Cognitive decline refers to a wide continuum of changes in cognitive function across the life course, including both age-related decline and pathological decline. Reference Plassman, Williams, Burke, Holsinger and Benjamin1 Poor cognitive status, even in the absence of clinical dementia, is perhaps the single most disabling condition in old age. Dementia is a syndrome characterised by impairment of multiple cognitive capacities that are severe enough to interfere with daily functioning. It is often preceded by mild cognitive impairment, defined as ‘cognitive impairment short of dementia’ or as ‘a transitional state between normal cognition and dementia’. Reference Steffens, Otey, Alexopoulos, Butters, Cuthbert and Ganguli2 It is estimated that pathological changes that lead to dementia start as early as several decades before clinical diagnosis. Reference Singh-Manoux, Kivimaki, Glymour, Elbaz, Berr and Ebmeier3,Reference Elias, Beiser, Wolf, Au, White and D'Agostino4 An effective cure for dementia remains elusive and given high and rising treatment and care costs, knowledge about early modifiable risk factors may be important from a public health perspective. Importantly, unhealthy behaviours may accelerate cognitive decline and be amenable to low-cost intervention at a population level. Reference Brayne5 In the UK, cigarette smoking and heavy alcohol consumption remain prevalent, including among older adults. 6

Several studies have found an association between smoking and cognitive decline Reference Peters, Poulter, Warner, Beckett, Burch and Bulpitt7-Reference Sabia, Elbaz, Dugravot, Head, Shipley and Hagger-Johnson9 and dementia. Reference Anstey, von Sanden, Salim and O'Kearney8 Earlier studies apparently suggesting a protective effect of smoking Reference Graves, van Duijn, Chandra, Fratiglioni, Heyman and Jorm10,Reference Lee11 were later attributed to selection bias. Reference Garcia, Ramon-Bou and Porta12 Evidence concerning alcohol use as a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia is also mixed. There may be non-linear associations between alcohol and cognitive outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis found lower risk of dementia in people who were moderate (for example up to 14 units per week for women and up to 21 units per week for men) but not heavy drinkers compared with non-drinkers. Reference Anstey, Mack and Cherbuin13 Smoking and heavier alcohol consumption often co-occur Reference Poortinga14 and their combined effect on cognition may be larger than the sum of their individual effects. In combination they have been associated with greater risk of all-cause mortality in an occupational cohort in West Scotland Reference Hart, Davey Smith, Gruer and Watt15 and with aerodigestive cancer risk in a meta-analytic study. Reference Zeka, Gore and Kriebel16 To date few studies have examined the combined effect of smoking and alcohol use on cognitive decline. In two early cross-sectional studies of community-dwelling older adults in the USA (age 60-84), one found no greater combined effect Reference Schinka, Vanderploeg, Rogish, Graves, Mortimer and Ordoric17 and the other found general cognitive function to be 6% lower among those who smoked and drank alcohol heavily compared with all other groups. Reference Schinka, Belanger, Mortimer and Graves18 An earlier study of older adults in the USA (age 65 and older) found no separate effects but did not test for a possible interaction. Reference Herbert, Scherr, Beckett, Albert, Rosner and Taylor19 A later study in Finland found more frequent (v. never or infrequent) alcohol use in midlife was associated with better cognitive performance 21 years later (at age 65-79), which was stronger among non-smokers. Reference Ngandu, Helkala, Soininen, Winblad, Tuomilehto and Nissinen20

The evidence from studies on older populations on the combined effect of alcohol and smoking on the risk of cognitive function, Reference Schinka, Vanderploeg, Rogish, Graves, Mortimer and Ordoric17,Reference Schinka, Belanger, Mortimer and Graves18,Reference Ngandu, Helkala, Soininen, Winblad, Tuomilehto and Nissinen20 cognitive decline, Reference Herbert, Scherr, Beckett, Albert, Rosner and Taylor19,Reference Leibovici, Ritchie, Ledésert and Touchon21 or later Alzheimer's disease Reference Garcia, Ramon-Bou and Porta12,Reference Tyas, Koval and Pederson22 is inconsistent. An added complication is that older smokers are a selected population. Reference Sabia, Elbaz, Dugravot, Head, Shipley and Hagger-Johnson9 As cognitive decline is evident in midlife, Reference Singh-Manoux, Kivimaki, Glymour, Elbaz, Berr and Ebmeier3 the aim of our study was to examine whether cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption interact to accelerate cognitive decline in the transition from midlife to early old age.

