Chinese medicine, now commonly referred to as ‘traditional Chinese medicine’ has been used to treat schizophrenia-like illness for over 2000 years (Reference MingMing, 2001). Although antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay of treatment both in China and in the West, they are associated with serious adverse effects such as tardive dyskinesia and tremor. In addition, about 20% of people do not respond adequately to treatment (Reference Brenner, Dencker and GoldsteinBrenner et al, 1990). Some earlier reports have suggested that Chinese herbal medicine is effective for psychosis and that combination treatments (drugs plus herbs) are useful to enhance antipsychotic efficacy or reduce the period of recovery and adverse effects (Reference SakuSaku, 1991; Reference WangWang, 1998a ).

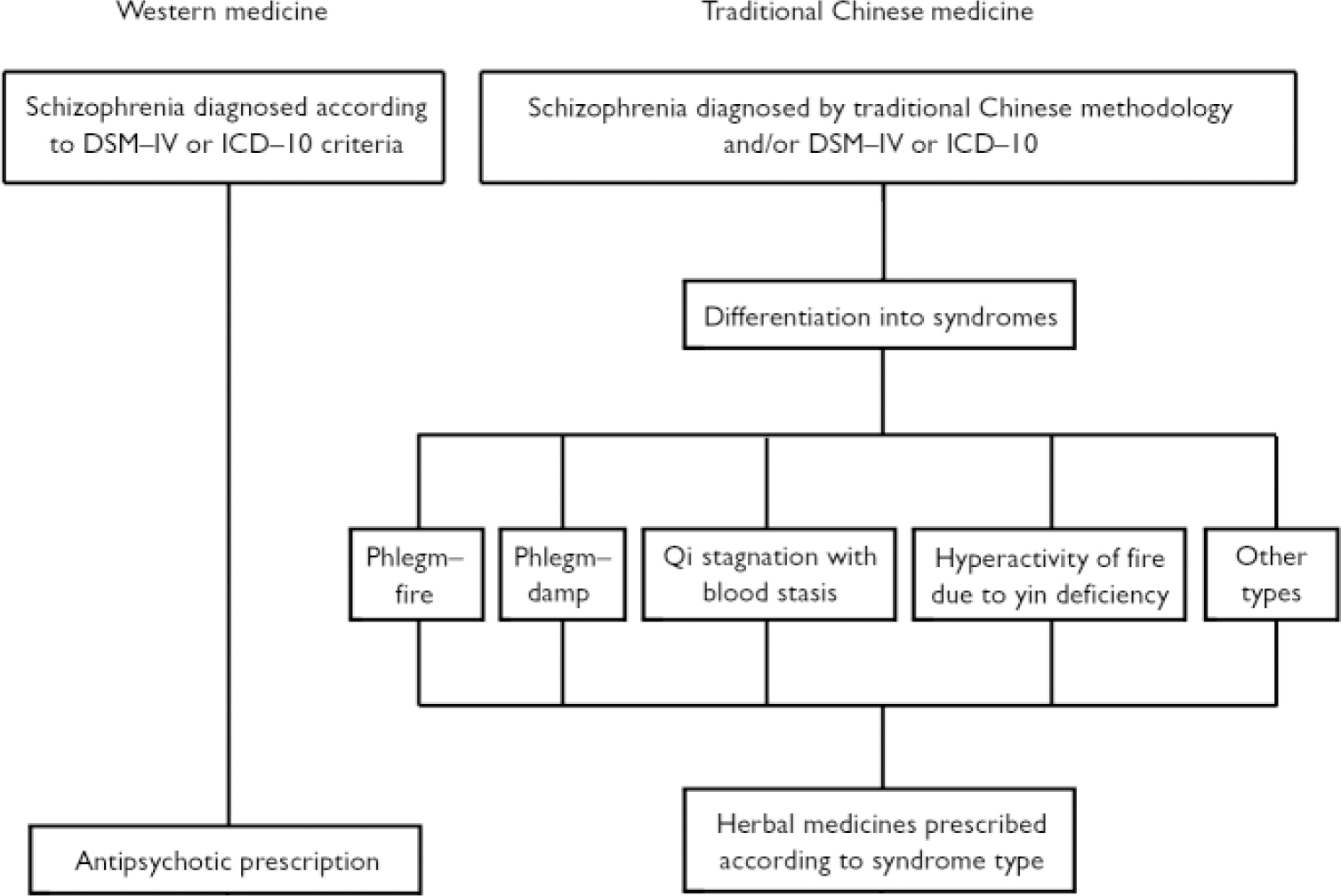

The methodology used in traditional Chinese medicine to diagnose and treat schizophrenia differs from that used in Western medicine. Traditional Chinese medicine differentiates cases of schizophrenia into syndromes, and it is these syndromes rather than the disease label such as schizophrenia or dian kuang (withdrawal mania), that determine treatment (Fig. 1). There are five main syndromes that fall within the disease category of dian kuang which may also include the Western diagnosis of schizophrenia. The five types are:

-

(a) phlegm-fire;

-

(b) phlegm-damp;

-

(c) qi stagnation with blood stasis;

-

(d) hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency;

-

(e) other miscellaneous types (Reference ZhangZhang, 1996).

Each syndrome has a specific herbal formulation, but patients typically have mixed clinical presentations requiring formulas to be adapted by adding or subtracting herbs. To complicate matters, in China herbal medicines are sometimes used within the Western diagnostic paradigm alone without incorporating traditional theory. Nevertheless, because of the enormous population of China, even if herbal medicines are given to only a small proportion of the estimated 13 million Chinese people with schizophrenia, these treatment approaches could still be some of the most prevalent used for this illness.

METHOD

Full details of all methods used and the predefined inclusion criteria are published elsewhere (Reference Rathbone, Zhang and ZhangRathbone et al, 2005). Randomised controlled trials were included if participants had schizophrenia, schizophreniform psychosis or a schizophrenia-like illness, diagnosed by any criteria. Interventions included Chinese herbal medicines (plant, animal or mineral) given in any dosage or combination, with or without a basis in traditional Chinese medical theory, compared with any other approach.

