No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 May 2017

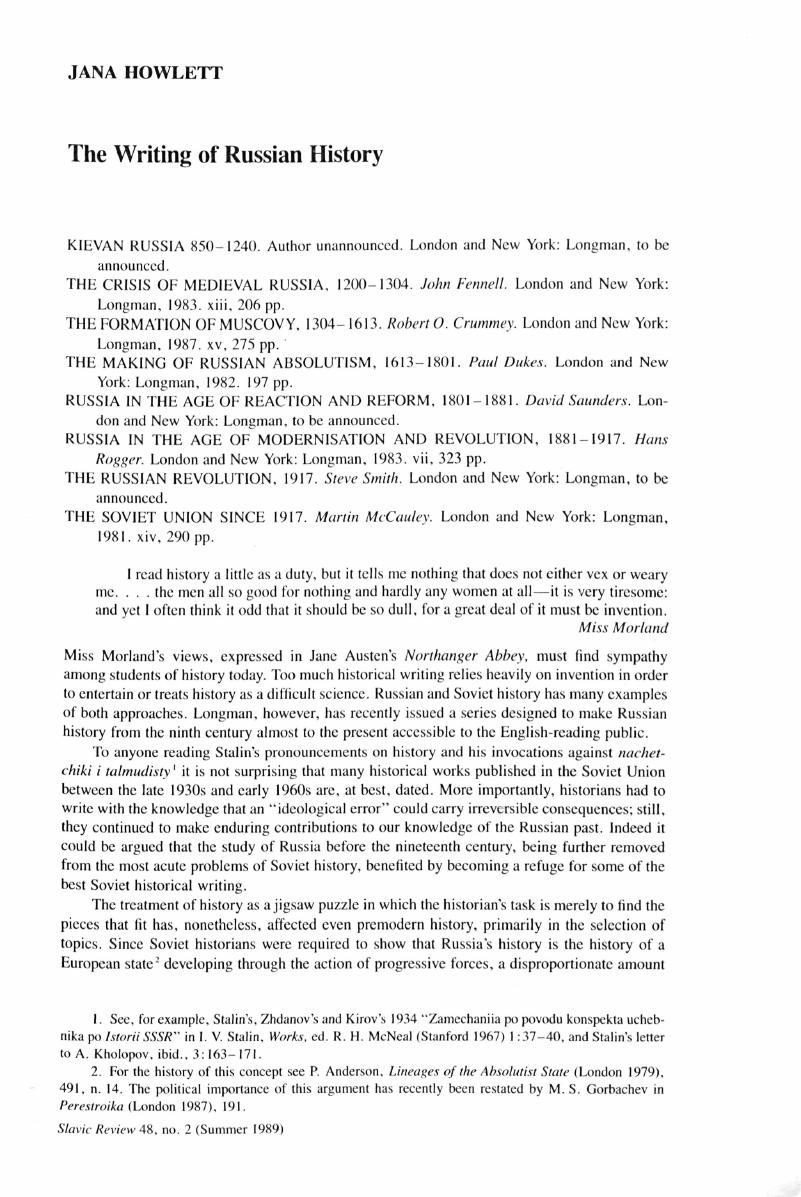

1. Sec, for example, Stalin's, Zhdanov's and Kirov's 1934 “Zamcchaniia po povodu konspekta uchebnika po Istorii SSSR” in I. V. Stalin, Works, cd. R. H. McNeal (Stanford 1967) 1 :37–40, and Stalin's letter to A. Kholopov, ibid., 3:163–171.

2. For the history of this concept see Anderson, P., Lineages of the Absolutist Stale (London 1979), 491, n. 14Google Scholar. The political importance of this argument has recently been restated by M. S. Gorbachev in Perestroika (London 1987), 191.

3. Recent articles by M. B. Sverdlov, V. I. Goremykina, and A. lu. Dvornichenko in Voprosy Istorii, 1985, no. 11 and 1987, no. 2 and no. 6 show that this often circular debate is alive and kicking.

4. Pipes, R., Russia under the Old Regime (London, 1974). 57 Google Scholar. For a more balanced view see Halperin, C. J., Russia and the Golden Horde (Bloomington, Ind., 1985)Google Scholar.

5. Anderson, P., Lineages of the Absolutist Stale and Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism (London, 1974)Google Scholar.

6. Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist Stale, 201, 330. The ideology of translatio imperii was known in Russia, but in the fifteenth century it was used by the church to claim translatiopotestas and rights in relation to the state.

7. The two volumes dealing with the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have needed an annual reprint.

8. Compare the description of the events of 1203 in Fennell's work (pp. 26–27) and in the chronicle he cites (Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisei 1: cols. 418–419.

9. See, for example I. P. Shaskol'skii, Bor'ba Rusi proliv krestonosnoi agressii nu beregakh Balliki v XII-XIII vv. (Moscow, 1978). Chapters 2 and 3 of John Meyendorff's Byzantium and the Rise of Russia (Cambridge, U.K., 1981), discuss the reasons behind the church's support for Aleksandr.

10. Crummey, The Formation of Muscovy, 189.

11. Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist Slate, 212.

12. Dukes, Making of Russian Absolutism, 141.

13. In addition to the books cited by Dukes, see also Dokumeniy stavki E. I. Pugacheva, povslanicheskikh vlastei i uchrezhdenii, ed. R. V. Ovchinnikov et al. (Moscow 1975), and V. I. Buganov, Pugachev (Moscow 1984). Buganov's book is aimed at the general reader, yet draws on a wide range of sources. A departure in Soviet historiography, this work presents Pugachev's rebellion as a revolt at least partly based on conservative sentiments with a moving force arising as a protest against the lot not only of serfs, but also of Russia's subject nationalities in the south.

14. Fennell, The Crisis, 5, 57.

15. The adjective nominal may be used here in the specialist sense of nominal wages, i.e., wages measured in money rather than purchasing power, but to most readers it would suggest the more common meaning— insignificant.

16. The only omission I noted in this context was the story of the Zinoviev letter, important in a book that otherwise fulfills the series’ aim of describing the role of Russia in its wider European context.

17. Westwood, J. N., Endurance and Endeavour: Russian History 1812, 2nd ed. (Oxford 1981)Google Scholar; Hosking, G., A History of the Soviet Union (London 1985)Google Scholar.