Introduction

Mass warfare created a huge demand for social protection, pushing governments to provide income for invalids, war victims, and the survivors of fallen soldiers (Castles Reference Castles2010; Obinger et al. Reference Obinger, Petersen and Starke, eds.2018; Rehm Reference Rehm2016; Schmitt Reference Schmitt2020a, Reference Schmitt2020b). Warfare, together with the tremendous pressures generated by long-lasting, war-related social problems, led to the adoption and reform of numerous social policies throughout much of the Global North (Obinger et al. Reference Obinger, Petersen and Starke, eds.2018). Most European colonial powers, including France and Great Britain, recruited soldiers, and other security forces not only from their metropoles but also from their colonies during both World Wars. However, existing research on warfare in former colonies from historians focuses on the recruitment of colonial soldiers (e.g., Antier Reference Antier2008; Echenberg Reference Echenberg1991; Ekoko Reference Ekoko1979; Killingray Reference Killingray1979; Koller Reference Koller2008; Michel Reference Michel1973; Strachan Reference Strachan2004), with only passing attention paid to the influence of warfare on social reforms. Instead, this literature focuses on the underlying colonial strategies, imperial military objectives, and the instruments employed to achieve them in colonies, revealing differences between British and French colonial powers. France heavily pushed for the militarization of colonial societies around World War I (WWI) and even introduced universal male conscription in French West Africa in 1919 (Buell Reference Buell1965: 10; Conklin Reference Conklin1997). In contrast, Britain took a more decentralized approach toward security in its dependent territories in Africa, where each colony was responsible for its own internal security and with its ports protected by Britain’s unparalleled naval power (Killingray Reference Killingray1979).

Against this background, we explore the implications of warfare for social reforms in the former French and British colonies of West Africa until the post-war period of WWI (Schmitt Reference Schmitt2020c). This comparative, exploratory research design is focused intentionally on the contiguous subregion of West Africa, which differs with respect to French and British colonial and militarization strategies but otherwise exemplifies highly similar conditions during this time period (McLean Reference McLean2004). To identify linkages between warfare and welfare in British and French colonies of West Africa, we reviewed and synthesized data from primary sources (e.g., historical documents from British and French National Archives) and secondary literature. This review explores the implications of warfare for social reforms in West African colonies of the British and French Empires, respectively. In so doing, this paper is a first step toward better understanding the relationship between warfare and welfare in a colonial context to inform future studies that further specify and test causal chains and mechanisms at this nexus. Understanding the warfare–welfare nexus in global context is also critical in order to correct for Eurocentrism in political economy and welfare state research (Bhambra Reference Bhambra2021) and to widen and deepen our understanding of social policy trajectories in the Global South, particularly in territories classified as insecurity regimes (Wood and Gough Reference Wood and Gough2006).

We show that the form and nature of the warfare–welfare nexus was influenced by the colonial and military strategies of the colonizing power and the instruments used to implement them. While Britain and France had similar overarching imperial objectives in West Africa of securing their colonies, enforcing order within them, and promoting commerce to increase both metropolitan profits and colonial revenues, they went about achieving them very differently, with consequences for social reforms (or the lack thereof). The formal introduction of conscription in French West Africa and the military service of indigenous populations in European theaters ultimately opened the door to gains in social protection post-conflict, both directly in the form of social policies and indirectly through exposure to forms of resistance, such as strikes, as well as Western justifications for receipt of social protection, such as notions of citizenship and rights. In contrast, in British colonies of West Africa, the indigenous populations who served during WWI saw few, if any gains in formal social protection after the conflict. The lack of integration of indigenous soldiers with British troops and their absence in Europe did nothing to increase their exposure to Western ideas of rights and citizenship. Furthermore, the fact that most indigenous servicemen were porters, who carried food stuffs, weapons, and other essential equipment, rather than soldiers engaged in direct combat, inhibited social recognition of indigenous servicemen as war veterans.

By way of outline, the paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, the paper discusses militarization before and during WWI in French and British colonies of West Africa. Then, in the third section, the paper illustrates the warfare–welfare nexus in French and British colonies of West Africa, respectively. In the fourth section, the paper discusses the implications of warfare on social reforms in West Africa across the empires to draw out critical similarities and differences before considering ways in which the warfare–welfare nexus differs in a colonial context.

The militarization of British and French colonies of West Africa

Militarization in French West African colonies

Militarization before WWI

French military policy in their West African colonies can be dated back to 1857, when the first regiments of the Tirailleurs Sénégalais (Senegalese Rifles) were founded. Over time, Senegalese Rifles became “the generic term for Black African soldiers in the French colonial army” (Echenberg Reference Echenberg1975: 174), and they were mainly established to extend France’s political control across West Africa (Echenberg Reference Echenberg1975: 172; Ginio Reference Ginio2017: 3). For a standing specialized army of battalion strength, the Senegalese Rifles were very limited in size. For example, in 1890, the overall number of Senegalese Rifles was only 3,000.

It was not until the Afrique-Occidental française (AOF, or the French West African Federation) was created in 1895 that the nature and size of French forces in West Africa were modified and transformed. The formation of the first French West African government in 1905 established a basic colonial order and regional administrative structure. It also signaled the end of military conquest and a shift to civilian rule in the region. From 1905 onward, the main objectives of French colonial strategy were to maintain the colonial order and promote commerce. France therefore extended the deployment of the Senegalese Rifles and used their battalions to defend the French Empire and to preserve political order and control over its territories (Echenberg Reference Echenberg1991: 28; Huillery Reference Huillery2014). When forming the AOF, French officials soon determined that more soldiers were required to maintain order than to establish political control. Subsequently, voluntary recruitment was considered to be insufficient to levy enough soldiers, especially since the army competed with the economy for abled-bodied men. As a result, discussions on introducing conscription in French West African colonies were initiated.

