The deinstitutionalisation of psychiatric care in high-income countries has increased the number of people being cared for in the community. Reference Thornicroft and Tansella1,Reference Magliano, Fadden, Madianos, de Almeida, Held and Guarneri2 People caring for adults with schizophrenia spend an average of 6–9 h per day providing care. Reference Roick, Heider, Bebbington, Angermeyer, Azorin and Brugha3 In the UK data suggest that 15% of those caring informally for people with schizophrenia spend 9–32 contact hours per week providing care and 43% spend over 32 h per week. Reference Andrew, Knapp, McCrone, Parsonage and Trachtenberg4 Many people are unable to work or have to take time off work to provide care. The informal unpaid care they provide saves the National Health Servcie (NHS) the cost of providing comparable paid care, which is approximately £34 000 per person with schizophrenia (calculated using a mean of 5–6 h per day). Reference Commission5 Families who take on the responsibility of caring for a relative with schizophrenia save the public £1.24 billion a year. Reference Nolan and Lundh6 Caring can be a strongly positive experience, Reference Awad and Voruganti7 but it is often associated with burdens that are subjective (perceived) and objective (for example, contributing directly to ill health and financial problems or in displacing other daily routines). Reference Raune, Kuipers and Bebbington8 Other reported negative consequences of caring for those with psychosis include poor satisfaction with services provided, and difficulties in coping. Reference Kuipers9 Many interventions for those with serious mental health problems provided by health and social care services are focused on the person using the service. Even when family interventions are offered to people with severe mental illness and their families, the number of sessions that specifically include the carer varies, and clinical staff typically do not see it as ‘their job’ to offer direct help to carers. Reference Chien and Wong10 However, it is well established that the burden of care and ability of a carer to cope can have an impact on the recovery of the patient. Reference Kuipers, Onwumere and Bebbington11,Reference Pharoah, Mari, Rathbone and Wong12 Family interventions for people with severe mental illness may reduce relapse rates and increase cooperation with pharmacotherapy, Reference Jeppesen, Petersen, Thorup, Abel, Oehlenschlaeger and Christensen13 and the burden of care may be reduced by psychosocial interventions, Reference Magliano, Fiorillo, Malangone, De Rosa and Maj14,Reference Chien and Norman15 but the specific effects of interventions for carers themselves are not usually reported or are seen as secondary outcomes.

A number of reviews have evaluated published research on interventions for people caring for someone with serious mental illness, such as mutual support and interventions delivered by community mental health nurses. Chien & Norman surmised that although it is recognised that mutual support has a beneficial effect on outcomes both for people with severe mental illness and for their families, further research is required to evaluate the effects of mutual support on the carers themselves. Reference Macleod, Elliott and Brown16 The review by Macleod et al of nurse-delivered interventions for carers reported that support and education interventions, community outreach programmes and mutual support all had beneficial effects on carer burden. Reference Lobban, Postlethwaite, Glentworth, Pinfold, Wainwright and Dunn17 A recent systematic review assessed the effectiveness of family interventions on relatives of people with psychosis, Reference Higgins and Green18 but did not include a meta-analysis. The aim of our review was to investigate interventions provided by health and social care services for people caring for someone with severe mental illness. This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions with the primary goal of improving carers’ experience and reducing carer burden. The review was not registered.

Method

We conducted a systematic review of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) to evaluate interventions delivered by health and social care services to the carers of people with severe mental illness (schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders). We therefore excluded studies in which more than a third of the study population cared for a person with major depression or a common mental health disorder. Carers were defined as family or friends who provided informal and regular care and support to someone with severe mental illness. Interventions were included if they were provided to the carer alone (i.e. without the patient present) and if the content of the intervention had the aim of improving the carer’s experience of care and reducing carer burden. Studies were included if they evaluated interventions aimed at improving the experience of caregiving. We excluded studies that were limited to the provision of financial and day-to-day practical support (for example personal assistance or direct payments) or to interventions targeted at the patient rather than the carer.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of the review was the experience of caregiving, involving positive and negative experiences of caring for someone with severe mental illness. Secondary outcomes were carer quality of life, satisfaction with services and psychological distress. Only data from validated outcome measures were included in the meta-analysis. Outcome data were grouped by the following time points: end of intervention, up to 6-month follow-up and longer than 6-month follow-up. For outcomes measured at several time points within these intervals, we selected the longest follow-up point following randomisation.

