In 1935, after decades of hard-fought battles, the American labor movement cemented the right to organize and bargain collectively with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), often called the “Wagner Act.” This legal victory provided the foundation for the continued growth of unions, and in the subsequent decade, waves of strikes and labor organizing spread throughout the country. The movement lost ground with the passage of the Taft–Hartley Act in 1947 but did not begin to decline in earnest until the 1960s. Curiously, however, the pronounced decline in private-sector union membership during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s coincided with the “phenomenal growth … of union activity in government.”Footnote 1 Today, 48.6 percent of all union members are employed by governments, and 32.5 percent of government employees are unionized, compared to only 6 percent in the private sector.Footnote 2

Many scholars have noted these divergent trends and pointed to the very different legal structures governing labor–management relations in the private and public sectors as an important contributor. The NLRA of 1935 explicitly excludes the public sector from coverage.Footnote 3 Government employees did not have legal protections similar to private-sector employees until decades later, and even then (for state and local workers) only at the state level, when during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, most states passed laws requiring government employers to recognize and collectively bargain with unions of their employees. Observing this, many scholars concluded that the development of public- and private-sector unions proceeded along separate paths throughout the twentieth century and that before the 1960s, organizations of government employees remained small, weak, and ineffective.

In this article, we show that this characterization of the pre-1960 public-sector labor movement is incomplete. Today, most government employees are employed by local governments (e.g., cities and school districts), and this was true at the turn of the twentieth century as well, when U.S. local governments raised more revenue and had higher expenditures than the federal and state governments combined.Footnote 4 The historical record indicates that local government workers formed organizations decades earlier than the 1960s, such as the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF), established in 1918, and the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), established in 1915. Yet until now, there have not been quantitative analyses of the presence of public-sector organizations in local governments before the critical decade of the 1960s. We introduce a new dataset that allows us to see when and where these organizations spread across the United States. We show that by 1940, hundreds of cities had organized workers. Moreover, by 1950, dozens had public-sector unions that had engaged in strikes; even more had unions that had secured written agreements with their city employers; and qualitative evidence shows that local government employee organizations were active in local politics. In addition, by 1960, our data indicate that at least 541 cities already had organizations of police officers. Thus, long before Wisconsin passed the first “duty-to-bargain” law in 1959, in many cities, local government workers were organized and showed signs of influence.

We also present evidence that public- and private-sector employee organization were correlated during this period. Our analysis shows that the presence of a private-sector Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) local in a city in 1940 is associated with the city also having a city employee organization at that time. We also find several examples of private-sector unions (both CIO and those affiliated with the American Federation of Labor [AFL]) helping city employees to organize or trying to organize city employees themselves. Thus, even though the legal institutions governing private- and public-sector unions were clearly distinct, our evidence suggests that the timing and location of public-sector organization during this period may have had more in common with private-sector organization than is often recognized.

Separate paths? Literature, theory, and contemporary context

Accounts of government employee organizations usually start in the 1960s, and research on earlier decades presents a very mixed picture of the extent of their organization and activity. Much of the scholarship in political science, economics, and public administration highlights the different developmental path of public-sector unions from private-sector unions and the weakness of government employee organizations during the first half of the twentieth century. A major focus in this literature is the exclusion of government workers from the NLRA. Walker explains that little is known about why the U.S. Congress excluded government workers from the landmark labor legislation but speculates that few recognized at the time how consequential the omission would turn out to be for the labor movement.Footnote 5 State and local government employees never achieved a federal “Wagner Act for Public Employees.”Footnote 6 Instead, public-sector labor–management relations laws for state and local employees were passed by the states, in piecemeal fashion, and much later. The first law requiring collective bargaining was passed in Wisconsin in 1959, and the next state “duty-to-bargain” laws did not come until 1965—a full three decades after the NLRA.Footnote 7

Experts generally also agree that there was greater antipathy toward public-sector unions than private-sector unions during the first half of the twentieth century. While government employees organized vigorously during the 1910s, especially firefighters and police (many of whom sought and obtained charters from AFL), the Boston police strike of 1919 turned many political elites against government employee unions. President Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote in 1937 that “collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service.”Footnote 8 A large part of this resistance stemmed from fear of public-sector strikes.Footnote 9 Many worried that unionization would divide the loyalties of government employees like police officers and postal workers: that is, instead of being solely committed to the state and the neutral fulfillment of their duties, unionized public employees would also have loyalty to the union,Footnote 10 which “might introduce dangerous elements of class bias and partisanship” to their work.Footnote 11 Another prominent argument held that the notion of collective bargaining in government clashed with the doctrine of government sovereignty and would represent an improper delegation of governmental power.Footnote 12 Until the 1950s, moreover, many viewed civil service as the proper governance system for personnel matters in the public sector, and thought that the labor–management relations practices used in private industry were inappropriate or unnecessary.Footnote 13

In addition, most experts agree the laws governing labor–management relations mattered immensely for the extent and timing of unionization. The NLRA was a pivotal moment for the private sector.Footnote 14 For the public sector, experts point to much later critical events that sparked unionization, including New York City’s municipal order granting city employees formal collective bargaining in 1958, Wisconsin’s pioneering duty-to-bargain law in 1959, President John F. Kennedy’s 1962 Executive Order 10988 providing limited collective bargaining rights for federal employees, and the wave of state laws passed between the late 1960s and early 1980s.Footnote 15 Numerous scholars argue these state laws were critical to the widespread unionization of the public sector.Footnote 16 As labor economist Richard Freeman puts it, “What changes led to the sudden organization of traditionally nonunionizable public sector workers? First and foremost were changes in the laws regulating public sector unions.”Footnote 17

Political science scholarship theorizes that favorable laws helped teachers’ unions overcome the daunting collective action problems they faced.Footnote 18 And because the public-sector laws came much later than those of the private sector, Walker writes that “government union growth was artificially repressed, and its delayed growth during the peak of private sector union ascendance was a key missed opportunity.”Footnote 19 She concludes that the “seemingly minor exclusion in the Wagner Act has set public and private sector unions on separate development paths that continue to resonate today.”Footnote 20

Throughout this literature, however, scholars also acknowledge that many governments had public employee organizations before there were any supportive laws.Footnote 21 At the federal level, Goldfield describes how employee organization predated Kennedy’s 1962 executive order, especially among postal workers, who were “already over 70 percent organized in 1939.”Footnote 22 Case studies of how the state laws were passed in Wisconsin and Michigan highlight the importance of advocacy by public-sector unions such as IAFF and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME).Footnote 23 While some have treated the state laws as exogenous to outcomes of interest,Footnote 24 others have argued that the laws were most likely both a cause and an effect of public-sector unionization—and thus that public-sector unions had to have sufficient organization and strength in order for the laws to be passed in the first place.Footnote 25

This raises questions about what, exactly, the state of local public employee organization was before the 1960s, but these questions have barely been explored. There exist qualitative accounts of particular organizations and particular cities like Philadelphia,Footnote 26 which indicate that many public-sector workers managed to organize even without supportive institutions, but no scholarship documents where and when government employees organized during the first half of the twentieth century. Moreover, the quantitative data that have been used in existing work to show low rates of public-sector organization prior to the 1960s almost certainly understate the extent of government employee organization at the time.

One reason for the conclusion that public-sector organizing was weak before the 1960s is that the term “union” was (and is) controversial and hard to define for all involved, including public employees, public officials, and scholars writing about this historical period.Footnote 27 In the private sector, there was little ambiguity: in an industrial plant or other private-sector entity, once employees elected to unionize, they were clearly a union, the machinery of the NLRA applied, employers were required to collectively bargain, and employees could strike in the case of an impasse. For government workers, there was no such clarity. Some groups of public employees were (and still are) labeled “associations.” Others were considered fraternal organizations. Many insisted that they were not unions,Footnote 28 which is perhaps unsurprising given that some cities expressly prohibited public employees from joining unions,Footnote 29 and in others, powerful patronage-based machines blocked the effectiveness of autonomous employee organizations.Footnote 30

Organizations also varied in whether and how they involved managers and administrators, whether they adopted union tactics like strikes, and whether and when they pursued union goals like dues checkoff, formal grievance procedures, and collective bargaining.Footnote 31 Experts on teachers’ unions have shown that before the 1960s, the National Education Association (NEA) was a professional association run by administrators that did not seek collective bargaining or condone strikes. However, many locals of other public-sector employee organizations—including many of those we analyze below—had charters from the major labor federations. IAFF and AFSCME, for example, had charters from AFL, and the State, County, and Municipal Workers of America (SCMWA) affiliated with CIO. Thus, some local employee organizations expressly affiliated with the labor movement, while others did not. Oftentimes these factors varied across locals within the same national organization, and for many organizations, they varied over time. Levi, for example, describes how police organizations in three cities gradually transformed into de facto unions.Footnote 32 Even today, there isn’t an agreed upon definition of what, exactly, makes an organization of public-sector employees a “union” versus an “association,” nor at what moment preexisting organizations became unions.Footnote 33

Presumably, much of this ambiguity was resolved around the time that states started passing duty-to-bargain laws for public-sector workers. With momentum building and eventually a legal apparatus established, it would be reasonable to think that many preexisting employee organizations began to refer to themselves—or to be referred to—as unions. The literature on teachers’ unions shows that this was the period in which competition from the rival American Federation of Teachers (AFT) spurred the transformation of NEA from a professional association run by administrators to a teachers’ union that embraced collective bargaining.Footnote 34 Therefore, while the state laws spurred new organizations in some cities and school districts, they also almost certainly led many existing organizations to explicitly consider themselves (or to be considered) unions.

