Violence is increasingly being viewed by the Department of Health and Human Services in the USA and other international agencies as a global public health problem. Reference Shepherd1,2 Although a neurodevelopmental basis to violent and antisocial behaviour has long been hypothesised, Reference Moffitt3,Reference Raine, Lencz, Scerbo and Ratey4 there has been no prior investigation of a structural brain abnormality reflective of early neural maldevelopment in any antisocial population. Although abnormal structure/function in multiple limbic and paralimbic structures, including the amygdala Reference Davidson, Putnam and Larson5–Reference Raine, Buchsbaum and LaCasse8 hippocampus Reference Raine, Buchsbaum and LaCasse8–Reference Raine, Ishikawa, Arce, Lencz, Knuth and Bihrle10 thalamus, Reference Raine, Buchsbaum and LaCasse8 hypothalamus, Reference George, Rawlings, Williams, Phillips, Fong and Kerich11 anterior cingulate, Reference Davidson, Putnam and Larson5 posterior cingulate, Reference Raine and Yang12 insula Reference Kiehl7,Reference Oliveira-Souza, Hare, Bramati, Garrido, Ignacio and Tovar-Moll13 and orbitofrontal cortex, Reference Blair6,Reference Oliveira-Souza, Hare, Bramati, Garrido, Ignacio and Tovar-Moll13,Reference Raine, Stoddard, Bihrle and Buchsbaum14 has been reported in adult antisocial, aggressive and psychopathic individuals, brain impairments could conceivably be a consequence of a violent lifestyle rather than a cause, and consequently it is difficult to infer causality from cross-sectional studies. Neurological research on people with head injury does, however, suggest that brain impairment may be of aetiological or pathophysiological significance with respect to psychopathy, Reference Bechara, Damasio, Tranel and Damasio15–Reference Damasio17 although genetic factors cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, initial imaging findings on structural and functional brain abnormalities in child and adolescent populations characterised by antisocial behaviour and callous–unemotional traits is suggestive of a possible neurodevelopmental basis to antisocial and psychopathic behaviour. Reference Blair6,Reference Viding and Jones18–Reference Jones, Laurens, Herba, Barker and Viding23

Cavum septum pellucidum (CSP – referred to historically as cavum septi pellucidi) is a marker for fetal neural maldevelopment. The septum pellucidum is one component of the septum and consists of a deep, midline, limbic structure made up of two translucent leaves of glia separating the lateral ventricles, forming part of the septohippocampal system. It consists predominantly of ependymal glia and fibre tracts beneath the genu and rostrum of the corpus callosum on the medial side of the frontal lobe. Reference Pansky, Allen and Budd24 Another component of the septum (the septum verum) contains the septal nuclei, lying more ventrally in the paraterminal gyrus. During fetal development at approximately the twelfth week of gestation, a space forms between the two laminae – the CSP – closure of which begins at approximately the twentieth week of gestation and ends shortly after birth (3–6 months postnatally). Reference Sarwar25 Fusion of the CSP is attributed to rapid development of the alvei of the hippocampus, amygdala, septal nuclei, fornix, corpus callosum and other midline structures. Reference Kim, Lyoo, Dager, Friedman, Chey and Hwang26,Reference Nopoulos, Krie and Andreasen27 Lack of such limbic development interrupts this posterior-to-anterior fusion, resulting in preservation of the CSP into adulthood.

There are individual differences in the degree of this neurodevelopmental abnormality; whereas some have complete closure of the cavum, others present with a small degree (>6 mm in the coronal plane) of incomplete closure. Reference Kim, Lyoo, Dager, Friedman, Chey and Hwang26,Reference Nopoulos, Krie and Andreasen27 The cause of the maldevelopment of midline limbic structures that results in CSP is largely unknown, although it is thought that prenatal alcohol exposure plays a significant teratogenic role. Reference Swayze, Johnson, Hanson, Piven, Sato and Giedd28

To test the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy, we examined the presence of CSP in antisocial and psychopathic individuals using anatomical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a community sample at risk for antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy. If antisocial personality disorder and psychopathic behaviour are partly a product of disrupted limbic neurodevelopment in the prenatal and early postnatal months, those with a CSP would be hypothesised to show more antisocial, psychopathic and criminal behaviour. The pervasiveness of the hypothesised relationship was further tested by assessing whether individuals lacking antisocial personality disorder, but who nevertheless show some degree of criminal activity, also show more evidence of CSP than non-antisocial controls.

