Regulatory agencies such as the National Cancer Institute and the National Authority for Health in France recommend assessing quality of life (QoL) in daily clinical practice in patients with chronic illnesses. In particular, QoL measurements are increasingly considered to be an important way of evaluating the treatments and care provided to patients with schizophrenia.Reference Hofer, Baumgartner, Bodner, Edlinger, Hummer and Kemmler1,Reference Hofer, Baumgartner, Edlinger, Hummer, Kemmler and Rettenbacher2 Using QoL measures may provide clinicians with information regarding the general health statuses of their patients that might otherwise go unrecognised,Reference Nelson, Landgraf, Hays, Wasson and Kirk3,Reference Sprangers and Aaronson4 thereby improving patient satisfaction and health outcomes.Reference Awad and Voruganti5 Thus, clinicians should consider QoL measures in the same way as routine objective measures such as symptomatic evaluation scales, laboratory tests and radiographs to manage the care of patients.Reference Halyard, Frost, Dueck and Sloan6

Despite the acknowledged need to consider QoL issues in clinical practice, its measurement has not been routinely implemented,Reference Greenhalgh, Long and Flynn7 especially in psychiatry.Reference Awad and Voruganti5,Reference Gilbody, House and Sheldon8,Reference Boyer and Auquier9 Practical and attitudinal barriers have been described.Reference Gutteling, Busschbach, de Man and Darlington10 Obtaining QoL data in an efficient real-time manner is difficult because of feasibility issues (i.e. the lack of computer stations, hand-held devicesReference Halyard, Frost, Dueck and Sloan6). Moreover, physicians often overlook QoL assessment as a result of time pressures and clinical constraints as well as a lack of training and interest.Reference Morris, Perez and McNoe11 Therefore, more work must be undertaken to increase the use of QoL instruments in clinical practice. In particular, trials are necessary to build a satisfactory evidence base for the routine clinical use of QoL in psychiatryReference Gilbody, House and Sheldon12,Reference Luckett, Butow and King13 as has already been accomplished in oncology.Reference Takeuchi, Keding, Awad, Hofmann, Campbell and Selby14-Reference Detmar, Muller, Schornagel, Wever and Aaronson17 To our knowledge, and based on an extensive review,Reference Knaup, Koesters, Schoefer, Becker and Puschner18 only one previous randomised study in mental health has reported on the effectiveness of feedback of a standardised outcome assessment including QoL.Reference Slade, McCrone, Kuipers, Leese, Cahill and Parabiaghi19 This found no difference in the mean follow-up QoL between a treatment as usual group and a feedback group. However, the specifics of this study should be mentioned: it was performed on a heterogeneous sample with different mental health illnesses and a short follow-up time. Moreover, it lacked a third control group, including assessment without feedback, that allowed for the isolation of the effect of a single assessment. These limitations prompted us to design a prospective and randomised trial to investigate the impact of QoL assessment with feedback for clinicians regarding satisfaction and other health outcomes in patients with schizophrenia.

Method

Study site and patient eligibility

This study was conducted at the Sainte-Marguerite University Hospital, a specialised psychiatric treatment centre in Marseille, France. The sample consisted of patients who attended the day hospital over a 6-month period. All consecutive attendees who came to the day hospital were approached to participate. The inclusion criteria were: age over 18 years, diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria,20 stable disease status (no need for a hospital admission at inclusion and no major change in patient condition for 2 months prior to inclusion) and native French speaking. The exclusion criteria were: reduced capacity to consent,Reference Jeste, Palmer, Appelbaum, Golshan, Glorioso and Dunn21 an Axis I diagnosis on the DSM-IV other than schizophrenia, acute decompensation of organic disease or mental retardation. The patients were provided with both oral and written information regarding the study prior to obtaining their informed consent. The local ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Méditerranée V, France, trial number 07 067) and the French drug and device regulation agency (Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé, France, trial number A01033-50) approved this study.