Search strategy

We conducted a search for RCTs published from the inception of databases up to June 2013 with no language restrictions (see online Appendix DS1). The following databases were searched: CENTRAL, CDSR, DARE, HTA, EMBASE, Medline, Medline In-Process, AEI, ASSIA, BEI, CINAHL, ERIC, IBSS, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts and SSA. Reference lists from previous reviews and included studies were examined and study authors were contacted. Titles and abstracts were screened based on the review protocol by one author (B.H.) and reviewed by another author (A.Y.-U.). Full texts of studies meeting inclusion criteria were then retrieved and reviewed to further establish inclusion in the review. Any disagreements were discussed with a third author (E.M.-W.) until a consensus was reached.

Data management

Following Cochrane Collaboration methods, data were extracted independently by two reviewers (A.Y.-U. and B.H.). We extracted data for study characteristics (setting, number randomised and duration), inclusion criteria, carer and patient demographics, characteristics of the interventions (content, frequency and duration, contextual information) and outcomes. Authors were contacted to request missing participant characteristics and outcome data, and to enquire about unpublished studies.

Assessment of bias

We assessed each study using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool, Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Akl, Kunz, Vist and Brozek19 and judged whether each study was at low, high or unclear risk of bias for specified domains. Each study was rated for risk of bias due to sequence generation; allocation concealment; masking of participants, assessors and providers; selective outcome reporting; and incomplete data. Studies were independently assessed by two authors (A.Y.-U., B.H.), and disagreements were discussed with a third author (E.M.-W.). Authors of included studies were contacted to supply any unreported information such as outcomes or study methods. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to assess the quality of the evidence for each outcome. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman20 This approach uses a structured method of assessing the overall quality of each outcome into one of four GRADE ratings (high, moderate, low and very low) based on an assessment of five factors: limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias (www.gradeworkinggroup.org). Where more than ten trials were included in a meta-analysis, publication bias was assessed using funnel plots.

Statistical analysis

Where possible data were entered directly into Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.2 for Windows. For dichotomous outcomes we calculated relative risks (RRs) or rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals using Mantel-Haenszel methods. For continuous outcomes, standardised mean differences (SMDs) and 95% CIs were calculated using Hedges’ g and combined using inverse variance methods. We used random-effect methods for all meta-analyses. When studies reported data in multiple formats we calculated the SMD and its standard error before entering data in RevMan. Effect estimates favour intervention (i.e. carer intervention rather than control) when the relative risk is reduced (RR<1) or the standardised difference is negative (SMD<0). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by visual inspection of forest plots, by the test (assessing P value) and by calculating the I 2 statistic, which describes the percentage of observed heterogeneity that would not be expected by chance. Reference Cheng and Chan21 If P was less than 0.10 and I 2 exceeded 40%, we considered heterogeneity to be substantial. In these cases we explored the possible reasons for heterogeneity which included sensitivity analysis with and without studies that were causing the heterogeneity. When subgroup analyses were conducted, differences between groups were tested using within RevMan. To assess the possibility of small study bias, random-effects estimates were compared with fixed-effect estimates. Data were analysed and presented first as intervention v. control (e.g. treatment as usual, active control, waiting list, no treatment), followed by direct comparisons of carer interventions. We conducted a planned subgroup analysis on the basis of the diagnosis of the patient; these analyses were conducted and reported dependent on data availability.

