Bipolar disorder and major depression are common affective disorders, affecting approximately 2% Reference Merikangas, Akiskal, Angst, Greenberg, Hirschfeld and Petukhova1 and 16% Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas and Walters2 of the population respectively. In addition to significant psychiatric morbidity, they also have an adverse impact on social and occupational functioning, quality of life and physical health, Reference Martin and Smith3–Reference Stommel, Given and Given8 and often coexist with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Reference Glassman and Shapiro9 The association of both major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder with cardiometabolic risk factors, vascular disease and poor cardiovascular outcomes is well recognised. Reference Ormel, Von Korff, Burger, Scott, Demyttenaere and Huang10–Reference Herbst, Pietrzak, Wagner, White and Petry12

Although psychotropic medications alter cardiovascular risk profiles (through weight gain, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and glucose dysregulation), their use is also associated with a range of demographic and lifestyle factors, including social deprivation, smoking and alcohol use. Reference Britvic, Maric, Doknic, Pekic, Andric and Jasovic-Gasic13 To date, there has been no large-scale population-based study in the UK that has assessed associations between a lifetime history of depressive or bipolar features and adverse cardiometabolic outcomes while also taking account of a wide range of potential confounding factors, including psychotropic medications.

Beyond the UK, there have been a number of large-scale reports assessing the association between mood disorders and cardiometabolic disease, including the National Comorbidity Study Replication Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas and Walters2 and the World Mental Health Survey. Reference Moussavi, Chatterji, Verdes, Tandon, Patel and Ustun7 Although very informative, these studies did not assess the wide range of covariates we have been able to include in our analyses. The landmark UK Biobank cohort, Reference Collins14 comprising over half a million adults in middle age, represents a unique opportunity to explore these associations at a population level (both cross-sectionally and prospectively) and has the potential to inform future mechanistic studies and the development of population-level interventions. Here we assess relationships between five cardiometabolic diseases (myocardial infarction, angina, hypertension, diabetes and stroke) and lifetime features of affective disorders (major depression and bipolar disorder) within UK Biobank. In additional subanalyses we also assess the effect of psychotropic medication on cardiometabolic disease.

Method

Data source

UK Biobank is a large prospective cohort of more than 502 000 residents of the UK, aged between 40 and 70 years. Reference Smith, Nicholl, Cullen, Martin, Ul-Haq and Evans15 It is one of the largest resources worldwide for studying the genetic, environmental, medication and lifestyle factors that cause or prevent disease in middle and older age. Recruitment was undertaken over a 4-year period, from 2006 to 2010. In the final 2 years of UK Biobank recruitment, 172 751 participants were assessed in detail with respect to lifetime features of bipolar disorder and major depression. Eligibility for inclusion in our study was restricted to the 145 991 participants who provided complete data on lifetime features of mood disorder and complete data on self-reported cardiometabolic disease status. Reference Smith, Nicholl, Cullen, Martin, Ul-Haq and Evans15

Data collection and ethical approval

Participants attended one of 22 assessment centres located across Great Britain. They completed a touchscreen questionnaire that collected information on demographics (including age, gender, ethnicity and postcode), health-related behaviours (including smoking status and alcohol consumption) and a self-report of physician-diagnosed medical conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, angina and stroke. Current medication was recorded with assistance from a member of trained clinic staff, who also used standard operating procedures to measure height and weight for body mass index (BMI) calculation. This study was conducted under generic approval from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (approval letter dated 17 June 2011, Ref 11/NW/0382) and full written informed consent was gained from participants at the point of data collection.

Definitions

Criteria for a lifetime history of clinically significant features of bipolar disorder or depression were based on responses to questions within the baseline touchscreen questionnaire (see online supplements DS1 and DS2). Although not diagnostic of bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder, these questions were similar to questions assessing mood disorders within structured diagnostic assessment instruments. To some extent the validity of these questions has been supported internally within this data-set by comparisons of gender distribution, socioeconomic status, self-reported health rating, current depressive symptoms and smoking status. Reference Smith, Nicholl, Cullen, Martin, Ul-Haq and Evans15

For the purposes of this study, participants were categorised into three groups: those with bipolar disorder features, those with features of major depression and a control group (Appendix). Reference Smith, Nicholl, Cullen, Martin, Ul-Haq and Evans15,Reference Langan, Mercer and Smith16 ‘Any cardiovascular disease’ was defined as the self-report of a previous physician diagnosis of hypertension, myocardial infarction, angina and/or stroke. Diabetes was also defined by self-report. BMI was determined though anthropometric measurements carried out at the assessment centre and categorised into underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), class I obese (30.0–34.9 kg/m2), class II obese (35.0–39.9 kg/m2) and class III obese (⩾40 kg/m2). Reference Ul-Haq, Mackay, Martin, Smith, Gill and Nicholl17 Smoking status, frequency of alcohol consumption and ethnic group were self-reported on the touchscreen questionnaire. Smoking status was classified as ‘current smoker’, ‘previous smoker’ or ‘never smoked’ and alcohol use was classified as ‘daily/almost daily’, ‘3–4 times per week’, ‘1–2 times per week’, ‘1–3 times/month’, ‘special occasions only’ or ‘never’. Ethnicity was categorised as: ‘White’, ‘mixed’, ‘Asian/Asian British’, ‘Black/Black British’, ‘Chinese’, and ‘other’. The Townsend deprivation index – an area-based measure of socioeconomic status derived from information collected in the census on car ownership, over-crowding, owner-occupation and unemployment – includes both positive and negative values, with positive values indicating higher levels of deprivation. Reference Ul-Haq, Mackay, Martin, Smith, Gill and Nicholl17 Townsend scores were divided into quintiles (within the study population) to facilitate comparisons. The use of current medication (including psychotropics) was self-reported by participants and a comprehensive list of commonly used psychotropics was identified (online supplement DS3). Participants were classified as using psychotropic medication if they reported currently taking any of these medications.

