An actor sits alone on a bench. She picks up the doll beside her with one hand and with the other begins drawing objects in the air with her index finger. One of the musicians onstage accompanies her actions with a slide whistle providing a playful soundtrack to the atmosphere of childlike discovery. First the girl draws a window that she opens and looks out of, next an ice cream cone she mimes eating with delight. Soon the adult actor playing the young girl is joined by a second young woman who plays the role of an older child, a teenager. The second actor is dancing casually to the music she listens to on her phone. Seeing the child alone, she takes off her headphones, sits down on the bench, and tries to strike up a conversation. She asks the child how old she is; the girl counts five fingers to indicate her age. “Why don’t you talk?” the older girl asks. The child answers through hand motions that she does not have a voice. “Do you want me to teach you?” the child’s new friend proposes. The young girl nods enthusiastically, and with this the two set off upon a surprisingly poignant journey towards language acquisition, represented in performance through the rhythmic incantation of individual letters and syllables. This memorable and moving sequence is accompanied by live music and shows the two girls center stage as they joyfully jump, dance, and chant in unison stringing together sounds until arriving, at last, at the child’s first full word: “Mama” (Lishchuk Reference Lishchuk2017).Footnote 1

Figure 1. Student playwrights from Class Act: East-West bid each other farewell after completion of the program. Kyiv-Pasazhyrskyi railway station, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

In the next scene the young girl, now able to speak fluently, explains in a monologue to the audience how she learned to speak at the age of five, and only with the help of her older friend Sophia. Written in 2017 by 15-year-old playwright Tetiana Lishchuk from the small city of Klesiv in the west of Ukraine, this 10-minute play is based on the author’s own experience as a child. In the play’s final scene, the girl, who remains nameless in the script, is shown six years later corresponding with Sophia, who has since moved away and will soon be graduating from college. Sophia is busy with her friends and with her classes but assures the girl that she misses her. “Shall we meet sometime soon?” the young girl writes to Sophia. “Yes, let’s,” Sophia responds. “When?” the younger girl asks, but there is no response. The lights go out. The play is over.

Lishchuk’s play and the ambiguity of its final moment offer an important reflection on the intricacies of the cultural and historical moment in which it was performed. The play is entitled Holos, a Ukrainian word that can be translated as both “voice” and “vote.” An eloquent and haunting text, Holos was featured in the second iteration of a Ukrainian youth theatre project called Klass Akt: Skhid-zakhid (Class Act: East-West). In the years between Ukraine’s Euromaidan Revolution (2013–14) and Russia’s full-scale invasion of the country on 24 February 2022, the nation witnessed an incredible boom in socially engaged performance practice. Enlivened by a new sense of political agency, Ukrainian theatre-makers from across the country began seeking out unusual and innovative approaches to imagining and articulating a more inclusive, coherent, and pluralistic vision of civil society. One key element of this theatrical revolution was an increased interest in youth theatre, particularly the participation of young people in the eastern region of Donbas, one of the areas that has come under the fiercest fire since the intensification of the war in recent months.

Russia’s current attack on Ukrainian sovereignty is a horrific escalation of the war that began in 2014 when separatists with the support of Russian proxies tried to establish two breakaway territories along Ukraine’s eastern border. Between November 2013 and February 2014, over 2 million Ukrainians took to the streets during the Euromaidan Revolution in defense of democracy, human rights, and economic transparency. These protests led to the ousting of Russia-allied president Viktor Yanukovych in February 2014, immediately after which Russia began the process of illegally occupying the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea. Within weeks of Russia’s illegal and illegitimate “referendum” in Crimea, war broke out in Donbas as the Kremlin funneled in both arms and troops to fuel a covert conflict between the Ukrainian army, the Russian army, and a disparate group of separatists in the region. What was for years referred to as a “frozen war” had already claimed over 14,000 lives and displaced close to 2.5 million people before the Kremlin’s murderous attack on Ukrainian cities and residential areas across the country began in February 2022 (OHCHR 2021).

Set within the context of these ongoing events, Class Act: East-West was a series of playwriting workshops for teenagers created by Ukrainian writer-director Natalka Vorozhbyt in collaboration with Scotland-based writer Nicola McCartney. The series ran annually in Kyiv for three years from 2016 to 2018. Each year the Ukrainian project organizers visited a different school in eastern Ukraine as well as one in western Ukraine to run a series of writing workshops for students. The schools were chosen based on Vorozhbyt and her team’s previous connections to these areas and, in the case of cities in the east, their geographical proximity to the front line. Footnote 2 At the end of these local workshops, students who were interested in participating in the program in Kyiv submitted short essays and final participants were selected based on these writing samples.

After arriving in Kyiv for the program, students took part in a series of workshops Footnote 3 on the basics of dramatic structure before submitting proposals for the short plays they wanted to write. Proposals were then reviewed by the team of professional playwrights who served as mentors. Students who proposed plays on similar themes were paired to write collaboratively; others wrote solo. All of the students were assigned mentors from the group of playwrights who had joined the project that year. At the end of their 10 days together, the students’ texts were staged for the public at a gala performance featuring many of Ukraine’s most acclaimed actors, directors, and designers. The styles of the plays varied; melodrama was a popular genre chosen by the students, but comedies and abstract absurdism were also well represented. In short, the students wrote in the styles that spoke to them and on the topics they deemed most relevant to their everyday lives.

Class Act: East-West was created in direct response to Russia’s war against Ukraine and the divisions it fostered among people in different parts of the country. Part of the project’s aim was to dispel the common and divisive stereotypes about “Ukrainian-speaking fascists” from the west and “Russian-speaking separatist sympathizers” from the east. Such destructive cultural narratives built upon a history of Soviet colonialism and were frequently perpetuated through Kremlin propaganda between 2014 and 2022. In truth, Ukraine is a multilingual country. Many people in eastern Ukraine speak Russian as their first language and many people in western Ukraine speak Ukrainian. However, these divisions are not rigid categories and the languages someone chooses to speak in Ukraine are not a reliable determinant of their political affiliations.

