The polygraph has been proposed as a useful tool in the treatment and supervision of sex offenders (Reference BlasingameBlasingame, 1998; Reference Grubin, Madsen and ParsonsGrubin et al, 2004). Proponents argue that it provides clinicians with more reliable sexual histories, more complete and accurate offence descriptions, and a greater likelihood of identifying high-risk behaviours, enabling intervention to take place before re-offending re-offending occurs. Many American states require sex offenders to undergo regular polygraph examinations as a condition of probation or parole, and similar measures are being considered in England. Although research conducted in so-called post-conviction settings is supportive, the focus has been on utility rather than accuracy. However, if polygraphy is not particularly accurate, then utility will be compromised as those examined come to believe that the polygraph does not work. In the study reported here, offenders’ self-report is used to assess the accuracy and utility of post-conviction polygraph testing.

METHOD

Participants

Three hundred and twenty-one sex offenders participating in community-based treatment programmes in the American state of Georgia were approached, of whom 176 (55%), including 3 women, agreed to take part. Ages ranged from 18 years to 82 years (mean 40, s.d.=12.6). Of these 176 participants, 144 were White (82%), 28 were African American (16%) and 4 were from other ethnic backgrounds. One hundred and fifty (85%) of the offenders had been convicted of contact sexual offences, of whom 137 (78%) had offended against child victims, 12 (7%) against adult victims and 1 against both. Sixteen (9%) participants were convicted of non-contact sexual offences, 8 (5%) were awaiting trial and 2 (1%) had not been convicted of a sexual crime. The mean length of time in sex offender treatment was 23.5 months (s.d.=23, range 1–120).

Risk

One hundred and sixty-one participants were scored on Static-99 (Reference Hanson and ThorntonHanson & Thornton, 2000), a widely used actuarial instrument that provides an estimate of the probability of sexual and violent recidivism for adult males (the other 15 individuals could not be scored on this instrument). Ten individuals were scored by two raters unaware of each other's results, with perfect agreement between them. Based on Static-99 ratings for these 161 individuals, 93 participants (58%) were assessed as low risk, 46 (29%) as medium-low risk, 19 (12%) as medium-high risk and 3 (2%) as high risk.

Personality

The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO; Reference Costa and McCraeCosta & McCrae, 1992) is a self-report questionnaire that assesses normal personality dimensions based on a five-factor model: neuroticism (N), extraversion (E), openness to experience (O), agreeableness (A) and conscientiousness (C). Valid NEO profiles were obtained for 152 participants (86%). Overall, scores were in the high range for neuroticism (mean 87, s.d.=21), the average range for extra-version (mean 101, s.d.=16) and agreeableness (mean 120, s.d.=15) and in the low range for openness (mean 100, s.d.=15) and conscientiousness (mean 114, s.d.=17).

IQ

The second edition of the National Adult Reading Test (NART–2; Reference Nelson and WillisonNelson & Willison, 1991) was used to provide an estimate of IQ. Thirteen participants did not complete this test. For the remaining sample the mean IQ was 102 (s.d.=11.9, range 75–128).

Previous experiences of the polygraph

A 12-item survey, the Previous Experiences of the Polygraph Questionnaire (PEPQ), was developed for the study to gather descriptive information about participants’ previous experiences and perceptions of the polygraph (the PEPQ is included as a supplement to the online version of this paper). The questionnaire is divided into three sections. The first section addresses false positive and false negative rates, false admissions and the use of countermeasures; the second addresses the extent to which the participants consider the polygraph to be helpful in assisting them to avoid risk behaviours and re-offending and to engage in treatment; and the third section investigates the participants’ perceptions of polygraph accuracy (further information available from the author on request).

Procedure

All participants were taking part in treatment programmes in which polygraphy was a condition of participation, and were approached while attending their regular treatment groups. They were informed that the purpose of the research was to investigate the value of the polygraph in a post-conviction context. They were assured of confidentiality, and all gave their signed informed consent. Participants were seen on a single occasion for up to 60 min, during which they completed the PEPQ, either by themselves or with other participants. They were then interviewed about their present circumstances and past experiences of the polygraph; the NART–2 was administered at this time.

