Misuse of alcohol, cannabis and other illicit substances is common among people with psychotic illnesses (e.g. Reference Regier, Farmer and RaeRegier et al, 1990; Reference McCreadieMcCreadie, 2002). Recent emphasis has been on the possible causal links between cannabis and psychosis (Reference Arseneault, Cannon and WittonArseneault et al, 2004; Reference Fergusson, Poulton and SmithFergusson et al, 2006) and on the high prevalence of cannabis use among patients with established psychotic disorders (Reference Green, Young and KavanaghGreen et al, 2005); this can complicate treatment and impair recovery. However, other substances are also frequently misused by people with psychotic disorders with similar ramifications. Our primary aim was to describe lifetime and current substance use in an epidemiologically representative sample of people experiencing a first episode of clinically relevant psychosis in Cambridge and south Cambridgeshire between June 2002 and June 2005. Secondary aims included determining the extent to which our sample represented the true incidence of psychosis in the area and investigating associations between illness duration and substance use.

METHOD

Setting

Cameo is a specialist early intervention service for people in Cambridge and south Cambridgeshire who experience a first episode of psychosis. Referrals are accepted from multiple sources including general practitioners, mental health services, school and college counsellors, relatives, and self-referrals. People referred to the service received a comprehensive clinical assessment, including assessment of the history of psychotic symptoms and of lifetime and current substance misuse.

Sample

The sample comprised consecutive referrals to the Cameo service between June 2002 and June 2005. Inclusion criteria were the presence of positive or negative symptoms for the first time, or previous episodes that had been untreated, or were treated for less than 6 months with antipsychotic medication. DSM–IV diagnoses were established using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID; Reference First, Spitzer and GibbonFirst et al, 1997). People with drug-induced psychoses and affective psychoses were included; those with intellectual disability were excluded.

Inclusion criteria were altered during the study period as the Cameo service developed according to National Health Service guidance (Department of Health, 2001) and local implementation. The age range was initially 17–65 years but changed in April 2004 to 17–35 years. The catchment area comprised Cambridge City and South Cambridgeshire Primary Care Trust; the east Cambridgeshire area was included only up to November 2004. Incidence calculations took into account these demographic and geographical changes when determining the population-at-risk.

Assessments

Demographic information and the history of psychotic symptoms were ascertained at the initial clinical interview. A second interview was then conducted within 2 weeks of referral to the service, subject to the patient being well enough to complete further assessments at this time. At this second assessment, the SCID interview (Reference First, Spitzer and GibbonFirst et al, 1997) was completed by a researcher trained in its use, and substance use assessed using the St George's Substance Abuse Assessment Questionnaire (Reference GhodseGhodse, 2002). Patients indicated if they had ever used any of the following: alcohol, cannabis, solvents, heroin, methadone, crack/cocaine, ecstasy, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, amphetamines, hallucinogens, or ketamine. Patients were asked the age at which they had first used each substance and the frequency of substance use over the past 30 days. Any features of dependence were identified. Lifetime substance use was classified according to DSM–IV criteria into no use, use, and abuse or dependence.

Four measures of illness duration were extracted from patient and carer reports and case notes, where available. These were chosen to cover a range of the possible conceptions of illness duration (Reference Norman and MallaNorman & Malla, 2001). Where reports from different sources conflicted, the longer duration was taken. The four measures were as follows: (a) Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) for the index episode: the time in months that psychotic symptoms were present without remittance before treatment was initiated for the index episode; (b) duration of untreated illness for the index episode: the time in months before treatment that some discernible change in behaviour or well-being had been present without remittance for the index episode; (c) age at first ever psychotic symptom: the age at which the first-ever psychotic symptom was experienced according to patient report; (d) lifetime duration of psychosis: the age at the time of assessment minus the age at first psychotic symptom. This represented an approximate measure of the lifetime duration of psychotic experiences.

The majority of patients assessed in the Cameo service during this period underwent a cognitive assessment (see Reference Barnett, Sahakian and WernersBarnett et al, 2005). Premorbid IQ was estimated for patients who were native English speakers (n=90) using the National Adult Reading Test (NART; Reference NelsonNelson, 1982).