Statistical analyses

Differences in baseline characteristics between the three groups (control, depressive features and bipolar features) were analysed using the chi-squared test for categorical data and the chi-squared test for trend for ordinal data. We used separate logistic regression models to examine the associations between mood group and cardiometabolic disease categories (‘any cardiovascular disease’ (not including diabetes), diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, angina or stroke), with controls as the referent group. These primary outcomes were used to provide a more comprehensive analysis of common cardiometabolic comorbidities in the depressive and bipolar features groups. Models were initially adjusted for age, gender, socioeconomic deprivation and ethnicity (a partially adjusted model) and then repeated including additional covariates: smoking status, frequency of alcohol use, BMI and the use of psychotropic medication (fully adjusted model). Interaction tests for gender were undertaken and subgroup analyses carried out as appropriate.

To explore the relative contribution of psychotropic medication to cardiometabolic risk across the mood spectrum, we carried out a subanalysis to assess the effect of current psychotropic medication and mood group status on cardiometabolic disease across the mood spectrum. Six groups were created: individuals with no mood disorder features and not currently taking psychotropic medication (our referent group); individuals with no mood disorder features but currently taking one or more psychotropic medications; individuals with depressive features not currently taking psychotropic medication; individuals with depressive features currently taking one or more psychotropic medications; individuals with features of bipolar disorder not currently taking any psychotropic medication; and individuals with features of bipolar disorder currently taking psychotropic medication.

Differences in cardiometabolic outcomes between different mood and medication status groups were reported as prevalences and then analysed using the chi-squared test for categorical data. We again used separate logistic regression models to examine associations between medication and mood disorder group with cardiometabolic disease (diabetes, myocardial infarction, angina, hypertension or stroke). As noted above, controls who were not currently taking psychotropic medication were chosen as the most appropriate referent group. These models were adjusted for age, gender, socioeconomic deprivation and ethnicity, smoking, alcohol and BMI. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1. Statistical significance was defined conservatively as P<0.001.

Results

Group characteristics: bipolar features, depression features and controls

A total of 172 751 UK Biobank participants were assessed at baseline with respect to lifetime history of depressive and bipolar features. Of these, complete data on mood disorder features and cardiometabolic disease status were available for 145 991 (84.5%). From this sample, according to our criteria in the Appendix, 1557 (1.07%) had features of bipolar disorder, 30 990 (21.23%) had features of major depression and 113 444 (77.71%) had no significant features of mood disorder (controls) (Table 1).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics (n = 145 991)

| n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | Depression features group | Bipolar features group | P a | |

| Participants | 113 444 (77.7) | 30 990 (21.2) | 1557 (1.1) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 57 082 (50.3) | 20 004 (64.5) | 766 (49.2) | <0.001 |

| Male | 56 362 (49.7) | 10 986 (35.5) | 791 (50.8) | |

| Age, years | ||||

| 39–49 | 25 215 (22.2) | 8027 (25.9) | 492 (31.6) | <0.001 |

| 50–60 | 40 012 (35.3) | 12 351 (39.9) | 624 (40.1) | |

| 61–72 | 48 217 (42.5) | 10 612 (34.2) | 441 (28.3) | |

| Body mass index category | ||||

| Underweight | 552 (0.5) | 159 (0.5) | 15 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Normal weight | 37 613 (33.2) | 9783 (31.6) | 451 (29.0) | |

| Overweight | 48 835 (43.1) | 12 578 (40.6) | 614 (39.4) | |

| Class I obese | 19 473 (17.2) | 5708 (18.4) | 328 (21.1) | |

| Class II obese | 5186 (4.6) | 1888 (6.1) | 108 (6.9) | |

| Class III obese | 1785 (1.6) | 874 (2.8) | 41 (2.6) | |

| Townsend score quintile | ||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 19 541 (17.1) | 4802 (15.5) | 169 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 23 102 (20.4) | 5781 (18.7) | 205 (13.2) | |

| 3 | 23 659 (20.9) | 6270 (20.2) | 260 (16.7) | |

| 4 | 25 414 (22.4) | 7197 (23.2) | 384 (24.7) | |

| 5 (most deprived) | 21 728 (19.2) | 6940 (22.4) | 539 (34.6) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 103 786 (91.5) | 29 295 (94.5) | 1385 (89.0) | <0.001 |

| Mixed | 777 (0.7) | 264 (0.9) | 25 (1.6) | |

| Asian/Asian British | 3811 (3.4) | 564 (1.8) | 65 (4.2) | |

| Black/Black British | 3248 (2.9) | 522 (1.7) | 50 (3.2) | |

| Chinese | 471 (0.4) | 49 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) | |

| Other | 1351 (1.2) | 296 (1.0) | 26 (1.7) | |

a. Chi-squared test.

