The lifetime prevalence of depression in low- and high-income countries is 11.1% and 14.6% respectively. Reference Bromet, Andrade, Hwang, Sampson, Alonso and de Girolamo1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is the third leading cause of burden of disease, as measured by Disability Adjusted Lived Years, and in 2030 could be the first. 2 Evidence suggests that exposures occurring during early years of life or even during pregnancy may have an important role in its development. Reference Brown and Harris3-Reference Schlotz and Phillips7 Based on the thrifty phenotype hypothesis, Reference Hales and Barker8 this programming effect could be a consequence of poor nutrition during fetal life, Reference Brown, Susser, Lin, Neugebauer and Gorman5,Reference Schlotz and Phillips7,Reference Stein, Pierik, Verrips, Susser and Lumey9,Reference Casper10 causing an overstimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which would increase fetal exposure to glucocorticoids and might produce lifelong effects on neurodevelopment, neurogenesis, hippocampal atrophy and lack of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Reference Kapoor, Dunn, Kostaki, Andrews and Matthews11,Reference Belmaker and Agam12 Most of the studies evaluating the programming effect of intrauterine growth on depression have used low birth weight as a proxy of intrauterine growth restriction. Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13-Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19 However, it is important to consider that birth weight is influenced by gestational age and intrauterine growth. According to the thrifty phenotype hypothesis, intrauterine growth retardation would programme the development of depression in adulthood, whereas gestational age would not be associated with depression through the mechanisms suggested by this hypothesis. It has also been suggested that the association between intrauterine growth retardation and depression in adulthood could be due to other mechanisms, such as maternal depression, intimate partner violence and socioeconomic position, which would be related to the occurrence of both low birth weight and depression in adulthood. Reference Kinsella and Monk20-Reference Campbell30 Therefore, these conditions should be considered as possible confounders and adjusted in the analysis.

With respect to the association between low birth weight and depression, the evidence is divided. Some studies have reported an association; Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas17,Reference Nomura, Brooks-Gunn, Davey, Ham and Fifer31-Reference Westrupp, Northam, Doyle, Callanan and Anderson34 others have not. Reference Gale and Martyn14,Reference Herva, Pouta, Hakko, Läksy, Joukamaa and Veijola16,Reference Nomura, Wickramaratne, Pilowsky, Newcorn, Bruder-Costello and Davey18,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa35,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36 Few have assessed the independent effect of gestational age Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13,Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas17,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Nomura, Brooks-Gunn, Davey, Ham and Fifer31,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36,Reference Dalziel, Lim, Lambert, McCarthy, Parag and Rodgers37 or intrauterine growth. Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa35,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36 A systematic review and meta-analysis by Wojcik et al reported a weak association (pooled odds ratio 1.15, 95% CI 1.00-1.32) between low birth weight and later depression. Reference Wojcik, Lee, Colman, Hardy and Hotopf38 This pooled effect may have been overestimated by publication bias. Furthermore, their review included ‘psychological distress’ as one of the outcomes, comprising a broad spectrum of events such as changes in emotional status, discomfort, demoralisation and pessimism about the future, anguish and stress, self-depreciation or a ‘maladaptive psychological functioning in the face of stressful life events’. Reference Ridner39,Reference Masse40 In spite of being a symptom of depression, psychological distress does not differentiate between depression and other non-affective disorders such as anxiety, and the inclusion of studies assessing psychological distress may have underestimated the association between birth weight and depression. Finally, as previously mentioned, low birth weight may be due to preterm birth, intrauterine growth retardation or a combination of both, and the review did not disentangle the effect of duration of gestation from that of intrauterine growth.

The aim of our systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the relationship between low birth weight, SGA and premature birth, and depression in adulthood.

Method

We carried out a systematic search in PsycINFO (1967-2013), Medline (1950-2013), LILACS (1986-2013), the Cochrane Library and SciELO (1999-2013) databases (final search 10 September 2013); no limit was applied for language or year of publication. The following terms were used in the search: (Depressive OR Depression OR ‘Depressive disorder’ OR ‘Mental Disorders’ OR ‘Mood Disorders’) AND (‘Birth Weight’ OR ‘Low-birth-weight’ OR ‘Very Low-birth-weight’ OR ‘Extremely Low-birth-weight’ OR ‘Fetal Weight’ OR ‘Fetal Growth Retardation’ OR ‘Premature Birth’ OR ‘Preterm Birth’ OR ‘Small for Gestational Age’). Included and excluded studies were collected following the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group41 We included original studies that assessed the risk of depression according to birth weight, gestational age or intrauterine growth among individuals over 18 years old, and in which depression was measured using self-rating scales or diagnostic interview. Studies that defined the outcome as psychological distress, common mental disorders and mood disorders, ‘depression and/or anxiety’ or any diagnosis that did not specifically identify the participant as having depression were not included. We also perused the reference lists of studies that were identified in the literature search.

