a conclusion, one needs to be equipped with a “disciplinary eye” (Daston and Galison Reference Daston2007, 48) and an extra motivation to see beyond mere images calibrated according to desired keywords.

This schism between the experience of the trained and untrained eye is made possible by the archive’s virtual, linear memory storage. This supra-individual capacity for programmed information retrieval renders the archive’s usage as the method of identifying iconodule and iconoclast that divides up “an epistemic passivity on the part of those who viewed them” (Daston and Galison Reference Daston2007, 360) and a distanced gaze, that is, a view from above (Haffner Reference Haffner2013). My observation of the process of making such a view from above suggests that the specific rule of categorization is a rather subjective decision, in the guise of an argument for promoting the efficiency of the categorization process. The creators also presuppose what they deem to be the appropriate meanings of such keywords, although at the same time these presupposed meanings get further relayed to the user of the archive. In this sense, the DAP has a tendency to reinforce preexisting knowledge of the disaster instead of suggesting an alternative, more creative understanding of disaster.

Second, when attempting to establish an archive, value is placed on the total number of searchable items in the inventory. This is perhaps because of the implicit competition among other existing archives. Although the coexistence of multiple digital archives has been framed as collaboration rather than competition, there is certainly a question as to the need for having more than one archive that performs a somewhat similar operation. Therefore, setting the standard metadata schemata is a political process. The construction of an archive with a consistent set of metadata is a strategy not only for standardizing the particular epistemology of vision but also for governing the order of the mnemonic techniques with which any potential user hopes to retrieve the organized past. As Schnapp points out, the word “archive” has its root in the Greek word “αρχειoυ” or “government”; in its usage, “archive connotes a past that is dead, that has severed its ties with the present, and that has entered the crypt of history only to resurface under controlled conditions” (Reference Schnapp2008; emphasis in original). An archive, as a stipulating process of vision, reverses the indexical order (i.e., a causal vector; Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003a; cf. Inoue Reference Inoue2004) of photographic reference such that it is no longer each individual photograph’s point of reference—for example, a person in the photograph who might still be alive—that constitutes the photograph’s message but rather a hidden algorism that generates a sum of instances that fulfills the message sought.

To engage in some “memory work” with the photograph in both subcultures is, therefore, to “indexicalize” it,Footnote 10 that is, “to change structures, to signify something different from what is shown” (Barthes Reference Barthes and Heath1977, 18–19) by inscribing it with a set of constructed codes. It is appropriate, therefore, that the supervisor in Tōno referred to the recovery project as “memory work,” since in the postdisaster context all memories are, though to various degrees, worked according to presupposed beliefs about the meaning of the photographic object. What is at stake, therefore, is a shifting rhetoric of the photograph vis-à-vis its usage by different traditions with different ethical standard toward the past and future. How, then, is the photographic object believed to stand in for and make present again the past in the present, and why?

Iconodule and Iconoclasm: The Double Ethos of Shikatanai

Take a weathered photo, soak it gently in water, brush off any dirt, and tag it onto the laundry rope. In a small room full of people and objects, the photo recovery volunteers were mechanically reproducing our now-routinized act. The room was enclosed in a bubble of Zen-like contemplation, shutting us off from the ruckus of disaster-relief work outside.

This bubble soon fractured when one of the girls emitted with a small, sharp scream: “Sorry, the face is gone!” Quickly approaching her side, the supervisor assured empathically, “No worries; see, there are still other faces. You are doing fine. Even if you wash them off, it is shikatanai [there is no way to do it].”Footnote 11 This incident disclosed our fallibility and seemed to relax all of us. The magic spell of the word shikatanai restored the secure environment that allowed us to tackle the almost impossible task of saving every face; sometimes we did wash off the faces, but we did it because simply shikatanai. Soon we became more talkative and exchanged our impressions of the photographs, as if the photographs afforded a playground of beautifying imagination of the disaster (Sontag Reference Sontag1965).