Method

Participants

Eighty-seven participants (75 male, 12 female) were recruited from five temporary employment agencies. Reference Raine, Lencz, Bihrle, LaCasse and Colletti29 Exclusion criteria were: age under 21 or over 46, non-fluency in English, history of epilepsy, claustrophobia, pacemaker, ostensible neurological abnormality and metal implants. Ethnic representation was as follows: White (51%), Asian (6%), Hispanic (13%), African American (29%), and other (1%). Written informed consent was obtained, and the study was approved by an institutional review board. This community recruitment strategy is novel, but has the advantage that it samples individuals at high socioeconomic risk, with an eightfold increase in the yield of those with psychopathy/antisocial personality. Reference Raine, Lencz, Bihrle, LaCasse and Colletti29 To maximise confidentiality and minimise denial of self-report crime, a certificate of confidentiality was obtained from the Secretary of Health and Human Service under section 303(a) of the Public Health Act 42.

Antisocial personality disorder and criminal offending

Diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy were made by two PhD-level research assistants who had undergone a standardised training and quality assurance programme for diagnostic assessment. Reference Ventura, Liberman, Green, Shaner and Mintz30 Antisocial personality disorder was assessed using the DSM–IV criteria 31 and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID–II). Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams and Benjamin32 Eighteen participants fulfilled antisocial personality disorder criteria (17 male, 1 female). Criminal offending was assessed for all participants from criminal history record searches provided by the Bureau of Criminal Statistics, Department of Justice, yielding information on number of both police arrests (33 male, 4 female) and court convictions (26 male, 3 female).

Psychopathic personality

Psychopathy was assessed using the Psychopathy Checklist–Revised (PCL–R). Reference Hare33 A total score (range 0–40) and two subfactors (interpersonal/affective and social deviance) were derived. Reference Hare33 Internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha) was 0.90. Assessments were supplemented by five additional sources of collateral data (see Raine et al Reference Raine, Ishikawa, Arce, Lencz, Knuth and Bihrle10 for full details). Consistent with our prior work in community samples Reference Raine, Ishikawa, Arce, Lencz, Knuth and Bihrle10,Reference Raine, Lencz, Bihrle, LaCasse and Colletti29,Reference Raine, Lencz, Taylor, Hellige, Bihrle and LaCasse34,Reference Yang, Raine, Lencz, Bihrle, LaCasse and Colletti35 those with a PCL–R score of 23 or more were designated as psychopathic (30 male, 2 female).

Cognitive, trauma, psychiatric and demographic assessments

Four subtests (vocabulary, arithmetic, block design and digit symbol) of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised (WAIS–R) Reference Wechsler36 were used to estimate IQ. In total 20.4% of the sample had been exposed to life-threatening traumatic events. Because only one participant met full DSM–IV diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), degree of traumatic stress was assessed by summing scores on the five PTSD criteria of DSM–IV. Similarly, a dimensional measure of antisocial personality disorder was created by summing SCID scores on individual antisocial personality disorder symptoms. Potential psychiatric confounds (alcohol misuse/dependence, substance misuse/dependence, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, psychosis, bipolar disorder, depression) were assessed using the SCID–I and II. Head injury was defined as the number of times knocked unconscious. Reference Raine, Lencz, Bihrle, LaCasse and Colletti29 Social class was measured using the Hollingshead classification system. Reference Hollingshead37 Group scores and comparisons on psychiatric, cognitive and demographic measures are given in Table 1.

Table 1 Comparisons between control and antisocial personality disorder groups on demographic, cognitive, trauma and antisocial measures

| Control group (n = 69) | Antisocial personality disorder group (n = 18) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | Mean | s.d. | Range | % (n) | Mean | s.d. | Range | Statistic | P | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Age, years | 31.23 | 6.83 | 21–46 | 32.72 | 6.54 | 24–44 | t = 0.82 | 0.41 | ||

| Social class | 35.00 | 10.84 | 17–58 | 33.83 | 7.64 | 16–43 | t = 1.0 | 0.32 | ||

| Ethnicity, White | 56.17 (36) | 33.33 (6) | χ2 = 2.95 | 0.11 | ||||||

| Gender, male | 84.1 (58) | 94.4 (17) | χ2 = 1.52 | 0.22 | ||||||

| Cognitive | ||||||||||

| Total IQ | 99.49 | 15.91 | 66–134 | 98.44 | 12.12 | 78–118 | t = 0.8 | 0.41 | ||

| Trauma | ||||||||||

| Number of head injuries | 2.22 | 4.47 | 0–25 | 2.23 | 3.01 | 0–12 | χ2 = 0.6 | 0.73 | ||

