Shabih’khani and Shabih’gardans

Scholars studying traditional Persian arts often do not conduct in‐depth research on historical documents written in Persian.Footnote 1

Many research efforts focused on these artistic traditions have been limited to non‐Persian sources and observations, adding little to previous knowledge. Such is the case of studies of shabih’khaniFootnote 2

(![]() ), also widely known as ta’ziyeh

), also widely known as ta’ziyeh ![]() . Shabih’khani, one of several traditional theatre forms of Shi’a Islam, is a popular indigenous Iranian theatrical form. The earliest accounts of shabih’khani date from the 18th century, but the performance must certainly have developed centuries earlier, long before there was Iranian contact with Western theatre. It is therefore fully indigenous. Shabih’khani evolved into an elaborate and popular theatrical tradition on its own.Footnote 3

. Shabih’khani, one of several traditional theatre forms of Shi’a Islam, is a popular indigenous Iranian theatrical form. The earliest accounts of shabih’khani date from the 18th century, but the performance must certainly have developed centuries earlier, long before there was Iranian contact with Western theatre. It is therefore fully indigenous. Shabih’khani evolved into an elaborate and popular theatrical tradition on its own.Footnote 3

The theatrical conventions of shabih’khani are not entirely unique. It is staged in the round and uses animals as well as human actors, but it is a fully realized drama, not circus. The actors — called shabih’khans ![]() , performers of shabih’ (شبیه), which might be translated as “simulation,” “mimesis,” “verisimilitude,” or “imitation” — perform holding in their hands individual character sides called tumar (طومار) or fard (فرد) in order to distance themselves from the roles they are portraying. This separation is necessary to protect performers from religious conservatives who may accuse the actors of engaging in idolatry by portraying human figures.Footnote 4

Characters both declaim their lines and chant them using traditional virtuosic classical Persian musical modes.Footnote 5

The scripts are highly literary, replete with Persian poetic structures. Each majles (مجلس), or play,Footnote 6

is quite flexible: performances expand or contract based on time, occasion, venue, and audience reaction. These edits on the fly are built into the performance practice; they are anticipated by performers and by the director, the shabih’gardan.Footnote 7

There are no sets; the performance unfolds on a bare platform. The actors are elaborately costumed and use many props. They are exclusively male, with men taking women’s roles, except when female shabi’khani is being performed. Young boys play children, both male and female. In these ways, shabih’khani conforms to the performance conventions of other traditional Iranian theatre forms.Footnote 8

Casts are flexible in size: elaborate productions may have hundreds, modest productions only a dozen or so. This flexibility in all dimensions of the performance explains the need for an astute and authoritative shabih’gardan.

, performers of shabih’ (شبیه), which might be translated as “simulation,” “mimesis,” “verisimilitude,” or “imitation” — perform holding in their hands individual character sides called tumar (طومار) or fard (فرد) in order to distance themselves from the roles they are portraying. This separation is necessary to protect performers from religious conservatives who may accuse the actors of engaging in idolatry by portraying human figures.Footnote 4

Characters both declaim their lines and chant them using traditional virtuosic classical Persian musical modes.Footnote 5

The scripts are highly literary, replete with Persian poetic structures. Each majles (مجلس), or play,Footnote 6

is quite flexible: performances expand or contract based on time, occasion, venue, and audience reaction. These edits on the fly are built into the performance practice; they are anticipated by performers and by the director, the shabih’gardan.Footnote 7

There are no sets; the performance unfolds on a bare platform. The actors are elaborately costumed and use many props. They are exclusively male, with men taking women’s roles, except when female shabi’khani is being performed. Young boys play children, both male and female. In these ways, shabih’khani conforms to the performance conventions of other traditional Iranian theatre forms.Footnote 8

Casts are flexible in size: elaborate productions may have hundreds, modest productions only a dozen or so. This flexibility in all dimensions of the performance explains the need for an astute and authoritative shabih’gardan.

