Major depressive disorder (MDD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) are two common sequelae of early life maltreatment (ELM).Reference Zanarini, Williams, Lewis, Reich, Vera and Marino1–Reference Scott, McLaughlin, Smith and Ellis3 Intergenerational effects may emerge as mothers with a history of ELM, as well as MDD and BPD, show an increased risk for becoming abusive parents themselves.Reference Hiraoka, Crouch, Reo, Wagner, Milner and Skowronski4–Reference Shay and Knutson6 Hiraoka et al.Reference Hiraoka, Crouch, Reo, Wagner, Milner and Skowronski4 found that the association of BPD features and child abuse potential in parents was partially mediated by difficulties in emotion regulation. Although this study was able to give an important insight into the mechanisms of transmission, it did not focus on the effects of the often co-occurring history of ELM with child abuse potential. This issue has not yet been investigated for MDD, although emotion regulation problems also play a significant role in this type of disorder.Reference Joormann and Stanton7 In terms of ELM, the findings by Smith et al.Reference Smith, Cross, Winkler, Jovanovic and Bradley5 similarly suggest a mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties for elevated child abuse potential, but they did not consider co-occurring psychiatric disorders. The mediating effect of emotion regulation difficulties in the association of ELM and abuse potential may play a prominent role in mothers with BPD or MDD, and the link between ELM and emotion regulation may not persist when these disorders are taken into account. Finally, although extensive research has demonstrated the negative effects of child abuse on child well-beingReference Jaffee8, there has not been much attention given to the question of whether child abuse potential is linked to child mental health.Reference Haskett, Scott and Fann9