Method

Study population

The Whitehall II cohort was established in 1985/88 among 10 308 British civil servants. Reference Marmot and Brunner23 All civil servants aged 35-55 years in 20 London-based departments were invited to participate by letter, and 73% agreed (67% men). Cognitive testing was introduced in 1997/99 (the baseline for our analysis) during a clinical examination when the cohort members were aged 45-69 and repeated at two subsequent clinical examinations in 2002/04 and 2007/09, Reference Marmot and Brunner23 providing a follow-up period of 10 years. All participants provided written consent and the University College London ethics committee approved the study.

Measures

Covariates were drawn from the 1997/99 wave: age, gender, educational attainment (none or lower primary school, lower secondary school, higher secondary school, university, higher university degree), chronic disease up to and including baseline (physician diagnosed cancer, coronary heart disease, stroke excluding transient ischaemic attack, diabetes) and a vocabulary score. Coronary heart disease was ascertained based on clinically verified events, including myocardial infarction and definite angina. Information on stroke events was obtained both from self-reports, and from 1989, hospital episode statistics records. Diabetes was defined as having fasting glucose ⩾7.0 mmol/l or a 2 h postload glucose ⩾11.1 mmol/l using a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test. Reference Alberti and Zimmet24 The Mill Hill Vocabulary Test consists of 33 stimulus words ordered by increasing difficulty and has six response choices. Reference Raven25

Data on cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption were obtained from questionnaires in 1985/88 (recruitment), 1991/93, 1997/99 (baseline cognitive assessment), 2002/04 and 2007/09. Participants were asked about their alcohol consumption in the past 7 days (measures of spirits, glasses of wine, pints of beer). They were classified as non-drinkers (0 units of alcohol per week), moderate drinkers (1-14 units a week for women or 1-21 units per week for men) or heavy drinkers (>14 units per week for women and >21 units per week for men). 26 Smoking status was classified as current smoker, ex-smoker or never smoker.

The cognitive test battery comprised four cognitive tests and was administered at three clinical examinations over 10 years (1997/99, 2002/04 and 2007/09).

-

(a) The Alice Heim 4-I (AH4-I) is composed of a series of 65 verbal and mathematical reasoning items of increasing difficulty to be completed in 10 min. Reference Heim27

-

(b) Short-term verbal memory was assessed with a 20-word free recall test. Participants were presented with a list of 20 one- or two-syllable words at 2 s intervals and then had to recall them in writing in 2 min.

-

(c) There were two tests of verbal fluency. Reference Borkowski and Spreen28 Participants were asked to recall in writing as many ‘S’ words (phonemic fluency) and as many animal names as they could (semantic fluency) in 1 min.

The four cognitive tests were combined to create a global cognitive z-score (mean 0, s.d. = 1), using the mean and standard deviations from 1997/99 for standardisation, providing that participants had completed at least two tests. Previous research has used global scores constructed in this manner to minimise problems due to measurement error on the individual tests. Reference Wilson, Leurgans, Boyle, Schneider and Bennett29 From 2002/04, the battery additionally included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh30 used to identify possible cases of cognitive impairment. Reference Anstey, Burns, Birrell, Steel, Kiely and Luszcz31

