Depression is the most common mental illness among older people, and is associated with increased morbidity, premature mortality and greater healthcare utilisation. Reference Alexopoulos1–Reference Katon, Lin, Russo and Un¨tzer3 Treatment of depression is inadequate for most older people, being complicated by poor recognition and an increased prevalence of medication side-effects, polypharmacy and poor adherence to treatment. Reference Birrer and Vemuri4–Reference Zivin and Kales6 Depression is predicted to become the leading cause of disease burden among older people by 2020, Reference Goodwin7 at which time one in five of the population will be aged over 60 years. 8 Effective treatment of depression in older people is a salient public health priority, for which exercise has been increasingly evaluated as a potential therapeutic strategy. Reference Barbour and Blumenthal9,Reference Trivedi, Greer, Grannemann, Chambliss and Jordan10 Findings from recent reviews, however, are difficult to interpret clinically, since they reflect qualitative syntheses of evidence from randomised and non-randomised trials, and trials in which pre-existing depression has not been an eligibility criterion. Reference Sjösten and Kivelä11,Reference Blake, Mo, Malik and Thomas12 There is uncertainty concerning the effect of exercise on depression among older people with clinically significant symptoms of depression. The aim of this study was to provide a clinically meaningful synthesis of evidence to support treatment decisions. The primary objective was to estimate the effect of exercise on depression severity among older people with clinically significant symptoms of depression. The secondary objective was to investigate any potential variation in treatment effect among pre-specified subgroups of the study stratified by depression eligibility criteria, specifically the selection of participants according to clinician-diagnosed depression or a symptom checklist threshold.

Method

Eligibility criteria

Studies were considered for inclusion if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of exercise interventions for depression among older people. A trial was accepted as a RCT if the allocation of participants to treatment and comparison groups was reported as randomised. Studies were considered for inclusion if the sample mean age was ⩾60 years. Setting the minimum age criterion at ⩾60 years is consistent with previous reviews Reference Sjösten and Kivelä11,Reference Blake, Mo, Malik and Thomas12 and the World Health Organization's classification of older age, 13 and linking age to the sample, rather than the individual, recognises that trials vary in the use and precise specification of the minimum age criterion. The review included studies in which participant eligibility required pre-existing depression determined by a clinically valid method of assessment, such as a clinical interview, clinician diagnosis or symptom checklist threshold. Trials of any exercise intervention compared with any concurrent control were eligible. Exercise was defined as any planned or structured movement of the body performed systematically in terms of frequency, intensity and duration. Included trials reported depression as an outcome assessed at follow-up of ⩾3 months.

Study identification

To identify relevant published, unpublished and ongoing trials, as well as existing systematic reviews, the following electronic databases were search from inception to January 2011: CDSR, DARE, UK-NRR, CCT, HSRProj, CENTRAL, Medline; Embase, PsycINFO, SSCI, SportsDiscus, AMED, CINAHL, BioMed Central, HealthPromis, Index of Conference Proceedings, Theses, SIGLE and GreyLit. Search parameters were adapted to database requirements, and combined exploded MeSH terms and text words related to exercise, depression and age (see online supplement). The bibliographies of all included studies and review articles were screened for further references. Search results were recorded to bibliographic software, and two reviewers independently screened each citation for potential relevance against eligibility criteria. For all potentially relevant citations, full-text papers were obtained and assessed against eligibility criteria by two reviewers independently, with disagreements resolved by discussion.

Data abstraction

Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked for accuracy by another, using a template that included: (a) design, for example depression eligibility criteria, sample size and recruitment context; (b) participants, for example age, gender and baseline depression; (c) intervention, for example type, frequency and format of exercise; (d) outcome, for example depression measure, follow-up schedule and depression severity (mean and standard deviation) for each group at each follow-up; and (e) process, for example number of eligible patients invited and, for the exercise group, adherence, including the criteria used and the level achieved.

Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias in each trial according to the adequacy of sequence generation, allocation concealment, masking of outcome assessors, completeness of follow-up and analysis by intention to treat. Each component was assessed as either adequate, inadequate or unclear, using Cochrane risk of bias criteria. Reference Higgins and Green14 Risk of bias in each study was classified as either low (all criteria graded adequate), moderate (one criterion graded inadequate, or two graded unclear) or high (two or more criteria graded inadequate, or more than two graded unclear).

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using Review Manager version 5.1 software for Windows. All trials reported depression as a continuous outcome, but different measurers were used in the assessment. Thus, the summary measure of treatment effect was the between-groups difference in mean severity of depression, expressed as a standardised mean difference (SMD) using Hedges’ (adjusted) g, which includes a correction term for sample size bias. Reference Hedges and Vevea15 Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by the I 2 test, which describes the percentage of variability among effect estimates beyond that expected by chance. Heterogeneity can be considered as unlikely to be important for I 2 values up to 40%. Reference Higgins and Green14 In the absence of statistical heterogeneity (I 2 = ⩽40%), individual effect sizes were combined statistically using the inverse variance random-effects method, which assumes that true effects are normally distributed. The random-effects model is more conservative than the fixed-effect model since, by incorporating both within- and between-study variance, confidence intervals for the summary effect are wider. Risk of small study bias was assessed by visual assessment of funnel symmetry in the plots of each trial's SMD against its standard error (s.e.). Reference Higgins and Green14

The effect of exercise on depression severity was estimated in pre-specified subgroups of the study stratified by depression eligibility criteria. Specifically, we distinguished between trials in which participant eligibility was dependent on either satisfying clinical diagnostic criteria for depression or achieving a threshold score on a depression symptom checklist. The robustness of results was assessed in separate sensitivity analyses that excluded trials with moderate or high risk of bias, non-active or no intervention control comparators and end-points within rather than beyond the intervention period.