Adapted from a model first developed at the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh in the 1990s (Williams Reference Williams2022), the Ukrainian version of Class Act was built to facilitate dialogue and encourage understanding between students in eastern and western Ukraine, all of whom were living with the consequences of the war in different ways. An additional aim of the program was to inspire a new generation of theatre artists and audiences from small cities and towns across the country. Alongside these two goals, my research reveals that Class Act: East-West also played a crucial role in the realization and development of Ukraine’s vibrant culture of new playwriting and political performance practice in the years since the Euromaidan Revolution.

As a volunteer for the project in 2017/18, I had the opportunity to get to know the students in the program; to observe workshops, rehearsals, and performances; and to work closely with the team of volunteers and theatre professionals who made the project possible. Footnote 4 Having written previously about political performance in Russia, my work on Ukrainian theatre began in the years after Euromaidan as it became clear to me that the work coming out of Ukraine at that time was at the forefront of socially engaged performance practice, not only within the former Soviet region, but also internationally. As a participant and a researcher of Class Act: East-West, I observed the complexities of the project’s regionally specific social intervention as well as its global relevance as an innovative example of 21st-century political theatre.

What purpose did Class Act serve for the students and for the professional participants? How did the project’s social aims impact its aesthetic innovations? And to what extent did the program’s emphasis on language, narrative, and self-expression facilitate an exceptionally generative space for a more inclusive, coherent, and autonomous imagining of contemporary Ukraine?

Finding a Common Language

Holos was performed three years after the Euromaidan Revolution, a major turning point for Ukrainian society. What began as a peaceful protest against former president Viktor Yanukovych’s allegiance to Russia gradually came to reflect a more encompassing set of core values; a surprisingly diverse group of citizens and activists came together in defense of economic transparency, independence, and human rights. The peaceful protest movement later erupted into violence as Yanukovych sent Ukrainian riot police to intimidate and brutalize protestors. In February 2014 this violent crackdown against citizen activists reached a terrifying peak when 104 unarmed civilians were killed, many of them gunned down by sniper fire just around the corner from the theatre where the Class Act plays were later staged (RFERL 2020).

In this cultural and historical context, Holos offered insight into a complex of issues at the center of the country’s cultural discourse. As Ukraine grappled with the aftermath of the revolution, including the ongoing war in its eastern territories, the topics of voices and voting were at the heart of a crucial conversation about democracy and civil society. The process of learning to speak out, the ability to make one’s voice heard, and the capacity to employ language as an instrument of self-understanding and self-definition were some of the themes Lishchuk’s play spoke to.

There is a disarming dissonance to watching adult actors playing children onstage in Holos, a discord that is felt to some extent in all of the Class Act plays: adult actors speak the lines we know were written by teenagers. The seeming simplicity of the plays takes on new resonance as audience members are implicitly asked to reconcile the childlike innocence at the center of the texts with their often intricate and occasionally unnerving associations in performance.

In the 2016 play Lishniaia zhertva (Personal Sacrifice) by Yaroslav Cherkashenko, a teenage boy named Fedia is a disappointment to his mother, not least of all because he is a vegetarian. At the start of the play Fedia has cooked his mother dinner to which she responds,

MOTHER: Again without meat? […] I wake up and go to work every day to buy this meat. I can’t remember the last time I went on vacation. I work, I exhaust myself to feed and clothe you and you don’t even want to get a job. All my friends are getting manicures, haircuts, and makeup but I don’t have time for that […M]y skin is as dry as a stale piece of bread! (Cherkashenko Reference Cherkashenko2016)

She goes on to berate Fedia about all of the ways he has disappointed her. Fedia attempts to defend himself, citing the inhumane treatment of animals raised for slaughter, but with no success. “My whole life I’ve been sorting through textbooks, and never once have I even been to the Hermitage museum,” she concludes. “What, that one in St. Petersburg?” Fedia dryly responds.

Later in the play, Fedia suffers more harassment from his macho classmates who mock his concern for animals and his ethical stance against eating meat. One boy even offers him $1,000 to eat a steak. Fedia discusses the proposal with his fellow vegetarian friends who are appalled that he would even consider it. They assure him they will no longer be his friend if he goes through with it. In the end though, Fedia agrees and even allows his classmates to take a video of him as he takes that first bite of meat. Afterwards he returns home and gifts his mother two tickets to the Hermitage museum (Cherkashenko Reference Cherkashenko2016).

Like many of the Class Act plays, there is a youthful naivete inherent to the language and the narrative of Lishniaia zhertva. Yet the play also portrays nuanced relationships and an intricate set of ethical questions. In performance the actors give over to the text’s seeming simplicity. They speak the lines with sincerity but also with a distinct sense of distance. In doing so their performances invite audience members to reconcile their perhaps more cynical adult understanding of the text and the struggle it portrays, with the innocence and clarity of the author’s voice. In the case of Lishniaia zhertva, a conflict between personal values and personal loyalties echoes beyond the circumstances portrayed onstage, particularly in an environment in which many people have friends and family members on the front line or, at the age of 15 or 16, are already anticipating what it would take to make the decision to take up arms themselves.