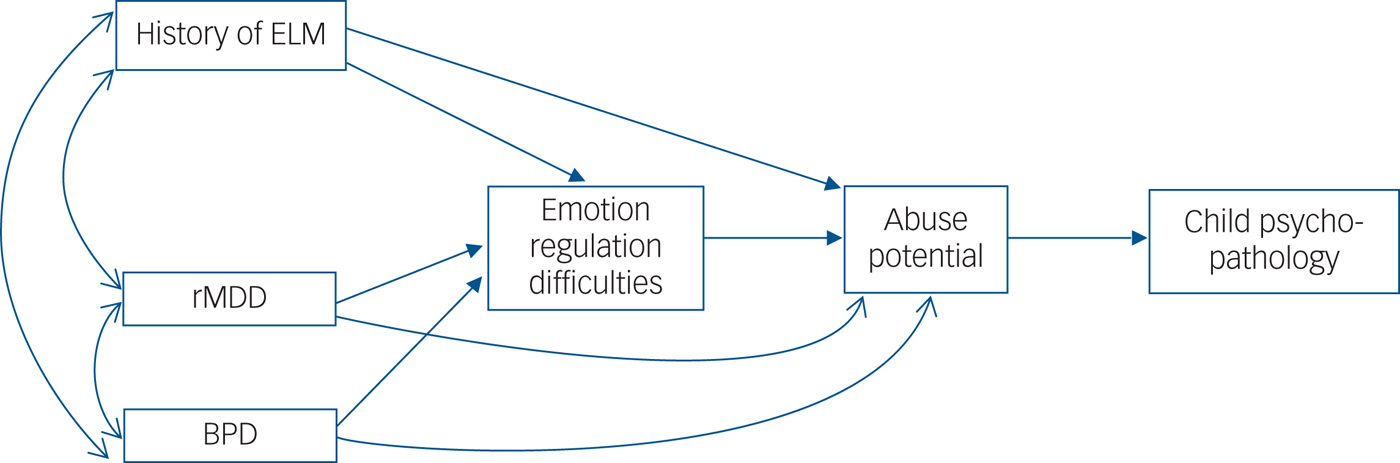

As MDD and BPD have high comorbidity,Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Dubo, Sickel, Trikha and Levin10 and both disorders are common reactions to ELM,Reference Zanarini, Williams, Lewis, Reich, Vera and Marino1, Reference Nelson, Klumparendt, Doebler and Ehring2 we sought to include all three risk factors in one study. We aimed at disentangling their individual contributions to child abuse potential and investigating the mediating role of maternal emotion regulation to promote the understanding of these factors in the intergenerational transmission of abuse and psychopathology. Further, we wanted to determine whether maternal child abuse potential is associated with child psychopathology. Understanding these processes of transmission may provide the starting point for the development of long-term interventions to break the cycle of intergenerational transmission and promote child well-being. All three maternal risk factors (ELM, BPD and MDD) were considered in this study to be exogenous (predictor) variables in a one-path analytic model, emotion regulation may be a mediator between these risk factors and abuse potential, and child psychopathology was chosen as the endogenous (outcome) variable linked with abuse potential (Fig. 1). We hypothesised that (a) maternal MDD, BPD and severity of ELM are associated with higher levels of abuse potential, (b) the effects of BPD and MDD on abuse potential are mediated by emotion regulation difficulties, and (c) there is a positive association between abuse potential and child psychopathology.

Fig. 1 Path model for direct and indirect associations of maternal early life maltreatment (ELM), major depressive disorder in remission (rMDD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) with maternal difficulties in emotion regulation, maternal child abuse potential and child psychopathology. Bidirectional arrows indicate covariance between two variables and one-directional arrows indicate a directional relationship. Covariation between ELM, BPD and rMDD was an intended result of our recruitment strategy which aimed at including considerable numbers of mothers with either zero, one, two or three risk factors. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Method

Participants and procedure

This study was performed within the framework of the Understanding and Breaking the Intergenerational Cycle of Abuse (www.ubica.de) multicentre project that investigates the effects of maternal history of abuse on mother–child interaction and child well-being.Reference Kluczniok, Boedeker, Fuchs, Hindi Attar, Fydrich and Fuehrer11 This study included 114 mothers and their children aged between 5 and 12 years old (see Table 1). BPD was diagnosed in 19 mothers and MDD in remission (rMDD) was diagnosed in 71 mothers. A total of 64 mothers experienced ELM with at least moderate severity before the age of 17. There was an intended co-occurrence of two or all three risk factors in parts of our sample which consisted of mothers with/without ELM and/or rMDD and/or BPD (see Table 1 for detailed information). A total of 13.1% of mothers did not show any of these risk factors (i.e., no rMDD, no BPD and not even mild forms of ELM). Note that prevalence rates of and correlations (co-occurrence) between our predictor variables are due to our recruitment strategy (we specifically and intentionally recruited mothers with ELM, BPD and/or rMDD) and thus they do not allow conclusions on the general population.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics

ELM, early life maltreatment; rMDD, major depressive disorder in remission; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; BPD, borderline personality disorder; TRF, Teacher Report Form.

History of ELM was defined as having experienced at least one type of abuse or neglect according to the main scales (sexual, physical and emotional abuse, neglect and parental antipathy) of the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Interview (CECA).Reference Bifulco, Brown and Harris12 For our analyses we used a dimensional sum score of all CECA scales. The frequencies of the types of ELM experienced with at least moderate severity are shown in Table 1.

Mother–child dyads were recruited by advertising (flyer or poster) in psychiatric, psychotherapeutic, gynaecological and paediatric out-patient clinics, as well as educational counselling and youth welfare offices. The advertisement indicated that we were searching for healthy mothers as well as mothers with a history of ELM, rMDD and BPD.

Mothers with BPD had to be non-suicidal and stable enough (i.e., not staying in hospital) to participate in the study. Mothers with MDD had to be in the remitted state. In this way we excluded the effects of acute depression, which may override the effects of BPD and ELM. In addition, acute symptoms of MDD may interfere with participation in the study and cause bias in response behaviour. Thus rMDD, with depressive symptoms on a subclinical level, was chosen as a more adequate comparison group than acute MDD, and only mothers with a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)Reference Hamilton13 score of below or equal to seven were included. The exclusion criteria for mothers included conditions that could potentially impair their ability to participate in the study: neurological diseases, lifetime history of schizophrenia, manic episodes, an acute depressive episode and anxious-avoidant or antisocial personality disorder as assessed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller14 and the International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE).Reference Loranger, Janca and Sartorius15 Intake of benzodiazepines within the past 6 months was a further exclusion criterion because consumption and withdrawal of these substances may have a particularly strong impact on the response behaviour in the measures used. However, medication consisting of other psychotropic drugs did not represent an exclusion criterion as long as dosages had been stable for at least 2 weeks prior to entering the study. The exclusion criteria of the child participants included previous diagnosis of autistic disorder and intellectual disability. Mothers and children had to live together because the aim of our project was to investigate the effect of maternal factors on child behaviour. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants after the procedure had been fully explained.

