A considerable body of research has examined the impact of natural disasters on psychological health. Most of this work has focused on earthquakes and accompanying tsunamis, or major weather events such as floods and hurricanes, and illustrated the long-term psychological toll of these disasters.Reference Beaglehole, Mulder, Frampton, Boden, Newton-Howes and Bell1,Reference Oishi, Kimura, Hayashi, Tatsukid, Tamurae and Ishiif2 Studies have considered associations between distress and recovery and existing vulnerabilities, with work following earthquakes in JapanReference Miura, Nagai, Maeda, Harigane, Fujii and Oe3 and New ZealandReference Fergusson, Horwood, Boden and Mulder4 showing a positive association between pre-incident psychiatric disorders and later distress. Other work has indicated associations between post-disaster exposure, demographic factors and distress: family and housing loss were associated with greater distress following a hurricane,Reference Lowe, Sampson, Gruebner and Galea5 and women suffered greater post-traumatic stress following the 2004 South-East Asian tsunami.Reference Nygaard and Heir6 Subsequent resources and behaviours, such as the provision of social supportReference Matsuyama, Aida, Hase, Sato, Koyama and Tsuboya7 and the maintenance of daily activities,Reference Fukuda, Morimoto, Mure and Muruyama8–Reference Parks, Drakeford, Cope and Slack10 have also been shown to be protective against mental illness across different natural disasters, whereas temporary prefabricated housing was associated with greater distress following the Niigata-Chuetsu earthquake.Reference Kuwabara, Shiori, Toyabe, Kawamura, Koizumi and Ito-Sawamura11 However, much of the data collected has been cross-sectional, or has followed modest samples over time.Reference Beaglehole, Mulder, Frampton, Boden, Newton-Howes and Bell1 Furthermore, work has been primarily conducted at a single level, despite evidence that losses and opportunities are unevenly distributed across communities following disasterReference Lowe, Sampson, Gruebner and Galea5,Reference Matsuyama, Aida, Hase, Sato, Koyama and Tsuboya7 and that shared environments are critical to the accumulation of resources over time.Reference Hobfoll, Stevens and Zalta12 Indeed, city-wide maintenance or enhancement of activities post-disaster provide positive opportunities that can ameliorate the disruption often experienced after a disaster.Reference Fukuda, Morimoto, Mure and Muruyama8,Reference Hou, Hall, Hobfoll, Morina and Nickerson9 Drawing on two substantial data-sets, collected by Miyagi Prefecture in the 6 years following the Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima nuclear leak (hereafter, the Great East Japan Earthquake), we conducted longitudinal multilevel analyses examining associations between survivors' psychological distress and time (level 1), previous psychiatric disorders, disaster exposure, demographics, and individual support and activity (level 2), and wider, city-level activity levels and social support (level 3). Combining these individual- and social-level factors across two large samples allowed for a rare analysis of the differential influences of these factors over time.

Method

Data sources and participants

We report results from two prospective cohort studies examining predictors of psychological distress across time. These studies used ongoing panel data collected by the health department of Miyagi Prefecture from all registered earthquakes in Miyagi Prefecture to examine predictors of longitudinal health status from Miyagi-based survivors of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Details from the first stages of this data collection have been reported elsewhere.Reference Matsuyama, Aida, Hase, Sato, Koyama and Tsuboya7,Reference Kusama, Aida, Sugiyama, Matsuyama, Koyama and Sato13 Following the earthquake all survivors living in Miyagi Prefecture were randomly assigned to either private rented or prefabricated housing, paid for by the prefecture. Questionnaires were initially distributed to 12 868 families living in private housing in 35 municipalities (wave 1, from December 2011) and 15 979 families resident in prefabricated housing in 10 municipalities (wave 2, from September 2012). Respondents returned questionnaires through (postal) mail or to administrative offices. The prefecture allocated data linkage codes to respondents according to name, date of birth, gender and pre-disaster address, allowing individuals to be identified across waves. Subsequently, the prefecture deleted personal information to form an anonymised data-set for our analyses. Ethical approval for both samples was obtained from the prefecture as well as the ethics committees of Warwick and Tohoku Universities. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