In 1904, a decree was introduced that took a first step toward conscription in the case of insufficient volunteers (Buell Reference Buell1965: 5). Three years later, this was followed by a decision to build a commission to evaluate possibilities for introducing universal conscription in African colonies and to obtain an estimate of the number of soldiers required. The commission was headed by General Charles Mangin, a well-known and influential general who had investigated the possibilities for conscription in North Africa (ibid.: 5). General Mangin developed a clear vision of creating a Black army and was one of the most enthusiastic proponents of an African army. In his book La Force noire, published in 1910, he stated that falling birth rates in France made it necessary to use African soldiers not only for the defense of the Empire in overseas territories, but also for the defense of the motherland, declaring that Black troops would constitute an important factor in a European war (Mangin Reference Mangin2011: chap. 1–2).

Even though Mangin himself favored the creation of a professional army, the French Parliament passed a decree in February 1912 based on his findings that only enabled and authorized conscription in French West Africa, Algeria, and Tunisia (but not in Morocco) if the numbers of volunteers were considered to be too low (Koller Reference Koller2008: 115), which was in line with the view of William Ponty, Governor-General of the AOF. The decision to pass this decree and therefore to rely increasingly on Black troops was reinforced by the fear of French politicians and military officials of a shrinking population in the motherland, in light of decreasing birth rates in combination with the need for soldiers. French officials were afraid that Germany’s dominance and the depopulation of France might result in a military advantage for the German army (Dörr Reference Dörr2020; Echenberg, Reference Echenberg1975: 179). Therefore, integrating Black soldiers into the French military was seen as an instrument both to save French soldiers’ lives and to realize military and demographic policy goals. However, this recruitment policy was far from uncontroversial. Several members of the General Staff expressed reservations about the military value of African soldiers serving in Europe in terms of physical and mental fitness (Conklin Reference Conklin1997: 144; Lunn Reference Lunn1999). Nevertheless, on the eve of WWI in 1914, the recruitment of Africans increased from four to ten percent of the adult male population in French West Africa (Conklin Reference Conklin1997: 143).

Eventually, the proponents of conscription prevailed against the backdrop of the destruction of WWI. Under the policy, males between the ages of 20 and 28 could be conscripted for a term of four years. Although conscription was intended to be voluntarily, compulsory enlistments were introduced in practice. Local chiefs were given a quota of potential conscripts that they had to present to a commission de recrutement for medical inspection and enrollment.

Militarization during WWI

A further expansion of recruitment efforts was discussed in the light of the enormous losses of French soldiers during WWI (Andrew and Kanya-Forstner Reference Andrew and Kanya-Forstner1978: 14). The French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, who was initially very skeptical about the value of African soldiers in conflict, was increasingly influenced by colonialists, especially in the second half of WWI when France needed more soldiers. For example, Charles Jonnart, the president of the Comité de l’Afrique Francaise, and especially Blaise Diagne, a Senegalese politician and the first Black person in the French National Assembly, persuaded Clemenceau that recruiting Black Africans helped to compensate for the massive losses of (white) French African soldiers (ibid.: 14). Clemenceau therefore initiated a massive recruitment campaign in 1917. He ordered a large levy and instructed Blaise Diagne to implement it. Blaise Diagne, who had the trust and respect of many French West Africans, was very successful in recruiting colonial subjects and achieved the fulfillment of the new levy without large resistance.

During WWI, a total of 845,000 soldiers indigenous to the colonies served in the French Army (including from North Africa, French West Africa but also Indochina, cf. Buell Reference Buell1965: 10). From French West Africa, 170,891 soldiers were sent to the military forces (Ginio Reference Ginio2017: 6). They were deployed mainly on the Western front and were involved in all major battles at the Marne, the Yser, the Somme, and Verdun (Koller Reference Koller2008: 119). They formed part of the Gallipoli operation, fought in the Balkans, and were involved in the occupation of the Rhineland after WWI (Scheck Reference Scheck, Zeiler and DuBois2012: 503). While, in the beginning, Black troops were often segregated into separate battalions, they were more and more deployed in regiments consisting of both Senegalese and European soldiers in the course of WWI (Lunn Reference Lunn1999: 20).

Against the background of the huge losses of manpower in France and the need for demobilizing French soldiers to build up the economy back home, colonial troops and African soldiers remained largely mobilized after WWI. In the light of Diagne’s success in recruiting African soldiers, Clemenceau decided to maintain conscription in peacetime (Conklin Reference Conklin1997). Universal peacetime conscription was introduced in French African colonies in 1919 and conscripts had to serve three years (Buell Reference Buell1965: 10). This was a further landmark with regard to the militarization of colonies.

Figure 1 illustrates the increase in recruiting soldiers in tropical Africa from the late nineteenth century until the end of WWI. At the height of WWI, around 180,000 soldiers from French West Africa were deployed. In the end, WWI marked the transformation of the French Black army and the Senegalese Rifles into a mass army.

Figure 1. Number of Tirailleurs Sénégalais.

Notes: Data on total number of conscripts has been extracted from Echenberg (Reference Echenberg1991: 26); please note that data has been available for the years 1890, 1900, 1910, 1912, 1913, and 1918.

