Satisfaction, Identity Salience, and Volunteer Role Identity

Psychology research concerning non-profit sector organizations frequently directs its attention to the psychology and permanence of their volunteers, as volunteers are indispensable members of NGOs and other unions to keep their prosocial actions alive. Volunteers invest considerable amounts of energy and time into these prosocial actions theoretically unrewarded. Literature has shown that volunteers have different reasons to engage in prosocial actions (e.g., Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder and Stukas1996; Chacón et al., Reference Chacón, Pérez, Flores and Vecina2010; Günter & Wehner, 2015; Planalp & Trost, Reference Planalp and Trost2009; Vecina Jiménez et al., Reference Vecina Jiménez, Chacón Fuertes and Sueiro Abad2010).

When people are performing a role like a volunteer for enough time, and under the right circumstances, they may internalize the role they perform as part of their self-identity (Penner, Reference Penner2002). Many of the studies in this field have focused on understanding the development and consequences of what is known as volunteer role identity (VRI) and have successfully found different factors that enhance it (e.g., Finkelstein, Reference Finkelstein2008; Grube & Piliavin, Reference Grube and Piliavin2000; Güntert & Wehner, Reference Güntert and Wehner2015; Marta et al., Reference Marta, Manzi, Pozzi and Vignoles2014; Moen et al., Reference Moen, Erickson and Dempster-McClain2000). One of the main functions of role identity is its ability to guide future behavior (Finkelstein, Reference Finkelstein2008). Thus, interest in VRI has been growing in recent decades to understand its origin, development, and its function on the permanence of volunteers in their organizations (e.g., Thoits, Reference Thoits2021; van Ingen & Wilson, Reference van Ingen and Wilson2017; Wakefield et al., 2021; Zlobina et al., Reference Zlobina, Dávila and Mitina2021).

According to the literature, volunteers who strongly identify with their role as volunteers should spend more time volunteering and should be the ones who remain in the volunteer task over time. For instance, Finkelstein (Reference Finkelstein2008) found that VRI correlated with time devoted to volunteering at 3 and 12 months, and Finkelstein et al. (Reference Finkelstein, Penner and Brannick2005) confirmed that VRI predicted time spent volunteering and length of service. These results suggested that the stronger the role identification is, the more likely the subject is to perform the behavior related to that role (Callero, Reference Callero1985). Another possibility might be that the more time an individual dedicates to a behavior, the more salient the role becomes (Thoits, Reference Thoits2012). Besides, Chacón et al., (Reference Chacón, Vecina and Dávila2007) showed in their prospective study that VRI was what better explained sustained volunteerism. However, VRI may need some indispensable conditions to arise, such as satisfaction with different aspects of volunteering.

Literature shows consistent evidence of the positive relationship between satisfaction and identity, and some authors consider satisfaction as one of the principal and necessary precursors of volunteer role identity and, in turn, permanence (e.g., Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Dunn, Bax and Chambers2016; Love, Reference Love2009). An explanation for that may be that satisfaction with the different dimensions of volunteering increment the centrality, probability of invoking the role, and, lastly, the importance of the volunteer role identity, leading to a higher identification along time. That is, satisfaction may augment and promote volunteer role identity through incrementing its saliency.

Identity Salience

Individuals hold multiple role identities simultaneously (See Stets & Burke, Reference Stets and Burke2000). While one individual may identify with the volunteer role, other sociocultural roles could be a source of self-identity too. These identities would guide our behavior, at least when they are active, using the sociocultural information that each role contains (Stryker & Burke, Reference Stryker and Burke2000). However, how multiple role identities organize and how this organization affects their ability to influence behavior remains unclear.

Theorists argued that the organization of multiple role identities could respond to their relative salience to the individual (Callero, Reference Callero1985; McCall & Simmons, Reference McCall and Simmons1978). Identity salience has received a great deal of attention in literature because the more salient a role is, the more motivated we should be to perform it (Thoits, Reference Thoits2013). Nevertheless, the conceptualization of salience has varied across the recent decades and research (Morris, Reference Morris2013; Thoits, Reference Thoits2013; see Table 1). One of the aims of this paper is to help clarify the concept overlapping that exists in terms of salience identity.

