National guidelines from several countries are agreed that the medical care of patients with mental disorders is of paramount importance. Reference Unützer, Schoenbaum, Druss and Katon1–Reference Ruiz, Garcia, Ruiloba, Giner Ubago and Garc$lAa-Portilla González5 Yet, serious concerns have been raised about the quality of medical (and screening) services offered to patients with severe mental illness. Reference Mitchell, Malone and Carney Doebbeling6 Individuals with schizophrenia receive as little as half of the monitoring offered to people without schizophrenia in some studies. Reference Roberts, Roalfe, Wilson and Lester7 Further, there is evidence that people with severe mental illness receive suboptimal treatment for established medical conditions. Reference Vahia, Diwan, Bankole, Kehn, Nurhussein and Ramirez8,Reference Desai, Rosenheck, Druss and Perlin9 These disparities in treatment exist in some of the most critical areas of patient care such as general medicine, cardiovascular and cancer care. Reference Mateen, Jatoi, Lineberry, Aranguren, Creagan and Croghan10 This is particularly concerning given that people with schizophrenia appear to have higher rates of post-operative complications, Reference Li, Glance, Cai and Mukamel11 higher post-operative mortality Reference Copeland, Zeber, Pugh, Mortensen, Restrepo and Lawrence12 and higher than expected non-suicide-related mortality. Reference Saha, Chant and McGrath13 Indeed, the physical health of individuals with severe mental illness is poorer than the general population. Reference Prince, Patel, Saxena, Maj, Maselko and Phillips14,Reference Mitchell and Malone15 Looking at comorbidity in more detail shows that individuals with schizophrenia have higher rates of hypothyroidism, dermatitis, eczema, obesity, epilepsy, viral hepatitis, diabetes (type 2), essential hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and fluid/electrolyte disorders. Reference Carney, Jones and Woolson16,Reference Weber, Cowan, Millikan and Niebuhr17 Patients with bipolar I disorder also have higher rates of arthritis, hypertension, gastritis, angina and stomach ulcer. Reference Perron, Howard, Nienhuis, Bauer, Woodward and Kilbourne18 The presence of these medical comorbidities adversely affects not just quality of life but also recovery from the underlying psychiatric disorder, Reference Kisely and Simon19 length of hospital admissions Reference Zolnierek20 and paradoxically the likelihood of being offered psychotropic medication. Reference Chwastiak, Rosenheck and Leslie21

Patients with severe mental illness are also at risk of receiving less than adequate preventive services such as medical screening procedures. Medical screening is important not just for the reduction in future morbidity but also low receipt of preventive care is associated with lower quality of life. Reference Mackell, Harrison and McDonnell22 Lord et al recently reviewed studies that examined preventive care in individuals with v. without psychiatric illness. Reference Lord, Mitchell and Malone23 For those individuals with schizophrenia, eight of nine analyses showed inferior preventive care in several areas including in relation to osteoporosis screening, blood pressure monitoring, vaccinations, mammography and cholesterol monitoring. Reference Lord, Mitchell and Malone23 Although many of these chronic conditions may be unavoidable given our current state of knowledge, many deaths in those with mental illness appear to be avoidable. Reference Amaddeo, Barbui, Perini, Biggeri and Tansella24 Unfortunately, medical disorders are often overlooked by mental health specialists in psychiatric settings and by physicians in primary care and medical settings. As a result up to half of all chronic conditions may go unrecognised in severe mental illness. Reference Kilbourne, McCarthy, Welsh and Blow25–Reference Bernardo, Banegas, Canas, Casademot, Riesgo and Varela29 In addition, many people with mental ill health who have an unmet need for medical care also have other risk factors for poor treatment such as low income, social isolation, homelessness, substance misuse and lack of healthcare insurance. Reference Desai and Rosenheck30

Given these numerous concerns regarding quality of medical care, elevated mortality and low receipt of preventive services for people with a psychiatric disorder, we undertook a data synthesis of comparative studies that have examined the adequacy of medication prescribing for existing physical disorders in individuals with and without severe mental illness. To the best of our knowledge this is the first meta-analysis using prescribing data in mental ill health groups.