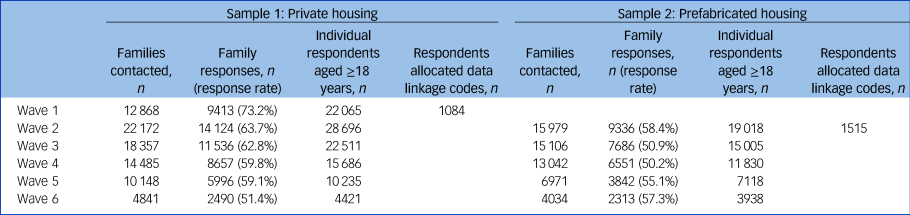

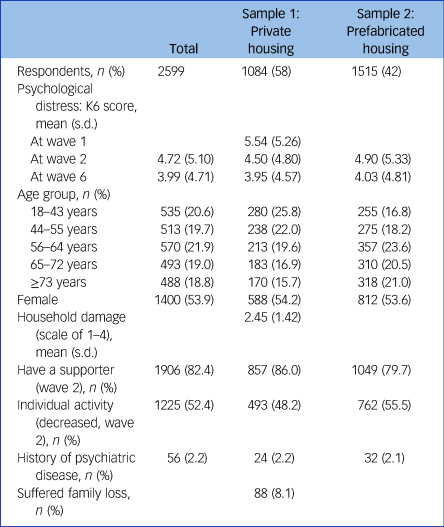

We used two related samples, distinguished by timing and the housing arrangements of participants. The first sample included data from survivors in privately rented housing (n = 1084 for all six waves). The second sample was from survivors living in prefabricated housing (n = 1515 for five waves). Table 1 reports responses per wave, by sample; Table 2 shows sample baseline characteristics. Response rates ranged from 50 to 70% over the waves. Supplementary Figs 1 and 2, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.251, describe data retention; supplementary Table 1 gives survival analyses, contrasting those who did or did not respond to all waves. Those who moved were lost to follow-up, thus number of households who submitted responses decreased over the years.

Table 1 Responses per wave by sample

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of respondents

K6, six-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.Reference Kessler, Andrew, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek and Normand15

Measures

The measures used were taken from previous work on earthquakes in Japan.Reference Miura, Nagai, Maeda, Harigane, Fujii and Oe3,Reference Matsuyama, Aida, Hase, Sato, Koyama and Tsuboya7 All participants provided their gender, age (at time 2: grouped into quintiles), current city of residence and whether or not they had someone to listen to their concerns (yes/no). They also indicated previous history of psychiatric illness (yes/no) and level of activity post-earthquake (less versus the same or more). City-level indicators of support and activity among our samples were aggregated using individual scores; consistent with previous multilevel work after the earthquake we included both individual- and community-level scores simultaneously in our models.Reference Matsuyama, Aida, Hase, Sato, Koyama and Tsuboya7 We drew data from 30 cities for sample 1, 37 cities for sample 2, all located in Miyagi Prefecture. We adjusted for the size of some of the cities by applying Bayesian estimations to provide more stable community-level variables by using EB Estimator for Windows for the Poisson-Gamma Model software.Reference Takahashi14 In the first sample only we assessed the use of a range of supporters (spouse, child, sibling, friend, each yes/no): because of the average age of the sample (32.6% were aged over 65) we excluded support from elderly family members. For this sample only, respondents were also asked whether they had lost a family member during the earthquake/tsunami (yes/no) and level of house damage (four-point scale, from ‘none’ to ‘complete collapse’).

Our outcome variable (psychological distress) was measured using the Japanese version of the six-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6),Reference Kessler, Andrew, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek and Normand15 a self-report scale intended to detect non-specific psychological distress and widely employed in Japan.Reference Suzuki, Yabe, Yasumura, Ohira, Niwa and Ohtsuru16,Reference Misawa, Ichikawa, Shibuya, Maeda, Hishiki and Kondo17 Items were scored on five-point scales ranging from 0 (no distress) to 4 (maximum stress), with possible total scores ranging from 0 to 24. Scores of 8–12 indicate probable mild to moderate mental illness and scores of 13–24 indicate severe mental illness. The scale showed good reliability in our data (overall Cronbach's α=0.91).

