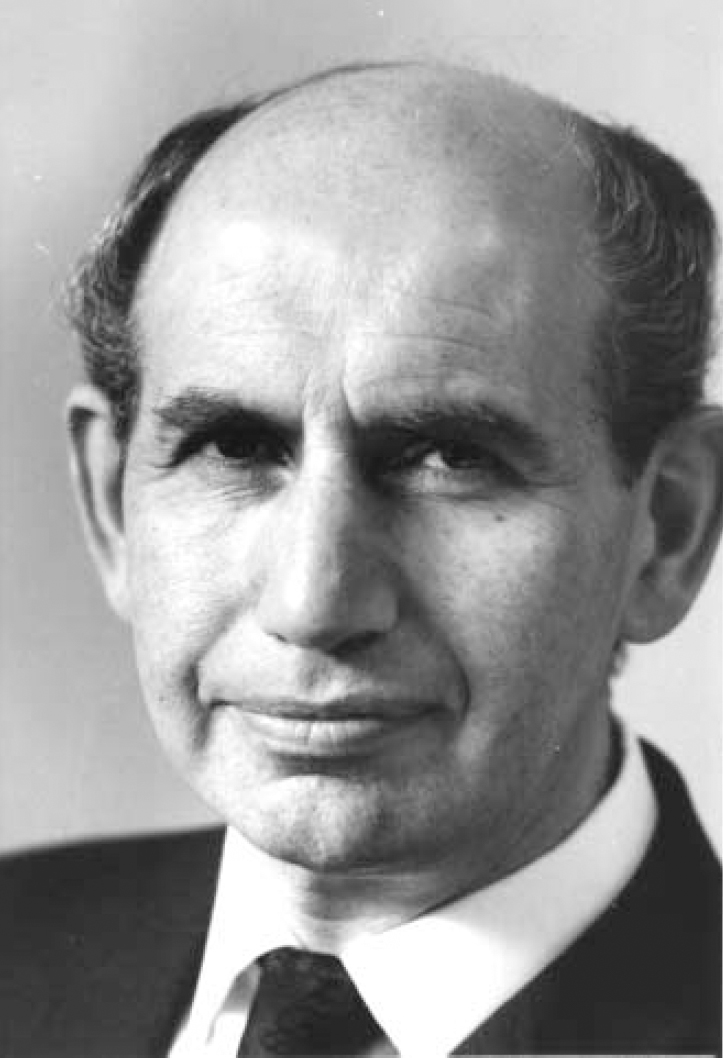

Since the mid-19th century central Europe had been the cradle of conceptual thinking in clinical psychiatry. Following the turbulence and persecution in the 1920s and 1930s some of a later generation of mid-European psychiatrists emigrated to Britain, bringing with them the traditions of meticulous and detailed observation, a broad clinical perspective and fresh ways of looking at problems. Among those individuals making significant contributions were Willy Mayer-Gross, Erich Guttman, Erwin Stengel, Felix Post, F. Kraupl Taylor, Max Hamilton and Martin Roth. Roth, who was born in Budapest in 1917, the last survivor of this extraordinarily gifted group, died on 26 September 2006 at the age of 88.

In this Appreciation, bearing in mind that Martin Roth was not given to talking freely about his own experiences and feelings, we have used some of his own words, spoken on those rare occasions when he revealed more of himself than usual, as he did on the occasion of the celebration on his 80th birthday or when interviewed by one of us (A.K.).

EARLY CAREER

Martin Roth's decision to embark on a career in medicine arose out of ‘the necessity to qualify at something I could make a living at’. He had considered becoming a musician at the age of 13 or 14 but felt he couldn't afford to take the risk. Nevertheless, when a medical student, his talent enabled him to play the organ at weddings and the piano for ballet classes, providing much-needed financial assistance at the time. He continued to play the piano throughout his life, Bach giving him particular pleasure. His entry to St Mary's Hospital in 1936 had been delayed for 3 months by the need for surgery. In 1942 he had to have a much more serious operation. The diagnosis was one of regional ileitis. ‘I expected to have a relatively short life and this [experience] has influenced me very much.’ At St Mary's he had little interest in the prevailing rugby culture, but did row for the hospital.

While a house physician, Roth was struck by the story of Mary Walker, an unassuming physician at a London County Council hospital. Dr Walker had gone to a lecture on myasthenia gravis and had heard that the symptoms bore a close resemblance to curare poisoning. She later asked what the antidote for curare poisoning was, and on being told it was physostigmine gave the drug to some patients with the condition; after an injection, their symptoms vanished. She presented these cases at the Royal Society of Medicine, Martin Roth decided to take a post in neurology at Maida Vale Hospital, where he worked for the outstanding neurologist Russell (later Lord) Brain, who became his friend.