Table 1. Main Variables Associated with the Different Conceptualizations of Identity Salience

The different definitions of identity salience encompass both personal and social aspects. For example, Turner (Reference Turner1978, cited in Thoits, Reference Thoits2013) proposes that individuals identify with social roles that elevate their self-regard, consequently enhancing the salience of those roles. Turner also states that individuals identify with roles that hold significant interactions with others. These respects suggest that identity salience involves both personal and social dimensions, which, while inherently correlated, can be distinguished.

In our exploration of identity salience, we adopt a dual-concept approach. First, we utilize the concept of identity importance (Marcussen et al., Reference Marcussen, Ritter and Safron2004), which exclusively captures the subjective significance of a given identity role. Considering the diverse conceptualizations mentioned earlier, we further differentiate between personal and social importance. Second, we evaluate what may be more proximal to identity invocation – the location of a given role identity among others in terms of importance or centrality (as per Thoits, Reference Thoits1992, “salience hierarchy”). This aspect may be more associated with the individual’s propensity to evoke a particular role. To comprehensively address role identity salience, we advocate for the inclusion of both measures in our study. This approach aligns with the diverse perspectives on identity salience.

Satisfaction

Beyond its mixed conceptualizations, there is a compelling reason to posit that identity salience is closely related to satisfaction. As mentioned earlier, Turner asserted that individuals align themselves with social roles that elevate their self-regard and yield rewards. Consequently, we expect satisfaction to correspond to increased saliency of a role. Considering the multifaceted meanings of salience in the literature, it seems that satisfaction augments rewards, availability, and readiness to perform a given role. In other words, satisfaction reinforces the identity salience of a particular role.

Satisfaction is an essential variable in the study of sustained volunteering, not only due to its association with length of volunteering but also as a deemed prerequisite for volunteer role identity (Bang, Reference Bang2015; Benevene et al., Reference Benevene, Dal Corso, De Carlo, Falco, Carluccio and Vecina2018; Gonzalez, Reference Gonzalez2010; Greenslade & White, Reference Greenslade and White2005; Jamison, Reference Jamison2003; Shen, Reference Shen2013). We argue that satisfaction could serve as a precursor to Volunteer Role Identity by heightening the salience of the volunteer role. This would imply that the impact of satisfaction on volunteer role identity may be partially explained by the elevated identity salience resulting from sustained satisfaction.

In performing a volunteer role, satisfaction encompasses diverse rewards, such as enhancing self-regard, boosting self-esteem, and strengthening social connections (See Thoits, Reference Thoits2013). These rewards render the volunteer role more readily invoked, valuable, and ultimately more central to one’s self-concept. Consequently, we argue that satisfaction can concurrently enhance both the identity importance of volunteer role identity and identity invocation (the relative importance of Volunteer role identity compared to other roles). In summary, we propose that sustained satisfaction in the role of a volunteer intensifies the importance and invocation of volunteer role identity, ultimately fostering a greater identification with the volunteer role.

This Study

The objective of this study is to investigate the nuanced relationship between satisfaction, identity salience, and volunteer role identity (VRI). Specifically, we aim to explore how sustained satisfaction in the role of a volunteer contributes to the heightened salience of the volunteer identity. By investigating the dual dimensions of identity salience—namely, identity importance and identity invocation—we seek to understand how satisfaction influences the subjective significance of the volunteer role and its relative importance compared to other roles in an individual’s self-concept. Through this comprehensive analysis, we aim to provide insights into the mechanisms through which satisfaction may serve as a precursor to the development and reinforcement of volunteer role identity.

We expect that (a) satisfaction will predict VRI, (b) satisfaction will predict identity importance and identity invocation, and (c) that identity importance and identity invocation will partially mediate the relationship between satisfaction and VRI (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proposed Double Mediation Model.