In sum, the militarization of French West Africa mainly took place from 1905 to 1919, when peacetime universal conscription was introduced. During this period, the French West African army was transformed into a mass army. It is estimated that 200,000 Africans were eventually mobilized between 1912 and 1919 (Conklin Reference Conklin1997: 143). Even though there is still a debate among historians about the number of deaths of Africans during WWI, a conservative estimate of the death rate in relation to the mobilized is at least as high as for French soldiers from the metropole, that is, on average around 22% (Echenberg Reference Echenberg1975: 364; Lunn Reference Lunn1999: 532). The death rate of African soldiers is reported to have been exceptionally high in the later periods of WWI, reaching as high as 39% in 1918 (Lunn Reference Lunn1999: 33). The extent to which the society in French West Africa was militarized during and after WWI and the set of recruitment instruments applied by France (most famously the introduction of compulsory peacetime conscription) is unique across empires. In contrast to other European powers, the African troops from French colonies were deployed also in Europe and were at least partly integrated with regular French troops (Conklin Reference Conklin1997: 143; Lunn Reference Lunn1999: 527).

Militarization in British colonies of West Africa

Militarization before WWI

Unlike the French, who formally adopted conscription as a recruitment policy to accomplish the twin goals of preventing depopulation in France and realizing military goals (Killingray Reference Killingray1979: 422; Schmitt Reference Schmitt2020c: 220), the British never fully committed to the idea of creating an imperial African army before, during, or after WWI. Instead, the British used their naval power to secure key ports and relied on alliances with leaders of indigenous populations to secure inland territory, which allowed them to reinforce their position that African armies should not be used to fight “white men’s wars” (Killingray Reference Killingray1979: 422). This policy was justified by purported concerns about the reliability of African troops and grew out of fear that arming and training indigenous populations might fuel resistance and threaten British colonial rule, not least because, “allowing Africans to kill Europeans would expose the bluff that made British rule in Africa possible” (Parsons Reference Parsons2015: 184; Killingray Reference Killingray1979). Additionally, any suggestion that African armies could be used in such a capacity drew opposition from anti-imperial lobbyists and humanitarians throughout the Empire (Killingray Reference Killingray1979: 423). From an administrative view, Britain’s War Office and Colonial Office were relatively siloed operations after their division in 1854, and there was “no provision of a military department with the Colonial Office nor was there a department for colonial warfare at the War Office” (Ekoko Reference Ekoko1979: 47). Moreover, Britain withdrew military forces in its self-governing dominions from 1870 to 1871, and by the turn of the century, these territories were recognized as having the capacity to support Britain in any conflict that did not pose a threat to them directly (Gordon Reference Gordon1962). In this context and in line with its policy that British colonies should be self-sufficient, Britain assumed a laissez-faire stance regarding colonial defense policy, with only a Colonial Defense Committee at the Colonial Office to provide technical advice and review of colonial defense strategies, in addition to which “various constabularies and Frontier Police forces dotted British possessions” (Ekoko Reference Ekoko1979: 48; Gordon, Reference Gordon1962).

Defense planning in British colonies of West Africa in the event of a European conflict only began in earnest in the 1890s. Given the need for colonial powers to demonstrate an “effective occupation” of colonial territories after the Berlin Conference in 1884, it became apparent that Britain’s reliance on diplomacy and naval power to defend its territories was insufficient. As a result, a number of constabularies, including the Royal Niger Company’s Constabulary and the Niger Coast Constabulary (also known as the Oil Rivers Irregular Force), were established and strengthened to ensure that Britain was ready and able to defend and advance its territorial claims and interests in West Africa (Ekoko Reference Ekoko1984-5: 64). In response both to reports from the Colonial Defense Committee highlighting inland security concerns in the hinterlands of the Gold Coast and Lagos Colony and to Prime Minister Lord Salisbury’s general opposition to the deployment of British troops to the colonies, the West African Frontier Force (WAFF) was created in 1898 with funding from Her Majesty’s (HM) Treasury. The WAFF was led by Sir Frederick Lugard, who had experience both in military conflicts throughout the Empire as well as with the Royal Niger Company, and it became a key British instrument of imperial policy in the region both before and during WWI (Ukpabi Reference Ukpabi1964).

After the initial creation of the WAFF, it became clear that this force alone would be insufficient in the event of a conflict between empires. To address this, both reserves and companies of volunteers were created within British colonies. The policy to create reserves was first indicated in a circular from the Colonial Office to relevant colonial governors in 1904 (Ekoko Reference Ekoko1984-5: 57). From the outset, it was recognized that non-European recruits were often relegated to lesser tasks in military service, leaving them little claim to the spoils of warfare. To address this inequity, it was envisioned that the reserve could take on these lesser tasks in the event of a conflict, allowing non-European recruits to participate in combat, thereby entitling them to benefits such as free land and/or exemption from hut taxes after any conflict (ibid.: 57). However, the reservist policy received mixed reviews from colonial governors, ranging from proactive implementation of the scheme in the Gold Coast to strong resistance and opposition from Lugard in Northern Nigeria.

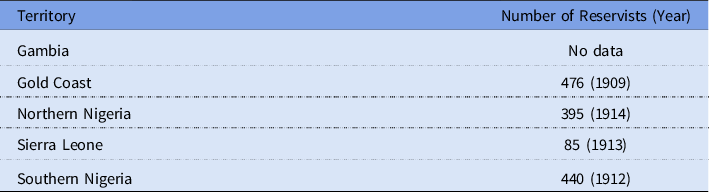

Nevertheless, reserve forces were eventually created in West Africa, as indicated in Table 1, with the Gold Coast showing the strongest implementation of the policy early on by a substantial margin, particularly given its relatively small population compared to Northern and Southern Nigeria. The positions held within British reserve units were determined largely based on class, as well as ethnicity. To structure these forces, the British adopted “a policy of ‘racial’ diversification” to promote “internal political stability” and minimize “the risk should one ethnic or religious group take advantage of their numerical superiority against the British” (ibid.: 56).