Participants with features of depression were younger and more likely to be women (Table 1). Current smoking was most common in the bipolar features group (21.3%), followed by the depressive features group (12.7%) and then the non-mood-disordered control group (8.8%) (Table 2). The proportions of different levels of socioeconomic deprivation were mixed between the groups, but of note was that 34.6% of the bipolar features group were in the most deprived quintile, compared with 22.4% for the depressive features group, and 19.2% for the control group. White ethnicity was most common in the depressive features group and least common in the bipolar features group (Table 1).

Table 2 Lifestyle and clinical characteristics (n = 145 991)

| n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 113 444) |

Depression features group (n = 30 990) |

Bipolar features group (n = 1 557) |

P a | |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Daily/almost daily | 23 377 (21.0) | 6134 (19.8) | 318 (20.4) | <0.001 |

| 3–4 times/week | 26 571 (23.4) | 6588 (21.2) | 263 (16.9) | |

| 1–2 times/week | 29 107 (25.7) | 7467 (24.1) | 337 (21.6) | |

| 1–3 times/month | 12 317 (10.9) | 3943 (12.7) | 196 (12.6) | |

| Special occasions only | 12 737 (11.2) | 4091 (13.2) | 231 (14.8) | |

| Never | 8935 (7.9) | 2767 (8.9) | 212 (13.6) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 65 154 (57.4) | 15 647 (50.5) | 667 (42.8) | <0.001 |

| Previous | 38 320 (33.8) | 11 412 (36.8) | 559 (35.9) | |

| Current | 9970 (8.8) | 3931 (12.7) | 331 (21.3) | |

| Psychotropic medication | ||||

| No | 109 577 (96.6) | 24 603 (79.4) | 1057 (67.9) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 3867 (3.4) | 6387 (20.6) | 500 (32.1) | |

| Cardiovascular disease any | ||||

| No | 80 854 (71.3) | 21 516 (69.4) | 1020 (65.5) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 32 590 (28.7) | 9474 (30.6) | 537 (34.5) | |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 107 457 (94.7) | 29 260 (94.4) | 1449 (93.1) | 0.002 |

| Yes | 5987 (5.3) | 1730 (5.6) | 108 (6.9) | |

| Hypertension | ||||

| No | 83 762 (73.8) | 22 316 (72.0) | 1073 (68.9) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 29 682 (26.2) | 8674 (28.0) | 484 (31.1) | |

| Myocardial infarction | ||||

| No | 111 046 (97.9) | 30 314 (97.8) | 1502 (96.5) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 2398 (2.1) | 676 (2.2) | 55 (3.5) | |

| Angina | ||||

| No | 110 296 (97.2) | 29 979 (96.7) | 1494 (96.0) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 3148 (2.8) | 1011 (3.3) | 63 (4.0) | |

| Stroke | ||||

| No | 111 974 (98.7) | 30 428 (98.2) | 1523 (97.8) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1470 (1.3) | 562 (1.8) | 34 (2.2) | |

a. Chi-squared tests.

Patterns of alcohol use were similar between groups (Table 2) and obesity was more common in both the depressive features and bipolar features groups compared with the control group (Table 1). Rates of current psychotropic medication use were highest in the groups with bipolar (32.1%) and depressive (20.6%) features and lowest within the control group (3.4%) (Table 2).

Prevalence of cardiometabolic disease

The prevalence of ‘any cardiovascular disease’ was highest in the bipolar features group (34.5%), followed by the depressive features group (30.6%) and lowest in the control group (28.7%). Similar patterns were observed for hypertension, myocardial infarction, angina and stroke (Table 2). Cardiometabolic disease frequencies were also calculated for men and women. Men had consistently higher rates of all cardiometabolic diseases and, in general, rates of cardiometabolic disease were highest in the bipolar features group, followed by the depressive features group and the control group (Table 2).

Partially adjusted model

On multivariate logistic regression (adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic deprivation and ethnicity), odds ratios (ORs) for all cardiometabolic outcomes were significantly increased in the depressive features and the bipolar features groups relative to controls (all P<0.001, Table 3, see also online Table DS1 for a more detailed version of this table that includes an analysis by gender). In general, the odds of each cardiometabolic outcome, as well as the odds of having ‘any cardiovascular illness’, increased across the two mood groups, in the depressive features group and the bipolar features group (Table 3). It should be noted, however, that findings for the bipolar features group with respect to diabetes and stroke were not statistically significant. The highest odds ratios in the partially adjusted model for the combined male and female group were for myocardial infarction (OR = 1.90, 95% CI 1.44–2.51) and angina (OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.30–2.19) within the bipolar features group relative to controls, and for diabetes (OR = 1.29, 95% CI 1.22–1.37) in the depressive features group relative to controls (Table 3).