Method

Search and appraisal

A review strategy and extraction sheet was agreed according to the PRISMA standard. We decided to focus on non-organic psychiatric disorders, thus excluding studies pertaining to delirium or dementia. Reference Muther, Abholz, Wiese, Fuchs, Wollny and Pentzek31 We searched Medline/PubMed and Embase abstract databases from inception to November 2010. The initial search strategy is listed in the online supplement. We included any study (observational/interventional) that had measured the prescription or receipt of medication for medical conditions in patients with and without defined mental illness. Four full-text collections were searched: Science Direct, Ingenta Select, Springer-Verlag's LINK and Blackwell-Wiley. In these online databases the same search terms were used but as a full-text search and as a citation search. The abstract databases Web of Knowledge and Scopus were searched, using the terms in the online supplement as a text-word search, and using key papers in a reverse citation search. Finally, a number of journals were hand-searched (British Journal of Psychiatry, Schizophrenia Research, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Psychological Medicine, Acta Psychiatrica Scandavica, American Journal of Psychiatry, Archives of General Psychiatry, Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, Journal of Psychiatric Research, Psychiatric Services, The Psychiatrist (previously known as Psychiatric Bulletin); all from 2000) and several experts contacted. Using this strategy we identified 84 primary data publications and of these 61 reported aspects of quality of medical care other than prescribed medication. Several were excluded due to lack of extractable data despite attempts to find data from the original authors. Reference Cook, Grey, Burke-Miller, Cohen and Anastos32 Data were extracted by two authors (O.L. and A.J.M.) and independently checked by a third (D.F.) (see online supplement). Appraisal of individual studies was performed and the Newcastle-Ottawa evaluation scale for observational studies was used. Reference Wells, Shea, O'Connell, Peterson, Welch, Losos and Tugwell33 In addition, we performed a PRISMA evaluation of our meta-analysis using a standard checklist of 27 items that ensure the quality of a systematic review or meta-analysis. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman34 The Newcastle-Ottawa evaluation scale is a specific set of nine items used to evaluate individual studies. All medication listed in each publication was fully extracted to avoid meta-analytic bias resulting in 61 drug-level analyses.

Meta-analysis

From the available data, we entered or calculated odds ratios (OR) and r values. We extracted data on the rate of prescribed medication is those with v. without mental illness. Relative risks (hazard ratios) were converted into odds ratios with reference to the reported control event rate, an adaption of a method described elsewhere. Reference Zhang and Yu35 We then used a summary meta-analysis, pooling odds ratios. We attempted to account for potential confounders but these were variably handled by primary studies. We therefore extracted and stratified results into adjusted and unadjusted analysis and specified types of adjustment. Confidence intervals were obtained from all studies or calculated from the data provided. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman36 Heterogeneity was reduced by stratifying by either type of mental illness or drug class or type of medical condition. Where heterogeneity (defined by >80% I 2) was high, random-effects meta-analysis was preferred otherwise fixed-effects meta-analysis was used. We applied a minimum data-set rule, namely we required a minimum of three independent studies to justify pooling by individual drug class, a convention advised by a number of statistical programs such as STATA. Statsdirect version 2.7.7 for Windows was used to pool studies using the DerSimonian-Laird method for random-effects meta-analysis. Potential study bias was examined using Kendall's tau and Egger bias statistics, Reference Peters, Sutton, Jones, Abrams and Rushton37 but no evidence of publication bias was detected (see online supplement). In order to offer a qualitative interpretation of quantitative data we defined the following grades of treatment adequacy a priori with reference to the comparator population rates: <80% ‘inadequate’; ⩾80% <90% ‘suboptimal’; ⩾90% <95% ‘inequitable’; and ⩾95% ‘adequate’.