Statistics

For each sample we report findings for all respondents aged ≥18 years who completed all items of the K6 and all waves of the data collection (six waves for the private-housing sample, five waves for the prefabricated-housing sample). For each sample we conducted multilevel linear modelling using SAS software v. 9.4 for Windows (PROC MIXED procedure) with maximum likelihood estimation. The wave variable served as a level-1 predictor, variables at individual level (e.g. sex) as level-2 predictors, and variables at city level (e.g. averaged level of support) as level-3 predictors. All reported P-values are two-sided.

We compared the efficacy of models using Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) statistics. For each sample we first examined a baseline (random intercept only) model, which allowed us to perform a step-by-step model comparison and compute variance (percentages) for later models. Compared with the baseline model, model 1 added the predictor wave (as a fixed effect) in addition to the effect of a random intercept. Model 2 added level-2 variables alongside wave. Model 3 included all level-3 terms (fixed effects only) but no interactions. Model 4 tested whether the effect of wave varies across individuals (random coefficient model); we considered moderator (cross-level interaction) effects of this in model 5. Model 6 included random intercepts at both level 1 and level 2, comparing this to a baseline model with random intercept at level 1. The poorer fit of the final model precluded the need to further model random effects at level 2. We compared the baseline model with models 1–5, computing the variance explained at each level for each model.

For our private-housing sample only (sample 1), we also reported an additional two-level random-effect model for the association between individual supporters and psychological distress, over time.

Results

In total, 25.1% of respondents reported indications of moderate mental illness in wave 1 (2011; n = 969), declining to 16.9% at wave 6 (2016; n = 2263); 8.5% reported risk of severe mental illness in 2011, 4.8% in 2016; 8.1% (n = 88 at baseline wave 1) of those living in private housing reported having had lost a family member and 52% (n = 564) had suffered partial or complete destruction of their house as a consequence of the earthquake/tsunami.

Survival analyses compared those who completed all waves of the survey with those who participated in a specific wave, on psychological distress (supplementary Table 1). There were no differences between completers of all waves and completers of a specific wave, with the exception of wave 1 (sample 1), where those responding throughout the study reported greater distress.

Multilevel analyses

Because we conducted analyses over different periods of time, and included additional variables in our first sample, we conducted separate analyses for the two samples.

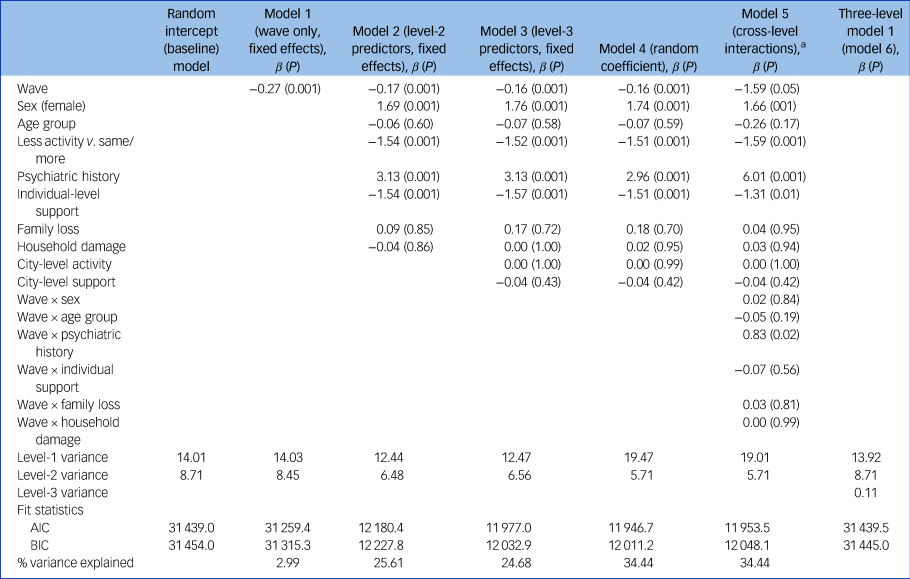

Sample 1 (six waves of private-housing residents, 2011–2016)