‘but never really gained full recognition for her amazing discovery. But that inspired me. I viewed this as a basis for going into the study of the biological foundations of mental activity.'

‘He [Brain] had a great interest in psychiatry and psychoanalysis which he kept quiet. He was a man of mighty intellect and remarkable gifts as a personality.'

The decision to work in neurology was made in the hope

‘that those activities of the highest level of nervous activity would be presenting disturbances or diseases at the cortical level. The interest of British neurology at the time, with some exceptions, stopped at the neck. Anybody who dabbled above that level was virtually a charlatan.'

After two and a half years Roth became disenchanted with neurology; however, he felt he had learnt a great deal, and commented, ‘I had done my own neuropathology in a case of anosognosia’.

Martin Roth also recalled:

‘I worked in London during the bombing attacks with flying missiles, incendiary bombs and V2 rockets. I took my Membership of the Royal College of Physicians in 1944 when explosions could be heard all around us. Our home near Tower Bridge was bombed and my mother and father moved up to near Manchester. A lot of my possessions were destroyed.'

Having been impressed by the scientific integrity and precision of Eliot Slater's writings, Roth was introduced at his own request to Slater (later to become an influential editor of the British Journal of Psychiatry; Roth was to be a member of this journal's editorial board for 40 years), which proved to be the start of a close, life-long personal and professional relationship. Slater asked him to go to the Maudsley Hospital:

‘When I arrived there I found [Professor Sir Aubrey] Lewis remarkable for his ability to pick out gaps in knowledge and read the relevant literature. At first I was impressed but later I found he poured jars of cold water on people, some of whom gave splendid presentations. I was also finding difficulty with the regime, and I clashed with Lewis. I felt unhappy and it was clear that I had no future there. I left after two years and three months.'

Martin Roth then moved to the Crichton Royal Hospital in Dumfries, a mental hospital with a fine reputation in psychiatric research, where he met Willy Mayer-Gross, whose immense knowledge, enthusiasm and warm-heartedness he found infectious. Mayer-Gross ignited his interest in old age psychiatry by giving him the task of reviewing developments in the field for a chapter in an American book. So began his interest in the clinical area in which his greatest achievements were to be made.

Also while at the Crichton, when only 36, he was invited by Mayer-Gross to become co-author, with Eliot Slater and himself, of what became a highly influential postgraduate textbook in British psychiatry. The first edition of Clinical Psychiatry was published in 1954 and the book was later translated into five languages. Roth himself wrote that it:

‘was intended to foster precise observation and disciplined inference in clinical practice. In research, it recommended an empirical approach [to] the modern classification of psychiatric disorders… The historical and developmental dimension and the concepts of empathy and understanding developed by Jaspers were also treated as essential for the study of neurosis and personality disorder in particular but important for reaching a diagnosis in all forms of disorder.'

This book played a considerable part both in repositioning biological psychiatry at the forefront of clinical practice in the UK and in the dramatic paradigm shift in America in the late 1960s and early 1970s away from the predominance of psychoanalysis and social psychiatry, to give centre stage once more to issues of psychopathology, diagnosis and classification, culminating in the publication of DSM–III. This sudden and remarkable change was described by the eminent American psychiatrist Gerald Klerman in a 70th birthday tribute to Martin Roth as the ‘neo-Kraepelinian revival’, the essential tenet of which was that psychiatry is the specialty of medicine concerned with mental disorders, with the scientific understanding of those disorders and the treatment of individuals suffering from them, utilising a categorical approach. Although this was the approach he espoused, Martin Roth was at pains to emphasise that he did not wish to eliminate dynamic concepts in the study of illness. Those who worked with him clinically were aware of his subtle understanding of the interaction between psychological, social and biological factors in the individual patient.

OLD AGE PSYCHIATRY AND OTHER RESEARCH INTERESTS

After leaving the Crichton Royal, Roth became Director of Clinical Research at Graylingwell Hospital, a large county mental hospital in Sussex, where he carried out his ground-breaking work on the clinical syndromes and outcomes of the mental disorders of old age. In 1958 he was invited by the World Health Organization – the start of a long association with this body – to act as rapporteur and consultant to organise the first Expert Committee on Mental Health of the Aged. This resulted in a working paper that drew attention to the paucity of epidemiological evidence and dearth of research in the whole field.