Results

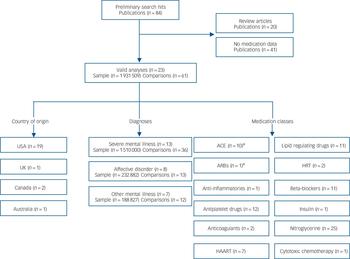

Our search identified 61 drug-level analyses regarding prescribing adequacy in 23 publications Reference Baxter, Samnaliev and Clark38–Reference Yun, Maravi, Kobayashi, Barton and Davidson60 involving 1 931 509 patients (study-level results shown in online Table DS1; overview of search results shown in Fig. 1). Subgroups included 13 analyses (36 drug-level comparisons) in patients with severe mental illness, 8 analyses (13 comparisons) in patients with affective disorder and 7 analyses (12 comparisons) for other miscellaneous mental illness groups. We used British National Formulary (BNF) codes to classify medications (www.bnf.org). In total, there were 12 classes of medication in the analysis: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ACE inhibitors/ARBs, BNF 2.5.5.1 and 2.5.5.5.2), nitroglycerine (BNF 2.6.1), anti-inflammatory medication for arthritis (BNF 4.7.1), antiplatelet drugs (BNF 2.9), anticoagulants (BNF 2.8), beta-blockers (BNF 2.4), cytotoxic chemotherapy (BNF 8.1), insulin (BNF 6.1.1), highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART, BNF 5.3.1), lipid-regulating drugs (includes statin and non-statins, BNF 2.12) and medication for osteoporosis (largely hormone replacement therapy (HRT), BNF 6.4.1.1). Thus, most were for cardiovascular health indications. We evaluated the quality of studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa criteria (online Table DS2). Using these nine domains we rated 2 studies as having a low overall quality, 12 as having moderate overall quality and 9 with high overall quality but all were considered sufficient for analysis.

Severe mental illness (including schizophrenia)

There were 36 analyses of drug prescribing from a combined pool of over 1.5 million individuals (Fig. 2). The pooled odds ratio for equitable prescribing was 0.74 (95% CI 0.63–0.86) favouring non-mental ill health. I 2 was 97.2 suggesting high heterogeneity. Lower than expected receipt of medication was in evidence for ACE/ARBs (OR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.81–0.98, P = 0.02), beta-blockers (OR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.84–0.96, P = 0.001) and statins (OR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.39–0.94, P = 0.02) but not for anticholesterol drugs in general (statins and non-statins combined), or for anticoagulants (aspirin and non-aspirin combined). However, for non-aspirin anticoagulants alone (clopidogrel and ticlopidine) there was a significantly lower rate (OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.56–0.97, P = 0.02). Results were similar when stratified by schizophrenia alone. For schizophrenia alone the pooled odds ratio across all medication was 0.69 (95% CI 0.57–0.83, P<0.0001).