Results

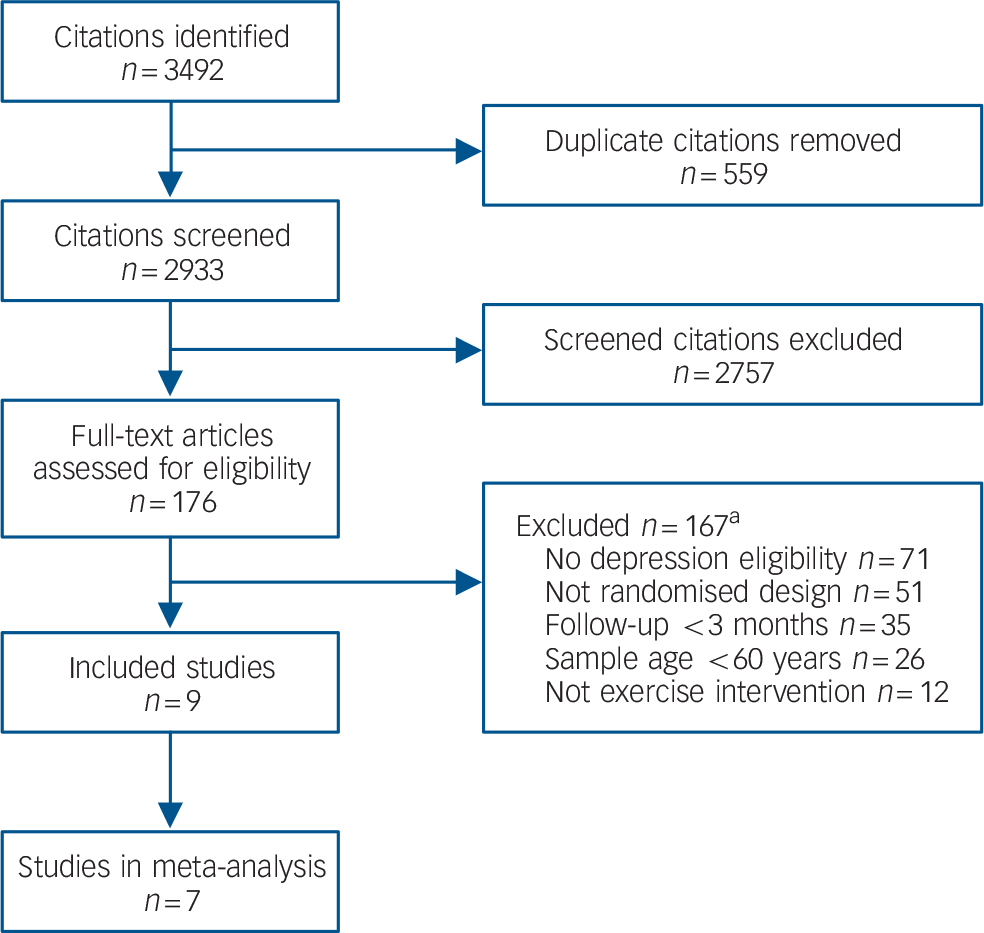

After removal of duplicates, the search strategy identified 2933 distinct citations, of which 2757 (94%) were excluded during the initial screening phase (Fig. 1). For the remaining 176 citations, full-text papers were ordered, obtained and independently assessed against the eligibility criteria, with five discrepancies resolved by discussion (97% agreement, k = 0.75). Nine studies met the inclusion criteria. Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16–Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 The main reasons for exclusion of full-text papers were use of non-randomised designs, primary end-points less than 3 months and depression not required for participant eligibility.

FIG 1 Flow diagram of study selection.

a. Some studies excluded for multiple reasons.

Characteristics of included studies

Of the nine included trials (Table 1), four were conducted in the USA, Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16–Reference Williams and Tappen19 and one each in the UK, Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 Australia, Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 New Zealand, Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 China Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23 and Hong Kong. Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 Three trials were explicitly identified in the study report as being either feasibility, Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 pilot Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16 or efficacy studies. Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18 The nine trials randomised 667 participants (69% female), with sample size ranging from 14 to 193. The mean age of trial populations ranged from 65 years Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 to over 80 years. Reference Williams and Tappen19,Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22,Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24

Depression eligibility was determined by clinician diagnosis, Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 symptom checklist, Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16,Reference Williams and Tappen19,Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21,Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23 either a diagnosis or symptom checklist, Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 or a three-question depression screen validated for use in primary care. Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 Baseline receipt of antidepressant medication was required for eligibility in one trial, Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 was an exclusion criterion in three Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16,Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 and allowed but not required in four. Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Williams and Tappen19,Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22,Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 Common exclusion criteria included medical conditions for which exercise was contraindicated, psychiatric illness, cognitive impairment, alcohol or substance misuse and, to a lesser extent, being a regular exerciser Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 or lacking motivation to exercise. Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21

In two trials the exercise intervention was classified as three-dimensional (3D) training, which included Tai Chi Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23 and Qi Gong. Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 The remaining seven trials included elements of endurance and strength training, and were classified as mixed exercise, including four trials described in the trial's report as mixed, two Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 that were based mostly on strength training but included elements of endurance training, and one Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17 in which endurance training was prescribed and strength training activities were encouraged. Interventions typically involved exercising for three to five, 30–45 min sessions per week for 3–4 months. Exercise was completed in participants’ homes, Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 including care homes, Reference Williams and Tappen19,Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 and various community-based facilities. Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16,Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20,Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21,Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23 Exercise was supervised in all but two trials Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 and completed in either group Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16,Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20,Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23,Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 or individual Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Williams and Tappen19,Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21,Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 formats.

TABLE 1 Characteristics of included studies

| Study, author

(country), depression eligibility |

Participants,

n (% female); age, years mean (s.d.); depression, mean (s.d.) |

Interventions,

exercise type, intensity, frequency and duration, programme length, setting and provider |

Outcome,

measure (end-point): mean (s.d.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brenes

Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16

(USA), PHQ-9 (2–4 symptoms) |

37 (62); 74.6 (6.6); GDS-15: I = 7.0 (3.0), C = 7.8 (4.2) |

I: Moderate-/high-intensity aerobic

and resistance training at three 60 min weekly group sessions for 4 months. Delivered by ACSM instructor in local sports centre. C: Telephone discussion with researcher about health status at 2, 6, 10 and 14 weeks |

GDS-15 (4 months): I = 4.5 (2.9), C = 6.3 (3.5) |

| Chiechanowski

Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17

(USA), DSM-IV minor depression or dysthemia |

138 (79); 73.0 (8.5);