This ambiguity is embedded in the data on public-sector union membership during this period (which are scarce to begin with). One source, used by Freeman, is the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) biennial statistics, which only started including “associations” in its count of public-sector employee organizations in 1968.Footnote 35 Prior to that, its figures only included those it deemed to be “unions.” The BLS data therefore make it look as though public employee organization was quite low as of the early 1960s and then much higher starting in 1968. But this rise is largely due to an expansion in the types of organizations included in the count.

The other source of early public-sector union membership data used in existing scholarship is the Union Sourcebook compiled by Troy and Sheflin.Footnote 36 As Walker’s plot of these data shows, it looks as though public-sector union density was very low until 1960—10.8 percent of public employees—and then suddenly jumped to 24.3 percent by 1962.Footnote 37 The problem, which Troy and Sheflin acknowledge, is the same one that plagues inferences from the BLS data: in many cities and school districts, local employees were organized in “associations”—and were not counted as “unions” in years up to 1960.Footnote 38 This is made clear when Troy and Sheflin changed their strategy in 1962 to include associations, and the total number of organized employees jumped 140 percent in 2 years. 1962 was also the year of Kennedy’s executive order, but notably, the increase reported in the Union Sourcebook was mostly for local and state government: while federal union membership increased from 541,000 in 1960 to 628,000 in 1962, local and state membership increased from 307,000 to 1,592,000.Footnote 39 As Troy and Sheflin explain, “It is in 1962 … that we began to include many associations in our universe.… Thus, some of the large jump in public sector membership seen in 1962 represents expanded coverage. For example, the National Education Association enters our universe in this year.”Footnote 40 Thus, the BLS and the Union Sourcebook public-sector union data undoubtedly understate the extent of local public employee organization before the 1960s. Conclusions about the divergent paths of public and private unionization rely heavily on these data, and so also understate the extent of public employee organization in the pre-1960 period.Footnote 41

Another feature of this literature is that it tends to focus on laws passed and positions taken by political elites, with particular emphasis on what was happening at the federal and state levels. Walker, for example, stresses the importance of the absence of a federal law for government workers.Footnote 42 In their edited volume on public-sector unions, Valletta and Freeman introduce a new dataset of state labor–management relations laws from 1955 to 1985,Footnote 43 and numerous studies estimate their effects.Footnote 44 In addition, qualitative examples of antipathy to public-sector unions often feature quotations from elites like big-city mayors, U.S. presidents, governors, and judges. For example, in justifying firing four firefighters for joining IAFF, Cincinnati’s Mayor Galvin explained, “a union is subversive of the discipline of the department.”Footnote 45 When asked his feelings on Philadelphia police officers joining FOP, the director of public safety asserted, “I am absolutely opposed to it … I readily see where it might be productive of great harm.”Footnote 46 The mayor and aldermen of Winston-Salem declared, “It is to the best interests of the City of Winston-Salem that no labor organization ever be recognized as a bargaining agency or representative of any employees of the city of Winston-Salem.”Footnote 47 Clearly, many elites were quite opposed to public-sector organizing.

As a result, public employees were stymied in their efforts to achieve protections at the national and state levels because those in power were hostile to their goals. For a long time, they were rebuffed in state legislatures due to legislative malapportionment, rural dominance, and powerful patronage-based regimes.Footnote 48 Yet the emphasis on state and federal laws and political elites may also have led scholars to underestimate the spread and strength of public-sector employee organization prior to 1960, and to overstate the extent to which the growth of public- and private-sector unions followed separate trajectories in the early twentieth century.

If we instead put emphasis on what was happening in local governments and consider matters from the perspective of workers and their organizations, as some labor historians have done,Footnote 49 our expectations might be different. We might even find reasons to expect that the development of the public- and private-sector labor movements had a great deal in common—and that the advances of government employee unions may have more closely tracked the strength of private-sector unions than is usually acknowledged.

For starters, the work, grievances, and goals of many government employees were very similar to those of workers employed in the private sector. While it is often assumed that the government workforce was predominantly white collar, it was not,Footnote 50 especially in municipal governments, where the employee mix included transit workers, trash collectors, police officers, firefighters, and public works employees. Not only were some of these employees bound to their private-sector counterparts by similar kinds of work, but they also shared similar grievances, including low pay, poor working conditions, little safety net, and in some places lack of security due to patronage. As Mire reported, “The economic plight of public employees is serious.… A great number of public employees receive remuneration far below the most modest concept of a living wage.”Footnote 51 It therefore seems reasonable that ideas that inspired trade unionism in the private-sector—such as worker solidarity and industrial democracy—would have also inspired and animated some public-sector employees.Footnote 52

There is also good reason to expect there were strong social ties between public- and private-sector employees living in the same areas, and that these ideas about unionism would have been shared within these networks, regardless of whether particular individuals worked for a city, in a mine, or in an industrial plant. As Newman and Skocpol describe, for many decades, unions were the backbone of community networks and hubs of social life and culture.Footnote 53 They write, “Unions … wove themselves—their people, their local leaders, their facilities, their names—into the very underpinnings of community and social life.”Footnote 54 While Newman and Skocpol focus on private-sector unions, there is little reason to think that this reach of union culture would have stopped at the boundary of government employment.

Organizational incentives in the public and private sector were likely also similar. Organizations have a basic, fundamental need to persist, grow, and fend off competition.Footnote 55 For unions, that means maintaining membership and finding new members to organize (before rival unions do). Holmes argues that private-sector unions during this period may have had spillover effects: that once unions were established and had high membership in certain areas, there may have been a tendency for those unions to seek to organize other workers in the same area, and thus for unionization to spread in geographically proximate places.Footnote 56 While there was almost certainly variation across place, economic sector, and union affiliation in both interest in and intensity of organizational expansion, some private-sector unions may have looked to government employees as possible new members to organize, even before the 1960s. And once organized for some workers, public-sector unions may have encouraged the spread of unionization to other positions.Footnote 57

Political scientists have also highlighted the collective action problems government employees faced and how the passage of state labor–management relations laws helped solve them by generating new, powerful incentives for public employees to form and contribute to unions.Footnote 58 More generally, scholars have noted that many organizations form and grow because they are subsidized by government policies, foundations, and political entrepreneurs.Footnote 59 We propose that in the case of public-sector unions, encouragement and support from other unions may also have helped—before the laws were passed.Footnote 60 This is therefore a different way in which government employees may have solved the collective action problem and by which public-sector unions spread: with the encouragement, energy, camaraderie, and help of other unions, including private-sector unions.

Importantly, some scholars have noted that in states, public-sector union density is correlated with private-sector union density;Footnote 61 we propose that some of this correlation could reflect the direct ways private- and public-sector unions worked together and collaborated during this period. At a basic level, many unions had (and still have) both public- and private-sector members.Footnote 62 Today, for example, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) have both public- and private-sector members. The same is true for many occupations. For example, some transit engineers work for private rail companies, and some work for local governments; similarly, both public and private entities employ plumbers and electricians. Early in the twentieth century, some private-sector unions may have tried to organize city employees, and others may have aided city employees in their organization and activities, such as by joining strikes or helping their electoral efforts.

None of this is to say that the state laws were unimportant, because of course, they spurred union growth and spread formal collective bargaining.Footnote 63 The effects of the laws may have been especially important for union organizing in small and mid-sized cities and for the rise of teachers’ unions.Footnote 64 More generally, the state laws created a reliable legal structure for organizing, guaranteed collective bargaining, and offered stability and predictability from administration to administration. Our point is simply that well before the laws, government employees may have overcome their collective action problem with help from the private sector.

Because their employers were local government officials, moreover, public-sector unions also had the option of pursuing their goals through politics—even in the absence of legislation requiring employers to bargain with them. In local government, the managers were (and are) chosen in local elections.Footnote 65 Public-sector employees could therefore try to use the power of their votes and their political influence to convince elected officials to comply with their demands. This likely served as an additional incentive for public-sector employees to organize, because if they could band together and exert political pressure, the result could be a local administration more inclined to increase pay and improve working conditions.

Lastly, while existing research emphasizes how state laws influenced what happened at the local level, we propose it is equally important to acknowledge how earlier local-level dynamics influenced later events at the state level. As we mentioned above, case studies suggest public-sector unions were involved in the eventual passage of state collective bargaining laws.Footnote 66 Moreover, state-level advocacy by public-sector unions did not start in the 1950s and 1960s; for at least two decades, local public-sector unions had regularly lobbied state legislatures for favorable policies on civil service, work hours, and the terms of employment.Footnote 67 As the Silver Bow, Montana, IAFF explained in 1936,

Our constitution in the I.A.F.F. forbids us to use the ordinary weapon of labor, to strike, inasmuch as a strike of our department would jeopardize the lives and property of every person in the community and would lay all classes open to great danger, so the only hope of security we have is in securing state laws to protect us.Footnote 68

Thus, we propose that in many cases, political dynamics that began in local governments through the efforts of local organizations expanded, grew, and influenced state politics.