Participants gave informed consent to be interviewed and the procedure for using routinely gathered clinical information to generate aggregate research reports was approved by the Cambridge Local Research Ethics Committee.

Expected psychosis incidence

We estimated the extent to which our sample represented the expected number of incident cases of clinically relevant psychoses by reference to published data and knowledge of our population-at-risk. The age- and gender-specified incidence of all psychoses from the Nottingham centre of the ÆSOP study (Reference Kirkbride, Fearon and MorganKirkbride et al, 2006) were used as the basis to predict the incidence of first-episode psychosis in the population served by Cameo. The Nottingham incidence rates by gender and 5-year age band were applied to similarly stratified estimates of our population-at-risk ascertained from the 2001 UK census (Office for National Statistics, 2003). This generated an expected number of incident psychosis cases adjusted for age and gender, with which we compared our observed number of cases over the period of the survey. Changes in age range and catchment area as the service evolved were taken into account; numbers of expected cases for the periods June 2002 to April 2004, April 2004 to November 2004 and November 2004 to June 2005 were calculated separately and summed for the total study period.

Drug use prevalence

The 2002–03 British Crime Survey (Reference Condon and SmithCondon & Smith, 2003) was used as a basis for comparison of substance use in people with first-episode psychosis and the general population. This is a large national survey of adults living in a representative cross-section of households in England and Wales. Since 1996, the survey has included questions on drug use and reports the prevalence of substance use for those aged 16–59 years. Since drug use varies considerably with age, age-adjusted general population estimates were produced by multiplying the prevalence in the British Crime Survey by the proportion of Cameo patients falling within the survey's published age ranges (16–24, 25–34 and 35–59 years). Under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 the following substances are classified as Class A drugs: opiates, cocaine, hallucinogens and ecstasy. The British Crime Survey distinguishes between other substances and Class A drugs; we followed the same distinction in our sample. Enhanced data are available within the British Crime Survey for substance use (excluding alcohol) among 16- to 24-year-olds. This age group was considered separately in our study to take advantage of this and because of the increased risk for onset of psychosis within this age group.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of the proportion of men and women who had used each substance were made by calculating odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Measures of illness duration deviated from the normal distribution according to the one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Associations between NART-estimated IQ, measures of illness duration and age at first use of each drug were therefore made using Spearman's rho. Mann–Whitney U-tests were used to compare men and women for the age at first use of each substance.

RESULTS

Sample completeness

The denominator population over the study period included 470 246 person-years. Age- and gender-adjusted incidence rates from the ÆSOP study predicted 134.0 cases of first-episode psychosis in the population served by Cameo over the period June 2002 to June 2005. During this period, 139 people with first-episode psychosis were assessed by the service. In addition, 8 people were later identified who met the criteria during this period but were not referred to the service. It is therefore likely that Cameo assessed the vast majority of incident cases of clinically relevant psychosis, perhaps between 90 and 95% of all those arising within the catchment area.

Sample characteristics

Data on substance use were available from 123 of the 139 people with first-episode psychosis referred to Cameo during this period (88%). The remainder (n=16) declined to participate in the assessment at which substance use was reported. Of those who did complete the assessments, 93 (75.6%) were men, with a median age of 25 years (range 17–65). Mean NART-estimated premorbid IQ was 110.0 (s.d.=8.3, range 92–124). Of patients who underwent the SCID interview, only 1 received an initial diagnosis of drug-induced psychotic disorder. The most common initial diagnoses were schizophrenia and schizophreniform psychoses (n=35); mood disorders (n=37) and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (n=37), including cases where it was unclear whether the psychosis was drug-induced.

