With an estimated prevalence of 2.6–4.5%, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common mental disorders among children and adolescents.Reference Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye and Rohde1 Characterised by hyperactivity, impulsivity and attention deficit, ADHD affects not only those under age 18; symptoms of ADHD often persist into adult life.Reference Kessler, Adler, Barkley, Biederman, Conners and Demler2,Reference Huang, Chu, Cheng and Weng3 Increased risk of mood disorder, conduct disorder and substance use disorder have been found in children with ADHD,Reference Yoshimasu, Barbaresi, Colligan, Voigt, Killian and Weaver4 as well as increased risk of suicide,Reference Balazs and Kereszteny5 accidents,Reference Altun, Guven, Akgun and Acikel6–Reference Tai, Gau and Gau8 traffic violations and road injuries.Reference Vaa9,Reference Curry, Metzger, Pfeiffer, Elliott, Winston and Power10 Higher premature mortality has consequently been found, with accidents, trauma or suicide as main causes of death.Reference Barbaresi, Colligan, Weaver, Voigt, Killian and Mortality11–Reference Chen, Chan, Wu, Lee, Lu and Liang14 Core ADHD symptoms of inattention, distractibility and impulsivity,Reference Cairney15,Reference Jerome, Habinski and Segal16 as well as comorbidity with depression, oppositional defiant disorder and/or conduct disorder may partly account for these risks.Reference Vaa9

Debate regarding risk of mortality and medication for ADHD

The debate concerning beneficial and adverse effects of stimulant treatment for ADHD is still ongoing. Treatment guidelines for ADHD suggest stimulants as a first-line intervention, and these have been reported as effective in reducing ADHD symptoms in more than 70% of childhood cases,Reference Vaughan and Kratochvil17,18 as well as more specific reports of reduced trauma-related emergency service utilisationReference Man, Chan, Coghill, Douglas, Ip and Leung19–Reference Ruiz-Goikoetxea, Cortese, Aznarez-Sanado, Magallon, Alvarez Zallo and Luis22 and suicidal behaviours.Reference Ljung, Chen, Lichtenstein and Larsson23,Reference Liang, Yang, Kuo, Liao, Lin and Lee24 One recent meta-analysis of double-blind randomised controlled trials supported stimulants as preferred first-choice medications for the short-term treatment of ADHD,Reference Cortese, Adamo, Del Giovane, Mohr-Jensen, Hayes and Carucci25 and a recent meta-analysis concluded that people with ADHD treated with stimulants had lower risk of unintentional injuries (OR = 0.838–0.922) than those not receiving treatment.Reference Ruiz-Goikoetxea, Cortese, Aznarez-Sanado, Magallon, Alvarez Zallo and Luis22 In addition, a population-based study found that longer duration of stimulant use (more than 90 days) was associated with reduced suicide risk.Reference Liang, Yang, Kuo, Liao, Lin and Lee24 However, stimulants are recognised to have adverse effects of anorexia, sleep problems, stomach-ache and headache,Reference Storebo, Pedersen, Ramstad, Kielsholm, Nielsen and Krogh26 and a large longitudinal nationwide cohort study reported an increased risk of cardiovascular events in children with ADHD receiving stimulants relative to general population and unmedicated children with ADHD as comparators (adjusted hazard ratios AHR = 1.83–2.20).Reference Dalsgaard, Kvist, Leckman, Nielsen and Simonsen27 On the other hand, a meta-analysis concluded that stimulant use was not associated with increased risks of sudden death or stroke.Reference Mazza, D'Ascenzo, Davico, Biondi-Zoccai, Frati and Romagnoli28 A recent qualitative systematic review of studies based on within-individual analyses, which control for time-independent confounders, suggested short-term beneficial effects of ADHD medication on injuries, motor vehicle accidents, education and substance use disorder.Reference Chang, Ghirardi, Quinn, Asherson, D'Onofrio and Larsson29