HSCL-20: I = 1.3 (0.5), C = 1.2 (0.5) |

I: Depression management programme

of eight 50 min individual sessions over 19 weeks, promoting 30 min moderate intensity activity on 5 days per week. C: Physician informed of positive depression screen and advised usual care |

HSCL-20 (12 months): I = 0.82 (0.62), C = 1.01 (0.46) |

| Chou Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23 (China), CES-D ⩾16 | 14 (50); 72.6 (4.2); CES-D: I = 32.0 (9.9), C = 32.7 (8.7) |

I: Moderate-intensity Tai Chi at

three 45 min weekly group sessions for 3 months. Delivered by Tai Chi practitioner in a psychogeriatric out-patient clinic. C: No intervention, waiting list |

CES-D (3 months): I = 15.3 (9.8), C = 39.1 (9.7) |

| Kerse

Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22

(New Zealand), 3-question, primary care depression screen |

193 (58.5); 81.1 (4.4);

GDS-15: I = 3.4 (2.7), C = 4.0 (2.8) |

I: Otago programme –

moderate-intensity balance, progressive resistance and strengthening exercises and walking, each at three 30 min sessions per week for 6 months. Delivered at home by trained nurse in seven visits over 3 months. C: Equal social contact with nurse using conversational guide |

GDS-15 (12 months): I = 2.4 (2.2), C = 2.8 (2.2) |

| Mather

Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20

(UK), ICD-10 mood disorder + GDS ⩾10 + antidepressant |

86 (69); 64.9 (range 53–91); HRSD: I = 16.7, C = 17.4 |

I: Mixed endurance, strength and

stretching exercise at two 45 min group sessions per week for 10 weeks. C: Equal contact health education talks, including sessions on depression and exercise |

HRSD (34 weeks): I = 11.5 (3.3), C = 13.7 (3.3) |

| Sims Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 (Australia), GDS ⩾11 | 38 (66); 74.3 (5.9); GDS-30: I = 12.6 (3.6), C = 12.2 (3.5) |

I: Moderate-intensity progressive

resistance training at three 30 min weekly sessions for 10 weeks. Tailored and delivered by gym instructor in local gym. C: Exercise advice and information about local exercise options |

GDS-30 (6 months): I = 11.5 (6.7), C = 11.9 (4.9) |

| Singh

Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18

(USA), DSM-IV criteria for (unipolar) depression including dysthymia |

32 (63); 71 (2.0); BDI: I = 21.0 (2.0), C = 18.3 (1.8) |

I: High-intensity progressive

resistance training at three 45 min weekly group sessions for 10 weeks, supervised at university facility, followed by 10 weeks, unsupervised exercise at home with weekly telephone support. C: Health education lectures and videos at two 1 h group sessions per week for 10 weeks |

BDI (20 weeks): I = 9.2 (2.8), C = 11.0 (2.4) |

| Tsang

Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24

(Hong Kong), current diagnosis or GDS (cut-off NR) |

97 (81); 82.3 (NR); GDS-15: I = 5.17 (2.8), C = 6.50 (1.4) |

I: Moderate-intensity Qi Gong at

three 30–45 min weekly group sessions with 15 min/day unsupervised Qi Gong for 16 weeks. Delivered in care home by Qi Gong practitioner. C: Newspaper reading group with therapist in care home – equal contact |

GDS-15 (24 weeks): I = 3.4 (2.5), C = 5.7 (1.5) |

| Williams Reference Williams and Tappen19 (USA), CSDD ⩾7 | 32 (89); 87.9 (6.0); CSDD: I = 12.18 (5.0), C = 14.6 (5.8) |

All interventions delivered by

interventionists/researchers in care home at five 30 min individual weekly sessions for 16 weeks. I: Moderate-intensity mixed exercise – strength, balance, flexibility, walking. C: Social conversation |

CSDD (16 weeks): I = 9.7 (6.6), C = 11.8 (8.1) |

I, intervention group; C, control group; ACSM, American College of Sports Medicine; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HSCL-20, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-20; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CSDD: Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; NR, not reported.