Ethical approval

The study was submitted to the Northumberland, Tyne and Wear research ethics committee. Because the study was carried out in the USA it fell outwith the committee's remit, but its memebrs indicated that it would have been considered favourably. This was taken into account by each treatment centre in its review of the protocol.

RESULTS

Self-reported accuracy

Altogether, 174 offenders provided information about previous polygraph tests. Of these, 126 (72%) reported completing a total of 263 polygraph tests while on probation; the remaining 48 individuals (28%) had not yet had their first polygraph examination, but were scheduled to do so. Participants reported that in 225 (86%) of their completed tests they had told the truth, and that they were deceptive in 38 (14%); according to them, the polygraph outcome on these tests was ‘no deception indicated’ in 197 (75%) and ‘deception indicated’ in 66 (25%) (Table 1), giving a false positive rate of 15%, a false negative rate of 16% and an overall accuracy of 85%. Based on self-report, the specificity of the tests (correctly detecting truthfulness) was 85% and the sensitivity (correctly detecting deception) was 84%. It can also be seen from Table 1 that in the 197 tests in which offenders reported the outcome as being ‘no deception indicated’, they said that this was correct in 191 (97%) of cases (the negative predictive accuracy), whereas in the 66 ‘deception indicated’ tests, this was correct in only 32 cases (48%) (the positive predictive accuracy). The deceptive individual is 5.57 times (95% CI 3.97–7.82) more likely to be labelled deceptive than is the truthful one, whereas the truthful individual is 5.37 times (95% CI 2.57–11.23) more likely to be labelled truthful than the deceptive one. The receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (AUC) is 0.85.

Table 1 Self-reported accuracy rates for post-conviction polygraph examinations based on number of tests

| Self-report | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Polygraph test result | Deceptive | Truthful | Total |

| Deception indicated | 32 | 34 | 66 |

| No deception indicated | 6 | 191 | 197 |

| Total | 38 | 225 | 263 |

When the 126 individuals who had taken polygraph tests are considered rather than the number of tests they reported completing, 27 (21%) stated that they had been wrongly reported as deceptive when telling the truth on at least one occasion, and 6 (5%) that they had been wrongly reported as being truthful when they had in fact been lying (Table 2). There was no overlap between these individuals.

Table 2 Self-reported accuracy rates for post-conviction polygraph examinations based on individuals tested, some tested more than once

| Self-report | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Polygraph test result | Deceptive | Truthful | Total |

| Deception indicated | 29 | 27 | 56 |

| No deception indicated | 6 | 64 | 70 |

| Total | 35 | 91 | 126 |

False positive cases

Individuals who reported telling the truth but were wrongly labelled as deceptive (false positive; n=27) were compared with those who said they had been correctly classified as telling the truth (true negative; n=64), as well as with those who reported being correctly detected as being deceptive (true positive; n=29). Relevant variables were grouped into two categories: historical (age, ethnic origin, previous psychological and psychiatric history, educational attainment, number of previous polygraph tests, and risk) and psychological (personality, IQ). Univariate analyses did not yield any significant difference between the groups in respect of any of these variables.

False negative cases

Individuals who claimed they had been deceptive but were classified as ‘no deception indicated’ (false negative; n=6) were compared with those who reported being deceptive but accurately labelled as such (true positive; n=29), and with those who said they had been correctly labelled as non-deceptive (true negative; n=64). Univariate analyses did not yield any significant results.

Utility

Of the 126 offenders who had been polygraph tested, 114 fully completed the PEPQ. Of these 114, 50 (44%) reported that they were more truthful with their probation officers and treatment providers than they otherwise would have been because of the polygraph; 39 (34%) reported that it assisted them in being more truthful about their behaviour to family and friends. Similar results were found in relation to the 45 participants who had not yet been tested and fully completed the PEPQ, with 20 (44%) and 16 (36%) respectively indicating that the expectation of a polygraph test increased their disclosures to probation officers and to family and friends.

