Compared with the general population, people with mental illness have a significantly reduced life expectancy. Reference Thornicroft1-4 Despite increased awareness of the importance of physical health in people with mental illness, this mortality gap appears to be widening. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely5,Reference Nielsen, Uggerby, Jensen and McGrath6 Research suggests that there is an increased prevalence of metabolic disease, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cancer and respiratory disease associated with mental illness, Reference De Hert, Correll, Bobes, Cetkovich-Bakmas, Cohen and Asai2,Reference De Hert, Cohen, Bobes, Cetkovich-Bakmas, Leucht and Ndetei3,Reference Stubbs, De Hert, Sepehry, Correll, Mitchell and Soundy7 and clearly this mandates rates of medical interventions and medical monitoring that are at least equal to those in the general population. Unfortunately, people with mental illness consistently receive suboptimal medical care. Reference Thornicroft1,Reference Mitchell, Malone and Doebbeling8-Reference Aggarwal, Pandurangi and Smith11 Recently a number of narrative reviews have established the existence of inequalities in the physical healthcare provision for people with mental illness who have cancer. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely5,Reference Aggarwal, Pandurangi and Smith11-Reference Baillargeon, Kuo, Lin, Raji, Singh and Goodwin13 This is concerning, since among the general population cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for about 8 million deaths in 2012. 14 Breast cancer is second only to lung cancer as the leading cause of cancer deaths for women. 15 In response to the increased mortality observed in women with breast cancer, at least 27 countries have nationwide screening for the condition. Reference Smith16 For instance, the US Preventive Services Task Force has recommended biennial mammography for women aged 50-74 years, 17 and in the UK women aged 50-70 years (extending to 47-73 years by the end of 2016) are invited to attend breast screening every 3 years as part of the National Health Service (NHS) breast screening programme. Reference Duffy, Tabar, Olsen, Vitak, Allgood and Chen18 An independent review by Cancer Research UK and the National Cancer Director investigated the benefits and risks of breast screening in October 2011 and concluded that the UK breast screening programme prevents 1300 cancer deaths per year, with approximately 16 000 women diagnosed each year but with about 4000 false positives. Reference Marmot, Altman, Cameron, Dewar, Thompson and Wilcox19 It is estimated that about 500 screening applications are needed to prevent one breast cancer death. 20 Within the general population meta-analyses have demonstrated that mortality from breast cancer is reduced by 15-20% among adults eligible to receive screening. Reference Hendrick, Smith, Rutledge and Smart21-Reference Magnus, Ping, Shen, Bourgeois and Magnus23 However, such screening is not without controversy. For instance, the recently updated Cochrane review stated that although screening reduces mortality by 15% there is a risk of overtreatment of approximately 30% among women in the general population. Reference Gotzsche and Jorgensen24

Women with a past or present diagnosis of a mental illness appear to be less likely to receive mammography compared with the general population. Reference Lord, Malone and Mitchell9,Reference Aggarwal, Pandurangi and Smith11 This is despite the fact that cancer mortality is substantially increased among this population, Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely5,Reference Osborn, Levy, Nazareth, Petersen, Islam and King25-Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence27 with those diagnosed with severe mental illness (SMI) at particular risk. This has led some authors to suggest that there is a need for targeted early detection and improved cancer screening among women with mental illness. Reference Musuuza, Sherman, Knudsen, Sweeney, Tyler and Koroukian26,Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence27 Although it is true that some studies, such as that by Ji et al, have found no increase or even a reduction in the prevalence of certain types of cancer in those with schizophrenia, Reference Ji, Sundquist, Ning, Kendler, Sundquist and Chen28 breast cancer risk appears to be consistently increased. Recently two systematic reviews reported a disparity in breast cancer screening among women with mental illness, Reference Lord, Malone and Mitchell9,Reference Aggarwal, Pandurangi and Smith11 but neither conducted a meta-analysis to quantify this relationship. Given the aforementioned concerns, there is a need to establish quantitatively if in fact women with mental illness are less likely to receive mammography screening. Thus, the aim of our systematic review and meta-analysis was to establish whether women with a past or present diagnosis of mental illness were less likely to receive mammography than members of the general population. Within this review we stratified the results to establish if a discrepancy existed in mammography screening due to a diagnosis of mental illness, mood disorders, depression, severe mental illness or distress and anxiety.