| Traumatic stress | 2.29 | 5.29 | 0–28 | 2.72 | 5.89 | 0–20 | t = –0.27 | 0.78 | ||

| Antisocial | ||||||||||

| Psychopathy Checklist–Revised | ||||||||||

| Total scores | 15.88 | 6.43 | 5–30 | 28.65 | 6.12 | 21–40 | t = 14.8 | 0.0001 | ||

| Factor 1 | 5.32 | 3.52 | 0–16 | 10.05 | 3.56 | 4–16 | t = 8.4 | 0.0001 | ||

| Factor 2 | 7.15 | 2.97 | 0–15 | 13.70 | 2.91 | 9–18 | t = 9.2 | 0.0001 | ||

| Antisocial personality disorder score | 4.31 | 2.64 | 0–10 | 10.50 | 2.28 | 6–14 | t = 12.7 | 0.0001 | ||

| Charges | 2.86 | 10.03 | 0–53 | 6.94 | 6.52 | 0–20 | t = –1.61 | 0.11 | ||

| Convictions | 0.94 | 3.58 | 0–22 | 2.44 | 2.50 | 0–9 | t = –1.65 | 0.10 | ||

MRI

Acquisition

Structural MRIs were conducted on a Philips S15/ACS scanner (Selton, Connecticut) with a 1.5 tesla magnet. Following an initial alignment sequence of one midsaggital and four parasagittal scans (spin-echo T 1-weighted image acquisition, repetition time (TR) 600 ms, echo time (TE) 20 ms) to identify the anterior commissure–posterior commissure (AC–PC) plane, 128 3-D T 1-weighted gradient-echo coronal images (TR = 34 ms, TE = 12.4 ms, flip angle 35°, 1.7 mm slices, 256×256 matrix, field of view (FOV) 23 cm) were taken orthogonal to the AC–PC line.

CSP assessment

Image preprocessing was conducted using individual executable programs in a processing tree using the LONI Pipeline Processing Environment. Reference Rex, Ma and Toga38 Images were first reformatted as 1.0 mm slices to increase resolution for visual analysis. Anatomical boundaries for CSP were as follows: the genu of the corpus callosum defined the anterior boundary, the body of the corpus callosum defined the superior boundary, the rostrum of the corpus callosum and fornix defined the inferior boundary, and the junction of the splenium of the corpus callosum with the crus of the fornix defined the posterior boundary. The number of coronal 1 mm slices on which the CSP was present was recorded. Following the convention of other studies Reference Swayze, Johnson, Hanson, Piven, Sato and Giedd28,Reference Kwon, Shenton, Hirayasu, Salisbury, Fischer and Dickey39,Reference May, Chen, Gilbertson, Shenton and Pitman40 presence of CSP was defined as a CSP of 6 mm or greater length (n = 19; 14 male, 5 female). Scoring was performed in the anterior-to-posterior direction in the coronal view, using a simultaneous sagittal view to ensure that consistent anatomical boundaries were maintained. Scoring was conducted masked to all other participant data. Twenty-five participants were randomly selected and scored by a second rater masked to group membership and the other rater's assessment; interrater reliability of length of CSP was high (r = 0.98). A coronal illustration of CSP is provided in Fig.1.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 10 for Windows. A 2 (CSP present/absent)×2 (male/female) univariate analyses of variance design was conduced with antisocial measures as dependent variables, in addition to multivariate analyses for subfactors of psychopathy. In each analysis on the antisocial construct in question (e.g. antisocial personality disorder, psychopathy) those with, for example, antisocial personality disorder were compared with all others in the sample who did not fulfil criteria for antisocial personality disorder. All tests of significance are two-tailed. Effect sizes were calculated using η (% variance accounted for). Factor analysis using an oblimin oblique rotation was used to derived subfactors of antisocial personality disorder to assess whether CSP was more associated with aggressive/life-course features.