Studies were identified from searches of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's register of trials, which incorporates regular searches of BIOSIS Inside, CENTRAL, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO; the hand-searching of relevant journals and conference proceedings and searches of several grey literature sources. Additional databases searched included the Traditional Chinese Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System, the Chinese Biomedical Database, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure database and the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED). Full details of the English and Mandarin phrases used are reported elsewhere (Reference Rathbone, Zhang and ZhangRathbone et al, 2005).

Data were not utilised from studies in which more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow-up (this does not include the outcome of ‘leaving the study early’). In studies with a less than 50% withdrawal rate people leaving the study early were considered to have had the negative outcome, except for the event of adverse effects and death. For binary outcomes, the fixed-effects relative risk and its 95% confidence interval were calculated. The numbers needed to treat/harm (NNT/NNH) were also calculated. An estimate of the weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups and its 95% confidence interval were calculated for continuous data. Data were not pooled if standard deviations were too wide, suggesting considerable skew (Reference Altman and BlandAltman & Bland, 1996). Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by inspecting the relevant graph; this was supplemented using the I 2 statistic (Reference Higgins, Thompson and DeeksHiggins et al, 2003). If inconsistency was high (⩾75%), the data were not pooled but were presented separately and the reasons for heterogeneity investigated.

Fig. 1 Diagnosis and treatment plan for schizophrenia in Western and traditional Chinese medicine.

Citations were inspected independently by at least two reviewers. The reliability of the data extraction was checked using a 10% sample. Full reports of studies of agreed relevance were obtained, quality-rated (Reference Alderson, Green and HigginsAlderson et al, 2004) and data extracted for details of methods, participants, interventions and outcomes. Disagreements between reviewers were discussed and if they could not be resolved further information was sought from authors. Main outcomes of interest were predefined as clinical response in global or mental state, adverse events including extrapyramidal adverse effects, service use including hospitalisation and relapse, quality of life, leaving the study early, death and economic evaluations.

RESULTS

Electronic searches resulted in over 640 citations but most clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. Full copies of only 14 studies were obtained, of which we could include 7 (Table 1). Of those we excluded, three were not randomised (Reference Cao and WangCao & Wang, 2000; Reference Gong, Zu and JinGong et al, 2000; Reference RongRong, 2001), three did not report usable data (Reference Zhao, He and LuoZhao et al, 1997; Reference WangWang, 1998b ; Reference Han, Zhang and LiuHan et al, 2002) and one study did not use Chinese herbal medicine (Reference Zhen and FengZhen & Feng, 1992).