Design

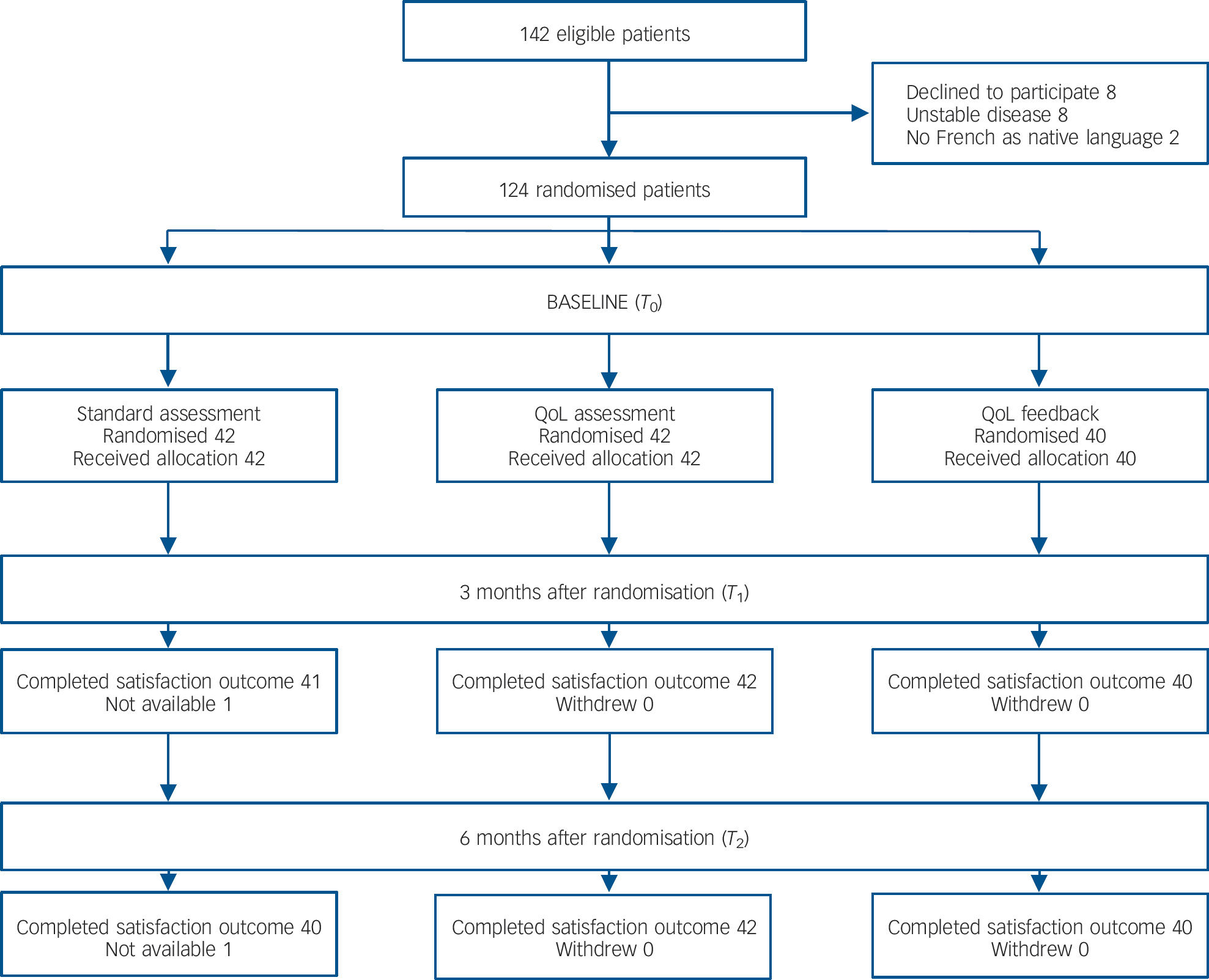

The present study was a 6-month, prospective, randomised, controlled, open-label and single-centre study. Figure 1 displays a flow chart of the study. A computer-generated, randomised list was created using a permuted block design. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the three groups (random assignment 1:1:1). These were (a) a standard psychiatric assessment group: patients completed the standard psychiatric assessment; (b) a QoL assessment group: patients completed a QoL questionnaire in addition to the standard psychiatric assessment; and (c) a QoL feedback group: feedback regarding the QoL scores was presented to clinicians in addition to the standard psychiatric assessment. The purpose of the QoL assessment group was to isolate the effect of a single assessment (i.e. without feedback) in the clinical use of QoL. Evaluations were performed at three different time points: (a) at randomisation (baseline; T 0) as well as 3 months (T 1) and 6 months (T 2) after randomisation.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of participant progress through the phases of the study.