Measures

Emotion regulation difficulties

We assessed maternal difficulties in emotion regulation with the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS),Reference Gratz and Roemer16 which is a brief self-report questionnaire. High psychometric properties could be demonstrated for the German version.Reference Rusch, Westermann and Lincoln17 We entered the total (dimensional) score of the instrument in our analysis.

Abuse potential

We administered the Eltern-Belastungs-Screening zur Kindeswohlgefährdung (EBSK),Reference Deegener, Spangler, Körner and Becker18 the German version of the Child Abuse Potential Inventory (CAPI).Reference Milner19 The EBSK (CAPI) is a self-report questionnaire that screens for the risk of child abuse by assessing multiple adverse factors associated with child abuse and neglect. The CAPI was originally developed to assess the risk for physical abuse. However, studiesReference Deegener, Spangler, Körner and Becker18 also demonstrated significantly higher scores in families with other forms of abuse and neglect. Good internal consistency was reported for the German version of this test.Reference Deegener, Spangler, Körner and Becker18 The CAPI contains validity indices (random responding and faking), which did not indicate any bias in this study of these instruments.

Maternal psychopathology

To assess maternal history of depression (and other diagnoses of DSM-IV (1994) axis I disorders), we implemented the MINI,Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller14 which is a fully structured diagnostic interview for screening DSM-IV axis I disorders. Previous research has shown good inter-rater reliability.Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Janavs, Weiller and Keskiner20 We administered the IPDE,Reference Loranger, Janca and Sartorius15 which is a structured clinical interview with an established reliability and validity, to assess BPD according to ICD-10 (1992).Reference Loranger, Janca and Sartorius15, Reference Mombour, Zaudig, Berger, Gutierrez, Berner and Berger21 Interviews were conducted by clinical psychologists (holding bachelor's or master's degrees) after they had been trained by experienced users of these instruments.

Early life maltreatment (ELM)

We conducted the German versionReference Kaess, Parzer, Mattern, Resch, Bifulco and Brunner22 of the CECAReference Bifulco, Brown and Harris12 to assess maternal experiences of ELM. The CECA uses investigator-based ratings to collect retrospective accounts of adverse childhood experiences (up to an age of 17 years) – such as sexual, physical and emotional abuse, neglect and parental antipathy – in a semi-structured clinical interview. The data were rated according to predetermined criteria and manualised threshold examples using a four-point scale of severity (‘severe,’ ‘moderate,’ ‘mild’ or ‘little/none’). Interviews were administered by psychologists (holding bachelor's or master's degrees) who had been trained (3-day training) and approved by the author of the interview, Antonia Bifulco. Originally, lower scores on the four-point scales indicate higher maltreatment severity. We recoded these scores, with higher scores indicating higher severity, to ease interpretation. The sum score of all five CECA dimensions was entered into analysis.

Child psychopathology

Child psychopathology was assessed using the German version24 of the Teacher Report Form (TRF),Reference Achenbach23 which measures teacher-reported emotional and behavioural problems in children. Previous studies reported that the German version has good psychometric characteristics.Reference Döpfner, Berner, Schmeck, Lehmkuhl, Poustka and Sergeant25 We received official permission by the state's school authority to contact the school teachers of our participants. Mothers signed a release from the pledge of secrecy so that we could contact teachers directly instead of having the questionnaires delivered by the mothers of the children, which could have caused bias.