Method

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines and with reference to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement, Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie29,Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman30 utilising a predetermined but unregistered protocol.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible if they included women with a diagnosis of non-organic psychiatric disorder including SMI (e.g. schizophrenia, psychosis), mood disorders (depression, anxiety) according to recognised diagnostic criteria (DSM-IV or ICD-10), 31,32 or other valid measure. We also included studies that reported mammography screening among women with distress but no defined mental illness. Studies were also required to be comparative studies reporting mammography screening for women with and without a mental illness.

We did not aim to analyse studies that reported mammography screening in women with delirium, dementia, learning disability, eating disorder or alcohol use disorder. In fact we found no such study except those involving learning disability, which we excluded. Reference Sullivan, Glasson, Hussain, Petterson, Slack-Smith and Montgomery33 We did not place any language restriction upon eligible studies and if we encountered multiple publications from the same study, only the most recent paper or article with the largest sample with complete data was included. If we encountered studies that conducted mammography in a sample of women with and without a mental illness but did not report the data required for the meta-analysis, we contacted the authors up to three times to acquire the variables of interest.

Literature search and appraisal

Two authors (A.J.M., B.S.) independently conducted searches of Medline, PubMed and EMBASE electronic databases from inception until February 2014. We used the following keywords: mammogr* OR breast screen* OR breast cancer screen AND mental OR psychiatr* OR depression OR mood OR anxiety OR SMI OR schizophrenia OR psychosis OR psychotic. We also looked for similar studies using the symptom of distress rather than formal psychiatric disorder. The searches of major electronic databases were supplemented by full-text searches of Web of Knowledge, Scopus, Science Direct, Ingenta Select, Springer LINK and Wiley-Blackwell and hand-searching of all included articles. Finally, we conducted online hand searches of major psychiatric journals from 2000 up to February 2014, including the BMJ, British Journal of Psychiatry, Schizophrenia Research, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Psychological Medicine, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, American Journal of Psychiatry, Archives of General Psychiatry, Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, Journal of Psychiatric Research, Psychiatric Services and The Psychiatrist, and contacted numerous international experts to ensure completeness of data acquisition. Two authors independently completed the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) evaluation for all included articles (A.J.M., B.S.); the scale is a reliable and valid tool to assess the methodological quality of observational studies. Reference Wells, Shea, O'Connell and Peterson34

Data extraction

Data were extracted by four authors (I.P., M.Y., S.P., V.M.) and independently validated by another (A.J.M.) using a predetermined form. The data extracted included study design, setting, participant characteristics (number, mean age, gender, type of mental illness and classification criteria used), control participant characteristics, details of mammography screening measures and results, including statistical procedures used and factors adjusted for.

Statistical analysis

From the available data we calculated odds ratios (OR) together with the 95% confidence intervals and r values from each study. For the purposes of pooling data if we encountered relative risks (hazard ratios) among individual studies these were converted into odds ratios with reference to the reported control event rate, an adaption of a method described elsewhere. Reference Zhang and Yu35 We then used a random effects meta-analysis, pooling odds ratios comparing mammography screening in those with and without a mental illness. Wherever possible we attempted to account for potential confounders in the literature as reported within each study and stratified results into adjusted and unadjusted analyses. Confidence intervals were extracted from all studies or calculated from the data provided. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman36 Heterogeneity was further reduced by stratifying analyses by type of mental illness, but we required a minimum of three studies to justify separate pooling of results. Owing to the anticipated heterogeneity, all analysis was conducted with the DerSimonian & Laird random effects meta-analysis, Reference DerSimonian and Laird37 using Statsdirect for Windows (www.statsdirect.com). To assess publication bias Egger’s regression method and the Begg-Mazumdar test, with a P value below 0.05 suggesting the presence of bias, were used. Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder38,Reference Begg and Mazumdar39 In addition a funnel plot was generated for each analysis, in which the study-specific effect estimates were displayed in relation to the standard error in order to assess the potential presence of publication bias. Finally we calculated estimates of missed screens, based on the relative risk and prevalence of mental disorder, Reference Baumeister and Harter40,Reference Wittchen and Jacobi41 and the likely excess mortality by using the number of screening applications needed to prevent one death.