Information on shabih’khani including eyewitnesses, scripts, and other contemporary texts has been limited, incomplete, or wrong. Mistaken interpretations of these materials have often been replicated from one publication to another as scholars repeat past mistakes.Footnote 9 Additionally, because performances of shabih’khani in modern times have focused on the martyrdom of the prophet Mohammad’s (حضرت محمد) grandson, Imam Hussein (امام حسین), which took place in Karbala(کربلا) in current‐day Iraq in 680 CE/59 SH/61 AH,Footnote 10 there has been a tendency for scholars to treat the performance as a religious ritual, ignoring its clear identity as a theatrical performance. However, shabih’khani was always explicitly theatrical, whatever its themes and content. It has been especially difficult to piece together the evolution of shabih’khani during the Qajar era (عصر قاجار) (1789 to 1925 CE/1168 to 1304 SH). The bulk of contemporary academic papers are based on personal memories and observations from the 20th century.Footnote 11

We rely instead on newly discovered, verified historical documents, most of which previously have not been accessible to scholars.Footnote 12

These materials are archived in the Library, Museum, and Document Center of the Iranian parliament (LMDCIP) ![]() . In addition, we have had access to, and have based our study on performance texts from, the Malek National Library and Museum of Iran

. In addition, we have had access to, and have based our study on performance texts from, the Malek National Library and Museum of Iran ![]() and private collections. These new documents demonstrate the emergence of professional shabih’khani directors and dramaturgs in Iran during the rule of Naser al‐Din Shah Qajar (Reference Amanat1831–1896 CE/1209–1275 SH), here referred to as the Naseri period

and private collections. These new documents demonstrate the emergence of professional shabih’khani directors and dramaturgs in Iran during the rule of Naser al‐Din Shah Qajar (Reference Amanat1831–1896 CE/1209–1275 SH), here referred to as the Naseri period ![]() (1848–1896 CE/1227–1275 SH). Our findings allow us to evaluate shabih’khani as something more than a traditional religious ritual expression. In fact, the shabih’khani tradition institutionalizes the role of the theatre director and the functions of the dramaturg prior to the emergence of such roles in Europe. We have uncovered evidence of these professions in Iran as early as the late 18th century.

(1848–1896 CE/1227–1275 SH). Our findings allow us to evaluate shabih’khani as something more than a traditional religious ritual expression. In fact, the shabih’khani tradition institutionalizes the role of the theatre director and the functions of the dramaturg prior to the emergence of such roles in Europe. We have uncovered evidence of these professions in Iran as early as the late 18th century.

The aforementioned newly discovered texts, including records of performances, manuscripts, annotations, and stage directions, center on the work of two renowned shabih’gardans — Mirza Mohammad Taqi Ta’ziyehgardan ![]() (?–1872 CE/1250 SH) and Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka

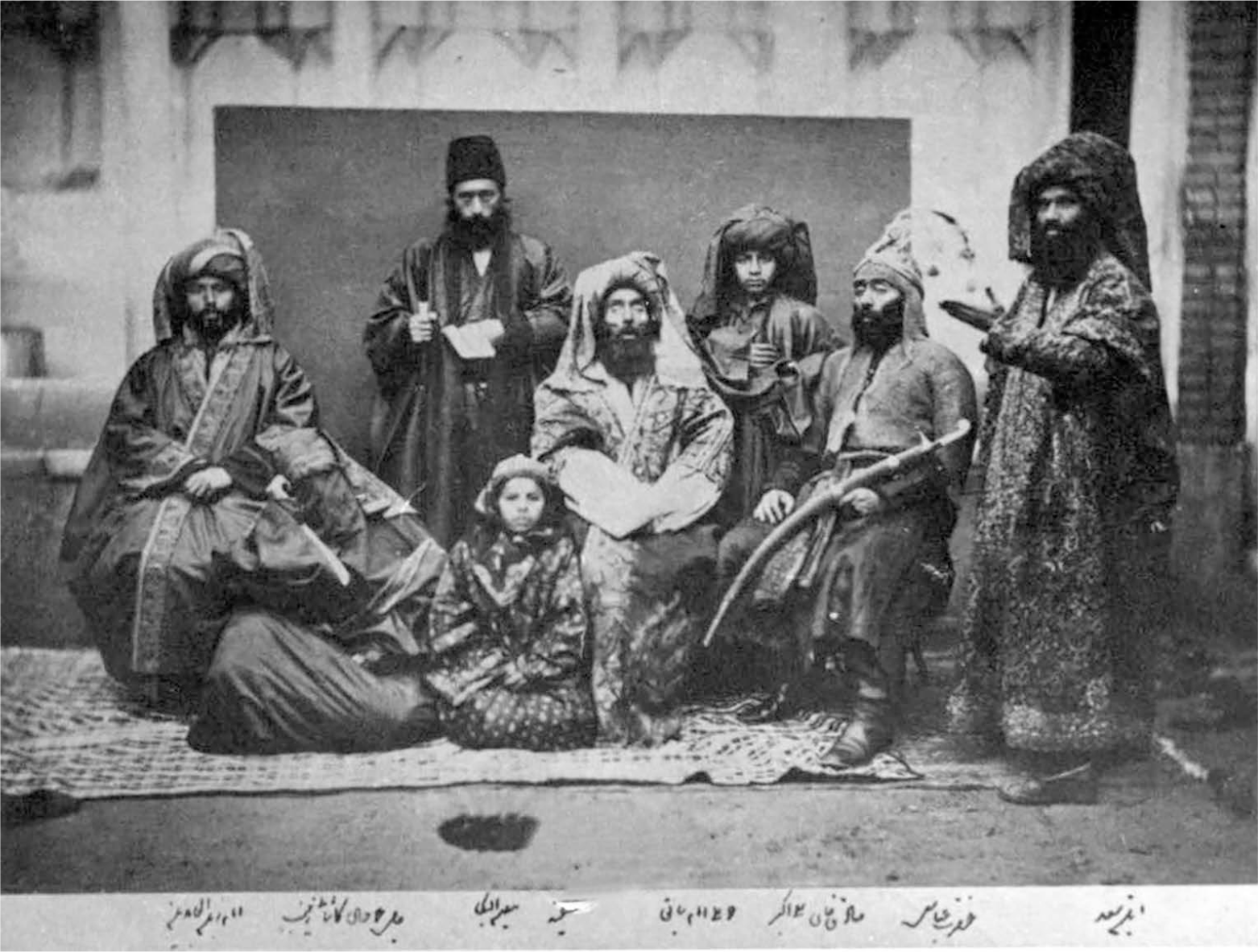

(?–1872 CE/1250 SH) and Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka ![]() (?–1914 CE/1293 SH; see fig. 1). “Mirza” means amanuensis or scribe. “Mo’in‐ol‐Boka” is a salaried court title meaning “Master of Weeping or Mourning.” These two artists, and especially Mohammad Bagher, are the basis for this study.

(?–1914 CE/1293 SH; see fig. 1). “Mirza” means amanuensis or scribe. “Mo’in‐ol‐Boka” is a salaried court title meaning “Master of Weeping or Mourning.” These two artists, and especially Mohammad Bagher, are the basis for this study.

Figure 1. Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka with his manuscripts among actors in costume. (Photo courtesy of Central Library of University of Tehran, 7th Album, Number 235)

Much contemporary scholarship on shabih’khani describes the work of a shabih’gardan as a kind of stage manager. In reality, the shabih’gardan is a director and shabih’nevis (شبیهنویس) is a Persian term for an author of a shabih’khani. The word “nevis” indicates a writer. There are no words for a dramaturg, but Mohammad Bagher can be considered a dramaturg in the contemporary sense of the term. Consequently, we will use the terms “director” and “dramaturg” for Mohammad Bagher, depending on the context.

From Shabih’ to Shabih’khani

Peter Chelkowski, one of the most widely cited scholars of shabih’khani/ta’ziyeh, writes:

The first recorded public mourning ceremonies for Hussein took place in Baghdad in the fourth Islamic century. Sultan Muizz ad‐Dawla of the Shiite Buyid dynasty ordered the markets closed on the day of Ashura, Muharram 10th, in the year 352 of the Muslim calendar (963 CE). Processions of Shiites circled the city while weeping, wailing and striking their heads in grief. The women were disheveled, and everyone wore torn black clothing. Hussein’s murderers were soundly cursed. The Sunnis reacted with processions of their own in which Ali was denigrated for his defeat at the battle of “the Camel.” This was re‐enacted in the streets of Baghdad by costumed characters mounted on camels and horses. Bloody riots between the participants of these two opposing processions were recorded by historians even after the Shia Buyids. (Reference Chelkowski1985:20)Footnote 13