Multilevel findings (Table 3) show distress declining over time (model 1: random intercept variance β = −0.27, P < 0.001). For fixed-level models 2 and 3 the significance of wave remains, as does being female, having a psychiatric history and (lacking) individual support (all positively associated with distress). Neither age, family loss or household damage were related to distress, nor were city-level support or activity levels. Allowing for random coefficients (model 4) increased overall variance explained by 9.47%; however, introducing cross-level interactions (model 5) did not improve model fit.

Table 3 Multilevel model of psychological distress over time: sample 1, living in private housing 2011–2016

AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion.

a. Cross-level interactions (model 5) are retained for illustrative purposes but did not add to the model. Repeating this model with city-level interactions provided an inferior fit, with no city-level interactions; this analysis is available from the first author.

Subsidiary analyses considered associations between support from different supporters in the year following the earthquake and psychological distress, across waves (supplementary Table 2). Initial support from the spouse, and to a lesser extent friends, was most strongly associated with lower psychological distress, controlling for psychiatric history, wave, gender and age. Further analyses (available from the first author) revealed no interaction between wave and individual support types, suggesting a similar pattern for each supporter across time.

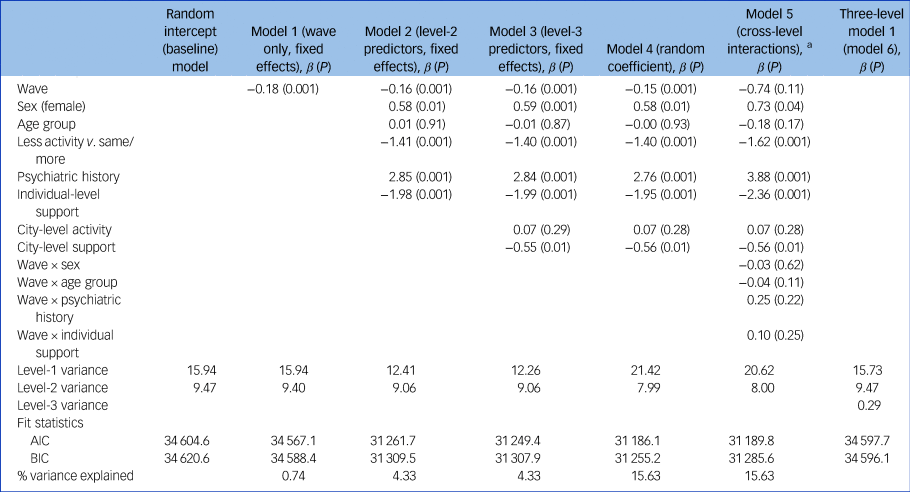

Sample 2 (five waves of prefabricated-housing residents, 2012–2016)

In this sample distress also decreased over time, with the same additional predictors (gender, individual activity, social support and psychiatric history) remaining significant across models 2–4, although overall variance explained is smaller for each sample (Table 4). For this sample only higher levels of city-level support were associated with less distress (P < 0.01), but there was no city-level effect for activity (P = 0.28). As with sample 1, cross-level interactions produce no improvement in variance explained.

Table 4 Multilevel model of psychological distress over time: sample 2, living in prefabricated housing 2012–2016

AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion.

a. Cross-level interactions (model 5) are retained for illustrative purposes but did not add to the model. Repeating this model with city-level interactions provided an inferior fit, with no city-level interactions; this analysis is available from the first author.