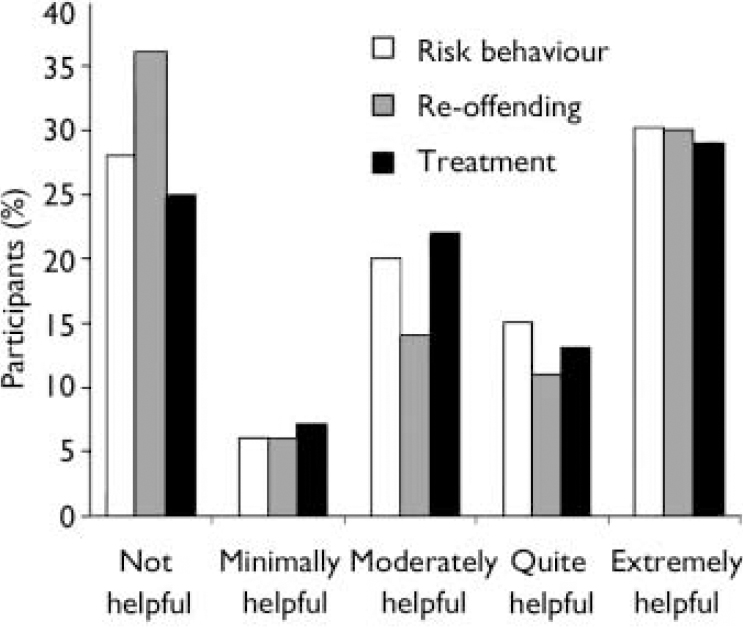

Regarding behaviours associated with offending, 71 (56%) of the 126 individuals who had previously been polygraph tested reported that the polygraph was moderately to extremely helpful in assisting them to avoid re-offending, re-offending, 80 (63%) that it was useful in assisting them to avoid risk behaviours and 84 (67%) that it was generally helpful in respect of treatment; similar responses were given by those awaiting their first examinations (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Participants’ perception of the helpfulness of polygraph testing with avoiding risk behaviours and re-offending and with engagement in treatment (n=116 men previously tested and 45 men awaiting polygraph examination).

Information was available for 173 men regarding specific risk behaviours: 57 individuals (33%) reported that they were less likely to masturbate to deviant (offence-related) fantasies, 53 (31%) that they were less likely to have contact with children or potential victims, 47 (27%) that their use of drugs and alcohol was reduced, and 44 (25%) that they were less likely to use or buy pornography. However, a significantly greater proportion of those who had undergone polygraph testing, compared with those awaiting their first test, reported that they were less likely to visit places to view children (37 ν. 5, χ2=5.9, d.f. 1, P=0.01) and to engage in other more general risk behaviours (18 ν. 1, χ2=4.2, d.f.=1, P=0.04).

Information was available for 165 men regarding their perception of the accuracy of the polygraph. No difference was found between participants who had previously had a polygraph test and those who had not. Overall, 16 participants (10%) considered it to be no more accurate than chance, 15 (9%) ‘slightly’ accurate, 73 (44%) ‘moderately’ accurate and 63 (38%) as being ‘quite’ to ‘extremely’ accurate.

Sanctions

Twenty-seven (22%) out of 121 men who had completed a post-conviction polygraph test reported experiencing a direct sanction because of its result or a disclosure made during the test; the most common of these involved having to address additional issues in treatment or supervision (78%), although two individuals claimed that their treatment was terminated and two that their contact with their families was reduced. There was no relationship between having experienced a sanction and claiming to have had a false positive result (χ2=3.07, d.f. 1, P=0.08).

To test whether having been sanctioned or erroneously classified (false positive or false negative) affected the participant's perception of the polygraph's utility, an overall ‘helpfulness’ variable was created by combining the scores of the three utility scales. No difference in perception of utility was found between those who experienced sanctions and those who did not (t (111)=0.38, P=0.7), nor was there a difference between those who reported being false positives and true negatives, or between the false negatives and true positives.

Countermeasures and false admissions

Only two participants (2%) claimed to have used drugs to beat the polygraph. Both also claimed to have previously been deceptive without being detected. Twelve participants (10%) reported making false admissions regarding their behaviour at some stage during a post-conviction polygraph test, of whom only 5 claimed to have been wrongly labelled as being deceptive. The main reasons given for false admissions were the fear of getting in trouble with probation officers in three cases, and feeling pressured by the polygraph examiner in another three cases. Other reasons were wanting to make a good impression, ‘confusion’, ensuring that the test was passed, and wanting to demonstrate commitment to therapy.