Study selection and data collection

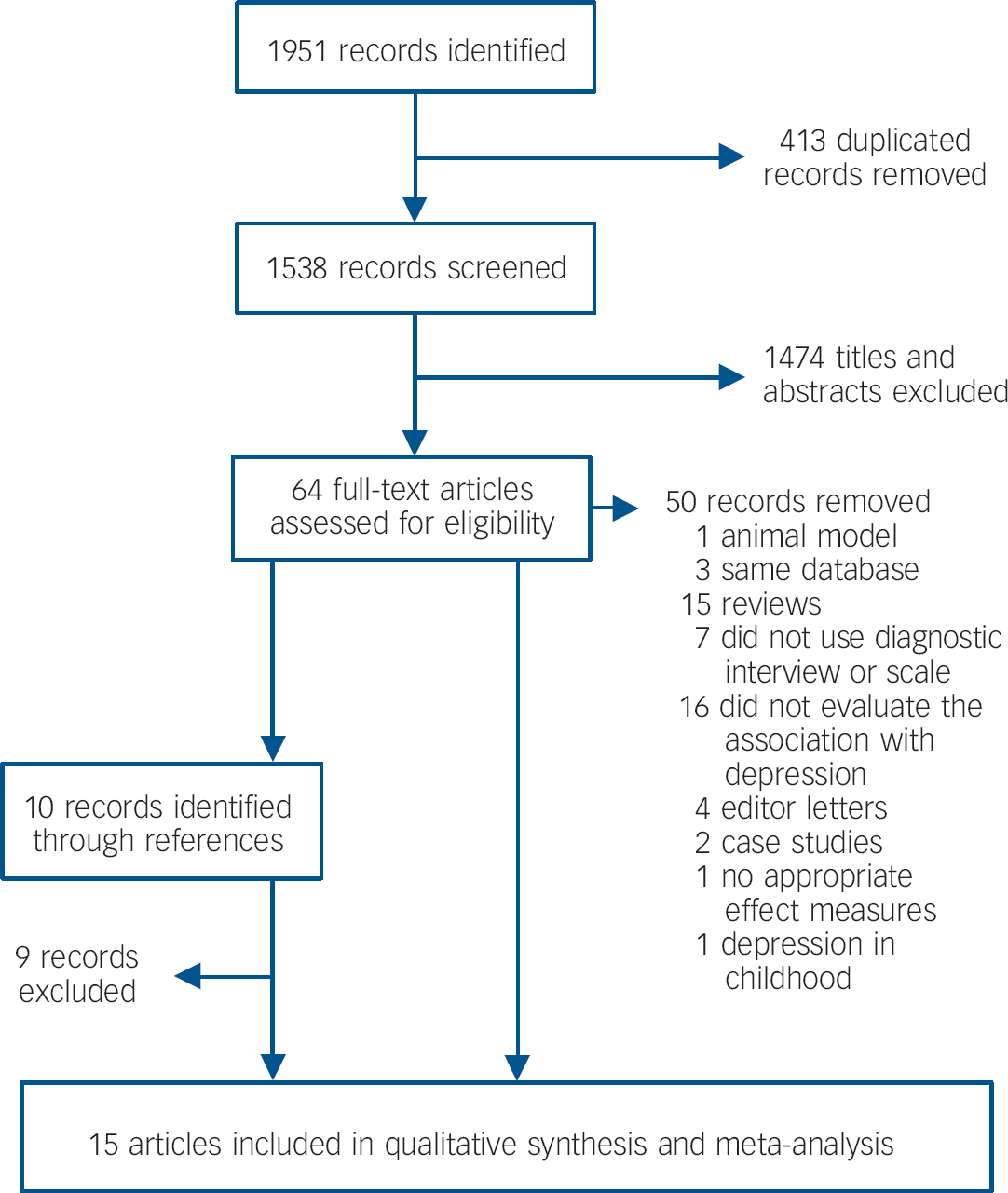

Eligibility assessment was performed independently by two reviewers (C.L. and G.V.F.). Initially, duplicate records were excluded, titles were screened and abstracts reviewed. Finally, full-text articles were examined (see Fig. 1). Two reviewers extracted the following data from the included articles: study design; methods used for measuring birth weight, premature birth, SGA and depression; age at assessment of depression; prevalence of the exposure and depression in the studied population; measure of association used; adjustment for confounders; if there was a clear description of exposure and outcome; sample size; categorisation of birth weight; studied population (hospital- or population-based); study direction (retrospective or prospective); and assessment of depression (interview or scale). Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or by a third expert (B.L.H.) when consensus was not achieved. We included only studies that reported the odds ratio (OR) for depression or that reported an estimate that could be transformed to OR, such as prevalence ratio or β from a logistic regression. If necessary we contacted the corresponding author for more information on the missing data that were needed for inclusion of the study. We contacted 13 authors for additional information; four responded, one of whom authored two studies, and provided additional estimates or handed us raw data to be analysed. Reference Gale and Martyn14,Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43

Statistical analysis

Separate meta-analyses were performed for each of the exposures of interest - low birth weight, premature birth and SGA - using random and fixed effects models to pool the estimates. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the I 2 statistic. As proposed by Higgins & Thompson, an I 2 value below 31% was considered mild, Reference Higgins and Thompson44 and a fixed effects model was used. Studies presenting results stratified by gender were included twice, as independent studies. In addition, Herva et al reported estimates for different low-birth-weight categories so they were included independently. Reference Herva, Pouta, Hakko, Läksy, Joukamaa and Veijola16 This did not alter the results, since each individual entered the analysis only once. Meta-regression was used to evaluate the contribution of several covariates to the heterogeneity among studies, Reference Berkey, Hoaglin, Mosteller and Colditz45 estimating the τ2 and adjusted R 2 in each model. Funnel plots and Egger’s test were used to evaluate the presence of publication bias. Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder46 The analyses were performed using Stata version 11.2 for Windows.

Results

Initially we identified 1951 studies. After removing 413 duplicates we screened 1538 titles and abstracts, following which 15 articles were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Of these, 14 evaluated the relationship between birth weight and depression in adulthood, Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13-Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas17,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33-Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 of which four provided estimates on the odds of depression among those with very low birth weight; Reference Herva, Pouta, Hakko, Läksy, Joukamaa and Veijola16,Reference Westrupp, Northam, Doyle, Callanan and Anderson34-Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36 nine evaluated the relationship between preterm birth and depression; Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13-Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas17,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36,Reference Dalziel, Lim, Lambert, McCarthy, Parag and Rodgers37,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 and four evaluated SGA and later depression. Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa35,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 Table 1 summarises the studies included in our meta-analysis; specific details can be found in online Table DS1. Additional details of methodological quality and assessment are given in online Table DS2.

Fig. 1 Publication search.

Ten studies were carried out in Europe, Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13-Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas17,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa35,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 two in the USA, Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36 and three in Australia or New Zealand. Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Westrupp, Northam, Doyle, Callanan and Anderson34,Reference Dalziel, Lim, Lambert, McCarthy, Parag and Rodgers37 In total, nine studies were population-based Reference Gale and Martyn14-Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas17,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42 and six were hospital-based; Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13,Reference Westrupp, Northam, Doyle, Callanan and Anderson34,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa35,Reference Dalziel, Lim, Lambert, McCarthy, Parag and Rodgers37,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 ten had a prospective design Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13,Reference Gale and Martyn14,Reference Herva, Pouta, Hakko, Läksy, Joukamaa and Veijola16,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Westrupp, Northam, Doyle, Callanan and Anderson34-Reference Dalziel, Lim, Lambert, McCarthy, Parag and Rodgers37 and five studies were retrospective. Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas17,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 All retrospective and five prospective studies Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13,Reference Gale and Martyn14,Reference Westrupp, Northam, Doyle, Callanan and Anderson34,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa35 used data from birth records; four measured birth weight, Reference Herva, Pouta, Hakko, Läksy, Joukamaa and Veijola16,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36 and one used maternal recall. Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42 With respect to the assessment of depression, four studies used a psychiatric interview, Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13,Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 three used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa35,Reference Dalziel, Lim, Lambert, McCarthy, Parag and Rodgers37 two used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D), Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33 and the remaining ten studies used other scales. Reference Almeida and Almeida47-Reference Zigmond and Snaith55 With respect to the age at assessment of depression, four studies evaluated depression among individuals older than 40 years. Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42