Note. Salience identity would encompass both identity importance and identity invocation.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Two hundred and twenty-seven Spanish volunteers from NGOs from different areas (social assistance, ecology, sports, civil protection, etc.) completed the questionnaire. Women represented 64% of the sample, and the average age of the complete sample was 48.8 (SD = 15.9). Regarding employment, 55% of the sample were working or actively looking for a job at that time of the study. Regarding the marital status, 54% of the respondents were married or lived with their partner and 58% of the sample had one or more children. The average length of service of the sample was five years (SD = 7.9). The average time dedicated per week to volunteering was over five hours (SD = 6.99).

As a criterion for inclusion, the volunteer activity had to be continuous and not sporadic, with at least one voluntary action every fifteen days. To recruit the participants, we employed the snowball sampling technique. We contacted the organizations by email or telephone to gain access to their volunteers. Also, we posted an online advertisement on social networks to recruit participants. Participants answered a 15-minute questionnaire in digital format (remotely) and previously accepted informed consent about their participation. The deontology committee of the Complutense University of Madrid approved the relevant ethical aspects of the study. Participants did not receive any compensation for completing the questionnaire.

We performed an A priori power analysis in GPOWER (Erdfelder et al., Reference Erdfelder, Faul and Buchner1996) to determine if the sample was adequate in terms of power to calculate the analyses. We assumed a short-to-medium effect size, a power of.95, and two predictors (in the case of multiple regressions) and three predictors (in the case of the double mediation models). The power analysis determined a minimum of 81 to 90 sample size, which was accomplished in this study.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables. We assessed the sociodemographic variables such as age, sex, study level, work situation, marital status, and number of children.

Volunteer dedication. We assessed the previous time volunteering (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Penner and Brannick2005; Wakefield et al., Reference Wakefield, Bowe and Kellezi2022), the time devoted to volunteering last week (van Ingen & Wilson, Reference van Ingen and Wilson2017), and the weekly time devoted to other duties to address volunteering dedication.

Satisfaction. We employed the Volunteer Satisfaction Index (Vecina Jiménez et al., Reference Vecina Jiménez, Chacón Fuertes and Sueiro Abad2009), which assesses three subscales Likert-type from totally unsatisfied (1) to completely satisfied (7). Task satisfaction includes four items (e.g., “The tasks I usually do have clear and well-defined objectives”). Satisfaction with motives includes six items based on Clary et al. (Reference Clary, Snyder, Ridge, Copeland, Stukas, Haugen and Miene1998) (e.g., “The tasks I usually do as a volunteer let me establish social relationships with different people”). Lastly, satisfaction with the organization includes six items (e.g., “I am satisfied with the interest showed by the organization to take into account my preferences, abilities, and capacities to select the available volunteering positions”). In the present study, the coefficients of Mcdonald’s Omega for each scale were.84 (Task Satisfaction),.84 (Satisfaction with motives), and.94 (Satisfaction with the organization).

Volunteer Role identity. To assess the VRI we employed a set of items originally designed by Callero et al. (Reference Callero, Howard and Piliavin1987) and adapted to Spanish volunteers by Dávila de León et al. (Reference Dávila de León, Chacón Fuertes and Vecina Jiménez2005). The scale includes five Likert-type items from totally disagree (1) to totally agree (10) (e.g., “Volunteering is an important part of who I am”). The coefficient of McDonald’s Omega for this scale was.73.

Identity Salience. Given the diversity in concepts and definitions related to identity salience, it becomes apparent that a thorough investigation demands an exploration of two sub-concepts. By examining the identity importance, we can capture the nuanced significance of an individual’s connection to the volunteer role. Simultaneously, utilizing a ranking measure for identity invocation, as advised by Thoits, ensures a more unbiased and accurate assessment of the role’s relative importance in comparison to other concurrent roles. This dual approach allows for a more subtle and comprehensive understanding, acknowledging the multifaceted nature of identity salience in the context of volunteer role identity.

