Introduction

According to the United Nation Refugee Agency, 65.5 million people around the world have been forced to flee from their home country (McBrien, Reference McBrien2017), including 22.5 million refugees. More than half of these individuals are from three countries: South Sudan, Afghanistan and Syria. These individuals encounter a variety of hardships during their displacement before arriving at their final destination. There have been many efforts to assist the integration process of refugees who have come to Western European countries and the United States, so that these individuals might be connected with therapeutic resources such as individual psychotherapy, group psychotherapy, community-based interventions, or psychoeducational programmes based on community resources or needs (Suárez-Orozco et al., Reference Suárez-Orozco, Motti-Stefanidi, Marks and Katsiaficas2018). It is common for individuals seeking asylum to be referred for psychological and medical evaluations by the immigration agencies or lawyers working on their behalf. Access to psychological interventions or assessment differs based on the availability of resources and asylum-seeking requirements in the host country.

At the time of writing, members of gender and sexual minority (GSM) communities have been persecuted, punished, and executed in many countries with a Muslim majority. There are three Islamic countries that are known to punish homosexual relationships between men with death: Iran, Saudi Arabia and Sudan (Carroll and Itaborahy, Reference Carroll and Itaborahy2015). There are also countries with no official policy of punishment, such as Turkey and Jordan, where persecution still occurs (Kıraç, Reference Kıraç2016). Moreover, even in Muslim majority countries without formal legal punishments, many individuals who belong to the GSM population have been the target of honour killing by close family members (Carroll and Itaborahy, Reference Carroll and Itaborahy2015; Terman, Reference Terman2014). Such structural sources of stigma have been associated in international research with high rates of self-concealment, in order to mitigate exposure to more direct forms of bias (Pachankis and Bränström, Reference Pachankis and Bränström2018). Identifying as a part of the GSM community might motivates some to seek asylum elsewhere, although others might choose to pursue this option only after living far from home and discovering a deeper sense of safety in a more socially accepting environment. Providers of psychological services to Muslim GSM populations are required to have in-depth understanding of both internal and external factors that affect their clients.

In contemporary psychotherapeutic responses to GSM clients, Islamic communities have often approached well-worn paths created by Christian conservatives in the USA and Europe. For instance, within many Muslim majority countries or communities it is common to refer those struggling with sexual orientation to seek therapy with the intent of returning an individual to a hypothesized ‘heterosexual’ self. Many of these authors’ clients have participated in such therapies, and in some cases, a desire to seek therapists more skilled in sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE) led to the client’s initial move to the USA or Europe. Research on SOCE shows it to be largely ineffective, however (e.g. American Psychological Association, 2009). There has been some indication that exposure to SOCE may increase suicidality (Schroeder and Shidlo, Reference Schroeder and Shidlo2001), although one common positive experience is that, for the first time, men who experience no attraction to women have found that there are other men like themselves who deeply value their faith (Schroeder and Shidlo, Reference Schroeder and Shidlo2001). Similarly, some religious leaders have encouraged individuals who only experience same-sex attractions to live celibate lives. There is a dearth of research on this phenomenon, although research within Mormon communities suggests that when a gay or lesbian person lives a celibate life for faith-based reasons, the negative impact affects both the individual and their families (Dehlin et al., Reference Dehlin, Galliher, Bradshaw and Crowell2015, Jaspal, Reference Jaspal2014).

The aim of this paper is to provide a case conceptualization framework that integrates the use of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson2012; Skinta and Curtin, Reference Skinta and Curtin2016), which corresponds to a number of traditional Muslim practices, with compassion-focused therapy (CFT; Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010). The vignette following describes a composite client representing common issues encountered by the authors and an example of how a culturally competent acceptance and compassion-based approach might function in practice.

First, the important principles of cultural adaptation, minority stress, and the role of shame in relation to Muslim diaspora clients, are reviewed to provide context for why ACT may be a good fit for providing culturally sensitive psychotherapy to GSM Muslim diaspora clients.