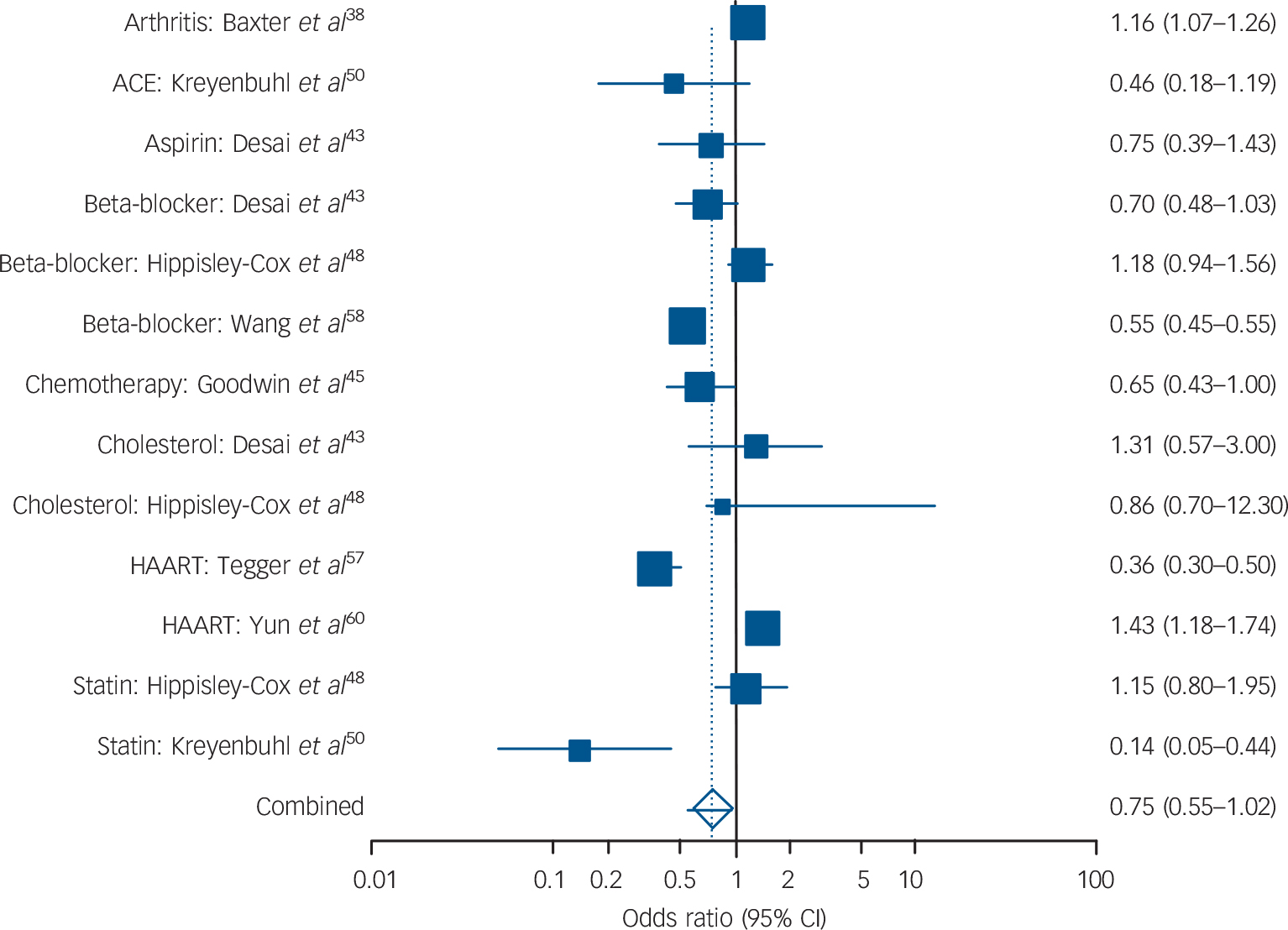

Affective disorder

Across 13 analyses involving 232 882 individuals the I 2 was 94.6%. The combined meta-analysis showed a trend towards low receipt with a pooled odds ratio of 0.75 (95% CI 0.55–1.02, P = 0.07), which was significant in fixed-effect but not random-effects analysis (Fig. 3). Lower receipt of medication was evident for beta-blockers (OR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.45–1.29) and lipid-regulating drugs (OR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.64–1.32), but neither were statistically significant. There was inadequate data to examine other classes of medication.