“What a cute baby girl!” one woman commented, “she is in kindergarten in this picture.” Another followed, “Look she is always with her father. She must be loved.” The third one joined, “Here is another picture with him too. He kind of reminds me of my father.” The fourth girl added, “Oh, look, in this picture she is already in elementary school. Her hair grew, but definitely looks like her mother,” and the supervisor added more, “In mine she looks like she is in college. I wonder if she has a boyfriend.” Being the only male in the room, I shyly said, “Do you think the girl in this other picture is her too? She is wearing a wedding dress.” The older lady quickly jerked her head in my direction and exclaimed: “That’s her. Look at her husband, she found a good-looking one! I want to work on your pile, please! This dress looks like the one I wore for my wedding.”

As time went by and many photos of this unknown family were tacked with the clips onto the ropes, we had constructed a full story of the girl through the series of photos: we imagined that she is a married woman of around thirty with two kids. She is a housewife and lives a very happy life with her handsome husband. She looks like her mother and has a younger brother who looks more like her father, who loves her deeply. None of us in the room dared to challenge this fabricated story; the photographs evaded our ability to deny the (absented) presence of this particular person and this particular family. The anonymous girl whose name we had no clue about just hours ago now became alive—it was as if she was a good friend in each of our lives. We did not imagine the story; rather, we thought the story was in the photographs whose recovered images we (faithfully) followed. There was a presupposition that the photographs necessarily reflected the life of the figures in them; only the tsunami interfered with their correct representations. Working with the physical objects to recover what they were turned us into iconodules whose goal was to preserve figures, not the ground.

There is something about the concrete object standing, both spatially and temporally, in between the nonvictims and the suspected victims that enables the identification between the two. In retrospect, all we did was to simulate the mysterious and all-powerful sublime nature that had defaced millions of other photographically recorded lives, uncovered on the ground or still missing elsewhere, by first soaking the images of people in water, adding stress to challenge their vitality, and then pulling them out to check their integrity. As the conventional ethos of shikatanai warranted, our power was frail compared to that of Nature. The difference between Nature and us, the volunteers, is that we genuinely hoped for the return of the photographed subjects; we believed that they represented the people in them accurately, and at the same time we selected the objects of “defacement” (Taussig Reference Taussig1999) in a covert attempt to reveal those gradually forgotten, unheard voices of the actual victims of the disasters. In a series of simulacra, the victims nevertheless left impeccable traces of the time and space before the tsunami. The mark of ruin, therefore, served as the undeniable “reality effect” (Barthes Reference Barthes and Howard[1968] 1986, 139) that bestowed the evidentiality of “the thing has been there” (Barthes Reference Barthes1981, 76; emphasis in original). Such an effect reveals the unsaid “punctum” (57–59) of ruined photographs in the context of postdisaster relief effort. In this particular critical space of hope and devastation for survival, what pulled us toward those ruined photographs was not the question of the ontology of object, or whether it was authentic or mechanically reproduced replica. Rather, it was the persuasive rhetoric of its impeccable here-and-nowness that removed any interpretation to deny this factuality. For the PRP, each photograph conveyed the irreversibility of the past in the present: Shikatanai—there is no way to do it. However, the other subculture did not seem to partake in this idea.

Encountering the “unprecedented disasters [mizou no saigai],” the scientific community was reevaluating its efficacy. “There is no way to be able to accurately predict the timing and location of an earthquake,” prominent seismologist Geller warned yet again after the 2011 disasters. In his book published after 3.11, Geller problematized the history of the science of earthquake prediction and its continuous hesitancy to accept the conclusion that there is no way to make such predictions. Geller also discusses the amount of governmental support a scientist gets for related projects, suggesting how the national government is promoting the sophistication of scientific foresights (Reference Geller2011; Geller and Jackson Reference Geller and Jackson1997).