Cultural adaptations and contextual behaviour therapy

Although behaviour therapy is not the most frequent approach described when considering culturally responsive interventions, extensive attention has been paid in recent years to what it might look like to incorporate cultural factors into case formulation and treatment planning with minority group members (e.g. Masuda, Reference Masuda2014; Skinta and Curtin, Reference Skinta and Curtin2016). Cultural adaptation in contextual behaviour therapy emphasizes the importance of obtaining culture-specific information that can inform a functional analysis, such that an individual’s history is always viewed through the lens of being grounded in a particular social history (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Muto and Masuda2011). Furthermore, culture-specific adaptations of evidence-based therapies sensitive to the social context of people of colour have led to well-documented improvements in outcome (e.g. Smith et al., Reference Smith, Rodríguez and Bernal2011). In the case of Muslim GSM clients, this means that a culturally competent clinician is informed and knowledgeable about not only GSM communities, but also Islamaphobia in Western cultures and the common factors associated with refugee and asylum seeking status and immigration. The intersectional nature of Muslim GSM individual experiences requires additional knowledge of the specific experiences that occur within those identities in GSM spaces: sexual racism, racism and Islamaphobia. With this emphasis in mind, consider that each aspect of minority stress and shame described below may be experienced in idiosyncratic ways that are not generalizable from either GSM or Muslim populations separately. Cultural information should be considered a source of hypothesis generation, balanced by a careful behavioural analysis of the individual client with whom you are working (Hayes and Toarmino, Reference Hayes and Toarmino1995).

Minority stress theory

Meyer’s minority stress theory is the primary research lens used to understand the challenges that sexual minorities experience (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Meyer, Reference Meyer2003). Minority stress theory describes how the minorities’ experience of societal stigma manifests through self-stigma (e.g. internalized homophobia, internalized biphobia, and internalized transphobia), expectation of rejection, the stress of concealment, and discriminatory or prejudicial actions. The source of the conflict can be located between the lived-experience of belonging to a minority group while subjected to the disparaging norms of a dominant culture (Meyer, Reference Meyer1995). In the context of GSM individuals in Islamic culture, there are a great deal of external and internal sources of stigma that may lead to high level of distress. Minority stress theory suggests how the variety of health disparities in GSM populations is related to their experience of living in a hostile, biased culture that does not allow one to freely explore GSM aspects of the self. This often leads to a lifetime of harassment, maltreatment, discrimination and victimization in these individuals, which may influence the person’s access to services (Marshal et al., Reference Marshal, Friedman, Stall, Kling, Miles, Gold and Morse2008; Meyer, Reference Meyer2003)

Shame

From an evolutionary perspective, emotions are a legacy that insure our survival, allowing us to adapt to the changing environment and survive impending threats to our physical well-being (Levenson, Reference Levenson2014). The universality of certain basic human emotions (i.e. happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, disgust) has received some support in cross-cultural research (Ekman, Reference Ekman1973). Findings are more contradictory, however, when extending the scope of study from the universality of emotional experience to the specific, contingent ways in which emotions are expressed across cultures (Hess and Thibault, Reference Hess and Thibault2009; Mesquita et al., Reference Mesquita, Barrett and Smith2010). Any behavioural account of an emotion, such as shame, requires attending to the functional aspects of the emotion within a specific context. In this case, most nations with Muslim majorities are classified as shame-based cultures (e.g. Fattah and Fierke, Reference Fattah and Fierke2009). In North America and Northern European countries (guilt-based cultures), where many psychological interventions have been developed, guilt regarding one’s actions and the expiation of guilt through conciliatory acts are the primary means of social control. In shame-based cultures, flaws represent failures of one’s moral character, requiring defence against humiliation.