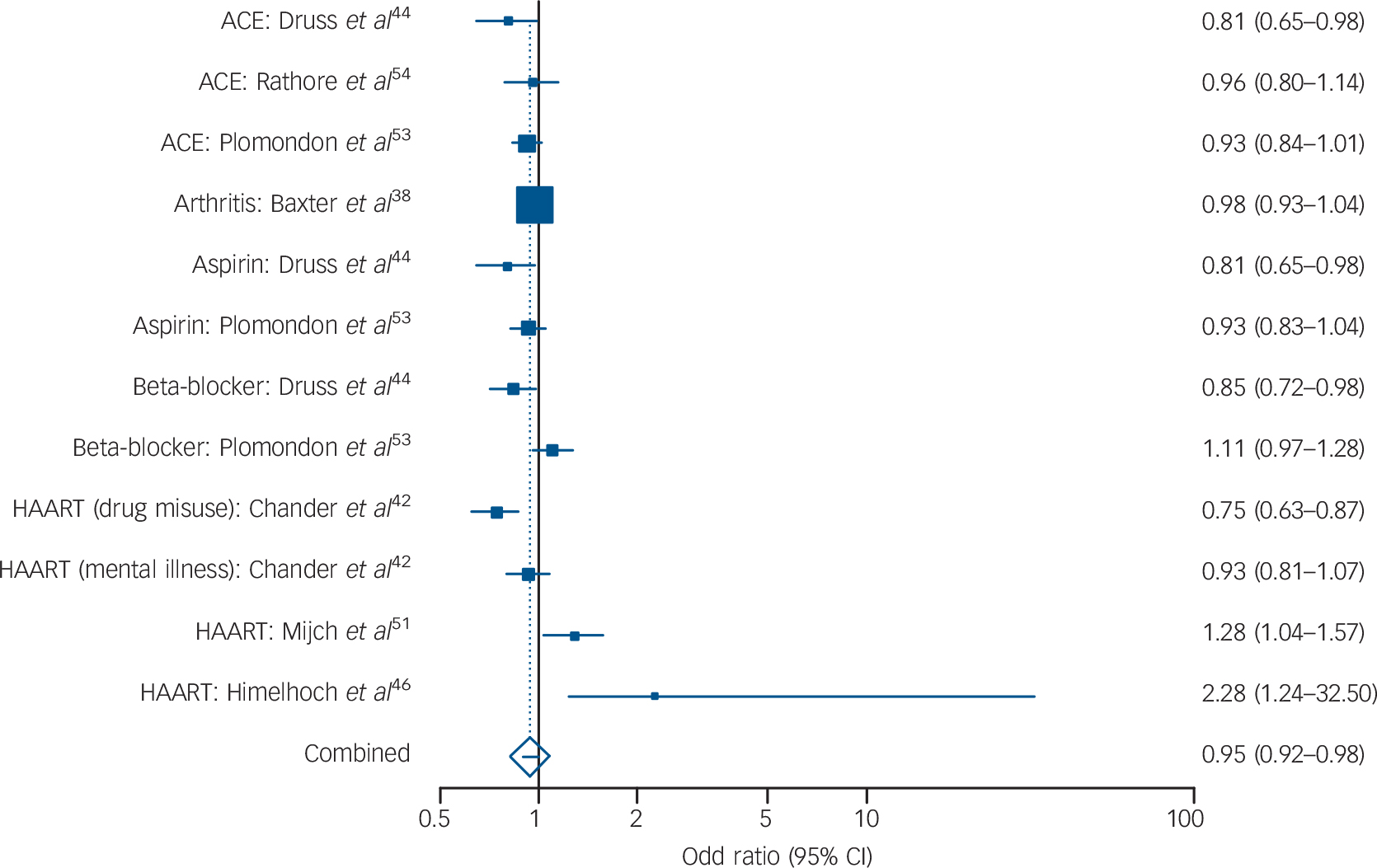

Other mental illness

Across 12 analyses (involving 19 637 individuals with mental illness from a sample of 188 627) the I 2 was 64.5%, suggesting low heterogeneity and permitting fixed-effects analysis. The combined pooled odds ratio was 0.95 (95% CI 0.92–0.98, Fig. 4). Lower receipt of medication was evident for ACE or ARBs (OR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–0.99) but not HAART medication (OR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.75–1.28). There was inadequate data to examine other classes of medication.

FIG. 1 Quorom overview of search results.

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy. a. Classes usually combined by convention.

A summary of results is shown in Table 1.

Discussion

Main findings

We found 61 comparative analyses relating to the prescription of 12 classes of medication including lipid-regulating agents (includes statins), beta-blockers, antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs, ACE/ARBs, insulin, cytotoxic chemotherapy, anti-inflammatories, HRT for osteoporosis and HAART for HIV. Patients with severe mental illness had an odds ratio of 0.74 (95% CI 0.63–0.86) for a comparable medication prescription. The differences were found largely in drugs for cardiovascular indications. For example, patients with severe mental illness received lower than expected prescriptions for ACE/ARBs, beta-blockers and statins. Combining all types of mental illness and all classes of drug suggested that patients with any type of mental illness had an odds ratio of 0.78 (95% CI 0.73–0.84, P = 0.0001) of comparable medication (data not shown). Given a typical control event rate (i.e. receipt of medication in the comparison group) of 70%, the actual rate of undertreatment can be estimated at 8% (95% CI 5–12) in those with other mental illness, 10% in those with severe mental illness and 12% in schizophrenia, a disparity that could be classified as ‘inequitable’ or ‘suboptimal’ receipt of medication according to our a priori definition.

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, we had no a priori protocol for this study but attempted to follow the review strategy suggested in the PRISMA standard. Heterogeneity was found in 5 out of 11 main analyses (Table 1) and this had the effect of rendering the odds ratios observed for affective disorders non-significant. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, which is only one of several possible methods. Reference Stang61 In two studies involving HAART there was no adjustment made for demographic, illness or prescribing variables Reference Mijch, Burgess, Judd, Grech, Komiti and Hoy51,Reference Yun, Maravi, Kobayashi, Barton and Davidson60 (see Table DS1) and therefore these data should be interpreted with caution. Without adjustment it is possible that the group with mental illness had more severe physical illness than the comparison group – although this should of course favour higher rates of prescribing, not lower rates. One study reported hazard ratios with no control event rate, Reference Himelhoch, Moore, Treisman and Gebo46 therefore we estimated the control event rate using data from related publications from the same group (pending confirmation from the authors). Another limitation is that the definition of mental illness, particularly severe mental illness varied considerably between studies, with seven studies defining mental illness using routine clinical interviews and one using prescription of haloperidol as a marker of mental ill health. The remaining studies used ICD-9 coding. A further important limitation is that most studies specified only that the mental health diagnosis was present in the year preceding the prescription of medication and therefore concurrent mental illness, symptoms of mental illness and severity of mental illness cannot be adequately reported. We also note that although the majority of disparities were manifest in drugs prescribed for cardiovascular conditions, the sample size was modest for most other medical conditions. We also note that in all but 1 of the 23 studies the setting was a country where health insurance is operating (largely USA), as opposed to socialised healthcare. Further studies should examine potential prescribing inequalities in countries with nationalised healthcare. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, all but two studies (see overleaf) measured prescribing from electronic databases based on naturalistic observational data and thus no information was available on patient v. prescriber influences on low receipt of necessary medication.