Table 3 Logistic regression analysis of cardiometabolic disease associated with mood disorder a

| Partially adjusted b | Fully adjusted c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Cardiovascular disease any | ||||

| Control | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| Depression | 1.29 (1.25–1.33) | <0.001 | 1.15 (1.12–1.19) | <0.001 |

| Bipolar | 1.50 (1.34–1.68) | <0.001 | 1.28 (1.14–1.43) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Control | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| Depression | 1.29 (1.22–1.37) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.03–1.13) | 0.038 |

| Bipolar | 1.37 (1.15–1.67) | 0.002 | 1.01 (0.81–1.24) | 0.960 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Control | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| Depression | 1.27 (1.23–1.31) | <0.001 | 1.15 (1.13–1.18) | <0.001 |

| Bipolar | 1.44 (1.29–1.61) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.12–1.42) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | ||||

| Control | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| Depression | 1.38 (1.26–1.51) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.08–1.30) | <0.001 |

| Bipolar | 1.90 (1.44–2.51) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.09–1.92) | 0.011 |

| Angina | ||||

| Control | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| Depression | 1.49 (1.39–1.61) | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.14–1.33) | <0.001 |

| Bipolar | 1.69 (1.30–2.19) | <0.001 | 1.21 (0.93–1.58) | 0.154 |

| Stroke | ||||

| Control | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| Depression | 1.61 (1.46–1.78) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.13–1.40) | <0.001 |

| Bipolar | 1.80 (1.27–2.54) | 0.001 | 1.17 (0.82–1.67) | 0.373 |

a. See online Table DS1 for a more detailed version of this table that includes data for men and women separately.

b. Partially adjusted for age, gender, deprivation and ethnicity.

c. Fully adjusted for age, gender, deprivation, ethnicity, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption and psychotropic medication.

There was a significant interaction between mood disorder and gender in predicting risk of having ‘any cardiovascular illness’ (P<0.001) and subgroup analyses by gender were subsequently carried out (Table DS1). Men with bipolar features had elevated odds ratios for myocardial infarction (2.02, 95% CI 1.50–2.72). The odds ratio for myocardial infarction in women was not significantly elevated in the partially adjusted group (1.37, 95% CI 0.65–2.92). Women with bipolar features had slightly higher odds ratios for any cardiovascular disease (1.55, 95% CI 1.32–1.83 in women v. 1.46, 95% CI 1.25–1.69 in men) and for hypertension (1.46, 95% CI 1.24–1.73 in women v. 1.42, 95% CI 1.22–1.66 in men) (Table DS1).

The odds ratios for specific conditions within the depressive features group were broadly similar for men and women. For angina this was OR = 1.54 (95% CI 1.40–1.69) for men and OR = 1.43 (95% CI 1.27–1.61) for women. Similarly, for diabetes the OR for men was 1.32 (95% CI 1.23–1.44) and for women the OR was 1.25 (95% CI 1.15–1.36). In women with depressive features, the odds ratio for stroke was 1.70 (95% CI 1.47–1.97) compared with 1.53 (95% CI 1.33–1.76) for men (Table DS1).

Fully adjusted model

On additional adjustment for smoking status, frequency of alcohol consumption, BMI and the use of psychotropic medication, the risk of having ‘any cardiovascular illness’ remained significantly elevated in both the depressive (OR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.12–1.19) and the bipolar features groups (OR = 1.28, 95% CI 1.14–1.43) (Table 3). This pattern was also largely present in a subgroup analysis by gender (Table DS1). In the fully adjusted model, odds ratios for hypertension and myocardial infarction were also significantly elevated in the combined male and female groups (hypertension: depression features group OR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.13–1.18, bipolar features group OR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.12–1.42; myocardial infarction: depression features group OR = 1.18, 95% CI 1.08–1.30) (Table 3).

Differences in odds ratios for angina and stroke within the fully adjusted, combined group analyses were not statistically significant. There were, however, elevations in odds of cardiovascular conditions within the depressive features group, most notably for stroke (OR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.13–1.40) (Table 3). Associations with diabetes were not significant in the fully adjusted model in either the depressive features or bipolar features groups. Odds ratios were reduced by approximately a quarter for many of the outcome measures on the additional adjustment for BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption and psychotropic medication.

Current use of any psychotropic medication

We carried out a subanalysis to assess the contribution of current psychotropic medication use to cardiometabolic risk in the control group, the depressive features group and the bipolar features group. In total, 109 557 individuals without features of mood disorder who were not taking psychotropic medication were identified as a control group (Table 4). There were 3867 individuals who did not meet the criteria for depressive or bipolar features but who reported taking one or more psychotropic medications (Table 4). Although the indication for these medications was not known, individuals who did not meet the criteria for depressive or bipolar disorder but reported taking one or more psychotropics displayed higher prevalences of all cardiometabolic diseases compared with controls. Of particular note were elevated rates of diabetes (8.97%), angina (5.87%), hypertension (36.07%) and stroke (3.98%) (Table 4).

Table 4 Cardiometabolic disease in mood and medication groups

| n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood group | Total, n | Diabetes | Myocardial infarction |

Angina | Hypertension | Stroke |

| Controls not on psychotropic medication | 109 577 | 5640 (5.15) | 2262 (2.06) | 2921 (2.67) | 28 287 (25.81) | 1316 (1.20) |

| Controls on psychotropic medication | 3867 | 347 (8.97) | 136 (3.52) | 227 (5.87) | 1395 (36.07) | 154 (3.98) |

| Depressive features not on psychotropic medication | 24 603 | 1199 (4.87) | 508 (2.06) | 690 (2.80) | 6609 (26.86) | 370 (1.50) |

| Depressive features on psychotropic medication | 6387 | 531 (8.31) | 168 (2.63) | 321 (5.03) | 2065 (32.33) | 192 (3.01) |

| Bipolar features not on psychotropic medication | 1057 | 108 (10.22) | 55 (5.20) | 63 (5.96) | 484 (45.79) | 34 (3.22) |

| Bipolar features on psychotropic medication | 500 | 48 (9.60) | 25 (5.00) | 24 (4.80) | 165 (33.00) | 16 (3.20) |