Results

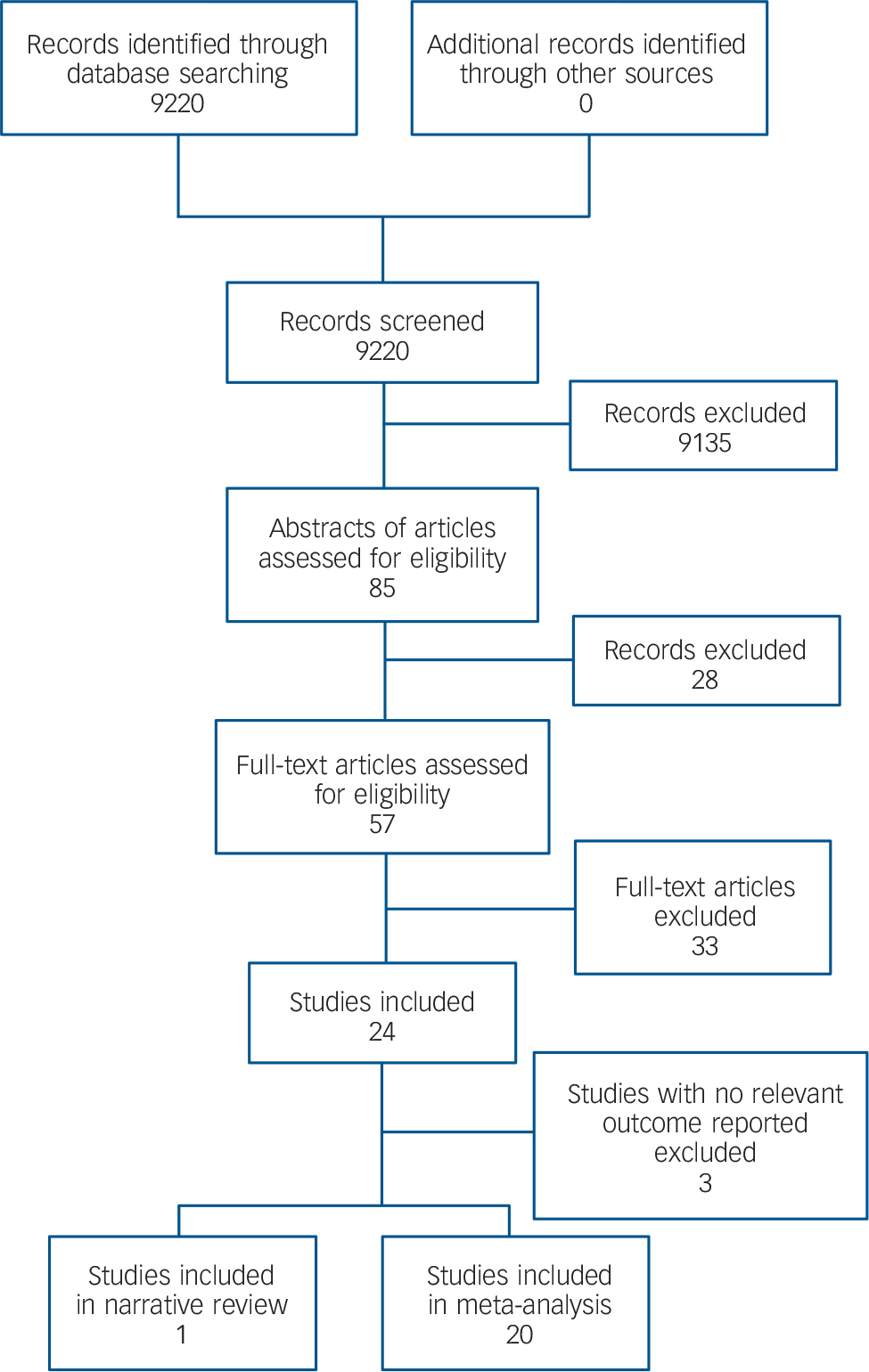

From 9220 records 24 studies met inclusion criteria for the review; of these, 20 studies were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Three studies did not report any eligible outcome and were thus excluded. One study did include relevant outcomes but did not report sufficient data in a format that could be used for meta-analysis. The findings from this study are described narratively. All included studies were published in English. Reasons for excluding 33 studies are summarised in online Table DS1. Two ongoing studies were identified (Table DS1).

Description of studies

Studies assigned 1589 carers with a median sample size of 63, ranging from 40 to 225 (Table 1). Reference Chien and Chan22–Reference Szmukler, Burgess, Herrman, Bloch, Benson and Colusa42 The 20 studies included in meta-analyses randomised 1364 carers (86% of people included in the review). Comparisons included treatment as usual/control compared with psychoeducation, Reference Chien and Chan22,Reference Chien, Norman and Thompson35 a support group, Reference Chien and Wong23,Reference Chien, Thompson and Norman36–Reference McCann, Lubman, Cotton, Murphy, Crisp and Catania38 a combined psychoeducation and support group, Reference Chien, Norman and Thompson35 problem-solving

Fig. 1 Study selection.