Roth had moved in 1956, at the age of 39, to take up the Chair of Psychological Medicine in Newcastle upon Tyne. This period, which lasted 21 years, proved enormously fruitful. On arrival, he reorganised the teaching programme and had to answer ward consultations (done in a white coat) because:

‘in an English teaching hospital the professor who does not respond to his consultant colleagues is invisible. He gets no support and I think this is right, so I was often on the wards.'

Indeed, Roth did not shirk the duties of a clinical consultant, with weekly ward rounds, out-patient clinics and case conferences, where he was an inspiring teacher. He established units for child psychiatry, neurosis and psychogeriatrics, and provided postgraduate training for clinical psychologists within his department.

Martin Roth also had to raise research funds and quickly obtained the support of the Medical Research Council, which set up a research group in Newcastle that carried out clinical and outcome studies in affective disorders and epidemiological work in old age psychiatry. The affective work led to a prolonged dispute regarding the classification of depressive illnesses with Robert Kendell, then Reader at the Institute of Psychiatry (and later Professor of Psychiatry in Edinburgh), which remains unresolved to this day. Roth also instigated important clinico-pathological studies with Dr Garry Blessed, consultant psychogeriatrician, and Sir Bernard Tomlinson, then pathologist at the Newcastle General Hospital, which established the pathological distinctness of the clinical syndromes in his classification of old age disorders.

In 1977, at the age of 58, he moved to the Foundation Chair in Psychiatry at Cambridge, where he had to set up a new department but continued his work on affective and anxiety disorders and jointly edited the Handbook of Anxiety, in five volumes (1988–1992). This period was notable also for the publication of CAMDEX, The Cambridge Mental Disorders of the Elderly Examination. However, his most important achievement was to assemble a strong international team, including Claude Wischik and supported by Sir Aaron Klug, to investigate the molecular pathology of Alzheimer's disease.

ROTH AND THE COLLEGE

Another enduring contribution to his specialty was his key role in the establishment of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Although initially he was one of a group of academic psychiatrists who favoured psychiatry becoming a faculty subsumed within the Royal College of Physicians, following a meeting with its President (by a curious quirk of fate, Lord Brain), an abrupt change of course was decided upon and the mainly university group threw in their lot with their colleagues, drawn predominantly from the mental hospitals, who had fought a long and vigorous campaign for an independent Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Although he was a late candidate to stand for the position of first President of the College, Martin Roth was elected by a comfortable margin. Under his leadership psychiatrists in training were given formal involvement and membership on key College bodies, an acknowledgement of the commitment he had given to them at the rumbustious inaugural meeting of the College concerning the need for a truly democratic structure. With Kenneth Rawnsley and William Trethowan he helped establish respectively the model Approval exercise and MRCPsych Examination, with inevitable and substantial benefits to education and training and therefore to clinical standards in psychiatry. However, it was very much Roth's personal achievement during his time in office (1971–1975), acting largely on his own, to find a permanent home for the College. It was from Lord Goodman that he learnt that 17 Belgrave Square was available. The then huge sum of £750 000 had to be borrowed and substantial amounts of interest paid.

‘We didn't choose to go to a fashionable place but we couldn't get any other.'

With additional help from generous sponsors, the premises in one of the most attractive squares in London were secured.

Martin Roth was a dominant personality who possessed charm and wit, an exceptional intellect and breadth and depth of knowledge of the literature within both psychiatry and medicine. He possessed an unusual capacity for addressing conceptual and clinical conundrums in a novel and imaginative way. As Thomas Barnes put it, he could maintain the issue under scrutiny in sharp focus while viewing it from a number of perspectives and within a number of contexts. He was forceful in debate, with his neo-Kraepelinian approach conspicuously at odds with the Meyerian philosophy pervading the Maudsley. Even his extraordinary capacity for work, level of energy and stamina could be put under pressure by his difficulty in saying ‘no’ to a constant series of requests. His command of the English language was supreme, combining readability, a powerful narrative style and organisation, and a fondness for the elegant and esoteric phrase.

To some he was a private, almost Olympian figure, complex and unworldly in small matters, whose awareness of the constraints of time and place could not always be relied upon. Nevertheless, when the occasion arose he displayed warmth, interest, sensitivity and consideration, and he maintained regular contact with his former pupils and colleagues until his final illness. What also lingers is the remarkable empathy he established with patients from a variety of backgrounds, to whom he always showed respect and concern.

Martin Roth was blessed with a loving family and received unfailing support from his wife Constance and their three daughters.