A significant difference was found when a one-way between-groups multivariate analysis of variance was performed using the five NEO domain scores as dependent variables and ‘having made a false admission’ as the independent variable (F (5,96)=2.46, P<0.01). When results for the dependent variables were considered separately, two reached statistical significance using a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level of 0.01: neuroticism (F (1,102)=10.08, P<0.01) and conscientiousness (F (1,102)=7.85, P<0.01), with the false confessors having higher levels of neuroticism (104 ν. 84) and lower levels of conscientiousness (101 ν. 116).

DISCUSSION

Our study explores the experiences of community-based sex offenders required to undergo regular post-conviction polygraph examinations. Broadly speaking we found that the majority of sex offenders reported polygraphy to be helpful in terms both of treatment and of avoiding risk behaviours and re-offending. These findings, however, are based on the responses of the 55% of programme participants who agreed to take part in the study, and it is possible that the other 45% might have had very different views on the value of polygraph testing.

Utility of post-conviction polygraph testing

Our results are consistent with other studies examining the utility of post-conviction polygraph testing in sex offenders, which typically report fuller histories of deviant sexual behaviour, admissions of previously unknown offences and victims, and increased disclosure of high-risk behaviours (Reference Emerick and DuttonEmerick & Dutton, 1993; Reference Ahlmeyer, Heil and McKeeAhlmeyer et al, 2000; Reference Harrison and KirkpatrickHarrison & Kirkpatrick, 2000; Reference Hindman and PetersHindman & Peters, 2001; Reference Grubin, Madsen and ParsonsGrubin et al, 2004; Reference Madsen, Parsons and GrubinMadsen et al, 2004). It has been argued that increased disclosure by offenders enables improved identification of treatment targets, encourages engagement by helping to overcome denial, and assists offenders in adhering to relapse prevention plans (Reference BlasingameBlasingame, 1998; Reference English, Jones and PatrickEnglish et al, 2000; Reference Grubin, Madsen and ParsonsGrubin et al, 2004). Our findings indicate that polygraphy can have a therapeutic role as well as the more usually perceived function of ‘detecting lies’. Indeed, confirmation that an individual is being honest in treatment and supervision, particularly in contexts where risk is a real issue, can be a critical element in the treatment process.

Accuracy

Although an emphasis on utility in post-conviction settings is understandable, polygraph accuracy cannot be ignored. If those tested do not believe that polygraphy works, they will be less likely to disclose relevant information during a test. In addition, a knowledge of accuracy rates is required to make sense of apparent deception in the absence of disclosure. Those tested as well as those who rely on test results must have confidence in the validity of the technique if it is to be viable clinically.

The literature contains conflicting accounts of polygraph accuracy, with many studies criticised for their methodological weaknesses (Reference FuredyFuredy, 1996; Reference LykkenLykken, 1998; Reference Cross and SaxeCross & Saxe, 2001). A recent definitive review carried out by an expert panel appointed by the US National Academy of Sciences concluded that the best estimate of polygraph accuracy falls between 81% and 91% (National Research Council, 2002). However, none of the research reviewed in the National Academy report examined the accuracy of polygraphy when used in post-conviction or therapeutic contexts. We are aware of only one study that has investigated polygraph accuracy in a post-conviction setting (Reference Kokish, Levenson and BlasingameKokish et al, 2005). In this research 95 sex offenders taking part in treatment groups in California and assured of anonymity were asked about the accuracy of the 333 polygraph tests they had completed. Eighteen individuals claimed to have been wrongly accused of deception on 22 tests, and 6 individuals to have been wrongly labelled as non-deceptive on 11 tests, leading the researchers to conclude overall accuracy in their programme of 90%. From the data they presented, it is not possible to calculate specificity, sensitivity or predictive values. We made use of methodology similar to that of Kokish et al (Reference Kokish, Levenson and Blasingame2005). Our results, indicating an accuracy rate of 85% in detecting truth-telling and 84% in detecting deception, are similar to the rates found in the California offenders. Although this approach depends on the uncorroborated self-report of participants with no means of comparing their accounts with actual test outcomes, the reported accuracy rates in both samples are consistent with the National Academy of Sciences estimate of polygraph accuracy. The offenders themselves also perceived the accuracy of the polygraph to fall within this range, with the majority rating it as ‘moderately’ to ‘extremely’ accurate.