Statistical analysis

We used latent growth curve models Reference Bollen32 (also known as random-effects models) to examine both the cross-sectional and longitudinal association between individuals who were smokers (v. never smokers), ex-smokers (v. never smokers), heavy (v. moderate) or abstinent (v. moderate) alcohol users, and their interactions, and the global cognitive score. Latent growth curve models acknowledge that repeated measures on the same individual are correlated, and allow participants with incomplete follow-up data to be included in the analysis. Both the intercept and the slope are fitted as random effects, allowing each to vary between individuals, but without conditioning the slope on the baseline score. Reference Glymour, Weuve, Berkman, Kawachi and Robins33 We divided participants' time scores (in years) by 10 so that coefficients describe cognitive decline over 10 years. A model containing the alcohol consumption and smoking status variables (and covariates) and their product terms (alcohol consumption×smoking status) was compared with a nested model that only contained the exposure variables (and covariates), using a likelihood ratio test (a test of global interaction, also known as the chi-squared difference test) separately for the intercepts and slopes.

Older adults experience faster cognitive decline, Reference Singh-Manoux, Kivimaki, Glymour, Elbaz, Berr and Ebmeier3 allowing us to compare the effect of being in a particular ‘alcohol consumption× smoking status’ group with the effect of being 1 year older, providing information about clinical significance. The two effect sizes were compared using the formula (Bgroup/Bone year older = age effect).

The linear dose-response association between alcohol units and cigarettes was evaluated among males who were cigarette smokers and heavy drinkers respectively, given low statistical power among females who were smokers. To normalise the skewed distribution, alcohol units were natural log transformed (constant added) and consumption fitted using log units together with an intercept term indicating alcohol use v. non-use. Reference Kirkwood and Sterne34 The number of cigarettes smoked could not be normalised by transformation and was therefore grouped into 1-10, 11-20, 21+ cigarettes per day (v. none) to match clear peaks in the distribution at 10 and 20 cigarettes per day.

Several sensitivity analyses were performed. First, we repeated analyses among participants with an MMSE score of 24 or more Reference Anstey, Burns, Birrell, Steel, Kiely and Luszcz31 in 2002/04 and 2007/09 to ensure that results were not driven by possible cases of cognitive impairment. Second, we additionally adjusted results for the highest Mill Hill Vocabulary Test score obtained, to evaluate the impact of possible reverse causation. Reference Corley, Jia, Brett, Gow, Starr and Kyle35 Since vocabulary is resistant to cognitive decline, Reference Sabia, Elbaz, Dugravot, Head, Shipley and Hagger-Johnson9 it is often used as a measure of premorbid cognitive function. Third, we calculated a cumulative risk score for smoking, alcohol and their interaction from recruitment to baseline (1985/88, 1991/93 and 1997/99); to evaluate whether previous cumulative exposure was also associated with cognitive function and decline. Fourth, we evaluated the impact of behaviour change on results by excluding participants who changed their behaviour after baseline in 1997/99 (smokers who had stopped smoking or heavy alcohol drinkers who no longer drank heavily in 2002/04 and 2007/09). Fifth, we repeated the models after excluding participants who were very heavy drinkers (>35 units per week) 26 and heavy smokers (>20 cigarettes per day) at the same time, to evaluate their impact on results. Sixth, we added a term (male×smoking status) to the model to capture the previously reported association between current smoking and cognitive decline observed in men only, Reference Sabia, Elbaz, Dugravot, Head, Shipley and Hagger-Johnson9 to confirm results were consistent. Seventh, we repeated the models on each of the four cognitive tests, to evaluate whether patterns differed for memory compared with tests that involve executive function (reasoning, semantic and phonemic fluency). Eighth, we repeated the analysis on a nested sample of participants with complete data from baseline to follow-up. Similar results among those with complete v. missing data would provide evidence against a healthy-survivor effect. Finally, we also compared models including participants reporting no alcohol use in the past 7 days but regular use at other times (occasional drinkers) with those reporting no use at other times (non-drinkers), to evaluate whether heterogeneity in the ‘0 alcohol units per week’ group influenced our findings.

