Alzheimer's disease has a rapidly increasing incidence rate, with an expected doubling of patients every 20 years.Reference Prince, Ali, Guerchet, Yu-Tzu and Prina1 Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia after Alzheimer's disease.Reference O'Brien and Thomas2 The recent prevalence of Alzheimer's disease was estimated at 4.2% in the worldwide population above age 65 years,Reference Fiest, Roberts, Maxwell, Hogan, Smith and Frolkis3 whereas about 1% have a diagnosis of vascular dementia.Reference Rizzi, Rosset and Roriz-Cruz4 In particular, the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease is not yet fully understood. Because of its enormous personal and global impact, modifiable risk factors need to be identified as soon as possible. The association between anxiety and cognitive decline/dementia has been discussed recently.Reference Gulpers, Ramakers, Hamel, Kohler, Oude Voshaar and Verhey5 Various anxiety-associated factors like inflammation and oxidative stress are linked to the pathogenesis of both types of dementia.Reference Machado, Herrera, de Pablos, Espinosa-Oliva, Sarmiento and Ayala6 Anxiety is characterised by enduring anticipation and permanent neurotoxic distress.Reference Pary, Matuschka, Lewis, Caso and Lippmann7 Especially in old age, neurons are susceptible to the damaging effects of glucocorticoids.Reference Fuxe, Diaz, Cintra, Bhatnagar, Tinner and Gustafsson8 Therefore, the occurrence of anxiety might be a preventable risk factor for dementia when still young; however, bearing in mind the long preclinical phase of Alzheimer's disease,Reference Dubois, Epelbaum, Santos, Di Stefano, Julian and Michon9 it could accelerate a destructive chain reaction at an advanced age.Reference Prenderville, Kennedy, Dinan and Cryan10 We aim to explore the significance of this association by pooling the evidence yielded from longitudinal studies with a minimum follow-up of 2 years and observance of healthy samples to avoid reversed causality and confounding factors. The scope of this systematic review comprises anxiety disorders, unspecified anxiety symptoms and trait anxiety. For the first time, we not only investigate the predictive value of a broad spectrum of anxiety phenomena, but also differentiate between Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia.

Method

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement,Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman11 the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statementReference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie12 and the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions.Reference Higgins and Green13

Search strategy

We searched the databases MEDLINE, all databases from the Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL and ALOIS for relevant publications on 16 June 2016 and updated the procedure on 16 June 2017 and 12 January 2018. We did not set any constraints. The strategy combined related terms of anxiety and dementia (Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.173). Reference lists of relevant reviews were also screened. The search was rounded up by contacting eight leading authors to identify unpublished data.

Selection criteria

Studies were eligible if they were observational cohort studies or case–control studies with a period of at least 2 years. We only included original work. References were excluded if there was no evidence of any psychological or neuropsychological test or psychiatric diagnostics. Anxiety needed to be assessed distinctly. We further excluded descriptive studies and qualitative research. Participants had to be free of cognitive impairment, systemic and any other psychiatric disorders than anxiety disorders at baseline. Diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia needed to be based on diagnostic criteria according to the DSM-514 or ICD-10.Reference Sartorius15 Whenever studies referred to the same cohort, a longer follow-up or look-back period was the decisive factor, ahead of population size.

Data extraction

A physician (E.B.) and a psychologist (C.L.O.R.) screened abstracts independently. Methodological, clinical and statistical data were collected extensively (Supplementary Appendix 2). Missing data regarding study characteristics, assessment of quality and meta-analysis were requested from the authors. Included studies were rated with the weight of evidence frameworkReference Gough16 (Supplementary Table 1). It is based on the evaluation of three criteria: methodological quality, methodological relevance and topical relevance. Relevance criteria are customised to match the specific review question. Quality indicators of non-randomised studies were evaluated by use of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.Reference Wells, Shea, O'Connell, Peterson, Welch and Losos17 Risk of bias was rated with the Risk of Bias in Non–randomised Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool.Reference Sterne, Hernán, Reeves, Savović, Berkman and Viswanathan18