Data analytic plan

We conducted a path analysis to investigate the multiple associations of our variables according to our hypotheses. We controlled for age of mother and child, gender of child, mother's years of education and presence of acute DSM-IV axis I disorders (other than MDD) in mothers. To address our research questions, we evaluated the statistical significance of each of the paths of interest and their indirect associations with each other. We started by fitting a full, less-restrictive model (see Fig. 1) to the data to determine which paths were significant and then removed non-significant paths to obtain our final, most parsimonious model. Model fit was evaluated by a combination of fit indices, including a non-significant χ2 test result (P < 0.05) and cut-off values close to 0.06 for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), close to 0.08 for the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) and 0.95 for the comparative fit index (CFI) as recommended by Hu and Bentler.Reference Hu and Bentler26 We applied a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors and a mean- and variance-adjusted test statistic, as implemented in the lavaan package, because CAPI scores were not normally distributed (skewness z-score >1.96). Finally, we estimated the relevant indirect effects in the model for significance according to P-values and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals, adjusting for both bias and skewness in the bootstrap sample's distribution.

This study initially involved 183 mother–child dyads. Because not all teachers returned the TRF forms and a few mothers did not return their questionnaire sets, 114 dyads entered the described analysis. Missing data were unrelated to any of the maternal risk factors evaluated (diagnoses of BPD and rMDD and severity of ELM) in our analysis. We conducted a series of multiple regressions – in which each predictor was regressed on all other predictors – before running our path analyses and we found no signs of multicollinearity.

We addressed issues of sample-size limitations as recommended by SteinmetzReference Steinmetz27 and Kieffer et al.Reference Kieffer, Vukovic and Berry28 Following the approach by Muthen and Muthen,Reference Muthen and Muthen29 we conducted a post hoc Monte Carlo simulation (10 000 replications) for sample size estimation in structural equation modeling (SEM) to assess potential bias of parameter estimates and standard errors, and to assess statistical power of the relations in our model. Muthen and MuthenReference Muthen and Muthen29 give precise cut-off criteria for parameters and standard error bias (10%), standard error bias for parameters of interest for which power is assessed (5%) and coverage (remaining between 0.91 and 0.98). They also refer to the commonly accepted value for power (0.80). We applied Swain'sReference Swain30 correction of the maximum likelihood χ2 statistic for the estimation of CFI and RMSEA, which accounts for the potential negative impact of sample size on fit statistics.

Descriptive analyses were executed in IBM SPSS Statistics version 23. Path analysis, sample size corrections of fit indices and Monte Carlo simulation were realised in The R Project for Statistical Computing (R) software using the packages lavaan, simsem and the public R function swain.

Results

Hypothesis 1

The analysis of the original (less-restrictive) path model (Fig. 1) yielded the following results: Maternal history of ELM (sum severity score) showed a direct effect on abuse potential (β = 0.241, P = 0.043). Diagnoses of maternal BPD and rMDD were not directly associated with abuse potential (β = 0.118, P = 0.320 and β = 0.188, P = 0.060, respectively), but showed an indirect link with abuse potential via emotion regulation difficulties (see Hypothesis 2).

Hypothesis 2

Maternal diagnoses of BPD and rMDD were significantly associated with the severity of maternal emotion regulation difficulties (β = 0.388, P = 0.002 and β = 0.289, P = 0.007), which was significantly associated with abuse potential scores (β = 0.195, P = 0.046). The indirect effects from BPD (unstandardised indirect effect coefficient B (s.e.) = 12.92 (5.70), β = 0.119, P = 0.023, bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap 95% CI [1.76; 24.09]) and rMDD (B(s.e.) = 7.55 (3.50), β = 0.090, P = 0.031, BCa 95% CI [0.69; 14.41]) through emotion regulation difficulties on child abuse potential were both significant with P < 0.05 and a confidence interval entirely above zero. Severity of maternal ELM was not associated with maternal difficulties in emotion regulation (β = 0.112, P = 0.312). In a supplemental analysis, we tested which subscales of emotion regulation difficulties showed significant correlations with abuse potential. We found significant associations of emotional awareness, emotional clarity, emotion regulation strategies and acceptance of emotional responses with abuse potential (Supplementary Table S1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.74).