FIG. 2 Prescribing differences for severe mental illness v. no mental illness: summary meta-analysis plot (random effects).

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; IHD, ischaemic heart disease.

FIG. 3 Prescribing differences for affective disorder v. no mental illness: summary meta-analysis plot (random effects).

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

FIG. 4 Prescribing differences for other mental illnessa v. no mental illness: summary meta-analysis plot (fixed effects).

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

a. Other mental illness includes any type of mental ill health other than pure affective disorder, severe mental illness or schizophrenia.

Possible explanations for suboptimal prescribing

It is already widely known that people with mental ill health have problems with psychotropic medication adherence. Reference Mitchell62,Reference Mitchell and Selmes63 This also applies to adherence to physical health medications. Reference DiMatteo, Lepper and Croghan64–Reference Katon, Russo, Lin, Heckbert, Karter and Williams66 However, the studies reviewed here measure medication prescribing according to notations in medication databases (with the exception of Bishop et al who used notations in medical notes Reference Bishop, Alexander, Lund and Klepser39 and Suvisaari et al who used patient-reported medication at interview Reference Suvisaari, Jonna Perälä, Saarni, Kattainen, Lönnqvist and Reunanen56 ). Thus, uptake of medication and adherence to medication was not measured. We suggest therefore that the amount of medication actually taken as directed was probably less than that recorded here, and actual disparities in medication consumption may be more severe than disparities in prescribing. That said, some studies have found no difference or higher medication adherence to psychotropic drugs compared with physical health medication. Reference Piette, Heisler, Ganoczy, McCarthy and Valenstein67,Reference Himelhoch, Brown, Walkup, Chander, Korthius and Afful68 It may be important to acknowledge that insurance coverage influences uptake of medication in the USA and Canada. Reference Mulvale and Hurley69 However, the studies here do not measure uptake but rather prescribing. As many people with mental illness are unaware of their formal medical diagnosis and uninformed about their physical health medication, Reference Suvisaari, Jonna Perälä, Saarni, Kattainen, Lönnqvist and Reunanen56 we suggestthatthe disparitiesnoted are more likely to relate to physician habits than patient preferences.

TABLE 1 Overview of meta-analytic resultsFootnote a

| Severe mental illness/schizophrenia | Affective disorder | Other mental illnessFootnote b | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | Z | P | I 2, % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Z | P | I 2, % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Z | P | I 2, % (95% CI) | |

| All classes | 0.74 (0.63–0.86) | –3.83 | 0.001 | 97.2 (96.9–97.5) | 0.75 (0.55–1.02) | –1.82 | 0.07 | 94.6 (92.9–95.8) | 0.95 (0.92–0.98) | –3.07 | 0.002 | 64.5 (21.4–79.3) |

| ACEs or ARBs | 0.89 (0.81–0.98) | –2.31 | 0.021 | 74 (18.6–86.8) | Insufficient data | 0.92 (0.85–0.99)Footnote c | –2.27 | 0.02 | 0 (0–72.9) | |||

| Anticoagulant (including aspirin) | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | –0.67 | 0.500 | 3.4 (0–57.8) | Insufficient data | Insufficient data | ||||||

| Beta-blockers | 0.90 (0.84–0.96) | –3.2 | 0.001 | 63.1 (0–81.8) | 0.76 (0.45–1.29) | –1.01 | 0.3134 | 93.5 (83.7–96.3) | Insufficient data | |||

| Anticholesterol drugs | 0.59 (0.33–1.06) | –1.75 | 0.08Footnote d | 98.7 (98.4–98.9) | 0.92 (0.64–1.32) | –0.46 | 0.6469 | 77.2 (0–89.7) | Insufficient data | |||

| HIV HAART medication | Insufficient data | Insufficient data | 0.98 (0.75–1.28) | –0.164 | 0.8693 | 82.6 (36–91.5) | ||||||

ACEs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

a. Analysis: Z-test: test that odds ratio differs from 1; I 2, inconsistency: <80% equals low >80% equals high.

b. Other mental illness includes any type of mental ill health other than pure affective disorder, severe mental illness or schizophrenia.

c. Fixed-effects odds ratio.

d. Significant for statins alone.

