Schipkowensky, Reference Schipkowensky and Arieta1 Gudjonsson & Petursson, Reference Gudjonsson and Petursson2 and Coid Reference Coid3 suggested that the rate of homicide by the mentally ill is associated with the prevalence of mental illness and is thus unrelated to the rate of other homicides. Coid went so far as to propose two ‘epidemiological laws’ regarding the incidence of homicide due to mental disorder and suggested that there is a fixed rate of about 0.13 per 100 000 population per year in all countries, regardless of the overall rate of homicide. Reference Coid3 Coid's epidemiological laws are still cited Reference Taylor and Gunn4–Reference Coid, Yang, Roberts, Ullrich, Moran, Bebbington, Brugha, Jenkins, Farrell, Lewis and Singleton6 despite studies from Sweden, Reference Fazel and Grann7,Reference Lindqvist8 the USA, Reference Boudouris9,Reference Wilcox10 Barbados Reference Evans and Malesu11 and some Japanese prefectures Reference Hata, Kominato, Shimada, Takizawa, Fujikura, Morita, Funayama, Yoshioka, Touda, Gonmori, Misawa, Sakairi, Sakamoto, Tanno, Thaik-Oo, Kiuchi, Fukumoto and Sato12 that have shown annual rates between two to four times higher than 0.13 per 100 000. Furthermore, most studies that report a high rate of homicide due to mental disorder were conducted in countries with a high total homicide rate Reference Boudouris9–Reference Hata, Kominato, Shimada, Takizawa, Fujikura, Morita, Funayama, Yoshioka, Touda, Gonmori, Misawa, Sakairi, Sakamoto, Tanno, Thaik-Oo, Kiuchi, Fukumoto and Sato12 and in the USA, with the highest rate of homicide among higher-income countries, a large proportion of incarcerated homicide offenders are thought to be mentally ill. Reference James and Glaze13 The findings of these further studies suggest that sociological and legal factors affect both the total rate of homicides and the rate of homicides due to mental disorder.

The first of Coid's epidemiological laws holds that the higher the rate of homicide in a population, the lower the proportion of homicide offenders that are mentally disordered. Reference Coid3 The existence of this law was supported by an interpretation of Home Office statistics from England and Wales that showed a decline in the proportion of homicides due to mental disorder, and a rise in the total number of homicides in England and Wales between 1957 and 1995. Reference Taylor and Gunn4 However, if homicide due to mental disorder had been constant, the decline in the proportion of such homicides from 50% to 10% of all homicides could only have been explained by a 10-fold increase in total homicides. In fact, much of the decline in the proportion of homicides due to mental disorder appears to be due to a fall in the rate of such homicides since the 1970s.

In this paper, we re-examine the official homicide statistics from England and Wales and the proposition that statistics for homicide due to mental disorder have been stable over time.

Method

We located four sets of homicide statistics for England and Wales; Taylor & Gunn, Reference Taylor and Gunn4 Gibson & Klein, Reference Gibson and Klein14,Reference Gibson and Klein15 Richards Reference Richards16 and Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Hird and Povey17

Statistics for homicides due to mental disorder are more complete after 1957, when the defence of diminished responsibility was introduced and the mandatory death penalty was abolished.