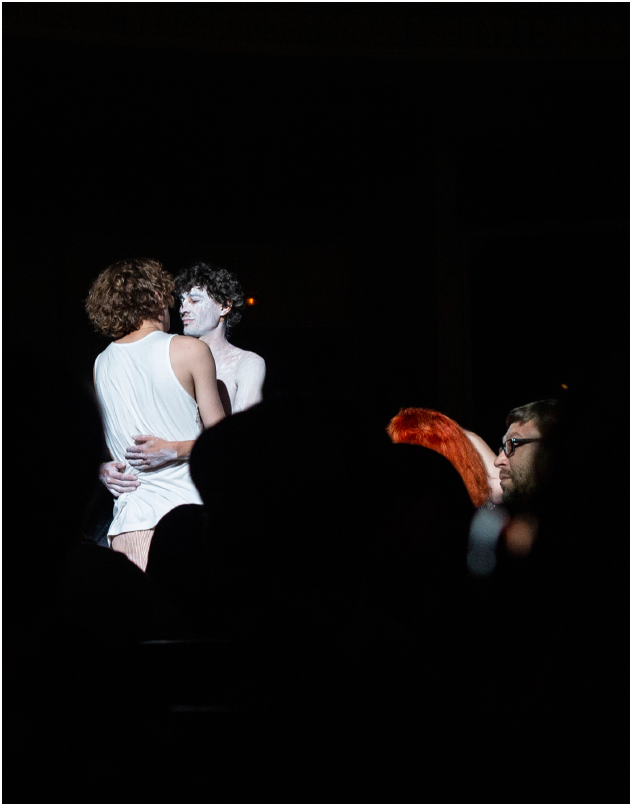

Figure 2. Z liubov’iu, pryvyd (With Love, from a Ghost) by Anna Husak, directed by Dmytro Zakhozhenko. From left: Kostiantyn Temliak and Volodymyr Minenko. Ukrainian Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music, Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

Some of the other topics portrayed in the Class Act plays rarely if ever seen on major stages in Ukraine at that time include loneliness, bullying, abortion, poverty, and homophobia. Of particular note was the romantic and dramatic kiss between two young men in the 2018 Class Act play Z liubov’iu, pryvyd (With Love, from a Ghost) by Anna Husak, which was anecdotally believed to be the first instance in which a gay relationship was openly portrayed on the stage of any state academic theatre in Ukraine. Alongside these personal and political topics, there was one theme that few plays featured explicitly, though all were haunted by in one way or another: the private and public consequences of Ukraine’s ongoing war with neighboring Russia.

Throughout the war waged by the Kremlin and its proxies consistently since 2014, the term “hybrid warfare” was frequently used by policy makers and security specialists to describe Russia’s war in Ukraine before the full-scale invasion, when its atrocities began to dominate the global public imagination in new ways. “Hybrid warfare” describes the battles during the first eight years of the war that were fought not only between Ukrainian and Russian soldiers, volunteers, and separatists at the front line, but also in remote attacks on Ukrainian state infrastructure as well as the propagation of disinformation. Other terms used to describe Russia’s multifaceted attacks on Ukraine since 2014 include “information warfare,” “nonlinear warfare,” and “anthropological aggression” (see for example Paziuk Reference Paziuk2020; Schnaufer Reference Schnaufer2017; Boroch and Korzeniowska-Bihun Reference Boroch and Korzeniowska-Bihun2021). Although nuanced in their own right, each of these terms shares a common intent, which is to decipher and describe how the Kremlin fabricated and distributed disinformation in an attempt to deepen divisions in Ukraine and generate an attitude of scepticism towards the state and its institutions.

One such example has been Putin’s unfounded and delusional notion that Russia needed to “protect the Russian-speaking population of Ukraine” (Matviyishyn Reference Matviyishyn2020). This is a lethal and misguided assertion that implicitly revealed the Kremlin’s role in what Russian officials frequently and purposefully misidentified as a “civil war” in Ukraine, thereby denying Russia’s role in the conflict until the 2022 invasion. Notably, the Kremlin still has not identified its actions in Ukraine as a war and has begun prosecuting anyone who publishes anything other than the party line, which identifies the invasion as a “special military operation” to “denazify” Ukraine (Troianovski Reference Troianovski2022). In fact, electorally, the far right makes up less than two percent of the Ukrainian parliament, significantly less than other European countries such as Hungary and Poland, which have both seen a rise in ultranationalist political presence in recent years (Shekhovtsov Reference Shekhovtsov2021). And in this multilingual country, the majority of the population is conversant in both Ukrainian and Russian. While some Ukrainians feel more comfortable speaking one language than the other, in many parts of the country it is common for people to switch between the two throughout the day or even within one conversation. As Rory Finnin and Ivan Kozachenko describe, Putin’s claims to defend the rights of Russian speakers in Ukraine

pivot on the reductive notion that language use determines political identity in Ukraine; on the stale notion that there is a bounded, coherent constituency of Russian-speakers in the country; and on the absurd notion that they are somehow under threat from a Ukrainian state whose wartime presidents—Oleksandr Turchynov, Petro Poroshenko, and [Volodymyr] Zelens’kyi—are all native Russian speakers. (2020)

Such falsehoods about identity and language were deployed to encourage fear and discord by igniting and enlivening divisive cultural stereotypes between east and west Ukraine. This is one facet of the war and the rhetoric that surrounds it that Class Act: East-West was particularly adept at confronting. Students were free to write about the topics that interested them most in the language of their choice. In the first year of the program about half the plays featured the war as a central thematic or contextual plot point. In 2017 only one of the plays told the story of someone explicitly impacted by the war. In 2018 not a single play featured direct reference to Russia’s war against Ukraine.

In the 2016 play Na puantakh (En Pointe), a young dancer named Nicole argues with her mother who has forbidden her to leave her house in east Ukraine to attend her dance lessons while their city is being shelled. “But mom,” Nicole responds, “dancing is my addiction and I’ll never be cured of it.” Her mother replies, “Have you forgotten what happened to your father? Do you want me to end up completely alone?” “Let’s not talk about Dad,” the girl says, “He’s never coming back.” Despite her mother’s pleas, Nicole sneaks out of the house to go to her dance lesson where she suffers a mild injury to her leg when a nearby building is shelled, the impact of which shatters the windows in her dance studio.

In the next scene the girl pleads with her mother to move away from the war zone in the east to Kyiv where she can study to become a professional ballet dancer, but Nicole’s mother is reluctant to relocate. “Where will we go? You think they’ll be waiting for us with open arms? You think anybody wants us there? We won’t have a home, and I won’t have a job!” (Kruhlova and Stryzhkova Reference Kruhlova and Stryzhkova2016:3). In these lines we observe some of the underlying tensions and divisions the war provoked between people from different parts of the country and among different generations between 2014 and 2022.