Statistical analysis

We used the generic inverse variance method with a random-effects model to calculate the pooled time to Alzheimer's disease and incidence of vascular dementia.Reference Schwarzer, Carpenter and Rücker19 Whenever available, the reported hazard ratios and odds ratios from fully adjusted models were preferred. Distinct risk estimates were synthesised in separated groups with 95% confidence intervals.Reference Schwarzer, Carpenter and Rücker20 Binary or continuous data of the independent variable were provided. The sensitivity analysis explored the effect of pooled studies with lowest risk of bias. Potential publication bias was investigated by inspecting funnel plots. R software was used for the conduction of all analysis and graphics (version 3.4.0).21, Reference Schwarzer22

Results

Study selection

From 16 556 records identified by systematic database search (n =16 360) and hand-search (n =196), 13 620 records were left after de-duplication (Fig. 1), and 641 full-texts were checked on inclusion. Some titles were not available (Supplementary Appendix 3). Ten articles met inclusion criteria,Reference Burke, Maramaldi, Cadet and Kukull23–Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 with two studies being eligible for both outcomes.Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30, Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 One study was identified by checking the reference lists.Reference Jessen, Wolfsgruber, Wiese, Bickel, Mosch and Kaduszkiewicz27 We exchanged one paperReference Burke, Maramaldi, Cadet and Kukull23 because of a more recent version ahead of publication.Reference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24 Only nine risk ratios from nine studies were left for quantitative analysis because of inappropriate risk ratios with regard to the meta-analysis. Bruijn et al Reference Bruijn, Direk, Mirza, Hofman, Koudstaal and Tiemeier25 analysed data about unspecified anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders from the same participants, who had been assessed at two different follow-ups. The results referring to the earlier part of the study were selected for quantitative analysis.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. * indicates that two studies were eligible for both outcomes.

Anxiety and risk of Alzheimer's disease

Study characteristics

Study characteristics and risk estimates are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2. Results of critical appraisal are available online (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

Table 1. Study characteristics

AGECAT, Automatic Geriatric Examination for Computer-Assisted Taxonomy; CPRS, Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NACC, National Alzheimer′s Coordinating Center; NEO–PI–R, Revised NEO Personality Inventory; NPI–Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory – Questionnaire; PRIME-MD, Primary care evaluation of Mental Disorders; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

a. Risk estimates from fully adjusted models.

b. Subjective memory impairment.

c. Population drawn from retirement communities and other facilities.

Nine studies presented risk estimates regarding Alzheimer's disease. Sample sizes ranged from 185Reference Palmer, Berger, Monastero, Winblad, Bäckman and Fratiglioni29 to 12 083.Reference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24 The studies as a whole comprised 37 508 people. There was one case–control study.Reference Jessen, Wolfsgruber, Wiese, Bickel, Mosch and Kaduszkiewicz27 Mean follow-up time differed between threeReference Palmer, Berger, Monastero, Winblad, Bäckman and Fratiglioni29, Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32 and 11 years.Reference Bruijn, Direk, Mirza, Hofman, Koudstaal and Tiemeier25, Reference Terracciano, Sutin, An, O'Brien, Ferrucci and Zonderman31 As an exception, Zilkens et al Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 looked back up to 40 years. Two studies concentrated more or less on a middle-aged population,Reference Terracciano, Sutin, An, O'Brien, Ferrucci and Zonderman31, Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 whereas the remaining studies predominantly included older people, with two studies accepting participants aged >75 years only.Reference Jessen, Wolfsgruber, Wiese, Bickel, Mosch and Kaduszkiewicz27, Reference Palmer, Berger, Monastero, Winblad, Bäckman and Fratiglioni29

Two studies focused on trait anxiety assessed by the Revised NEO Personality Inventory.Reference Terracciano, Sutin, An, O'Brien, Ferrucci and Zonderman31, Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32 Unspecified anxiety symptoms were screened at baseline in five studies.Reference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24, Reference Bruijn, Direk, Mirza, Hofman, Koudstaal and Tiemeier25, Reference Lobo, Bueno-Notivol, de La Camara, Santabarbara, Marcos and Gracia-Garcia28–Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 Each study used a different instrument (Supplementary Table 2). Two studies checked evidence of anxiety disorders by psychiatric examination at baselineReference Bruijn, Direk, Mirza, Hofman, Koudstaal and Tiemeier25 or exploration of medical records.Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 Only Jessen et al Reference Jessen, Wolfsgruber, Wiese, Bickel, Mosch and Kaduszkiewicz27 analysed memory complaints and dementia worry in particular.