Lifetime substance use

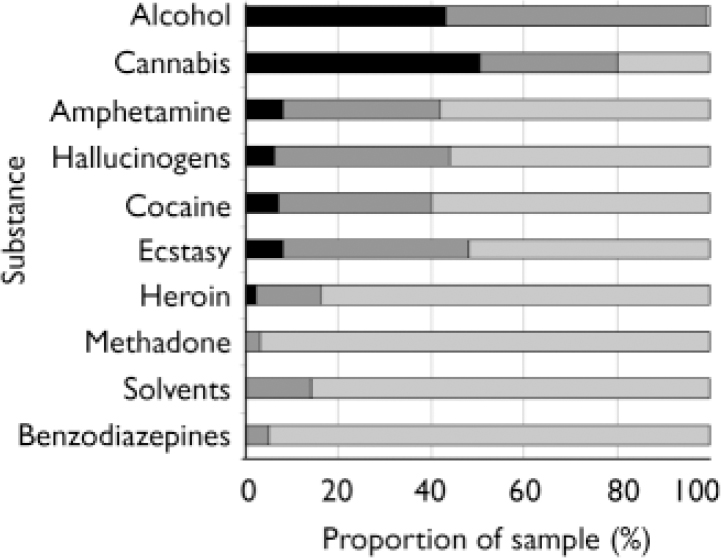

Lifetime substance use of the sample is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. In some cases participants did not disclose their use, or otherwise, of every substance; for this reason sample sizes vary between substances.

Table 1 Correlation between age at first substance use and age at onset of illness in first-episode psychosis.

| Age at first use of substance | Spearman's rho | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first psychotic symptom | DUP this episode | DUI this episode | Lifetime duration of psychosis | |

| Alcohol (n=63) | 0.05 | 0.04 | -0.07 | 0.07 |

| Cannabis (n=64) | 0.38** | -0.03 | -0.04 | -0.05 |

| Cocaine (n=29) | 0.62** | 0.01 | -0.15 | -0.12 |

| Ecstasy (n=34) | 0.53** | -0.24 | -0.12 | -0.16 |

| Amphetamine (n=28) | 0.60** | -0.59** | -0.19 | -0.24 |

| Hallucinogens (n=29) | 0.23 | -0.41* | -0.38* | 0.01 |

Alcohol

Alcohol use was almost universal: only 1 participants out of 123 reported never having consumed alcohol. Nearly half the sample (n=53, 43.1%) met DSM–IV criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence at some point in their life, with the remainder (n=69, 56.1%) reporting alcohol use but not abuse. Median age at first use was 15 years (range 5–30 years).

Cannabis

Cannabis was the next most commonly used substance. Of 122 participants, 98 (80.3%) reported using cannabis at some time in their life. More than half (n=62, 50.8%) met DSM–IV criteria for cannabis abuse or dependence. Age at first use of cannabis ranged from 7 to 30 years (median 15 years).

Class A drugs

Class A drug use was common, and included use of ecstasy (n=57), hallucinogens (n=52), crack or cocaine (n=49) and heroin (n=20). Methadone use was uncommon (n=4).

Other substance use

Amphetamine use was common (n=49). Rarely used substances included solvents (n=16), ketamine (n=7) and benzodiazepines (n=6). There were no reports of barbiturate use.

Substances used by fewer than 20 patients were not subjected to subsequent analyses because of power limitations.

Gender differences

Men with first-episode psychosis were slightly more likely than women to have used heroin (OR=1.3, 95% CI 1.2–1.4), and three times more likely to have used ecstasy (OR=3.4, 95% CI 1.4–8.4) or hallucinogens (OR=3.4, 95% CI 1.3–8.6) during their life. There was also a trend towards more cocaine use in men (OR=2.3, 95% CI 0.9–5.5). Men and women did not differ in amphetamine or cannabis use. Comparisons of usage between men and women were not possible for solvents, ketamine, benzodiazepines and methadone because of the small number of patients (n<20) who had used these substances.

Fig. 1 Lifetime alcohol and substance use in first-episode psychosis (n=118–123) according to DSM–IV diagnosis. ▪, abuse or dependence; ![]() , use but not abuse;

, use but not abuse; ![]() , never used.

, never used.

There were no significant differences between men and women in the age at first use of any substances. There was a trend towards earlier first use of cannabis in men (mean 15.6 years) than women (mean 17.9 years; z=–1.90, P=0.06).

Estimated premorbid IQ

NART-estimated IQ was not associated with any of the measures of duration of illness or with age at first use of any substance. Groups defined by the use or non-use of each substance did not differ in their NART-estimated IQ.

Polysubstance abuse

A high proportion of participants met DSM–IV criteria for lifetime abuse or dependence for more than one substance (Fig. 2).