Most of the students who traveled from eastern Ukraine spoke Russian as their first language. Those who traveled from the western part of the country spoke Ukrainian. Workshops were run in both languages and everyone was invited to use whichever language they felt compelled to speak at any given time. All three years saw about half of the plays written in Russian and half in Ukrainian, alongside several plays that used both. Language was fluid in the Class Act learning environment, as it is in Ukraine, and was not a source of tension for the students.

Figure 3. Iak zdykhatys’ diad’ka (How to Get Rid of Your Uncle) by Anastasiia Zikova and Valantyn Kravchuk, directed by Dmytro Zakhozhenko. From left: Lilia Tsvelikova, Oleksiy Vertyns’kyi, and Vitaliy Azhnov. Ukrainian Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music, Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

In a 2016 documentary about the initiative, project creator Natalka Vorozhbyt is shown walking through a room checking in with pairs of energetic and enthusiastic teenagers working away on a writing assignment. Shouting above the loud hum of voices, one student calls out to her, “In which language are we meant to be writing?” to which the playwright swiftly and decisively responds, “In your own” (Tolmachev Reference Tolmachev2016). This response speaks volumes about how the program creators deftly circumvented the regionally specific notion of languages as politically divisive and instead succeeded in harnessing the power of language as an essential instrument of self-expression and self-definition that can be deployed to create a sense of connection rather than deepen divisions.

As one 15-year-old project participant, Anastasiia Zikova, described her experience at the time, “I had a prejudice towards people from Western Ukraine. So do my parents. They think fascists and radicals are there” (in Makarenko Reference Makarenko2018). Having arrived from the eastern city of Avdiivka, one of the areas that has been targeted by Russia’s 2022 attacks, Zikova was paired with Valentyn Kravchak from the western city of Chop. Together the two wrote the comedy Iak zdykhatys’ diadka (How to Get Rid of Your Uncle), a play about a brother and sister who are preparing to sell their family home in western Ukraine near the Carpathian Mountains after their parents have passed away. Their domineering uncle, played by Oleksiy Vertyns’kyi, an actor well-loved throughout Ukraine for his comedic work in both film and television, shows up and complicates their plans.

With bombastic presence and incredible comedic timing, Vertyns’kyi institutes a strict regime of morning calisthenics and other unbearably annoying house rules. Together the siblings devise a series of pranks to irritate their uncle and drive him out of the house. Hilarity ensues and he eventually storms out claiming, “I’d rather live in my Khrushchevka apartment Footnote 5 outside Zhytomyr, than here with you!” (Kravchak and Zikova Reference Kravchak and Zikova2018:4). After their uncle’s departure, the two siblings realize that they have grown closer through their efforts to get rid of him. They also come to see the value of shared space and a family home and, in the end, decide not to sell the house. Through the process of writing the play, Zikova says, she and her writing partner “found a common language” (in Makarenko Reference Makarenko2018).

Figure 4. Iak zdykhatys’ diad’ka (How to Get Rid of Your Uncle) by Anastasiia Zikova and Valantyn Kravchuk, directed by Dmytro Zakhozhenko. From left: Vitalii Azhnov, Oleksii Vertyns’kyi, and Lilia Tsvelikova. Ukrainian Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music, Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

Another Class Act: East-West participant, also named Anastasiia, tells a similar story. Coming from the western city of Klesiv in 2017, Anastasiia Trishchuk worked together on a play with Daniil Volkov from the eastern city of Shchastia. Trishchuk describes how upon arriving in Kyiv she thought she would have trouble communicating with the students from Shchastia. “At first I didn’t understand why we were paired together because we were so different,” she says, “but then we worked well together, and we became friends” (in Radio Hayat 2017). Volkov and Trishchuk wrote Tantsor (The Dancer) about Egor, a boy who, like a surprising number of the protagonists in the Class Act plays, was being raised by his grandmother. Egor’s grandmother adored dancing as a young woman and dreamed of her grandson becoming a dancer. Although Egor did not share his grandmother’s passion, he sought out an instructor and learned to waltz so he could offer his grandmother the chance to dance together in her favorite spot in the park as a parting gift before she moved abroad for work. In the final scene of the play, Egor and his grandmother dance a waltz in a symbolic moment of cross-generational love and appreciation. Speaking about her experience of writing Tantsor together with Volkov, Trishchuk reflects, “We are all the same. We have the same problems with school, with parents. We are all teenagers” (in Radio Hayat Reference Hayat2018).

In their 2021 article on the social and political impact of Class Act: East-West, Robert Boroch and Anna Korzeniowska-Bihun illustrate how the project served to counteract propaganda and bridge cultural and linguistic divisions between the teenage participants. Their analysis of the initiative hinges on the notion of “anthropological aggression.” This is a concept developed by anthropologists to describe a scenario in which one social group commits violence against another, with the explicit aim of structural domination in the realm of information and ideology as represented through media, education, economic policy, et al. (see also Kelly Reference Kelly2000 and Otterbein Reference Otterbein2009). Boroch and Korzeniowska-Bihun suggest that by bringing teenagers together to work creatively and collaboratively, Class Act: East-West came to constitute a form of anthropological defense. The project helped students to see one another as individuals, rather than as representatives of one social group or another. The dehumanizing effects of Russia’s anthropological aggression began to recede and an emphasis on mutual understanding was fostered through the collaborative process. The project’s emphasis on self-expression created the space for an emergent community in which individual and diverse voices were valued as essential elements of a larger whole.

As Boroch and Korzeniowska-Bihun argue, and as the examples above clearly illustrate, the friendships forged between students through participation in Class Act constituted an integral element of the project’s political and social intervention. What may have seemed like insurmountable differences between students at the start were soon overshadowed by commonalities that united them as teenagers, as Ukrainians, and as playwrights. The necessity to work together and to articulate their experiences through the craft of playwriting required of the students an ability to listen and respect one another as individuals, not as stereotypes. Through their creative collaborative practice the students overcame both real and imagined differences and focused instead on what they shared (Boroch and Korzeniowska-Bihun Reference Boroch and Korzeniowska-Bihun2021:134–35).