Initially started as an ambitious and pragmatic long-term project of researching the possibility of earthquake prediction, earthquake prediction science has received expanded federal government funding for completing its mission. Over the course of thirty years, the argument of this possibility turned into a certitude, promising the future success of earthquake prediction, although in reality, many of the researches involved depended on ad hoc searches for signs of earthquakes that could help identify a future one. Although it is certainly the case that seismologists and earthquake engineers alike have not been able to provide accurate predictions and are still trying to prove otherwise (Geller Reference Geller2011), this is not to say that such an effort has been useless outside the realm of science. According to the most recent prediction, the Nankai Trough triple earthquakes would produce an estimated 320,000 deaths (Yomiuri Shinbun 2012). This prediction has been effective (in combination with the horror of 3.11) in raising the awareness of the risk and danger of a future large-scale disaster in Japan, acting as a sort of shock therapy. In the case of 3.11, however, many scientists had predicted a different epicenter. This inaccurate prediction now invites skepticism toward the probability of the originally predicted site to actually be the next one. At the same time, there are voices among the survivors who assert that scientists’ occasional lectures and workshops in coastal areas about the danger of a large-scale earthquake and tsunami helped them to escape immediately.

As a part of the scientific effort to counter disaster, Michinoku Shinrokuden has two main goals. One is to collect every possible memory, record, example, and piece of knowledge about the disasters from multiple perspectives in order to facilitate interdisciplinary approaches in understanding the 2011 Great Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, as well as sharing the gathered knowledge with the public. The second goal is to apply the lessons learned from the 2011 disasters about the nature and scope of an infrequent, large-scale disaster in taking various measures to meet the now-expected Nankai Trough triple earthquakes (Imamura et al. Reference Imamura, Sato and Shibayama2012). Although it is not the ambition of the project to predict a future disaster, it wants to make scientifically facilitated efforts to prevent (bousai) and reduce (gensai) the cost of a disaster. Therefore, a large sample size would potentially allow researchers, planners, and risk managers alike to use the archive to simulate many probable situations that could occur in the event of a future disaster. In other words, shikatanai is not an acceptable moral escape for the ethos of science. The duty of science is to find some way to make any improvement. Shibayama himself voiced such sentiments: “I regret gravely, as someone who has been studying about disaster, not to be able to reduce the impact of 3.11.”

The DAP presents itself as one way to find a solution for communicating the memory of a disaster to future generations. However, the archive faces a significant problem relating to the rights of publicity or so-called right of likeness (shouzou ken) in Japan. In fact, Shibayama once told me that there are more pictures than the archive can show in public. “There are pictures shared with us by local fire fighters for example, but we do not have permission to go public with them.” I asked in return what the purpose of those nonsharable pictures was, to which he answered: “They are used only by researchers for their research purposes. There are many other pictures of the classified kind. People’s faces are what is not publicly archivable for the moment.” Likeness (or the ability to identify the faces of people captured by the images) has to be removed or obscured from the public gaze. Unlike the photo-cleaning volunteers for whom the preservation of faces was the royal road to the past disaster, for the academic effort to create the record of memories such icons became obstacles. “These are great pictures! I wish we could post them,” Shibayama said to me while running a workshop on the categorization of the photographs. The critical process in archiving the photographs, therefore, is to sort out what can go public and what cannot: whether a photograph shows people’s faces or not. To archive, then, is to downplay the photographic evidentiality of “the thing has been there” by removing faces from the gaze of viewers while maximally preserving the context of images: iconoclasm.

Many powerful academic recapitulations of the disaster present no face to be seen,Footnote 12 while a media archive, in particular, the NHK disaster archive’s web-based testimony documents rather seamlessly show the faces of survivors who agreed, for one reason or another, to be on TV.Footnote 13 The appearance of faces in archives like the one by NHK indicates society’s interest in seeing how the survivors are doing and what they have to say, while slowly but gradually parting from the images of the past in the tsunami-damaged photographs uncovered on the ground three years ago. Shibayma struggled with this ethical limbo during the above-mentioned workshop: “I think those photographs illustrating fukkō [reconstruction] activities [i.e., local festivals] should have faces. Otherwise, what are we showing?” The difference between an academic project and the national television program’s archive project is the need by the former to ask this very question. Moreover, the DAPs often depend on collecting photographs by asking for contributions from users who did not necessarily acquire any explicit consent from people captured in the photographs.