Results

Antisocial personality disorder

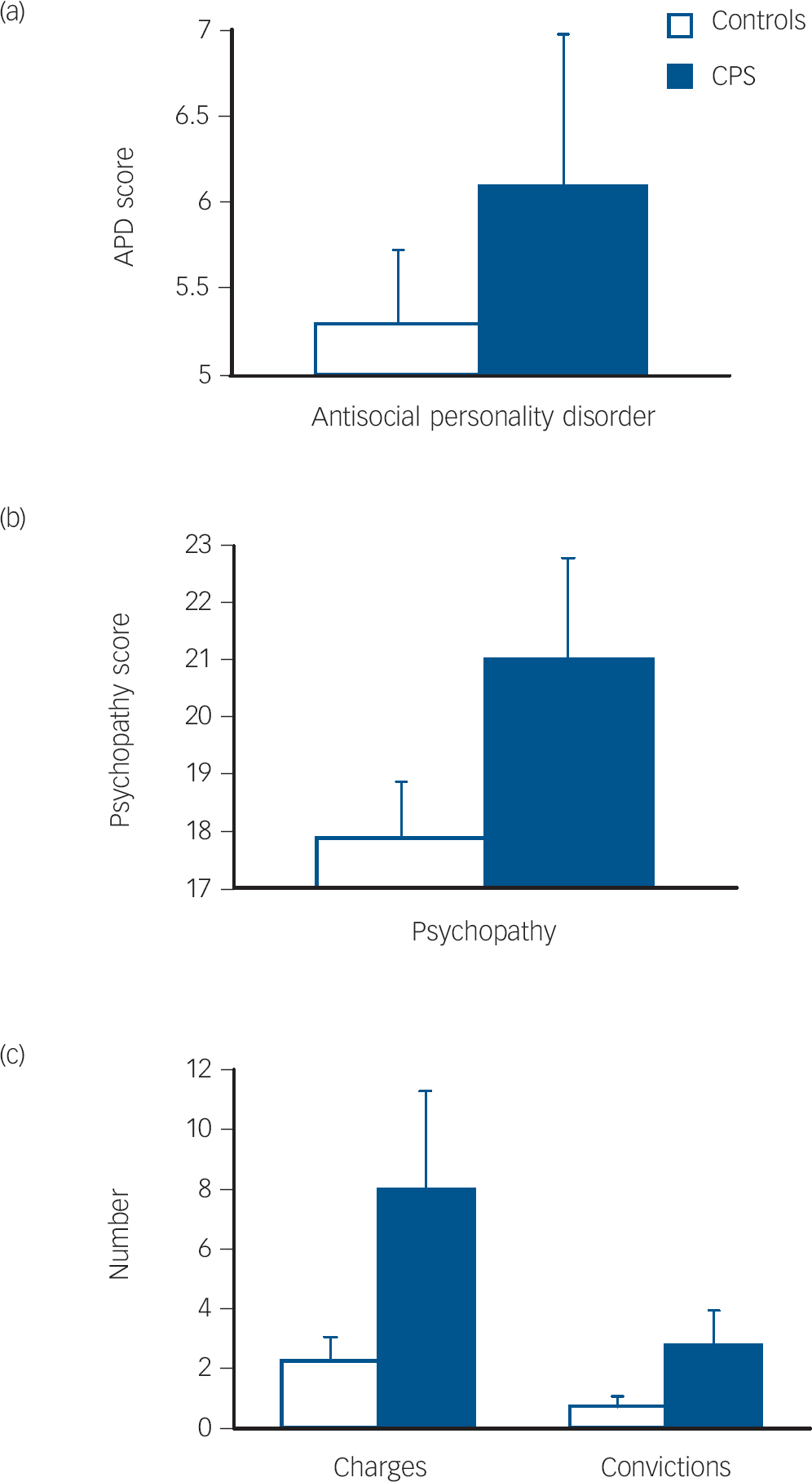

A main effect of CSP grouping indicated higher scores on antisocial personality disorder (mean 6.20) in the CSP group compared with controls (mean 5.29) (F(1,83) = 5.00, P = 0.028, η = 0.057, Fig. 2). Males had higher antisocial personality disorder scores (mean 5.29) than females (mean 0.50) (F(1,83) = 8.85, P = 0.004, η = 0.096), but there was no cavum× gender interaction (P = 0.11).

Subfeatures of antisocial personality disorder

Two subcomponents of antisocial personality disorder were derived using factor analysis. Significant (>0.30) loadings on the aggressive/life-course factor (coefficient α = 0.71) consisted of irritability/aggressiveness (0.83), reckless disregard for self/others (0.70), child/adolescent conduct disorder (0.69), failure to conform to social norms (0.64) and lack of remorse (0.33). Loadings on the deceptive–irresponsible factor (coefficient α = 0.67) were deceitfulness (0.89), consistent irresponsibility (0.77), impulsivity (0.60) and lack of remorse (0.31). The two factors intercorrelated 0.46 (P<0.001). The regression method was used to estimate factor scores for each factor.

Presence of a CSP was more related to the aggressive/life-course component of antisocial personality disorder than to deceptive–irresponsible features (Fig. 3). A main effect of CSP grouping indicated higher aggression scores in the CSP group compared with controls, F(1,80) = 5.42, P = 0.022, η = 0.063, with no CSP×gender interaction (P = 0.128). No such CSP main effect was observed for the deceptive–irresponsible factor, F(1,80) = 1.46, P = 0.229, and no CSP×gender interaction was observed (P = 0.22).