Where physical health medication is prescribed by mental health professionals several factors may influence underprescribing. Previous work has shown that mental health professionals often miss physical conditions in their patients Reference Koranyi26,Reference Felker, Yazell and Short70,Reference Koran, Sox, Marton, Moltzen, Sox and Kraemer71 and undertake physical examinations in less than 50% of their patients. Reference Bobes, Alegría, Saiz-Gonzalez, Barber, Pérez and Saiz-Ruiz72 Mental health professionals often do not feel confident in prescribing physical health medication. Yet in the majority of cases physical health medication is prescribed by physicians in primary care, internal medicine and related medical specialties. We already know that mental health status and prescription of antipsychotics reduces likelihood of medical monitoring (such as glycated haemoglobin (HBA1c) testing). Reference Mitchell, Malone and Carney Doebbeling6,Reference Banta, Morrato, Lee and Haviland73 Primary care physicians often consider such patients to be ‘difficult to manage’, although many primary care physicians are willing to help with physical healthcare. Reference Lester, Tritter and Sorohan74,Reference Oud, Schuling, Slooff, Groenier, Dekker and Meyboom-de Jong75 Where primary care physicians lack expertise in mental health they are less likely to offer general care to those with mental illness. Reference Fleury, Bamvita and Tremblay76 Similarly when people with mental illness attend emergency departments they are less likely to be offered hospital care than other people. Reference Sullivan, Han, Moore and Kotrla77 In general practice, cardiovascular risk factors are often recorded in the medical records for adults with long-term mental illness, but primary care physicians appear reluctant to intervene. Reference Kendrick78 Clinician factors such as willingness to investigate, ability and enthusiasm to treat and willingness to offer follow-up are important predictors of quality of care. Because of medical and psychiatric comorbidity, seemingly unrelated conditions compete for clinicians’ attention. Reference Piette and Kerr79 Against this, studies suggest that the adequacy of medical care may not be adversely influenced by the number of comorbid medical disorders. Reference Min, Wenger, Fung, Chang, Ganz and Higashi80,Reference Higashi, Wenger, Adams, Fung, Roland and McGlynn81 Indeed, some have found that comorbidity favours superior care by virtue of higher than average healthcare visits. Reference Kurdyak and Gnam82 Indirect evidence suggests that clinicians’ attitudes towards patients directly influence health outcomes. In one study in primary care, poor mental health status was linked with poor accessibility, poorer general practitioner attitude and less time spent with the general practitioner. Reference Al-Mandhari, Hassan and Haran83 In a study of 59 patients seen in a US community mental health centre, 14% reported that they used the medical emergency department for their routine medical care needs and 45% said that their mental health provider did not ask them about medical issues. Reference Levinson Miller, Druss, Dombrowski and Rosenheck84