Groups

Standard psychiatric assessment group

In this group each patient received a standard psychiatric assessment performed by a multidisciplinary team that included a psychiatrist, a clinical psychologist, a nurse and a social worker when appropriate. The standard psychiatric assessment was based on a face-to-face interview, clinical examination and standardised tools (i.e. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),Reference Kay, Opler and Fiszbein22,Reference Lancon, Reine, Llorca and Auquier23 Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS),Reference Addington, Addington and Maticka-Tyndale24,Reference Lancon, Auquier, Reine, Toumi and Addington25 Extrapyramidal Symptoms Rating Scale (ESRS)Reference Chouinard and Margolese26 and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)Reference Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss and Cohen27). Special attention was given to psychotic and depressive symptoms, drug-induced movement disorders and global functioning. This assessment may therefore play a role in the: (a) assessment of the clinical stability of the patient (for example symptomatic and functional remission); (b) detection and prevention of comorbid somatic and psychiatric disorders; (c) initiation or adaptation of specific pharmacological treatments; (d) evaluation of drug-induced disorders; (e) initiation of psychosocial therapy such as cognitive remediation and psychosocial rehabilitation; and (f) addressing of the administrative and financial issues (e.g. health insurance, free state aid).

QoL assessment group

In this group patients received a self-administered QoL questionnaire at each evaluation. Patients completed and returned the questionnaire to a research assistant before the standard psychiatric assessment. The research assistant was independent of the care team, and the QoL scores were not returned to the clinicians. Quality of life was assessed using the S-QoL questionnaire, which is a self-administered questionnaire designed for people with schizophrenia.Reference Auquier, Simeoni, Sapin, Reine, Aghababian and Cramer28 The S-QoL is a multidimensional, 41-item instrument that was developed based on patient views, and assesses eight dimensions: psychological well-being, self-esteem, family relationships, relationships with friends, resilience, physical well-being, autonomy, and sentimental life; and a total score. Dimension and index scores range from 0 (low QoL) to 100 (high QoL).

QoL feedback group

In this group the patient completed and returned the S-QoL questionnaire to the research assistant at each evaluation. The assistant entered the item scores on a computer. A specific algorithm program calculated QoL scores. These scores and the scores of previous evaluations were provided to the care team before the standard psychiatric assessment. In addition, population normsReference Auquier, Simeoni, Sapin, Reine, Aghababian and Cramer28,Reference Boyer, Simeoni, Loundou, D'Amato, Reine and Lancon29 were provided to help clinicians interpret QoL scores. No other advice or guidelines regarding data interpretation and use were provided to clinicians. Patient management was entirely at the discretion of the treating physician.

Evaluation criteria

Primary criterion

The primary evaluation criterion was patient satisfaction, which was assessed using three items relating to different satisfaction domains including: global satisfaction; satisfaction/trust with the staff/care; and satisfaction/trust with the care structure. Because no valid French satisfaction questionnaire for out-patients with schizophrenia is available, ‘ad hoc’ questions were elaborated/created according to the items of the QSH-45, which is a well-validated French in-patient satisfaction questionnaire,Reference Antoniotti, Baumstarck-Barrau, Simeoni, Sapin, Labarere and Gerbaud30 and from our own experience.Reference Boyer, Baumstarck-Barrau, Cano, Zendjidjian, Belzeaux and Limousin31 Three questions were developed by the steering committee project: (a) What is your degree of satisfaction regarding your global care management?; (b) What is your degree of satisfaction regarding the care structure?; and (c) What is your degree of satisfaction regarding the care staff? The primary criterion was global satisfaction at T 2, and the other items were considered as secondary criteria. All items were worded positively and assessed using a four-point Likert scale from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 4 (very satisfied). Satisfaction was assessed at T 1 and T 2.