bibliotherapy, Reference Lobban, Glentworth, Chapman, Wainwright, Postlethwaite and Dunn39 and self-management. Reference Perlick, Miklowitz, Lopez, Chou, Kalvin and Adzhiashvili40 One study compared enhanced psychoeducation with standard psychoeducation, Reference Smith and Birchwood41 and one study compared psychoeducation delivered by post with practitioner-delivered psychoeducation. Reference Szmukler, Burgess, Herrman, Bloch, Benson and Colusa42 Two of the included studies were three-arm studies comparing two active interventions with treatment as usual, Reference Chien and Wong23,Reference Chien, Norman and Thompson35 and are therefore included in multiple comparisons. One study included a group evaluating an intervention termed ‘psychotherapy’; Reference Posner, Wilson, Kral, Lander and McIlwraith28 however, this arm was not included in our review because it did not meet the eligibility criteria outlined above. Experience of caregiving was measured using the Experience of Caregiving Inventory, Reference Pai and Kapur43 the Family Burden Interview Schedule, Reference Platt, Weyman, Hirsch and Hewett44 the Social Behaviour Assessment Schedule, Reference Malakouti, Nojomi, Panaghi, Chimeh, Mottaghipour and Joghatai45 the Family Burden Questionnaire, Reference McDonell, Short, Berry and Dyck46 and the Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale. Reference Larsen, Attkisson, Hargreaves and Nguyen47 Carer quality of life was measured using the 12-item and 36-item Short Form Health Surveys (SF-12 and SF-36) and satisfaction with services was measured using the Consumer Satisfaction Questionnaire. Reference Goldberg and Blackwell48 Finally, psychological distress was measured using the 12-item and 28-item General Health Questionnaires, Reference Kellner and Sheffield49 the Symptom Rating Test, Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh50 the Beck Depression Inventory, Reference Kessler, Andrews, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek and Normand51 the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, Reference Lewis, Pelosi, Araya and Dunn52 and the Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised. 53 For a summary of the components of the interventions provided in the included studies, see online Table DS2.

Seven studies were conducted in China, four in the UK, two in the USA, two in Australia, two in Iran, one in Canada, one in Spain, one in Chile and one in Ireland. The median of the mean age of carers was 49 years, and the median study included 76% women. The median percentage of carers living with patients was 100% (range 49–100); however, this was not reported in six studies. The diagnoses of the patients varied across studies: 16 studies included people with diagnoses of psychosis or schizophrenia spectrum disorder and 3 included people with bipolar disorder. Of the remaining two mixed population studies, the majority of patients had a diagnosis of psychosis and schizophrenia (Table 1).

Quality of included studies

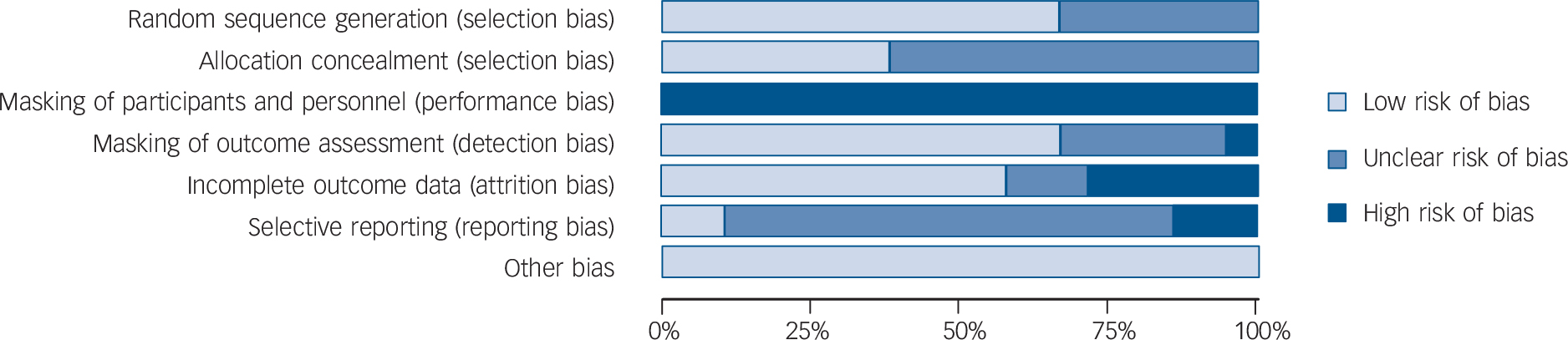

Sequence generation was adequately described in 14 studies and unclear in 7 studies (Fig. 2, online Fig. DS1). There was low risk of bias for allocation concealment in 8 studies but this was unclear for 13 studies. Masking of participants and personnel was not possible; all studies were at high risk of bias per se. For masking of outcome assessment, 14 studies were at low risk of bias, 1 was at high risk of bias and 6 were unclear. At the study level, 12 studies were at low risk of bias for missing data, 6 studies were at high risk of bias and 3 studies were unclear. We were able to confirm by contacting trial authors and checking review protocols that 2 studies were completely free of selective outcome reporting (i.e. clearly reported all outcomes measured). However, 16 studies were at unclear risk of selective outcome reporting and 3 were at high risk. Overall, the primary outcome was measured in a variety of ways (both within and between studies) and follow-up data beyond the end of the intervention were inconsistent. Therefore, there is a high possibility of selective reporting in this review.