Chelkowski’s account outlines the first steps in the development of public commemorations of the events of Karbala, namely, the emergence of the first processional performance of an Islamic historical event, paradoxically, enacted by Sunni Muslims rather than Shi’as. Chelkowski drew on the accounts of Mayel Baktash (Baktash Reference Baktash1969; see also Baktash Reference Baktash and Chelkowski1979) and the historians Ali Ibn Al‐Athir and Abu’l‐Fedā EsmāI’l Ibn Kathir, who wrote “the Sunni Muslims, in commemoration of the Battle of the Camel (جنگ جمل) and the defeat of Imam Ali (امام علی), launched a procession with characters dressed as the historical Sunni Islamic personages Aisha, Talhah, and Zubayr[ Footnote 14 ] (شبیه عایشه، طلحه و زبیر) riding on camels” (Ibn Al‐Athir Reference Ibn Al-Athir1972:44; see also Ibn Kathir 1988:312).

We can refer to these first processions as shabih’. From this point, these commemorative processions continued to evolve, eventually becoming a complete complex performance, shabih’khani or ta’ziyeh (تعزیه).Footnote 15

The oldest known document reporting a full instance of a processional shabih’ depicting the Shi’a account of the martyrdom of Imam Hussein is found in the German book Die Heutige Historie und Geographie (History and Geography Today) by Thomas Salmon and Matthias van Goch (Reference Salmon and van Goch1739), three years after the end of the Safavid dynasty (صفوی) (1501–1736 CE/880–1114 SH) and at the start of the Afsharid dynasty (افشاریان) (1736–1796 CE/1114 –1175 SH) (Salmon and van Goch Reference Salmon and van Goch1739:252). Salmon and van Goch report that this dialogueless processional shabih’ had a greater number of theatrical elements than the one Ibn Al‐Athir reported as the first shabih’. During the 766‐year gap in records, we must assume that shabih’ evolved from early dialogueless processions and visual tableaux of the events of Ashura (عاشورا) into fully theatrically realized shabih’khani. In its 18th‐century rudimentary stage, as noted above, shabih’ was a reenactment of the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, his family, and his followers in the battle of Karbala during the Islamic lunar month of Muharram, 680 CE. The battle and martyrdom were reenacted with the two sides — the martyrs and their attackers — visually differentiated by established signs and symbols. As Farokh Gaffary notes: “This must be the last stage of the lengthy evolution of a ritual before it becomes verbal and takes dramatic form” (Reference Gaffary1984:367).

“The Muharram ceremonies were flourishing and developing under the Safavid rule” (1501–1736 CE/880–1114 SH) (Chelkowski Reference Chelkowski1977:33), the first Iranian dynasty with Shi’ism as the official religion. Safavid officials supported Shi’ite mourning processions and encouraged the development of this new form of performative expression to advance their political goals and bolster their legitimacy (Aghaie Reference Aghaie2004:12).

A full theatrical shabih’khani performance took place on Kharq Island (جزیره خارک) in the Persian Gulf in 1765 as described by Carsten Niebuhr, a German cartographer and explorer accompanying the 1761 to 1767 Royal Danish Arabia Expedition (Niebuhr Reference Niebuhr1778:199–200). Niebuhr witnessed the dramatic depiction of the martyrdom of Imam Hussein and his followers in what appears to be a fundamental majles that would evolve into the extensive body of complete separate dramas depicting individual episodes of the Karbala siege, battles, and martyrdoms.Footnote 16

Twenty‐two years after Niebuhr, in 1787, English orientalist and army officer William Francklin gave a full description of shabih’khani, including a scene where Imam Hussein’s followers attempt to get water from the Euphrates River, triggering a battle. This majles included a detailed depiction of the marriage of Qassem (قاسم), Imam Hussein’s nephew, and Qassem’s martyrdom (Francklin Reference Francklin1790:249).