Four trials compared exercise alone to an active usual care control, which included a referral letter sent to the primary care clinician recommending usual care, Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17 brief advice about exercise, Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 a structured health education programme Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 and telephone discussions of health status. Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16 A waiting-list control group (i.e. no contact intervention) was used in one trial, Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23 whereas in four trials exercise was compared with a non-active control intervention, for example equal contact or attentional control. Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Williams and Tappen19,Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22,Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 Outcomes were assessed at follow-up ranging from 3 to 12 months. In four trials the primary end-point (3–6 months) coincided with the end of the intervention period Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16,Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Williams and Tappen19,Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23 and in five it was 2–6 months post-intervention. In one study Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18 outcomes were assessed at 20 weeks and at 26 months, but only data from the former are synthesised so as to avoid introducing between-study variation in follow-up assessments.

In four trials Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20–Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 that reported the number of eligible patients invited to participate in the trial, the uptake, or recruitment rate, was 52% (38 of 73), Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 55% (193 of 353), Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 76% (86 of 113) Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 and 92% (138 of 150). Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17 Four trials Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20–Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 assessed adherence to the exercise intervention. In two trials, 75% (12/16) Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18 and 58% (11/19) Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 of participants satisfied the adherence criterion of attendance at ⩾20 of 30 exercise sessions. One trial Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 reported that the mean attendance at exercise sessions was 67%, which approximates to 13 of 20 exercise sessions. Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 In the final trial, Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 adherence was defined as completing ⩾2of3 prescribed exercise sessions per week as well as ⩾2 of 3 recommended walking sessions per week. At 6 months (1 month post-intervention), 64% of participants satisfied the criteria for adherence and, at 12 months (7 months post-intervention), 57% were adherent.

Risk of bias varied among the included studies (Appendix 1). Risk was assessed as high in two trials, Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23,Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 moderate in four Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16,Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Williams and Tappen19,Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 and low in three. Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20,Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 Across the nine trials a total of 27 (60%) risk of bias items were assessed as adequate, 11 (24%) were unclear and 7 (16%) were inadequate. Common methodological limitations included failure to analyse data according to the intention-to-treat principle, lack of masked outcome assessment and incomplete follow-up of participants. Risk of bias assessment was hindered by poor reporting practices, including both inconsistent and insufficient reporting.