Firstly, we measured the social and personal importance of volunteering, employing a rating method as described by Marcussen et al. (Reference Marcussen, Ritter and Safron2004) and Martire et al. (Reference Martire, Stephens and Townsend2000). This understanding of identity salience involved participants providing a rating on a Likert-type scale, ranging from minimum importance (1) to maximum importance (7), for both the social and personal aspects of volunteering. Before rating, participants could read the following explanation: “Volunteering is an activity that involves benefits and affects our personal and social life. Next, please select the importance level that being a volunteer means to your social/personal life.” We term this measure as identity importance.

Secondly, we utilized a ranking measure involving participants placing a specific role, such as volunteering, among their currently active roles. Following Thoits’s (Reference Thoits2012) guidance and to minimize bias, we implemented a free-response ranking measure for what we term identity invocation. In this process, participants had to freely list five role identities and assess the importance of each. Subsequently, participants had to position the volunteer identity among these roles to establish a ranking measure. A higher score in identity invocation meant a higher position of volunteer role identity among the other roles.

Data Analysis

We employed SPSS (version 23.0) and JAMOVI (version 1.0.7.0) to conduct the analysis. Prior to analyzing, we examined the data for outliers, missing values, and assumptions of multivariate analyses. While no significant outliers were detected, we observed some non-pattern missing data classified into two types. First were random omissions to items without a pattern (less than 2% of respondents). Second were participants who did not finish the questionnaire completely (29% of respondents missed at least one response). To control these missing values and utilize real cases, we applied listwise deletion in all the analyses. We also performed a sensitivity analysis of double mediation models employing the missing data estimation approach FIML, acknowledged for proving unbiased estimates for random missing data (Enders & Bandalos, Reference Enders and Bandalos2001).

We describe quantitative variables using means and standard deviations. We employed linear correlations to assess bivariate relationships. We employed multiple linear regression to assess hypothesis (a) every dimension of satisfaction will independently predict volunteer role identity, and (b) every dimension of satisfaction will predict identity importance and identity invocation. Lastly, we performed two General Lineal Mediation Models to test hypothesis (c) identity importance and identity invocation will both simultaneously mediate the positive relationship between satisfaction and volunteer role identity.

Results

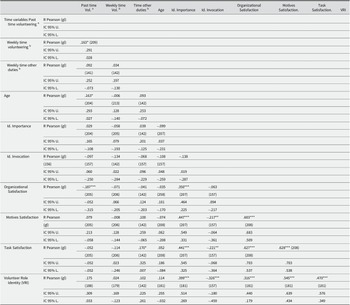

Firstly, we investigated any gender differences exploratorily, but analyses did not reveal any significant differences between men and women regarding any type of satisfaction, volunteer role identity, identity importance, and identity invocation. Those participants who were employed or actively looking for a job showed lower levels of satisfaction with the task, t(181) = 2.601, p =.01; and VRI, t(208) = 2.510, p =.013, than their counterparts. Having children and marital status did not reveal any significant association with the satisfaction-identity variables. Table 2 shows correlations for the key variables (Satisfaction types, personal importance, social importance, identity invocation, and VRI) and volunteer dedication indicators.

Table 2. Correlations between Age, Volunteer Dedication Variables, Satisfaction Dimensions, Identity Invocation, Identity Importance, and Volunteer Role Identity

Note. a Measured in days. b Measured in hours per week.

* p <.05.**p <.01. *** p <.001.

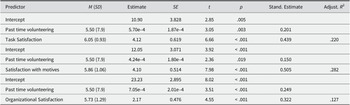

Regarding hypothesis (a) we tested if every type of satisfaction could predict VRI independently. We executed a linear regression model for each type of satisfaction introducing the past-time volunteering variable in the first step to control its effect, and the satisfaction dimension in the second step. As Table 3 shows, all types of satisfaction significantly predicted VRI.