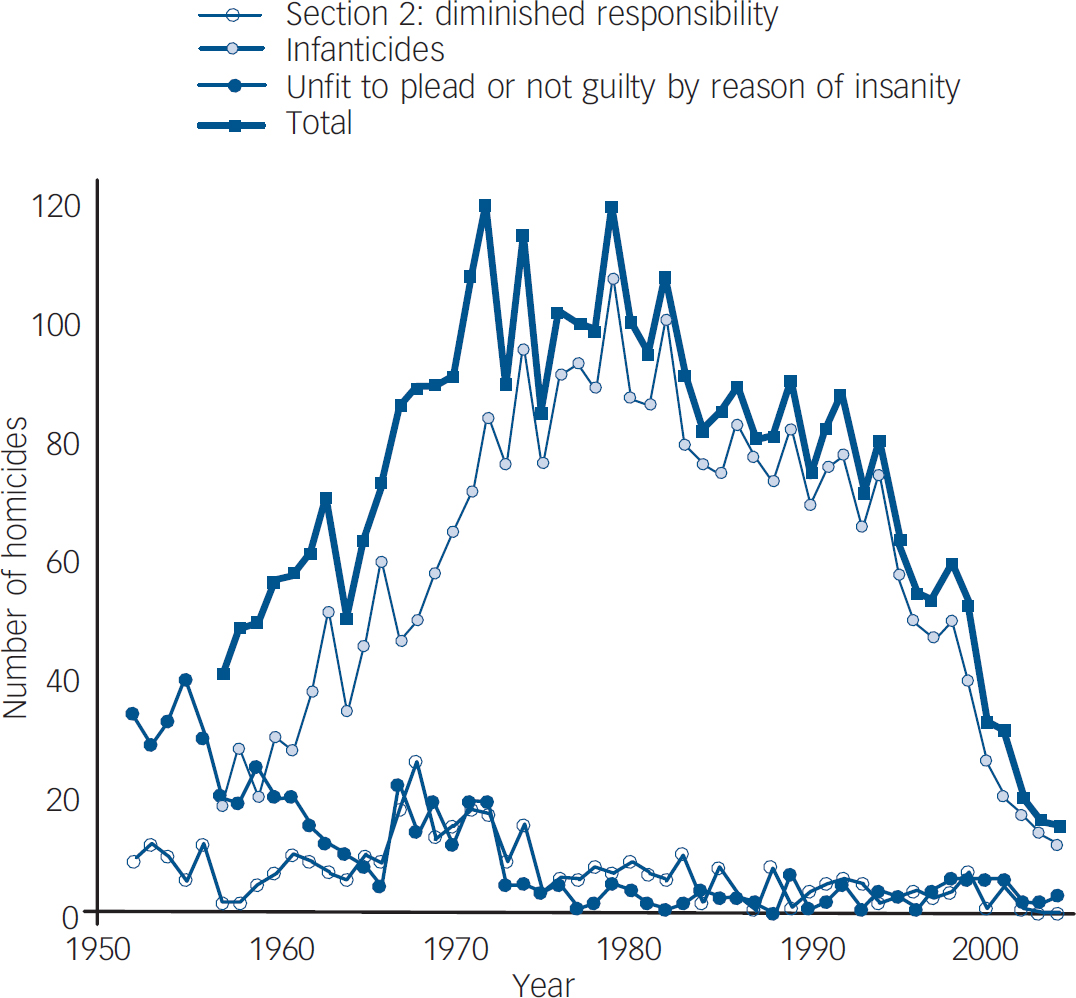

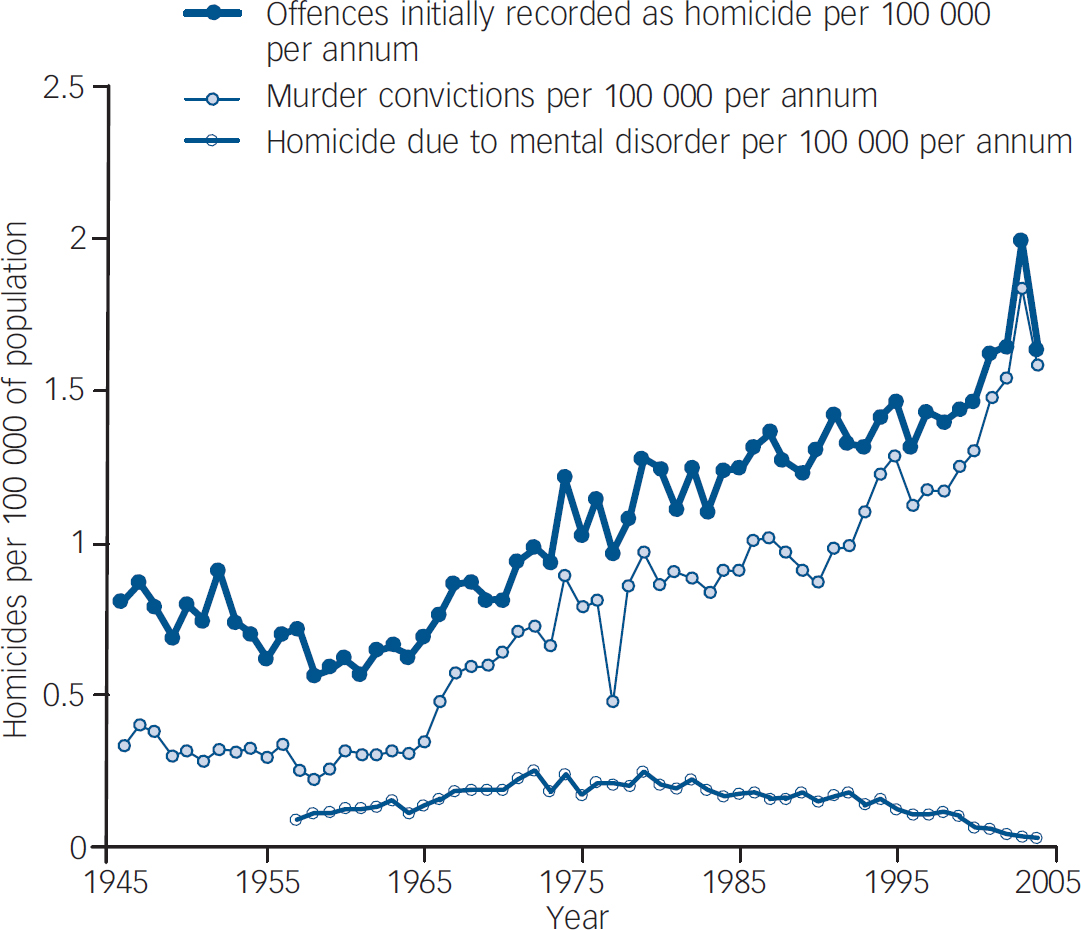

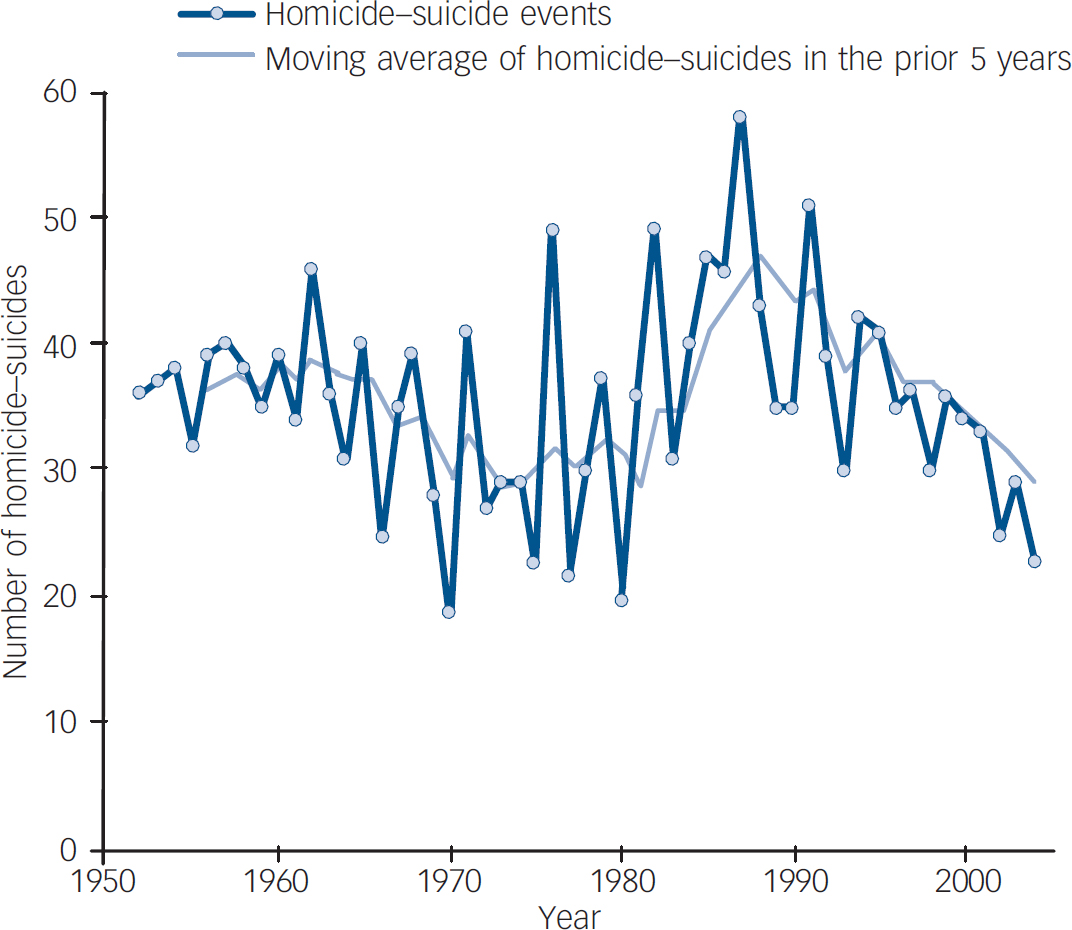

For the purpose of consistency we used the same definition of mental disorder as Taylor & Gunn, Reference Taylor and Gunn4 which is the total of the findings of Section 2 under the Homicide Act 1957 (diminished responsibility), infanticide, not guilty by reason of insanity and permanent unfitness to stand trial (see Appendix). We also chart the trends in the components of homicide due to mental disorder (Figs. 1 and 2) and homicide–suicides (Fig. 3). Taylor & Gunn did not include homicide–suicides in the mental disorder group, as it is not known what proportion of homicide–suicide offenders are also ‘mentally abnormal’ (e.g. those unfit to stand trial, not guilty by reason of insanity, with diminished responsibility or infanticide). Reference Taylor and Gunn4 Homicide–suicide statistics are examined separately in this paper. Non-age-adjusted homicide rates per 100 000 were calculated using population figures from census data, Reference Hicks and Allen18 using an assumption of linear population growth between each census.