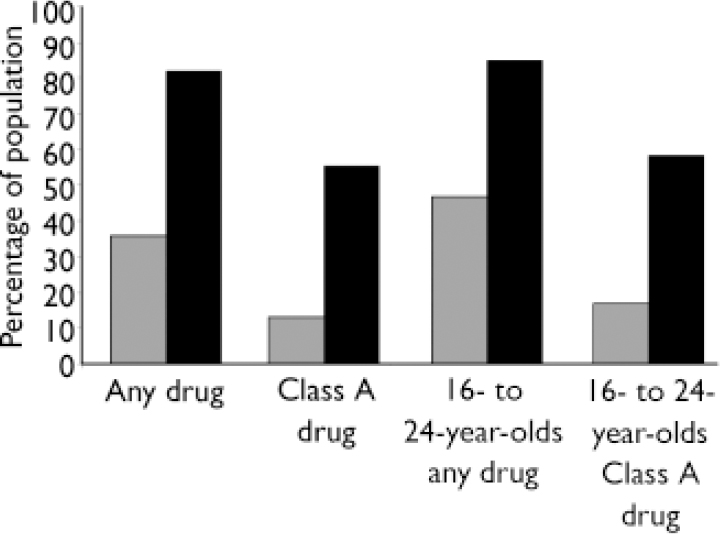

Comparison with general population

Lifetime prevalence of substance use in our group with first-episode psychosis was considerably greater than national estimates from the British Crime Survey (Fig. 3). Most notably, more than half of our patients (n=68, 55.3%) had used one or more Class A drug, compared with 13% of the general population.

Fig. 2 Venn diagram of lifetime substance abuse/dependence in 119 people with first-episode psychosis in the CAMEO service.

Fig. 3 Lifetime substance use in first-episode psychosis in the Cameo service and in the general population of England and Wales (British Crime Survey 2002–03, not adjusted for age). ![]() , General population; ▪, Cameo.

, General population; ▪, Cameo.

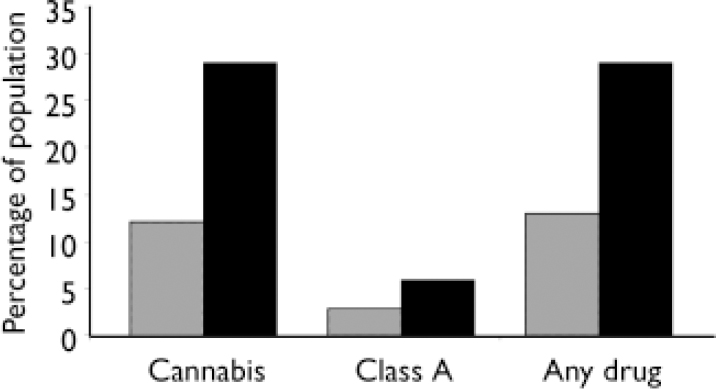

Fig. 4 Substance use in the past 30 days in people with first-episode psychosis and the general population (British Crime Survey 2002–03, adjusted for age distribution). ![]() , General population; ▪, Cameo.

, General population; ▪, Cameo.

Additional comparisons were made in the 16- to 24-year age group. Of 60 people within this group, 85% (n=51) had used at least one drug, compared with a national estimate of 47%. Lifetime prevalence of cannabis use among our participants was 83% and Class A drug use was especially common: 58% compared with a national prevalence of 17%.

Substance use in previous 30 days

Of our participants with first-episode psychosis, 29% reported using one or more substances (other than alcohol) within the previous 30 days compared with 13% of the general population (age-adjusted prevalence; see Fig. 4). Almost all of the substance use in the preceding month was accounted for by cannabis: 29% of patients compared with 12% of the general population (age-adjusted prevalence). Seven patients (5.9%) had used Class A drugs within the past month (age-adjusted national prevalence 2.8%) and an additional 2 patients (1.8%) had used amphetamines during this period (age-adjusted national prevalence 1.1%).

Duration of illness and age at first substance use

Spearman's correlations were used to determine the association between duration of illness and age at first use of substance, for those substances for which data were available for at least 20 participants (Table 1). Age at first psychotic symptom was positively associated with age at first use of cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy and amphetamines, but not alcohol or hallucinogens. There were negative associations between duration of untreated psychosis for this episode and age at first use of amphetamines and hallucinogens, and between hallucinogen use and duration of illness for this episode. This suggests that patients who start taking drugs at a younger age take longer to seek treatment after experiencing their first psychotic symptom. No associations were found between lifetime duration of untreated psychosis and age at first drug use.