RESEARCH ACHIEVEMENTS

Among Martin Roth's many contributions to scientific knowledge, his work on the mental disorders of later life will be best remembered. His pioneering studies at Graylingwell and Newcastle in the 1950s and 1960s anticipated the surge of dementia research that continues today. However, his early achievement was to show that many elderly patients in mental hospitals, whose illness was attributed to senility and dementia, in fact had treatable conditions such as depression or acute confusion (delirium) and could recover. He specified diagnostic criteria for syndromes of depression and late paraphrenia – ignoring minor intellectual deficits – and was among the first clearly to distinguish acute confusion from dementia. These patients – and geriatric patients in general – performed as a whole much better on cognitive tests than those fulfilling Roth's criteria for senile or arteriosclerotic dementia. The clinico-pathological studies carried out at Newcastle, which extended the work begun by the pathologist J.A.N. Corsellis, demonstrated a quantitative relationship between cognitive level and extent of brain damage, whether of the type found in Alzheimer's disease or arteriosclerotic dementia. These findings placed his separation of dementia proper from functional disorders on a secure basis, led to the birth of the specialty of psychogeriatrics, and transformed the care of the elderly. Subsequently, employing Roth's definitions, a small population-based study, the forerunner of much larger studies in Europe and the USA, allowed preliminary estimates to be made of prevalence, which showed that the rate of dementia increased progressively with age after 60.

Among the functional disorders Roth was fascinated by the non-affective paranoid–hallucinatory psychoses of late onset, found mainly in women, but without evidence of dementia or brain damage, that he called ‘late paraphrenia’. The choice of this term was intended to leave on one side its relation to schizophrenia, but it was open to criticism and the condition now cannot be identified by any rubric in DSM or ICD. This is to be regretted, since its status is still controversial.

At Cambridge he returned to the topic of dementia and his team produced a stream of papers on the molecular pathology of the protein tau, found in an abnormal insoluble form in the Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles – the neocortical density of which is strongly correlated with dementia symptoms – whereas in normal ageing tau remains mostly in solution. Although these studies have not yet led to a specific treatment they constitute a notable scientific achievement.

Martin Roth's studies of affective and anxiety states were undertaken in a climate in which the view of Sir Aubrey Lewis that there was no essential difference between endogenous (or psychotic) and reactive (or neurotic) disorders was predominant. With his colleague Roger Garside, senior lecturer in clinical psychology, Roth used the multivariate statistical programs becoming available on computers to look for categories of illness and distinct patient groups. In a series of papers he found evidence that these groups differed in respect of symptoms, outcome and response to treatment. However, replication by others did not always produce the same results, and the dichotomy implicit between ‘endogenous’ and ‘reactive’ was not always fulfilled. We have looked at the latest editions of the major classificatory systems for an indication of the current status of this dichotomy. In ICD–10 neurotic and stress-related disorders (section F40–48), often with coexistent depression, include phobic-anxiety and other anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and reactions to severe stress and adjustment disorders. The classification of depressive disorders is based on severity, but endogenous (or melancholic) depression finds a place as an option to state whether or not a ‘somatic syndrome’ is present. In DSM–IV the main type of depression is major depressive disorder, but the presence of ‘melancholic features’ – which are identical to those of endogenous depression – can be specified. It appears that although classification has become more complex and nomenclature has changed, the concept of endogenous depression as a distinct non-neurotic disorder survives.

In Aubrey Lewis's classification, depressive and anxiety disorders form a single illness within the affective disorders, distinguished only by severity. Roth showed that after separating cases into anxiety states and depressive illness on the basis of the patients' predominant mood, these groups differed from each other in their clinical features, premorbid personalities, response to treatment and longer-term outcome. The fact that both DSM–IV and ICD–10 allocate affective (mood) disorders and anxiety states to separate sections seems to imply implicit agreement with Roth's view that these disorders are distinct. Both these classifications treat manifestations of anxiety such as panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobias and generalised anxiety as categorical entities, but Roth objected that although this approach had stimulated research, it ignored the traditional European concept of anxiety disorders as manifestations of personality disorder (and therefore as continuous with normality). He concluded that both categorical (syndrome) and dimensional (personality diagnosis) features were necessary to complete the clinical picture of affective disorders, and for prediction of outcome.

For his scientific achievements in psychiatry, particularly in the field of old age psychiatry, Martin Roth became one of only three psychiatrists (of whom the earliest was Sigmund Freud) to be elected Fellow of the Royal Society.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.