Table 1. Number of reservists in British colonies in West Africa before WWI

Source: Ekoko (Reference Ekoko1984-5: 59).

In the end, it was estimated that British troops in West Africa (including the WAFF, reservists, volunteers, and other police forces) before 1914 totalled 12,469 (Ekoko Reference Ekoko1984-5: 60). The WAFF accounted for at least 7,560 (61%) of the troops in the region, with reservists/other police forces and volunteers accounting for approximately 31% and 8%, respectively (ibid.: 60). The WAFF was comprised of 244 British Officers (3%), 115 non-commissioned offers (2%), and 7,201 African troops (95%). Furthermore, approximately 5,000 of the WAFF’s African troops originated from Nigeria, and approximately 80% of these troops were Hausa and Yoruba (Njung Reference Njung2019: 52).

Militarization during WWI

As originally envisioned, recruitment beyond the metropole in the British Empire during WWI took place predominantly in the dominions. Until the introduction of conscription in the United Kingdom, Britain recruited on a voluntary basis throughout its Empire. As before the conflict, British belief in the inferiority of colonial subjects made it difficult to suggest that they should shoulder state duties on a par with those of British citizens. In 1917, the Colonial Office rejected proposals from the War Office and some colonial governors to institute conscription in African colonies (Parsons Reference Parsons2015: 187), and the policy was never introduced. Furthermore, unlike the French, the British did not bring African troops to fight in European theaters (Koller Reference Koller2008: 114). In the end, over 95% of the British forces involved in WWI from beyond the United Kingdom were from the dominions, with less than 5% from British colonies. From this <5%, it is estimated that approximately 25–30,000 (∼1%) soldiers were from West Africa (Parsons Reference Parsons2015: 200; Strachan Reference Strachan2004: 4) and that as many as 20,000 soldiers were from Nigeria, due both to its close proximity to Cameroon, a former German colony, and its relatively large population (Njung Reference Njung2019: 49, 52).

While the official number of soldiers from non-dominion colonies were few, a total of over one million Africans were “voluntarily” mobilized to support the British War effort in Africa, with some participating in direct combat and most serving as military porters, more commonly referred to then as carriers (Parsons Reference Parsons2015: 183). In the absence of both large numbers of motorized vehicles and available pack animals to assist with transport due to tropical diseases, such as trypanosomiasis (ibid.: 188), carriers were essential to British military engagements in Africa throughout WWI. Similar to the French, British field administrators leaned on local clients and leaders of indigenous tribes to provide men for military service, establishing quotas that were usually met in exchange for money and other honors before resorting to more coercive measures (ibid.: 187–8). Therefore, in practice, the British recruited servicemen in numbers comparable to the French during WWI, and these servicemen were, for all intents and purposes, forced to support the attainment of British military objectives under the guise of “voluntary” service.

Mortality rates for African soldiers and other servicemen, including carriers, were disproportionately high. For soldiers, this was often the result of lesser and poorer training as well as less experience (Njung Reference Njung2019: 53). For both soldiers and “voluntary” servicemen, disease and lack of sanitation proved more deadly than the conflict itself, and conditions were particularly deadly for indigenous carriers. Carriers died in great numbers during WWI, not least because “colonial military officers… believed that native tribesmen needed less food and could endure greater hardship than European troops” (Parsons Reference Parsons2015: 189). In response, “Nigeria experienced a wave of recruiting riots in the southern half of the colony in the early years of the war that police and military forces put down with considerable loss of civilian life” (ibid.: 189), and indigenous populations affected by conscription policies in French West Africa and the rest of the continent also resisted (Killingray Reference Killingray1989: 490; Koller Reference Koller2008: 115). “The head of the Military Labour Service, the office responsible for carrier welfare, tried to enforce regulations regarding rations and working conditions, but as a mere lieutenant colonel he had no authority to issue directives to field commanders” (Parsons Reference Parsons2015: 195). As a result, the death rate among African carriers was over 20% (Killingray Reference Killingray1989: 493).

In sum, the British did not rely on African forces in European theaters and did not formally introduce conscription in African colonies during WWI. The formal introduction of conscription was, in many ways, unnecessary from a functional perspective, as legal and administrative systems to support the informal recruitment of forced labor via chiefs and headmen were already well established throughout British colonies of West Africa. As detailed by Killingray (Reference Killingray1989: 488–9):

“The Gold Coast government passed the Compulsory Labour Ordinance, under which several thousand men and women found themselves dragooned into carrying for the military. In Southern Nigeria, the forced labour provisions of the Native House Rule Ordinance (1901) and the Roads and Creeks Proclamation (1903) squeezed labour for the military campaigns to subjugate the eastern Niger region”

In other words, distinctions between peace and wartime economies were far less meaningful in territories that had been annexed, occupied, and colonized to various degrees. In the context of an extensive history of slavery and ongoing forced labor, establishing systems to recruit manpower to support colonial military objectives would have been nothing more than reinventing the wheel that had long provided labor to mines, farms, and colonial public works projects. Furthermore, in the absence of problems recruiting labor to meet either military or economic objectives and with few demographic concerns in the context of its dominions, there appeared to be no strategic benefit or incentive for the British to formally adopt a conscription policy. If anything, formal adoption of such a policy ran the risk of damaging Britain’s carefully and strategically crafted global image as a philanthropic hegemon.