All of this points to a pressing need for a better understanding of the rise, spread, and power of early local public employee organizations. As many scholars have noted, the developments of the U.S. labor movement between the 1930s and the 1980s profoundly affected American politics and the contours of the U.S. economy.Footnote 69 And yet, the origins and early development of half of today's existing labor movement—that of the public sector—remains poorly understood. In the following sections, we explore the evolution of city employee organizations with new data. What they suggest is that even though public- and private-sector unions developed along separate legal paths, organizations of government employees formed in many cities even without a favorable legal structure—around the same time and in many of the same places as private-sector unions.

Data on early public employee organizations

To study public-sector organizations, we built a dataset from tables of the Municipal Yearbooks, collected by the International City/County Management Association (ICMA). The annual Yearbooks contain a wide range of statistics describing the governance of incorporated municipalities (e.g., cities, towns, and villages) in the United States starting in 1934. For this article, we have digitized and assembled data tables of the Yearbooks from 1938 to 1962 that include information on the existence of city employee organizations and, for certain years, some historical detail about them.Footnote 70 Our data are arranged by city-year, and for the most part, they are reliable indicators of employee organizations that existed from 1902 to 1956 for cities with more than 10,000 people.

There are many challenges with the data, which we describe in detail in the online appendix. Cities enter and drop out of the dataset for various reasons (e.g., they were too small, or no data could be obtained in certain years). Additionally, the ICMA changed the way that the data were gathered and presented in certain years.Footnote 71 Finally, we know that sometimes union/association locals disbanded, so we cannot assume that once an organization was established it persisted in future years. To deal with these challenges, we take two different approaches for our analysis. First, we identify 917 cities for which we can consistently track the presence and absence of city employee organizations at six points in time: 1920, 1935, 1940–1941, 1944–1945, 1949–1950, and 1955–1956. We use this set of cities to evaluate change over time in the spread of employee organizations. Second, for other analyses, we use all available data (allowing cities to enter or drop out of the dataset) to show snapshots of organizational strength at particular moments in time.

The ICMA gathered data consistently for two organizations, both of which were affiliated with AFL and still exist today: IAFF and AFSCME. In addition, the Yearbooks consistently collected data on city employee CIO locals, although the particular organization changed over time. Starting in the late 1930s, when CIO split from AFL, the Yearbooks track SCMWA. Then, in 1946, SCMWA merged with United Federal Workers of America to form United Public Workers of America (UPWA), and starting in 1951, the Yearbooks also tracked local organizations of CIO’s Government and Civic Employee Organizing Committee (GCEOC).Footnote 72 Finally, the Yearbooks collected consistent information on unaffiliated organizations starting in 1944.

The data on police organizations are much more complicated because (as we describe in the next section) the organizing of police was much more complicated. The largest and most widespread police organization was and is FOP. However, the Yearbooks only include FOP data in particular years. Additionally, in some cities, police were organized by AFSCME. For some years, where the AFSCME local only included police officers, we know the location of these organizations. Finally, the Yearbooks present information for 1959–1961 on whether police in the city were unionized. To get a sense of how widespread police organizations were prior to the 1960s, we combine all of these pieces of information to denote cities with an active or formerly active police organization as of 1960.

Our data cannot tell us whether any organization thought of itself as a union or an association, nor whether others considered it to be a union, and we have no comprehensive information about their participation in electoral politics or public policy. Up to this point, however, quantitative data on the existence of early local government employee organizations did not exist. With additional information from some of the Yearbooks, we know the location of municipal worker strikes (for 1947–1951) and where organizations had achieved written agreements with city employers (for 1945–1950), and we present these data below.

Before the laws: city employee organizations 1902–1956

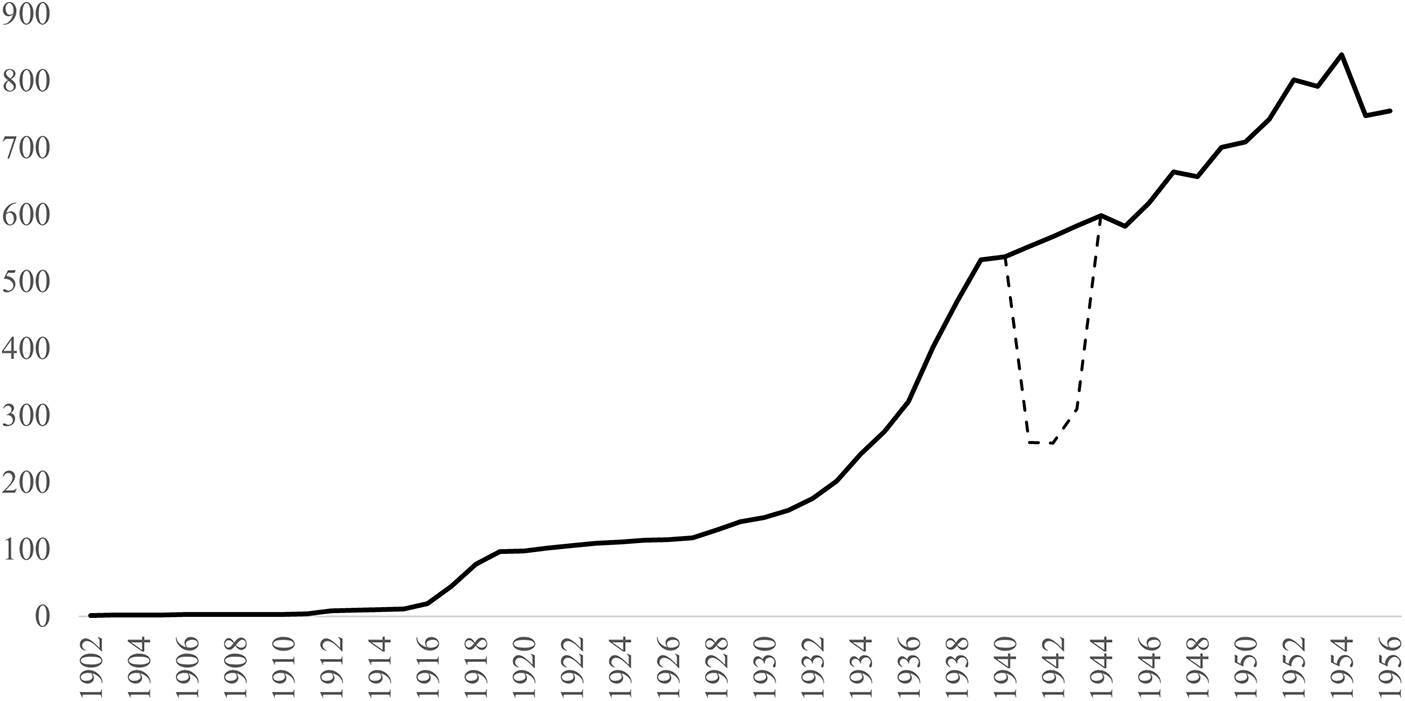

We begin by showing data over time on the total number of cities with any municipal employee organization. In Figure 1, we use all of the cities in the ICMA Yearbooks and plot the total number of cities with a known employee organization from 1902 (the year the unaffiliated San Francisco Municipal Civil Service Association was established) to 1956. As we have said, the total number of cities reported on in the Yearbooks fluctuates between 1940 and 1956. The total is especially low in 1941–1943 due to a higher population threshold for inclusion, and so the solid line in the figure interpolates between 1940 and 1944. Figure 1 suggests that the early twentieth century was a time of incredible growth for public employee organizations.