With rising stimulant prescriptions (e.g. a more than 1.5-fold increase in the past decadeReference Olfson, Druss and Marcus30) and the long-term pharmacotherapy implicated (nearly 50% of patients were found to continue medication use for at least 2–3 years after initiating drug treatmentReference Hechtman31), it is important to investigate associations of stimulants with adverse outcomes, including mortality, given the evidence (albeit conflicting) cited above. Previous investigations have resulted in inconsistent findings on excess mortality in children with ADHD compared with healthy childrenReference Barbaresi, Colligan, Weaver, Voigt, Killian and Mortality11–Reference London and Landes13 and investigations of associations with stimulant therapy are even more scant. McCarthy et al reported that receipt of stimulants or atomoxetine was not associated with a raised standardised mortality ratio (SMR) for sudden death; however, they did find increased associated suicide mortality in patients aged 11–14 years (SMR = 161.9, 95% CI 19.6–584.9).Reference McCarthy, Cranswick, Potts, Taylor and Wong32 Another longitudinal study using within-patient comparisons found a 19% reduction in suicide-related events, including suicide mortality, during periods of stimulant treatment.Reference Chen, Sjolander, Runeson, D'Onofrio, Lichtenstein and Larsson33 It is therefore still unclear whether stimulant use is associated with an increased or decreased mortality in children and adolescents with ADHD; furthermore, there has been no study to date investigating associations with all-cause, natural-cause and unnatural-cause mortality simultaneously. In the present study, we assembled a nationwide population-based cohort study to investigate associations of MPH use, the only licensed stimulant for ADHD in Taiwan, with all-cause, natural-cause and unnatural-cause mortality in children with ADHD. We also investigated patterns of MPH prescription in relation to mortality.

Method

Data source

The National Health Insurance (NHI) programme in Taiwan is a single-payer insurance system operated by the government. This system was established in 1995 to support health nationwide and prevent social problems caused by poverty and disease. By December 2010, over 23 million people were enrolled nationwide, with a coverage of 99.6%. The Bureau of National Health Insurance gathered information on medical service utilisation, prescribed drugs and procedures from out-patient, emergency room visits or hospital admissions, and assembled the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) for research use.Reference Kaur, Muthuraman and Kaur34 The NHIRD includes claims data from 183 480 insured children aged 4–17 years newly diagnosed with ADHD (ICD-9: 314.xx) during the period 2000–2010. The reason for choosing this age group for data extraction was that ADHD was rarely diagnosed outside this range. The focus of the analysis was on methylphenidate (MPH) treatment. In Taiwan, MPH is the only stimulant approved for treatment of ADHD. Atomoxetine, a non-stimulant, received regulatory approval and was made available in Taiwan in 2007; however, atomoxetine has a much lower rate of prescription compared with MPH (4% of all ADHD patients).Reference Lee, Yang, Shyu, Yuan, Yang and Lee35 From this cohort we found 68 096 children who had received MPH treatment between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2010. This exposed group were compared with 68 096 children with ADHD who had not received MPH treatment during that period and who were matched for gender, age at ADHD first diagnosis (within 1 year) and year of ADHD first diagnosis. The date of first MPH prescription for those children receiving it was defined as the index date for both MHP-receiving and comparison participants. Both the exposure and comparison cohorts were followed up from the index date until death, migration or the end-point of 31 December 2013 (Fig. 1). Linked information from the Mortality Register from 2000 to 2013 was provided by the Department of Health, the Executive Yuan (executive branch of the government) of Taiwan.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of data collection in this study.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Taiwan Normal University (reference: 201703HM006). Written consent from the study participants was not required because the contents of the NHIRD and the Mortality Register are de-identified and anonymised for research purposes. The IRB gave a formal written waiver of the need for informed consent.

Outcome variables and covariates

Our MPH-receiving and comparison participants were evaluated for all-cause mortality within the follow-up period. Unnatural-cause mortality was defined on the basis of ICD-9 External Causes of Death codes for suicide (ICD-9 codes: E950–E959, E980–E989), accidents (E800–E949) and homicide (E960–E969). Natural-cause mortality was defined as all other causes. The coding system for mortality in Taiwan during the study period registered only a primary cause of death code to be entered for each death.