The Great War and the warfare–welfare nexus in British and French colonies of West Africa

The warfare–welfare nexus in French West African colonies

Direct implications for social reforms

What consequences did the militarization of French West Africa have on social policies and reforms? One consequence of the recruitment policies was that French officials began to realize that relying heavily on French African soldiers and their military service needed to be compensated at least to some extent. This insight was closely linked to the success of Blaise Diagne’s recruitment efforts. Diagne recognized African military service as an opportunity to consolidate the rights of the African French early on. He declared that “the war, despite its horror…has become for the people of Senegal an important instrument of social reform” (Gamble Reference Gamble2017: 57). As commissaire de la République, he negotiated a series of concessions from the Clemenceau government for war veterans and their families before agreeing to lead recruitment efforts in the AOF (ibid.: 59). Additionally, to support the families of conscripts, Diagne secured for war veterans (at least on paper) a specific salary and a state pension after the war (Summers and Johnson Reference Summers and Johnson1978: 29). Even though the Senegalese Rifles were technically eligible to receive a state pension, this was contingent on 25 years of service, which was often far too long to ensure a benefit in practice. This condition was relaxed in 1904 when a second decree allowed a proportional pension after 15 years of service (Echenberg Reference Echenberg1991: 24). Even still, only a very minor share of all soldiers received a pension before WWI. Moreover, Diagne negotiated that war veterans were at least partially exempted from the Code de l’Indigénat. Footnote 1 For example, in French West Africa, the extension of conscription to the Quatre communes of Senegal was followed in 1915 by a formal recognition of the French citizenship of the originaires Footnote 2 (Andrew and Kanya-Forstner Reference Andrew and Kanya-Forstner1978: 17). The Extentending the right to obtain citizenship to all indigenous soldiers was even discussed in 1915. However, this did not become official policy and reforms were relatively minimal. Perhaps more importantly, the French debated legitimated demands for social reforms and their implementation.

One problem that became apparent during the massive recruitment efforts was the physical condition of many potential soldiers, resulting in a debate on expanding health services. The majority of indigenous conscripts presented to French recruiting commissions or mobile drafting boards by chiefs were classified as physically unfit for military service. In some districts, only 10% of the potential conscripts were deemed physically fit enough to serve (Buell Reference Buell1965: 13). In consequence, Albert Sarraut, Minister of Colonies, stated: “Medical aid is our most immediate and matter-of-fact interest” (Sarraut Reference Sarraut1923: 94). Therefore, French officials aimed to extend health and medical infrastructure and services, which were originally established for French troops in the colonies, to indigenous populations.

However, extending health services to indigenous populations was very difficult in practice. One major problem was the lack of medical staff and doctors. At the beginning, the medical staff consisted mainly of Europeans. However, the number of European doctors and other medical personnel was not sufficient to realize an expansion of services to indigenous populations. Therefore, medical schools were built, and Africans were trained to be assistant doctors to counter the health problems leading to high unsuitability rates for military service. The most prominent medical school was established in 1918 in Dakar to train Africans as auxiliary doctors, midwives, and pharmacists to expand the provision of primary and preventive care (Lasker Reference Lasker1977). In sum, colonial military health services served as the foundation of what became civil medical health services in French West Africa.

In addition to medical schools, professional, as well as primary and secondary schools were created (Gamble Reference Gamble2017: 59). Diagne not only negotiated salaries and social, as well as political rights for veterans and their families but also obtained formal assurance of opening new professional schools, as well as a full lycée as compensation for the contribution of Africans to the war (ibid.: 59). When justifying the creation of the lycée in 1919, Henry Simon, Minister of the Colonies, stated that:

“After the heroic sacrifices made by the populations of West Africa for the defence of France, the moment has come to respond to the wish of these populations, expressed particularly forcefully in recent years, to be equal to our most favoured colonies when it comes to public education. It is appropriate to begin this work by founding a lycée” (ibid.: 194)

And then later, Sarraut wrote to the French president that:

“The inauguration of a new institution of intellectual progress must appear as a symbol and a form of gratitude that France shows the sons of her colonies for their participation in the victory.” (ibid.: 195)

Additionally, schools for future African officers and soldiers and their sons were established such as the École Spéciale des Sous-Officiers Indigènes in 1921 (Echenberg Reference Echenberg1991: 66). Furthermore, special primary schools were established in the 1920s, called Écoles des Enfants de Troupe (EETs) as an instrument of giving special opportunities to the sons of active soldiers and veterans who had priority access to these schools (ibid.: 66). However, the education level was low at EETs, and the main objective of creating African sergeants and military personnel was more functional than intellectual. French officials also used the provision of education to improve the image of being a colonial soldier serving France, and they launched propaganda campaigns to levy the greatest possible number of indigenous peoples under the tricolor. After military service, they promised colonial conscripts that they would return to civilian life “better educated, better disciplined, knowing our language better and more fit consequently for all kinds of work” (Buell Reference Buell1965: 11).

The growing importance of education and health services also led to the establishment of institutions relevant for social policies. For example, central offices of education and health were built on military predecessors (Suret-Canale Reference Suret-Canale1971: 310). In 1923, for example, the general Inspection of Sanitary and Medical Services and the Inspection of Education were established, and the education system was reorganized and decentralized (Buell Reference Buell1965). Over time, Africans educated as a result of the reform and expansion of social policy during this period were often involved in subsequent national political independence movements.