The academic project, supported by various funding agencies, cannot just report what is happening on the ground nor can it simply talk about the past as past or an object as object. It needs to generate a set of interpreted knowledge for a “better” future out of “objects of memory” (omoide no shina; Nakamura Reference Nakamura2012) by using the “raw” data, which include faces. Unlike many PRPs, such as the one I participated in as a volunteer, which have a clear goal of returning the objects of memory,Footnote 14 the DAP aims at sharing the photographs with as many people as possible. In this sense, the DAP’s classificatory process is doubly beneficial to scientists and researchers in that it both protects the right of likeness of ordinary people and provides academia with privileged access to the otherwise protected materials. Such privilege often goes unquestioned by way of the trick of representing the image as logic—that is, as being scientific—which is exactly how postwar Japan sought to prosper by attributing its loss to its inadequacy of scientific knowledge about the atomic bomb (Yuasa Reference Yuasa, Steineck and Clausius2013). In the historical context of Japan, science came to develop as a particular tradition that strongly bears the alchemic operation of transforming the past into a bright future, like transforming the loss of a war into a potential (technological) victory in the future. The scientific past is a subject of betterment.

The bottom line for the academic DAP’s efforts to understand the disasters is the following: whether there is a face or not, the ethos of shikatanai is not an acceptable moral principle for scientists and researchers alike. Geller’s critique regarding the earthquake prediction paradigm is not only a structural issue in the academic sphere but also an ethical constraint of science so conceived. The framing of past instances as lessons to be learned leads to the valorization of a register of likeness to that of contingency by removing the knowledge of the former in palimpsesting it with the latter. Thus, for the archive tradition, a set of photographs needs to be interpreted by experts first in order to talk about the future, because each photograph does talk about some aspect of the past: pars pro toto.