Our covariates included age (at ADHD diagnosis), gender, urban versus rural residence, recorded insurance premium, frequency of recent out-patient visits and the presence or not of each of the following diagnoses before the ADHD diagnosis: congenital anomaly or birth defects (ICD-9: 740–759), intellectual disability (317–319), depressive disorder (296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311), autism (299), substance use disorder (303–304), conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (312, 313.81). National health insurance premiums are levied in Taiwan according to the individual's monthly income (here, the main caregiver paid the premiums), and consequently served as an indicator of the family's economic status for this analysis, classified into three categories: monthly income ≤NT$20 000, NT$20 000–39 999 and ≥NT$40 000 (US$1 = NT$32.1 in 2010). The number of outpatient visits (medical claims past 1 year of first diagnosis date of ADHD) served as an indicator of medical service utilisation, and was classified into three categories: 0–10, 11–20 and ≥21. Finally, we extracted data on time from first ADHD diagnosis to first MPH prescription, and defined a covariate representing MPH dose per 100 days. Incident ADHD cases from 2000–2010 were children without ADHD diagnosis from 1998 to the first ADHD medical claim in our database. Children who received MPH before this first ADHD diagnosis date were excluded. Information on prescription of MPH was fully covered by the health insurance data-set throughout the study period owing to the requirement to register controlled medication in Taiwan.

Statistical analysis

The study design that we used has fixed time points where each person has observations at which MPH is measured. Such a study design is common for longitudinal studies. In particular, a time-varying covariate (MPH) is measured in each individual at each time interval and all intervals are of the same length (in our study, 1 year). In this context, the regression coefficients represent the association between MPH and an event (death) that occurs during the subsequent interval. Using this method each observation interval is considered a mini-follow-up study in which the current risk factors are updated to predict events in the interval. Once an individual has an event in a particular interval, all subsequent intervals for that individual are excluded from the analysis.Reference Ngwa, Cabral, Cheng, Pencina, Gagnon and LaValley36 MPH prescription was measured each year during the study period. Annual average days of MPH prescriptions served as the main exposure variable. The event was considered as censored if no death occurs in that follow-up year. The risk of mortality during the follow-up period was calculated through repeated- measures time-dependent Cox regression. Repeated-measures time-dependent Cox regression models adjusted for competing risk were used to estimate associations of MPH with mortality outcomes, considering other causes of mortality aside from the target cause as competing risk events for each participant. Although the participants were matched by gender and age at ADHD diagnosis, the analysis unit was the follow-up period (1 year) not the participant. Therefore, we also adjusted for gender and age in the regression analysis. Cumulative incidences were calculated and results of log-rank tests were obtained using the Fine and Gray method.Reference Gray37,Reference Fine and Gray38 The model was analysed first with all samples. Subsequently, stratified analyses by gender and age groups (age 4–11 years and 12–17 years) were performed.

Several multivariate adjusted models were calculated. Model 1 incorporated gender, age, levels of urbanisation and income, and out-patient visits (medical claims past 1 year of first diagnosis date of ADHD). Model 2 incorporated further adjustments for congenital anomaly or birth defect, intellectual disability, depressive disorder, autism, substance use disorder, and conduct disorder or ODD, diagnosed before the index date. A further subanalysis was performed to investigate the effect of duration between the first ADHD diagnosis and the first MPH prescription on mortality in the MPH-treated subgroup. Data management was performed using SAS version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Cumulative incidences and the Cox model in the competing-risk analysis were calculated using the R package.39