The prevalence of anxiety was reported in seven of nine studies. Prevalence varied between 2.15Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 and 44%.Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 The pooled prevalence of anxiety across seven studies was 9.4%. Depressive symptoms or depression were present in 9.3% of all participants. Six of nine studies assessed the role of depression as a confounding variable within regression analysis. Both anxiety and depression can be considered as independent risk factors. Coincidence of anxiety and depression is accompanied by a cumulative hazard ratio.Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30

Only one study showed overall critical risk of biasReference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24 (Supplementary Table 3). With regard to the only retrospective study, recall bias was avoided by studying files to detect presence of anxiety disorders.Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 Controls were randomly selected here.Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33

Three studies were based on epidemiological studies and therefore rated as being representative of the general population.Reference Bruijn, Direk, Mirza, Hofman, Koudstaal and Tiemeier25, Reference Lobo, Bueno-Notivol, de La Camara, Santabarbara, Marcos and Gracia-Garcia28, Reference Palmer, Berger, Monastero, Winblad, Bäckman and Fratiglioni29 Other studies included patients drawn consecutively or selected randomly from clinicsReference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24 and primary care,Reference Jessen, Wolfsgruber, Wiese, Bickel, Mosch and Kaduszkiewicz27, Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 volunteersReference Terracciano, Sutin, An, O'Brien, Ferrucci and Zonderman31 and seniors selected from retirement areas.Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32

The weight of evidence of included studies is presented in Supplementary Table 2. Quality was adequate to high in all cases, with three exceptions (Supplementary Table 4).Reference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24, Reference Lobo, Bueno-Notivol, de La Camara, Santabarbara, Marcos and Gracia-Garcia28, Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32 Five studies were rated less relevant methodologically because of the shortness of observation periodsReference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24, Reference Jessen, Wolfsgruber, Wiese, Bickel, Mosch and Kaduszkiewicz27, Reference Lobo, Bueno-Notivol, de La Camara, Santabarbara, Marcos and Gracia-Garcia28, Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30, Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32 and four studies were rated less relevant topically because of exploration of trait anxiety or dementia worry (Supplementary Table 5).Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26, Reference Jessen, Wolfsgruber, Wiese, Bickel, Mosch and Kaduszkiewicz27, Reference Terracciano, Sutin, An, O'Brien, Ferrucci and Zonderman31, Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32

Description of primary studies

Risk estimates from final regression models are cited from original work.

Both articles investigating trait anxietyReference Terracciano, Sutin, An, O'Brien, Ferrucci and Zonderman31, Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32 report positive associations with regard to Alzheimer's disease (hazard ratio 1.34, 95% CI 1.08–1.657; hazard ratio1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.09). There is no evidence for a systematic correlation between anxiety disorders and Alzheimer's disease. The odds ratio calculated by Zilkens et al Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 comprises different ICD diagnoses (odds ratio 1.08, 95% CI 0.81–1.45), whereas Bruijn et al Reference Bruijn, Direk, Mirza, Hofman, Koudstaal and Tiemeier25 provide risk estimates on each type of disorder separately. Neither the result of any of three subanalyses (generalised anxiety disorder, specific phobias, agoraphobia) nor the pooled risk ratio is positively correlated with development of dementia (hazard ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.58–1.45).

Anxiety is a predictive factor in four of six studies that observed individuals aged 65 years and over.Reference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24, Reference Jessen, Wolfsgruber, Wiese, Bickel, Mosch and Kaduszkiewicz27, Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30, Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32

Meta-analysis

The meta-analysis displays a positive association of anxiety as a predictor of Alzheimer's disease (n = 26 193 out of seven studies, hazard ratio1.53, 95% CI 1.16–2.01, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2). Two studies are not included because no hazard ratio was calculated.Reference Palmer, Berger, Monastero, Winblad, Bäckman and Fratiglioni29, Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33

Fig. 2 Forest plot for anxiety as a predictive factor for Alzheimer's disease. Legend: Squares and horizontal lines represent study effects and 95% CI, diamonds indicate the combined effect of each model. Vertical lines visualise overlap between study effects. The beam displays the prediction interval.