As illustrated in Table 4, compared with controls not on psychotropic medication, individuals with depressive features plus no psychotropic medication had similar rates of diabetes, myocardial infarction, angina, hypertension and stroke. Participants with depressive features taking psychotropic medication had higher rates of all cardiometabolic diseases compared with controls not on psychotropic medication. Individuals with bipolar features not taking psychotropic medication had higher rates of cardiometabolic disease relative to controls not on psychotropic medication. As expected, cardiometabolic diseases were also more prevalent for individuals with bipolar features who reported taking psychotropic medication.

Fully adjusted medication analyses

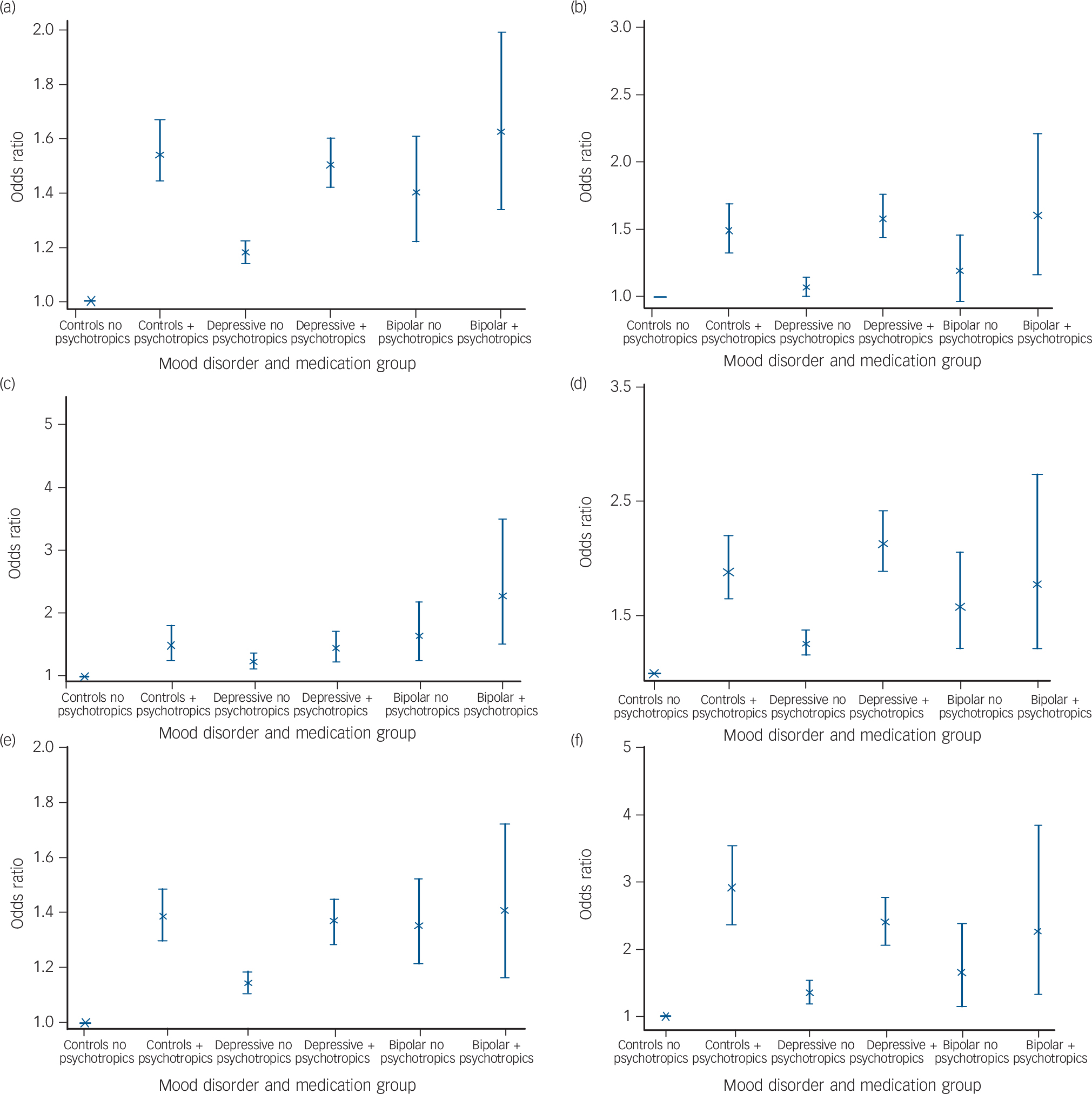

To assess the relative contribution of current psychotropic medication use in cardiometabolic disease across the mood spectrum we carried out a multivariate logistic regression adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic deprivation, ethnicity, smoking status, frequency of alcohol consumption and BMI (Fig. 1(a)–(f)). In general, odds ratios for most cardiometabolic diseases remained significantly elevated in each of the mood and medication groups relative to controls (Fig. 1(a)–(f)). Exceptions were for diabetes in the depressive features group not taking psychotropic medication, the bipolar features group not taking psychotropic medication, and the bipolar group currently taking psychotropic medication. Increases in odds ratios in the bipolar features group not on psychotropic medication group were also not significantly elevated for angina (OR = 1.58, 95% CI 1.22–2.06) and stroke (OR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.20–2.41).