Results

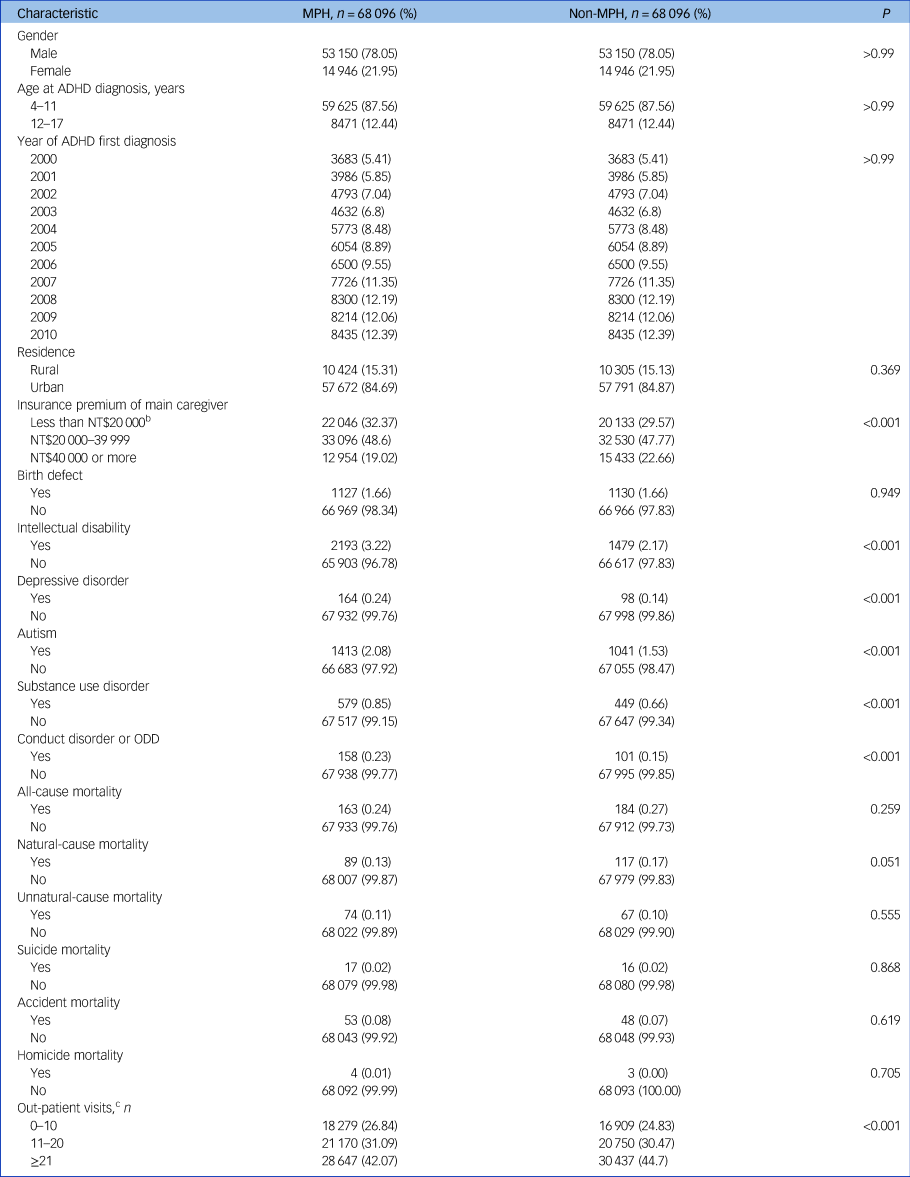

As described, a total of 68 096 MPH-treated children and 68 096 matched comparison children with no MPH treatment were included in our analysis. As summarised in Table 1, gender, age at first diagnosis and the year in which ADHD was first diagnosed were matched effectively between groups. Levels of urbanisation were also similar between the two groups. Higher proportions of comorbid intellectual disability, depressive disorder, autism, substance use disorder and conduct disorder/ODD were noted in MPH-treated children than in those without MPH treatment.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristicsa of the methylphenidate-receiving and comparison cohorts of children/adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

MPH, methylphenidate; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder.

a. Pre-existing diagnoses: congenital anomaly or birth defect (ICD-9: 740–759); intellectual disability (ICD-9: 317–319); depressive disorder (ICD-9: 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311); autism (ICD-9: 299); substance use disorder (ICD-9: 303–304); conduct disorder or ODD (ICD-9: 312, 313.81).

b. 1 US$ = 32.1 New Taiwan dollars (NT$) in 2010.

c. Medical claims past 1 year of first diagnosis date of ADHD.