Indirect implications for social reforms

Besides the direct consequences of militarization, the end of WWI triggered processes that had indirect implications for the further development of social policies. Militarization, which was accelerated during WWI, created a new group which had not existed before, namely war veterans, or anciens combattants. Black soldiers who fought in overseas war theaters side by side with French citizens had been exposed to societies with political, civil, and social rights. This experience put the injustice of restrictions of these rights – through, for example, forced labor (corveé) – into stark relief and proved to be transformative.Footnote 3 After the war, it was almost impossible for theses soldiers to go back to a simple serving role (Summer and Johnson Reference Summers and Johnson1978: 27, 30). Even though war veterans were not able to act collectively after returning home from the demobilization camps, not least because they were distributed across a large area, they brought these experiences – what migration scholars refer to as “social remittances” (e.g., Levitt Reference Levitt1998) – back to their respective contexts. This often led to disruptions as war veterans demanded monetary compensation for their military service. Ex-servicemen also led dock, railway, and plantation workers to strike for higher wages. For example, in Guinea, annual political reports refer to the anciens combattants as “troublemakers” and “subversive” (Summers and Johnson Reference Summers and Johnson1978: 37). Specifically, French officials in Guinea reported in August 1918 that some African soldiers on leave “under the sway of ideas and tendencies which they had brought back from their contact with French workers” initiated major strikes in Conakry (ibid.: 30). Even though this did not lead to the creation of major veterans’, workers’, or soldiers’ lobby groups, it marked the point of departure for social unrest, demands for social rights, and the organization of social interests. This was reinforced by the fact that war veterans had acquired privileged freedom of expression that had been demanded by Diagne (Suret-Canale Reference Suret-Canale1971).

Moreover, recruitment efforts in tropical Africa revealed what was regarded as bad physical condition by the colonialists. This, as well as the absence of French language skills of indigenous populations, was not only problematic for imperial military endeavors but also very important for achieving the Empire’s economic objectives. Ultimately, this changed and strengthened narrative justifications for the expansion of social protection. This was exemplified in Sarraut’s famous developmental plan, La Mise en valeur (1923), which aimed to increase the productivity of the French Empire, including through the expansion of social protection:

“In fact, the first effect of education is to greatly improve the value of colonial production by multiplying the quality of intelligence among the mass of indigenous workers, as well as the number of skills; it… will compensate for the numerical insufficiency of Europeans and will satisfy the growing demands of the agricultural, industrial or commercial enterprises of colonisation” (Sarraut Reference Sarraut1923: 95; translated by the authors).Footnote 4

“The growth of colonial production is … above all, a question of manpower, of preserving the population and birth rate, conditioned by a major program of hygiene, medical assistance, and education” (Sarraut Reference Sarraut1923: 61; translated by the authors).Footnote 5

Basic health, sanitation, education, and language knowledge was then discursively linked to commercial value in mines, at trading stores, on plantations, and for building infrastructure (Hailey Reference Hailey1938: 1258), and French officials increasingly believed that education and health were necessary to make African men productive and for the colonial economic project to succeed (Conklin Reference Conklin1997: 137).

In sum, while education and health services for indigenous populations were not systematically expanded at a high level of quality after WWI, militarization started a process of extending medical and education services to indigenous populations, despite the insufficient and incomplete nature of their provision. Ultimately, militarization also increased the power resources of war veterans, some of whom later became engaged in labor and independence movements.

The warfare–welfare nexus in British colonies of West Africa

Direct implications for social reforms

In British colonies of West Africa, food shortages, famines, and epidemics triggered by the conflict continued long after its end, and ex-servicemen returned to a devastated and severely disrupted post-war economy that was ill-equipped to meet social needs, particularly in the area of health services. In many places, infrastructure was damaged or destroyed, and colonial administrations found themselves in debt after having borrowed money to support Britain’s wartime military objectives, which only disincentivized colonial governments from investing in social protection. In Nigeria alone, “the colony was compelled to undertake liability of up to £6,000,000 of the British Imperial war debt, with payment spread over thirty-six years including interest, which brought the amount to £13,250,000” (Njung Reference Njung2019: 54). This financial situation was further exacerbated by high inflation, which “significantly reduced the value of ex-servicemen’s pensions and gratuities Footnote 6 ” (ibid.: 54).

While the combination of the 1918 influenza epidemic and WWI illuminated the inadequacy of health service provision in British colonies of West Africa (and elsewhere), few changes were made, and we have uncovered no examples of movements to extend education services directly linked to the impact of WWI in British colonies of West Africa. One of the first outbreaks of the 1918 influenza pandemic spread from Sierra Leone through major transport routes and cities in the region. Freetown lost approximately 4% of its population in three weeks; in Nigeria, a total of approximately 460,000 people died from the epidemic; and the Gold Coast lost approximately 4% of its population in total (Tomkins Reference Tomkins1994: 68). However, neither the impact of the 1918 influenza pandemic on British colonies of West Africa nor WWI seemed to dramatically impact health service provision across the region. For example, after WWI, the whole of the Northern Province of Nigeria, with a population of over nine million, was served by fewer than 150 medical staff (Njung Reference Njung2019: 58). To address this shortage, the Nigerian colonial administration created the first school of medicine at Yaba in 1930 to train medical staff; however by 1937, the whole of Nigeria still registered only 220 medical staff for a population of over 20 million, and it was reported that the WAFF in Nigeria had no military medical units and fewer than 10 medical personnel before the onset of WWII in 1941 (ibid.: 58–9).

The disruption to social cohesion in British colonies of West Africa as a result of “voluntary” recruitment practices during WWI ran wide and deep. African servicemen who survived were housed in camps during de-mobilization, and these facilities were often overcrowded and faced food shortages. Furthermore, neither mobilization nor de-mobilization efforts were coordinated with sensitivity to the consequences of systematically removing able-bodied men from their communities:

“In many cases, the effect was to weaken the indigenous economy and traditional production, with few if any gains in the way of status and recognition from colonial administrations or working-class consciousness… Men, and women with children, might be suddenly drafted from agricultural production into military labour without any regard to the season of the year, whether a family starved, or the economic demands of a village community” (Killingray Reference Killingray1989: 487–8)

African troops who participated in the conflict were often seen as having betrayed their home communities by supporting the efforts of the colonizers, which further exacerbated difficulties they faced when trying to re-integrate (Fogarty and Killingray Reference Fogarty and Killingray2015; Njung Reference Njung2019).