Accuracy in a clinical context

Although overall accuracy appears good, interpreting this in respect of specific test outcomes is not straightforward. Although the negative predictive rate (the likelihood that the person tested is telling the truth when the examiner concludes ‘no deception indicated’) of 97% is very high, the positive predictive rate (the likelihood that the person is lying when the examiner concludes ‘deception indicated’) of 48% is much less good. This does not mean, however, that polygraph outcome in detecting deception is no better than chance: the AUC of 0.85 suggests good predictive accuracy, as does the finding that the deceptive individual is over five-and-a-half times more likely to be labelled deceptive than is the non-deceptive non-deceptive individual.

The low positive predictive value may partly reflect self-presentation biases (deceptive offenders may be more likely to claim that the polygraph was wrong when caught out and less likely to disclose having ‘beaten’ it), but more relevant is the relatively low base rate of deception reported by the sample, with this admitted in only 38 of 263 tests (14%). The importance of the base rate of deception in the group of people being tested was highlighted in the National Academy of Sciences review, who observed that where base rates of deception are low, even a highly accurate test will produce more false than true positives (National Research Council, 2002). It is one of the primary reasons the review did not support the use of polygraphy in security contexts, where the base rate of deception is likely to be low (one hopes there are few spies in federal agencies); the review suggested that polygraphy only becomes viable when the base rate of deception exceeds 10%. Even based on self-report, it would appear that a deception rate of over 10% is likely to be the case within sex offender treatment programmes. However, it should also be noted that in post-conviction testing the emphasis is less on ‘passing’ or ‘failing’ the polygraph, and more on the facilitation of disclosures relevant to supervision and treatment. Getting it ‘wrong’ in a post-conviction test is of much less consequence than a wrong result in a criminal investigation or a security screen, where much more reliance may be placed on the examination.

False positives, false negatives, disclosures and false disclosures

None of the variables we tested distinguished offenders more likely to have false positive or false negative results. Waid et al (Reference Waid, Orne and Wilson1979) suggested that socialisation may be associated with false negative errors. Although socialisation has been related to the neuroticism and conscientiousness domains of the NEO (Reference Costa and McCraeCosta & McCrae, 1992), neither of these characteristics distinguished false negatives from true negatives or true positives in our study. Conversely, in the context of a polygraph examination some individuals may feel pressured to make untrue admissions. Nine per cent of the offenders in our study, and 5% in the study by Kokish et al (Reference Kokish, Levenson and Blasingame2005), claimed to have done so, suggesting that although the incidence of this is not high, it is of relevance. We found that high neuroticism and low conscientiousness scores characterised those who reported making false admissions; the former is associated with pervasive feelings of guilt, fear and embarrassment as well as high impulsivity, and the latter with being less scrupulous and reliable. This suggests that individuals who falsely disclose may be more emotionally disturbed in general, and more impulsive; in difficult interview situations, they may cope by ‘confessing’. Six of those who reported making false disclosures in our study attributed this to either a fear of getting into trouble with their probation officers or feeling pressured by the polygraph examiner.

In summary, our findings support the view that post-conviction polygraph testing is a useful adjunct to the treatment and supervision of sex offenders in the community. Accuracy rates as reported by offenders who have undergone polygraph examination appear to be of a sufficiently high level to maintain the utility value of the tests.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Post-conviction polygraph testing is a useful adjunct to the treatment and supervision of sex offenders in the community.

-

▪ The accuracy of polygraph testing as repor reported ted by offenders is similar to that found in studies carried out in other settings.

-

▪ A small proportion of individuals may make false disclosures.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The findings are based on the self-report of offenders, with no means of comparing their accounts with actual test outcomes.

-

▪ Self-presentation biases might have influenced self-report of false positives and false negatives.

-

▪ Forty-five per cent of those approached to take part in the study declined to do so.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding from the National Health Service National Programme on Forensic Mental Health Research and Development. However, the views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not of the Programme nor of the Department of Health.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.