Although shame is not a unique experience associated with any specific diagnostic label, it has been linked to depression (Orth et al., Reference Orth, Berking and Burkhardt2006; Thompson and Berenbaum, Reference Thompson and Berenbaum2006), post-traumatic stress disorder (Leskela et al., Reference Leskela, Dieperink and Thuras2002; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Drozdek and Turkovic2006), substance abuse (Dearing et al., Reference Dearing, Stuewig and Tangney2005), and suicide (Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Northman, Tangney, Joiner and Rudd2000; Lester, Reference Lester1998). The specific impact of shame on GSM individuals likely varies by identity, as past research has suggested specific patterns of substance use or psychiatric disorder across gay, bisexual, lesbian and transgender individuals (Cochran and Mays, Reference Cochran and Mays2009). Shame plays a significant part in addictive behaviours and substance use disorders among GSM individuals (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Lorah and Fenton2006). These behaviours may be used as an attempt to escape or soften difficult feelings, and the very behaviours engaged in to alleviate painful emotions may become another source of shame in the cycle, as in the case of compulsive sex among sexual minority men (e.g. Quadland and Shattls, Reference Quadland and Shattls1987).

A model case formulation for Muslim GSM clients

There are unique features of both the clinical presentation and sources of shame experienced by GSM-identified clients from the Islamic diaspora seeking services in Europe, North America, and Australia. Some Muslim GSM clients seeking therapy have experienced persecution or violence regarding their sexual orientation or gender presentation in their nation of origin and relocated through an asylum or refugee programme (Rodriguez, Reference Rodriguez2017). In these cases, there may be shame over one’s sexuality, or the shame of the sex role violation of having been a victim of violent crime and unable to defend one’s self (Herek et al., Reference Herek, Gillis and Cogan1999).

It is also not uncommon that therapeutic services themselves are sources of distress or internalized stigma (Austin et al., Reference Austin, Craig and D’Souza2018). Many have explored or experienced psychotherapy in a Western nation, such as the United Kingdom, or in a Muslim majority country of origin, with the goal of changing their sexual orientation or attempting to remain celibate as one means of masking their sexuality. When these efforts are unsuccessful, as is generally the case, there may be shame associated either with treatment failure, the process of therapy, or the internalization of views that same-sex attractions are due to some form of psychopathology. While the literature is incomplete and does not allow for a perfect comparison, faith-based psychotherapy in North America and Europe (e.g. evangelical or fundamentalist Christian informed psychotherapies) have followed a similar course over recent decades of encouraging change of one’s sexual orientation or voluntary celibacy, and only more recently acknowledging the centrality of loving, intimate relationships in the lives of individuals (e.g. Marin, Reference Marin2009). This has even led some Christian psychotherapists to encourage the advocacy of greater flexibility within their faith organizations for those in same-sex marriages who are attempting principled lives according to rules of their religion (Bozard and Sanders, Reference Bozard and Sanders2011). Approaches to work with GSM clients within Islam-informed psychotherapy are still unfolding.

In addition to those more general experiences, there are often stressors that occur within GSM communities that are not often accounted for by heterosexual providers (Bowman and Madsen, Reference Bowman and Madsen2018). For instance, sexual racism refers to the ways in which sexual stereotypes may serve to either marginalize or fetishize men of colour, and there is a long history of the fetishization of Arab men within Europe and North America (e.g. Massad, Reference Massad2008). Further, shaming or pressure may be applied by new friends or romantic partners urging gay or bisexual Muslim men to express affection publically, engage in sexual non-monogamy, or other behaviours that are common in visible, urban gay communities, and uncommon and dangerous within most Islamic nations.

Finally, some sources of shame that are common yet not universal relate to the process of asylum. With the globalization of many jobs and educational opportunities, some men are able to justify relocation from one’s country of origin to their families and to avoid explaining that they have sought asylum for many years. This magnification of secrets between an individual and his family can feel shameful or challenging, particularly if this is in addition to not disclosing one’s sexuality to one’s family. This also creates a context in which shaming interactions are more likely to occur. For instance, one of the authors worked with a client who hid his application for asylum from his family. Until he eventually disclosed this, he was subject to increasingly frequent pleas by his parents to visit the family home in his country of origin, which is prohibited during, and in many cases, after successful bids for asylee status to the United States – if one is truly in danger for one’s sexuality, how can one safely travel home? This creates a conundrum for individuals who do not wish to come out to their families, yet wish to live openly and seek romantic relationships in their new home.