Secondary criteria

We used PANSS to assess psychotic symptomatology. This scale is composed of three subscales: positive, negative and general psychopathology.Reference Kay, Opler and Fiszbein22,Reference Lancon, Reine, Llorca and Auquier23 Higher scores indicate more severe symptomatologies. We used the CDSS to examine depressive symptomatology; it uses a nine-item scale that evaluates depression independent of extrapyramidal and negative symptoms.Reference Addington, Addington and Maticka-Tyndale24,Reference Lancon, Auquier, Reine, Toumi and Addington25 The CDSS is specifically designed for patients with schizophrenia. Higher scores indicate greater levels of depression. Drug-induced movement disorders (such as Parkinsonism, akathisia, dystonia and dyskinesia) were evaluated using the ESRS.Reference Chouinard and Margolese26 Higher scores indicate more severe disorders. Global functioning was assessed using GAF. The GAF considers psychological, social and occupational functioning, and scores range from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate higher levels of functioning.Reference Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss and Cohen27 Disease severity was assessed using the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity scale. The CGI classifies disease severity as mild, moderate or severe.Reference Guy32 Psychotic symptomatology, depression, drug-induced movement disorders, global functioning and severity of disease were assessed at T 0, T 1 and T 2. The psychiatrist indicated any medication changes between T 0 and T 1 as well as between T 1 and T 2.

Additional data

The following parameters were recorded for each participant: gender, age, education level (<12 years/⩾12 years), living arrangement (partner or parents/alone) and employment status (no/yes).

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were compared across the three groups. Frequencies were compared using chi-squared tests, and quantitative variables were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks with a post hoc Dunnett's test. The proportions of patient global satisfaction at T 2 (primary criterion) were compared across the three groups. Group comparisons with regard to the other scores (i.e. the PANSS positive, negative and general psychopathologies as well as CDSS, ESRS and GAF scores) were performed using analysis of variance. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0.

Results

Participants

Of the 142 patients who were eligible, 124 participants were enrolled: 42 were enrolled in the standard psychiatric assessment group, 42 in the QoL assessment group and 40 in the QoL feedback group. All but two patients in the standard psychiatric assessment group completed the 3- and 6-month assessments (Fig. 1). The mean age of participants was 41.1 years (s.d. = 11.8); 67.7% were male, and 21.8% had at least 12 years of education. These patients were mildly ill, with a mean total PANSS score of 63.0 (s.d. = 21.6) and positive, negative and general psychopathology subscale scores of 12.9 (s.d. = 5.9), 15.6 (s.d. = 6.3) and 34.6 (s.d. = 11.5) respectively. Patient characteristics did not differ across the three groups at baseline (Table 1). The proportion of highly satisfied patients in the entire sample ranged from 64.2 to 68.3% at 3 months and from 61.5 to 65.6% at 6 months (Table 2).

The effects of QoL assessment and feedback on patient satisfaction

Global satisfaction and satisfaction/trust with the care structure significantly differed across the three groups at the 6-month follow-up (Table 2): a significantly larger percentage of patients reported high levels of satisfaction in the QoL feedback group compared with the standard psychiatric assessment and QoL assessment groups with regard to these domains. In particular, global satisfaction was significantly higher in the QoL feedback group (72.5% patients had high levels of satisfaction) compared with the standard psychiatric assessment (67.5%) and QoL assessment groups (45.2%; P = 0.025). This trend towards higher satisfaction in the QoL feedback group was also found at the 3-month follow-up visit with regard to global satisfaction and satisfaction/trust with the staff/care. A total of 75%, 68.3% and 50.0% of patients in the QoL feedback, standard psychiatric assessment and QoL assessment groups, respectively, reported high levels of global satisfaction (P = 0.049).