Results

The analytic sample comprised 6473 participants (4635 men) with data on cigarette smoking, alcohol units, covariates and global cognition for at least one examination. Of the analytic sample, 68.4% had three waves of cognitive data and 19.3% had two waves. Compared with the Whitehall II study population at recruitment (1985/88, n = 10 308) those excluded were slightly older (mean 44.8 v. 44.2 years in 1985-88, P<0.001), more likely to be female (41.1% v. 28.4%, P<0.001), more likely to smoke (24.7% v. 14.8%, P<0.001) and less likely to drink alcohol heavily (14.6% v. 16.3%, P<0.001). Table 1 presents characteristics of the participants included in the analysis, showing that individuals who were current smokers were more likely to drink alcohol heavily.

Growth curve models to estimate the combined effect of alcohol consumption and smoking status at baseline (1997/99) on global cognitive score over follow-up (2002/04 and 2007/09) were fitted with adjustment for age, gender, prevalent chronic disease and educational attainment. These models showed a significant interaction between smoking status and alcohol consumption, both for the intercept (cognitive function at baseline, χ2(4) = 20.83, P⩽0.001) and the slope (cognitive decline over 10 years, χ2(4) = 9.99, P = 0.04).

In order to estimate the combined effect of each alcohol× smoking status group, the model was re-parameterised and fitted using eight dummy variables that compared each alcohol×smoking status group with the largest group used as the reference group (never smoker, moderate alcohol drinker). This enabled estimation of the cognitive outcomes in each group in terms of cognition function in 1997/99 (intercept) and cognitive decline during the follow-up (slope). Table 2 shows the estimated mean intercept and slope for each alcohol×smoking status group (coefficients for the alternative parameterisation are shown in online Table DS1, and for all groups in online Table DS2). Compared with those who were never smokers and consumed a moderate amount of alcohol, participants reporting no alcohol consumption in the previous 7 days generally had worse cognitive function at baseline. Moderate drinkers who were current smokers also had a significantly lower baseline cognitive function. In general, estimated cognitive function at baseline was higher as alcohol consumption increased.