Hypothesis 3

We found a significant association between abuse potential and child problem behaviour (β = 0.335, P < 0.001). The indirect effect of severity of ELM by way of child abuse potential on child problem behaviour (B(s.e.) = 0.21 (0.11), β = 0.084, P = 0.063, BCa 95% CI [−0.01; 0.43]) showed a trend towards significant with P < 0.10. The indirect effects from diagnosis of BPD (B(s.e.) = 0.94 (0.49), β = 0.036, P = 0.057, BCa 95% CI [−0.03; 1.91]) and rMDD (B(SE) = 0.55 (0.30), β = 0.027, P = 0.062, BCa CI 95% [−0.03; 1.13]) through severity of emotion regulation difficulties and child abuse potential to child problem behaviour were also trend-wise significant.

Final model

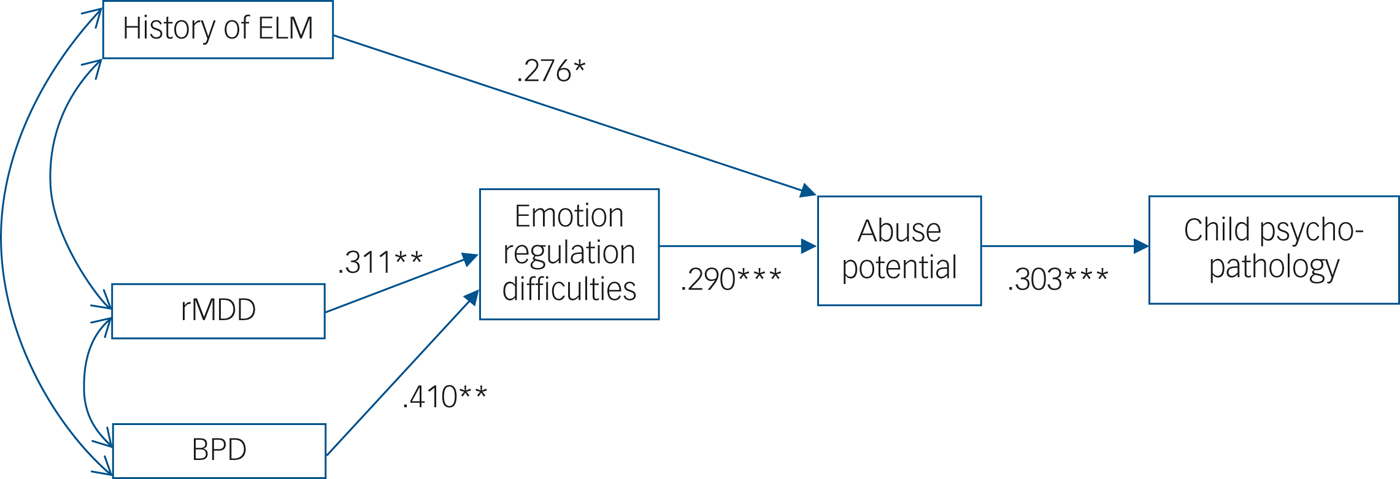

Table 2 shows associations of exogenous (predictor) and endogenous (outcome) variables and demographic control variables in our model. Non-significant paths were removed from the final model (Fig. 2) to obtain the most parsimonious model. Regarding the following fit indices, we conclude that our final model holds good fit according to the recommended cut-offs mentioned above: SRMR = 0.028, RMSEA = 0.059, CFI = 0.951, χ2 = 9.749, d.f. = 7 and P (χ2) = 0.203. Swain-corrected indices (for small sample sizes) yielded similar results with RMSEA = 0.056 and CFI = 0.963. A post hoc Monte Carlo simulation based on the results in our final path model revealed minimal bias in parameter estimates (between 0% and 2.0%), meeting the standard of <10%.Reference Muthen and Muthen29 Standard error bias ranged from 0.3% to 2.7%, meeting the standard of <5%. Coverage ranged from 0.92 to 0.94, thus falling into the recommended range of 0.91–0.98. Additionally, we found sufficient power for relevant relations in our final path model with all values >0.80. Therefore, there is little reason to suspect bias in parameter estimates and standard errors, or insufficient statistical power in our model due to small sample size. Our final model accounted for 15.2% of the variance in child problem behaviour, 23.9% of variance in child abuse potential, and 30.8% of variance in emotion regulation difficulties.