Table 1 Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between the three groups at baseline (T0)

| Total (n = 124) | Standard assessment group (n = 42) | QoL assessment group (n = 42) | QoL feedback group (n = 40) | P Footnote a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 41.08 (11.77) | 41.95 (12.05) | 41.76 (13.14) | 39.45 (9.92) | 0.582 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Men | 84 (67.7) | 32 (76.2) | 27 (64.3) | 25 (62.5) | 0.349 |

| Women | 40 (32.3) | 10 (23.8) | 15 (35.7) | 15 (37.5) | |

| Educational level, n (%) | |||||

| <12 years | 97 (78.2) | 37 (88.1) | 29 (69.0) | 31 (77.5) | 0.106 |

| ⩾12 years | 27 (21.8) | 5 (11.9) | 13 (31.0) | 9 (22.5) | |

| Partnership status, n (%) | |||||

| Not single | 69 (55.6) | 25 (59.5) | 22 (52.4) | 22 (55) | 0.801 |

| Single | 55 (44.4) | 17 (40.5) | 20 (47.6) | 18 (45.0) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||||

| No | 107 (86.3) | 37 (88.1) | 35 (83.3) | 35 (87.5) | 0.788 |

| Yes | 17 (13.7) | 5 (11.9) | 7 (16.7) | 5 (12.5) | |

| Clinical | |||||

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Total | 63.01 (21.59) | 64.74 (19.24) | 64.19 (23.58) | 59.87 (21.96) | 0.445 |

| Positive | 12.90 (5.92) | 13.33 (5.72) | 13.36 (6.81) | 11.95 (5.09) | 0.530 |

| Negative | 15.56 (6.27) | 16.33 (6.22) | 15.50 (6.67) | 14.79 (5.92) | 0.395 |

| General psychopathology | 34.55 (11.48) | 35.07 (9.87) | 35.33 (12.20) | 33.13 (12.44) | 0.445 |

| Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia, mean (s.d.) | 4.47 (3.57) | 4.90 (3.84) | 4.4 (3.231) | 4.05 (3.65) | 0.604 |

| Extrapyramidal Symptoms Rating Scale, mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Dyskinesia | 0.09 (0.38) | 0.19 (0.59) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.183 |

| Parkinsonism | 0.12 (0.54) | 0.21 (0.81) | 0.10 (0.37) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.495 |

| Dystonia | 0.06 (0.23) | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.580 |

| Akathisia | 0.07 (0.34) | 0.14 (0.47) | 0.07 (0.34) | 0 (0) | 0.135 |

| Global Assessment of Functioning, mean (s.d.) | 61.94 (13.18) | 60.9 (13.67) | 61.57 (12.36) | 63.43 (13.66) | 0.604 |

| Clinical Global Impression of Severity, n (%) | 0.678 | ||||

| Mild | 39 (31.5) | 12 (28.6) | 12 (28.6) | 15 (37.5) | |

| Moderate | 68 (54.8) | 23 (54.8) | 26 (61.9) | 19 (47.5) | |

| Severe | 17 (13.7) | 7 (16.7) | 4 (9.5) | 6 (15.0) |

QoL, quality of life.

a. P-value Kruskall-Wallis test or χ2 test.

Table 2 Comparison of patients' satisfaction between the three groups at 3 and 6 months

| n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 124) | Standard assessment group | QoL assessment group (n = 42) | QoL feedback group (n = 40) | P Footnote a | |

| T 1 (3 months) | |||||

| n | 123 | 41 | 42 | 40 | |

| Global satisfaction | 0.049 | ||||

| From unsatisfied to mild satisfied | 44 (35.8) | 13 (31.7) | 21 (50.0) | 10 (25.0) | |

| Very satisfied | 79 (64.2) | 28 (68.3) | 21 (50.0) | 30 (75.0) | |

| Satisfaction with staff/care | 0.029 | ||||

| From unsatisfied to mild satisfied | 41 (33.3) | 13 (31.7) | 20 (47.6) | 8 (20.0) | |

| Very satisfied | 82 (66.7) | 28 (68.3) | 22 (52.4) | 32 (80.0) | |

| Satisfaction with the care structure | 0.153 | ||||

| From unsatisfied to mild satisfied | 39 (31.7) | 10 (24.4) | 18 (42.9) | 11 (27.5) | |