Fig. 1 Logistic regression analysis of (a) any cardiovascular disease, (b) diabetes, (c) myocardial infarction, (d) angina, (e) hypertension and (f) stroke associated with mood disorder and medication status.

Results adjusted for age, gender, socioeconomic deprivation, ethnicity, smoking status, frequency of alcohol consumption and body mass index.

Furthermore, odds ratios for angina and stroke were not significantly elevated for both the bipolar features groups (those currently not taking psychotropic medication, as well as those taking psychotropic medication) (Fig. 1(d) and (f)). In general, however, the odds of reporting a history of an adverse cardiometabolic outcome were associated with both psychotropic medication use and with mood disorder (Fig. 1(a)–(f)) and the size of these associations increased with mood disorder severity (from depression to bipolar).

Discussion

We found that in a very large population sample of adults with lifetime features of depression and bipolar disorder there was an increased risk of comorbid cardiovascular disorders, even after adjusting for a wide range of confounding factors. In general, these associations were more pronounced for individuals with features of bipolar disorder than features of depression. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we also identified an association between current use of psychotropic medication and risk of cardiometabolic disease in individuals with a history of depressive and bipolar features. It is, however, notable that this association also occurred in individuals with no definite history of mood disorder who were currently taking psychotropic medication.

Both the bipolar features and depressive features groups had significantly higher odds ratios for ‘any cardiovascular disease’ relative to controls, within partially and fully adjusted models. Given the broad range of common confounding variables that were adjusted for, this suggests an independent association between mood disorder and cardiometabolic diseases. Within the partially adjusted (for age, gender, deprivation, ethnicity) versus fully adjusted models (additionally adjusted for BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption and psychotropic medication), odds ratios for ‘any cardiovascular disease’ fell from 1.29 (partial) to 1.15 (full) within the depressive features group and from 1.50 (partial) to 1.28 (full) in the bipolar features group. Although depression has been considered a risk factor for cardiovascular disease for some time, Reference Elderon and Whooley18 there has been debate about the relative contribution of lifestyle factors for this group of patients. We have been able to control for some of these lifestyle factors.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the general population design, the breadth of coverage of confounding factors and the very large sample size. However, several limitations are acknowledged. Cardiometabolic disorders previously diagnosed by a physician were self-reported by the participants. Similarly, mood disorder features were self-reported, rather than assessed using a formal diagnostic interview, although a structured approach was used (Appendix). Psychiatric diagnoses based on formal interviews were not practical within UK Biobank, so we took a pragmatic approach to mood disorder groupings. It is possible that our criteria for mood disorder are less stringent than formal diagnostic criteria. It should be noted, however, that we are reporting features of mood disorders at a population level, rather than formal clinical diagnoses, and we were unable to validate diagnoses because of the lack of availability of definitive diagnostic information. Similarly, because of a lack of definitive cardiometabolic diagnostic information we were unable to validate outcome measures. This lack of validation for both cardiometabolic and psychiatric diagnoses has implications in terms of the likely sensitivity and specificity of our groupings, which are based on self-report. Linkage to routine hospital and general practice health records will be available in the future and will allow some validation of these groups.

There is, however, evidence for the validity of these groupings using internal variables, Reference Nordentoft, Wahlbeck, Hallgren, Westman, Osby and Alinaghizadeh19 for example, the gender distributions of approximately 1:1 for bipolar disorder and approximately 2:1 (women:men) for depression are consistent with a large body of epidemiological research on lifetime rates of mood disorder in men and women. Reference Kessler, McGonagle, Swartz, Blazer and Nelson20,Reference Hwu, Joyce, Karam, Lee, Lellouch and Wickramaratne21 Furthermore, the lifetime prevalence rates for bipolar disorder (1.1%) and recurrent major depressive disorder (21.2%) are consistent with other population-based lifetime estimates. Reference Smith, Nicholl, Cullen, Martin, Ul-Haq and Evans15

Although we are reasonably confident that members of the control groups did not have significant features of depression or bipolar disorder, it should be noted that a proportion may have fulfilled criteria for other mental illnesses, such as anxiety disorder or, less likely, schizophrenia, both of which have been associated with poor cardiometabolic health. Reference Nordentoft, Wahlbeck, Hallgren, Westman, Osby and Alinaghizadeh19,Reference De Hert, Correll, Bobes, Cetkovich-Bakmas, Cohen and Asai22,Reference Lahti, Tiihonen, Wildgust, Beary, Hodgson and Kajantie23 There are also limitations with our broad definition of current psychotropic medication use that groups together different classes of medication. In a subanalysis of individuals on psychotropic monotherapy, we found that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), other antidepressants and sedatives/hypnotics were all associated with greater risk of myocardial infarction relative to psychotropic-free controls (SSRIs OR = 1.82, 95% CI 1.51–2.21; other antidepressants OR = 1.50, 95% CI 1.20–1.87; and sedatives/hypnotics OR = 2.53, 95% CI 1.76–3.66). It is therefore possible that adverse cardiovascular outcomes in depressive disorders are not limited to the use of antipsychotics but may also be a consequence of other classes of psychotropic medications.