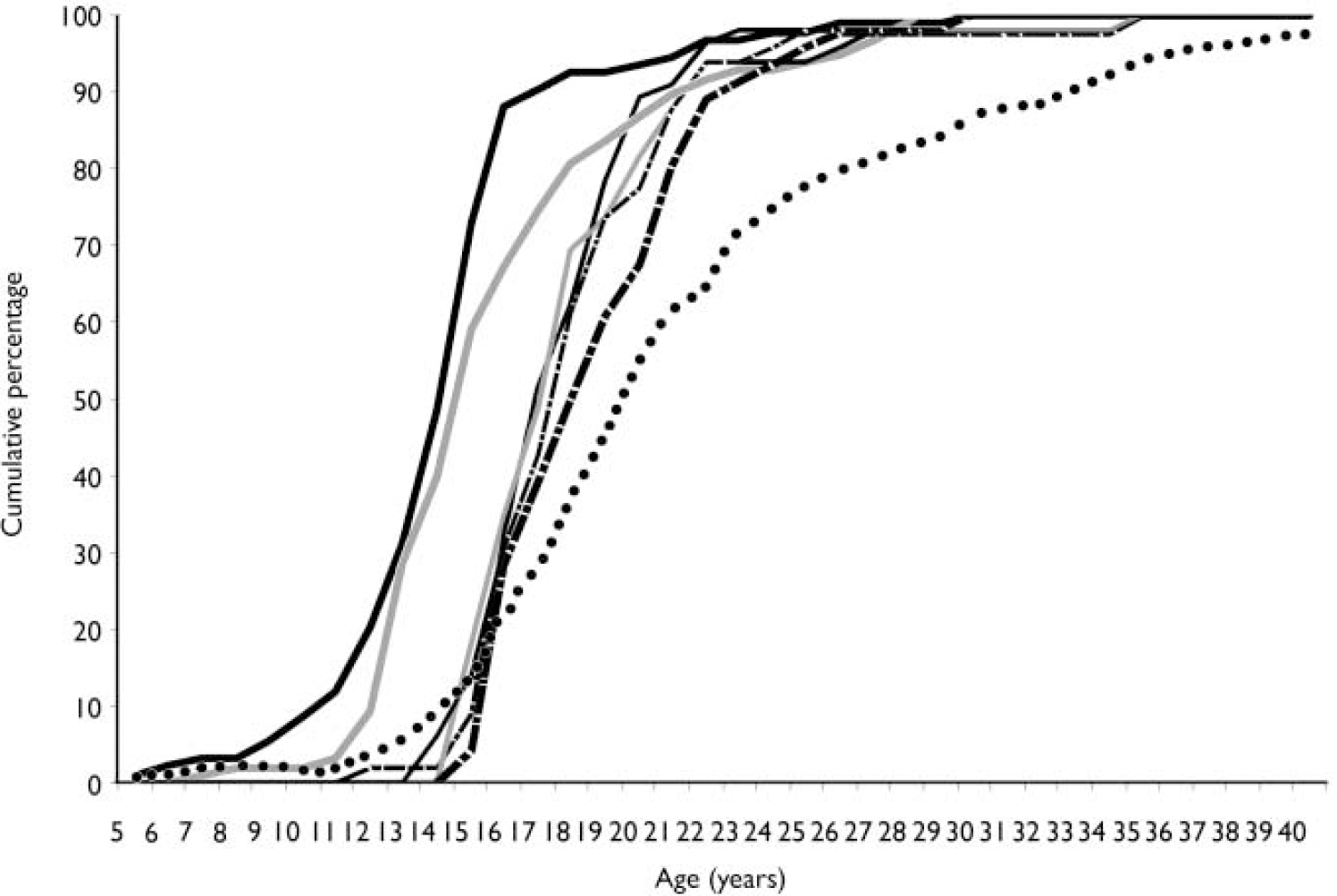

The age at which patients first used each substance is shown in Fig. 5. For alcohol and cannabis, the peak age for first use was between 12 and 14 years, whereas for ecstasy, amphetamines, hallucinogens and, to a lesser extent, cocaine, the peak age for first use was between 14 and 19 years. In the majority of patients referred to the Cameo service, first substance use was several years prior to the first psychotic symptom.