Fig. 2 Standardised path coefficients for tested paths of the final model. Only significant paths are displayed. Controlled for maternal and child age, gender of child, mother's years of education and mother's acute axis I disorders. Bidirectional arrows indicate covariance between two variables and one-directional arrows indicate a directional relationship. Covariation between early life maltreatment (ELM), bipolar disorder (BPD) and major depressive disorder in remission (rMDD) was an intended result of our recruitment strategy which aimed at including considerable numbers of mothers with either zero, one, two or three risk factors. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Table 2 Intercorrelations among key study variables and demographic variables

ELM, early life maltreatment; rMDD, major depressive disorder in remission; BPD, borderline personality disorder.

a. Point-biserial correlation coefficient.

b. Phi coefficient.

c. Pearson's r correlation coefficient.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

The main findings of our study are as follows: First, all three risk factors – i.e. severity of ELM, diagnosis of BPD and diagnosis of rMDD – were directly or indirectly associated with elevated abuse potential scores. Second, the effects of BPD and rMDD on abuse potential were mediated by severity of emotion regulation difficulties. Finally, we found a positive association between abuse potential and child psychopathology. Our study extends existing researchReference Hiraoka, Crouch, Reo, Wagner, Milner and Skowronski4–Reference Shay and Knutson6 in that we considered ELM, BPD and rMDD in one study and thus disentangled their individual contributions to abuse potential. We show that the previous finding of emotion regulation as a mediator for ELM and abuse potential seems to be related to co-occurring psychiatric disorders like BPD or MDD. In addition, this is the first study to identify emotion regulation difficulties as a mediator for rMDD and abuse potential. By showing that composite measures of child abuse potential have an impact on child mental health, we extend prior research linking substantiated maltreatment with child psychopathology. The following illuminates these major findings and their implications in more detail.

Effects on abuse potential and the meditating role of emotion regulation

According to our findings, severity of emotion regulation difficulties mediates the effect of BPD on abuse potential scores. This is in line with results showing that the effect of elevated BPD features on abuse potential was mediated by emotion regulation.Reference Hiraoka, Crouch, Reo, Wagner, Milner and Skowronski4 In addition, the present work considers ELM which is a frequent precursor of BPD. Deficits in emotion regulation is one of the most prominent features of BPD.Reference Glenn and Klonsky31 Although depression is primarily associated with other characteristics, emotion regulation problems also play a significant role in this type of disorder.Reference Joormann and Stanton7 In our study, emotion regulation difficulties emerged as a mediator for the association of maternal rMDD with abuse potential. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating emotion regulation as a pathway from MDD to abuse potential.

Our findings indicate that emotion regulation difficulties partially mediated the effect of ELM severity on abuse potential when excluding BPD and rMDD from the model (Supplementary Figure S1). In a more comprehensive path analytic model (including BPD and rMDD), however, severity of ELM was directly linked to abuse potential, although no association with emotion regulation difficulties emerged. This suggests that the mediation effect previously observed by Smith et al.Reference Smith, Cross, Winkler, Jovanovic and Bradley5 was, at least in part, related to co-occurring psychiatric disorders like BPD or MDD. In our data, there was no indirect effect of ELM on abuse potential via emotion regulation independent of BPD and rMDD.

Future research may address additional factors mediating the severity of ELM and abuse potential, including maternal knowledge of child development and behaviour, which has previously been associated with abuse potential.Reference Fulton, Murphy and Anderson32 Attitude towards parenting will also be of interest in the future, as attitude was found to influence the effect of parenting stress on abuse potential.Reference Crouch and Behl33

Emotion regulation may be a target of intervention in prevention programs for mothers with BPD and MDD. The highest associations of abuse potential with emotion regulation difficulties were found in the areas of emotional awareness, emotional clarity, emotion regulation strategies and acceptance of emotional responses (Supplementary Table 1). These aspects of emotion regulation could be targeted in special interventions catering to parents. Mothers with a history of ELM may benefit from such interventions when they also show signs of BPD and MDD. However, there appear to be other aspects that mediate effects of ELM on child abuse potential that remain to be explored.