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

| Included studies | Methods | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of study | First author | Number of publications | Double-blind | Setting | Duration (weeks) | History | n | Age (years) | Gender | Experimental group | Control group | Leaving study early | Global state | Mental state | Adverse effects | |||||||||||

| 1987 | Zhang | 2 | NK | H | 2.9 | FE | 90 | 16–51 | NK | DGCQT 50 ml b.i.d. (n=45) | Chlorpromazine, as required (n=45) | Yes | Yes | No | No | |||||||||||

| 1996 | Meng | 1 | Yes | H | 8 | NK | 40 | 18–60 | M, F | Ginkgo biloba 1 240 mg/day + antipsychotics (n=21) | Placebo + antipsychotics 2 (n=19) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |||||||||||

| 1996 | Zhu | 1 | OL | H | 4.3 | NK | 67 | 17–53 | F | Hirudo & Rheum palmatum 2 + chlorpromazine, 300 mg/day (n=32) | Chlorpromazine, 400 mg/day (n=35) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

| 1997 | Chen | 2 | SB | H | 26.1 | CI | 120 | 27–58 | NK | Xingshen + antipsychotics 3 , 300–700 mg/day (n=60) | Antipsychotics 3 , 250–800 mg/day (n=60) | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||||||||

| 1997 | Luo | 3 | Yes | H | 16 | NK | 545 | 18–60 | M, F | Ginkgo biloba 1 , 120 mg t.d.s. + antipsychotics (n=315) | Placebo + antipsychotics 4 (n=230) | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||||||||

| 1997 | Zhang | 1 | OL | H, C | 12 | CI | 123 | Mean 32 | M, F | DGCQT or XYS, 200–300 ml/day + antipsychotics 2 (n=66) | Antipsychotics 2 (n=57) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

| 2001 | Zhang | 6 | Yes | H | 12 | CI | 109 | 27–61 | M, F | Ginkgo biloba 1 , 360 mg + haloperidol 0.25 mg/kg per day (n=56) | Haloperidol, 0.25 mg/kg per day + placebo (n=53) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

C, community; CI, chronic illness; DGCQT, dang gui cheng qi tang; F, female; H, hospital; M, male; NK, not known; OL, open lable; SB, single-blind; XYS, xiao yao san

1. Standardised extract of Ginkgo biloba (EGb761)

2. No further details on medicine and/or dosage

3. Chlorpromazine, clozapine, sulpiride

4. Clozapine, chlorpromazine, sulpiride, perphenazine and haloperidol

We identified 16 citations dating from 1987 to 2002 for the seven included studies. Overall, descriptions of studies were poorly reported. Two trials were available in both Chinese and English (Reference Luo, Shen and MengLuo et al, 1997; Reference Zhang, Zhou and ZhangZhang et al, 2001), four in Chinese only (Reference Meng, Cui and WangMeng et al, 1996; Reference Zhu, Kang and ZhuZhu et al, 1996; Reference Chen, He and ChenChen et al, 1997; Reference Zhang, Zhou and JinZhang et al, 1997) and one in English only (Reference Zhang, Tang and ZhuZhang et al, 1987). All seven included studies were conducted in China and were described as being randomised, but none gave a description of the allocation procedure. Double-blind methodology was used in three studies, all of which used Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb761) combined with antipsychotics. All trials included in this review contained a moderate risk of bias (category B; Reference Alderson, Green and HigginsAlderson et al, 2004). Trials ranged in sample size from 40 to 545 participants and lasted from 20 days to 6 months. Only one study (Reference Zhang, Zhou and JinZhang et al, 1997) attempted to allocate treatment according to traditional Chinese medicine syndrome differentiation. The other six studies employed Western diagnoses of schizophrenia with no further differentiation into the traditional Chinese syndromes, and six used operational diagnostic criteria. Three studies included people with chronic schizophrenia (mean duration 17 years), three did not report participants' history of illness and one study involved mostly people at first admission to hospital.