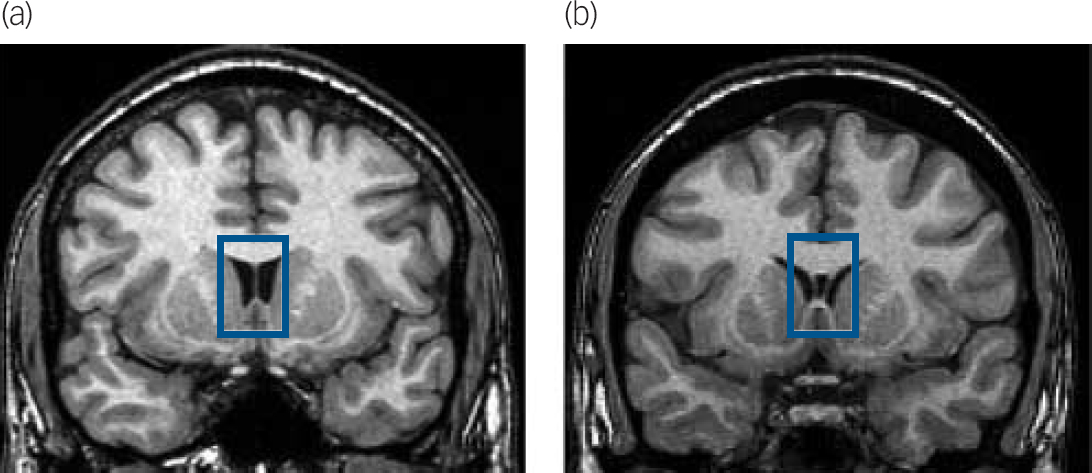

Fig. 1 Illustration of normal septum pellucidum (thin membrane separating the lateral ventricles) in a non-antisocial control (a) and the cavum septum pellucidum in an individual with antisocial personality disorder (b).

Coronal magnetic resonance image slices are at the level of the head of the anterior limb of the internal capsule, caudate, putamen, accumbens, and insula. Highlighted within the bue box is the septum pellucidum, dividing the lateral ventricles and bordered superiorly by the body of the corpus callosum and inferiorly by the fornix. The normal control (a) shows a fused septum pellucidum, whereas the participant with antisocial personality disorder (b) shows a fluid-filled cavum inside the two leaflets of the septum pellucidum.

Fig. 2 Mean scores (with standard error bars) for those with a cavum septum pellucidum (CPS) and those without CSP (controls) on measures of antisocial personality disorder (a), psychopathy (b), and criminal charges or convictions (c).

Psychopathy

A main effect of CSP grouping indicated higher psychopathy scores in the CSP group, F(1,80) = 8.21, P = 0.005, η = 0.093 (Fig. 2). A significant CSP×gender interaction indicated particularly higher psychopathy scores in females with a CSP, (F(1,80) = 4.41, P = 0.039, η = 0.052.

Subfactors of psychopathy

A multivariate analysis of variance on the two main factors of psychopathy indicated a main effect of CSP group, F(2,80) = 4.47, P = 0.014, η = 0.10, with no group×gender interaction (P = 0.10). Univariate analyses indicated higher scores in the CSP group on both the interpersonal/affective factor, F(2,80) = 4.98, P = 0.028, η = 0.06, and the social deviance factor, F(2,80) = 8.82, P = 0.004, η = 0.10 (Fig. 3).

Criminal charges and convictions

Those with a CSP present had more criminal charges and convictions than controls (Fig. 2). A multivariate analysis of variance indicated a main effect of CSP grouping on criminal charges and convictions, F(2,83) = 3.80, P = 0.027, η = 0.084. with no group×gender interaction (P = 0.14). Univariate analyses indicated significant effects both for charges (F(1,84) = 7.32, P = 0.008, η = 0.080) and convictions (F(1,84) = 6.00, P = 0.016, η = 0.067).

Fig. 3 Mean scores (z-transformed) and error bars on aggressive/life-course and deceptive–irresponsible subcomponents of antisocial personality disorder (a), and also interpersonal/affective and social deviance components of psychopathy (b) in groups with and without a cavum septum pellucidum (CPS).