Effects of interventions

The results of the meta-analysis of prespecified outcomes are summarised in online Table DS3.

Psychoeducation v. any control

Eight studies with 428 participants were included in the analysis of the experience of caregiving assessed at the end of the intervention. Reference Chien and Chan22,Reference Gutierrez-Maldonado and Caqueo-Urizar24–Reference Leavey, Gulamhussein, Papadopoulos, Johnson-Sabine, Blizard and King26,Reference Sharif, Shaygan and Mani30–Reference Solomon, Draine, Mannion and Meisel32,Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese and Maphosa34 There was very low-quality evidence of a large effect of psychoeducation on experience of caregiving. Four studies with 215 participants provided data up to 6-month follow-up. Reference Chien and Wong23,Reference Leavey, Gulamhussein, Papadopoulos, Johnson-Sabine, Blizard and King26,Reference So, Chen, Chan, Wong, Hung and Chung31,Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese and Maphosa34 There was very low-quality evidence of a large effect on the experience of caregiving. Three studies including 151 participants reported very low-quality evidence of a large effect of the intervention on the experience of caregiving at greater than 6-month follow-up. Reference Chien and Wong23,Reference Gutierrez-Maldonado and Caqueo-Urizar24,Reference Posner, Wilson, Kral, Lander and McIlwraith28 However, despite large effect sizes being reported for the experience of caregiving at all end of treatment and follow-up assessments, heterogeneity was very high (I = 89%, 79% and 86% respectively) so interpretation of results should be done cautiously. Sensitivity analysis did not explain the possible reason for the high heterogeneity. However, inspection of the forest plots shows that the direction of effect is consistent across studies and the high heterogeneity may have been caused by differences in the magnitude of effects across studies. See online Figs DS2–4 for the corresponding forest plots.

One study including 44 participants found low-quality evidence of no significant difference between psychoeducation and control in quality of life at the end of the intervention. Reference Koolaee and Etemadi25 One study with 39 participants found low-quality evidence of no significant difference between the intervention and control in satisfaction with services at either the end of the intervention or up to 6-month follow-up. Reference Reinares, Vieta, Colom, Martinez-Aran, Torrent and Comes29 Two studies with 86 participants were included in the analysis of carer psychological distress; Reference Reinares, Vieta, Colom, Martinez-Aran, Torrent and Comes29,Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese and Maphosa34 there was very low-quality evidence of no difference between the intervention and control at the end of the intervention. Similarly, there was low-quality evidence of no difference between the groups up to 6-month follow-up. However, one study with

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies, categorised by intervention

| Study | Country | Sample

size (n) |

Mean age (years) |

Gender, female (%) |

Living with patient (%) |

Patient diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychoeducation v. any control | ||||||

| Cheng & Chan (2005) Reference Chien and Chan22 | China | 64 | NR | 63 | NR | SSD |

| Chien & Wong (2007) Reference Gutierrez-Maldonado and Caqueo-Urizar24 | China | 84 | 41 | 67 | 100 | SSD |

| Gutierrez-Maldonado & Caqueo-Urizar (2007) Reference Koolaee and Etemadi25 | Chile | 45 | 54 | 76 | NR | SSD |

| Koolaee & Etemadi (2009) Reference Leavey, Gulamhussein, Papadopoulos, Johnson-Sabine, Blizard and King26 | Iran | 62 | 55 | 100 | 100 | SSD |

| Leavey et al (2004) Reference Madigan, Egan, Brennan, Hill, Maguire and Horgan27 | UK | 106 | NR | NR | 54 | SMI |

| Madigan et al (2012) Reference Posner, Wilson, Kral, Lander and McIlwraith28 | Ireland | 47 | 52 | 53 | 55 | BPD |

| Posnor et al (1992) Reference Reinares, Vieta, Colom, Martinez-Aran, Torrent and Comes29 | Canada | 55 | NR | NR | 58 | SSD |

| Reinares et al (2004) Reference Sharif, Shaygan and Mani30 | Spain | 45 | 48 | 76 | 100 | BPD |