Effect of exercise on depression

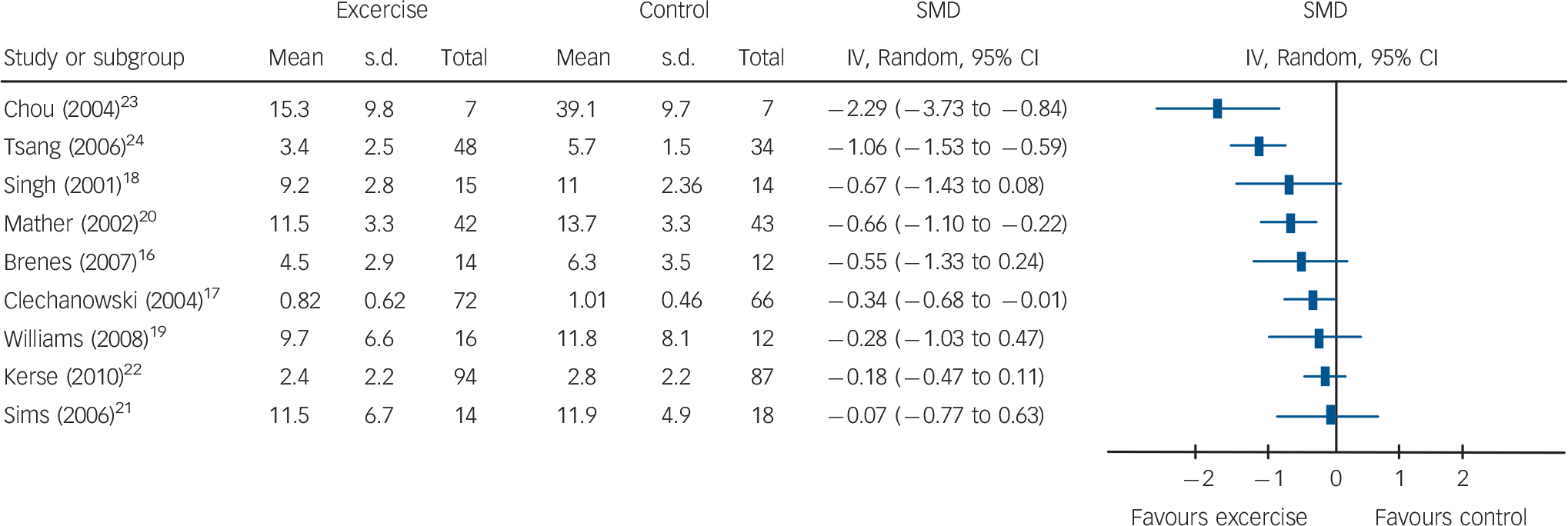

The point estimate of effect for each trial indicated lower depression severity among participants allocated to the exercise group compared with those allocated to the non-exercise control (Fig. 2). In four Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20,Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23,Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 of nine trials the difference in depression severity was statistically significant. Two trials Reference Chou, Lee, Yu, Yeung–Hung Chen, Chan and Chi23,Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 of 3D exercise reported effect sizes of far greater magnitude than the remaining trials, and statistical heterogeneity was detected among trial-level effects (I 2 = 58%, χ2 = 18.97, d.f. = 8, P = 0.02). The two trials were removed and neither contributed to subsequent analyses. The decision not to combine the trials in a separate synthesis was based on the detection of statistical heterogeneity between the trials (I 2 = 60%, χ2 = 2.48, d.f. = 1, P = 0.12) and assessment of each trial as having high risk of bias.

Only trials of mixed exercise contributed data to the pooled analyses (Table 2). The synthesis of data from seven trials produced a small but statistically significant effect in which exercise was associated with lower severity of depression (SMD = –0.34, 95% CI –0.52 to –0.17). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity among the pooled estimates (I Reference Blazer2 = 0%), and no indication of small study bias (Egger –0.52, 95% CI –3.72 to 2.69, P = 0.72).

Small, statistically significant effects emerged from the synthesis of three trials Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 in which participant eligibility required a current diagnosis of depression (SMD = –0.38, 95% CI –0.67 to –0.10), and in four trials Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16,Reference Williams and Tappen19,Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21,Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 using a symptom checklist threshold (SMD = –0.34, 95% CI –0.62 to –0.06). For the latter synthesis there was some indication of variation among the pooled estimates (I 2 = 25%), but this was unlikely to be important and did not exceed what would be expected by chance alone (χ2 = 4.02, d.f. = 3, P = 0.26).

Small, statistically significant effects favouring exercise were observed in three trials Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20,Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 with low risk of bias (SMD = –0.36, 95% CI –0.61 to –0.10), four trials Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20,Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 using an active intervention control (SMD = –0.44, 95% CI –0.67 to –0.20), and four trials Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17,Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20–Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 with extended follow-up (SMD = –0.32, 95% CI –0.54 to –0.10). Variation among pooled estimates was detected but did not exceed what would be expected by chance alone in the analyses for risk of bias (I 2 = 25%, χ2 = 3.20, d.f. = 2; P = 0.20) and follow-up period (I 2 = 19%, χ2 = 3.72; d.f. = 3, P = 0.29). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity among trials comparing exercise with an active usual care control (I Reference Blazer2 = 0%, χ2 = 2.43; d.f. = 3, P = 0.49).

FIG. 2 Trial-level data, effect estimates and forest plots for depression severity. SMD, standard mean difference.