A relatively low proportion of the mood disorder features groups reported taking psychotropic medication (bipolar features 32.1%, depressive features 20.6% and controls 3.4%) but, as noted above, the focus in this study was not clinically diagnosed mood disordered groups but rather lifetime features of mood disorder at a population level. Poor adherence with medication may be an issue. According to some estimates, up to 50% of patients prescribed psychotropic medication do not take their medication regularly. Reference Trivedi, Lin and Katon24–Reference Gadkari and McHorney26 Although adherence for physical health medications may be slightly better than this, Reference Cramer and Rosenheck27 it is likely that the factors that cause poor adherence with psychotropic medication may also lead to poor adherence with cardiovascular medications in individuals with mood disorders. This might explain the proportionately worse cardiovascular outcomes in a less adherent mood disordered group compared with a more adherent non-mood disordered group. As a result of the level of information on medication status that was collected at baseline, we were unable to assess the impact of duration of exposure to psychotropic medication on adverse cardiometabolic outcomes.

We included a range of possible confounding variables in the regression models but were unable to control for physical activity. The available data on physical activity were not collected in terms of standardised measures. Unfortunately, it was not possible to create a standardised measure, such as the metabolic equivalent of task (MET). Similarly, we were unable to adjust for the potential confounding effects of diet. When considering appropriate variables to include as confounding variables, it is important to note that there is uncertainty as to the extent that these variables might represent confounders or mediators. For example, obesity may represent an important component of the pathophysiology for depression, bipolar disorder and coronary heart disease. A prospective cohort study is required to address these concerns and is planned as part of future work in this cohort.

Our analyses did not assess the additive effects of sociodemographic and lifestyle factors. Rather, given the large number of confounding factors involved, we took a broad approach, focusing on cardiovascular outcomes after partial and full adjustment for confounders.

Severity of mood disorder may have contributed to the associations we observed. We therefore conducted an additional analysis of the impact of illness severity on cardiovascular disease outcomes. The depressive features group were divided into those who had a history of a probable single episode of major depression, versus those with a history of probable moderate recurrent depression and those with probable severe recurrent depression (Appendix). The bipolar group was also split into those with features of probable bipolar type I illness and those with features of probable bipolar type II illness (Appendix). In general, individuals in the more severe mood disorder groups had higher risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. For the bipolar type I group the odds ratio of ‘any cardiovascular illness’ was 1.39 (95% CI 1.23–1.58), for the recurrent severe depression group the OR was 1.33 (95% CI 1.18–1.50) and for the bipolar type II group the OR was 1.21 (95% CI 1.09–1.32).

Findings in the context of previous work

Many studies have identified an association between major depression and cardiovascular disease but relatively few studies have examined this with respect to bipolar disorder. Reference Hare, Toukhsati, Johansson and Jaarsma28 Although some reports in the literature support the association between bipolar disorder and cardiovascular disease, Reference Ösby, Brandt, Correia, Ekbom and Sparén4,Reference Ramsey, Leoutsakos, Mayer, Eaton and Lee29–Reference Weiner, Warren and Fiedorowicz31 these studies have not been able to adjust for the same range of confounding factors as our study.

Relative to controls, women with features of bipolar disorder had a greater risk of ‘any cardiovascular disease’ than men with bipolar features (OR 1.36 v. 1.19). This finding may be particularly noteworthy given that men are known to have increased rates of cardiovascular disease within the general population. In their 2013 population study, Crump and colleagues Reference Crump, Sundquist, Winkleby and Sundquist30 reported increased all-cause mortality for women with bipolar disorder compared with men with bipolar disorder (adjusted hazard ratio of 2.13 compared with 1.74). Furthermore, the same study reported higher hazard ratios of death from ischaemic heart disease for women with bipolar disorder compared with men with bipolar disorder (2.14 compared with 1.73). Our findings add to the evidence that women with bipolar disorder may be disproportionately affected by cardiovascular disease. Reference Fiedorowicz, He and Merikangas11

In our fully adjusted model for individuals with depressive or bipolar features, men (but not women) had an increased risk of myocardial infarction, and women (but not men) were at higher risk of stroke (Table DS1). There are several possible explanations for this, including studies that have found that men are more likely to receive a diagnosis of myocardial infarction than women Reference Shah, Griffiths, Lee, McAllister, Hunter and Ferry32 and that stroke is more commonly diagnosed in middle-aged women than in men. Reference Towfighi, Saver, Engelhardt and Ovbiagele33 We also found that, compared with both controls and women, men with depressive features had a higher risk of ‘any cardiovascular disease’ and hypertension, supporting previous findings in this area. Reference Fiedorowicz, He and Merikangas11 Furthermore, we found that in the combined male and female results, depressive features were associated with an increased risk of ‘any cardiovascular disease’. Although odds ratios were not as large as previous studies Reference Herbst, Pietrzak, Wagner, White and Petry12 this may underscore the importance of adjusting for a wide variety of confounding factors where possible.