Birth weight

We identified 14 studies providing 21 estimates of the relationship between birth weight and depression in adulthood. Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13-Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas17,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33-Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 Thirteen estimates suggested higher odds of depression among those with low birth weight, but for six of these the confidence interval did not include the reference, Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas17,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33,Reference Westrupp, Northam, Doyle, Callanan and Anderson34,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42 whereas eight reported a negative association with a confidence interval including the reference. The fixed-effect pooled OR was 1.39 (95% CI 1.21-1.60), I 2 = 24.5% (Fig. 2(a)).

Table 1 Summary of studies included in meta-analyses

| First author (year) | Sample size | Exposure | Depression scale | Adjustment | Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alati (2007)Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan 4 | 3493 | BW | CES-D | Sociodemographic GA | Yes |

| Batstra (2006)Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra 13 | 258 | BW/GA | CIDI | Sociodemographic | No |

| Dalziel (2007)Reference Dalziel, Lim, Lambert, McCarthy, Parag and Rodgers 37 | 192 | GA | BDI-II | Not adjusted | No |

| Fan (2001)Reference Fan and Eaton 23 | 1824 | BW/GA/SGA | GHQ-28 | Sociodemographic | Yes GA |

| Gale (2004)Reference Gale and Martyn 14 | 8292 | BW/GA | Malaise Inventory | Sociodemographic GA/BW | No |

| Gale (2011)Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley 42 | 465/3211 | BW | HADS | Sociodemographic | Yes |

| Gudmundsson (2011)Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom 15 | 715 | BW/GA | Interview | Sociodemographic GA/BW | Yes |

| Herva (2008)Reference Herva, Pouta, Hakko, Läksy, Joukamaa and Veijola 16 | 8339 | BW | HSCL-25 | Sociodemographic GA | No |

| Mallen (2008)Reference Mallen, Mottram and Thomas 17 | 521 | BW/GA | HADS | Sociodemographic | Yes BW |

| Preti (2000)Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto 43 | 60 | BW/GA/SGA | Interview | Not adjusted | No |

| Raikkonen (2007)Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips 33 | 1371 | BW/GA | BDI/CES-D | Sociodemographic GA | Yes |

| Raikkonen (2008)Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa 35 | 234 | BW/SGA | BDI | Sociodemographic | No |

| Thompson (2001)Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker 19 | 810 | BW | GDS/GMS | Sociodemographic | No |

| Vasiliadis (2008)Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka 36 | 1101 | BW/GA/SGA | DIS | Sociodemographic | No |

| Westrupp (2011)Reference Westrupp, Northam, Doyle, Callanan and Anderson 34 | 149 | BW | SCL-90-R | Not adjusted | Yes |

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BW, birth weight; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies - Depression; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; GA, gestational age; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; GMS, Geriatric Mental State B version; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HSCL-25, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25; SCL-90, Symptoms Checklist; SGA, small for gestational age.

Table 2 shows that the pooled effect was lower among studies that provided separate estimates for men (OR = 1.12, 95% CI 0.82-1.54), whereas those providing estimates for women only had a pooled effect of 1.30 (95% CI 1.06-1.59) and those that included both genders reported the highest pooled effect (OR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.38-2.23), but these differences were not statistically significant. Pooled effects were heterogeneous, depending on the birth-weight categories being compared. Studies that compared the odds of depression in groups with low birth weight (⩽2.5 kg) v. normal birth weight (>2.5 kg) provided the highest pooled effect, and the lowest was observed among studies comparing birth weights of ⩽2.5 kg v. >3.5 kg and those evaluating very low birth weights (⩽2.0 kg). Studies that evaluated individuals younger than 40 years reported a smaller effect of low birth weight (OR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.05-1.47) than those evaluating individuals older than 40 years (OR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.37-2.22). Studies that did not control for possible confounders reported higher odds of depression among low-birth-weight individuals than those reporting adjusted estimates, but the effect of low birth weight was statistically significant even among studies that controlled for sociodemographic variables and gestational age (pooled OR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.15-1.60). Retrospective studies reported a higher odds ratio than those that used a prospective design. Sample size did not modify the estimated effect of birth weight on depression (Table 2). In univariate meta-regression models, birth-weight categorisation, study design, age at assessment of depression and exposure measure showed a τ2 of zero, i.e. each of these variables explained the total heterogeneity among studies (Table 2).