CSP in those lacking antisocial personality disorder but with some criminal offending

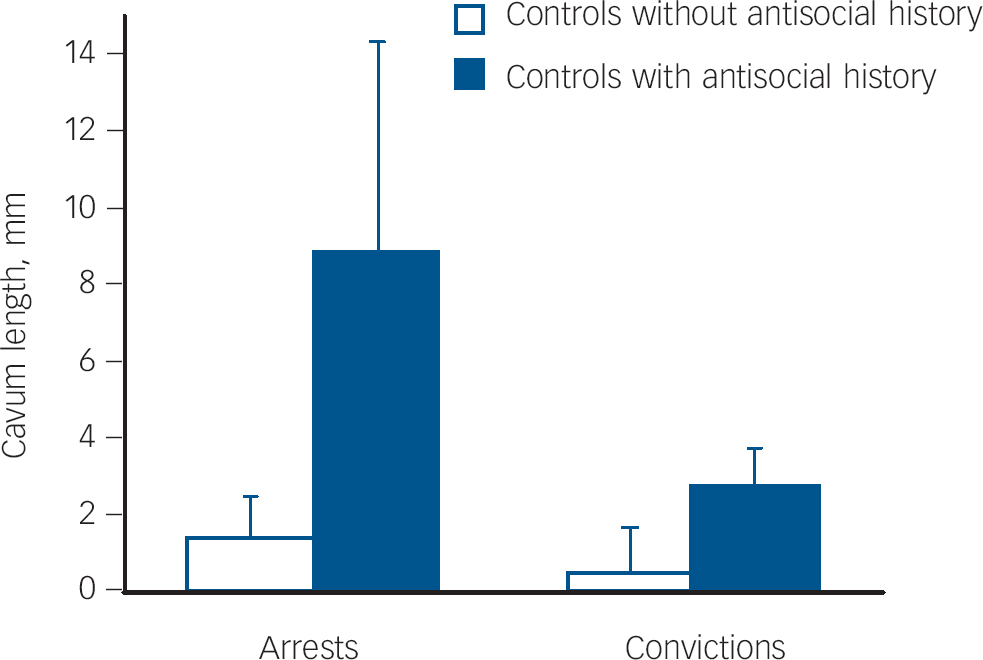

Individuals who did not have a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder, but who nevertheless had been either arrested or convicted for a crime showed more evidence of CSP. Individuals in the control group were divided into those with a criminal history of arrests/convictions, and those without such a criminal history. Participants without an antisocial personality disorder but with a history of arrests had a longer CSP than those participants without an antisocial personality disorder but without arrests, F(1,61) = 5.57, P = 0.021, η = 0.084, with no main effect for gender (P = 0.94) or arrest×gender interaction (P = 0.60, Fig. 4). Participants without an antisocial personality disorder but with a history of convictions showed a trend for a longer CSP than those participants without an antisocial personality disorder but without convictions, F(1,61) = 3.34, P = 0.073, η = 0.052, with no main effect for gender (P = 0.61) or arrest×gender interaction (P = 0.94, Fig. 4).

Potential confounders

Demographic, trauma and cognitive background data are provided in Table 1. The relationship between antisocial behaviour and CSP was independent of trauma exposure and head injury. With CSP as the grouping variable and dimensional antisocial measures as the dependent variables, main effects remained significant for antisocial personality disorder (F(1,81) = 4.89, P = 0.03, η = 0.057), psychopathy (F(1,78) = 8.16, P = 0.005 η = 0.095), charges (F(1,81) = 5.71, P = 0.019, η = 0.066) and convictions (F(1,81) = 4.47, P = 0.038, η = 0.052) after simultaneously controlling for both post-traumatic stress and head injury.

We also tested the possibility that alcohol and substance dependence, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal personality), psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective, schizophreniform, delusional, brief psychotic episode, psychosis not otherwise specified) and mood disorders (bipolar, major depression) may be comorbid disorders accounting for the CSP–antisocial relationship. After simultaneously entry of all these covariates, the main effects of CSP remained significant for antisocial personality disorder F(2,70) = 25.27, P = 0.001, η = 0.41), psychopathy (F(2,67) = 64.63, P = 0.0001, η = 0.659) and convictions (F(2,70) = 3.46, P = 0.037, η = 0.09), although the effect for charges was rendered marginally significant (F(2,70) = 2.44, P = 0.094, η = 0.065) being reduced in size by 25%.

Fig. 4 Mean length (mm) of cavum septum pellucidum with standard error bars in controls lacking a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder but who nevertheless have either been charged (a) or convicted (b) for criminal offences compared with controls lacking both antisocial personality disorder and charges/convictions.

To further assess the possible influence of these factors, potential interaction effects between these confounds and CSP were tested for all antisocial dependent measures. No significant interactions were obtained (P>0.075).