Rhetoric of the Photographic Records

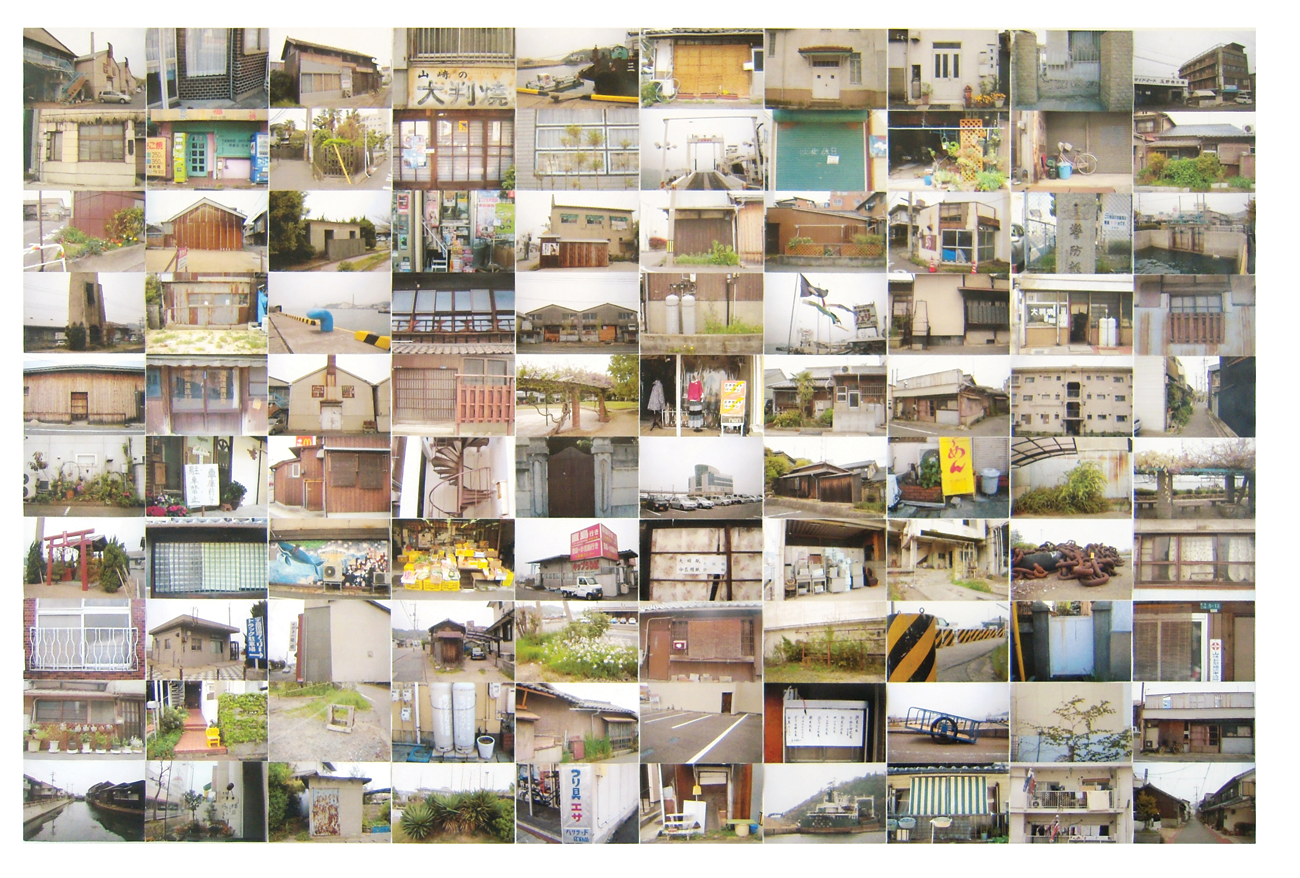

In the summer of 2012, Japanese artist Saburo Ōta put together an art exhibit in Tamano city, Okayama prefecture. The exhibit, called Driftcards, was a collage of photographs taken in the neighborhood of Tamano port in 2012 (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Driftcards 2012 by Saburo Ōta (http://aburakame.web.fc2.com/contents/exhibition/120701saburoota_unoport/driftcards.html). Courtesy of Artspace Aburakame.

Located over 600 miles away from the city of Sendai, Ōta’s Driftcards seemed to be matter out of place. What makes this set of photographs unique is Ōta’s visualization experiment: the artist manually soaked photographs he took of the port city in muddy water to simulate the impact a tsunami might have on the sights captured in the pictures. He describes his intention with the work accordingly:

According to the Tamano City Tsunami and High Water Hazard Map, it is expected that the Uno Ferry Terminal area will be flooded by at least one meter of floodwater; however, this is data from September 2007. My experienced local harbor contacts expect the water to rise at least five meters. In April 2012, I walked along the Tamano port. I photographed the sights of Tamano that I don’t want to lose. These Driftcard works (postcards swallowed by the tsunami) are my assumptions. The photos are ripped or warped in places from being soaked in muddy water [from the site].

Just like the many photographs publicly archived by Michinoku Shinrokuden, there are no faces to be seen in this artwork. Unlike the former, however, all of the portrayed buildings are intact, undamaged though slightly distorted by the water. Through this experiment, Ōta evokes a chronotope of the photographic image in which the object’s citation of the event of distanced time and space creates a “hyperreality” (Baudrillard Reference Baudrillard[1981] 1994) of the city’s damage from the simulated tsunami in the future. Simulation with images therefore is an act of citing both visible past and imagined future in an effort to let the photograph, whose orientation to the past is most visible, present more than it claims. Much like a filmographic representation, photographic simulation takes into account both presuppositions and creations, fiction and nonfiction. Such an act of signifying the photograph reveals the ethical/semiotic stance to the past by exposing the distance between the subject-object relationship: the subject’s relationship to the photographed past is scaled by the former’s act of representing the past.

For example, the iconoclastic digital archive produces a possibility for supra-individual simulations of reality that may be outside of one’s actual experience or beyond each photograph. In other words, at the cost of removing the presence of individuality, thus emphasizing the objectivity of each photograph, the digital archive tries to record an omnibus chronotopic memory of collectivity. Paradoxically, then, the goal of a digital archive is the production of yet another iconodule that worships not the idol but the “indexicalized” order of images, that is, the figure of images is reduced to the situation. The digital archive not only washes away hidden beliefs from images but also distances beliefs from actions by favoring post hoc interpretations over the object itself. The effect of digitalization, thus, is to erase the state-of-the-art claim of the photograph—the photographic presence—in order to schematize it. Such archived ideology circumnavigates the preexisting circulatory path of the photograph (see Silverstein Reference Silverstein2013) observed by Barthes, whereby people “consume images and no longer, like those of the past, beliefs” (Barthes Reference Barthes1981, 119).