Independent data extraction by M.L. and G.S. did not result in any discrepancies. The annual number of homicides attributed to mental disorder was taken from Taylor & Gunn (1957–1992) Reference Taylor and Gunn4 and Coleman et al (1993–2004). Reference Coleman, Hird and Povey17 The annual numbers of offences initially recorded as homicide were taken from Richards Reference Richards16 (1946–1992) and Coleman et al Reference Coleman, Hird and Povey17 (1992–2004), and total murder convictions were taken from Gibson & Klein Reference Gibson and Klein14,Reference Gibson and Klein15 (1946–1956), Taylor & Gunn Reference Taylor and Gunn4 (1957–1992) and Coleman et al Reference Coleman, Hird and Povey17 (1993–2004). Figures for the finding of not guilty by reason of insanity, unfit to stand trial, infanticide and homicide–suicide were taken from Gibson & Klein Reference Gibson and Klein14,Reference Gibson and Klein15 (1952–1956), Taylor & Gunn Reference Taylor and Gunn4 (1957–1992) and Coleman et al Reference Coleman, Hird and Povey17 (1993–2004). The 172 victims of Dr Harold Shipman, most of whom died in preceding years, were included in official statistics in 2003. Reference Coleman, Hird and Povey17

Later legal redetermination of cases may have caused some discrepancies in homicide numbers between the four sets of homicide statistics. The total number of annual homicides after 1967 taken from statistics held by the House of Commons library and reported by Richards Reference Richards16 were 17% (s.d.=14) greater than the Home Office statistics reported in Taylor & Gunn. Reference Taylor and Gunn4 However, an analysis of the trends and associations using total homicide figures from Richards Reference Richards16 was very similar to that of Taylor & Gunn Reference Taylor and Gunn4 and was hence not reported. There were only minor differences between the figures reported by Gibson & Klein, Reference Gibson and Klein14,Reference Gibson and Klein15 Coleman et al Reference Coleman, Hird and Povey17 and Taylor & Gunn Reference Taylor and Gunn4 for the periods in which the statistics overlapped. Where there was a discrepancy, the most recent statistics were used.

We examined changes in mentally disordered homicide over time using Kendall's tau, and in relation to total homicide using linear regression. Statistics were performed using SPSS version 15.0 for Windows.