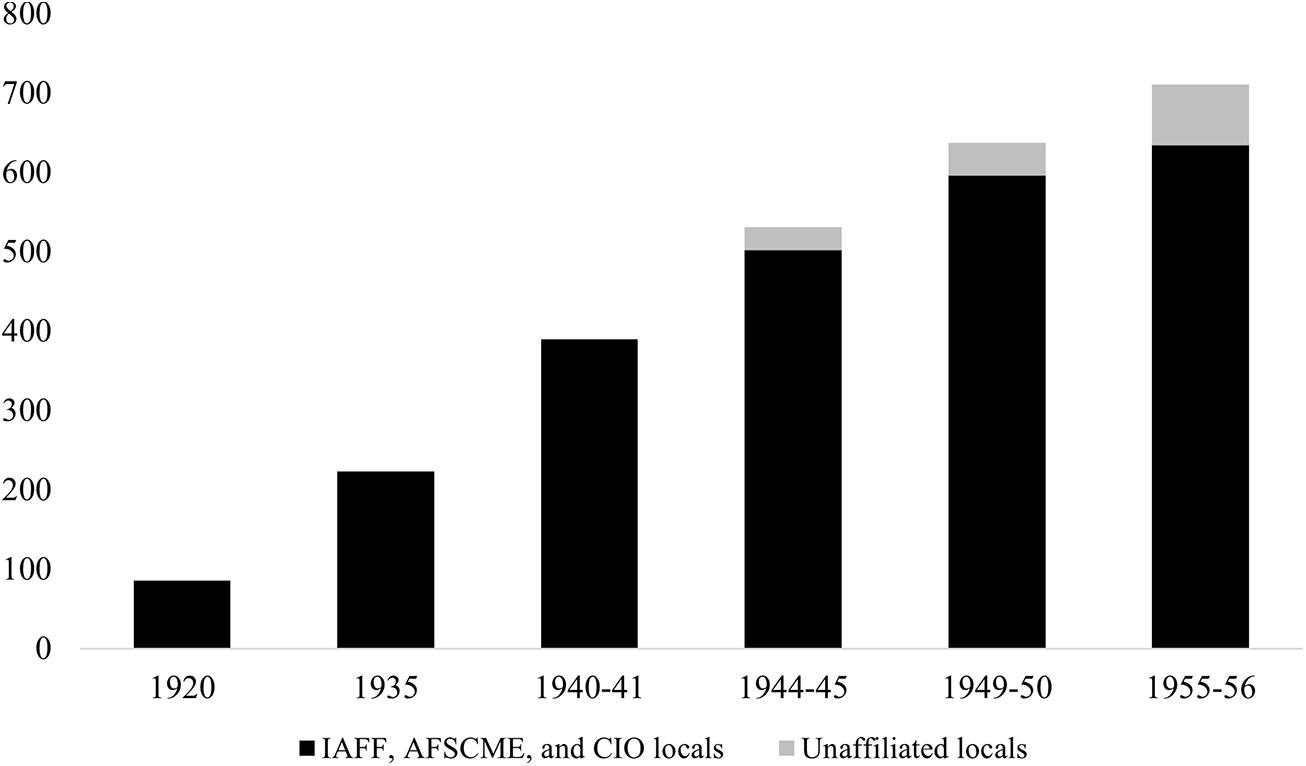

Figure 2 limits the data to the 917 cities where we can consistently track employee organizations over six points in time, and the same picture emerges: By 1920, there were already eighty-six cities in this set with employee locals thanks to the early organization of IAFF. Then, after slow growth during the 1920s (see Figure 1), the 1930s and 1940s witnessed explosive organizing activity by city employee unions as AFSCME burst onto the scene in 1935 and SCMWA split off a few years later. As of 1935, 223 of these 917 cities had organizations, nearly all of which still were IAFF. Writing in 1937, the director of the National Association of Civil Service Employees asserted, “the policemen and firemen are, like the teachers, well organized. Practically every city has its associations covering the uniformed forces, even though the strength of the units may vary widely.”Footnote 73 By 1940–1941, the total number of cities with IAFF, AFSCME, or CIO locals in this set had risen to 390, and then the number continued upward to 634 in 1955–1956. In addition, the Yearbook data allow us to track unaffiliated locals for these 917 cities between 1944–1945 and 1955–1956. There were a number of additional cities during this period that had organizations that were unaffiliated with IAFF, AFSCME, or CIO (gray bars). What these preliminary figures reveal is that by 1956, most cities with more than 10,000 residents had city employee organizations, and that there was significant spread of city employee organizations in the years immediately following the NLRA and during the peak of private-sector union strength.

Figure 1. Total Number of Cities with a Known Employee Organization.

Figure 2. Number of Cities with Employee Organizations (Set of 917).

In addition to shedding new light on the timing of the spread of public-sector organizations, our data allow us to explore the geography of that spread. We start with IAFF, using the set of 917 cities to document the location and spread of IAFF locals. As we describe elsewhere,Footnote 74 IAFF was a pioneer of city worker organizing: it organized firefighters in hundreds of cities during the late 1910s and the 1930s, with the first IAFF locals cropping up in cities that were close to centers of mining and/or steel production. By 1920, IAFF locals were already established in eighty-six cities within this set of 917. As of 1935, the year AFSCME was created, IAFF had locals in 223 of the 917 cities, not only concentrated in heavily industrial states like Ohio and Indiana but also present in states like Wyoming, Alabama, and West Virginia. Figure 3 shows the geographic spread of IAFF locals as of 1940–1941; by that time, 39 percent of the cities had organized firefighters. The growth of IAFF continued after World War II (WWII). By 1955–1956, 60 percent of these 917 cities with more than 10,000 residents had an IAFF local.

Figure 3. IAFF Locals, 1940–1941.

AFSCME got a later start but also expanded rapidly in the years following the NLRA. In 1935, the nascent AFSCME had locals in only three cities in our set of 917: Milwaukee, Seattle, and El Paso. By 1940–1941, AFSCME had organized city employees in 139 of these cities, shown in Figure 4 (as well as fifty county governments, not shown here). As with IAFF, AFSCME was concentrated in the Midwest but not confined to it: it had locals in cities ranging from Pueblo, Colorado, to Mobile, Alabama, to Yakima, Washington. By 1944–1945, it expanded further in these areas as well as to more eastern cities and cities in Southern California. By 1955–1956, 41 percent of the cities in this set of 917 had an AFSCME local.

Figure 4. AFSCME Locals, 1940–1941.

Public-sector CIO locals and unaffiliated locals also spread across the United States during the 1940s and 1950s (see the online appendix). SCMWA locals were most numerous in the industrial Midwest, but by the 1950s, many CIO organizations also represented city workers in other parts of the country, with locals in 114 of the 917 cities in 1949–1950. While we cannot track unaffiliated locals consistently for years before 1944–1945, our data show they were already numerous by the end of WWII. As of 1949–1950, 186 of the 917 cities had unaffiliated locals. By 1955–1956, the number of cities with unaffiliated locals had increased to 332.

Moreover, the data suggest that once a city government had one organization, other public-sector organizations gravitated toward organizing city employees in the same place. Examining all the city data we have for 1937, for example, we find that of the ninety-six cities that had an AFSCME local that year, seventy-three also had an IAFF local. Moreover, sixty-eight of those IAFF locals were established earlier than the city’s AFSCME local. (In the remaining five, they were established the same year.) Similarly, twenty-eight cities had SCMWA locals in 1937, and twenty of those also had an IAFF local (seventeen of which predated the SCMWA local). Thus, the expansion of AFSCME and SCMWA between 1935 and 1940 mostly happened in cities that had organized firefighters.

Figure 5 presents a more comprehensive snapshot, showing all cities where there was any known city employee organization as of 1955 or 1956 (using all the data we have), including IAFF, AFSCME, CIO locals, and unaffiliated locals. Of the 1,173 unique cities covered in the Yearbooks in 1955 and 1956, 829 of them had locals of at least one of these organizations. While many were in the Midwest and Northeast, there were city employee organizations in all forty-eight states, including not only states like California and Washington but also states of the South and Mountain West. And many of these cities had multiple organizations. By 1956, for example, 76 percent of the cities that had AFSCME locals had IAFF organizations as well.

Figure 5. All Known Employee Organizations, 1955–1956.

The glaring omission in these figures so far is police organizations. While historical evidence indicates that police officers in many cities were organized quite early, accounts also suggest that resistance to police organizing might have been uniquely strong during this period. At different times and in different places, opposition came from negative responses to the Boston police strike, concerns about dual loyalties of police officers, and resistance from big-city machines (for which controlling the police may have been especially important).Footnote 75 Although some labor leaders resisted police organization because they were concerned about the role of police in breaking up strikes, for the most part, the opposition to police organizing came from municipal elites and business owners, not from private-sector unions. Numerous city governments formally prohibited the police from unionizing,Footnote 76 and corporations like Anaconda Copper and Lackawanna Steel often requested that officers put down strikes.Footnote 77 One possibility, then, is that police officers really were not well organized until the state laws were passed.

The Yearbook data have incomprehensive coverage of police organizations, but as a way of gaining some insight into the extent of police organization prior to the 1960s, Figure 6 maps all cities that had a known police organization in 1960 or in an earlier year. This includes (1) cities where the ICMA data report that the city had “unionized police” in 1959 or 1960, (2) cities where the 1943–1956 data indicate that an FOP local existed in at least one of the years, and (3) cities where we know that in some years AFSCME had organized the police. The picture that emerges in Figure 6 is quite striking: organizations of city police officers existed in hundreds of cities across the United States before the legal upheaval of the 1960s. And this is likely an underestimate of the number of city police organizations. For example, the Chicago Tribune reported that “Chicago police have been organizing more or less secretly since early 1944, when …[the police chief] forbade Chicago police to join the union.”Footnote 78 Many police organizations were unaffiliated: a 1968 survey of cities with more than 10,000 in population revealed almost as many unaffiliated police organizations as FOP locals.Footnote 79 While our data include lists of cities in certain years where AFSCME had only organized the police (itself a sign that by the 1930s at least some unions were not opposed to organizing police), we have no way of knowing whether other AFSCME locals in our data also included police. Even with these data limitations, our data show clearly that police, too, had widespread organization before the laws.

Figure 6. Known Police Organizations by 1960.

We have so far shown that municipal employee organizations existed and were widespread, but one might ask whether or not they had a significant presence in these local governments. While we do not have membership data for the whole time series, we do know how many members the organizations had in 1938, 1939, and 1940. According to the Yearbooks, the organizations that were listed (IAFF, AFSCME, SCMWA, NCSA, and a few unaffiliated locals) counted 89,111 members in 1938. This grew to 103,966 in 1939 and 126,169 in 1940. From the city employment figures reported in the ICMA personnel data tables those years, employees in these organizations were 13.6 percent, 15.3 percent, and 17.7 percent of the total municipal employees in each year, respectively. These are sizable figures, especially considering that these are very early years (two decades before 1960) and not all employee organizations are covered here (police and most unaffiliated organizations being notable exclusions).