This is exactly how the past is dealt with in the present by the iconoclastic DAP tradition. The past is significant so far as it is interpreted as offering lessons for the future to be learned in the present. This is the world where the photographs do not have a message but where each object is the token of a larger message, soaked with hidden subcultural presuppositions. The resulting photographic record foregrounds the epistemology of vision and fixates the eye to the subtly objectified happenstance. There is no longer a thing witnessed in each photograph, but the presupposed objectivity (re)presented by the selectively chosen image of the disaster in question.

This is the principal difference between kioku (memory) and kiroku (record) and between the PRP and DAP: differential matrices of the relationship between object, belief, and action, or what I have been calling the semiotic/ethical stance. There is no difference between memory and record as to the ontology of a photograph. Instead, there is a vast distance between the different ethos of action and pathos of belief about the photograph. The confusion between memory and record in the context of the 3.11 disasters in Japan, therefore, suggests the instability of the semiotic ground upon which particular understandings of the presupposed object-subject relationship emerge and compete (Morimoto Reference Morimoto2012). Different usages of disaster-related photographs by different subcultures illuminate this point. However, this struggle of interpretations between the two subcultures does not undermine the regimenting metasemiotic function of the object; the photograph is a historically contingent object representing some aspect of the past, and for this very reason the disaster-related photograph, in whatever form, is preserved.

Given this essential point, the ethnographic comparison between different interpretative traditions of the photograph suggests two important points. First, the fundamental rhetoric of the photograph is to make its referentiality partially relative, as in Rorschach’s inkblots (see Galison Reference Daston and Daston2008). The Barthesian photographic rhetoric of “the thing has been there” is elaborated by a particular cultural belief about the pathos of the photograph rather than the nature of the photograph itself. This can be illustrated by observing a particular usage of the photograph in relationship to what is actually being claimed through the object itself. The two photographic laboratories in discussion were able to work with different types of photographs as the same object of past memory, while making different claims about their specific interpreted responsibility to the past. The multiplicity of response was possible only insofar as there was the implicit convention that the photographic object stood for some past and that it calls for some action. Ōta’s experimental piece supports this claim, although as a violation of the rule. He used a series of photographs to refer to a kind of future imagined after 3.11 in which a similarly devastating tsunami is prophesied to occur in a different part of the country. However, this rare case of the usage of the photograph interrupts the well-accepted cultural meaning of the photograph as the object of memory by claiming the photograph’s ability to prophesy a future, and therefore the piece did not beget much following action about the object. Ōta’s “inappropriate” usage of the object reflected, on the one hand, the ineffectiveness of his claim due to his violation of the convention and, on the other hand, the openness of the photographic object, which allows various referential potentials in its citation, although they are regimented in their function. The photograph is, underneath its historical, sociocultural, and political motivation, never an evidential claim or an alibi in and of itself but rather a free-floating object that is presented to people who in turn represent it.

The photograph, as a presentational vehicle, seems to have a special quality. Munn (Reference Munn1986), following Peirce, calls this special attribute of an object in society a “qualisign,” summarized by Keane as “certain sensuous qualities of objects that have a privileged role within a larger system of value” (Reference Keane2003, 414; cited in Manning Reference Manning2012, 12). As a hybrid of both an objectified record of a personal history and a new memory evoked in the present by the observer, disaster-related photographs are one example testifying that we not only order a world of objects (record), but also that objects order our world (memory) (Miller Reference Miller and Ingold2002). This article adds to this observation by suggesting that the same object with different modalities can be used equally as the legitimate alibi to achieve a collective end by different subcultures, and depending on the semiotic stance of a subculture under analysis, the same object can and does differently order the world and us.