The sensitivity analysis was based on exclusion of the risk estimate reported by Burke et al Reference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24 because of highest risk of bias (Supplementary Fig. 1). Pooled hazard ratio was still significant (n = 14 110 out of six studies, hazard ratio1.35, 95% CI 1.08–1.70, P < 0.01). Some extent of publication bias is apparent when inspecting the corresponding funnel plots (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

Anxiety and risk of vascular dementia

Study characteristics and risk estimates are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2. Results of critical appraisal are available online (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

Study characteristics

Three studies investigated vascular dementia. One study analysed 1280 patients with vascular dementia and selected random controls retrospectively.Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 Stewart et al Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 evaluated data from 3082 people who had been recruited and examined consecutively by general practitioners. Gallacher et al Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26 analysed the development of 1160 males stemming from an epidemiologic study with 2358 participants at baseline. Individuals were followed up for 8 yearsReference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26 and up to 20 years,Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26 whereas Zilkens et al Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 drew on information up to 40 years ago. Both Zilkens et al Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 and Gallacher et al Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26 included individuals aged <65 years only, whereas participants of the third study were aged 68 years on average.Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30

Intensity of exposition was mixed across studies and assessed with Spielberger's State–Trait Anxiety Inventory with emphasis on trait anxiety,Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26 Primary care evaluation of Mental Disorders for detecting unspecified anxiety symptomsReference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 and ICD criteria for anxiety disorders.Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 Consequently prevalence rates were 50.4,Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26 44Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 and 2.15%.Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 Cardiovascular risk factors and depression were controlled in two analyses,Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26, Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 whereas Zilkens et al did not adjust for depression within the regression model. There is serious risk of bias across studies (Supplementary Table 3) because of unknown or high drop-out rates,Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26, Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 uncontrolled depressive symptomsReference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 and short-term follow-up.Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 Methodological quality as well as relevance is adequate to high (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

Description of primary studies

Risk estimates from final regression models are cited from original work.

One study reports no association between anxiety and vascular dementia (hazard ratio1.02, 95% CI 0.71–1.47).Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 Variables are positively correlated in the remaining two studies, but the results do not reach statistical significance (odds ratio 1.76, 95% CI 0.94–3.30Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 and odds ratio 2.79, 95% CI 0.6–13.06).Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26

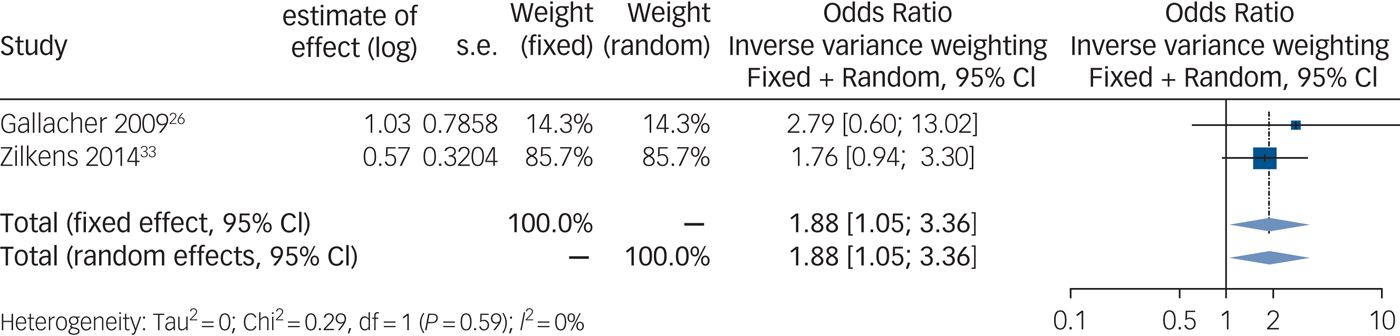

Meta-analysis

Synthesis of those studies, which calculated an odds ratio, shows a positive and significant association between anxiety and vascular dementia (Fig. 3) (n = 4916 out of two studies, odds ratio 1.88, 95% CI 1.05–3.36, P = 0.06).

Fig. 3 Forest plot for anxiety as a predictive factor for vascular dementia. Legend: Squares and horizontal lines represent study effects and 95% CI, diamonds indicate the combined effect of each model.

Discussion

This study presents a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the association between anxiety and Alzheimer's disease as well as vascular types. We performed a broad search initially including about 16 000 records. Ten studies could be included in this systematic review.