Results

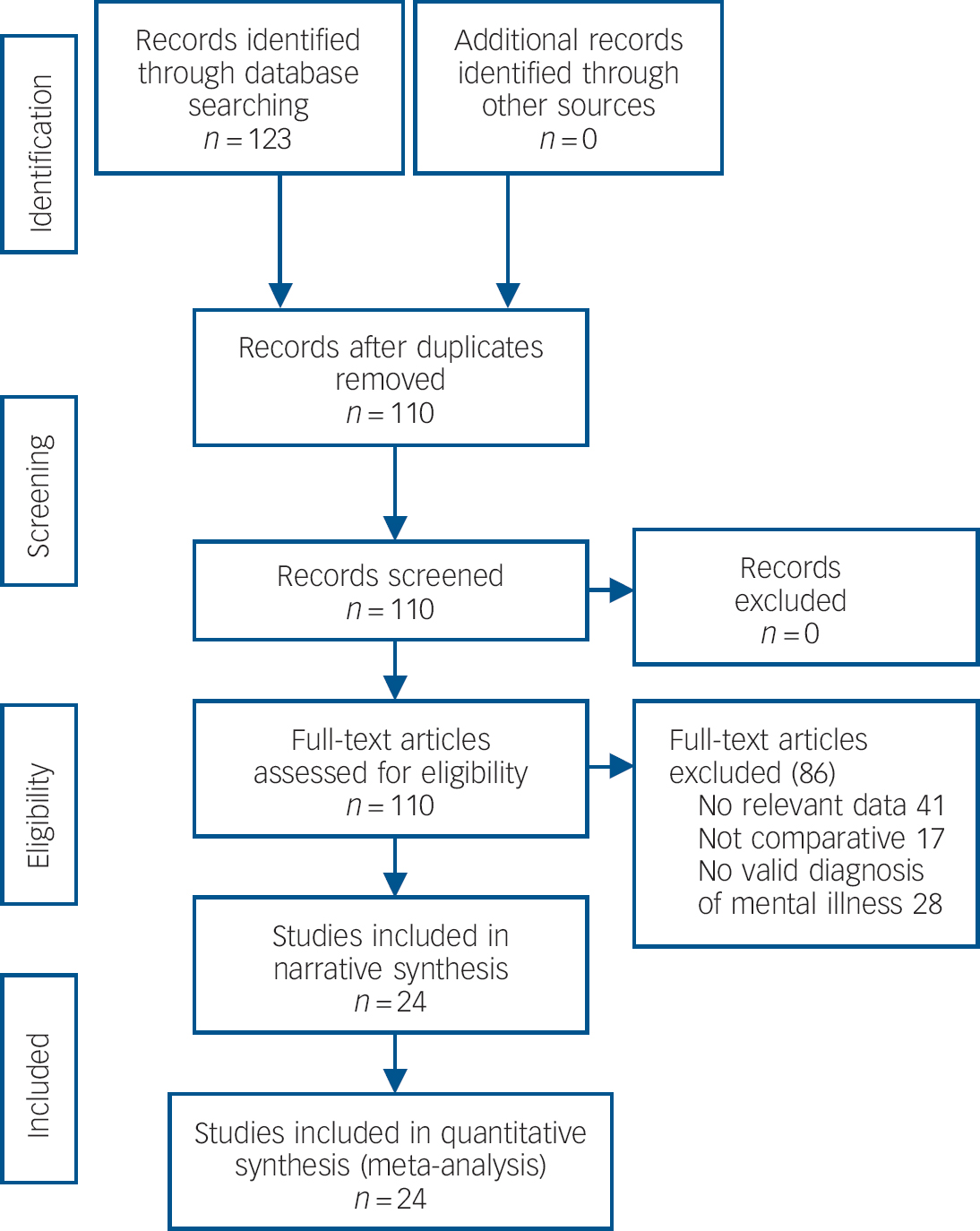

After the removal of duplicates the initial searches yielded 110 valid hits and following the application of the eligibility criteria, 24 publications were included. Reference Carney and Jones42-Reference Koroukian, Bakaki, Golchin, Tyler and Loue65 These consisted of 41 analyses involving 715 705 women with a diagnosis of mental illness and 5 analyses involving 21 491 women with broadly defined distress. At the full-text screening stage 86 articles were excluded (Fig. 1). Common reasons for exclusion were that the paper contained no relevant data, was not comparative or had no valid diagnosis of mental illness. The studies were all conducted in North America except for two. Reference Iezzoni, McCarthy, Davis, Harris-David and O'Day47,Reference Peytremann-Bridevaux, Voellinger and Santos-Eggimann51 Over half of the included studies (13 of 24) enquired about mammography screening over a 2-year period. Details of the included studies and participants are presented in online Table DS1. The NOS scores were good overall, with a mean score of 6.5 (s.d. = 0.9), and only one study was rated as poor quality. Reference Lindamer, Buse, Auslander, Unutzer, Bartels and Jeste45 The summary of the NOS score for each study is presented in online Table DS1.

Mammography screening rates

Mental illness

In total 41 separate analyses involving a combined 715 705 women were available to investigate the influence of any mental illness upon mammography screening (Fig. 2(a)). The random effects meta-analysis yielded a pooled OR of 0.71 (95% CI 