We also assessed whether age, education level, social class and total brain volume could confound relationships between CSP and antisocial variables. After entering these covariates simultaneously in a block, the main effect of CSP remained significant for antisocial personality disorder (F(1,79) = 4.65, P = 0.034, η = 0.056), psychopathy (F(1,77) = 4.147, P = 0.045, η = 0.051), charges (F(1,80) = 6.31, P = 0.014 η = 0.073) and convictions (F(1,80) = 12.37, P = 0.001, η = 0.134). Furthermore, there were no interactions between these variables and CSP in relation to the four antisocial measures (P>0.138).

Discussion

Main findings

Individuals with a CSP have significantly higher levels of antisocial personality, psychopathy, criminal charges and convictions compared with those lacking a CSP. The pervasiveness of the association was further demonstrated by the same finding within the clinical control group; those lacking a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder but who nevertheless were charged with a criminal offence showed a larger CSP than controls lacking both an antisocial personality disorder diagnosis and criminal charges. Findings could not be attributable to trauma exposure, head injury or comorbid psychiatric conditions. This convergence suggests that findings are relatively robust, and that a broad spectrum of antisocial behaviours ranging from psychopathy to antisocial personality disorder to criminal offending is associated with fundamental differences in degree of limbic neural maldevelopment. Findings appear to be the first to provide evidence for a neurodevelopmental brain abnormality in antisocial individuals, and support the hypothesis that early maldevelopment of limbic and septal structures predisposes to antisocial behaviours.

Neurodevelopmental mechanisms

In humans, impairment to the septum has long been hypothesised to result in psychopathic, antisocial and disinhibited behaviour. Reference Gorenstein and Newman41 Because septal nuclei are contained in the septum pellucidum, morphological disruption to this structure would impair septal functioning and its regulatory connections to other limbic structures. In animals, the septum is critically involved in the regulation of aggression. Reference Potegal, Blau and Glusman42,Reference Siegel, Bhatt, Bhatt and Zalcman43 Septal stimulation in a wide range of animals (rats, hamsters, mice, cats and monkeys) inhibits predatory aggression, Reference Clemete and Chase44 whereas lesions to the septum result in increased aggression and disinhibited behaviour. Reference Clemete and Chase44,Reference Veenema and Neumann45 In both highly aggressive mice and rats, reduced neural activation of the lateral septum as indicated by reduced c-fos expression results in disinhibition of the anterior hypothalamus and hypothalamic attack area, resulting in enhanced activation of parts of the periaqueductal grey area that in turn enhances attack behaviour. Reference Veenema and Neumann45 Of note, CSP was associated with aggressive features of antisocial personality disorder but not with non-aggressive features, indicating particular relevance of septal disruption to aggression in humans.

Neural maldevelopment of the septum is hypothesised to result in increased antisocial, aggressive and psychopathic behaviour through impaired bonding and attachment and a lack of prosocial affiliative behaviour in antisocial personality disorder, both of which have been linked to septal functioning. The lateral septal nuclei (an important oxytocin receptor-binding site) has been implicated in social attachment and bonding behaviours in animals. Reference Insel and Young46 Antisocial psychopathic behaviour has been classically viewed as having its roots in early maternal deprivation during a critical period for bonding and attachment. Reference Bowlby47,Reference Rutter48 Disruption to the septal system could consequently result in a failure to bond to caregivers (even in the absence of maternal deprivation) resulting in affectionless, psychopathic-like, antisocial behaviour. Furthermore, recent imaging research on prosocial behaviour in humans has demonstrated septal activation when making altruistic donations, with number of donations also significantly correlated with increased septal activation. Reference Moll, Krueger, Zahn, Pardini, Oliveira-Souzat and Grafman49 The fact that CSP was related to the interpersonal/affective feature of psychopathy together with recent work showing that the emotional detachment factor of psychopathy is related to lack of both early maternal and paternal care Reference Gao, Raine, Chan, Venables and Mednick50 gives rise to the hypothesis that psychopathy and life-course antisocial personality has a basis in neurodevelopmental abnormality in the limbic system.