Results of univariate repeated-measures time-dependent analyses showed that MPH treatment was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality (HR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.34–0.69), natural-cause mortality (HR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.89), unnatural-cause mortality (HR = 0.35, 95% CI 0.18–0.66) and mortality due to accidents (HR: 0.45, 95% CI 0.23–0.89) than in non-MPH-treated counterparts (Table 2; and supplementary Fig. 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.129). There was only 1 death by suicide in the MPH-treated follow-up year (incidence 0.06 per 10 000 person-years) compared with 32 in the comparison follow-up year (incidence 0.42 per 10 000 person-years). No homicide deaths occurred in the MPH-treated follow-up year, compared with 7 in the comparison follow-up year (incidence 0.09 per 10 000 person-years). Stratified analysis by gender or age showed that reductions in mortality associated with MPH use were only statistically significant in males and those diagnosed at a younger age (aged 4–11 years), although coefficients did not differ substantially between age groups.

Table 2 Univariate analysis of the association between methylphenidate and mortality outcomes in children/adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

MPH, methylphenidate; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; HR, hazard ratio; n.a., no available owing to zero deaths among the MPH cohort.

a. Causes of death: suicide, ICD-9: E950–E959, E980–E989; accident, ICD-9: E800–E949; homicide, ICD-9: E960–E969; unnatural-cause (suicide, accident and homicide), natural-cause (all-cause mortality excluded suicide, Accident and homicide).

b. Time-dependent repeated measures analysis, MPH measured each year during the study follow-up.

c. All-cause mortality analysed by log-rank test, specific-cause mortality analysed by modifying log-rank test using the Fine and Gray method.

d. Per 10 000 person-years.

After adjusting for listed potential confounders, although the effect attenuated, MPH use was still associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality (AHR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.67–0.98) (Table 3). This association also remained statistically significant in the subgroups who were male or aged 4–11 years.

Table 3 Multivariate analysis of the association between methylphenidate and mortality outcomes in children/adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; n.a., Non-available due to zero deaths among MPH cohort.

a. Model 1: adjusted for gender, age, residence, insurance premium and out-patient visits (medical claims past 1 year of first diagnosis date of ADHD).

b. Model 2: Model 1, further adjusted for pre-existing diagnoses and causes of death. Pre-existing diagnoses: congenital anomaly or birth defect (ICD-9: 740–759); intellectual disability (ICD-9: 317–319); depressive disorder (ICD-9: 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311); autism (ICD-9: 299); substance use disorder (ICD-9: 303–304); conduct disorder or ODD (ICD-9: 312, 313.81). Causes of death: suicide, ICD-9: E950–E959, E980–E989; accident, ICD-9: E800–E949; homicide, ICD-9: E960–E969; unnatural-cause (suicide, accident and homicide), natural-cause (all-cause mortality excluded suicide, Accident and homicide).

c. Unit: per 100 days of MPH use.

d. Adjusted for other-cause mortality by competing-risk-adjusted Cox regression.

Analyses presented in Table 4 describe factors associated with all-cause mortality in the MPH-receiving cohort, specifically investigating timing and duration of MPH prescription as predictors. The mean interval from ADHD first diagnosis to MPH first prescription was 307.4 days (s.d. = 594.9 days). Higher all-cause mortality was found in those with a longer time between diagnosis of ADHD and MPH commencement (AHR = 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.09), and lower all-cause mortality was found in those with a longer duration of treatment (AHR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.70–0.98).

Table 4 Multivariate analysisa of factors predicting all-cause mortality in children and adolescents receiving methylphenidate prescription (n = 68 096)

MPH, methylphenidate; HR, hazard ratio; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder.

a. Factors entered simultaneously as covariates.

b. Period between attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder first diagnosis date and the MPH first prescription date, unit: per 100 days.

c. 1 US $ = 32.1 New Taiwan dollars (NT$) in 2010.

d. Medical claims past 1 year of first diagnosis date of ADHD.

e. Pre-existing diagnoses: congenital anomaly or birth defect (ICD-9: 740–759); intellectual disability (ICD-9: 317–319); depressive disorder (ICD-9:296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311); autism (ICD-9: 299); substance use disorder (ICD-9: 303–304); conduct disorder or ODD (ICD-9: 312, 313.81).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate associations of MPH use in ADHD with all-cause, natural and unnatural mortality. Our primary finding was that MPH use was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality. Within the group receiving MPH, a longer interval between diagnosis and first treatment was associated with an increased risk of mortality, whereas longer treatment duration was associated with lowered risk.