“And then you realize, it’s actually genius”

In addition to facilitating meaningful social connections, Class Act: East-West was designed to teach participants how to write a good play, to build an awareness of dramatic structure, and in doing so, to deconstruct the process of building an engaging narrative. These skills are among those that I suggest lent the project particular efficacy, as they provided participants with new agency and the skills to shape and articulate their own stories. In Ukraine’s postcolonial context, the capacity to take ownership of one’s own story and apprehend the power of language to do so is no small thing. This is one of the reasons that the program’s focus on writing was of particular importance in its specific cultural context.

Its singular emphasis on playwriting as the central focus of the project is one element that distinguishes Class Act from many other forms of educational and applied theatre in conflict zones. As James Thompson, Jenny Hughes, and Michael Balfour discuss in their pioneering research on theatre and war, performance can play an important role during times of crisis. In their 2009 collection Performance in Place of War, these authors establish an essential frame of reference for considering theatrical interventions in the context of cultural and political violence. As their work illustrates, such practices most often draw upon improvisation, role-playing, and autobiographical storytelling to facilitate collective processing of cultural traumas.

Class Act: East-West also employed performance practices to bridge cultural divisions and create space for dialogue. In distinction to the projects analyzed in Performance in Place of War however, Class Act drew upon the craft of writing as its primary intervention. In doing so the initiative shifted its focus away from the notion that participants were expected to perform their own stories and instead reoriented attention towards an awareness of how stories are told. Such an unusual emphasis on narrative structure and playwriting is one of the features the program inherited from its original incarnation as created by a group of playwrights and producers at Edinburgh’s Traverse Theatre in the 1990s, where it has been running with great success ever since.

In Scotland’s Class Act program, professional playwrights visit schools to work with students once a week over the course of several months to develop scripts for 10-minute plays. Their plays are subsequently showcased by professional actors in staged readings for invited audiences of friends and families. At the core of the Class Act ethos is a belief that teenage playwrights are capable of telling stories worth hearing. The project was built to inspire young people in Scotland as creative individuals and to generate national interest in the performing arts. It is an educational program that has, over the course of three decades, proven extremely effective at building confidence and promoting literacy among its teenage participants. Footnote 6

The model was introduced to international audiences in 2004 when UK theatre-makers Nicola McCartney, Douglas Maxwell, and Jemima Levick ran a revised version of Class Act in the western Russian city of Togliatti. As researcher and Class Act facilitator Maria Kroupnik describes in detail, the Traverse team worked together with a group of Russian playwrights who learned the methodology through their work on the project. Footnote 7 These local playwrights have since shared the Class Act approach with several generations of Russian theatre-makers who have continued to run different versions of the program all across the country. As distinct from the Traverse model, the Russian versions of Class Act have students and mentors working intensively for five or six hours a day over the course of one or two weeks as opposed to the term-long model developed in Scotland. Also, in Scotland the program is run in coordination with the local school curriculum, whereas in Russia the project is run as an out-of-school initiative. According to Kroupnik, these adjustments were initially made as a result of limited resources. Freelance playwrights were able to commit to one or two weeks of intensive work more easily than a prolonged program. Likewise, theatre venues were able to host the workshops for shorter periods between public productions. As Kroupnik writes, this intensive model proved “more effective in terms of creating a ‘safe space’ for trust to be built, for fun, and for real equality to develop in the creative process of theatre-making” (2020:87).

Another essential adaptation first implemented in Togliatti in 2004 and since carried out in cities across Russia as well as in Kyiv and in Mumbai in 2018 Footnote 8 was the practice of using the structure to facilitate connections between groups of students from disparate backgrounds. In Scotland, students most often work together with other students from their own class or school group. In Togliatti, teenagers from a local secondary school were paired with students from a nearby orphanage. In this way, the initiative created space for communication between two demographics of teenagers who were living in the same city but with very different circumstances and very few opportunities to socialize outside of the project. Since that time, several Russian Class Act–inspired projects have paired able-bodied students with disabled students. Other versions of the program have seen Russian-speaking students working together with Tatar-speakers in Kazan or, for example, speakers of Buriat in Ulan Ude near the border with Mongolia. As Kroupnik describes, no less than 30 different versions of Class Act have run in Russia since the model was first introduced to local playwrights in 2004, most of which use these types of collaborative structures to build bridges across cultural, political, and socioeconomic divisions.

It was in Moscow in 2009 that Natalka Vorozhbyt first encountered the program. Born and raised in Kyiv, Vorozhbyt studied at Moscow’s Gorky Literary Institute in the late 1990s and played an important role in the development of Russian-language New Drama in the early 2000s before returning to Kyiv and promoting the establishment of several key new playwriting initiatives in Ukraine. While working on Class Act in Moscow in 2009, Vorozhbyt became acquainted with Scotland-based writer, director, and educator Nicola McCartney with whom she has continued to collaborate on several subsequent projects. Footnote 9 McCartney played a key role in developing the Class Act model together with Vorozhbyt for Ukraine, and the two writers ran the program together in its first year.

One commonality among all national iterations of Class Act, including the recent 2018 version in Mumbai, is the fact that the teenagers are treated like professional playwrights; and they are expected to regard one another as professionals. As McCartney says:

We teach them to communicate with each other in a civilised way. To discuss their work without offending one another. Their self-esteem increases and the teenager becomes more mature. The schoolchildren start to learn better. They gain the ability to express their own thoughts—and of course, there is the correcting of spelling… But the main goal remains the same—to write a great play. (Kroupnik 2021:90)

This primary focus on collaborative writing and the mutual professional respect it supports is one of the things that makes Class Act so exceptionally successful.

Likewise, in Ukraine, the quality of the plays as examples of dramatic writing was as central to the ethos of the project as the effort to facilitate dialogue between students from east and west. From my perspective, it was in large part the organizers’ explicit emphasis on the quality of the artistic work that so skillfully created the conditions for mutual respect as a guiding principle of the project.