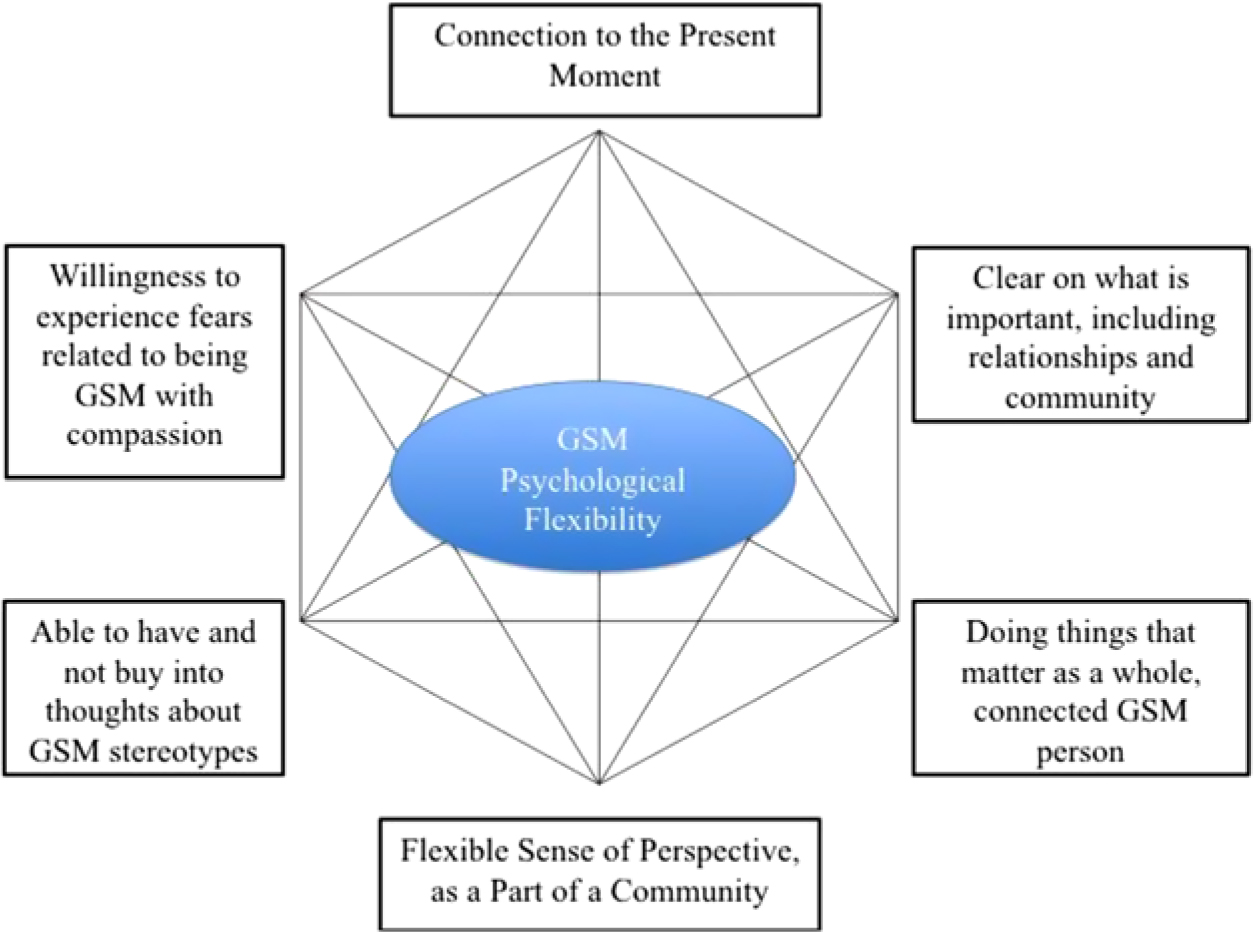

Minority stress and the psychological inflexibility hexaflex

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and compassion-focused therapy (CFT) are approaches within the cognitive behavioural tradition that we have found useful when working with GSM clients (Skinta et al., Reference Skinta, Lezama, Wells and Dilley2015; Skinta and Curtin, Reference Skinta and Curtin2016). An ACT hexaflex (i.e. the name given to the hexagram that maps out the six core processes of the psychological flexibility model) illustrating a specific GSM psychological flexibility clarifies what this might look like (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The psychological flexibility hexaflex for gender and sexual minorities (Skinta and D’Alton, Reference Skinta, D’Alton, Skinta and Curtin2016).