Herbal medicine alone v. chlorpromazine

Only one study (Reference Zhang, Tang and ZhuZhang et al, 1987) gave the treatment group herbal medicines without the addition of an antipsychotic. Over a 20-day period, global state outcome ‘not improved/worse’ significantly favoured the control group receiving chlorpromazine (n=90; RR=1.88, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.9, NNH=4, 95% CI 2 to 14). No participant left the study early.

Herbal medicine plus antipsychotics v. antipsychotics alone

Herbal medicines given according to traditional Chinese medicine syndrome differentiation – in only one study (Reference Zhang, Zhou and JinZhang et al, 1997), using dang gui cheng qi tang or xiao yao san – when combined with antipsychotic medication (unspecified) scored significantly lower for the outcome of global state ‘not improved/worse’ than the control group given unspecified antipsychotics (NNT=6, 95% CI 5 to 11; Fig. 2(a)). Further global state data from the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale – Meng et al (Reference Meng, Cui and Wang1996), unknown antipsychotic; Zhu et al (Reference Zhu, Kang and Zhu1996), chlorpromazine – also favoured the herbal medicine plus antipsychotic group (Fig. 2(b)).

Zhang et al (Reference Zhang, Zhou and Zhang2001) found Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scores dichoto-mised to ‘not improved/worse’ were equivocal (n=109, RR=0.78, 95% CI 0.5 to 1.2) when Ginkgo biloba plus haloperidol were compared with haloperidol, as were data from the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (n=109, RR=0.87, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.2). However, the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) did slightly favour the herbal medicine plus haloperidol combination (n=109, RR=0.69, 95% CI 0.5 to 1.0; NNT=6, 95% CI 4 to 162). Continuous short-term BPRS data – Meng et al (Reference Meng, Cui and Wang1996), unknown antipsychotic; Zhu et al (Reference Zhu, Kang and Zhu1996), chlorpromazine – significantly favoured the herbal medicine plus antipsychotic combination (Fig. 2(c)), but data were heterogeneous (I 2=81%). Medium-term BPRS data (Fig. 2(c)) also favoured the herbal medicine plus antipsychotic combination: Luo et al (Reference Luo, Shen and Meng1997), antipsychotics clozapine, chlorpromazine, sulpiride, perphenazine and haloperidol; and Zhang et al (Reference Zhang, Zhou and Zhang2001), haloperidol (n=621, WMD= –4.17, 95% CI –5.5 to –2.8). Medium-term SANS scores (Fig. 2(d)) significantly favoured the herbal medicine plus antipsychotic group.

Fig. 2 Comparison of herbal medicine + antipsychotic v. antipsychotic (BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; NNT, number needed to treat; RR, relative risk; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; WMD, weighted mean difference).

Adverse events are associated with antipsychotic medication, and combining herbal medicines with chlorpromazine (Reference Zhu, Kang and ZhuZhu et al, 1996) did not mitigate extrapyramidal adverse effects, with both groups being equivocal. Constipation, however, was significantly lower in the herbal plus antipsychotic combination group (0/32) despite patients receiving the constipating antipsychotic chlorpromazine (n=67; RR=0.03, 95% CI 0.0 to 0.5; NNH=2, 95% CI 2 to 4); the comparison group (chlorpromazine alone) fared less well (19/35). Medium-term studies found significantly fewer patients leaving the study early (Fig. 2(e)) in the herbal plus antipsychotic group (n=897, four RCTs, RR=0.34, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.7; NNT=23, 95% CI 18 to 43).

Sensitivity analysis: Ginkgo biloba alone or plus antipsychotics v. antipsychotics

Studies of Ginkgo biloba were tested in a sensitivity analysis by comparing them with the original pooled data (Ginkgo biloba data pooled with other herbs). Effect sizes for CGI and BPRS scores were increased for Ginkgo biloba when analysed separately, although these differences were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Six of the seven studies evaluated the use of Chinese herbs for schizophrenia rather than traditional Chinese herbal medicine for schizophrenia, i.e. treatment was allocated according to a diagnosis of schizophrenia without further differentiation according to traditional Chinese methodology. Study sizes were generally small and pooled data were typically derived from one or two studies. All outcomes, therefore, were underpowered. The one study that incorporated traditional Chinese medical theory did show significant improvement in global state but was limited by lack of blinding. There were no descriptions of allocation concealment and no assurances that blinding was maintained. The type of antipsychotic used and the dosages were often poorly reported, although three studies used the same herbal intervention – Ginkgo biloba (EGb761). The remainder, however, used different herbal medicines, and unfortunately all three Ginkgo biloba studies used different antipsychotic medications.