0.66-0.77, P<0.0001), establishing that women with mental illness were significantly less likely to receive mammography screening compared with members of the general population. The I 2 statistic was high (95%) indicating high heterogeneity. The funnel plot was symmetrical (Fig. 2(b)) and neither the Begg-Mazumdar (Kendall’s ô = -0.0585, P = 0.58) nor the Egger bias (–1.37, P = 0.14) test demonstrated any evidence of publication bias.

Fig. 1 Study search procedure.

Mood disorders

Next we pooled the results from 22 analyses reporting mammography screening rates in individuals with mood disorder and controls (n = 399 153) (Fig. 3). The pooled OR was 0.83 (95% CI 0.76-0.90, P<0.0001), establishing a significant reduction in mammography screening rates among women with mood disorders. However, although the I 2 statistic for the analysis was high (90%), the funnel plot was symmetrical and the Begg-Mazumdar (Kendall’s ô = –0.012, P = 0.91) and Egger bias (–0.357, P = 0.69) tests did not demonstrate any evidence of publication bias. It was possible to pool the results of 17 analyses specifically investigating mammography screening rates in women with depression. This established an OR of 0.91 (95% CI 0.84-0.97, P = 0.01), indicating that women with depression are less likely to receive mammography screening compared with members of the general population. The I 2 was high (77%), but inspection of the funnel plot and the Begg-Mazumdar (Kendall’s ô = 0, P = 0.96) and Egger bias (0.765, P = 0.26) tests demonstrated there was no evidence of publication bias influencing the results.