In the interval between Niebuhr’s and Francklin’s accounts, we can see how much the dramatic scope of the depiction of the events of Karbala had developed. The inclusion of the marriage and martyrdom of Qassem (Gobineau Reference Gobineau1866b)Footnote 17 is evidence of major additions to the stories performed in shabih’khani. While the main protagonist is always Imam Hussein, other characters became so important that even a peripheral figure like Qassem became the protagonist of a full shabih’khani majles.Footnote 18 Based on secondary characters, many episodes of the Imam Hussein martyrdom saga were written as full‐length majleses, with titles such as: A’roosi Qassem (عروسی قاسم, Qassem’s Marriage), Khoruj‐e‐Mokhtar (خروج مختار, Mokhtar’s Exit), Za’n‐e‐Nasrani (زن نصرانی, Nasrani’s Wife), and many others. After this time period, shabih’khani was performed outside present‐day Iran in Shi’a communities in Azerbaijan, Lebanon, Iraq, Bahrain, and elsewhere (Aghaie Reference Aghaie2004; Jaffri Reference Jaffri and Chelkowski1979; Mervin Reference Mervin, Puig and Mermier2007; Riggio Reference Riggio1994). Although the complete timeline of the transformation from “processional” or “tableau” shabih’ to shabih’khani is not entirely clear (the time span is vast, from 973 to 1787 CE), it is definite that the theatrical tradition underwent an 817‐year‐evolution from processions, depictions, and mimicry to elaborate theatrical performances. This development accelerated immediately after the end of Safavid rule and “reached its peak during the Qajar period thanks, in particular, to the great interest and patronage shown by the Qajar Kings” (Anvar Reference Anvar2005:61; see also Calmard Reference Calmard1974, Reference Calmard and Chelkowski1979).

Shabih’khani became an institutionalized feature of cultural life during the Qajar period, replete with professional artists who introduced innovations. Gradually, accounts of shabih’khani are found in the early scholarly work of Europeans, a limited number of eyewitness descriptions and collections of scripts (Gobineau Reference Gobineau1866c; Arnold Reference Arnold1871; Chodźko Reference Chodźko1878; Pelly Reference Pelly1879; Lassy Reference Lassy1916; Krymsky Reference Krymsky1925; Litten Reference Litten1929). The annotations and stage directions found in the documents we analyzed provide more valuable information about the innovations and the performance practices of shabih’khani. Annotated shabih’namehs Footnote 19 (the scripts of shabih’khani) and other documents from the Qajar era provide much detailed information about these performance practices, making possible a historical analysis of the transformation and development of shabih’khani.

Shabih’namehs of the Qajar Era

Most traditional Iranian performance genres rely heavily on improvisation; for example, ruhozi (روحوضی) is a comic tradition without any written scripts (Beeman Reference Beeman, Bonine and Keddie1981a, Reference Beeman1981b, Reference Beeman1982, Reference Beeman2011; Floor Reference Floor2005; Gaffary Reference Gaffary1984:372). Shabih’khani is the sole traditional Iranian theatre form that relies on written texts, while retaining the same flexibility to expand or contract found in other Iranian performances.

A large number of Qajar shabih’namehs produced during the reign of Fath‐Ali Shah Qajar (جکومت فتحعلیشاه قاجار) (1772–1834 CE/1150–1213 SH) and subsequent rulers indicate a gradual transformation in line with the sociopolitical changes of the time. By studying extant manuscripts and tracing changes over time, one can gain insight into the minds of the creators of the Qajar era as shabih’khani evolved. Some developments included expanding existing stories, adding new stories, enhancing the roles of villains and antagonists — maokhalefkhans (مخالفخوان) in Persian — and streamlining for dramatic effect the dialogue of all characters. Most importantly, the evolution embodied a shift from a mournful, lamenting tone to a more heroic and epic representation of the stories.

Although a robust local printing industry began in the Safavid dynasty, printing spread more during the Naseri period (Afshar Reference Afshar1966:29). Publishing new books and republishing old ones such as Rawzat al–shuhada (روضة الشهدا, Garden of Martyrs)Footnote 20 motivated shabih’gardans to increase people’s awareness of the martyrs’ saga, especially the culminating events of Ashura — the climactic day when Imam Hussein was martyred. Because most people were illiterate during this period, it was the performance of mourning rituals based on the new books and carried out by literate religious officials and eulogists that encouraged religious devotion.