Fig. 5 Age at first use of each substance and at first psychotic symptom among study participants. Included are all people with first-episode psychosis where both age at first substance use and age at illness onset are known. ![]() , Alcohol(n=93);

, Alcohol(n=93); ![]() , cannabis (n=98);

, cannabis (n=98); ![]() , cocaine (n=46);

, cocaine (n=46); ![]() , ecstasy (n=56);

, ecstasy (n=56); ![]() , amphetamine (n=49);

, amphetamine (n=49); ![]() , hallucinogen (n=49);

, hallucinogen (n=49); ![]() , first psychotic symptom (n=88).

, first psychotic symptom (n=88).

DISCUSSION

Prevalence of substance use

The overall prevalence of substance use in people with first-episode psychosis was approximately double that in the general population of similar age. There were few participants in our study who had not used illegal drugs; more than half met DSM–IV criteria for lifetime substance abuse or substance dependence and more than a third had lifetime diagnoses of polysubstance abuse.

The high prevalence of substance use among people with first-episode psychosis is in accordance with previously published data from the UK (Reference Cantwell, Brewin and GlazebrookCantwell et al, 1999), North America (Reference Van Mastrigt, Addington and AddingtonVan Mastrigt et al, 2004) and Australia (Reference Wade, Harrigan and EdwardsWade et al, 2006). A recent review (Reference Green, Young and KavanaghGreen et al, 2005) based on 53 treatment samples found prevalence estimates of cannabis use of 42% for lifetime use (Cameo prevalence 80%) and 23% for current use (Cameo prevalence 29%).

The high prevalence of substance use in our participants with first-episode psychosis is particularly notable given that we estimate that the sample is representative of all people who experience a clinically relevant first psychotic illness. This is interesting with respect to the general pattern where population-based samples produce lower estimates of substance use than samples recruited from clinics (Reference Green, Young and KavanaghGreen et al, 2005). However it should be noted that substance use data were not available for the entire sample, and that we did not include people with psychotic symptoms or syndromes who did not present to services, or a small number of people with first-episode psychosis that were not referred to the service.

The increased prevalence of substance misuse in first-episode psychosis relative to the general population may even have been underestimated in this study. Underdetection of substance use among psychiatric patients is widespread: a UK study found that substance use among acute admissions could be detected by urinalysis twice as often as was mentioned in medical or nursing notes (Reference Ley, Jeffery and RuizLey et al, 2002). A second study compared the extent of substance use as reported by patients with schizophrenia, co-informants such as a relative or keyworker, and by hair and urinalysis (Reference McPhillips, Kelly and BarnesMcPhillips et al, 1997) and found severe underreporting by patients for cocaine and amphetamines, although self-report of cannabis use was both more frequent and more accurate, as judged by informant report and urinalysis.

People with first-episode psychosis might be wary of admitting to excessive substance use in case it affects their clinical management, diagnosis, or simply because it might elicit a judgemental response from staff. In addition, estimates of drug use in the past month may be reduced in current in-patients referred to the Cameo service relative to their normal levels of drug use, although we note that drug use among inpatients is a growing problem.

Substance use in first-episode psychosis might be expected to be more common than in the general population since the sample includes an excess of young, single men; factors associated with increased substance use (Reference Chivite–Matthews, Richardson and O'SheaChivite-Matthews et al, 2005). South Cambridgeshire is relatively affluent but has a disproportionate number of young adults (Office for National Statistics, 2003). Although the ÆSOP and British Crime Survey data are the best available for comparison, the Cameo catchment area clearly differs from the Nottingham and national samples in some ways (for example, in ethnicity and urbanicity). None the less, it seems unlikely that the demography of the catchment area would explain the high levels of substance use in our sample.