Herbal medicine alone v. antipsychotics

Global state measured as ‘not improved/worse’ favoured the chlorpromazine group (NNT with chlorpromazine 4, 95% CI 2 to 14) when compared with the treatment group receiving dang gui cheng qi tang. This NNT concurs with findings when chlorpromazine is compared with placebo (Reference Adams, Awad and RathboneAdams et al, 2007); however, this is based on a single study (n=90; Reference Zhang, Tang and ZhuZhang et al, 1987) lasting 20 days with participants given Chinese herbs according to a diagnosis of schizophrenia without using traditional Chinese medicine differentiation. Results must therefore be interpreted with caution given the design limitations, but nevertheless do not support dang gui cheng qi tang as a sole treatment for schizophrenia.

Herbal medicine plus antipsychotics v. antipsychotics alone

The herbal medicine group receiving either dang gui cheng qi tang or xiao yao san plus antipsychotics were significantly less likely to have an outcome of ‘no change or worse’ compared with participants receiving only antipsychotics, measured using the Clinical Global Impression scale (NNT=6, 95% CI 5 to 11). This could be an important finding and does fit with the CGI continuous scores. These results are broadly encouraging and suggest that combining herbal medicines with antipsychotics might be beneficial, although results are only based on two small studies (total n=103). These vaguely positive finding also apply to mental state outcomes. The dichotomised BPRS and SANS measures reported by Zhang et al (Reference Zhang, Zhou and Zhang2001); n=109) were equivocal, but SAPS scores again showed borderline significance in favour of the herbal medicine plus antipsychotic combination. Medium-term continuous SANS data, however, provided more robust results, with three studies (n=741) favouring the herbal plus antipsychotic combination group. The experimental group had, on average, nine points less on this scale than those allocated to antipsychotic drugs alone. In our opinion, in this group of chronically unwell people such an average difference would be noticeable and clinically meaningful. Further supporting this improvement, both short-term and medium-term BPRS scores were significantly better for those receiving herbal medicines plus antipsychotics compared with those receiving antipsychotic drugs alone, although there was heterogeneity in these results. The latter might have been due to the use of different antipsychotic drugs between trials.

Adverse effect Treatment Emergent Signs and Symptoms scores were reported by Zhang et al (Reference Zhang, Zhou and Zhang2001), but standard deviations were wide and no conclusion can be made with confidence. Only one study (Reference Zhu, Kang and ZhuZhu et al, 1996; n=67) reported extrapyramidal symptoms, and these were not significantly different between groups. In one trial in which both groups were given chlorpromazine, constipation was significantly more frequent in the control group (NNH=2). In this trial the herb used was a purgative used also in Western medicine – Rhizoma rhei palmatum (rhubarb).

Numbers of participants leaving the study early in the short term were similar for both groups. Medium-term data showed significantly fewer left early in the herbal medicine plus antipsychotic group compared with people receiving only antipsychotics (n=897; 2% v. 7%). In the context of these studies, the addition of herbal medicine did not worsen treatment compliance and there is the suggestion that the addition of the herbal medicine made it easier for participants to take standard antipsychotics.

We did a post hoc sensitivity analysis for the single herb Ginkgo biloba, used outside the traditional Chinese medicine approach within a Western model of schizophrenia. We found no evidence that this particular herb had remarkable effects.

The application of traditional Chinese herbal medicine is fundamentally interwoven with syndrome differentiation. Failure to apply syndrome differentiation may result in treatments being ineffective or even harmful. Despite this, there is some evidence that these Chinese herbal medicines, combined with antipsychotics and given in a way that is not in keeping with their normal use within traditional Chinese medicine, may be beneficial for people with schizophrenia across a range of outcomes. If these medicines are used within their usual context the positive effects could be greater. Even the gains seen in this review would still be important for the millions for whom these treatments are used. Both West and East need well-reported (Reference Moher, Schulz and AltmanMoher et al, 2001) randomised trials that are adequately powered, blinded and of sufficient duration so we can detect meaningful treatment effects with high levels of confidence.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.