Other sources also report significant membership growth during this period for a variety of different organizations of local government employees. Godine writes that AFSCME and SCMWA/UPWA membership alone grew from approximately 47,000 employees in 1937 to over 126,000 in 1946.Footnote 80 IAFF reports that they had 25,000 members as of the 1920s, 65,000 in 1947, 72,000 in 1950, and 113,000 in 1963.Footnote 81 Archival records of NEA membership show that as of 1945, the mean ratio of NEA members to K-12 public school teachers in the states was 0.44.Footnote 82 Considered in combination with our limited data on city employee organization membership from 1938 to 1940, this suggests that many of these early local employee organizations did have meaningful membership.

These organizations were also highly politically active in working to secure benefits for their members, sometimes by using tactics similar to private-sector unions. Our data show there were ninety-four cities where some employees engaged in strikes between 1947 and 1951—even though striking in the public sector was highly contentious at the time. Public employee organizations in many of these cities also achieved agreements with their employers. As Wellington and Winter note, even when state laws did not enable collective bargaining,

A more permissive attitude was also demonstrated in actions taken by other branches of government. No matter what the formal legal structure seemed to dictate, many mayors, selectmen, and school boards began to bargain seriously with unions of their employees. Resolutions of municipal legislative bodies recognized unions, and other resolutions established terms and conditions of employment that in fact formalized bargains struck after arm's-length negotiations with unions. And municipal ordinances establishing formal procedures to govern collective bargaining were enacted.Footnote 83

How common were such agreements in years before the state laws? Case studies show that some local governments negotiated and upheld verbal agreements with their employees,Footnote 84 but there are no comprehensive data on such practices. However, using data from lists we acquired from the Yearbooks between 1945 and 1950, we find that 183 cities had some kind of written agreement in place during this period. Philadelphia’s 1939 agreement with AFSCME Local 222 was a highly publicized example. The agreement “for the purpose of avoiding industrial disputes,” covered the working conditions of employees in the Department of Public Works.Footnote 85 It “sets up hours of labor, provides against strikes and lockouts and confers the right on the union to bargain collectively for employees in the department.”Footnote 86 The Yearbooks do not provide details on what those agreements included or for which employees,Footnote 87 and most were almost certainly much more limited and tenuous for the employees than the contracts that were negotiated after state laws established a legal structure two decades later. Even so, these data suggest that by the late 1940s, many city organizations were not limiting themselves to civil service systems: they were seeking processes similar to collective bargaining, and in 183 cities, their employers had come to written agreements with them—without any legal requirement that they do so.

These instances of strikes and written agreements were also just the most visible and trackable cases of local employee organizations’ political activity. In an in-depth case study of the Building Service Employees International Union (BSEIU), an AFL union that represented janitors and maintenance workers in the public and private sectors (and was later renamed SEIU), Slater documents myriad ways in which its public-sector union locals engaged in politics to protect their members, increase pay, improve working conditions, and reach agreements with employers.Footnote 88 Their leaders and members lobbied public officials, made presentations at local public meetings, drafted proposed legislation, and helped to work the precincts in local elections in efforts to elect sympathetic public officials. During the 1930s, BSEIU’s roughly seventy locals of public-sector workers across the country:

strove to put in place friendly officials—both elected and appointed.… Where the BSEIU was strong, this strategy could work. When two unionists were elected to the school board in Minot, North Dakota, David [the BSEIU secretary] was elated. Perhaps confirming fears of union opponents, he expressed hope that in ‘coming elections, Brother members like yourself may be elected…so that the trade union movement will have full control of said School Board.’… Politicians did listen.… Sympathetic officials did make a difference.Footnote 89

One union leader said of his BSEIU local in Milwaukee that they “never found it necessary to have a signed agreement. We have made our working conditions and wage increases by dealing with the elected bodies, supporting the favorable members and bodies at election time and doing our best to defeat those who oppose us.”Footnote 90

In sum, well before states passed duty-to-bargain laws for government workers, hundreds of cities across the United States had organized employees. IAFF (and likely police) organizing surged in the late 1910s, and during the two decades after 1935, the number of city employee organizations exploded. Many of these organizations appear to have had a meaningful presence in city government. They struck for better working conditions and in some cases achieved agreements cementing their gains. Qualitative evidence shows that they got involved in local politics and sought to influence local elected officials. That the timing of all this coincided with the waxing and waning of private-sector union militancy and strength is notable. Moreover, the fact that police appear to have been well organized suggests that these unions were eager to include police as members, even if many elites were opposed to it.

Overlap between private- and public-sector organization

So far, we have focused on the presence of city employee organizations, the timing and geography of their spread, and their potential for influencing city government. Our analysis of these new data casts doubt on assertions that public-sector unions developed along a separate path from private-sector unions in the early twentieth century. As a next step, we more directly consider the overlap between these city employee organizations and private-sector unions. While we cannot use these data to test the theoretical mechanisms we laid out above, we take a preliminary step by beginning to evaluate whether the patterns we have found for city employees correlate with organizational patterns in the private sector.

In order to do this, we need a sense of the geography of private-sector unionization and whether there was overlap with city employee unions. However, city-level data on where private-sector unions were active are scarce; existing data on private-sector unions during this period mainly track union membership at a national level. We piece together three sources of data that include information about city-level organizing: two datasets gathered as part of the Mapping American Social Movements Project (MASMP), including (1) lists of Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) locals and strikes and (2) data on locals of seven CIO unions during the late 1930s and early 1940s,Footnote 91 and (3) a list of locals and membership of the International Typographical Union (ITU) in 1892.Footnote 92 By combining these data with the ICMA data on city employee unions (see online appendix), we can begin to assess the extent to which city employee unions were active in places that also had private-sector unions.

We start by focusing on the earliest years of city employee organizing. At the turn of the twentieth century, private-sector unions were already very active. We use the data on IWW locals and strikes as well as the list of ITU locals in 1892 to evaluate whether cities where public-sector unions emerged were places that also had active private-sector unions. The IWW data are useful here because IWW was active during the first two decades of the twentieth century; it was founded in 1905 out of opposition to AFL’s support of craft unionism. Many of the places in the MASMP dataset we acquired are very small towns or unincorporated places, but 178 cities that had IWW locals or strikes (or both) also appear in the early years of the ICMA data tables. Including the data on cities with ITU locals in 1892 is also helpful for two reasons: First, ITU had organized printers in over 200 cities by that time, including smaller towns, and so it gives us a fuller sense of private-sector unions’ geographic reach. Second, it provides some indication of AFL private-sector union presence in these cities (which the IWW data do not).

To measure the presence of public-sector organizations, here we focus on an indicator for whether the city had any known organization of city employees as of 1920. (This is mostly IAFF locals but also some unaffiliated and civil service organizations.) The lists of the 1938–1940 Yearbooks indicate eighty-nine cities of more than 10,000 in population that had public-sector organizations as of 1920. Bringing in the private-sector data, we find that of those eighty-nine, nearly two-thirds (fifty-nine) had an IWW local, an IWW strike, an ITU local, or some combination of the three. Considering that this is only tracking two unions of private-sector workers—and thus is far from representing the private-sector union movement as a whole—we interpret this as substantial overlap. As one might expect, many of the cities with either IWW or ITU and a city employee organization were large, but not all were. During the 1910s, for example, IWW and city employee organizations also overlapped in smaller cities like Hibbing, Minnesota, Great Falls, Montana, and Bellingham, Washington.

As we showed above, however, 1920 was still very early for city employee organizations. We would also like to examine the correlation between public- and private-sector unions in the years following the passage of the NLRA, when (as we showed earlier) there was a surge in city employee organizing. For this, we analyze data on private-sector CIO locals. Between the late 1930s and 1940s, total CIO membership numbered in the millions; it included (among others) coal miners, steel workers, auto workers, garment workers, electricians, and meat packers.Footnote 93 The MASMP data indicate which cities had locals of seven CIO unions between 1938 and 1949, including the United Auto Workers, the United Electrical Workers, the International Ladies Garment Workers, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, the International Woodworkers of America, and ITU. The inclusion of ITU is again helpful because it was affiliated with AFL until 1937 when it left to found CIO, and then rejoined AFL in 1944. So, although the MASMP data do not include AFL locals, the existence of an ITU local in a city might suggest that AFL had some presence there. Importantly, the city-level data on the seven CIO locals tracked in these data are not comprehensive, because they do not cover all CIO unions and entirely leave out AFL locals (other than ITU), but to our knowledge they are the only source of city-level union data available.