Sociopolitical developments of the Naseri era also resulted in innovations among shabih’nevises and shabih’gardans, leading them to create better, well‐composed shabih’khani performances.Footnote 21 The influence of the Qajar rulers cannot be understated. As patrons they provided financial support and a more positive outlook towards the arts in general.Footnote 22 During the Naseri era, shabih’khani, which had previously been considered an avocation or a part‐time occupation, became a much‐respected profession. Financial evidence from documents of this period shows this transformation. In 1886 CE/1265 SH, the income of Mohammad Bagher and other shabih’gardans working in the Royal Theatre, the Tekyeh Dowlat (تکیه دولت),Footnote 23 grew from a perfunctory monetary tip from the court into a full living wage (see fig. 1 in SM).Footnote 24

There are several published collections of early shabih’namehs. These include the collection of Aleksander Chodźko, Théatre persan: choix de téaziés ou drames (manuscripts were purchased in 1833; Chodźko Reference Chodźko1878); the collection of Wilhelm Litten, Das Drama in Persien (manuscripts dating from 1831 to 1834; Litten Reference Litten1929); the collection of the Malek National Museum and Library of Iran (Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2013); and the collection of Lewis Pelly (transcripts of performances from 1862 to 1873; Pelly Reference Pelly1879). Of special importance is the extensive 1,055‐volume shabih’khani collection of Enrico Cerulli acquired while he was the Italian ambassador to Iran from 1950 to 1954 and deposited in the Vatican Library (Cerulli Reference Cerulli1954, Reference Cerulli1971a, Reference Cerulli1971b, Reference Cerulli1971c; Rossi and Bombaci Reference Rossi and Bombaci1961). The oldest majles from these collections was written in 1829 (Malik’pūr Reference Malik’pūr2004:130–37). An inspection of these materials shows the clear evolution of the Iranian shabih’khani throughout the Qajar period.

Apart from these collections of shabih’khani manuscripts by Europeans, the newly discovered collections in the aforementioned Library, Museum, and Document Center of the Iranian Parliament (LMDCIP), retrieved and catalogued in 2010,Footnote 25 give a better understanding of the Qajar shabih’namehs. The LMDCIP documents, written between 1831 CE/1210 SH and the beginning of the Pahlavi era (پهلوی) (1925–1979 CE/1304 –1357 SH), expand our knowledge of the texts of two prominent shabih’gardans and shabih’nevises in the Naseri period: Mirza Mohammad Taqi Ta’ziyehgardan (?–1872 CE/1250 SH) and Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka (?–1914 CE/1293 SH) (Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2011). The relationship of these two shabih’gardans to each other and details of their lives and the workings of the Iranian theatre of that time have been, until now, shrouded in mystery.