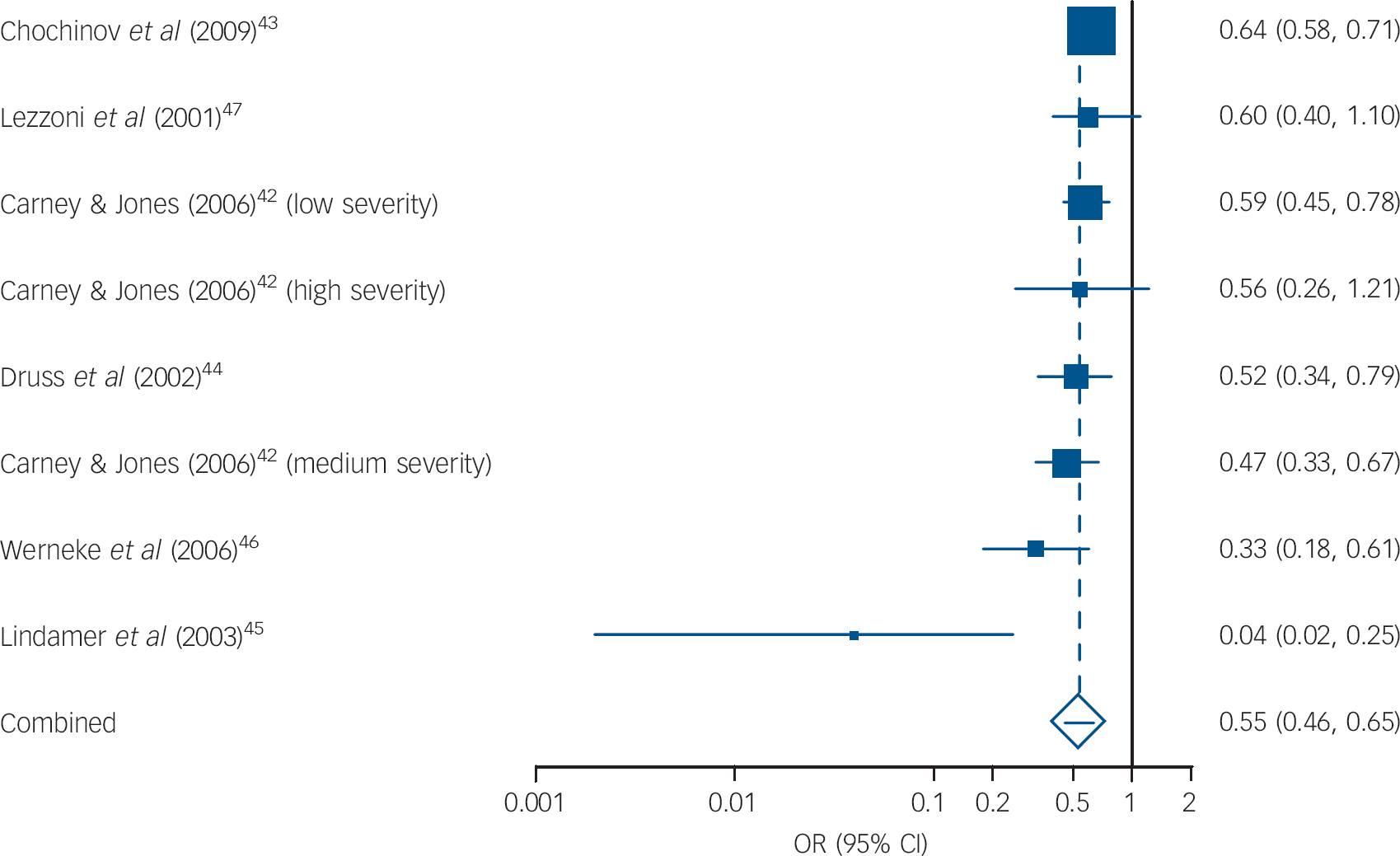

Serious mental illness

We pooled eight separate analyses regarding mammography screening in women with SMI compared with general population controls (n = 387 556) and found low heterogeneity (I 2 = 43%; Fig. 4). The pooled OR was 0.54 (95% CI 0.45-0.65) indicating that women with SMI are almost 50% less likely to receive mammography than members of the general population. The funnel plot was symmetrical and the Begg-Mazumdar test was satisfied (Kendall’s ô = –0.5, P = 0.06), but Egger’s test did indicate some evidence of publication bias (–1.529, P = 0.01).