MPH and decreased risk of mortality

Our findings showed that the adjusted hazard ratio for all-cause mortality was significantly lower in the MPH-receiving group than in the comparison group, and that no significant differences were found in natural-cause mortality in adjusted analyses. Recently, a concern was reported that cardiovascular events are increased two-fold in MPH users,Reference Dalsgaard, Kvist, Leckman, Nielsen and Simonsen27 although other self-controlled and population-based cohort studies have not found associations with risk of cardiac events.Reference Berger40–Reference Winterstein, Gerhard, Kubilis, Saidi, Linden and Crystal42 Previous studies have also reported no increase in the standardised mortality ratio for sudden death in patients receiving MPH.Reference Mazza, D'Ascenzo, Davico, Biondi-Zoccai, Frati and Romagnoli28,Reference McCarthy, Cranswick, Potts, Taylor and Wong32 Our findings thus add to the evidence that MPH use is not associated with an increased risk of natural-cause mortality.

Unnatural-cause and suicide mortality

Our findings that MPH use was associated with decreased hazard ratios for both natural and unnatural causes of mortality in univariate analyses are in agreement with previous studies.Reference Jerome, Habinski and Segal16,Reference Chang, Quinn, Hur, Gibbons, Sjolander and Larsson21,Reference Liang, Yang, Kuo, Liao, Lin and Lee24,Reference Man, Ip, Chan, Law, Leung and Ma43,Reference Chen, Yang, Liao, Kuo, Liang and Huang44 However, after adjusting for demographic variables and comorbidities, these protective effects remained statistically significant only for all-cause mortality as an outcome. It should be borne in mind that mortality events were very rare and statistical power was thus limited for detecting these specific cause-of-death subgroups. Of note, in the fully adjusted models, the significant hazard ratio of 0.81 for all-cause mortality associated with MPH use was more strongly accounted for by the hazard ratio of 0.72 for its unnatural-cause component (141 deaths) than by the 0.85 for natural-cause mortality. Furthermore, accident-related deaths (n = 101) were the principal component of unnatural mortality, so are likely to be responsible for a high component of the all-cause reduction, despite not being statistically significant as a specific cause of death.

Age and gender differences

Our findings indicated that the association of MPH with reduced mortality was more prominent in the younger age group. The results extended previous findings that people diagnosed with ADHD in childhood and adolescence have a lower risk of mortality than those diagnosed in adulthood.Reference Dalsgaard, Ostergaard, Leckman, Mortensen and Pedersen12 It is unclear why the association of MPH with reduced all-cause mortality varies with age at first ADHD diagnosis; however, it has been reported that initiating MPH at an earlier age (aged 6–7) is associated with a lower lifetime risk of non-alcohol substance use disorder than later initiation (aged 8–12).Reference Mannuzza, Klein, Truong, Moulton, Roizen and Howell45 Since substance misuse can result in higher risk of mortality in the general population,Reference Lee, Chen, Tan, Chou, Wu and Chan46 earlier identification and initiation of MPH treatment in children with ADHD may also be able to decrease the excessive mortality. In addition, greater comorbidity in the MPH-treatment group implies that higher severity/complexity of difficulties is associated with greater prescription and/or uptake of prescriptions. Greater comorbidity encompassing depression, conduct disorder and substance misuse elements suggests that a higher level of mortality from unnatural causes (accidents, assaults, suicide, etc.) might be expected in the MPH-receiving group, which makes the observed reduction detected all the more striking. Receipt of a diagnosis at a younger age might also relate to greater severity of difficulties and could be a subject for further research in clinical samples.