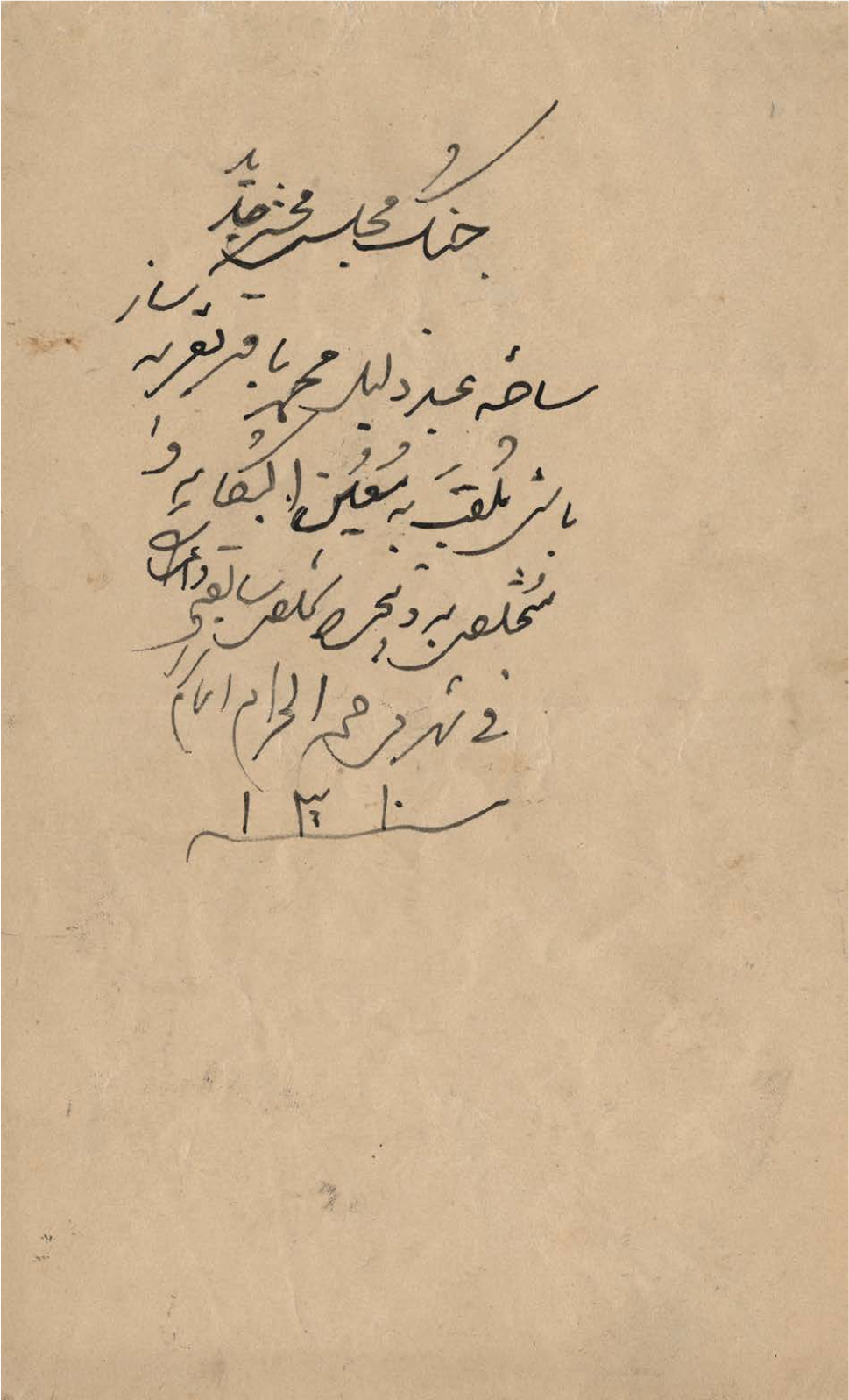

Bahram Beyzai (بهرام بیضایی), in his well‐known work Namayesh dar Iran (نمایش درایران, Theatre in Iran), writes, “Maqtalnevises [مقتلنویس, another term for shabih’nevis] never signed their texts, seeking divine rewards and not material ones” (1965:134).Footnote 26 But the newly revealed documents, in LMDCIP and in other locations, reveal that a vast number of shabih’namehs include authors’ names or pseudonyms incorporated in the verses. Therefore, it is wrong to assume that shabih’ authors, in any time or position, did not sign their work. Indeed, the findings of the present study are based on annotations left by the authors (see fig. 2).

Figure 2. Author’s name or pseudonym on four shabih’namehs. (Photo assemblage by Reza Kouchek‐zadeh and Milad Azarm; photos courtesy of the LMDCIP archive)

Apart from documenting contextual and structural changes from early shabih’namehs to more recent ones, our aim is to detect directorial and dramaturgical elements found in the LMDCIP documents used in performances: The sides, or tumar, held by performers during performances; fully compiled shabih’nameh scripts, called jong (جنگ); and handwritten annotations indicating stage directions found on both kinds of documents. None of the older published collections mentioned earlier contain such annotations. These publications give only the names of characters and the dialogue in verse. But clearly, as the LMDCIP documents show, shabih’khani underwent a gradual transformation with director’s notes and stage directions appearing alongside the dialogue. These notes show the theatrical knowledge of the shabih’gardans. For instance, signs of directing and dramaturgy can be seen in manuscripts 20411, 20383, 20347, 20279, 20213Footnote 27 (see fig. 2 in SM). These are only a few examples out of hundreds.

Manuscript number 20324, majles Mahshar (محشر The Day of Judgment), for example, is one shabih’nameh draft (see fig. 3 in SM). It exists both in this draft form and in a polished rewritten final copy, both of which are archived in the LMDCIP collection. As mentioned, shabih’nameh documents, produced before those in the LMDCIP collection, show no editing, director’s, or dramaturg’s notes.