Three mitigating factors might explain low physician prescribing of physical health medication namely cautious prescribing, deferred prescribing and low patient acceptance of suggested medication. Regarding intentionally cautious prescribing, physicians’ prescription of cardiovascular medication may be cautious in light of possible links with suicide. Reference Reith and Edmonds85 Most plausibly this could apply to cholesterol-lowering agents, Reference Muldoon, Manuck, Mendelsohn, Kaplan and Belle86,Reference Lester87 beta-blockers Reference Sorensen, Mellemkjaer and Olsen88 and angiotensin-receptor antagonists. Reference Callréus, Agerskov Andersen, Hallas and Andersen89 Less likely but theoretically possible, physicians might be cautious about using aspirin together with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors due to gastrointestinal bleeding, and ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers in people with mental illness who smoke. A second possibility is that treatment in some circumstances is deferred rather than omitted, although evidence suggests that in the context of mental illness most deferred treatment is not received at a later date. Reference Evon, Verma, Dougherty, Batey, Russo and Zacks90 A third hypothesis underlying inadequate prescriptions is low uptake of care on account of patient preference. It is not yet clear if this is the primary explanation. Reference Cradock-O'Leary, Young, Yano, Wang and Lee91–Reference Folsom, McCahill, Bartels, Lindamer, Ganiats and Jeste93 For example, Salsberry and colleagues (2005) found that compared with the general population, those with severe mental illness had more emergency department visits and visited a doctor more frequently, but despite this high healthcare utilisation had very low rates of cervical smears and mammograms. Reference Salsberry, Chipps and Kennedy94 People with mental ill health perceive barriers to accessing primary physical healthcare. Reference Levinson Miller, Druss, Dombrowski and Rosenheck84,Reference Dickerson, McNary, Brown, Kreyenbuhl, Goldberg and Dixon92,Reference Crews, Batal, Elasy, Casper and Mehler95–Reference Bradford, Kim, Braxton, Marx, Butterfield and Elbogen97 Patients often cite lack of availability of medical advice and poor quality of medical advice as influential. Reference Levinson Miller, Druss, Dombrowski and Rosenheck84,Reference Druss and Rosenheck98,Reference O'Day, Killeen, Sutton and Iezzoni99 Observational evidence shows many have difficulty getting timely access to appropriate primary healthcare. Reference Farmer27,Reference Bradford, Kim, Braxton, Marx, Butterfield and Elbogen97,Reference Rice and Duncan100,Reference Chwastiak, Rosenheck and Kazis101 For example, data from the 1999 Large Health Survey of Veterans found that veterans with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or a drug use disorder were less likely to have had any primary care visit than those without these diagnoses, even after controlling for medical comorbidity. Reference Chwastiak, Rosenheck and Kazis101

Intervention to improve therapeutic care

Assuming these disparities in prescribing are robust, what can be done to improve quality of medical care? Druss & von Esenwein (2006) Reference Druss and von Esenwein102 reviewed six randomised trials designed to improve medical care in psychiatric conditions. These studies demonstrated a substantial positive impact on linkage to and quality of medical care albeit with a diverse range of interventions. One study showed that a simple intervention could improve readiness to begin HAART. Reference Balfour, Kowal, Silverman, Tasca, Angel and Macpherson103 Ismail et al and Winkley et al pooled 46 trials regarding the effect of psychological treatment on glycaemic control but showed only very modest effects in adults. Reference Ismail, Winkley and Rabe-Hesketh104,Reference Winkley, Landau, Eisler and Ismail105 Anderson et al (1998) reported a meta-analysis of 43 studies involving strategies to improve the delivery of preventive care that could hold valuable lessons. Reference Anderson, Janes and Jenkins106 In general, interventions were moderately effective in improving immunisation, screening and counselling. Reference Anderson, Janes and Jenkins106 In this data-set, two studies examined the effect of antidepressant treatment on HAART utilisation in patients with depression. Tegger et al (2008) found that untreated patients were 40% as likely to receive HAART; in treated patients there was no significant difference. Reference Tegger, Crane, Tapia, Uldall, Holte and Kitahata57 Similarly, Cook et al found that mental health treatment increased the probability of self-reported HAART use. Reference Cook, Grey, Burke-Miller, Cohen and Anastos32 Primary care physician recommendation of screening has been shown to be one of the strongest predictors of receipts of screening. Reference Friedman, Neff, Webb and Latham107–Reference Friedman, Puryear, Moore and Green110 Better communication between primary care providers and specialist mental health services might improve prescribing for mental and physical ill health. Reference Oud, Schuling, Slooff, Groenier, Dekker and Meyboom-de Jong75,Reference Phelan, Stradins and Morrison111 However, in a trial of an integrated model of care for older people, the intervention helped with access but did not produce any significant treatment effects for depression or anxiety. Reference Arean, Ayalon, Jin, McCulloch, Linkins and Chen112

From a research perspective, a detailed examination of patient and provider influences on received medication is urgently needed. Clinically, we suggest that treatment of comorbid physical conditions is prioritised in patients with mental health concerns and closely monitored. Reference Dickinson, Dickinson, Rost, DeGruy, Emsermann and Froshaug113 Clinicians caring for patients with physical and mental illness should take particular care to ensure optimal treatment is maintained in both areas. At an organisation level, monitoring systems are needed to ensure that the medical care of people with mental ill health is not overlooked.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Ferguson for helping with the extraction of quality appraisal of primary studies.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.