| Sharif et al (2012) Reference So, Chen, Chan, Wong, Hung and Chung31 | Iran | 70 | 52 | NR | NR | SSD |

| So et al (2006) Reference Solomon, Draine, Mannion and Meisel32 | China | 45 | 49 | 78 | 100 | SSD |

| Solomon et al (1996) Reference Szmukler, Herrman, Colusa, Benson and Bloch33,Footnote a | USA | 225 | 56 | 88 | 84 | SMI |

| Szmukler et al (1996) Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese and Maphosa34 | Australia | 63 | 46 | NR | 68 | SSD |

| Szmukler et al (2003) Reference Chien, Norman and Thompson35 | UK | 61 | 54 | 82 | 49 | SMI |

| Support group v. any control | ||||||

| Chien et al (2004) Reference Chien, Thompson and Norman36 | China | 48 | 44 | 56 | 100 | SSD |

| Chien & Chan (2004) Reference Chien and Wong23 | China | 96 | 42 | 31 | 100 | SSD |

| Chien et al (2008) Reference Chou, Liu and Chu37 | China | 76 | 36 | 55 | 100 | SSD |

| Chou et al (2002) Reference McCann, Lubman, Cotton, Murphy, Crisp and Catania38 | China | 84 | NR | 66 | NR | SSD |

| Psychoeducation plus support group v. any control | ||||||

| Szmukler et al (2003) Reference Chien, Norman and Thompson35 | UK | 61 | 54 | 82 | 49 | SMI |

| Problem-solving bibliotherapy v. any control | ||||||

| McCann et al (2012) Reference Lobban, Glentworth, Chapman, Wainwright, Postlethwaite and Dunn39 | Australia | 124 | 47 | 82 | 82 | Psychosis |

| Self-management v. any control | ||||||

| Lobban et al (2013)40 | UK | 103 | NR | 83 | 73 | Psychosis |

| Enhanced psychoeducation v. standard psychoeducation | ||||||

| Perlick et al (2010) Reference Smith and Birchwood41 | USA | 46 | 53 | 84 | 65 | BPD |

| Practitioner-delivered v. postal psychoeducation | ||||||

| Smith & Birchwood (1987) Reference Szmukler, Burgess, Herrman, Bloch, Benson and Colusa42 | UK | 40 | NR | NR | NR | SSD |

BPD, bipolar disorder; NR, not reported; SMI, serious mental illness or mood disorder; SSD, schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

a. Not included in meta-analysis.

18 participants provided data at over 6-month follow-up showing moderate quality of a large effect of psychoeducation over control on psychological distress. Reference Posner, Wilson, Kral, Lander and McIlwraith28

One study of participants receiving individual psychoeducation found the intervention less helpful than group psychoeducation for understanding of medication (= 8.39, d.f. = 1, P<0.004). Reference Szmukler, Herrman, Colusa, Benson and Bloch33 Furthermore, those receiving the group psychoeducation intervention found the sessions less useful than participants in the individual psychoeducation group for learning about the community resources available to them (= 8.69, d.f. = 1, P<0.004).

Support group v. any control

Three studies including 194 participants provided very low evidence of a large effect on the experience of caregiving at the end of the intervention. Reference Chien, Thompson and Norman36–Reference McCann, Lubman, Cotton, Murphy, Crisp and Catania38 There was low-quality evidence of a moderate effect at up to 6-month follow-up. However, although a clinically large effect was observed, this effect was no longer

Fig. 2 Risk of bias summary.

statistically significant at more than 6-month follow-up. However, although the studies included in the analysis at end of intervention and greater than 6-month follow-up showed large effects favouring support groups, heterogeneity was very high (I = 85% and I = 96% respectively). The direction of the effect consistently favoured the intervention and sensitivity analysis showed that high heterogeneity was possibly caused by difference in the magnitude of effect across included studies. One study with 70 participants provided low-quality evidence of a large effect of support groups on psychological distress at the end of the intervention and up to 6-month follow-up. Reference McCann, Lubman, Cotton, Murphy, Crisp and Catania38 See online Figs DS5–7 for the corresponding forest plots.