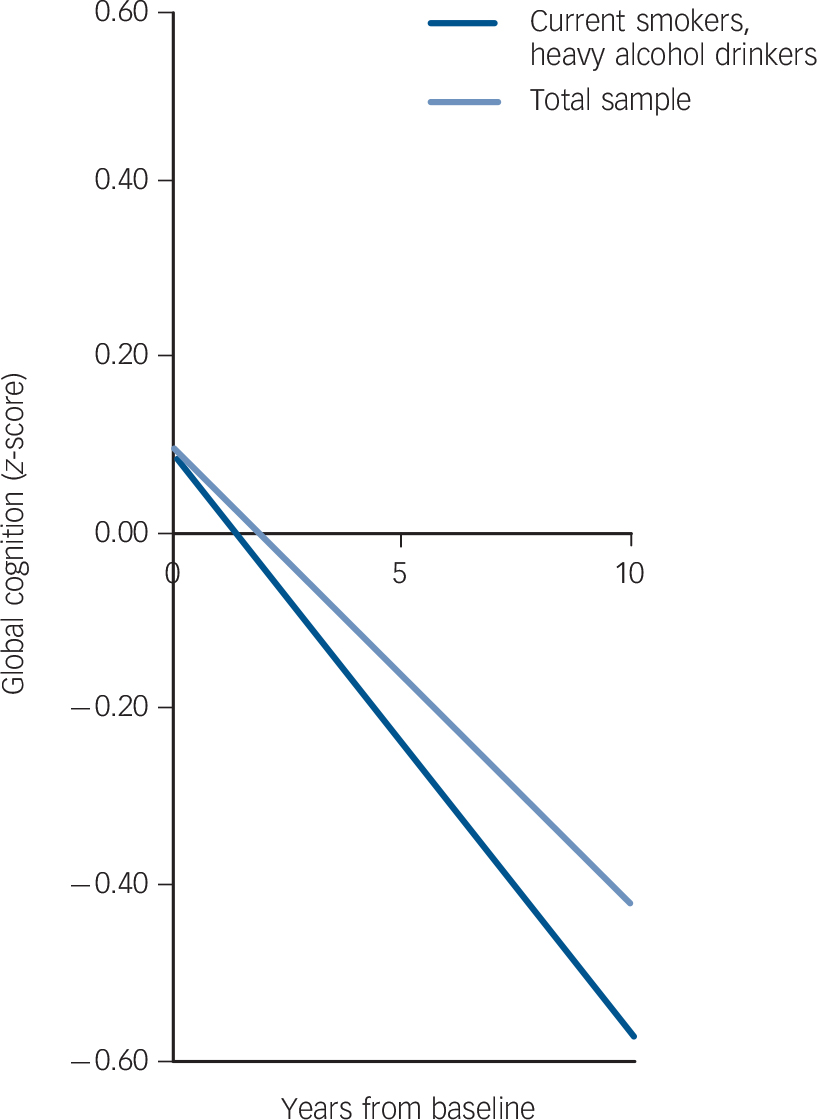

In analysis of cognitive decline (expressed as the change in cognitive function over 10 years), only one group differed significantly from the reference group of never smokers and moderate alcohol users. In individuals who were current smokers and who were also heavy drinkers, cognitive decline was 36% faster than the reference group. Cognitive decline in this group was equivalent to an age effect of 12 years (–0.153/–0.013 = 12), 2 years faster than in those who were non-smoking moderate drinkers (an age effect of 2 extra years over 10-year follow-up). Figure 1 shows both the baseline cognitive function (intercept) and the cognitive decline trajectory (slope) for the ‘current smoker, heavy drinker’ group compared with the total sample.

Table 1 Characteristics of the study population according to cigarette smoking status and alcohol drinking level (1997/99)

| Never smoker group (n = 3192) |

Ex-smoker group (n = 2647) |

Current smoker group (n = 634) |

P Footnote a | Total (n = 6473) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline, years: mean (s.d.) | 55.48 (6.09) | 56.25 (5.96) | 55.07 (5.75) | 0.17 | 55.76 (6.02) |

| Male, n (%)Footnote b | 2186 (68.5) | 2033 (76.8) | 416 (65.6) | 0.01 | 4635 (71.6) |

| Chronic disease, n (%)Footnote b | 672 (21.1) | 597 (22.6) | 153 (24.1) | 0.05 | 1422 (22.0) |

| Education, n (%)Footnote b | |||||

| Lower secondary or lower | 1272 (39.9) | 1239 (46.8) | 365 (57.6) | 2876 (44.4) | |

| Higher secondary | 812 (25.4) | 697 (26.3) | 165 (26.0) | <0.001 | 1674 (25.9) |

| University or higher | 1108 (34.7) | 711 (26.9) | 104 (16.4) | 1923 (29.7) | |

| Alcohol drinking status, units per week: n (%)Footnote b | |||||

| 0 | 597 (18.7) | 283 (10.7) | 114 (18.0) | 994 (15.4) | |

| 1-14 for women and 1-21 for men | 2033 (63.7) | 1567 (59.2) | 311 (49.1) | <0.001 | 3911 (60.4) |

| >14 for women and >21 for men | 562 (17.6) | 797 (30.1) | 209 (33.0) | 1568 (24.2) |

a. P-value for linear trend from never to current smoker (Mantel-Haenszel test for categorical variables).

b. % shows the column percentages within each smoking group and in the total sample.

Among those reporting alcohol consumption, we observed a linear dose-response association between log alcohol units and 10-year cognitive decline among the male smokers group (Bslope = −0.12, 95% CI −0.20 to −0.04, P = 0.004). Cognitive decline was faster as the number of alcohol units increased (online Fig. DS1).

Among males who were heavy alcohol drinkers, cigarette smoking (v. never smoking) was associated with significantly faster cognitive decline (Bslope = −0.22, 95% CI −0.35 to −0.10, P = 0.001), consistent with the results from the interaction models. Among these men there was little evidence for a dose-response association between the number of cigarettes smoked and cognitive decline: 1-10 cigarettes per day (Bslope = −0.14, 95% CI −0.28 to 0.01, P= 0.06); 11-20 cigarettes per day (Bslope = −0.32, 95% CI −0.53 to −0.10, P= 0.01); ⩾21 cigarettes per day (Bslope = −0.15, 95% CI −0.37 to 0.08, P= 0.21) (online Fig. DS2).