Quantitative analysis reveals a positive association between anxiety and both Alzheimer's disease (n = 26 193 out of seven studies; hazard ratio 1.53, 95% CI 1.18–2.01, P < 0.01) and vascular dementia (n = 4916 out of two studies; odds ratio 1.88, 95% CI, 1.05–3.36, P = 0.6). When looking at studies with lowest risk of bias, the association remains positive. Moreover age, gender, education and depression have been controlled in most studies and did not weaken the effect of anxiety on dementia significantly, whereas no study considered sleeping disorders, intake of benzodiazepines or drug misuse as confounding factors.

Size and direction of results are in line with recent findings of other meta-analyses exploring the association between anxiety-related psychiatric disorders,Reference Dondu, Sevincoka, Akyol and Tataroglu34–Reference Tapiainen, Hartikainen, Taipale, Tiihonen and Tolppanen36 psychosocial factorsReference Kuiper, Zuidersma, Oude Voshaar, Zuidema, van den Heuvel and Stolk37 and dementia. Pooled risk estimates of cited meta-analyses range from 1.6Reference Diniz, Butters, Albert, Dew and Reynolds35 to 3.1.Reference Terracciano, Sutin, An, O'Brien, Ferrucci and Zonderman31

Anxiety and Alzheimer's disease

Two studies endorsed the association between trait anxiety and Alzheimer's disease.Reference Terracciano, Sutin, An, O'Brien, Ferrucci and Zonderman31, Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32 Both results were not adjusted for depression, but findings were independent from gender. Personality traits are stable over time.Reference Steunenberg, Twisk, Beekman, Deeg and Kerkhof38 It is plausible that trait anxiety promotes permanent brain-damaging stress.Reference Beauquis, Vinuesa, Pomilio, Pavia, Galvan and Saravia39 Interestingly, personality traits are not correlated to neuropathogenic lesions,Reference Wilson, Begeny, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett32 suggesting that reduced cognitive reserve might be a crucial pathomechanism.Reference Marchant and Howard40, Reference Barulli and Stern41 Both results were not adjusted for depression, so this could have been a source of bias. Nevertheless it means that early treatment could possibly delay or avoid dementia.Reference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24 This needs further investigation. Bearing in mind that findings were independent from gender, the damaging pathway of anxiety and stress is likely to be independent from sex hormones. Moreover anxiety is not a sufficient explanation why Alzheimer's disease occurs more frequently in women.

Individuals displaying both anxious and depressive symptoms are at higher risk of Alzheimer's disease.Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 This is plausible according to the cumulative stress hypothesis.Reference McEwen42 Bearing that in mind, one would expect anxiety disorders to be at least as damaging as trait anxiety and depression because of their intensity and recurrence in many patients. Surprisingly, both studies exploring ICD or DSM diagnoses of anxiety did not find a significant relationship.Reference Bruijn, Direk, Mirza, Hofman, Koudstaal and Tiemeier25, Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 According to the stress hypothesis, trait anxiety might provoke chronic distress and allostatic load throughout life, whereas anxiety disorders differ in typical age at onset.Reference de Lijster, Dierckx, Utens, Verhulst, Zieldorff and Dieleman43 The probability of recovery ranges from 37% (social phobia) to 82% (panic disorder) within 12 years.Reference Bruce, Yonkers, Otto, Eisen, Weisberg and Pagano44 Thus, the effect of specific anxiety disorders on cognitive health might be different because of prognosis. In this systematic review, only one study provided information about subtypes, but no association with regard to Alzheimer's disease was found for generalised anxiety disorder, specific phobia and agoraphobia.Reference Bruijn, Direk, Mirza, Hofman, Koudstaal and Tiemeier25

Five of the seven pooled risk estimates stem from study populations with a mean age >65 years. Therefore, the result of the performed meta-analysis is influenced by age. The predictive value is probably due to reversed causality or reactive anxiety accompanied by subjective memory impairment in this age group. When considering Alzheimer's disease as a continuum, index age does not play a substantial role.Reference Whalley, Dick and McNeill45 Anxiety might play a role in the aetiology of, or at least have a catalytic effect on dementia.