| Very satisfied | 84 (68.3) | 31 (75.6) | 24 (57.1) | 29 (72.5) | |

| T 2 (6 months) | |||||

| n | 122 | 40 | 42 | 40 | |

| Global satisfaction | 0.025 | ||||

| From unsatisfied to mild satisfied | 47 (38.5) | 13 (32.5) | 23 (54.8) | 11 (27.5) | |

| Very satisfied | 75 (61.5) | 27 (67.5) | 19 (45.2) | 29 (72.5) | |

| Satisfaction with staff/care | 0.095 | ||||

| From unsatisfied to mild satisfied | 42 (34.4) | 14 (35.0) | 19 (45.2) | 9 (22.5) | |

| Very satisfied | 80 (65.6) | 26 (65.0) | 23 (54.8) | 31 (77.5) | |

| Satisfaction with the care structure | 0.025 | ||||

| From unsatisfied to mild satisfied | 42 (34.4) | 12 (30.0) | 21 (50.0) | 9 (22.5) | |

| Very satisfied | 80 (65.6) | 28 (70.0) | 21 (50.0) | 31 (77.5) | |

QoL, quality of life.

a. Bold values: P<0.05.

Table 3 Comparison of secondary criteria between the three groups at 6 months

| Total (n = 124) | Standard assessment group (n = 42) | QoL assessment group (n = 42) | QoL feedback group (n = 40) | P Footnote a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Total | 61.20 (20.53) | 64.64 (20.20) | 60.55 (20.58) | 58.28 (20.81) | 0.227 |

| Positive | 12.48 (5.48) | 13.47 (5.79) | 12.36 (5.64) | 11.58 (4.91) | 0.223 |

| Negative | 15.21 (5.94) | 16.07 (5.94) | 15.07 (5.88) | 14.45 (6.03) | 0.358 |

| General psychopathology | 33.51 (10.65) | 35.10 (10.30) | 33.12 (10.67) | 32.25 (11.05) | 0.312 |

| Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia, mean (s.d.) | 3.63 (2.90) | 4.19 (3.00) | 3.5 (2.73) | 3.18 (2.97) | 0.229 |

| Extrapyramidal Symptoms Rating Scale, mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Dyskinesia | 0.07 (0.34) | 0.14 (0.52) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.364 |

| Parkinsonism | 0.13 (0.54) | 0.24 (0.82) | 0.1 (0.37) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.299 |

| Dystonia | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.621 |

| Akathisia | 0.08 (0.35) | 0.14 (0.47) | 0.07 (0.34) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.364 |

| Global Assessment of Functioning, mean (s.d.) | 64.57 (12.97) | 62.36 (13.33) | 65.12 (12.12) | 66.33 (13.43) | 0.273 |

| Clinical Global Impression of Severity, n (%) | 0.938 | ||||

| Mild | 36 (29.0) | 11 (26.2) | 12 (28.6) | 13 (32.5) | |

| Moderate | 74 (59.7) | 25 (59.5) | 26 (61.9) | 23 (57.5) | |

| Severe | 14 (11.3) | 6 (14.3) | 4 (9.5) | 4 (10.0) | |

| Medication change, n (%)Footnote b | 0.374 | ||||

| Yes | 15 (12.4) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (7.5) | 7 (17.9) | |

| No | 106 (87.6) | 37 (88.1) | 37 (92.5) | 32 (82.1) |

a. P-value Kruskall-Wallis test or χ2 test.

b. The data for medication changes are based on: total n = 121, Standard assessment group n = 42, QoL assessment group n = 40, QoL feedback group n = 39.

No significant group effect was observed with regard to the different clinical outcomes and changes in medication at the 3-month (data not shown) and 6-month follow-up visits (Table 3). Importantly, there was a trend towards better clinical outcomes (PANSS, CDSS, ESRS, GAF and CGI scores) in the QoL feedback group that was present at 3 months and continued at 6 months. Although not significant, there were more changes made to medication in the QoL feedback group.