The hypothesis that psychopathy and antisocial personality partly reflect fetal neural maldevelopment of the limbic system is not only consistent with cross-sectional findings from prior adult brain imaging studies of aggressive and violent individuals Reference Davidson, Putnam and Larson5,Reference Kiehl7,Reference Raine, Buchsbaum and LaCasse8,Reference Oliveira-Souza, Hare, Bramati, Garrido, Ignacio and Tovar-Moll13 but is also broadly consistent with prospective longitudinal studies on babies, infants and young children showing that prenatal nicotine and alcohol exposure, Reference Brennan, Grekin and Mednick51,Reference Streissguth, Bookstein, Barr, Sampson, O'Malley and Young52 prenatal malnutrition Reference Neugebauer, Hoek and Susser53 and early postnatal malnutrition Reference Liu, Raine, Venables, Dalais and Mednick54 are associated with long-term outcomes for antisocial and violent behaviour. All of these negative environmental events affect the developing brain, and some of these have been hypothesised to give rise to the midline limbic maldevelopment that in turn results in CSP. Reference Swayze, Johnson, Hanson, Piven, Sato and Giedd28 These prior studies together with current findings suggest that factors affecting brain development during prenatal and very early postnatal periods may predispose to antisocial and aggressive behaviour. An advance that the current CSP findings add to prior imaging findings lies in the fact that because CSP is formed prior to the first 6 months of life, Reference Sarwar25 brain maldevelopment precedes the onset of criminal careers and is consequently hypothesised to be less likely a product of psychosocial and lifestyle influences that can be confounds in other adult imaging studies.

It is important to recognise that psychopathy, antisocial personality and criminal offending are not interchangeable conceptually, representing overlapping but distinct constructs. The fact that CSP is related to all of these antisocial constructs suggests a neurodevelopmental basis to a broad spectrum of antisocial behaviours that is shared by these overlapping constructs. This neurodevelopmental basis is not, however, shared with other externalising behaviour problems, including alcohol and substance misuse, because the CSP–psychopathy/antisocial relationship remained significant after controlling for these psychiatric confounds. Factors other than those reflected by CSP must inevitably give rise to the more distinguishing features of psychopathy, antisocial personality disorder and crime. A further caveat is that although CSP is known to be in place by 6 months of age, longitudinal research is required to further test the limbic neural maldevelopment hypothesis of this cross-sectional study. One recent prospective longitudinal study showing that poor fear conditioning (a marker for poor amygdala functioning) at age 3 years predicts crime at age 23 years suggest a neurodevelopmental contribution to crime causation. Reference Gao, Raine, Venables and Mednick55 Finally, although one analysis indicated a group×gender interaction indicating that CSP was particularly associated with psychopathy in females, this interaction must be treated with caution because no such interaction was observed for either psychopathy subfactors or for any other antisocial measure.

Clinical implications

In conclusion, the association between cavum septum pellucidum and the spectrum of antisocial behaviours supports a neurodevelopmental hypothesis of antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy. If serious offending is in part neurodevelopmentally determined, successful prevention efforts would be most effective if they began prenatally. One such biosocial prenatal programme that targeted maternal health factors resulted in significant reductions in juvenile delinquency 15 years later. Reference Olds, Henderson, Cole, Eckenrode, Kitzman and Luckey56 This programme, which aimed to reduce smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, might have protected against CSP and associated limbic maldevelopment because prenatal alcohol use is associated with CSP. Reference Swayze, Johnson, Hanson, Piven, Sato and Giedd28 Similarly, one experimental intervention that enhanced the early environment of young children from ages 3–5 years with better nutrition, more physical exercise and cognitive stimulation has been shown to both improve brain functioning at age 11 Reference Raine, Venables, Dalais, Mellingen, Reynolds and Mednick57 and reduce criminal offending at age 23 years by 34%. Reference Raine, Mellingen, Liu, Venables and Mednick58 Such preschool programmes would not be expected to reduce the earlier development of CSP but would be expected to ameliorate limbic maldevelopment because physical exercise is known to promote neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Reference van Praag, Kempermann and Gage59 Clinical, social and educational services that improve prenatal and perinatal health in underserved at-risk mothers may conceivably prevent limbic neurodevelopment, reduce antisocial personality disorder and violence, and partially alleviate this major public health problem. Finally, because it has been argued that CSP is a heritable contribution Reference May, Chen, Gilbertson, Shenton and Pitman40 and because approximately 50% of the variance in adult antisocial behaviour is heritable Reference Moffitt60 (with higher heritability in children with callous–unemotional traits), Reference Viding, Jones, Frick, Moffitt and Plomin61 genetic influences on limbic maldevelopment in antisocial personality and psychopathy must also be considered alongside environmental influences.

Funding

This study was supported by an Independent Scientist Award (K02 MH01114-01) and grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (5 RO3 MH50940-02) and the Wacker Foundation to A. R.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jennifer Bobier, Nicole Diamond, Kevin Ho, Lori Lacasse, Todd Lencz, Shari Mills and Pauline Yaralian for assistance in data collection.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.