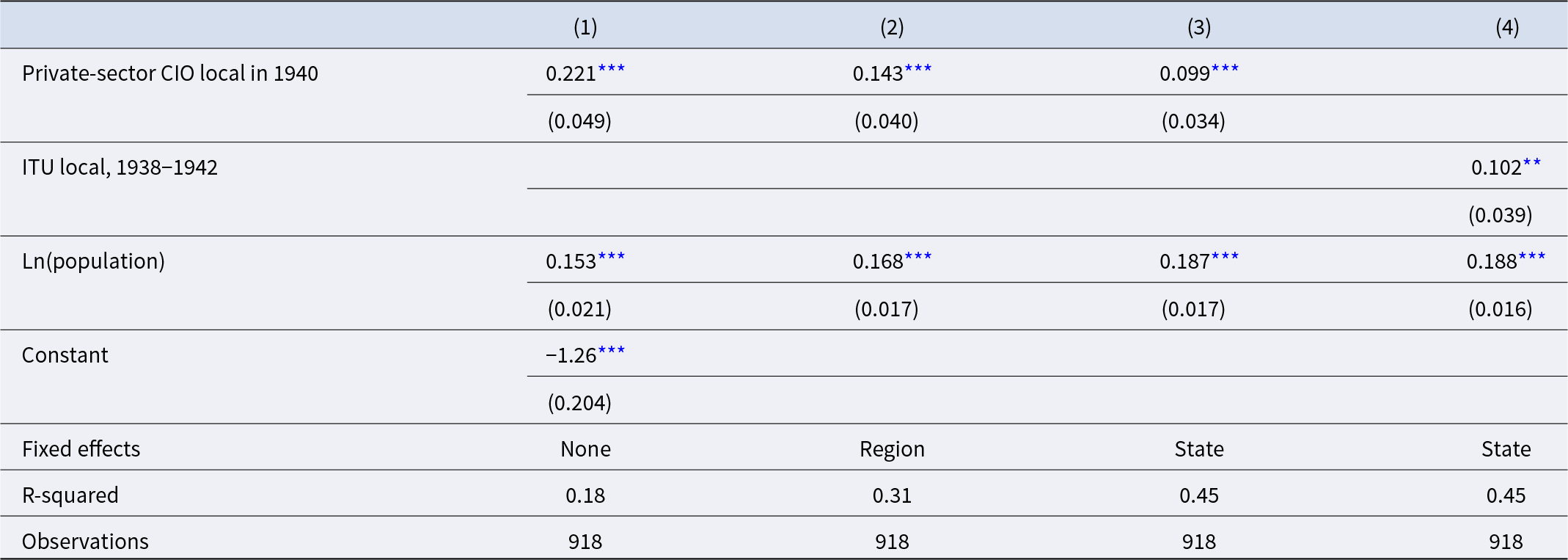

We begin in Table 1 with a snapshot of 1940. For that year, we know from the Yearbooks whether cities had an IAFF, AFSCME, SCMWA, or NCSA local (plus the few unaffiliated locals ICMA knew about). We include in the sample all cities that appeared in the ICMA personnel data tables for 1938–1940—the years in which the Yearbooks also provided employee organization lists. Moreover, 1940 is also the year in which the MASMP data are complete for all seven CIO unions it tracks. When we bring in data on city population in 1940, there are 918 cities in the sample. Table 1 presents a crosstabulation of these two variables for the 918 cities: an indicator for whether the city had a known city employee organization in 1940, and an indicator for whether the city had a known private-sector CIO local in 1940. Notably, when we look at the 549 cities with private-sector CIO locals, we find that a majority, 57 percent, had city employee organizations. Only 23 percent of cities without private-sector CIO locals had organized city employees.

Table 1. Overlap between Public- and Private-sector Unions in Cities

Table 1 also shows that ITU accounts for much of the 1940 CIO presence in many of these cities. Of the 918 cities, 562 had ITU locals at some point between 1938 and 1942. And the overlap between cities with city employee organizations and ITU was considerable: 317 of the 398 cities with a city employee organization in 1940 also had an ITU local during that time; only 81 cities with a city employee organization did not.

We expect that much of this overlap is due to city size, and that larger cities were more likely to have both private- and public-sector organizations for a variety of reasons. To explore whether private- and public-sector organization were correlated even in cities of similar size, we use OLS to regress the indicator of a city employee organization on the indicator of a known private-sector CIO local and logged city population in 1940. We cluster the standard errors by state.

The estimates, which should be interpreted as associations (not estimates of causal effects), are presented in Table 2. As we expect, larger cities were more likely to have city employee organizations in 1940: the estimated coefficient on logged population is positive and statistically significant. We also find that even accounting for city size, having at least one of these private-sector CIO locals in 1940 is positively and significantly associated with having a city employee organization. On average, a city with a known private-sector union was 22 percentage points more likely to have an organization of city government employees.

Table 2. City Employee Organizations in 1940

Notes: Standard errors clustered by state in parentheses.

* p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

Some of this relationship between CIO locals and public-employee locals is likely explained by regional variation: CIO locals were more common in the Midwest than other regions, for example. However, in Table 2, when we account for this regional variation by including regional fixed effects (column 2) and state fixed effects (column 3), we still find a positive, statistically significant association between the presence of a CIO local in 1940 and a city having organized municipal employees. Even within states, on average, cities with known CIO locals were 10 percentage points more likely to have city employee organizations.

In column 4, as a way of investigating the relationship between the spread of AFL and organized city employees, we replace the indicator of a CIO local with an indicator for whether the city had an ITU local at some point between 1938 and 1942. Of course, it is possible that ITU differed in meaningful ways from other AFL organizations, and that if we could measure all AFL locals, we might find a different relationship with public-sector organizations. However, we know that AFL was quite active in supporting public employee organizations—as we have said, IAFF and AFSCME were both chartered by AFL—and it seems reasonable that these locals would have been more likely to be established where private-sector AFL locals were active. The positive correlation we find between ITU locals and city employee organizations in column 4 suggests that may have been the case.Footnote 94

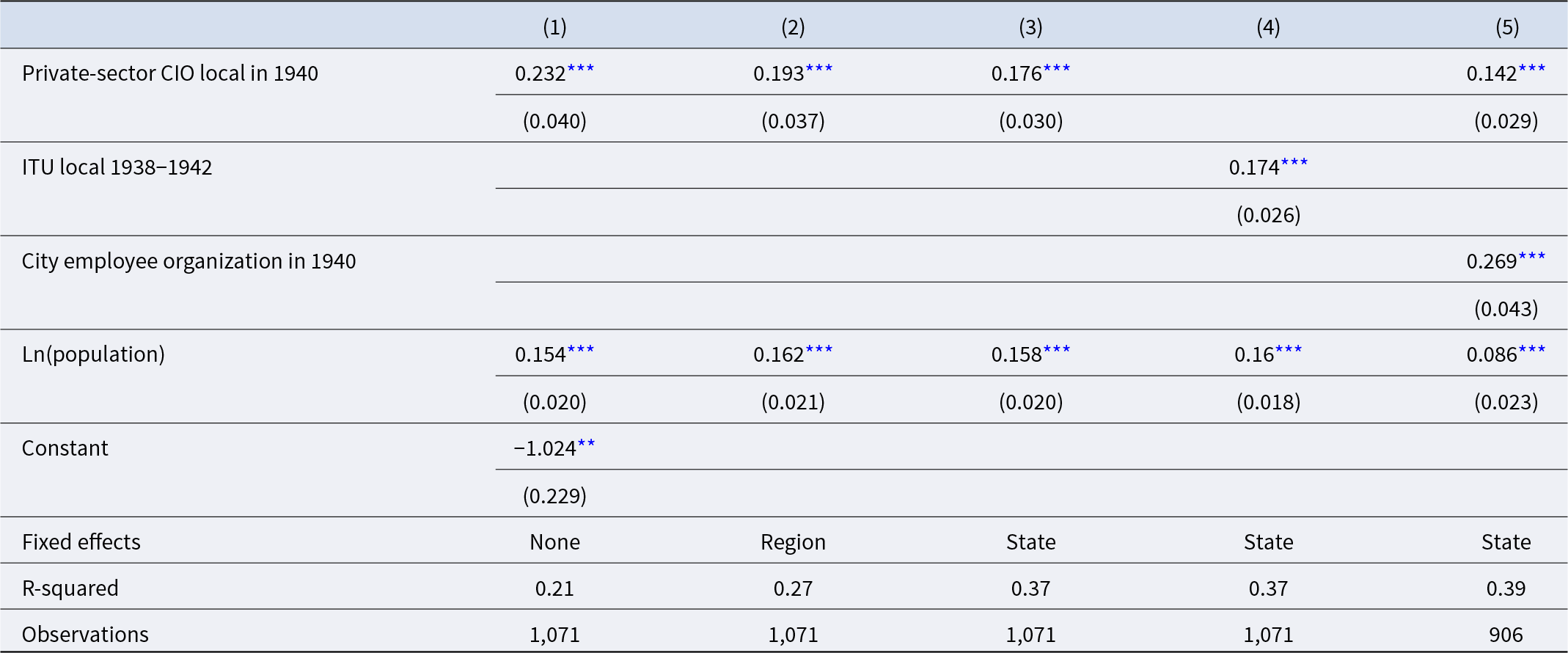

Next, we ask whether private-sector organization is related to public-sector organization in the future. In Table 3, we regress an indicator for a city employee organization in 1950 on the presence of a private-sector CIO local in the city 10 years earlier, plus logged city population in 1950. Column 2 adds regional fixed effects; column 3 adds state fixed effects. Throughout, we find that cities were much more likely to have public employee organizations in 1950 if they had also had private-sector CIO unions a decade earlier. Column 1 shows that on average, cities that had a CIO local in 1940 were 23 percentage points more likely to have a city employee organization in 1950. Even within regions and states and accounting for city population, cities that had had a CIO local or, specifically, an ITU local, in the previous decade were 17 percentage points more likely to have a city employee organization by 1950. In addition, when we add an indicator for whether the city had a city employee organization 10 years earlier (column 5), both the coefficients on the lagged city employee organization variable and the CIO local variable are positive and significant. Thus, public employee organization during the first half of the twentieth century was correlated with CIO unions in the private sector, suggesting that perhaps places with unions tended to beget more unions.