Psychological flexibility can be described as the result of the six core processes of ACT, delineated in the hexaflex in Fig. 1. The goal is that the individual will be able to interact with the environmental and internal experiences flexibly, and will be able to celebrate a variety of domains of the self as a whole person (Farhadi-Langroudi et al., Reference Farhadi-Langroudi, Sargent, Masuda, Skinta and Curtin2016). Specifically, this requires Muslim GSM clients to be present-minded – gaining asylum, for instance, is only beneficial when a client is able to notice that prior dangers are no longer present. Furthermore, perspective-taking allows Muslim GSM clients to connect with the perspectives of the Muslim community in the new host country, which may be more culturally and theologically diverse, as well as a gay community that involves differing religious and cultural histories (Yavuz, Reference Yavuz, Nieuwsma, Walser, Hayes and Tan2016). The second author of this article, M.D. Skinta, for instance, often recommends Abdullah Taïa’s An Arab Melancholia to clients as a path to more deeply connecting with the fact that even in the role of immigrating, dating cross-culturally, doubting one’s faith, or remaining connected to one’s family, this is an experience that connects the client to others and does not isolate them (Taïa, Reference Taïa2012). The role of a compassionate ACT therapist is to foster the type of courage that allows for risking rejection and trying new, frightening behaviours such creating a community and advocating for their own Muslim GSM community, and advocating and educating loved ones about their unique identity without fusing with thoughts about the risks or fears involved or needing those fears to go away before taking risks. Finally, thriving requires that a client identify the sort of person they wish to be, both in terms of identifying and then acting on embodying the identity of a proud, gay Muslim.

The greatest challenge to overcome is often fusion with hostile and threatening external messages (e.g. rejections by religious leaders, stigmatized by culture, loss of masculinity or femininity), as well as those that have become internalized (e.g. ‘I cannot ever be loved by Allah’, ‘I should not exist’, etc.). In ACT, the client is guided to be in touch with these layers of their internal and external environments and how believing these messages serves them, or the impact these messages have on their behaviour across contexts (Farhadi-Langroudi et al., Reference Farhadi-Langroudi, Sargent, Masuda, Skinta and Curtin2016; Skinta, Reference Skinta and Masuda2014).

ACT and CFT both overlap in terms of treatment goals (Tirch et al., Reference Tirch, Schoendorff and Silberstein2014). In CFT, a series of techniques and psychoeducation assist the client to cultivate a self-compassionate perspective on their own life, with specific attention to fears in giving compassion to or receiving it from others, or giving and receiving self-compassion. A self-compassionate perspective allows the GSM client to be in touch with the external and internal suffering that is caused by unfair systems around them. Self-compassion can also empower the person to take meaningful action towards a journey that promotes overcoming the suffering, and promotes soothing emotions (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010).

