The 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), released by the World Health Organization in May 2019, officially came into effect in 35 countries around the globe in 2022.1 Along with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), ICD-11 serves as a global standard for the taxonomy and diagnosis of mental illnesses. The latest major revision of DSM (DSM-5)2 was released a decade ago and ever since its release, anticipation regarding to what extent ICD would follow or depart from its counterpart has grown. We briefly examine this question with respect to the classification of bipolar disorder, as this has been the subject of intense debate and it serves as an exemplar of what harmonisation of taxonomies means for clinical practice. Interestingly, analogous to the bipolar nature of the illness, ICD-11 shows progress but has also made some omissions, which we argue will have a negative impact on both research and clinical practice as well as people living with bipolar disorder.

One step forward …

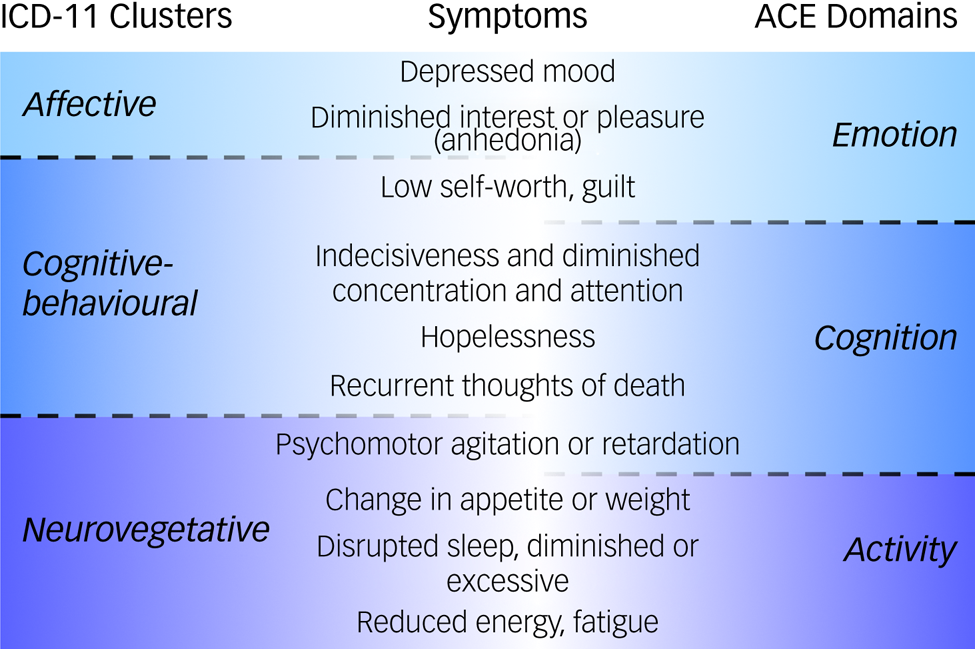

First, ICD-11 has made some promising progress. It has introduced a model for classifying depressive symptoms according to ‘clusters’ of affective, cognitive–behavioural and neurovegetative symptoms. These clusters broadly align with the symptom domains of the ACE (activity, cognition and emotion) model of mood disorders (Fig. 1), which is based on Kraepelin and Weygandt's conception of will (volition), thoughts and feelings.Reference Malhi, Irwin, Hamilton, Morris, Boyce and Mulder3

Fig. 1 Symptoms of depression according to clusters in ICD-11 and domains in the ACE (activity, cognition and emotion) model.Reference Malhi, Irwin, Hamilton, Morris, Boyce and Mulder3

Shaded sections indicate the symptom cluster to which each symptom belongs within the ICD-11 taxonomy (affective is denoted by light blue, cognitive–behavioural by middle blue and neurovegetative by dark blue) and the ACE model (emotion is denoted by light blue, cognition by middle blue, activity by dark blue). Note that irritability is an important transdiagnostic symptom that is diagnostic of mania and features strongly in depression in young people but is not captured specifically in either of the main classificatory schema for depression in adults.

The ACE classification of depressive symptoms is an important advance in the conceptualisation of mood disorders and the use of diagnoses in clinical practice. This is because understanding the functional domains that are affected by a depressive episode in an individual allows for more precise tailoring of treatments and more granular tracking of clinical changes over time. For this reason, the ACE model was included in recent binational guidelines,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell4 which have since gained widespread recognition.

Two steps back

In contrast to the sophistication introduced into the classification of depressive episodes (clearly a step forward), simultaneously ICD-11 has taken two steps back.

First, after 30 years of research since ICD-10, the symptomatic characterisation of manic episodes remains much the same. Puzzlingly, the clustering of symptoms used to subdivide and refine the depressive syndrome has not been extended to mania, despite manic symptoms readily fitting the affective, cognitive–behavioural and neurovegetative labels. Indeed, the ACE model for mood disorders can be used to group all the symptoms of bipolar disorder (i.e. both depressive and manic symptoms). This is because the spectrum of symptoms of both depression and mania are simply extremes of more continuous dimensional changes. Using a classification based purely on polar opposites (e.g. diminished and heightened sleep, energy and pleasure respectively) and ignoring any intermediate states fails to capture the clinical complexity of real-world phenotypes.