Table 3 shows that in the multivariate meta-regression, even after adjusting for exposure measure, age at assessment of depression, sample size and adjustment for confounders, the variables birth-weight category and study design maintained their association with heterogeneity among studies. Study design and birth-weight categorisation clearly lost their effects only when adjusted for each other, probably because five of the six studies with a retrospective design also compared low birth weight (⩽2.5 kg) with birth weights over 2.5 kg, so no further differentiation was possible between these two covariates. Funnel-plot and Egger’s tests (P = 0.683) showed no evidence of publication bias (Fig. 3). In addition, five studies included in the meta-analysis looked into the linear effect of birth weight, reporting estimates for continuous measures of birth weight, but none found a relation with adult depression (data not shown). Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13,Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42

Premature birth

We obtained eight estimates, from seven articles, on the relationship between premature birth and depression in adulthood. Only two estimates showed a positive association between premature birth and depression; the other six had confidence intervals including the reference. The random effects pooled estimate obtained was 1.08 (95% CI 0.77-1.52), I 2 = 47.8% (see Fig. 2(b)). The funnel plot was asymmetric, suggesting that small studies reporting higher odds of depression among those with preterm birth were missing (see Fig. 3). In the meta-regression we observed that sample size and sample population explained 66% and 100% of the heterogeneity among studies, respectively. Table 2 shows that small studies (n<500) and hospital-based studies, which were the same, reported a protective effect of preterm birth (OR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.32-1.06), whereas among studies with a sample size of 1000 individuals or more the pooled effect was 1.70 (95% CI 0.83-3.48). By pooling the studies with more than 500 individuals, we observed a pooled OR of 1.31 (95% CI 0.96-1.79). Furthermore, two studies reported continuous estimations of gestational age and depression during adulthood. Raikkonen et al found that for each increase of 1 day in gestational age there was a decrease in the odds of depression (OR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.95-0.99), Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33 whereas Gudmundsson et al found that shorter gestational time (weeks) increased the odds (OR = 1.11, 95% CI 1.01-1.22). Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15

Small for gestational age

Four studies, providing five estimates, evaluated the association between SGA and depression in adulthood. The pooled random effect OR was 1.14 (95% CI 0.64-2.03), I 2 = 49.7% (Fig. 2(c)). Because of the small number of studies included in this meta-analysis we did not perform a meta-regression or generate a funnel plot.

Fig. 2 (a) Fixed effects meta-analysis of studies evaluating low birth weight and depression during adulthood (CaPS, Caerphilly Prospective Study; HCS, Hertfordshire Cohort Study). (b) Random effects meta-analysis of studies evaluating premature birth and depression during adulthood. Weights are from random effects analysis. (c) Random effects meta-analysis of studies evaluating smallness for gestational age and depression during adulthood. Weights are from random effects analysis. A, estimate in men and women; M, estimate for men; F, estimate for women.

a. Birth weight 2000-2499 g.

b. Birth weight <1999 g.

Table 2 Univariate meta-regression and pooled odds ratio estimates of birth weight and premature birth on depression

| Birth weight | Premature birth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Footnote a | OR (95% CI) | P Footnote b | Adj. R 2, %Footnote c | N Footnote a | OR (95% CI) | P Footnote b | Adj. R 2, %Footnote c | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Both | 9 | 1.75 (1.38-2.23) | Index | –30.7 | 6 | 0.96 (0.56-1.66) | Index | –165.2 |

| Male | 6 | 1.12 (0.82-1.54) | 0.063 | 1 | 1.39 (0.78-2.49) | 0.604 | ||

| Female | 6 | 1.30 (1.06-1.59) | 0.068 | 1 | 1.01 (0.53-1.92) | 0.929 | ||

| Birth-weight category, kg | ||||||||

| ⩽2.5 v. ⩾2.5 | 7 | 2.15 (1.54-3.00) | Index | 100 | ||||

| ⩽2.5 v. ⩾3.5 | 7 | 1.19 (0.98-1.44) | 0.008 | |||||

| ⩽3 or ⩽3.5 v. ⩾3.5 | 2 | 1.59 (1.20-2.13) | 0.202 | |||||

| VLBW (⩽2)Footnote d | 3 | 1.01 (0.62-1.64) | 0.022 | |||||

| Adjustment | ||||||||

| Sociodemographic GA/BW | 9 | 1.35 (1.15-1.60) | Index | –37.3 | 1 | 1.32 (1.14-1.53) | Index | 46.0 |