Self-compassion assists the person to change their internal dialogue from a self-critical to a self-compassionate one. While self-criticism tends to function by leading an individual to feel disempowered, hopeless and pessimistic, self-compassion helps the person to become empowered, hopeful and pragmatic. It is important to note that the goal of self-compassion is not solely the positive outcome per se, but is part of a process in which the person can be in touch with the suffering and unfairness around them and in the same time walk towards a solution that is addressing the source of suffering (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010). This self-compassionate perspective helps the person to live an experiential life beyond the self-critical experience within their mind. Furthermore, the elements of self-compassion highlighted by Neff (Reference Neff2009) – mindfulness, common humanity, and self-kindness – can be evoked within ACT’s emphasis on acceptance, defusion, and perspective-taking in the present moment (Yadavaia et al., Reference Yadavaia, Hayes and Vilardaga2014). The GSM community in Islamic cultures is pioneering the modern dialogue within the Islamic diaspora and the world, which traditionally avoids the conversation and identity of these individuals. A Muslim GSM person will have often encountered external factors such as stigmatizing beliefs or discrimination within their own culture as well as in other cultures (e.g. Islamophobia). These individuals are cultivating an identity which is unique, resilient, and until recently has been denied to be actively part of humanity. The clinician’s goals in this context are to assist individuals to not only face the challenges and stigma externally and internally, but to look at this unique identity within the context of resilience and Islamic values that promotes these unique qualities.

Acceptance and compassion vignette

This following case study illustrates some of the challenges gay Muslim men face in attempting to form new, vulnerable, romantic relationships. It also highlights the way in which a therapist can help clients to navigate those challenges and the accompanying shame associated with them.

As gay social gatherings are forbidden or criminalized in most Islamic countries (e.g. recent crackdowns in Egypt; Bernstein, Reference Bernstein2017; recent increase in arrests in Indonesia; Hutton, Reference Hutton2017), many gay men use online websites and mobile applications that utilize geo-location on smart phones in order to find sexual or romantic partners. This is done with caution, however, and often, after finding a compatible partner, those men might avoid seeking out others. One gay Muslim man described to the first author, with regard to the shifting cultural context of moving to the USA, ‘When I lived in Egypt, an intense flirtation involved too-long eye contact at a café. Now, a man might approach me immediately and ask about sex.’ Western, white gay men are often unprepared for the quick expression of romantic desires or emotional vulnerability, leading to a cycle of rejection and hurt when gay Muslim men find themselves not fitting in, not being called back after sexual encounters, or being rejected by men that seemed eager and excited to explore a relationship only a short time before.

Osama is a 32-year-old gay Syrian man. He moved to the USA 3 months ago to visit a family friend. However, he decided to stay in the USA and apply for asylum due to the war in Syria and wanting to regain his sense of freedom. Osama has never had a long-term romantic relationship and feels unsuccessful because he has not found ‘the right guy’. He has told his gay friends that he is exclusively ‘a top’, meaning he prefers the penetrative role. However, he finds himself enjoying being the ‘bottom’, or receptive partner. Osama finds this shameful, and describes himself as ‘less than a man’ to be the bottom. He is currently dating an older, white American man, Donald. Osama is also living with Donald as he cannot work until he receives his work permit. Osama is not out to his family and his relatives. Osama sought help at the GSM community mental health setting after seeing an advertisement online. His chief complaint is that he feels a great deal of love for Donald and thought that this relationship might be permanent, although Donald has expressed a desire for an open relationship and has seemed put off by what he describes as Osama’s possessiveness. He was also fearful of contracting a sexually transmitted infection or HIV, and afraid of the possibility that his family friends would learn that he is gay. Osama reported having panic attacks about affecting his family’s honour negatively by being known as a gay man. The following dialogue is an excerpt from a therapy session between Osama and the first author (Khashayar):

Osama [O]: I wish I was never born! I dunno why I am gay!

Khashayar [K]: What makes you say such a harsh comment toward yourself? [Able to have and not need to believe thoughts about GSM stereotype, noticing self-critical thoughts]

O: I am in pain! I think I am a good person and love others. But, I am not sure I will ever be loved by anyone. If my family and friends find out I am gay. I will lose all the respect that I have obtained by this point.

K: Can I encourage you to tell me where do you feel pain the most in your body? [Connecting to present moment]

O: It’s all over my body, but mainly in my heart.

K: Can I ask you to put your hand on your heart and close your eyes and lower your gaze and focus on this pain? [Willingness to experience fears related to being GSM with compassion, blocking avoidance of painful emotions]

O: Ok, I think I am going to close my eyes as well.