Discussion

Natural disasters such as the Great East Japan Earthquake can have considerable implications for mental health, with consequences likely to fluctuate over time and across communities. Although there is a substantial literature on resilience and recovery following such events in Japan and elsewhere, we present what we believe is the first attempt to ascertain drivers of post-disaster distress over a substantial period of time, with a broad population sample of survivors and across multiple levels of analysis. Two independent longitudinal samples of earthquake survivors, living in different housing conditions and with more than 1000 participants in each, produced both consistent and sample-specific findings. In both samples psychological distress declined over time: (lack of) pre-disaster psychological illness, (male) gender and post-disaster support and activity maintenance, were negatively associated with psychological distress. Age effects, however, were small. City-level support was negatively associated with distress but only among residents of prefabricated homes; for our privately housed survivors, support from friends and the spouse, but not children or siblings, negatively predicted psychological distress across waves. These findings, we believe, address important theoretical questions about the impact of both individual and sociocultural factors on mental health. They also have significant clinical implications for practitioners in the field, and the organisation and distribution of resources following a major disaster.

Across both samples we found relatively low levels of psychological distress, particularly considering the high levels of household destruction suffered by our samples and the already high levels of distress recorded in Miyagi Prefecture prior to the earthquake.Reference Misawa, Ichikawa, Shibuya, Maeda, Hishiki and Kondo17 Studies in Fukushima over a period of 3 years after the Great East Japan EarthquakeReference Oe, Takahashi, Maeda, Harigane, Fujii and Miura18 and in Niigata in the 5 years consecutive to the 2004 earthquake in that prefectureReference Nakamura, Kitamura and Someya19 showed decreases in distress over time, and in our prospective multilevel models time was also the major contributor to variance in post-disaster distress. As elsewhere, effects for gender and previous psychiatric disorders persisted across waves: in previous studies women carried the heavier emotional burden post-disaster,Reference Nakamura, Kitamura and Someya19 potentially as a result of their lesser access to positive social support.Reference Wind and Kromproe20 Age effects, however, were minimal, reflecting mixed findings in the literature: there was no age effect among Norwegian survivors of the 2004 South-East Asian tsunami,Reference Nygaard and Heir6 but older age was associated with higher distress following a major hurricane.Reference Lowe, Sampson, Gruebner and Galea5 Despite the potential vulnerability of older refugees it is possible that experiences of previous earthquakes inoculated against further distress in our samples. Consistent with previous research on both received and perceived social support following other earthquakes, hurricanes and floods,Reference Norris, Friedman, Watson, Byrne, Diaz and Kaniasty21 individual-level support was important for psychological health even when controlling for demographic factors. Previous research typically sums social support across supporters: in our analyses it was support from spouses and friends that was most frequently noted by our respondents (from spouses, 26%; friends, 23%), with this support also the most protective against psychological distress. Conservation of resources theory (COR) argues that maintenance of daily activities after a disaster can ameliorate the ‘lifeway disruptions’ frequently associated with post-disaster recovery.Reference Parks, Drakeford, Cope and Slack10,Reference Hobfoll, Stevens and Zalta12 Although there was no notable change in levels of activity post-disaster, with approximately half of our survivors maintaining their pre-disaster activity levels across waves (48–51%, by sample), positive associations between individual activity and low distress suggested that the maintenance of stable daily activities is important for resilience over time.Reference Hou, Hall, Hobfoll, Morina and Nickerson9 However, contrary to COR, actual loss of family members or physical housing did not have a significant impact on psychological distress, when considered alongside demographic, social support and activity indicators.