Despite a decrease in labor supply resulting from the conflict and pandemic, the increase in numbers of socially dislocated men also increased the unemployment rate in modern terms and actually slightly lessened the cost of recruiting labor. This left African ex-servicemen in a more precarious position, rather than better placed, to demand social protection when compared to African servicemen of French West Africa. African ex-servicemen from British colonies of West Africa were also less financially resilient due to wage discrimination during the conflict itself. “Whereas a white British sergeant in the colonial army received a monthly salary of at least £6, his African counterpart of the same rank had to content himself with little more than £1” (Njung Reference Njung2019: 56). While in active service, British military officials often withheld gratuities, which amounted to the vast majority of wages, from African troops, making them payable only upon honorable discharge to prevent desertion, and some of these men were told that they would not return home but would instead be sent to the Middle East after WWI (ibid.: 56). African ex-servicemen also often received only gratuities and not pensions after the conflict, and furthermore, “soldiers deserving of gratuities were required to have had continuous good service for at least twelve years” (ibid.: 56). Moreover, for those who were discharged, claims for gratuities after the conflict, including by next of kin, were ended abruptly in September 1925, and it is estimated that the amount of gratuities that failed to be disbursed amounted to “about one-third of the total amount for which the men and their families were eligible” (ibid.: 56). While some British colonial governments in West Africa made an effort to place ex-servicemen into positions in the colonial civil service, the number of those who benefited was relatively small and the positive impact, while potentially of great importance to these individuals and their families, was limited (Fogarty and Killingray Reference Fogarty and Killingray2015: 105).

In sum, unlike colonies of French West Africa, British colonial governments of West Africa “simply failed to provide for those subjects who had fought to defend it” (Njung Reference Njung2019: 55).

Indirect implications for social reforms

In British colonies of West Africa, indigenous soldiers and servicemen did not benefit from social and economic reforms after WWI as many had in French West Africa, while British colonial governments paid down war debts and enterprises continued to seek profits. Despite a shortage of labor, the combination of the social exclusion of African servicemen from combat, their isolation during de-mobilization, and the absence of collective action in the form of veterans’ associations, resulted in few narrative, institutional, and political mechanisms through which indigenous soldiers and servicemen could advocate for recognition, service benefits, and paid work after the conflict. The few philanthropic organizations that did exist to support ex-servicemen struggled financially and had only meager resources available. In Nigeria, for example, this included a Disabled Soldiers’ Fund, the WAFF Reward Fund, and the Reward Fund of the Nigeria Regiment. In the end, only a small number of families and children received support after the death of a family member in service. Even though, “economic and monetary benefits, including the desire to achieve respectability and status, were crucial to the decision of African men to join colonial military service,” ex-servicemen were not a priority of the British Empire and its colonial administrations once the conflict ended (ibid.: 58).

Furthermore, social remittances from Europe in the form of civil, political, and social rights and notions of citizenship did not occur, as Britain utilized reinforcements from its dominions, but not from its colonies, in European theaters. Unlike in French West Africa, where the incorporation of indigenous populations into military service ultimately triggered an expansion of social protection and narratives that linked this to future economic development, the British continued to take a much more residual and exploitative approach to colonial development in West Africa that prioritized metropolitan profits, with little, if any focus on social investment in its colonies and their indigenous populations. Ultimately, British forms of political control and coercion in West African remained largely intact after WWI, even despite a reduced labor supply, and its colonial administrations made very few changes with respect to social protection despite increased demand for labor (Fogarty and Killingray Reference Fogarty and Killingray2015: 110).

The implications of warfare for welfare in West Africa: similarities and differences across empires

In many respects, the overarching objectives of both the British and French Empires in West Africa were the same: to ensure order within their respective colonies and to advance their commercial interests. However, this occurred within different imperial security and demographic contexts, resulting in different colonial strategies to achieve these ends. The British were able to rely largely on their naval power to secure their colonies and on the dominions for military reinforcements during WWI. In the absence of a comparable naval fleet and white population reserve, the French were more concerned about the depopulation of white French nationals. Therefore, the French welcomed the opportunity to raise a standing army in West Africa, while the British did not (Schmitt Reference Schmitt2020c).

Furthermore, the extent to which colonial societies were militarized differed to a large extent between French and British colonies of West Africa. The introduction of conscription in French West African colonies, the formalized nature of their recruitment practices, and French policy of assimilation led to a colonial society that was militarized in a more comprehensive way compared to British colonies of West Africa, where militarization was not a systematic characteristic of colonial governance. In British colonies in the region, military servicemen were recruited using the same set of informal, coercive practices and channels that were used to recruit indigenous laborers. Introducing conscription would have required the British to formalize this process, which was unlikely to have a positive impact on their ability to levy serviceman and risked damaging the Empire’s carefully crafted image as a philanthropic hegemon. Furthermore, in the British case, these servicemen were rarely trained for and did not directly engage in combat and were instead used as porters. The social exclusion of African servicemen from armed combat delegitimized their claims to the spoils of war (Echenberg Reference Echenberg1975, Reference Echenberg1991). In both cases, indigenous populations resisted forced recruitment practices, whether formal or informal, for example by migrating to British colonies after conscription was introduced in French West Africa and also through more explicit protests and uprisings (Killingray Reference Killingray1989; Koller Reference Koller2008).