Results

Changes in homicide due to mental disorder over time

The annual number of homicides due to mental disorder rose from under 50 in 1957 to well above 100 by the 1970s. The highest annual rate of 0.245 per 100 000 population was in 1973 and the absolute number peaked in 1979. During this period (1957–1980), homicides due to mental disorder and total homicides were strongly correlated (Kendall's tau=0.747, two-tailed significance P<0.0001).

In the subsequent 24 years (1981–2004) homicides due to mental disorder declined and were negatively correlated with the rate of homicide by people without mental disorder (Kendall's tau=–0.829, two-tailed significance P<0.0001). The absolute number of homicides due to mental disorder fell to levels not seen since the early 1950s and the rate has been at historic lows of 0.07 per 100 000 or lower since 2000 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Homicides due to mental disorder in England and Wales, 1952–2004.

The true figures from 2000 onwards may eventually be higher as about 10% of legal proceedings from 2000 and 20% from 2003 were not concluded. Reference Coleman, Hird and Povey17

Most of the increase in homicides that were recorded as being due to mental disorder was a result of an increase in verdicts of diminished responsibility. However, there were also peaks in infanticide, homicide offenders who were found not guilty by reason of insanity and among those found unfit for trial in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Fig. 1).

Relationship between rates and proportions of homicide due to mental disorder and other homicides

The proportion of homicides due to mental disorder fell over the period 1957–2004 as a result of two separate trends (Fig. 2). In the first 24 years (1957–1980) there was a very strong relationship between the rates of homicide due to mental disorder and other homicides (r=0.898, r 2=0.806, t=6.877, P<0.0001). In this period the proportion of homicide offenders who were mentally ill fell, despite the rise in homicides due to mental disorder, as the total homicide rates also increased. In the second period (1981–2004), the rates of homicide due to mental disorder and other homicides were negatively correlated (r=–0.920, r 2=0.846, t=–11.00, P<0.0001) and the proportion of homicides due to mental disorder also fell because the annual number declined significantly, whereas the rate of other homicides continued to rise.

Homicide followed by suicide

Homicide followed by suicide was considered separately and did not follow the pattern of homicide due to mental disorder. There was a small but significant fall in murder–suicides in the period after the abolition of the death penalty in November 1965. Between 1952 and 1965 there were 1928 homicides of which 521 (27%) were homicide–suicides, whereas between 1966 and 2004 there were 19 236 homicides of which 1357 were homicide–suicides (7.1%) (χ2=865, d.f.=1, P<0.001). The fall in the proportion of homicide–suicides is mainly explained by the rise in total homicides, but the total number of homicide–suicides also fell from 37.2 per year (s.d.=3.76) in the 14 years before the abolition of the death penalty to 30.9 per year (s.d.=8.32) during the following 14 years (unpaired two-tailed t-test, t=2.57, d.f.=26, P=0.016) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 Homicide rates in England and Wales, 1946–2004.

Fig. 3 Homicide–suicides in England and Wales, 1952–2004.

Discussion

Gibson & Klein Reference Gibson and Klein14 and Morris & Blom-Cooper Reference Morris, Blom-Cooper and Wolfgang19 reported that the homicide rate was fairly stable between 1900 and 1959 at about 0.3 per 100 000 per annum. Total homicides rose steadily in the next 45 years and by the year 2000 there were more than 1.5 homicide convictions per 100 000 population in England and Wales. Our analysis of official figures shows that the rate of homicide due to mental disorder also rose from the mid-1950s, but reached a peak in 1973 and then steadily declined to reach historically low levels. However, the reasons for the rise and fall in the rate of homicide by people who were legally classified as being mentally disordered after committing a homicide cannot be determined from these data.

Explanations for changes in homicide rates

One possible explanation for both the rise and fall in homicides due to mental disorder may have been changes in the threshold for the finding of a verdict of diminished responsibility, the largest group of such homicides. However, there have been no changes to the official definitions of the defences to murder since the reforms of the mid-1950s, 20 and change in the threshold for diminished responsibility is unlikely to have had an influence on findings of infanticide, not guilty by reason of insanity or unfit to stand trial, which also peaked between 1965 and 1975 and then fell.