Psychoeducation plus support group v. any control

One study contributing 49 participants provided low-quality evidence of no effect of psychoeducation plus support group on the experience of caregiving at over 6-month follow-up; Reference Chien, Norman and Thompson35 data were only available for a psychosis and schizophrenia spectrum disorder sample (see online Fig. DS8 for the corresponding forest plot). The same study provided low-quality evidence of no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups on psychological distress at over 6-month follow-up. Reference Chien, Norman and Thompson35

Problem-solving bibliotherapy v. any control

One study including 114 participants provided low-quality evidence of no effect of problem-solving bibliotherapy on the experience of caregiving at the end of the intervention, Reference Lobban, Glentworth, Chapman, Wainwright, Postlethwaite and Dunn39 and of no statistically significant effect at 6-month follow-up. Data were only available for a psychosis and schizophrenia spectrum disorder sample (see online Figs DS9 and DS10 for the corresponding forest plots). This study provided low-quality evidence of no clinically meaningful difference between intervention and control groups in quality of life at the end of the intervention, Reference Lobban, Glentworth, Chapman, Wainwright, Postlethwaite and Dunn39 but moderate benefit was observed up to 6-month follow-up. There was moderate-quality evidence of a large effect of the intervention on psychological distress at the end of the intervention and up to 6 months later. Reference Lobban, Glentworth, Chapman, Wainwright, Postlethwaite and Dunn39

Self-management v. any control

One study with 86 participants provided moderate-quality evidence of no effect on self-management on either the experience of caregiving or psychological distress at the end of the intervention. Reference Perlick, Miklowitz, Lopez, Chou, Kalvin and Adzhiashvili40 Data were available only for a mixed severe mental illness sample (see online Fig. DS11 for the corresponding forest plots).

Enhanced v. standard psychoeducation

One study, contributing 43 participants to the review, provided moderate-quality evidence that enhanced psychoeducation had a moderate effect on the experience of caregiving when compared with standard psychoeducation at the end of the intervention. Reference Smith and Birchwood41 Data were available from only a single study including a bipolar disorder sample (see online Fig. DS12 for the corresponding forest plot).

Practitioner-delivered v. postal psychoeducation

One study with 40 participants provided low-quality evidence that practitioner-delivered psychoeducation was no more effective than postal psychoeducation for either family distress or psychological distress at the end of the intervention and at up to 6-month follow-up. Reference Szmukler, Burgess, Herrman, Bloch, Benson and Colusa42

Subgroup analysis

A test for difference based on the diagnosis of the patient could only be conducted for the psychoeducation intervention compared with control. All other comparisons included only carers for people with psychosis or schizophrenia and thus no subanalysis was possible. Subgroup data for psychoeducation compared with control was available only for the outcome of experience of caregiving at the end of the intervention and greater than 6-month follow-up. However, the bipolar disorder subgroup accounted for only 11% of the participant data included in this analysis and thus subanalysis based on diagnosis was unlikely to be meaningful.

Discussion

This is the first formal systematic review and meta-analysis of carer-focused interventions for people caring for someone with severe mental illness, and despite shortcomings in the underpinning evidence it suggests that psychosocial interventions specifically aimed at helping carers can lead to both improvements in the experience of caregiving and quality of life, and decreases in burden and psychological distress. The findings of this review are consistent with previous reviews in finding that education and support may be beneficial to those caring for people with severe mental illness. Reference Macleod, Elliott and Brown16–Reference Higgins and Green18 Although most evidence in this review comes from studies of psychoeducation and support groups, with most other interventions evaluated in single studies (often with small numbers of participants), it was not possible to identify with certainty which specific intervention was superior. The evidence is derived from studies of those caring for people with severe mental illness, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders, psychosis, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and there is growing evidence that providing these interventions early (in the first episode of psychosis) has benefits for carers.

Strengths and limitations

The limitations of this data-set are substantial. First, the quality of the evidence underpinning critical outcomes in this meta-analysis was very low to moderate. For example, in studies of psychoeducation the experience of caregiving had a large effect size derived from four studies of reasonable size, but the quality was downgraded to ‘very low’ owing to a high risk of bias, significant heterogeneity and a lack of precision. Data on support groups also showed high levels of heterogeneity. It is possible that for both psychoeducation and support groups for carers, the interventions pooled in the analysis had some important differences leading to heterogeneity. Moreover, we sought to combine outcomes across studies, but there was only evidence from one trial for some outcomes and meta-analysis was not always possible. Given the small number of studies and participants, important effects may be statistically insignificant because the analyses lack power, or they may be overestimated by chance or by small study bias. We have reported all results to maximise the transparency and completeness of the review, but many results are limited by the lack of replication, imprecision and risk of reporting bias. Most measures in this review sought to assess subjective, participant-reported outcomes. Compared with objective outcomes, these measures may be associated with more error and greater risk of bias (e.g. response bias). Despite these limitations and variations in effect sizes, the critical outcomes for both psychoeducation and support groups were consistently positive and provide qualified evidence of benefit.