TABLE 2 Summary results for pooled analyses

| Effect foci | Trials, n (participants, n) | Effect size, SMD (95% CI) | I Reference Blazer2 , % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed exercise | 7 (519) | –0.34 (–0.52 to –0.17) | 0 |

| Diagnostic criteria | 3 (195) | –0.38 (–0.67 to –0.10) | 0 |

| Symptom checklist | 4 (324) | –0.34 (–0.62 to –0.06) | 25 |

| Lowest risk of bias | 3 (404) | –0.36 (–0.61 to –0.10) | 27 |

| Active control | 4 (284) | –0.44 (–0.67 to –0.20) | 0 |

| Extended follow-up | 4 (436) | –0.32 (–0.54 to –0.10) | 19 |

SMD, standard mean difference.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The review identified nine RCTs evaluating the medium-term (3–12 months) effect of exercise on the severity of depressive symptoms in older people. Synthesised data from seven trials of mixed exercise indicated a small but statistically significant effect favouring exercise. Small, statistically significant effects favouring exercise were similarly observed in a pre-planned analysis of trials stratified by depression eligibility criteria (clinician diagnosis or symptom checklist threshold). These findings were robust in sensitivity analyses that excluded trials with higher risk of bias, non-active intervention comparison groups or in which the primary end-point was within rather than beyond the intervention period.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The study adhered to the pre-specified protocol, adopted procedures to limit the potential for bias and used appropriate methods to select, evaluate and synthesise relevant evidence. A comprehensive search for published and unpublished studies, which included multiple electronic databases and scanning of bibliographies, yielded nine trials, all of which were published studies. Absence of data from unpublished studies is a potential weakness, since effects estimated from published studies may be inflated because of bias towards the non-publication of small studies with null effects. However, null effects on the outcome of interest in five of nine included trials, and five of seven synthesised trials, mitigates concerns about publication bias, since decisions to publish appear independent of the observed effect.

There was at least a moderate risk of bias in all but three of the included trials. As study quality and effect size typically show an inverse association, the underlying risk of bias may have inflated our estimate of the treatment effect. Sensitivity analysis restricted to three trials of low risk of bias yielded a pooled estimate of a nearly identical magnitude and precision as the estimate derived from synthesis that included trials of higher risk of bias. These data are inconsistent with the suggestion that bias, due to poor methodological quality, may have inflated the observed effect of mixed exercise on symptoms of depression.

A strength of the review is that it not only provides data crucial to healthcare decision-making, such as uptake of and adherence to exercise among the target population, but that data are derived from trials conducted under conditions that most closely match the context of usual healthcare practice. Specifically, in three trials of low risk of bias, with older people who were not excluded for or prohibited from use of antidepressant medication, who were identified, approached and invited to participate in the context of routine clinical practice, 68% (417 of 616) of eligible patients agreed to participate in a trial of exercise for treatment of depression, at least three-quarters of whom achieved the minimum criteria for adherence.

Comparison with other studies

Other reviews of exercise for depression in older people Reference Sjösten and Kivelä11,Reference Blake, Mo, Malik and Thomas12 have included both randomised and non-randomised study designs, and trials in which current depression was not required for participant eligibility. Findings based on different levels of evidence in clinically heterogeneous populations are not easy to use to inform healthcare decisions. Moreover, previous reviews have used qualitative methods of synthesis and relied on quasiquantitative methods for interpretation based on a simple count of studies with/without significant results. This approach is less than ideal, not least because there is an increased potential to conclude that exercise is beneficial for depression, when the magnitude of the effect is too small to be meaningful. Our study provides the first quantitative estimate of the effect of exercise on depression severity among older people with clinically significant symptoms of depression, and pre-planned subgroup and sensitivity analyses suggest that the effect is both stable and robust.

The pooled effect of exercise on depression severity observed in this review (SMD = –0.34) is comparable with the range of effects estimated for different classes of antidepressant medication (SMD = 0.2–0.5) Reference Taylor, Meader, Bird, Pilling, Creed and Goldberg25 and psychotherapy (SMD = 0.18–0.34). Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Bohlmeijer, Hollon and Anderson26 However, although age-associated factors can complicate use of antidepressant medication and resource-related factors can impede timely access to psychotherapy, for older people with or without medical morbidity, individualised mixed exercise has very few risks, is easy to access and has the potential to improve a wide range of additional health outcomes.