Another possibility is that methods of detecting mental disorder before trial have changed over the past 50 years. Fazel & Grann Reference Coid, Yang, Roberts, Ullrich, Moran, Bebbington, Brugha, Jenkins, Farrell, Lewis and Singleton6 concluded that the high rate of mental disorder among homicide offenders in Sweden was a result of closer psychiatric scrutiny of Swedish offenders. If anything, the detection of mental illness among prisoners is more likely to have improved over the past 50 years and it seems unlikely that there has been a decline in the ability of courts to detect the role of mental disorder.

It is conceivable that there was a peak in the 1970s of incidence of severe and enduring mental illness. Rates of schizophrenia are probably not as stable as was once believed Reference Saha, Chant and McGrath21 or it may be that a particular combination of mental illness and patterns of drug misuse may have resulted in a peak in homicides due to mental disorder. However, neither of these hypotheses is supported by substantial empirical evidence.

There may be separate explanations for the rise and the subsequent fall in homicide due to mental disorder. First, it is likely that rates of abnormal homicide increased because of the same sociological factors (e.g. the availability of weapons, patterns of substance misuse, and patterns of internal and external migration) that caused the increase in total homicide. This is consistent with the finding that regions with a high total homicide rate also have larger numbers of homicides by people who are mentally ill Reference Boudouris9–Reference Evans and Malesu11 and by those with schizophrenia. Reference Boudouris9,Reference Wilcox10

Effect of treatment on homicide rates

The subsequent fall may well be due to improvements in treatment. The introduction and increasing use of antipsychotic medication, the greater awareness of the treatment of psychosis by primary care providers after deinstitutionalisation, and the creation of regional health authorities with responsibility for defined populations, may have all contributed to the observed decline in abnormal homicide since the 1970s. This is consistent with the findings of recent studies in the UK and Australia, which suggest that initial treatment of psychosis may reduce the risk of homicide. Reference Meehan, Flynn, Hunt, Robinson, Bickley, Parsons, Amos, Kapur, Appleby and Shaw22–Reference Large and Nielssen24 The finding that the decline in abnormal homicide is due to better treatment is supported by a recently published study showing a parallel rise and fall in suicide rates, particularly among younger men. Reference Simpson, McKenna, Moskowitz, Skipworth and Barry-Walsh5 Treatment is a better explanation than limitation of lethal means because treatment of the mentally ill would not be expected to significantly reduce total homicides, and reduction in the availability of lethal means would be likely to reduce total homicides.

Regardless of the reason for the change, the main finding of this study is that rates of homicide due to mental disorder are not fixed. This finding counteracts previous views about the potential to reduce this form of homicide Reference Coid3,Reference Taylor and Gunn4 and should encourage further research to examine the causes of homicides by the mentally ill, which in turn could inform clinical practice and save lives.

Appendix

Types of homicide due to mental disorder Reference Taylor and Gunn4

| Legal outcome | Approximate definition |

| Not guilty by reason of insanity | At the time of the commission of the acts constituting the offence, the defendant, as a result of a severe mental disease or defect, was unable to appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of his acts. |

| Diminished responsibility | Where a person kills or is a party to the killing of another, he shall not be convicted of murder if he was suffering from such an abnormality of mind (whether arising from a condition of arrested or retarded development of mind or any inherent causes or induced by disease or injury) as substantially impairing his mental responsibility for his acts and omission in doing or being party to the killing. |

| Unfit to plead | Where the accused is unable to understand the charge and possible penalties, or unable to understand court proceedings, or unable to give instructions to a defence lawyer. |

| Infanticide | When a woman or girl who unlawfully kills her child (under 12 months) under circumstances which, but for this section, would constitute wilful murder or murder, does the act which causes death when the balance of her mind is disturbed because she is not fully recovered from the effect of giving birth to the child or because of the effect of lactation consequent upon the birth of the child, she is guilty of infanticide only. |

| Homicide—suicide | When the homicide offender completes a suicide at the same time or after the homicide. Most suicides after homicide occur within a week of the homicide and suicides that occur after a conviction are not included in official statistics. It is not known what proportion of homicide—suicide offenders might have had a mental illness defence available to them had they survived. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank J. Kenny-Herbert of the Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Trust and Professor R. Mackay of De Montfort University for their helpful comments on the subject matter.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.