Considering the cognitive reserve hypothesis, distinct emotions and behaviours could have a different effect on cognition. For example, anhedonia and withdrawal as core symptoms of depression could lead to adverse effects on brain health by inactivity and reduced stimulation, whereas affirmation of life and lifestyle might be less impaired in people with anxiety disorders.Reference Watson, Clark and Carey46 Melancholia but not comorbid anxiety in patients with depression was found to be a predictive factor with regard to future dementia.Reference do Couto, Lunet, Gino, Chester, Freitas and Maruta47

Anxiety and vascular dementia

Only two cohort studies and one case–control study explored the secondary objective. Two results were integrated in the quantitative synthesis.Reference Gallacher, Bayer, Fish, Pickering, Pedro and Dunstan26, Reference Zilkens, Bruce, Duke, Spilsbury and Semmens33 Depression but not anxiety was associated to future vascular dementia in the remaining study.Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 Given the minimum number of studies, this result has to be interpreted with caution. Vascular dementia is often accompanied by anxiety disorders.Reference Remes, Brayne, van der Linde and Lafortune48 Therefore the connection between anxiety and vascular dementia could be driven by comorbid cardiovascular disease and risk factors, depression, substance misuse and health-damaging behaviour in general. Anxiety might facilitate vascular damage and dementia via hypercoagulability, atherosclerosis and hypertension.Reference Esler49 Included studies controlled cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases to a large extent, strengthening the assumption that psychological distress is a shared feature within the course of both Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia and might lead to cognitive decline via adverse effects of cortisol.

Limitations

Although our search was designed to detect dementia and anxiety in the broadest sense, the search strategy did not include terms for depression and trauma. Thus, we might not have included studies that looked for dimensions of anxiety in depressive and traumatised patients. However, the populations with systemic and other mental diseases than anxiety disorders were excluded intentionally to a great extent to focus this systematic review on studies in which anxiety was the single independent variable to minimise confounding by specific underlying systemic conditions.

Although various databases with different areas of focus were chosen, our systematic review displays an inevitable evidence of publication bias in this particular field of research. One small studyReference Palmer, Berger, Monastero, Winblad, Bäckman and Fratiglioni29 could not be included in our quantitative analysis because no hazard ratio was provided. This study might have reduced the evidence of publication bias.

With regard to the meta-analysis, studies with incompatible risk estimates for both Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia were excluded. In light of the fact that the excluded studies yielded non-significant results, findings from quantitative analysis must be interpreted with caution. A remarkable amount of heterogeneity and several methodological limitations and inconsistencies across studies might weaken the validity of the positive association found in our meta-analysis. The diversity of different instruments for anxiety is broad, but non-validated tests were applied in only one study.Reference Jessen, Wolfsgruber, Wiese, Bickel, Mosch and Kaduszkiewicz27 Validated tests of the independent variable were not performed in an appropriate manner. For example, in one study the Neuropsychiatric Inventory was used in healthy participants.Reference Burke, O'Driscoll, Alcide and Li24 Another study arbitrary shortened the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating

Scale and segregated the anxiety items and depression items in a non–authorised manner.Reference Palmer, Berger, Monastero, Winblad, Bäckman and Fratiglioni29 Reporting was incomplete and reduced to a conference paper in two cases.Reference Lobo, Bueno-Notivol, de La Camara, Santabarbara, Marcos and Gracia-Garcia28, Reference Stewart, Perkins, Hendrie and Callahan30 Because of scarceness of long-term studies, we faced risk of reversed causality and recommend the design of fairly long-term studies in the future to avoid this problem.

Implications for the future

To our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to demonstrate a small association between anxiety and specific types of dementia in the sense of a predictive factor. Independently of age, anxiety is likely to damage the brain directly by permanent stress and indirectly by avoiding behaviour, inactive lifestyle and loss of cognitive reserve and resiliency. The preventive potential of treating anxiety and the role of lifestyle should be focused in future research. The question arises whether cognitive–behavioural therapy has the potential to end the vicious circle of worries and memory loss in the elderly population. Furthermore, trait anxiety should be taken seriously at an early age because it might be a modifiable risk factor of future dementia. The temporal or functional relation between anxiety and dementia needs more careful investigation in larger cohort studies with better biomarkers and psychometric measurement.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.173.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.