Possible mechanisms

There are several possible underlying mechanisms for the associations we have observed, including shared behavioural factors, inequalities in treatment, shared genetic vulnerabilities and shared pathophysiology. Individuals with mood disorder may have difficulties in accessing preventative medical interventions, as well as higher rates of risky lifestyle factors. Reference Carney and Freedland34 Such factors include smoking, physical inactivity and reduced adherence with cardiovascular medications. Reference Freedland, Carney and Skala35,Reference Whooley, de Jonge, Vittinghoff, Otte, Moos and Carney36 In keeping with other work, smoking was more common in the bipolar features group than the depressive features and control groups. Reference Heffner, Strawn, DelBello, Strakowski and Anthenelli37 Given the negative impact of smoking on cardiovascular health, Reference Ezzati, Henley, Thun and Lopez38 this is clearly relevant to our findings of increased cardiovascular risk in both the bipolar and depressive features groups. Our results also show a significant attenuation in odds ratios when moving from partially adjusted to fully adjusted analyses, underlining the impact of smoking, alcohol, medication and BMI on cardiovascular risk in individuals with depressive and bipolar features.

Although our study adds to knowledge on the possible contribution of lifestyle and demographic factors to the association between cardiometabolic disease and mood disorder, it cannot contribute substantially to understanding pathophysiological mechanisms. Several biological systems may contribute to the comorbidity between mood disorder and cardiometabolic disease, including (but not limited to) abnormalities of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, Reference Rosmond and Björntorp39–Reference Watson, Gallagher, Del-Estal, Hearn, Ferrier and Young42 oxidative stress processes, Reference Khanzode, Dakhale, Khanzode, Saoji and Palasodkar43 shared genetic vulnerability, Reference Kendler, Gardner, Fiske and Gatz44–Reference Torkamani, Topol and Schork47 abnormal inflammatory responses, Reference Hansson48,Reference Joynt, Whellan and O'Connor49 endothelial dysfunction Reference Rybakowski, Wykretowicz, Heymann-Szlachcinska and Wysocki50,Reference Steinberg, Chaker, Leaming, Johnson, Brechtel and Baron51 and haemodynamic reactivity. Reference Strike and Steptoe52

We did, however, find that the use of psychotropic medication was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in all groups, even those without features of mood disorder. The metabolic effects of psychotropic medications are known to increase cardiometabolic risk by various mechanisms, including weight gain Reference Allison, Newcomer, Dunn, Blumenthal, Fabricatore and Daumit53 and impaired glucose tolerance. Reference Sernyak, Leslie, Alarcon, Losonczy and Rosenheck54 Given that our analyses were conducted on the basis of current use of any psychotropic medication, it is perhaps noteworthy that adverse cardiometabolic effects may not be limited to antipsychotics. There are reports in the literature of other psychotropic medications used in the treatment of mood disorder, such as antidepressants, lithium and valproic acid, having adverse metabolic effects. Reference Baptista, Teneud, Contreras, Alastre, Burguera and de Burguera55–Reference Fava, Judge, Hoog, Nilsson and Koke57

Future work

There remain several unanswered questions and opportunities for further research. There is a need for longitudinal and mechanistic studies in this area to better understand causal pathways. Reference Faith, Matz and Jorge58 To date, very few studies have tested specific genetic associations between lifestyle-related risk factors for cardiometabolic disease across the broad clinical spectrum of mood disorders. In addition, further mechanistic studies examining epigenetic factors, as well as oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and HPA axis abnormalities will be important to better understand comorbidity between mood disorder and cardiometabolic disease.

Appendix

Criteria for lifetime features of bipolar disorder and depression

Bipolar disorder features

-

(a) Features of bipolar disorder, type I: ever ‘manic or hyper’ for at least 2 days OR ever ‘irritable/argumentative’ for 2 days; plus at least 3 features from ‘more active’, ‘more talkative’, ‘needed less sleep’ and ‘more creative/more ideas’; plus duration of a week or more; plus ‘needed treatment or caused problems at work’.

-

(b) Features of bipolar disorder, type II: ever ‘manic or hyper’ for at least 2 days OR ever ‘irritable/argumentative’ for 2 days; plus at least 3 features from ‘more active’, ‘more talkative’, ‘needed less sleep’ and ‘more creative/more ideas’; plus duration of a week or more.

Major depression features

-

(a) Features of single-episode major depression: ever depressed/down for a whole week; plus at least 2 weeks duration; plus only one episode; plus ever seen a general practitioner (GP) or a psychiatrist for ‘nerves, anxiety, depression’ OR ever anhedonic (unenthusiasm/uninterest) for a whole week; plus at least 2 weeks duration; plus only one episode; plus ever seen a GP or a psychiatrist for ‘nerves, anxiety, depression’.

-

(b) Features of recurrent major depression (moderate): ever depressed/down for a whole week; plus at least 2 weeks duration; plus at least two episodes; plus ever seen a GP (but not a psychiatrist) for ‘nerves, anxiety, depression’ OR ever anhedonic (unenthusiasm/uninterest) for a whole week; plus at least 2 weeks duration; plus at least two episodes; plus ever seen a GP (but not a psychiatrist) for ‘nerves, anxiety, depression’.

-

(c) Features of recurrent major depression (severe): ever depressed/down for a whole week; plus at least 2 weeks duration; plus at least 2 episodes; plus ever seen a psychiatrist for ‘nerves, anxiety, depression’ OR ever anhedonic (unenthusiasm/uninterest) for a whole week; plus at least 2 weeks duration; plus at least two episodes; plus ever seen a psychiatrist for ‘nerves, anxiety, depression’.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.