K: Now, I want you tell me what do you feel, see, in the space between your heart and hand? [Willingness to experience fears related to being GSM with compassion]

O: I feel there is big burden on my heart; it might keep me from breathing.

K: Can I ask you when the first time you experience this feeling was? [Clear on what is important, including relationships and community]

O: I remember it vividly; I was 12 years old. It was my first time that I feel I like my classmate, Ahmad. He was very sweet, charming, and friendly. I told Ahmad that I would like us to be close friends. I told him that I wanna be always next to him like married people. I shared my feelings to him. Ahmad had an older brother. He told his brother all that I said. The next day, Ahmad was very cold during school with me as well. He said he does not want to talk with me. I was worried. I felt I did something wrong. But I didn’t know what it was. My heart was racing hard during the class. I knew it, I knew something was wrong with me. But no one told me what was it. I just felt different. At the end of the day, his brother was waiting for me outside of school. He looked at me with anger. He took my hand and took me to a less crowded alley. I was scared and I was shaking. My head was down and I couldn’t look at his face. He pushed my head up and forced me to look at me. He slapped me in the face and told me, if I ever want to talk or play any ‘marriage game’ with anyone he would be sure to tell my parents to kill me. He told me that people like me are disgraced and punished highly by Allah. He told me I was sick and that he would tell everyone about my sickness.

At this point, Osama was crying as he told Khashayar his story, with one hand on his heart and one hand wiping the tears from his face.

K: It is painful how your desire to show your natural emotions as a child led to such a strong negative reaction. Do you think you can sit with this painful emotion for few more minutes? [Willingness to experience fears related to being GSM with compassion, blocking experiential avoidance]

O: It has been with me all these years. I can sit with it a bit more.

K: Now I want you to imagine if you would see that young 12-year-old Osama now. He is scared of others not liking him. He is feeling lonely and separated by others. And he is standing in front of you and craving your kindness and support. What would you say to him? [Flexible Sense of Perspective, practice viewing the world through the eyes of his most compassionate self]

O: I would tell him that there is nothing wrong with him, he is a good child, and he is just different from others. And no one is allowed to judge him until the last day of earth by Allah. I would give him a hug and wish him a safety and prosperity.

K: It sounds beautiful! Do you think you needed that hug and soothing when you were 12? Do you think there is part of you that still craving the warmth and support? [Acceptance and labelling of current emotions]

O: I always do. But no one could give it to me. Because I believed that no one would love me if they know about me.

K: Do you think today you have cultivated this new person in your life? A self-compassionate self that will be there with you, once you put your hand on your heart and start talking with me? [defusion, or working to notice and not necessarily believe thoughts about GSM stereotypes]

O: I can see that there is part of me that understands it wasn’t me and it wasn’t my fault. I hope I can access it more often.

K: Since it is part of you, it will be always there. The inner critic tried to save you in the past from bullies and negative consequences. The inner critic might have a hard time to trust the new self-compassionate voice because they still think you are still only 12 years old! And, we are going to invite the self-compassionate voice to our life like the blissful sound of adhan [the call to prayer] to our daily life. You’re a strong person and a role model, Osama. I’m sure we can help this part of you flourish. [Clear on what is important, including relationships and community, and doing things that matter as a whole, connected Muslim GSM person]

In this session, the ACT therapist assisted Osama in exploring his distress regarding the intersection between his sexual orientation and his cultural identity. Using the ACT hexaflex for gender and sexual minorities, the therapist tried to engage and assess for different factors that impact of psychological flexibility. The client was encouraged to experience his fears, he was willing to experience fears related to being GSM with compassion, and also willing to examine the thoughts and the possibility of not needing to buy into thoughts about GSM stereotypes in his culture. The client was invited to practise mindfulness to connect to the present moment and take a flexible sense of perspective as a part of a community of Muslim GSM people, promoting both mindfulness and a sense of common humanity. The client was directed towards assessing his values, obtaining clarity on what was important to him, including relationships and community. He was also invited to consider doing things that mattered to him as a whole, Muslim GSM individual, as an expression of self-kindness.