Table 3. City Employee Organizations in 1950

Notes: Standard errors clustered by state in parentheses.

* p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

We cannot say for sure what explains these associations, and many different explanations are possible. Moreover, the precise reasons for the relationship between private- and public-sector unions may have been different for different cities. Our quantitative analysis here—while important because it shows that such a relationship exists—cannot identify the extent to which different possible contributors gave rise to the overlap. However, others have highlighted that places with a strong union culture (thanks to the efforts of private-sector unions) were also more likely to develop public-sector unions. Steiber, for example, writes,

Leaders of public employee unions suggest that the organization of employees in municipal government can be influenced significantly by the strength and support of the labor movement generally. They believe that public employees are more likely to join unions in cities where labor has succeeded in organizing workers in the private sector than in nonunion cities.Footnote 95

In the theoretical logic we provided earlier, moreover, we laid out three plausible mechanisms (similar grievances, social ties, and direct organizational support) by which this could have occurred, and there exist contemporary accounts that provide support for each one.Footnote 96

First, there is ample evidence that many local government employee organizations were motivated by similar issues and grievances as their counterparts in the private sector. In 1928, the IAFF’s magazine ran a political cartoon depicting Santa Claus delivering his sack of gifts to a sleeping IAFF union member. Santa’s sack was labeled “The Benefits of Organization,” and among the gifts being delivered were “Better Hours” and “Better Pay.”Footnote 97 Levi writes that police officers “organize, as do privately employed workers, when they perceive their pay to be low, their working conditions poor, and the job pressures intolerable”Footnote 98 and has noted that “officers identified with the complaints of other workers and found inspiration in their achievements.”Footnote 99 The same was true of BSEIU, which “noted that the actual work of janitors in government buildings was the same as in private establishments” and urged school employees to organize to advance their collective well-being.Footnote 100

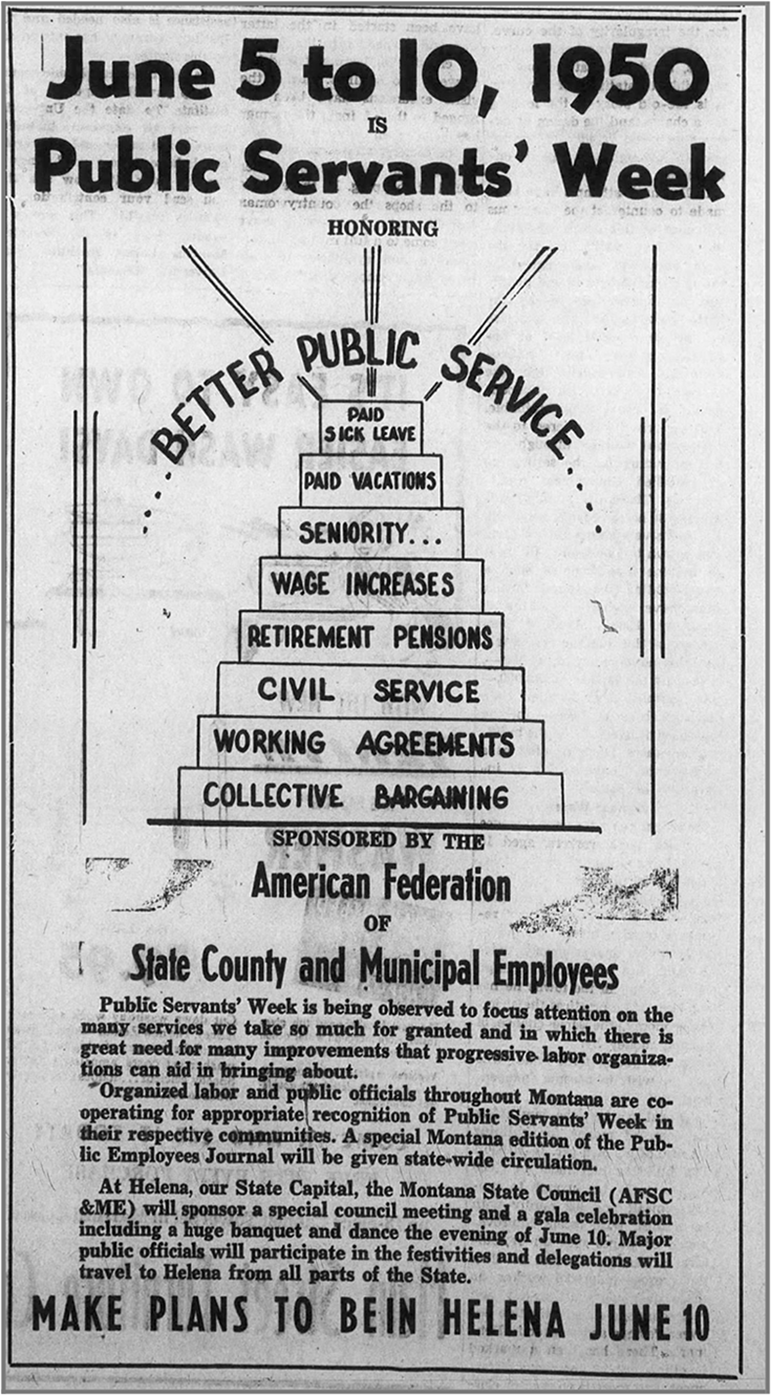

During the first half of the twentieth century, municipal employee organizations regularly worked to remedy these issues, advocating for pay increases, forty-hour workweeks, vacation days, sick leave, and protection from layoffs.Footnote 101 In addition, many promoted civil service implementation and protection,Footnote 102 and as early as 1919, some pushed for collective bargaining.Footnote 103 In 1950, AFSCME sponsored “Public Servants Week” in Montana, and the organization put out a full-page advertisement to explain their goals, which, the image indicates, were built on a base of collective bargaining (Figure 7).Footnote 104 In terms of their work and their grievances, therefore, many public-sector workers had a great deal in common with their private-sector counterparts.

Figure 7. AFSCME Advertisement of Goals, 1950.

In addition, there is evidence that public-sector organizations were highly socially engaged and that this is how ideas about unionism may have spread: not only were city employees likely embedded in the union networks Newman and Skocpol describe, but also city employee organizations contributed to that culture.Footnote 105 Levi reports that local public-sector unions “perform social functions as well. These include firefighters’ and police officers’ balls, or charter flights and tours for teachers.… Police associations set up athletic programs and contribute to camps for the needy.”Footnote 106 A survey of employee organizations in 1937 found that member-directed benefits, like social activities, were vital for improving morale and stabilizing membership.Footnote 107 The Minneapolis Star reported, “employees of the city health department will forget the cares and worries of relief matters and will dance at the Glenwood chalet tonight. The affair is sponsored by chapter No. 3, AFSCME No. 9.”Footnote 108 Writing in 1949, Kokomo, Indiana’s FOP Lodge President explained that bringing a circus to town, holding an annual dance, sponsoring a baseball team, establishing a Boy Scout troop, and other activities were intended to play a “small part in making Kokomo a better city to live in.”Footnote 109 In this sense, too, public- and private-sector unions may have been more similar than different.

There are also numerous examples of private-sector unions working with public-sector employees during this period. Case studies reveal instances in which private-sector unions actively organized or tried to organize city employees, such as efforts by the Teamsters to organize New York City sanitation workers and police officers.Footnote 110 Similarly, in Danville, California, in the early 1940s, IBEW sought to negotiate on behalf of the city electrical department.Footnote 111 In other cases, private-sector organizers, such as from the Teamsters, aided municipal employees’ votes to unionize.Footnote 112 In Camden, New Jersey, in 1944, the Morning Post reported that “men holding public office … are listening to the siren song of those union leaders who want public employees to join labor organizations.”Footnote 113

Private-sector unions also sometimes supported public-sector strikes. In 1910 in Spokane, for instance, IWW led a strike of firefighters who had been denied pay and then laid off.Footnote 114 Notably, nearly 100 unions also voted on sympathetic action with the famous Boston Police Strike of 1919.Footnote 115 In 1949, AFSCME placed an ad in the Port Huron Times Herald imploring readers, “Help us prevent a strike and to continue on the job of maintaining good roads for you. Express your support for our request to the road commission and your supervisor.”Footnote 116 In this case, Local 1039 was asking for the county commission to adopt rules governing layoffs, discharges, hearings, promotions, work assignments, seniority, and general working conditions. When their demands were not met, they struck. Tellingly, they were supported by a CIO rubber workers local during that strike.Footnote 117 The road workers returned to work after the County Road Commission agreed to negotiate to settle their differences.Footnote 118