In consequence, we observe different responses to the increased demand for social reforms in the aftermath of WWI in French and British colonies of West Africa, which affected both the form and nature of the warfare–welfare nexus. In French West African colonies, military conflict opened the door to a positively reinforcing cycle between military service and receipt of social protection and to expanding social protection to indigenous populations. To support continued mobilization of military forces, the French discussed greater social investments in both health and education in their West African colonies in a much more comprehensive way than the British did, going so far as to discursively connect this to their colonial development strategy. While post-war advances in social protection in French West Africa were still very limited in practice and were expanded less in areas with greater numbers of colonial subjects compared to citizens (Koehler-Derrick and Lee Reference Koehler-Derrick and Lee2023), advances were made nevertheless, for example through the formation of committees on education and health and the subsequent establishment of additional schools and hospitals. Also, after exposure to Western notions of citizenship and rights through combat in European theaters, French colonial war veterans who paid the “blood tax” demanded equal concessions for their sacrifice in terms of social protection and political rights, and these social remittances had some additional benefits for indigenous populations. In contrast, in British colonies of West Africa, early ideals of more equitably integrating indigenous populations into the WAFF failed to become a reality. The resulting lack of engagement of indigenous troops in armed combat only served to marginalize and disempower claims of social protection for those who had served and paid the “blood tax,” as well as for those who paid the ultimate price as porters. The marginal influence of warfare on social protection in British colonies in Africa, even despite post-conflict labor shortages, reflects the minimal extent to which the British relied on systematic militarization of colonial West African society to achieve its broader security and other imperial objectives.

When summarizing our findings on the warfare–welfare nexus in French and British colonies of West Africa, we observe that many relationships between warfare and welfare found in the Global North are also relevant in a colonial context. For example, in the case of French West Africa, we observe that concerns about public health and the skills of soldiers, as well as worries about the size of the population fit for military service were drivers of discussions on social reforms in the education and health sectors at the very least. Also, war veterans used the logic of equal sacrifice to claim social compensation. However, even though warfare fueled discussion of education and health services for indigenous populations, it did not automatically lead to a systematic and encompassing investment in education and health services. Expanding health and education services to the mass population would have required a large amount of resources and infrastructure that colonial powers did not have and in which they were not willing to invest. This was reinforced by the fact that metropolitan governments did not depend on votes from populations in the colonies. Therefore, the pressure to translate social needs generated by war into social policies was much lower. This indicates that some relationships, such as the need to increase mass loyalty or to react to the social needs caused by the war, may be of less relevance in a colonial context. Nevertheless, warfare triggered and accelerated the debate about social policies in a context that was hitherto characterized by an almost complete absence of social policies for indigenous populations. The comparison with British colonies of West Africa also shows that the relationship between military conflicts and social reforms is conditioned by the extent of militarization. In British colonies of West Africa, which were far less systematically militarized, warfare appears to have had much less influence on social policy debates compared to the highly militarized societies of French West Africa.

Conclusion

This paper examines the warfare–welfare nexus in British and French colonies of West Africa around WWI with a focus on identifying direct and indirect implications of military conflicts on social protection in a colonial context. It complements research focusing on the relationships between warfare and welfare in countries of the Global North (Obinger et al. Reference Obinger, Petersen and Starke, eds.2018). Consideration of the warfare–welfare nexus in a colonial context is necessary both in its own right and to ensure that theory building related to this nexus does not suffer from the Eurocentrism that is pervasive in the political economy and welfare state literature (Bhambra Reference Bhambra2021).

By analyzing primary and secondary data, this review finds that there are several mechanisms through which military conflicts affected social reforms in a colonial context. For example, the debate on social reforms in British and French West Africa was influenced by concerns about the skills and health of soldiers as well as the size of the population fit for military service. Thus, even though this did not lead to encompassing social services, warfare spearheaded a discussion on social services in colonial context, including for indigenous populations (Conklin Reference Conklin1997; Lasker Reference Lasker1977; Njung Reference Njung2019). The paper also finds that the degree to which warfare influences social reform is conditioned by the extent of militarization, which varied strongly across both Empires. While France introduced formalized recruitment practices in French West Africa, leading to a comparably highly militarized society, militarization in British colonies of West Africa was not a systematic characteristic of colonial governance. Consequently, the implications of warfare for welfare appear to be greater in French compared to British colonies of West Africa (Conklin Reference Conklin1997; Echenberg Reference Echenberg1991; Gamble Reference Gamble2017).

This paper focused on the direct implications of warfare on social policy discussions and reforms and also on its indirect implications for the power resources of war veterans. However, other indirect implications of WWI that could plausibly influence social reforms could not be analyzed in detail within the scope of this paper. For example, WWI strongly influenced the international institutional landscape, resulting in the establishment of international organizations, such as the International Labour Organization, which influenced social policies in dependent territories (Hepburn and Jackson Reference Hepburn and Jackson2021; Kunkel Reference Kunkel2018).

From a comparative perspective, future studies on WWI in the context of what became the mandated territories of Togoland and Cameroon may provide further insights into what most distinguishes British and French administrations and their approach to social protection in West Africa after WWI. These mandates might be particularly suitable cases to uncover causal linkages between warfare and welfare, as their creation and split offers the unique possibility of testing the effect of different imperial powers on social reforms. These and other studies examining the effects of these colonial legacies over time may help to historicize and close critical research gaps by widening and deepening our understanding of what have broadly been referred to as insecurity regimes in the global social policy literature (Wood and Gough, Reference Wood and Gough2006).