Although MPH treatment was also associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality in male but not female participants, the effect sizes were similar and the differences may reflect differences in sample size and event numbers. The lack of a statistically significant effect for females compared with males may be due to the smaller stratum size and insufficient statistical power since ADHD diagnoses, referral for treatment, medication for ADHD, and mortality are all lower among females.Reference Russell, Ford and Russell47,Reference Rucklidge48

Earlier and continuous treatment

This is the first study reporting that a longer interval between first ADHD diagnosis and first prescription of MPH is associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality. In addition, we also found that participants receiving longer-duration MPH treatment had lower risk of all-cause mortality. It has been reported that people diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood have a higher risk of mortality than those diagnosed in childhood and adolescence.Reference Dalsgaard, Ostergaard, Leckman, Mortensen and Pedersen12 Combined with our results, an implication is that receiving a diagnosis earlier and receiving medication earlier may reduce the risk of later adverse consequences. As described, one possible reason for this may be benefits of MPH treatment in reducing rates of accident-related causes of death.Reference Man, Chan, Coghill, Douglas, Ip and Leung19,Reference Chang, Quinn, Hur, Gibbons, Sjolander and Larsson21,Reference Lichtenstein and Larsson49 Of relevance, Mannuzza et al described a higher risk of developing substance use disorder associated with MPH initiation at a later ageReference Mannuzza, Klein, Truong, Moulton, Roizen and Howell45 and substance misuse may link to worse outcomes. For longer-duration MPH treatment, survival bias needs to be considered: i.e. early mortality reducing the length of time over which treatment is recorded. However, since the analysis was based on a repeated-measures time-dependent Cox regression model, the number of deaths was too few to generate this reverse effect.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study included the population-based cohort design, which minimised the likelihood of selection and recall bias. The linkage to the National Mortality Register allowed us to investigate the association of MPH use and mortality, and we were able to adjust for a wide range of demographic factors and comorbidities. The competing-risk model we applied also enhanced our precision for target causes of death.

Notwithstanding, there are several limitations that should be borne in mind when drawing inferences from our findings. First, diagnoses obtained from the NHIRD were based on physicians’ clinical judgements rather than structured research-quality interviews. Second, this is an observational study using data from the population in Taiwan, and generalisability to other populations needs to be established. Third, although we adjusted for multiple covariates, information lacking in the database precluded the measurement of other possible confounders, such as family history, psychosocial stressors, effect of behavioural therapy or severity of comorbidities. Therefore, as with all observational data, it is not possible to be conclusive about whether the association with lower mortality is related to an effect of MPH treatment itself or whether other characteristics of the children receiving MPH may account for the lower risk (i.e. confounding by indication). Finally, although the cohort sizes were large, the number of deaths was small and this limited statistical power, particularly for investigation of cause-specific mortality and of subgroup differences. Because of the relatively low number of deaths and limited follow-up duration, longer-term studies with larger samples are warranted to delineate further associations with specific causes of death and intervening causal pathways. To generalise the findings, similar population-based cohort studies from other countries are warranted.

Implications

Our finding that MPH use was associated with a reduced overall mortality among people with ADHD, especially those treated earlier after diagnosis and with longer treatment duration, adds to a growing observational literature drawing on administrative data and should reassure families that methylphenidate does not at least appear to be related to increased mortality.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.129.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Central Bureau of National Health Insurance, the Department of Health, and managed by the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available.

Acknowledgements

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, and managed by the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes, Republic of China.

Author contributions

V.C.-H.C., H.-L.C., S.-I.W. and C.T.-C.L. formulated the research questions; V.C.-H.C. and C.T.-C.L. developed the concept and design of the study; C.T.-C.L. analysed the data. V.C.-H.C., H.-L.C., S.-I.W., M.-L.L., M.D., R.S. and C.T.-C.L. carried out the analysis and wrote the article. V.C.-H.C. and C.T.-C.L. supervised study. C.T.-C.L. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors accept responsibility for the conduct of research and will give final approval.

Funding

V.C.-H.C. is partly funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (NSC 102-2314-B-040-004-MY3, MOST 105-2314-B-182-028, MOST 106-2314-B-182-040-MY3). S.-I.W. is partly funded by Mackay Memorial Hospital (MMH-106-144). R.S. is partly funded by: (a) the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London; (b) a Medical Research Council (MRC) Mental Health Data Pathfinder Award to King's College London; (c) an NIHR Senior Investigator Award; (d) the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

V.C.-H.C. has been an investigator in a clinical trial from Orient Pharma. R.S. has received research support within the past 5 years from Roche, Janssen, Takeda and GSK.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.129.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.