Distress

In women with broadly defined distress but no formal diagnosis of mental illness we pooled five different analyses incorporating 21 491 women. Results did not suggest that women with distress were significantly less likely to receive mammography screening compared with general population controls (OR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.37-1.69, P = 0.54, I 2 = 88%). The Begg-Mazumdar and Egger bias tests for both analyses demonstrated no evidence of publication bias.

Missed screens

Finally, we calculated estimates of missed screens based on the relative risk and prevalence of mental disorder and the likely excess mortality by using the number of screens needed to prevent one death (online Table DS2). This established that 45 047 missed screening opportunities among women with mental illness might result in 90 deaths (95% CI 67-111) in the UK annually. Excess mortality estimates for women with mood disorder and SMI were calculated at 16 (95% CI 9-24) and 25 (95% CI 17-34) from 7857 and 12 571 missed screens respectively.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first meta-analysis investigating any general population medical screening according to diagnosis of mental illness and also the first regarding receipt of mammography. Results extend conclusions from previous narrative reviews showing disparities in medical care linked with mental illness. From qualifying mammography studies 715 705 unique individuals were included and results consistently showed that women with mental illness were likely to receive suboptimal breast cancer screening compared with those without a mental illness. Specifically, there was a significantly reduced level of receipt of mammography screening in women with any mental illness as well as in women with mood disorders. Indeed, a subgroup analysis showed that there was also a significant low receipt in those with depression. However, the largest effect was seen in women with SMI, who had almost 50% lower odds of receiving mammography when indicated. Given an estimated population uptake of 77.%, 66 and 1.94 million mammograms per year in England, this represents a relative risk (RR) of 0.91 in those with any mental illness, or approximately 45 000 missed screens, assuming a 27% prevalence of mental illness (online Table DS2). We also estimate an RR of 0.95 in mood disorders (or 7857 missed screens, assuming a 9% prevalence of mood disorder) and a RR of 0.84 in SMI (or approximately 12 571 missed screens; assuming a 4% prevalence of SMI). Given these figures, and the earlier calculation that about 500 screening applications may prevent one breast cancer death, then it is likely that this breast cancer screening inequality in women with mental ill health could result in 90 unnecessary deaths per year in the UK.

The results of our review might provide a partial explanation for the observation that cancer is detected later on average in people with mental illness, Reference O'Rourke, Diggs, Spight, Robinson, Elder and Andrus12,Reference Baillargeon, Kuo, Lin, Raji, Singh and Goodwin13,Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence27 and also help account for the fact that a greater proportion of cancer with metastases at presentation is found in psychiatric patients. Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence27 Coupled with the fact that people with a SMI such as schizophrenia are less likely to be offered timely treatment, Reference Baillargeon, Kuo, Lin, Raji, Singh and Goodwin13,Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence27 it is possible that reduced mammography screening rates could explain why cancer-related mortality is higher among women with mental illness. Reference Perini, Grigoletti, Hanife, Biggeri, Tansella and Amaddeo67 However, at this stage these links are speculative and further research is warranted to establish more clearly if increasing mammography screening uptake among people with mental illness would improve patient outcomes. The results of our study are nevertheless consistent with the overall physical healthcare disparity seen in women with mental illness. Reference Perini, Grigoletti, Hanife, Biggeri, Tansella and Amaddeo67 For instance, Osborn et al and Roberts et al found that those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were about half as likely as comparator groups to have had their blood pressure or smoking status recorded in primary care. Reference Osborn, Baio, Walters, Petersen, Limburg and Raine68,Reference Roberts, Roalfe, Wilson and Lester69 Indeed, a recent nationwide survey of medical monitoring across the UK found lower receipt of medical testing in those with SMI compared with people with diabetes. Reference Mitchell and Hardy70 Differences were still apparent once non-attendance was adjusted for. We have previously demonstrated that people with mental illness receive lower rates of medical care, lower rates of appropriate drug treatment and lower rates of medical procedures. Reference Mitchell, Malone and Doebbeling8,Reference Lord, Malone and Mitchell9,Reference Mitchell, Lord and Malone71 Here we extend these findings to highlight a disparity in mass medical population-based screening for breast cancer.