Discussion

This randomised study is the first to provide an evidence base for the routine clinical use of QoL assessment and feedback in the management of patients with schizophrenia. Of particular interest is the finding that patient satisfaction levels were higher when clinicians were provided with QoL assessments compared with that of patients whose clinicians did not have this information. This finding is consistent with previous oncology studies reporting that feedback of QoL scores to clinicians improves patient-physician communication.Reference Takeuchi, Keding, Awad, Hofmann, Campbell and Selby14-Reference Detmar, Muller, Schornagel, Wever and Aaronson17 Quality of life measures may help to understand the subjective experiences that are key in treating people with mental disordersReference Yang, Mulvey and Falissard33 and improve patient-clinician communication. Moreover, better communication is related to decreases in the paternalistic view of care as well as increases in interactive approaches with patients and patient decision-making, all of which lead to increased patient satisfaction.Reference Thind and Maly34,Reference Nordon, Rouillon, Barry, Gasquet and Falissard35 We thus hypothesise that QoL assessment with feedback may provide useful information to psychiatrists, which leads to better clinician-patient communicationReference Detmar, Muller, Schornagel, Wever and Aaronson17 and clinician awareness/detection of patients' social and psychological problems,Reference Sprangers and Aaronson4 and that this plays a part in enhancing satisfaction. In addition, our findings provide strong support for integrating QoL assessment and feedback with standard psychiatric assessments. In fact, patient satisfaction predicts future behaviours including adherence with treatment, intent to return for careReference Cleary and McNeil36-Reference Ware and Davies38 and final health outcomes.Reference Chue39 Thus far, obtaining QoL data in an efficient, real-time manner was difficult and rare in clinical practice.Reference Halyard, Frost, Dueck and Sloan6,Reference Gutteling, Busschbach, de Man and Darlington10 Priority should be given to strategies to implement QoL measurements in routine practice, including providing systematic feedback for clinicians. The logistics of obtaining patient QoL data should be the same as those for other clinical indicators.Reference Halyard, Frost, Dueck and Sloan6,Reference Halyard, Frost and Dueck40 Interestingly, recent technologies such as electronic medical records are being implemented in psychiatric settings;Reference Boyer, Baumstarck-Barrau, Belzeaux, Azorin, Chabannes and Dassa41-Reference Boyer, Renaud, Limousin, Henry, Caietta and Fieschi43 these methods may efficiently and automatically collect QoL data.Reference Gutteling, Busschbach, de Man and Darlington10,Reference Wright, Selby, Crawford, Gillibrand, Johnston and Perren44,Reference Velikova, Wright, Smith, Cull, Gould and Forman45

Despite the positive effect that QoL assessment with feedback had on patient satisfaction (i.e. there was a trend towards improved clinical outcomes in the QoL feedback group), there was no significant effect on other health outcomes (PANSS, CDSS, ESRS, GAF and CGI scores) or patient management (changes in medication). The failure to detect significant between-group differences may be because of the small sample size of each group. Alternatively, this failure might be because the disease severity of our sample tended to be mild, which left little room for health status improvements, especially given the relatively short 6-month follow-up period of our study.Reference Hodgson, Bushe and Hunter46 However, these findings are consistent with previous studies that have failed to report any changes in clinical management or health outcomes.Reference Luckett, Butow and King13,Reference Rosenbloom, Victorson, Hahn, Peterman and Cella47 Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that clinicians did not optimally use the QoL feedback. In particular, studies have suggested that clinicians did not feel comfortable interpreting QoL data to improve QoL of patients.Reference Halyard, Frost, Dueck and Sloan6,Reference Halyard, Frost and Dueck40 Strategies for the implementation of QoL measurements should include training sessions aimed at motivating professionals to use QoL data and provide norms, advice and guidelines regarding data interpretation and patient management.Reference Luckett, Butow and King13

One last finding was particularly important in our study. Quality of life assessments without feedback for clinicians was associated with lower patient satisfaction levels compared with patients whose clinicians were provided with QoL feedback and those whose QoL was not assessed. This finding suggests a QoL-assessment nocebo effect (i.e. negative expectations that derived from the clinical encounter and led to poor therapy adherence and health outcomesReference Colloca and Finniss48). Measuring QoL may cause ‘side-effects’ through the exploration of sensitive subjects, thereby generating new expectations from clinicians on the part of the patients.Reference Higginson and Carr49 The absence of the appropriate clinical use of these QoL data (i.e. examine, interpret and act) might negatively affect patient satisfaction (i.e. create a match or mismatch between patient expectations and perceptionsReference Addington, Addington and Maticka-Tyndale24). Thus, this finding has direct implications for both research and clinical practice. Clinicians should consider possible nocebo effects.