Fig. 1 Cognitive decline in the ‘current smoker, heavy alcohol drinker’ group compared with the total sample.

Table 2 Estimated meanFootnote a baseline cognitive function (intercept) and mean cognitive decline (slope) in the total sample and each of nine alcohol smoking status groups

| Cognitive function at baseline (intercepts), mean (95% CI) | Cognitive change over 10 years (slopes), mean (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample |

Never smoker |

Ex-smoker | Current smoker |

Total sample |

Never smoker |

Ex-smoker | Current smoker |

|

| Total sample (n = 6473) | 0.10 (0.07 to 0.12) | –0.42 (–0.44 to −0.40) | ||||||

| Alcohol units per week | ||||||||

| 0 (past 7 days) | –0.37 (–0.46 to −0.28)Footnote ** | –0.16 (–0.28 to −0.05)Footnote ** | –0.16 (–0.35 to 0.04)Footnote * | –0.40 (–0.46 to −0.34) | –0.38 (–0.46 to −0.30) | –0.50 (–0.65 to −0.35) | ||

| 1-14 for women and 1-21 for men (moderate drinker) | 0.10 (0.06 to 0.14)(reference) | 0.13 (0.09 to 0.18) | –0.16 (–0.27 to −0.05)Footnote ** | –0.42 (–0.45 to −0.39) (reference) | –0.42 (–0.45 to −0.38) | –0.37 (–0.44 to −0.29) | ||

| >14 for women and >21 for men (heavy drinker) | 0.19 (0.11 to 0.26)Footnote * | 0.28 (0.22 to 0.34)Footnote ** | 0.09 (–0.03 to 0.21) | –0.42 (–0.47 to −0.37) | –0.45 (–0.49 to −0.41) | –0.57 (–0.67 to −0.48)Footnote b Footnote ** | ||

a. Estimated means are adjusted for age, gender, education and chronic disease; intercept centred at age 55, male, with no chronic disease and having higher secondary level education.

b. 36% faster: 100×[(0.57 - 0.42)/0.42].

* P<0.05

** P<0.01: P-values are for comparison with the reference group (never smoker, moderate drinker).

Results from sensitivity analyses are summarised in Table 3 These did not influence the conclusions drawn from the main analysis materially. For the ‘non-smoker, 0 alcohol units per week’ group, effect sizes were similar for non-drinkers and occasional drinkers (17% v. 19% faster than the reference group respectively).

Discussion

This study of over 6000 adults aged 45-69 years at the start of cognitive testing examined cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption as predictors of cognitive decline assessed three times over 10 years. The combined effect of cigarette smoking and heavy alcohol consumption accelerated cognitive decline over the 10-year follow-up period. Cognitive decline was 36% faster in those who reported both cigarette smoking and drinking alcohol above the recommended limits at baseline, this effect was equivalent to an age effect of an additional 2 years over 10-year follow-up. The pattern was strongest for tests requiring executive function; that is reasoning, semantic and phonemic fluency.

Strengths and limitations

The large sample size, long follow-up period and multiple waves of cognitive assessment strengthen confidence in the results. Several known confounding factors were controlled for in the analysis. Combining four tests into a single measure of global cognition can reduce measurement error. There are some limitations to our study. First, participants reporting 0 alcohol units per week in the past 7 days were a heterogeneous group comprising occasional drinkers, lifetime abstainers, those with existing morbidity (including ‘sick quitters’) and those not drinking alcohol for other reasons. ‘Sick quitters’ may account partly for the significantly higher levels of chronic disease observed in those reporting 0 alcohol units per week (online Table DS3). It is also possible that symptoms of prodromal cognitive decline may have motivated participants to stop drinking alcohol. This makes it difficult to determine any protective effect of non-drinking, because this group contains some previously heavy drinkers and a high prevalence of chronic disease. However, effect sizes were similar among occasional and non-drinkers. Second, because all participants were white collar workers, results may not generalise to manual occupations or to the unemployed. However, the cohort covers a wide socioeconomic range, with a tenfold difference in full-time salary between the highest and lowest occupational grade.