Relatively little research has combined individual- and community-level factors on post-disaster recovery, although both are important in avoiding the cycles of loss and threats to resources that often accompany disaster.Reference Parks, Drakeford, Cope and Slack10 In a study examining post-traumatic symptoms and depression following Hurricane Sandy in the USA, community-level factors (social capital) interacted with individual-level exposure to influence resilience.Reference Lowe, Sampson, Gruebner and Galea5 In a further example, using data from the first two waves of our sample living in prefabricated housing,Reference Matsuyama, Aida, Hase, Sato, Koyama and Tsuboya7 individual-level support and social participation combined with community-level support to predict psychological distress 1 year later. In contrast, other work on flooding has suggested that the effects of individual-level resources may be subsumed by community-level social support.Reference Wind and Kromproe20 In our larger longitudinal analysis we find a unique effect for support at the city level, but only among residents of prefabricated (rather than private) housing. This finding may reflect the greater concentration of survivors into one area among members of this housing sample – sharing a community setting may be critical for leveraging social capital.Reference Hou, Hall, Hobfoll, Morina and Nickerson9 Despite the challenges of living in prefabricated housing, with its greater noise and extreme temperatures,Reference Kusama, Aida, Sugiyama, Matsuyama, Koyama and Sato13 the close proximity of these homes can make it easier for those in these dwellings to obtain both municipal and voluntary support.Reference Kusama, Aida, Sugiyama, Matsuyama, Koyama and Sato13 In addition, those in close proximity settings such as the prefabricated housing in our study benefit from being able to meet and work together to resolve common problems,Reference Matsuyama, Aida, Hase, Sato, Koyama and Tsuboya7 making such settings ‘competent communities’Reference Hobfoll, Stevens and Zalta12 with ‘collective efficacy’,Reference Bonanno, Romero and Klein22 in which there are opportunities for involvement and social cohesion. In more dispersed communities (such as in our private-housing sample), collective support can be difficult to sustain, with such support taxing (and therefore less beneficial) for both individuals and broader societal organisations.Reference Lowe, Sampson, Gruebner and Galea5 At the same time, our findings show the continuing significance of individual-level support, above and beyond community-level aid. This underlines the importance of considering both individual- and community-level variables together, and recognising the complex interplay between the two.Reference Bonanno, Romero and Klein22

Limitations and future research

We recognise a number of limitations to our work. First, our design did not allow us to identify pre-disaster characteristics of our populations beyond self-reports of prior psychiatric disorders. A range of pre-disaster factors are likely to be important in predicting resilience to disasters, with pre-disaster support reducing exposure to the threat, as well as encouraging individuals to stay rather than leave an area following a disaster.Reference Lowe, Sampson, Gruebner and Galea5 Within the broader disaster literature these include the presence of children, pre-existing parental distress and personality factors.Reference Norris, Friedman, Watson, Byrne, Diaz and Kaniasty21 Our use of a simple binary indicator of pre-existing mental illness failed to allow us to identify the nature of this illness. Second, data were self-reported and we relied on a single measure of distress (the K6). Although widely used in Japan, the K6 is not necessarily equivalent to clinical interviews for diagnosing risk of mental illness. Third, we lacked several important socioeconomic details, such as income and education, and our brief measurement of social support did not allow us to identify the quality of this support. Our data did not allow us to consider further stressors between waves, such as further family loss. The older age of our samples meant that it was not meaningful to include employment rates in our analysis: both employment and occupation may be significant predictors of distress following disaster.Reference Parks, Drakeford, Cope and Slack10 Fourth, our first wave of data did not include respondents from prefabricated housing, limiting us to a five-wave analysis in sample 2. Finally, one reason for our failure to find further associations between city-level variables and distress may be because the units of measurement in our study (cities) were comparatively large. Further research could model the impact of a variety of community indicators, using communities with a range of sizes.

We identify several avenues for future work. While mass stressors can have significant negative effects, such trauma has also been associated with personal growth across three different types of disaster.Reference McMillen, Smith and Fisher23 Given the significance of social support for psychological distress, future research should seek to assess in more detail mechanisms for such support and growth over time, taking into account the possible enhancement of relationships both within families and across communities. Second, our work focused on natural disasters: we also need to consider the significance of factors such as family/housing loss over time following more deliberate actions (including terror attacks and civil conflicts). Third, we were not able to conduct prefecture-level analyses. Given that high levels of distress have been reported elsewhere in JapanReference Fushimi, Saito, Shimizu, Kudo, Seki and Murata24 in non-clinical populations not facing an imminent disaster, it is possible that the findings reported in Miyagi are unrepresentative. Indeed, initial evidence suggests particularly high rates of psychological distress among survivors from Fukushima Prefecture, arising from a combination of public stigma, disruption to social networks and family dissension over any decision to return.Reference Goodwin, Takahashi, Sun and Ben-Ezra25 Given uncertainties about the long-term health prospects for those affected by such events, further work should explore prospective changes in psychological distress following ambiguous, and potentially stigmatic, events (such as radiation leaks or chemical spills).