One of the key differences between the way Class Act was staged in Ukraine in comparison to other countries was the fact that the project’s plays were staged in full by professional actors, directors, and designers in a highly publicized gala event. This difference was of particular significance in Ukraine for two central reasons. First, although every play had its own director, each year’s performances were overseen by a primary director who brought the short plays together into a cohesive vision. Footnote 10 Every year the project also featured a different musical group or artist whose music was a unifying leitmotif connecting all of the individual plays presented. Footnote 11 Additionally, the performance included short videos that were projected on a large screen upstage between each play introducing the play’s title and its authors. Footnote 12 Lastly, the project’s production designer, Maria Khomiakova, masterfully orchestrated coordination of sets, costumes, lights, etc., establishing distinct visual themes that resonated across the short plays.

For example, in the 2018 play Avdiivs’kyi Romeo (Avdiivka Romeo) by Filip Kazlauskas and Evhenyia Kavol’chuk, a young woman named Vasylysa falls for a deceptive young man who, after their one night together, never returns her calls. Several weeks later Vasylysa, who lives with her mother, begins to feel unwell. Her mother immediately understands what has transpired and sends her daughter to the doctor. As the play’s narrator describes, “Lying on her back on the medical table, Vasylysa thought about Pavel and she felt like a fool” (Kavol’chuk and Kazlauskas Reference Kavol’chuk and Kazlauskas2018:5). Dressed in white, the young woman lies down on what had served as the kitchen table in the previous scene with her mother. Now as the setting for her medical examination, the table is lit up along the edges with bright fluorescent track lighting that provides a harsh and clinical atmosphere to the proceedings. With her feet up on the table and her knees spread wide, Vasylysa winces as the actor playing the doctor demonstratively and ominously pulls on his rubber gloves to begin his medical exam.

Figure 5. Avdiivs’kyi Romeo by Filip Kazlauskas and Evheniia Koval’chuk, directed by Pavlo Ar’e. From left: Vitalina Bibliv, Anna Kirsh, and Anatolii Marempol’s’kyi. Ukrainian Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music, Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

After returning home, Vasylysa shares her news with her mother:

VASYLYSA: I’m pregnant

(Silence)

NARRATOR: Everything was ruined before it had even begun.

(VASYLYSA goes to her room to think about what she should do)

MOTHER: An abortion?!? God forbid.

(VASYLYSA’s mother goes to her daughter)

VASYLYSA: Mom, I’m sorry I was so stupid. I thought it was true love, but…

MOTHER: (Interrupting) We’ll figure it out.

The striking image of a vulnerable young woman in white lying on her back for a medical examination, fluorescent track lighting framing her body, is echoed in another play from the same year, Tsina mrii (The Cost of a Dream). In this play, written by Karina Iablon’ska with Anastasiia Kutsova and Daryna Riashko, audience members follow the feminist awakening of a young woman named Sophia as she breaks away from the patriarchal expectations of her family in order to pursue her dream of starting her own business as a fashion designer. At the start of the play, the lights come up to reveal Sophia framed by the same type of fluorescent track lighting seen on the doctor’s table in Avdiivs’kyi Romeo, only this time the lighting appears in the shape of an open doorway. The actor who plays Sophia stands onstage framed by the fluorescent doorframe, holding a collection of wire hangers. She hangs one carefully from the frame and continues to balance them all, hanging each one precariously from the one that came before.

This image of Sophia’s wire coat hangers, in combination with the open door made of fluorescent track lighting, refers not only to the protagonist’s choices about whether or not to pursue her dream of becoming a fashion designer but also to the doctor’s examination table in Avdiivs’kyi Romeo. The arresting image also resonates with the broader historical movement for gender equality and reproductive rights. Echoing visual cues between plays is only one example of how the use of music, video, and design offered Class Act audience members a visual and aural map with which to appreciate each play in its own right while also building awareness of how the distinct voices of each text formed an essential part of a larger unified whole.

Figure 6. Tsina mrii (The Cost of a Dream) by Daryna Riashko, Anastasiia Kutsova, and Karina Iablons’ka, directed by Alik Sardarian. From left: Anna Kuzina, Alina Skoryk. Ukrainian Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music, Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

To stage each year’s plays together in this way, united by a common artistic vision, contributed to the sense of national unity and narrative coherence the project was built to foster. Each year’s production struck an intricate balance, prioritizing and respecting the individual narratives featured in each of the short plays while also highlighting their commonalities and thematic links through the overall aesthetic approach to performance. In this way, Class Act: East-West embodied an idealistic vision of Ukraine as a pluralistic society with the capacity to embrace its multicultural and multilingual history and to envision its own multiplicity as an emblem of strength rather than as a source of conflict.

Class Act created space for dialogue between teens from different parts of Ukraine and also served as a way for members of Ukraine’s creative community to develop their consciousness of and engagement with political art and theatre for social change. All of the theatre-makers who took part in the program had been active in the Euromaidan protests. As Class Act actor Katerina Vishneva says, theatre-makers in Ukraine “became more courageous” after Euromaidan as they recognized the need for a revolution within the theatre world as well as society as a whole (Espresso TV 2018). This element of the project was not lost on Class Act actor Roman Iasinovs’kyi, who spoke about precisely this question in a 2018 interview. A well-known actor in Ukraine who played a starring role in Vorozhbyt’s 2017 action film, Cyborgs: Heroes Never Die, Iasinovs’kyi participated in all three years of Class Act: East-West. Reflecting on what distinguished his experience as a performer in Class Act from his other work in theatre and film he says, “I read a lot of scripts these days. Some good, some not so good. What the kids write is always fresh […] I like working with the scripts of these kids. I like working in such a short amount of time for maximum creativity. It brings us all together” (Radio Hayat Reference Hayat2018). Iasinovs’kyi goes on to compare his experience performing in Class Act with his recent work performing in a production of Antigone, a major international collaboration between the Ukrainian Theatre Dakh and the French director Lucie Berelowitsch. He describes the show as a “big production, two hours long with no interval, expensive scenery” and recalls how “audiences arrive, they watch the show, they leave, and they forget about it” (Radio Hayat Reference Hayat2018).