| Sociodemographic | 10 | 1.41 (1.08-1.83) | 0.753 | 5 | 1.16 (0.69-1.94) | 0.787 | ||

| No adjustment | 2 | 4.94 (1.43-17.12) | 0.061 | 2 | 0.53 (0.26-1.09) | 0.162 | ||

| Age at assessment of depression | ||||||||

| <40 years | 15 | 1.24 (1.05-1.47) | Index | 100 | 8 | 1.08 (0.77-1.52) | ||

| ⩾40 years | 6 | 1.75 (1.37-2.22) | 0.045 | 0 | ||||

| Sample size, n | ||||||||

| <500 | 7 | 1.30 (0.87-1.94) | Index | –50.3 | 3 | 0.58 (0.32-1.06) | Index | 66.2 |

| 500-1000 | 4 | 1.55 (1.21-2.00) | 0.687 | 3 | 1.06 (0.63-1.76) | 0.207 | ||

| ⩾1000 | 10 | 1.33 (1.11-1.60) | 0.978 | 2 | 1.70 (0.83-3.48) | 0.061 | ||

| Sample population | ||||||||

| Hospital-based | 5 | 1.43 (1.04-1.96) | Index | –70.9 | 3 | 0.58 (0.32-1.06) | Index | 100 |

| Population-based | 16 | 1.38 (1.18-1.61) | 0.84 | 5 | 1.31 (0.96-1.79) | 0.047 | ||

| Study design | ||||||||

| Prospective | 15 | 1.19 (1.00-1.41) | Index | 100 | 2 | 0.51 (0.17-1.51) | Index | 34.3 |

| Retrospective | 6 | 1.89 (1.49-2.40) | 0.006 | 6 | 1.16 (0.82-1.65) | 0.267 | ||

| Exposure measure | ||||||||

| Research team | 9 | 1.03 (0.76-1.37) | Index | 100 | 1.46 (0.87-2.46) | Index | –45.9 | |

| Birth record or recall | 12 | 1.53 (1.30-1.79) | 0.034 | 0.77 (0.42-1.40) | 0.186 | |||

| Depression measure | ||||||||

| Interview | 5 | 1.47 (1.13-1.89) | Index | –168.1 | 4 | 1.09 (0.74-1.60) | Index | 66.2 |

| Scale depression | 13 | 1.41 (1.12-1.77) | 0.877 | 3 | 0.85 (0.23-3.17) | 0.207 | ||

| Scale depression/anxiety | 3 | 1.31 (1.04-1.66) | 0.856 | 1 | 1.32 (1.14-1.53) | 0.061 | ||

| Total | 21 | 1.39 (1.21-1.60) | 8 | 1.08 (0.77-1.52) | ||||

BW, birth weight; GA, gestational age; VLBW, very low birth weight.

a. Number of studies.

b. Value of P for meta-regression.

c. Adjusted R 2 represents proportion of between-study variance (heterogeneity) explained.

d. Very low birth weight compared with any other superior category.

Table 3 Multivariate meta-regression of birth-weight category and study design on other methodological covariates, in studies evaluating low birth weight

| AdjustmentFootnote a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure measure |

Age at

assessment of depression |

Sample size and

adjustment for confounders |

Mutually adjusted |

|

| Birth-weight category, kg | ||||

| ⩽2.5 v. ⩾2.5 | Index | Index | Index | Index |

| ⩽2.5 v. ⩾3.5 | 0.017 | 0.052 | 0.032 | 0.276 |

| ⩽3 or ⩽3.5 v. ⩾3.5 | 0.211 | 0.273 | 0.697 | 0.165 |

| VLBW (⩽2)Footnote b | 0.039 | 0.054 | 0.075 | 0.203 |

| Study design | ||||

| Prospective | Index | Index | Index | Index |

| Retrospective | 0.031 | 0.038 | 0.004 | 0.313 |

VLBW, very low birth weight.

a. Adjustment of birth weight category or study design by other methodological covariate(s) in multivariate meta-regression. Each model is independent from the other, and birth-weight category and study design were adjusted for each other only in the mutually adjusted model.

b. Very low birth weight v. any other higher category.