Fig. 2 Mammography screening in women with mental illness. (a) Pooled odds ratios: random effects meta-analysis. (b) Bias assessment plot.

Fig. 3 Mammography screening in women with mood disorders. Pooled odds ratios: random effects meta-analysis.

Possible reasons for low screening rates

One plausible hypothesis is that the low uptake in those with mental illness is explained by current distress. Stress, distress and anxiety have been linked to short-term risk-averse behaviours resulting in avoidance of screening invitations. Reference Ng and Jeffery72 Indeed, distress has been linked with low uptake of mass screening such as mammography and colorectal cancer screening. Reference O'Donnell, Goldstein, DiMatteo, Fox, John and Obrzut73,Reference Kotwal, Schumm, Mohile and Dale74 However, there may also be a bimodal, inverted U-shaped relationship between screening and anxiety, with both high concern and high distress linked with lower screening rates. Reference Consedine, Morgenstern, Kudadjie-Gyamfi, Magai and Neugut75 In this study in a large sample of 21 491 women we found no significant link between distress and mammography. Unfortunately there were insufficient data to analyse the effect of anxiety alone, but when anxiety and distress were pooled we still were unable to demonstrate any consistent link. This suggests that current distress (or anxiety) is probably not the explanation for low receipt of mammography.

Another possible reason for the low screening rates among women with mental illness is low rates of presentation for medical help, largely a patient-determined factor (help-seeking). For instance, Hardy & Gray found that only 66% of those with SMI attended an appointment in primary care when specifically invited for a physical health check, compared with 81% of those with diabetes in the same centre. Reference Hardy and Gray76 However, other studies have found that attendance is not the main variable in determining medical care inequalities. Reference Mitchell, Malone and Doebbeling8,Reference Lord, Malone and Mitchell9,Reference Mitchell and Hardy70 Kahn et al stipulated that patient education is key to facilitating breast cancer screening among women with mental illness. Reference Kahn, Fox, Krause-Kelly, Berdine and Cadzow77 For example, patients commonly fear pain or discomfort when attending for mammography, and education and reassurance might ameliorate these concerns and improve attendance. Reference Kahn, Fox, Krause-Kelly, Berdine and Cadzow77 If the low receipt of screening is explained by low help-seeking rates then more attention is needed during the invitation process aimed at those with known psychiatric diagnoses and other low-attendance groups. A follow-up telephone call can improve attendance in those with mental illness. Reference Mitchell and Selmes78 A second explanation might be the influence of cognitive impairment on decision-making. Most people with mental illness do not have substantial enduring cognitive impairment, but several past studies have found that low uptake occurs in those with learning disabilities. Reference Sullivan, Glasson, Hussain, Petterson, Slack-Smith and Montgomery33,Reference Legg, Clement and White79 This requires further study.

Fig. 4 Mammography screening in women with severe mental illness. Pooled odds ratios: random effects meta-analysis.