Figure 7. Ubit’ slona (To Kill an Elephant) by Danylo Chuykov, directed by Maksym Holenko. From left: Maikl Shchur, Oleksiy Dorychevs’kyi, Roman Iasinovs’kyi. Ukrainian Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music, Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

Playwright Marina Smilianets served as a writing mentor in 2018 and points to a similar dynamic:

You listen to these kids and you understand that we adults have become used to thinking about things in a certain way. Whereas they approach the same topics in fresh and unexpected ways. Then you come to realize, it’s actually genius. […] On this project, we all discover something about ourselves, something that we never even imagined before. And it all happens thanks to the kids. (in Vasiura Reference Vasiura2018)

Class Act: East-West not only offered its teenage participants a sense of increased confidence and opportunity for social connection and cohesion, it also provided Ukraine’s professional artistic community a sense of purpose and the confidence to imagine a world in which theatre mattered.

“Don’t forget to turn off your television”

In one of the most memorable Class Act plays, a family of refugees is portrayed attempting to flee an unnamed authoritarian and war-torn country. Artem, a 17-year-old aspiring actor, negotiates with a border patrol bureaucrat to organize an escape route for himself, his mother, and his 6-year-old sister. Throughout the play, television and radio announcements are heard in the background describing the declining state of social welfare. In performance, these proclamations are voiced by well-known political satirist Maikl Shchur, whose head pops up from under the stage framed by an old-school television as he speaks into a newsroom style microphone: “Parliament has passed a law prohibiting minors from leaving the country”; “The Orthodox Church prays sincerely for our soldiers fighting in the south”; “Dear citizens, the age of retirement has now been raised to 75”; “Dear citizens, in connection to the rise of retirement age, the state now promises to pay for the funerals of all those who never live to see it” (Chuikov Reference Chuikov2018:1–4).

Figure 8. Ubit’ slona (To Kill an Elephant) by Danylo Chuykov, directed by Maksym Holenko. Featuring Oleksiy Dorychevs’kyi. Ukrainian Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music, Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

Upon learning that Artem is an actor, or rather hopes to become one, the border guard offers him a deal. The teenager is to pose as a performer in an upcoming production of Hamlet. At the end of the play, Artem must take out the pistol which will have been provided to him in advance and “kill the elephant.” Artem soon realizes that to “kill the elephant” is a euphemism for assassinating the president. Only then, the border guard asserts, will he arrange safe passage out of the country for Artem and his family. Soon thereafter, Artem is seen rehearsing Hamlet’s “To Be or Not to Be” soliloquy and discussing with his little sister Ania the task that has been assigned to him. “I’ll never get it, this is a bust,” he claims. “Yeah, killing someone is probably really difficult,” Ania responds. “No that’s not it at all,” Artem explains, “I’ve never actually acted before. I’m scared of speaking in front of an audience, especially an audience this big. There’s got to be at least 1,000 seats in this theatre.” He gestures towards the actual 1,000-seat audience in front of him. “I’m screwed,” he concludes. Ania comforts her brother, “Tema, let’s keep rehearsing. Now’s not the time to give up” (3–4).

The day in question has arrived; Artem has played his role as an actor and is confronted by the president who is played by an actor with a booming voice and an old television for a head. The president congratulates Artem on his performance. The boy realizes in the moment that he cannot assassinate the president. He takes the pistol out, lays it on the table, and informs the television-headed president that there are people in his circle who wish him dead. Just then the border guard rushes in, takes up the pistol, and shoots the president himself. The words “Kill the elephant, kill the elephant” flash on the screen behind them, contributing to an atmosphere of lethal chaos. The broadcaster’s head reappears in the old television downstage as he speaks into the microphone, “kill the elephant, kill the elephant.” Artem watches as the guard begins to turn the pistol towards him before suddenly and inexplicably pointing the gun at himself and pulling the trigger. Artem cowers in the corner in shock as the television announcer sings out “Now you are the president!” pointing to Artem. The president has resigned and a new one has already been elected. Under this new regime society returns to the time of feudalism. “Yes! You are the president!” (5). Shaking amidst the cries of the broadcaster and the flashing of screens all around him, Artem stands up, retrieves the pistol, and decisively empties the last clip into the television. The lights go out. On a large screen center stage, a projection reads “Don’t forget to turn off your television.”

A disturbing exploration of violence, media, and individual agency in contemporary culture, this 10-minute play entitled Ubit’ slona (To Kill an Elephant) was written by 15-year-old Danylo Chuikov from the eastern city of Avdiivka and directed by Maksym Holenko, one of Ukraine’s most revered theatre directors. The play portrays the experience of an individual faced with the task of making an impossible choice to protect his family. In the process he must come to terms with the influence of mass media in our digital world. These themes are relevant to global audiences but were especially urgent to Ukrainians who were, at that time, being targeted by the Kremlin’s misinformation campaign that sought to deepen divisions and encourage discord between people from different parts of the country. Ubit’ slona is yet another example of how the Class Act: East-West plays consistently offered unusual insights and arresting interpretations of the historical and cultural moment in which they were created and generated exceptionally evocative theatre.

Figure 9. Ubit’ slona (To Kill an Elephant) by Danylo Chuykov, directed by Maksym Holenko. From left: Oleksiy Dorychevs’kyi, Oleh Prymohenov. Ukrainian Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music, Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

Many of the theatre-makers who served as directors and writing mentors for Class Act have gone on to initiate and participate in key projects explicitly built to foster a vibrant culture of new drama in the country. Since the final Class Act: East-West performance in 2018, several follow-on projects have emerged. Director Vlada Belozorenko curated a collection of five Class Act plays, which were staged together at the Actor’s Theatre in Kyiv in September 2019 and were restaged and streamed live in June 2020 during the early months of the Covid pandemic in an effort to bring online audiences a sense of community and purpose during a time of global isolation and uncertainty.