Discussion

We observed a positive association between low birth weight and depression in adulthood, whereas for preterm birth no association was observed. The small number of studies assessing the effect of SGA precluded any conclusion being drawn. For low birth weight, the funnel plot was symmetrical and the association was not modified by sample size, suggesting that the observed association was not due to publication bias. The stratified analysis showed that retrospective studies and those comparing individuals whose birth weights were ⩽2.5 kg v. >2.5 kg presented higher pooled effects, and these two covariates explained all the heterogeneity among studies.

Fig. 3 Funnel plots: (a) estimates from studies evaluating low birth weight; (b) estimates from studies evaluating premature birth. lnOR, natural logarithm of the odds ratio, s.e., standard error.

Converse to the notion that the comparison among the most extreme categories would increase the magnitude of the association, in our meta-analysis the highest pooled effect was observed for studies comparing low birth weight (⩽2.5 kg) with normal birth weight (>2.5 kg). Adjustment for age at assessment of depression did not change the differences in pooled effects of birth categorisation. However, the association was lost after adjusting for study design; the pooled odds ratios among studies that compared birth weights of ⩽2.5 kg v. >3.5 kg changed from 0.55 (95% CI 0.36-0.84) to 0.71 (95% CI 0.38-1.39). This suggests that retrospective design could be responsible for the differences in the pooled estimates of birth categorisation. Another explanation could be the fact that higher birth weight might also increase the chances of later mental disease, Reference Herva, Pouta, Hakko, Läksy, Joukamaa and Veijola16,Reference Colman, Ploubidis, Wadsworth, Jones and Croudace56-Reference Van Lieshout and Boyle58 which would explain why continuous birth weight does not show a linear association with adult depression, but studies showing this ‘U’ or ‘J’ association specifically for depression are scarce. Furthermore, in spite of not explaining the heterogeneity among studies, the stratified analysis showed that studies that controlled for confounding by socioeconomic and demographic variables reported a smaller odds ratio than studies that reported crude estimates. Because low birth weight and depression are related to socioeconomic position and this relationship depends on the tool used to assess it, Reference Eaton, Muntaner, Bovasso and Smith22,Reference Melchior, Chastang, Head, Goldberg, Zins and Nabi59,Reference Parker, Schoendorf and Kiely60 confounding by socioeconomic position should overestimate the measure of association, as we observed. Therefore future studies should appropriately address this issue on confounding.

Contrary to the findings of Wojcik et al in a previous meta-analysis, Reference Wojcik, Lee, Colman, Hardy and Hotopf38 we observed that low birth weight increased the odds of depression in adulthood. Our controversial findings could be because we did not include studies that evaluated psychological distress Reference Colman, Ploubidis, Wadsworth, Jones and Croudace56,Reference Berle, Mykletun, Daltveit, Rasmussen and Dahl61-Reference Wiles, Peters, Leon and Lewis67 and included only studies among adults. On the other hand, a meta-analysis by Burnett et al found that children born preterm and with low birth weight had increased odds of later anxiety/depression, Reference Burnett, Anderson, Cheong, Doyle, Davey and Wood68 but once again in this review depression was not individually assessed, and also Burnett et al evaluated individuals in the age range 10-25 years.

Strengths and limitations

We did not search for studies in other databases such as EMBASE, but we do not believe this would have altered our results. Wojcik et al searched EMBASE and identified the same studies (up to 2011) that were identified in our search. Reference Wojcik, Lee, Colman, Hardy and Hotopf38 Furthermore, it is unlikely that the exclusion of three studies that did not provide information on the measure of association to be included in the meta-analysis biased the pooled estimate away from the null. Reference Bellingham-Young and Adamson-Macedo69-Reference Boyle, Miskovic, Van Lieshout, Duncan, Schmidt and Hoult71 Sample sizes in these studies were small (n<500) and they reported an association between birth weight and depression in the same direction we have reported. Intimate partner violence, maternal depression during pregnancy and mother’s education and wealth could also be associated with poor perinatal outcomes and depression in adulthood, involving different pathways to the one proposed. Reference Grigoriadis, VonderPorten, Mamisashvili, Tomlinson, Dennis and Koren21-Reference Campbell30 In our meta-analysis, most of the studies reported estimates that were adjusted for some of these possible confounders, such as sociodemographic variables and maternal depression. On the other hand, none of the included studies controlled for intimate partner violence. Therefore, we cannot rule out that the observed association was due to residual confounding by intimate partner violence.