The range of conditions represented in the study populations may have contributed to heterogeneity, but may also have contributed to the external validity of our results. Studies included those caring for people with schizophrenia and other schizophrenia spectrum disorders, first-episode psychosis and bipolar disorder. It is possible that this variation contributed to statistical heterogeneity in the meta-analyses. Although the majority of the evidence relates to carers of people with psychosis, carers of people with other conditions face similar difficulties and challenges, and this evidence may suggest that interventions for carers could be beneficial for a number of populations. Finally, our review of support groups included studies conducted only in East Asian populations, with healthcare settings and practices likely to be substantially different from those found in other countries, thus limiting generalisability. Nevertheless, a variety of countries were represented in the wider review, suggesting consistently beneficial effects across different countries, and we can surmise that support groups are likely to be better than nothing for carers. Indeed, this finding, and those for psychoeducation, confirm the results of systematic literature reviews of interventions for carers, Reference Macleod, Elliott and Brown16,Reference Lobban, Postlethwaite, Glentworth, Pinfold, Wainwright and Dunn17 and of a systematic review of outcomes for carers in studies of interventions for patients. Reference Higgins and Green18

Implications for practice

The interventions evaluated in this review are themselves complex, and there is a clear argument that a focus on those in a caring role will be beneficial both for them and for patients. Although this review cannot recommend any specific intervention, it does raise the importance of assessing the experience of caregiving, levels of burden and psychological distress, and the quality of life of people caring for someone with severe mental illness, including psychosis, in routine practice. The sometimes substantial improvements in critical outcomes shown in a number of quite varied studies can (at least in part) be taken as evidence of an underlying need that carers have for help, not just as caregivers but as individuals. This supports the view that those caring for someone with severe mental illness would benefit from help and interventions focused on their own needs as an additional component of healthcare service provision for patients supported by carers in the community. Reference Chien and Wong10 Clearly, if a carer assessment suggests that a carer needs help, whether this is to enhance caregiving or to reduce psychological distress and improve quality of life, carer-focused interventions should be considered. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on psychosis and schizophrenia recommends that all people with psychosis or schizophrenia, including people with first-episode psychosis, should be routinely offered family interventions to promote better outcomes for patients, especially to reduce relapse. Reference Addington, Coldham, Jones, Ko and Addington54 The evidence from this review suggests we should also consider carer-focused interventions.

Implications for research

Over the past 40 or more years studies have repeatedly shown that relapse rates for people with psychosis can be substantially reduced through family interventions. The positive role that carers can play is clear: at the end of treatment relapse rates are nearly halved, an effect that diminishes over time but may still be clinically significant several years later. Reference Addington, Coldham, Jones, Ko and Addington54 This important role stands in stark contrast to carers’ often negative experience of services. Reference Tennakoon, Fannon, Doku, O'Ceallaigh, Soni and Santamaria55, 56 Our review suggests that carer-focused interventions are likely to be helpful to carers. What is less clear is which intervention is likely to benefit carers most, although psychoeducation and support groups are probably the best candidates. In addition, it is not possible to say from the evidence whether carer-focused interventions should be offered alongside traditional patient-focused family interventions for severe mental illness or offered separately. Combining patient-focused family interventions with interventions that focus on carers’ needs may offer advantages. Perhaps a next step could be to develop and evaluate, through a randomised controlled trial, a patient-focused and carer-focused family intervention, comparing it with a traditional patient-focused family intervention, using both patient and carer outcomes, to examine their possible interdependence in the context of first-episode psychosis. Future studies should be registered in advance, be reported in full to avoid reporting biases, be rigorously designed and clearly report information about the carer and patient participants, the interventions, comparison group and the primary outcomes of interest, and should take into consideration previous research regarding the most beneficial components of carer-focused interventions. Better methodology might well require better funding for this largely ignored group of carers.

In our view it is no longer sustainable, nor economically supportable, to ignore the central role that many carers have in the care and support, and effectiveness of therapy, of people with severe mental illness. With the newly emerging consensus on parity of esteem between mental and physical health, now is the time for concerted action to help those caring for people with some of the most impairing of mental health problems.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.