Comparison to other studies

Previous studies evaluating the combined impact of cigarette smoking and alcohol use on risk of cognitive decline or dementia have focused on older adults, Reference Steffens, Otey, Alexopoulos, Butters, Cuthbert and Ganguli2,Reference Ngandu, Helkala, Soininen, Winblad, Tuomilehto and Nissinen20,Reference Leibovici, Ritchie, Ledésert and Touchon21,Reference Corley, Jia, Brett, Gow, Starr and Kyle35,Reference Tyas36 often with smaller sample sizes and have tended to be cross-sectional Reference Ngandu, Helkala, Soininen, Winblad, Tuomilehto and Nissinen20 or case-control studies of Alzheimer's disease, Reference Garcia, Ramon-Bou and Porta12,Reference Leibovici, Ritchie, Ledésert and Touchon21,Reference Tyas, Koval and Pederson22 few of which have been longitudinal. Reference Leibovici, Ritchie, Ledésert and Touchon21,Reference Tyas, Koval and Pederson22 Previous studies have also suggested that tobacco and alcohol may modify each other's effects on Alzheimer's disease, Reference Garcia, Ramon-Bou and Porta12,Reference Tyas, Koval and Pederson22 although these studies did not distinguish moderate from heavy alcohol drinkers. We studied longitudinally the combined effect of both behaviours from midlife to early old age on both cognitive function and decline.

Table 3 Summary of sensitivity analyses for the combined effect of heavy alcohol and current smoking v. moderate alcohol use and never smoking

| Issue | Procedure | Results | EffectFootnote

a

% |

Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possible cognitive impairment | Repeat model on those with MMSE score of 24 or more in 2002/04 and 2007/09 | Unchanged | 36 | Removal of cognitive impairment cases does not influence the results |

| Reverse causation (prior cognitive function may have led to heavy alcohol use at baseline) | Additionally adjust for vocabulary score | Association between heavy alcohol use and cognitive function at baseline attenuated by 40%. Cognitive decline slightly faster | 41 | Reverse causation may contribute to the association between heavy alcohol use and cognitive function at baseline, but does not contribute to the combined effect of heavy alcohol use and smoking on cognitive decline |

| Cumulated risk | Repeat using cumulative risk score from recruitment to baseline (1985/88, 1991/93, 1997/99) | Cumulated combined risk score associated with faster cognitive decline | N/AFootnote b | Cumulative combined exposure increases cognitive decline |

| Behaviour change during follow-up | Exclude current smokers who stopped smoking and heavy alcohol drinkers who reduced consumption | Cognitive decline slightly faster in combined heavy drinker, current smoker group | 37 | Combined effect is slightly stronger for participants who continue engaging in both behaviours over follow-up |

| Outliers | Exclude heavy smokers (>20 cigarettes per day) and very heavy drinkers (>35 units per week) | Cognitive decline only slightly attenuated in combined heavy drinker, current smoker group and still significant | 34 | These participants do not account for the interaction |

| Male smoker effect | Add interaction between gender and smoking status | Interaction term not attenuated and remains significant | N/AFootnote b | Male smokers do not account for the interaction |

| Specificity of effects | Repeat models on executive function/memory separately | Similar effect size for executive function, smaller and non-significant effect for memory | 39/19 | The interaction is apparently specific to executive function |

| Healthy survivor effects during follow-up | Repeat results on nested sample of participants with complete data during follow-up | Cognitive decline slightly faster in the combined heavy drinker, current smoker group | 42 | The combined effect of current smoking and heavy alcohol drinking on decline may be underestimated, as a result of healthy survivor effects from baseline to end of follow-up |

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; N/A, not applicable.

a. Effect represents the 100 ([decline in the ‘current smoker, heavy alcohol drinker’ group - decline in the ‘never smoker, moderate alcohol drinker’ group]/decline in the ‘never smoker, moderate alcohol drinker’ group).

b. These models are not comparable with others shown in the table because the exposures were parameterised as interaction terms rather than groups.