Future directions

While the approach described above is theory-driven and provides a strong starting foundation, the limited empirical base supporting these interventions suggests a number of paths forward. First, in the absence of randomized controlled trials, single-case designs may allow for further refinement of the model and the identification of additional treatment needs in this population (e.g. Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2011). This may provide needed support for the development of protocols that then might be further explored within randomized controlled trials developed specifically for Muslim GSM clients, and a refinement of those cultural elements most beneficial to reducing the impact of intersectional biases such as homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, Islamaphobia and racism, particularly given the lack of prior clinical literature on work with Muslim GSM clients.

Furthermore, this presumes the presence of sensitive, highly trained clinicians. Effective interventions with GSM members of the Muslim diaspora require sensitivity to culture, access to the population, and familiarity with norms both within and outside the local GSM community. Research into topics such as sexual racism and their impact on physical and mental health, sexual practices and HIV risk, and well-being is still new and requires a variety of methodological approaches to expand limitations of the existing literature. Similarly, developments into the effective treatment of racial trauma might also inform how best to improve existing protocols, as many Muslim individuals are also people of colour (e.g. Williams et al., Reference Williams, Malcoun, Sawyer, Davis, Bahojb-Nouri and Leavell Bruce2014).

Conclusion

Just as in other cultures and nations of the world, there are gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender individuals who were raised in the Muslim faith in Islamic nations. The challenge is to create a context that promotes a healthy identity for those struggling to reconcile their sexuality with their culture, community and faith. Shame is experienced as a negative emotion that only arises in a social context – we learn what to be ashamed of and what jeopardizes our risk of social rejection, as well as the social roles that expose us to experiencing shame. Muslim GSM individuals are doubly harmed by this process, experiencing shame and stigma arising from biases within Muslim communities, Islamaphobia, racism, as well as experiencing homophobia within majority Western communities, and Islamaphobia and racism within Western GSM communities.

Muslim GSM individuals have historically been misdiagnosed and stigmatized within the clinical world (e.g. Zucker and Spitzer, Reference Zucker and Spitzer2005). Clinicians have used content-dependent diagnosis such as depression or anxiety due to personal factors, or identities such as belonging to an ethnic minority or being a father. It is important for clinicians to remember that the connectedness with shame that might exist with a Muslim GSM individual is a shared suffering that their client is not experiencing alone. Therefore, it requires the clinician to be self-aware of their biases, and then to try to create a safe, compassionate space for the client to create a context-dependent psychological flexibility. A context-dependent psychologically flexible space is one in which the client can allow the emergence of their complex identities through the care of their own self-compassion. This space is then not only healing for the client, it also promotes psychological flexibility for the clinicians.

We have attempted to shine a clinical light on a population that has been historically neglected and been consistently denigrated, due to its unique way of being. Islamic communities since their earliest beginnings have been open to integrating a variety of minorities and marginalized populations (e.g. women, people of colour, Christians, Jews, etc.). With the internet, as well as the patterns of global immigration among Muslim communities, this seems to be a moment in time when the emergence of those with Muslim GSM identities can become more visible and engaged in the conversations of others. A Muslim GSM individual can create an identity rooted in pride in both the richness of their religion and unique cultural ways of being that embrace all parts of their self.

Author ORCID

Matthew D. Skinta, 0000-0002-2365-6323

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the all the GSM Muslim refugees and clients that have shared their lived experiences with us. We would also like to thank Dr J. Allison He for her careful proofreading of the completed manuscript.

Financial support

No specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors was used in the preparation of this paper.

Conflicts of interest

Khashayar Farhadi Langroudi and Matthew Skinta have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Key practice points

(1) There is limited clinical guidance in peer-reviewed literature regarding effective responses to the needs of GSM clients from Muslim diaspora nations.

(2) Acceptance and compassion-based approaches align well to the clinical needs and cultural backgrounds of GSM Muslim clients.

(3) Muslim GSM individuals can create an identity that compassionately embraces the richness of their religious background, sexual orientation, gender identity, and unique cultural ways of being.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.