This observation leads me to a second point. Because the photograph serves as the site of interpretations for its signification, the more conventionalized the meaning of an object is, the more presupposed its associated action and belief are to a group of people under analysis. For instance, neither of the subcultures ever questioned the photographic technology that produced the photograph itself, nor did they speak their various views toward ways in which each photograph might have been produced. For them, the photograph undoubtedly stood for some aspect of reality regardless of how it was produced. Therefore, in this context, a highly cultural semiotic relationship between subject and object is maximally transparent in that any discourse about it meets with some dull response, if not silence, from the informant. This speaks to Silverstein’s (Reference Silverstein and Duranti2001) poignant point that the “limit of awareness” of the “natives” of a culture may present highly coded practice as arbitrary and conventional when, after analysis, it reveals itself to be a confabulated web of sociohistorically ordered indexicalities or a matrix of beliefs and actions. In this sense, much cultural knowledge haps follows the concept of what Galison (Reference Galison2004, 237) calls “anti-epistemology” or “the art of nontransmission,” working to cover and obscure a code of decipherment.

In an effort to identify the space between thing-in-itself and objectified thing, Barthes (Reference Barthes1981) identified that photography has no futurity in and of itself. This temporal constraint requires people to attribute futurity to the photographic object. The photograph is resurrected in the present when it is recontextualized or “cited” (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2012). Equally, the photograph as “a perfect analogon” of the event of photographing necessitates the presupposed order, perspectives, scales, and so on, of things in the world to be shared within a particular tradition. In order for the photograph to have a message in the present, the photographic scene has to be reanimated so as to move beyond its spatial-temporal constraints. The PRP’s narrative reconstruction of the photographed woman via a series of re-collected photographs speaks to this reanimation process. In contrast, the DAP’s ethical obligation to hide faces challenges the archive in representing its implicit categorization of reconstruction as people’s activities. The photographic object in the postdisaster contexts is a powerful communicative tool because, first and foremost, it suggests a possibility of a sharable or tradable (extra)linguistic field of perception that can be interpreted in various manners, on the one hand, and, on the other, the photograph’s prevalent objective claim of the presence of its content in a particular space and time in some past.

This leads to my key point: the photograph is by its nature antisemiotic in that it resists interpretation unless its visual persuasion is domesticated by “ethnometapragmatics” (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Clyde, Hanks and Hofbauer1979, 207), that is, the cultural talk about the sociocultural, political, and historical significance of the image or a set of images. However, the usage of a photograph is always already semiotic because no past can be perfectly reproduced in the present. Both the iconodule and iconoclastic traditions described in the article find this equifinality in their particular ordering of the photographs; the photographs have to be translated into signs. If we take the position that the object itself has a message (Daston Reference Daston and Daston2008), then “the possibility of lying,” according to Eco, “is the proprium of semiosis [sign-process]” (Reference Eco1976, 58). In the coming-into-being of the photographic record, that is, in equating the photographic object as the signs of the past event, lies the Rorschach test of culture. Investigation into the usage of a photograph—the act of (re)citing the past in the present—invites an analysis into an entailment of a cultural apperception of collective experience (Galison Reference Galison and Daston2008).

In this selectively visible purview of culture, the disaster-related photograph is the perfect ambiguous sign; the photograph simultaneously stands for memory and record insofar as it evokes people’s duty toward the past and the dead. The photograph is a “possible method to delay the moment [of accepting death]” (Takahashi Reference Takahashi2014, 132). Therefore, it can be easy and yet difficult to talk about the photograph (see Maekawa Reference Maekawa2008, 107). Within this very objectifiable object people hailing from different traditions have been trying to find traces of the past and clues for the future. Whether such traces and clues are discovered by the principle of resemblance or contiguity, the resulting order of things and people finds its origin anchored in an aggregation of a vanishing object and an emergent subjectivity, a culturally specific semiotic stance that is a trading zone, a zone where any effective representation of an object is made possible.

Conclusion

Disaster destroys, yet it also unearths a “sign-fication” of material objects, which come to embody a certain matrix of belief and action in their (re)presentation and various semiotic stances in their usage. An anthropology of disaster could trace emerging techniques of the object to retrieve disaster and its anti-epistemological classification process, while carefully demarcating the object from its representation or sign. This article shows the intersection between object and subject in the two subcultures’ tacit tagging of kioku (memory) and kiroku (record) as a part of their usage of disaster-related photographs. The struggle over memories is no longer between various meanings of the object, since no object is ever raw when observed from any scale and perspective. Instead, it is what is beneath the object’s claimed flawless presence—its rhetoric—that clearly and distinctly presents evidence of a codified message that has no coda.