Clinical implications

We believe that our findings have several significant clinical implications. First, prevalence of psychological distress in our study was relatively low (overall, 8.5% were at risk of severe mental illness). There is evidence that prevalence of severe mental illness was already high in Miyagi Prefecture in the months before the Great East Japan Earthquake (estimated at 9.1% in February 2011), and was therefore not necessarily significantly augmented by these subsequent events.Reference Misawa, Ichikawa, Shibuya, Maeda, Hishiki and Kondo17 The lack of significant increase in mental illness may partly result from a culturally fatalistic belief in shouganai (‘it cannot be helped’), often attributed to an affected population's familiarity with natural disasters in Japan. It is also consistent with the wider finding, across the research literature on mass trauma, that only a minority of those affected are severely distressed.Reference Bonanno, Westphal and Mancini26 Clinicians need to be aware of the risk of assuming high levels of distress following a traumatic event and should focus their attention primarily on those most likely to be at risk. Second, our findings challenge assumptions that family or household loss is necessarily a major factor in the prediction of psychological distress. Instead, other variables, such as the availability of social support, may be equally important when designing and implementing interventions, suggesting a ‘forward-looking’ orientation as individuals seek to rebuild their lives following the disaster. Forms of support are, however, not all equal, with provision of support from friends and spouses likely to be more efficacious than that from others (such as siblings). The adequate provision of couple and family therapy may become of particular importance following a disaster. Third, there has been little clinical evidence on the long-term influence of housing type on recovery after a disaster. Our data suggest that community support is particularly significant for those living in temporary residences, and continuing interventions to provide support in temporarily located communities may be of particular import for psychological health. This might involve dedicated outreach services targeting those living in these new communities, enabling community residents to meet together to work to resolve common problems. It also suggests the need for opportunities for such social gatherings among those more widely dispersed – some subgroups (e.g. men, who are generally less willing to seek support) may particularly benefit from such interventions.Reference Matsuyama, Aida, Hase, Sato, Koyama and Tsuboya7 Fourth, those with pre-existing psychiatric disorders were more likely to report psychological distress. Ecological analyses conducted shortly before the earthquake suggest particular vulnerability among in-patients with mental illness.Reference Misawa, Ichikawa, Shibuya, Maeda, Hishiki and Kondo17 Given that many of these institutions were severely disrupted during the Great East Japan Earthquake, special care must be taken to support those with enduring clinical vulnerabilities in newly dispersed communities. Where records survive, clinicians may seek out those with pre-existing diagnoses and offer targeted support if required. Finally, evacuees may benefit from increased opportunities to participate in physical activity; daily routines form part of the fabric of everyday life but are too frequently neglected in investigating links between trauma and health.Reference Hou, Hall, Hobfoll, Morina and Nickerson9 Significant shared trauma makes it often difficult to maintain daily activities such as the leisure practices key to the fabric of daily life – and the maintenance of positive mental health.Reference Hou, Hall, Hobfoll, Morina and Nickerson9 The identification and potential provision of such activities for meaningful daily engagement may form an important part of a clinician's armoury following major trauma. Governmental and other formal and informal agencies need to be aware of these persistent influences in planning longer-term aid and interventions, even a number of years after a major disaster.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Leverhulme Foundation (RPG-2016-188). The funders of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Miyagi Prefectural officers and all those who participated in all waves of the study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the views of Miyagi Prefecture. The authors also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Data availability

Data access was given under agreement by Miyagi Prefecture to R.G., K.S. and S.S. for the purposes of this analysis.

Author contributions

R.G., K.S. and S.S. conducted the data analyses; J.A. aided in interpretation. J.A. and M.B.-E. helped conceptualise the study and reviewed and revised the report. All authors approved the final manuscript submission.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.251.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.