Maternal abuse potential and child mental health

Our finding that maternal abuse potential scores predicted child psychopathology confirms the final hypothesis, extending the existing literature on the association of child abuse and impaired child mental health.Reference Jaffee8, Reference Haskett, Scott and Fann9 Haskett et al.Reference Haskett, Scott and Fann9 studied samples of parents who had either been identified as high risk for abuse or had substantiated cases of physical abuse. Substantiated maltreatment rates and assessment of abuse potential are the two methodological approaches applied most often when exploring the risk for child abuse in parents. Substantiated cases of maltreatment may reflect only a proportion of maltreating parents as an underreporting of these problems is expected.Reference Cross and Casanueva34 The risk measures of child abuse attempt to sidestep this distortion of data: the parental risk of maltreating their offspring is measured by assessing psychosocial characteristics associated with violence against children, as for example with the CAPI.Reference Milner19 Haskett et al.Reference Haskett, Scott and Fann9 found an association of abuse potential and child psychopathology measured with a parent rating questionnaire, but no association with child psychopathology in a teacher rating was found. Ratings of child psychopathology by parents with high risk for abuse may be biased, however, and the investigation's sample was small (n = 41), focusing on substantiated cases of abuse (n = 25). Our findings regarding a teacher rating of child psychopathology underline the relevance of abuse risk measures for child mental health. The CAPI includes multiple parental aspects that have been found to predict child abuse, including global distress, rigidity (parenting and expectation to child), perception of the child as a ‘problematic child,’ restricted physical health, unhappiness with one's own life and interpersonal relationships, problems with family, problems with self, emotional lability, lack of social support and feelings of loneliness. Such familial or parental distress may impair child well-being even though actual acts of abuse do not take place.

Indirect effects leading from BPD and rMDD diagnoses to child psychopathology via emotion regulation and abuse potential showed a trend towards significance. Likewise, an indirect effect of ELM severity via abuse potential on child psychopathology was found to have a trend towards significance. These results indicate that the pathways studied here may be relevant for intergenerational processes of transmission.

Limitations

This study has limitations: First, we only studied mothers even though paternal factors may also play an important role for child abuse potential. Second, we did not directly assess substantiated cases of child abuse. However, solely studying substantiated cases of child abuse might lead to underreporting problems, as not all abusive behaviours are reported to officials.Reference Cross and Casanueva34 Third, MDD and BPD are common reactions to ELM experiences, but they may only represent a limited range of psychiatric disorders associated with ELM. Fourth, the results reported are based on a cross-sectional study design and thus a causal conclusion cannot be made. Fifth, there might be other important factors, like family and child characteristics, affecting child mental health that we could not consider in our model. These factors could be realised in studies with very large sample sizes. Sixth, we used a teacher rating of child mental health, in contrast to a parent rating, to reduce the issue of common-method variance. However, teachers might have a different or even reduced picture of child behaviour. Fifth, although the proportion of mothers with at least moderate ELM and rMDD was balanced, it is acknowledged that the number of mothers with BPD was relatively low. Thus, the effects of maternal BPD need to be replicated in larger samples in future studies. Sixth, we did not test inter-rater reliability of the IPDE (diagnostic interview) within our study team. Finally, our sample size was limited for path analytic modelling. Potential issues with smaller sample sizes in SEM of path analysis include limitations in statistical power, bias in parameter estimates, standard errors and goodness-of-fit statistics.Reference Kieffer, Vukovic and Berry28, Reference Muthen and Muthen29 To cope with this limitation, we performed a post hoc Monte Carlo simulationReference Muthen and Muthen29 and applied Swain'sReference Swain30 correction of the maximum likelihood χ2 statistic.

We conclude that ELM directly affects risk for child abuse and child well-being, although MDD and BPD indirectly affect these factors via emotion regulation. Prevention and intervention programs could address emotion regulation issues for mothers diagnosed with BPD or MDD. Further research is needed to identify other transmitting factors, especially in mothers with ELM who do not have BPD or MDD.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (grant number: 01KR1207C) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) (grant number: BE2611/2-1).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.74.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.