Table 3. Descriptives of Satisfaction Dimensions and Lineal Regression Model for Each Type of Satisfaction predicting Volunteer Role Identity (VRI)

Note. N = 192; M (SD) = Mean (Standard deviation); SE = Standard error; Past time volunteering measured in years.

All regression models were significant p <.001.

Then, we executed linear regression models to test whether satisfaction could predict identity importance and identity invocation. Satisfaction with the task significantly predicted identity importance (p <.001, β =.441), and identity invocation (p =.005, β =.221). Satisfaction with the motives was also a significant predictor of identity importance (p <.001, β =.447), and identity invocation (p =.006, β =.217). Lastly, satisfaction with the organization predicted identity importance (p <.001, β =.350) but was unable to predict identity invocation.

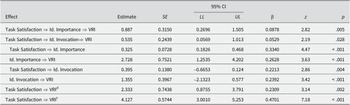

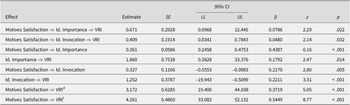

Lastly, we performed two multiple general lineal mediation models to test hypothesis (c), whether identity importance and identity invocation would mediate the relationship between satisfaction and VRI. We previously checked whether identity importance and identity invocation could simultaneously predict VRI. We found significant path estimates for identity importance (p <.001, β =.34) and identity invocation (p <.001, β =.280) with VRI. We did not execute a model with organizational satisfaction as a predictor because it was uncorrelated with identity invocation r(159) = –.063, p =.43. We end up with two possible models, one with task satisfaction and another with satisfaction with motives as predictors.

Figures 2 and 3 and Tables 4 and 5 showed that results for both models were significant. The first model proposed a double mediation of Identity Importance and Identity Invocation for the relationship between task satisfaction and VRI, which was significant. The second model remains identical, but the original predictor, which this time was satisfaction with motives. This second model was also significant. All direct and indirect paths of both models were significant.

Figure 2. Standard Estimates for the Double Mediation Model of Personal Identity Importance and Identity Invocation in the Relationship between Task Satisfaction and Volunteer Role Identity (VRI).

Note. *p <.05. **p <.01. *** p <.001.

Figure 3. Standard Estimates for the Double Mediation Model of Personal Identity Importance and Identity Invocation in the Relationship between Satisfaction with Motives and Volunteer Role Identity (VRI)

Note. *p <.05. **p <.01. *** p <.001.

Table 4. Double Mediation Model of Personal Identity Importance and Identity Invocation in the Relationship between Satisfaction with the Task and Volunteer Role Identity (VRI)

Note. d Direct effect. t Total effect.

Table 5. Double Mediation Model of Personal Identity Importance and Identity Invocation in the Relationship between Satisfaction with Motives and Volunteer Role Identity (VRI)

Note. d Direct effect. t Total effect.

Discussion

Our main hypothesis was that the path that leads from satisfaction to role identification should be at least partially explained by an increment in the identity saliency aspects, identity importance and identity invocation. As we expected, task satisfaction and satisfaction with motives to volunteer were related to the identity importance, the identity invocation, and VRI. Satisfaction with the organization showed a relationship with identity importance and VRI but did not show any association with the identity invocation.

Regarding the double mediation models analysis, the results emphasize the complex relationship between satisfaction, identity importance, identity invocation, and the development of volunteer role identity (VRI). The results show a notable direct and indirect predictive influence of satisfaction with the task and motives on volunteer role identity. This fact suggests that individuals who obtain satisfaction from the tasks performed and the underlying motives behind their volunteer activity may develop a stronger connection to the volunteer role.

This novel investigation of identity salience as a mediating mechanism sheds light on the underlying processes. The data suggests that satisfaction plays a dual role in influencing volunteer role identity through identity importance and identity invocation. Specifically, satisfaction strengthens the subjective importance of the volunteer role in an individual’s self-concept, as indicated by identity importance. At the same time, satisfaction reinforces the relative significance of volunteer role identity when compared to other identities, as indicated by identity invocation. This dual influence suggests that the impact of satisfaction on volunteer role identity is not only personal but also extends to the role’s status among an individual’s multiple roles.