Another important omission is that ICD-11 has provided no means of capturing unipolar mania, namely manic symptoms that occur in the absence of any depressive episodes. This means that this entity cannot be diagnosed and therefore will not be counted in future epidemiological research. Instead, such presentations of mania will automatically be subsumed within bipolar disorder. In other words, clinicians can diagnose depression on its own, and depression occurring in conjunction with mania automatically becomes part of bipolar disorder, but mania on its own has no distinct status and is considered the same as bipolar disorder. This asymmetry is common to both ICD-11 and DSM-5.

But surely the publication of ICD-11 nearly three decades after ICD-10, and almost a decade after DSM-5, was an opportunity to make improvements rather than recreate a previously flawed conceptualisation. However, an argument often put forward in defence of the adopted approach is the need to harmonise the two taxonomies.Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell4 This would perhaps be acceptable if the classification being emulated had achieved optimal accuracy, but it hasn't. Further, harmonisation alone should not be the dominant driver of nosology, especially if the data argue against it, and the two systems of classification have distinct histories and objectives. Indeed, the contested nature of diagnosis per se and the contrasts between the two systems reflect underlying contradictions. Yet, some contrasts are promoted: for example, dimensions and clusters have been introduced to describe depression in ICD-11, even though this is not in keeping with the approach used by DSM-5.

A second step back concerns the arbitrary separation of hypomania and mania, and thereby the subtyping of bipolar disorder. Once again, with a view to following DSM-5's lead, ICD-11 has partitioned mania and given credence to the existence of subtypes of bipolar disorder – specifically, bipolar I and II. Within the diagnostic criteria for hypomania, the only criteria that distinguish hypomania from mania are the duration and severity of symptoms. Thus, ICD-11 acknowledges that there is no real difference in kind between hypomania and mania, and that the term hypomania is essentially used to mean less severe mania. This again highlights the classificatory inconsistencies in ICD-11 as regards depressive and manic symptomatology. For instance, although depression is considered a dimensional construct with respect to severity, there is no subtype of hypodepression to describe less severe forms of depressive disorders. In contrast, mania is partitioned arbitrarily on the basis of severity, instead of the clustering of symptoms into domains as applied to depression, which arguably would have provided greater specificity.

These inconsistencies are first confusing, especially when both mood states (mania and depression) appear in the same disorder, and second illogical, as there seems to be no cogent argument as to why mania is split according to severity but depression is not. Further, the inclusion of bipolar II disorder in ICD-11 does not advance our understanding of mood disorders and does not meaningfully inform clinical management.

Finally, although ICD attempts to demarcate hypomania from mania, it does not clearly define its boundary with normality, and indeed puts fewer restrictions on diagnosing hypomania than DSM-5.Reference Angst, Ajdacic-Gross and Rössler5 At the same time, the occurrence of hypomania in the absence of a history of other types of mood episode is insufficient to warrant an independent mood disorder diagnosis. This curious state of affairs further weakens both the theoretical argument for subtyping bipolar presentations and the clinical value of assigning a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder.

Conclusions

As each season comes and goes, shops advertising their wares often change what they present in their windows. Such window dressing is important, because it informs people of what is new and what has changed, even though much of what is in the store usually remains the same. In a similar vein, it seems ICD-11 has attempted to present itself anew, but closer inspection reveals that it is not meaningfully different from previous versions. The desire to harmonise the two major taxonomies has some basic logic, but it seems that ICD-11 has overlooked the groundswell change that has occurred in the past few decades – with greater importance now being attached to personalised and evidence-based medicines, and the need to tailor treatments and accommodate the vast array of new therapies that have become available.

Modern-day sophisticated management of mood disorders requires that the very first step, that of diagnosis, is the most sure-footed. To this end, there is a need for a precise taxonomy that reflects reality. This requires incorporating our understanding from research and faithfully capturing the many clinical nuances of mood disorders. There is evidence of this thinking in ICD-11's approach to depressive disorders, but why this has not been extended to mania is baffling. Similarly, the greater understanding and appreciation of mixed states that has been achieved in recent years seems to have been overlooked, with only minor changes incorporated into ICD-11, again presumably to keep in line with DSM-5. However, the latter (DSM) is mainly used for research and insurance-funded rebates, especially in North America, whereas ICD is more widely used across the world for making diagnoses in clinical practice. Therefore, harmonisation of the two taxonomies may be unhelpful.

Thus, we propose that the classification of mood disorders in ICD-11 be further revised, with the specific aim of producing a taxonomy that reflects clinical reality and is consistent in its approach across the full spectrum of mood disorders. This can be achieved by (a) extending to mania and mixed mood states the symptom clusters approach; (b) recognising unipolar mania as a distinct clinical entity; and (c) applying to mania the same dimensional perspective that has been used for depression.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contribution

G.S.M. and E.B. researched the article and produced the original draft and figures. K.B. edited the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

G.S.M. is a Deputy Editor of BJPsych and has received grant or research support from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Rotary Health, NSW Health, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Ramsay Research and Teaching Fund, Elsevier, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Servier; and has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Servier. K.B. is Editor-in-Chief of BJPsych. G.S.M. and K.B. did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.