There is now consistent evidence to suggest that studies based on elderly people have selection bias because of the greater mortality among smokers, producing a selected group of older smokers. Reference Sabia, Marmot, Dufouil and Singh-Manoux37 Although our study followed participants from midlife, we found some evidence for a healthy survivor effect over follow-up. It is therefore likely that we underestimated the combined effect of smoking and heavy alcohol drinking on cognitive decline, owing to greater mortality among smokers and heavy alcohol drinkers. The findings presented here extend our previous report that smoking in men is associated with faster cognitive decline over 10 years (online Table DS4). Reference Sabia, Elbaz, Dugravot, Head, Shipley and Hagger-Johnson9

Meaning of the study

It is important to know whether the effects of smoking and alcohol use combine to increase risk of cognitive decline in early old age, since this may offer opportunities for prevention. Strategies designed to encourage adults to stop smoking could be implemented sequentially with other behaviour change interventions, such as using smoking cessation to begin discussions about other risky behaviours. Preventable risk factors that co-occur could potentially offer a double dividend, since removal of either risk factor can remove the excess risk associated with the risk factor and the excess risk associated with the interaction. Reference Kirkwood and Sterne34 However, the particularly strong combined effect we demonstrate here should not detract from concerns about the separate impact of unhealthy behaviours, Reference Anstey, von Sanden, Salim and O'Kearney8,Reference Anstey, Mack and Cherbuin13 particularly smoking, Reference Sabia, Elbaz, Dugravot, Head, Shipley and Hagger-Johnson9 but additionally shows the importance of looking at how the effects of behaviours may combine.

Future research should identify reasons why combining these two behaviours accelerates cognitive decline. Studies could look at cumulative damage to aerodigestive or vascular pathways and any subsequent association with cognitive decline. In terms of public health recommendations, guidelines already exist about smoking and drinking alcohol within recommended levels 26 but these could be modified to emphasise excess risk from combined behaviours.

Implications

From a public health perspective, the increasing burden associated with cognitive ageing could be reduced if lifestyle risk factors can be modified. Reference Anstey, von Sanden, Salim and O'Kearney8 We concur with Anttila et al Reference Anttila, Helkala, Viitanen, Ingemar, Fratiglioni and Winblad38 that people should not drink more heavily in the belief that alcohol is a protective factor against cognitive decline. Our findings, assuming the observed associations are causal, show that alcohol use and cigarette smoking do not appear to ‘cancel each other out’. Reference Tyas, Koval and Pederson22 Their combined effect appears to accelerate cognitive decline. Individuals who smoke should stop or cut down, and avoid heavy alcohol drinking, consistent with existing advice. Adults should additionally be advised however, not to combine these two unhealthy behaviours, particularly from midlife onwards.

Funding

G.H.-J. is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, NIH (R01AG034454, principal investigators: A.S-M. and M.K.) and from the NHS Leeds Flexibility & Sustainability Fund (principal investigator: Fullard). S.S is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, NIH (R01AG034454, principal investigator: A.S-M. and M.K.). A.S.-M. is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, NIH (R01AG013196; R01AG034454). M.S. is supported by the British Heart Foundation. M.K. is supported by the Medical Research Council, the National Institutes of Health (R01HL036310; R01AG034454), the Academy of Finland, and by a professorial fellowship from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). The Whitehall II study is also supported by a grant from the British Medical Research Council (K013351) and the British Heart Foundation. Tracing of stroke events was funded by a grant from the Stroke Association (principal investigator: E.J.B).

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the participating civil service departments and their welfare, personnel, and establishment officers; the British Occupational Health and Safety Agency; the British Council of Civil Service Unions; all participating civil servants in the Whitehall II study; and all members of the Whitehall II study team. The Whitehall II study team comprises research scientists, statisticians, study coordinators, nurses, data managers, administrative assistants and data entry staff, who make the study possible.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.