The distinct measures employed for identity salience – one focusing on rating the importance of identity and the other on ranking measures for identity invocation – have proven valuable in providing a deep comprehension of the process addressed in this study. By examining both the individual’s subjective evaluation of the importance of volunteering and their placement of the volunteer role among other important roles, we capture the complexity of identity salience in influencing volunteer role identity.

One possible explanation for our results is that engaging in a specific role is associated with internal and external rewards, fostering an enhanced sense of self-reward (Turner, Reference Turner1978). This positive connection is established through the experience of satisfaction while performing the role. Furthermore, it would be possible that this positive association not only amplifies interpersonal connections related to the role but also makes the role more accessible and readily chosen, even in situations where individuals have the freedom to make their choices. In essence, the reinforcement of role driven by satisfaction would lead to an augmented significance of the role in the behavior, transforming it into an integral component of the self-concept. These findings align with prior research that underscores the interconnectedness of satisfaction, rewards, and the consolidation of role identity (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Penner and Brannick2005; Piliavin et al., Reference Piliavin, Grube and Callero2002).

Regarding satisfaction with the organization, we did not find a relationship to identity invocation, so we could not perform the proposed mediation model which included both identity importance and identity invocation. We think that organizational satisfaction may be perceived as more contextual-based than satisfaction with the task or motives. One may think that, for example, volunteering in another organization may definitively change their satisfaction with organizational aspects of volunteering as management style or leadership. However, it may not greatly vary the satisfaction with the volunteer task or motives to volunteer. In this sense, organizational satisfaction may be important to the personal and social importance of a given role when the role is assessed alone, but it may not be an essential variable when we mentally compare the role with other simultaneous role identities in a hierarchy.

Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of our study design restricts our ability to establish causality (Thoits, Reference Thoits2013). Although we can identify associations between variables, we cannot definitively infer the direction of influence. Future research employing longitudinal or experimental designs could provide more robust evidence regarding the causal relationships among satisfaction, identity salience, and VRI.

It is important to note that existing literature generally supports the notion that satisfaction precedes the development of role identity requiring time spent performing a role. While the design of this study does not allow for a conclusive determination of directionality, we align with the prevailing understanding in the literature that satisfaction likely plays a key role preceding the formation of volunteer role identity (e.g., Marta & Pozzi, Reference Marta and Pozzi2008; Thoits, Reference Thoits2013; van Ingen & Wilson, Reference van Ingen and Wilson2017). Yet future research with more temporally sensitive designs would offer a clearer perspective on the causal dynamics involved.

Another aspect that requires consideration is that we assessed personal and social importance using only one item each. While we believe this may not have substantially impacted the results, these items necessitate careful consideration. We considered that asking directly for the personal or social importance of the volunteer role identity would overlap with the VRI assessment. In fact, one of the VRI items probed whether being a volunteer was perceived as an important part of the self. We reasoned that inquiring about the personal and social importance of being a volunteer (along with its implications) would better capture the role importance rather than the identification. However, we acknowledge that the operationalization of identity salience remains an aspect that requires continued attention and refinement. Future research may benefit from a more nuanced and comprehensive approach to measuring identity salience to enhance the precision of these findings.

This study emphasizes the role of identity salience in bridging the relationship between satisfaction with volunteer actions and the development of volunteer role identity. The results suggest that identity importance and identity invocation independently contribute to this process of role identification. Our findings align with the notion that role identification takes time to develop. During this period, satisfaction may enhance the salience of the role, making it more prominent within the self-identity of the individual.

Authorship credit

Á. B. B. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing–original draft, and writing-review & editing. F. C. F. contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing–original draft, and writing-review & editing. I. d. l. O.-S. contributed to funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, and project administration.

Data sharing

The data are not publicly available due to ethical, legal, or other concerns.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades del Gobierno de España under Grant PID 2019-1073564RB-100.

Conflicts of interest

None.