In addition, many local government employee organizations were affiliated with and received support from the major labor federations, AFL and CIO, and public- and private-sector organizations regularly participated in the same labor boards, labor councils, and labor meetings.Footnote 119 Private- and public-sector unions also worked together politically, endorsing candidates and fighting for public policies.Footnote 120 Slater documents how AFL central labor councils helped public school teachers in their local organizing campaigns and used their political muscle to support the Seattle AFT’s electoral efforts.Footnote 121 Sometimes, moreover, local officials were sympathetic to public-sector unions because the local officials themselves were union members: In places like Chicago, Cheyenne, and St. Louis, when private-sector union leaders and members were appointed or elected to local government offices, they then assisted the organization of local government employees or reached agreements with them on working conditions.Footnote 122

It would seem then that private-sector union leaders, perhaps especially those operating at the subnational level, often did not see a distinction between their fight and that of municipal workers. As Levi writes, “At first glance, then, the unionization of public service workers is but an extension of the labor movement.”Footnote 123 Even the Indiana Republican Party saw public- and private-sector unions as parts of the same whole. In 1938, its platform stated:

The Republican party believes in the freedom, independence and the protection of American labor. Employees should have the right to deal collectively with the employer through representatives of their own choosing on wages, hours and working conditions without intimidation or coercion, and this right should be fully guaranteed and protected. We believe that employees of all branches of government, municipal, county and state, should enjoy the same hours of work and pay an hour when similarly employed, and be granted the same freedom of action, political and otherwise, as employees engaged in private industry. We believe in adequate laws to safeguard the lives and health of workers in all industries.Footnote 124

Thus, while there are other possible explanations for the correlation between local private- and public-sector organizations, these examples show that in some places, at least, similar inspiration and energy likely animated both the private-sector and the public-sector labor movements, and that they may have drawn on each other for strength.

Discussion

The unique development and decline of the American labor movement has long fascinated scholars in a wide range of disciplines, including sociology, history, economics, and political science.Footnote 125 Social scientists have focused on the decline of labor since the 1960s to help to explain rising economic inequality,Footnote 126 the influence of right-wing groups in the U.S. states,Footnote 127 and how the American heartland shifted to the Republican Party.Footnote 128 For the most part, when scholars of American politics study the labor movement, they almost always focus on the private sector. But government employees made up almost half of all union members in the United States in 2023,Footnote 129 even with the renewed momentum of private-sector unionization since 2021 and the adverse effects for public-sector unions of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Janus v. AFSCME. The literature examining unions of government employees has been largely separate from broader explorations of the American labor movement.Footnote 130

To the extent social scientists have considered the public and private sectors together, they have up to this point emphasized their distinctive developmental paths. In some ways, this is a natural and logical approach. Since the 1970s, when some reliable data on the two started being collected, the paths of private- and public-sector unions have been quite different. The recent trends mentioned above notwithstanding, private-sector union membership has been on a steady decline and remains very low. Public-sector union membership has been relatively more stable, and in many states—especially among local government employees like police officers, teachers, and firefighters—is quite high. Moreover, as we have explained, private- and public-sector unions faced distinct legal contexts and different levels of opposition to their organizational impetus—at least among political elites. In the small literature that exists on the development of public-sector unions, many scholars have pointed to the legal changes that started in the 1960s as one of the main catalysts of union growth in government. Prior to the 1960s, it has been argued, organizations of government employees floundered without supportive labor–management relations laws and struggled to solve their collective action problems while unions were thriving in the private sector.

We have shown that this account overlooks some key developments of the early twentieth-century labor movement. There were hundreds of city employee organizations by 1940. The vast majority of the city employee organizations that we know about were affiliated with major national labor federations, AFL or CIO. Their numbers continued to grow in the post-WWII period, such that by 1956, 71 percent of the cities with more than 10,000 in population had at least one city employee organization. In some cities, employees went on strike, and others negotiated written agreements with their city employers. Even police officers were organized in hundreds of cities by 1960. Opposition to police unions was widespread among elites (and to some extent the public as well), but it does not seem to have stopped police officers in cities from forming organizations.

The account our new dataset illuminates is one of extensive city employee organizing long before the 1960s: by IAFF and some unaffiliated organizations prior to 1920; by the explosive growth of AFSCME and SCMWA in the years immediately following the passage of the NLRA, in spite of the fact that government employees were excluded from the legislation; and throughout the period of post-WWII militancy of private-sector unions. Government unions grew and expanded when private-sector unions were most active, and these patterns have not been documented beyond the qualitative scholarship of a small number of labor historians.

We have also presented some theoretical logic for why and how public-sector organizing would be linked to private-sector unions. We propose that while the favorable state legislation of the late 1960s to early 1980s no doubt helped public-sector unions in myriad ways, city employees might also have overcome their collective action problems with the encouragement and organizational assistance of other unions—including private-sector unions. We highlight the similarity in the work and grievances of many private- and public-sector employees. We theorize that many city employees were embedded in social networks with and had community ties to private-sector employees who were in unions. And we point out that not only would city employees like firefighters and sanitation workers likely have been a part of the union culture documented by Newman and Skocpol,Footnote 131 but they also contributed to that culture themselves. When we consider the circumstances from the standpoint of workers and their organizations, we begin to see that between private- and public-sector labor, there was more the same than was different.

Perhaps ironically, even as some scholars have lamented how the absence of supportive legislation devastated the development of public-sector unions at a time when private-sector unions thrived (thanks to their favorable federal legislation), it may be that public-sector organizations actually needed the laws less than the private sector. Presumably, many private-sector employers had to be forced into collective bargaining with their employees’ unions by the legal mandate. By contrast, in the thousands of local democracies across the United States, organizations of firefighters, police officers, janitors, and sanitation workers could try to influence their employers through local elections. Today, electoral pressures contribute to the continued organizational strength of public-sector unionization.Footnote 132 Because of this, it may well be that there was overall less resistance to the pursuits of employee organizations in local governments than there would have been in an industrial plant or a mine absent the laws. An important difference between city employee unions and private-sector unions, then, is that city employee unions sought favorable policies not from profit-maximizing firms but rather in local democracies where management was more susceptible to political pressure.

In short, there are good reasons to believe that public- and private-sector organization might be correlated during this period. We find that they are. Numerous examples show how private-sector unions either helped city employees organize or directly tried to organize city employees themselves. And using data on the location of private-sector CIO locals around 1940, we find that the presence of a CIO local is strongly associated with a city having an employee organization—both contemporaneously and 10 years later.

There is much that remains to be studied, and we hope that the dataset we have assembled will enable and inspire more research on the questions that arise from our findings here. For example, while we have theorized a number of ways in which private- and public-sector unions may have worked in concert and found evidence consistent with that assertion, our data and design do not allow us to determine whether there was a causal effect of unions in one sector on the development of unions in another sector. Nor does this article systematically investigate any particular mechanism by which the overlap we find occurred. It is possible, for instance, that some other characteristics of these cities made them more or less conducive to union organizing in both the private and public sectors. For instance, perhaps cities with larger immigrant populations from European nations with powerful labor movements were more likely to see organizations develop in the public and private sector alike. Alternatively, it is possible that urban political machines (which governed many of the cities that were home to large immigrant populations) supplanted or suppressed labor organization in both sectors.

We also think there is much to be learned from more extensive research on where, why, and when city employee organizations formed, such as whether the racial, ethnic, and/or gender composition of the city workforce played a role. Today, Black workers are employed in the public sector at a higher rate than white workers.Footnote 133 Moreover, the public-sector labor activism of the 1960s was clearly intertwined with the civil rights movement; notably, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968 in Memphis, where he had travelled to support an ongoing, tumultuous AFSCME strike. Our dataset does not contain information about the demographic composition of these early public organizations, and so we cannot use it to investigate the extent to which early city employee unions included racial or ethnic minorities or women. In the online appendix, however, when we account for the share of city residents who were Black or immigrants, we do not find significant associations with the presence of early city employee organizations (in the regressions with regional or state fixed effects). Future scholarship should explore this more fully, by developing theory about how race, ethnicity, and gender might have affected early public-sector union formation, as well as by identifying new sources of data on the demographic composition of these unions.

Our findings also raise interesting questions about how varying economic and political conditions might have affected public employee organizing, both over time and across space. It is broadly understood that the labor market context affects the bargaining power of workers and that private-sector union militancy has tended to wax and wane with the tightness of labor markets. Labor history also suggests that organizing momentum can be encouraged or dampened by political factors: the 1920s, for example, was a relatively quiet decade for labor activism and also a period of pro-business government at the national level, whereas organizing surged during the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt.Footnote 134 Given the patterns we reveal in Figures 1 and 2, the timing of public-sector organizing may have been affected by similar factors.

We show here that there was a correlation between public- and private-sector organizing, but a number of questions follow. Were public-sector unions more likely to form in places and times of high demand for government workers? How was public employee organizing affected by the extent to which those workers had alternative employment opportunities, or the extent to which there were alternatives to government provision of a service? And was public employee organizing more likely under labor-friendly mayors, city councils, and school boards? These are important questions that we hope will inspire further local-level data collection.

In addition, future research should investigate the consequences of employee organizations including whether and how public-sector unions contributed to local culture, as Newman and Skocpol have shown for private-sector unions.Footnote 135 There is also much to be learned from more extensive research on how they engaged in local politics, such as in elections, and what effects they had on policy, including employment, compensation, and the structure and operation of municipal police and fire departments. Future research should also go beyond the existing case studies to investigate whether these organizations influenced state public-sector labor laws of the 1960s–1980s.