With respect to the assessment of the outcome, only four of the 15 included studies used diagnostic interviews for the assessment of depression, Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13,Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 which is considered the gold standard for depression diagnosis. Nine used screening scales, the BDI and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale subscale for depression, Reference Beck, Steer and Carbin48,Reference Zigmond and Snaith55 that are able to differentiate between depression and anxiety, Reference Batstra, Neeleman, Elsinga and Hadders-Algra13,Reference Herva, Pouta, Hakko, Läksy, Joukamaa and Veijola16,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33-Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa35,Reference Dalziel, Lim, Lambert, McCarthy, Parag and Rodgers37,Reference Gale, Sayer, Cooper, Dennison, Starr and Whalley42 or used a subscale for depression or a semistructured interview to confirm depression. Reference Herva, Pouta, Hakko, Läksy, Joukamaa and Veijola16,Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Osmond and Barker19,Reference Fan and Eaton23,Reference Westrupp, Northam, Doyle, Callanan and Anderson34 The remaining two studies used screening scales (the CES-D and Malaise Inventory) that are unable to distinguish between depression and anxiety. Reference Alati, Lawlor, Mamun, Williams, Najman and O'Callaghan4,Reference Gale and Martyn14 The use of screening scales to assess the occurrence of depression may have introduced a classification error. Nevertheless, it is important to stress that such bias is non-differential, so would tend to underestimate any association. On the other hand the assessment of the outcome was not a source of heterogeneity, as shown in Table 2. Therefore, we believe that the pooled estimates were not biased by the use of screening scales to assess depression.

Our meta-analysis had the strength of including studies of not only low birth weight but also premature birth and SGA, trying to disentangle the complex association between birth conditions and later disease. Furthermore, using meta-regression, we identified possible sources of heterogeneity; study design and birth-weight categorisation explained the heterogeneity among studies that evaluated the relationship between birth weight and depression.

Associations with depression

Birth weight is mainly determined by the infant’s gestational age and intrauterine growth, therefore the biological association between low birth weight and later depression observed in this meta-analysis should be explained by one of these two factors. Premature birth showed an estimate close to the reference. Nevertheless, publication bias may have underestimated this association, as the pooled estimate among small studies was in the opposite direction to that observed among studies with a sample size greater than 1000, and when we estimated the pooled estimate among studies that evaluated more than 500 individuals we observed a pooled OR of 1.31 (95% CI 0.96-1.79), which just includes the reference. In addition, two studies found an inverse relationship between continuous gestational age and the odds of later depression. Reference Gudmundsson, Andersson, Gustafson, Waern, Ostling and Hallstrom15,Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Kajantie, Heinonen, Forsen and Phillips33 Consequently, we cannot rule out that premature birth might be associated with adult depression, and more studies evaluating this relationship are necessary. Nonetheless, we should point out that the isolated effect of gestational age is not related to the thrifty phenotype hypothesis and could be part of other mechanisms, such as the ones proposed earlier. Few studies evaluated SGA and their results were clearly heterogeneous, with some studies reporting ORs higher than 2.0, Reference Raikkonen, Pesonen, Heinonen, Kajantie, Hovi and Jarvenpaa35,Reference Preti, Cardascia, Zen, Pellizzari, Marchetti and Favaretto43 whereas Vasiliadis et al observed a protective association with SGA; Reference Vasiliadis, Gilman and Buka36 however, for all included studies the confidence interval included the unity. Therefore, we were unable to draw a conclusion on the association between depression and SGA.

Future research

On the basis of these findings, we believe that special attention should be focused on children of low birth weight, as they may be a high-risk group for future development of depression. In addition, more research is needed on the effect of premature birth and intrauterine growth on depression in adulthood. New studies should use a prospective design, and diagnosis of depression should be based on diagnostic interview or screening scales that are clearly able to differentiate depression from anxiety. Furthermore, these studies should also control the estimates for sociodemographic, biological and other variables such as intimate partner violence and maternal depression.

Funding

The research was supported by FundaçÃo de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Programa Pesquisador Gaúcho, Processo 11/1815-8.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the authors of the included papers who kindly gave us access to their databases or provided new estimates or additional information concerning their research.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.