Class Act creator Natalka Vorozhbyt has garnered increased international recognition with her directorial debut of the film Bad Roads about the war in Donbas, which was adapted from her 2017 play of the same title. In addition to premiering at the 35th Venice International Film Critics’ Week in 2020, the film was selected as the Ukrainian entry for the Best International Feature Film at the 94th Academy Awards.

Another example is playwright Iryna Harets, who served as a Class Act mentor in 2016 and later created an open-source online archive for Ukrainian playwriting called UKRDRAMAHUB. Footnote 13 Featuring select works from over 75 of Ukraine’s leading playwrights, this completely free website allows users to search the texts by topic, title, author, and genre. The Facebook group associated with the project quickly became an important center for information about playwriting initiatives and opportunities across the country, and also a forum for discussion about the development of Ukrainian drama and performance more broadly. The team behind UKRDRAMAHUB also organized a country-wide playwriting competition in 2021 and produced a series of online events featuring presentations from and conversations between the country’s most innovative and socially engaged theatre-makers.Footnote 14

Figure 10. Audience members gather in front of the theatre before a Class Act: East-West performance. Ukrainian Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music, Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

Together with playwright Lena Lagushankova, playwright Liudmyla Tymoshenko (a Class Act mentor from 2017) organized a series of four of playwriting competitions specifically for female playwrights called the Love and Beaver Festival. Held at various venues around Kyiv, this initiative staged readings of plays by female playwrights including one version in which all of the texts read were by writers who had never before been produced, some of whom had never before written a play. The project supported a new generation of writers who were able to see their plays read onstage by theatre professionals and receive immediate feedback from the broader theatre community.

Perhaps most notable in terms of building an active community of Ukrainian playwrights during these years has been the 2020 founding of the country’s first democratically run playwright-led theatre collective, the Theatre of Playwrights. Led by writer Maksym Kurochkin, the group is made up of 20 leading Ukrainian playwrights, including Natalka Vorozhbyt and many other writers who served as mentors for the Class Act: East-West project: Pavlo Ar’e, Nataliia Blok, Andriy Bondarenko, Iryna Harets, Anastasiia Kosodii, Olha Matsiupa, and Liudmyla Tymoshenko. After more than a year of community organizing, fundraising, and renovations, the Theatre of Playwrights opened its doors in Kyiv in December 2021. The project’s founders built upon years of grassroots initiatives, such as those described above, and created the conditions for Ukrainian theatre-makers, playwrights in particular, to establish new languages of solidarity, multiplicity, and self-definition.

Three months after the opening of the Theatre of Playwrights however, the group was forced to temporarily close its Kyiv venue because of the war. In February 2022 Ukrainian theatres across the country were swiftly converted into shelters for internally displaced people. The state theatres, traditionally larger buildings with basements, have been used as bomb shelters just as every basement has been in Ukraine since the start of the invasion. Like many important cultural institutions in Ukraine, these historic buildings have also come under Russian attack in recent months, as in the case of the Mariupol Drama Theatre that was targeted and shelled on 16 March 2022, a tragedy that led to the deaths of over 300 Ukrainian civilians who had been sheltering in the building, including dozens of children (BBC 2022).

Figure 11. Student playwrights and Class Act: East-West volunteers on the bank of the Dnipro River in Kyiv, 2018. (Photo by Anastasiia Vlasova)

Since the end of February 2022, many of the professional writers, actors, and directors who participated in Class Act have fled the war primarily to Poland, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria where they are organizing and fundraising for humanitarian initiatives from abroad. Others have remained in the country and are working to support the remarkable grassroots resistance against Russian aggression that has been the focus of so much international media coverage. More than a few Class Act actors, directors, and playwrights have taken up arms and joined the military or the territorial defense units.

At the time of writing, the horror of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine is heading into its fourth month. However, the war and Russia’s occupation of Ukrainian territory is now in its eighth year. Since their participation in Class Act: East-West, the teenagers who wrote plays for the project have grown up with the constant spectre of war on their doorstep. The eastern cities of Popasna and Avdiivka, where many of the Class Act students are from, were among the cities hardest hit in the early years of the war and have come under heavy shelling from the Russian military particularly since the consolidation of Russian troops in Donbas in April and May 2022. Some of the students had already moved away to other cities in Ukraine to work or to study, but many of them stayed and together with their families are facing the reality of this war as it engulfs their hometowns, again.

Given the current extreme circumstances of Ukraine’s creative community, it is impossible to say what will come of the new artistic languages created through programs like Class Act. The hope, the activism, and the optimism of those years is, in some senses, overshadowed now by the terror of Ukraine’s current reality as the country and its people continue to fight tirelessly for their right to exist.

As Ukrainian writer and scholar Sasha Dovzhyk describes:

For the past eight years, the Maidan generation was fighting in Europe’s forgotten war […] While much of the world appeared preoccupied with appeasing Putin, Ukrainians were busy defending their country against his army. Unlike the West that sleepwalked into this disaster, Ukrainians were prepared to resist. Indeed, Ukraine’s fierce resistance to Russia’s invasion surprised many in the West. The Kremlin anticipated Ukraine to be defeated in a matter of days, and Western pundits largely agreed […] The readiness which I witnessed in Ukraine during the first weeks of Russia’s war was both startling, because of its sheer pervasiveness and force, and unsurprising, because of its rootedness in the national tradition of anticolonial resistance. (Dovzhyk Reference Dovzhyk2022)

Dovzhyk is referring to the ethos of resistance and resilience embedded in centuries of Ukrainian literature. Nonetheless, it seems to me that the continued work of finding a language for articulating one’s story and calling it one’s own is today as essential to Ukraine’s anticolonial resistance as it was in the periods that Dovzhyk is discussing. The capacity to find a common language across cultural divisions and to comprehend the significance of how stories and histories are told is crucial to Ukraine’s ongoing fight for political sovereignty and self-definition. And, in that political, cultural, and historical context, a seemingly straightforward youth theatre project like Class Act: East-West is revealed to be nothing short of revolutionary.