Not all mammography occurs as a result of routine screening invitations. Indeed, in many low-income countries mammography is by clinician request. However, in such countries most clinicians do not send asymptomatic women for screening, unless the patient makes a specific request. Reference Temitope, Daniel and Ademola80 Hence a number of authors have stipulated the importance of good communication between primary care providers and mental health services to maximise cancer screening among women with mental illness. Reference Kahn, Fox, Krause-Kelly, Berdine and Cadzow77,Reference Miller, Lasser and Becker81,Reference Friedman, Puryear, Moore and Green82 Research in the general population has also stipulated the importance of having a primary care provider to improve screening rates, Reference Starfield, Leiyu and Macinko83 but it may be that trust and social support are additionally important to facilitate screening attendance in women with mental illness. Reference Aggarwal, Pandurangi and Smith11 The importance of good communication and continuity of care has previously been emphasised in a qualitative study involving people with SMI and healthcare professionals. Reference Lester, Soroham and Tritter84 However, the low screening rates may be partly ascribed to a failure of primary healthcare providers to take the physical healthcare complaints of people with mental illness seriously. 4 For instance, healthcare providers may fail to screen people with mental illness for cancer owing to a preoccupation with other comorbidities and confusion around symptom attributes. Reference Aggarwal, Pandurangi and Smith11 One author stated that providers attributed many of the patients’ physical complaints to their psychiatric symptoms, which resulted in an underestimation of the post-test probability of other medical conditions. Reference Masterson, Hopenhayn and Christian54

Study limitations

It is important that a number of limitations are considered when considering the results of this review. First, most of the analyses that we conducted had considerable heterogeneity. We attempted to negate this and improve clinical relevance by stratifying the results according to clinical diagnosis and also by reporting only random effects meta-analysis. Second, most studies were conducted in North America, and may not be generalisable to other areas of the world with different healthcare systems. Third, it may be that shared risk factors such as social deprivation may account for the low mammography uptake, but it was not possible to investigate this clearly within the analysis. Fourth, the time frame over which mammograms were recorded varied across studies. Lastly, there was heterogeneity in the classification of mental illness, with a range of classification criteria used, and some authors used retrospective history. However, despite these factors, the results from our large meta-analysis were consistent: people with mental illness, particularly those with serious disorders, are substantially less likely to receive mammography screening compared with members of the general population.

Clinical implications

People with mental illness are at significant risk of not attending breast cancer screening although reasons for this disparity remain to be confirmed. Most research shows that people with mental illness receive inferior medical care. Reference Thornicroft1,Reference Mitchell, Malone and Doebbeling8 Cancer is particularly burdensome in people with mental illness, and clearly such people should receive care that is at least comparable with care given to the general population. Although there has been some debate in the general medical literature regarding the use of mammography (see, for example, Jorgensen & Kotzsche), Reference Jorgensen and Gotzsche85 the inequality demonstrated within this review is clearly not proportionate to this group’s healthcare needs. This is particularly so when research has demonstrated that among people with mental illness cancer is often detected later, and when it is detected more metastases are often found. Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence27 However, care is needed when employing large-scale mammography screening because false positives may cause psychological harm. Reference Jorgensen and Gotzsche85 A recent longitudinal study found that in the general population annual mammography screening had no effect on breast cancer mortality beyond that of physical breast examinations. Reference Miller, Wall, Baines, Sun, To and Narod86 However, it remains unclear if this finding applies to those with mental illness. Indeed, people with severe mental illness may not receive regular physical health checks and are probably less likely to carry out self-examination. In order to enhance breast cancer screening, it is important that there is better communication between NHS England’s screening services, primary care providers and mental health services. Reference Kahn, Fox, Krause-Kelly, Berdine and Cadzow77,Reference Miller, Lasser and Becker81,Reference Friedman, Puryear, Moore and Green82 Efforts should also be made to educate and support women with mental illness to engage in breast cancer screening and social support may be particularly important in achieving this. Reference Aggarwal, Pandurangi and Smith11

Future research

Future prospective research should investigate the barriers to as well as the facilitators of mammography screening among women with mental illness. This should use both qualitative and quantitative research methods, drawing upon the experiences of the patients and of mental healthcare and primary care providers. Additionally, it is essential that prospective longitudinal studies are conducted to investigate the influence of mammography screening upon the diagnosis (including false positives), treatment and ultimately the mortality of women with mental illness.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Verity Markham for additional help with an earlier draft of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.