Limitations and perspectives

Certain limitations of this study must be considered carefully. First, the sample might not be representative of the entire population of patients with schizophrenia. The participants had paranoid schizophrenia, and were mostly male, middle aged, with mild disease severity and more than 5 years of illness duration. Likewise, the clinicians might not be representative of all of their colleagues in the mental healthcare system because the study was conducted at one university hospital. Therefore, replication is needed in other settings using more diverse and larger groups of patients and clinicians.

Second, clinicians treated patients from all three study groups; this design may have contaminated the results. Therefore, the differences between each group may be underestimated. Future studies should better control for contamination effects, especially by using a randomised cluster design.Reference Luckett, Butow and King13

Third, a longer follow-up period is necessary to better explore the impact of QoL assessment and feedback on clinical outcomes and changes in patient managementReference Luckett, Butow and King13 as well as to confirm the trend towards improved clinical outcomes in the QoL feedback group. Studying the effect of measuring QoL on other relevant outcomes such as social variables (i.e. how patients live, function in society and perform various roles)Reference Priebe50 or recovery (i.e. subjective changes in how people appraise their lives and the extent to which they view themselves as meaningful agents in the world) would be necessary to evaluate long-term outcomes.Reference Lysaker, Glynn, Wilkniss and Silverstein51,Reference Roe, Mashiach-Eizenberg and Lysaker52

Fourth, our approach for measuring satisfaction, which was not based on a validated questionnaire but rather on three ad hoc questions, is debatable. At the beginning of the project, no validated questionnaire assessing patient satisfaction in psychiatry was available in French. However, it can be assumed that the choice of the three questions was both reasonable and pragmatic. The three items were: (a) developed from a standardised and well-validated questionnaire of patients' satisfaction with care;Reference Addington, Addington and Maticka-Tyndale24,Reference Barlesi, Barrau, Loundou, Doddoli, Simeoni and Auquier53,Reference Barlesi, Boyer, Doddoli, Antoniotti, Thomas and Auquier54 (b) identified as relevant both from an extensive review of the literature on this topicReference Lancon, Auquier, Reine, Toumi and Addington25 and by the steering committee of this project; and (c) in accordance with current standards in terms of content and response modalities.Reference Boyer, Baumstarck-Barrau, Belzeaux, Azorin, Chabannes and Dassa41,Reference Crocker and Algina55 The measurement bias can be considered to be minimal.

Finally, our findings concern only patients with schizophrenia and might not be generalisable to all mental disorders and chronic diseases. The current findings need to be replicated in future studies that include other chronic diseases.

Implications

Our study indicates that QoL assessment with feedback for clinicians has a positive impact on patient's satisfaction. This finding confirms the relevance of including QoL in clinical practice. However, the absence of a significant effect of QoL assessment with feedback on clinical outcomes suggests that clinicians did not optimally use these data. In addition to feedback, providing advice and guidelines regarding data interpretation and use is necessary to ensure that QoL data have direct implications for clinical practice. Finally, our findings suggest a nocebo effect of QoL assessment without feedback that clinicians should consider.

Funding

This work was supported by institutional grants from the 2005 Programme Hospitalier Recherche Clinique National. The sponsor was the Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Marseille, France; and its role was to control the appropriateness of ethical and legal considerations.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the patients for their participation in the study. The authors thank the clinicians who identified potential participants for the trial, Dr Marie-Claude Simeoni for her technical assistance, Elodie Guilhot for her contribution for the statistical analyses, Therese Vigne for the data entry.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.