Significance of substance use

The high prevalence of substance use reported in this sample of people with first-episode psychosis has important clinical implications. Substance misuse in people with psychotic disorders is robustly associated with non-adherence to treatment (Reference Weiiss, Smiith and HullWeiss et al, 2002; Reference Nose, Barbui and TansellaNose et al, 2003; Reference Margolese, Malchy and NegreteMargolese et al, 2004) and poorer outcomes (Reference Verdoux, Tournier and CougnardVerdoux et al, 2005), whereas a reduction in substance use after diagnosis is associated with a reduction in subsequent admissions and psychotic symptoms (Reference Sorbara, Liraud and AssensSorbara et al, 2003; Reference Lambert, Conus and LubmanLambert et al, 2005). Follow-up (15 months) from a similar service for first-episode psychosis suggests that around three-quarters of patients with a lifetime diagnosis of substance misuse will continue to misuse after the initiation of treatment (Reference Wade, Harrigan and EdwardsWade et al, 2006).

Identification and reduction of substance use and misuse should be a key therapeutic target for early intervention services and has implications for staff training. Management of cannabis misuse is not a focus of specialist substance misuse services and dual-diagnosis services tend to focus on chronic, not first-episode patients. This study suggests that dual-diagnosis services should become part of early intervention efforts. However, the current evidence base is scant; further treatment trials and the development of therapeutic strategies are clearly required.

There were associations between age at onset of psychosis and age at first substance use. A previous study found that cannabis use was predictive of earlier onset of schizophrenia (Reference Veen, Selten and van der TweelVeen et al, 2004) and a second study showed that early use of cannabis (prior to 16 years) was associated with both positive and negative dimensions of psychosis (Reference Stefanis, Delespaul and HenquetStefanis et al, 2004). Buhler et al (Reference Buhler, Hambrecht and Loffler2002) attempted to clarify the precedence of heavy substance use, the onset of any schizophrenia symptoms (including negative symptoms) and the onset of psychotic symptoms. They found that first drug misuse and the onset of general symptoms tended to coincide, but there was no correlation between first drug misuse and the onset of psychotic symptoms. As in that study, our findings were partly confounded by the age of the participants (i.e. it was not possible to assess the association in those who were already psychotic but will in the future start using illicit substances). None the less, they do provide further evidence for an association between early substance use and onset of psychosis. From the public health standpoint, it seems clear that preventative measures regarding drug use need to be targeted at children in the preteenage years; our data suggest that the transition from junior to senior schools might be an important juncture

In the general population, people who smoke cannabis are more likely to become psychotic (Reference Andreasson, Allebeck and EngstromAndreasson et al, 1987; Reference Zammit, Allebeck and AndreassonZammit et al, 2002). Early use may be particularly potent (Reference Arseneault, Cannon and PoultonArseneault et al, 2002), which is consistent with our findings. However, there are a number of possible explanations for the association, including models where a common factor explains both substance use and psychosis, models where substance use is secondary to psychosis or where psychosis is secondary to substance use, and, theoretically, bi-directional models where psychosis and substance use interact in their causation and maintenance (Reference Mueser, Drake and WallachMueser et al, 1998; Reference Fergusson, Poulton and SmithFergusson et al, 2006). The associations between age at first substance use and age at first psychotic symptoms might be explained by any or all of these hypotheses; our data do not distinguish these alternatives.

An important implication of our results is that the prevalence of the use of substances other than cannabis is high and might be equally important. Recent debates regarding the legal status and safety of cannabis might have diverted attention from the importance of other substance misuse. The prevalence of cannabis use was, indeed, higher in people with first-episode psychosis than in the general population. However, the prevalence of other substance misuse, notably Class A drugs and, at the other end of the legal spectrum, alcohol was greater still. Although age at first cannabis use was significantly associated with age at onset of psychosis, associations between age at first use of cocaine, ecstasy, and amphetamines were even stronger. The high levels of polysubstance misuse and misuse of substances with a high potential for addiction are clinically and socially important, and should be the subject of further research. We did not assess the use of nicotine which might be linked with progression to other drugs, has serious health consequences itself and might even be linked to the underlying biology of psychosis.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Cameo service and the ÆSOP study team. The Cameo service received pump priming funding from the Stanley Medical Research Institute and GlaxoSmith Kline, and now receives support from the National Health Service. J.H.B. and P.B.J. were funded by the Medical Research Council and the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.