Meaning and implications of the study

The clinical relevance of an SMD can more easily be considered when converted back into units of the original scale, or when represented as the overlap of distributions. At a group level, an SMD of –0.34 is equivalent to 63% of exercise participants having lower severity of depression than the average control participant or, put another way, 13% of the population of exercise participants doing better than would otherwise have been expected. For individuals at the symptom checklist threshold, an SMD of –0.34 translates into a reduction of approximately 20% in the severity of depressive symptoms. The magnitude of effect estimated in this study is clinically meaningful at the individual level, and may have substantial public health significance at the population level.

Our findings must be interpreted in relation to the quantity and quality of available evidence. For exercise interventions involving 3D training (Tai Chi and Qi Gong), two trials with a high risk of bias demonstrate clearly that evidence was insufficient in both quantity and quality. For interventions involving mixed exercise, the available evidence comprised seven trials with low to moderate risk of bias. Although the quantity and quality of evidence was less than ideal, these limitations are not sufficient to dismiss the findings of the review. Evidence is drawn from RCTs of direct relevance to the population, intervention and outcome of interest. All analyses were pre-specified, synthesised results, yielded consistent effects and there was no evidence of small study effects, including publication bias. Thus, there is a moderate-quality evidence base for the medium-term effect of mixed exercise on depression severity.

The finding that mixed exercise has a small, but clinically important effect on symptoms of depression, has general applicability to people aged over 60 years who are experiencing elevated symptoms of depression. However, as depression may reduce the appeal of exercise, participants in exercise trials may not be representative of the population of older people with depression. As none of the included trials stratified randomisation by depression severity, it is unclear whether our findings are equally applicable to patients with elevated, but subthreshold, symptoms as they are to patients with more severe symptoms, such as those that satisfy diagnostic criteria. Similarly, the findings may have limited applicability for patients who are more frequent exercisers or who have more severe comorbid physical illness, since several trials excluded patients classified as regular exercisers or as too ill to participate.

Research to reduce residual uncertainty concerning the applicability of moderate-quality evidence should be considered a public health priority. This research should be in the form of a pragmatic RCT with sufficient power to detect an effect equivalent to an SMD of at least 0.3. Such research might usefully stratify randomisation by depression severity, receipt of antidepressant medication and/or level of regular exercise. As uptake of exercise in this population will be the crucial driver for cost-effectiveness, interventions should include integrated strategies, based on behaviour change techniques, to maximise uptake of and adherence to exercise regimens.

The findings of this review are consistent with the suggestion that, for older people who present with clinically meaningful symptoms of depression, prescribing structured exercise with mixed elements of endurance and strength training tailored to individual ability, will likely reduce the severity of depression. Whereas the evidence on the effect of mixed exercise is minimally sufficient, for Tai Chi and Qi Gong the available evidence is insufficient in both quantity and quality.

Appendix Risk of bias within trials

| Risk of bias itemFootnote a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Sequence | Allocation | Masking | Follow-up | ITT | Overall riskFootnote b |

| Brenes (2007) Reference Brenes, Williamson, Messier, Rejeski, Pahor and Ip16 |

|

|

|

? | ? | Moderate |

| Chiechanowski (2004) Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner, Schmaling, Schwartz, Williams and Diehr17 |

|

|

|

|

|

Low |

| Chou (2004)? | ? | × | ? | × | High | |

| Kerse (2010) Reference Kerse, Hayman, Moyes, Peri, Robinson and Dowell22 |

|

|

|

|

|

Low |

| Mather (2002) Reference Mather, Rodriguez, Guthrie, McHarg, Reid and McMurdo20 |

|

|

|

|

|

Low |

| Sims (2006) Reference Sims, Hill, Davidson, Gunn and Huang21 |

|

|

|

× |

|

Moderate |

| Singh (2001) Reference Singh, Clements and Singh18 |

|

|

× |

|

? | Moderate |

| Tsang (2006) Reference Tsang, Fung, Chan, Lee and Chan24 | ? | ? | ? | × | × | High |

| Williams (2008) Reference Williams and Tappen19 |

|

? |

|

× |

|

Moderate |

a

![]() ,

adequate; ?, unclear; ×, inadequate.

,

adequate; ?, unclear; ×, inadequate.

b Low risk: 5 items adequate; moderate: ⩾3 items adequate and <2 items inadequate; high: ⩾2 inadequate.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.