Figure 3. Mirza Mohammad Bagher’s side note on the text of Mahshar ( محشر جدید , The Day of Judgment). (Photo courtesy of the LMDCIP archive)

Thus, though previously known primarily as authors of “mournful verse,” the shabih’nevises gradually evolved into playwrights. Additionally, they evolved from being managers of shabih’khani troupes to well‐informed professional stage directors. This creates a stark contrast to what has long been thought to have been their low‐level managerial activities. Previously, shabih’nevises and shabih’gardans were considered devoted semiliterate producers of religious pageants rather than masters of deep theatrical knowledge. In this respect, Beyzai writes, “The poet — maqtalnevis — is not an expert or a scholar. He only conveys his feelings” (Reference Beyzai1965:131). However, the collection at the LMDCIP shows authors with sophisticated technical and artistic knowledge of theatre. The directors’ notes in the LMDCIP collection are mainly written by Mirza Mohammad Taqi and Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka. Who were these artists?

Mirza Mohammad Taqi

Mirza Mohammad Taqi, the renowned shabih’gardan of Tehran, was raised to prominence during the reign of Mohammad Shah Qajar (محمدشاه قاجار) (1808–1848 CE/1186–1227 SH) and in the early years of the Naseri era. His birthplace is believed to have been Isfahan, but he moved to Tehran to pursue shabih’khani as a profession (Shahidi and Bulookbashi Reference Shahidi and Bulookbashi2001:710). He was the major shabih’gardan of Tekyeh Abbasabad (تکیه عباس آباد), the old Tekyeh Dowlat, or Tekyeh Haj Mirza Aghasi (تکیه حاج میرزا آقاسی) as well as other famous tekyehs in Tehran. Old Tekyeh Dowlat, Tekyeh Abbasabad, and Tekyeh Haj Mirza Aghasi are different names for one place called the Royal Tekyeh, several years before the new Tekyeh Dowlat was built in 1868 CE/1247 SH (Amanat Reference Amanat1997:435). The new Tekyeh Dowlat was destroyed in 1947 CE/1326 SH. The end of the Tekyeh Dowlat is well known, but there are many debates about the date of its inauguration. Based on the most recent book Memari Tekyeh Dowlat (معماری تکیه دولت, Architecture of Tekyeh Dowlat; 2018) by Eskandar Mokhtari, professor of architecture at the Islamic Azad University of Tehran, Tekyeh Dowlat was constructed gradually, completed in 1879 CE/1258 SH. Basing his conclusions on Etemad al–Saltanah’s notes, old maps of Tehran, and Sharaf Monthly (ماهنامه شرف), published during the Qajar era, Mokhtari finds that Tekyeh Dowlat’s construction began in 1868. According to Sharaf Monthly, it was finished four to five years later (Etemad al‐Saltanah Reference al-Saltanah and Khan1887), which means it opened in 1872 or 1873. Under the supervision of Bagher Ayatollahzadeh Shirazi (1936–2007), a famous architect and professor in Iran, a group excavated Tekyeh Dowlat’s site near Golestan Palace in 1995. They found mosaics, one of which was dated 1879. Thus, work on Tekyeh Dowlat began in 1868, it was inaugurated around 1873, and its ornamentations were finished in 1879.Footnote 28

Mohammad Taqi, who passed away in 1872, a year before the opening of the new Tekyeh Dowlat, is often referred to as a shabih’gardan or ta’ziyeh’gardan. However, in the LMDCIP collection, Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka, the younger shabih’gardan, refers to Taqi as a “master”: “the great Mo’in” or “the late Mo’in‐ol‐Boka.” Mohammad Bagher’s high regard for Mohammad Taqi is reflected in referring to him this way, as seen in texts 20111, 20172, 20183, etc. But none of the texts authored by Mohammad Taqi were signed with this honorific.

Abdullah Mostofi (عبدالله مستوفی) (1876–1950 CE/1255–1329 SH), who witnessed many shabih’khani performances at the Tekyeh Dowlat, writes, “Mirza Mohammad Taqi arranged performances and by expanding their storylines, transformed ta’ziyeh from a performance for the masses to one worthy of the royals. […] Anywhere he found a talented person, Mirza would follow him, and by force or promise, prepared that person for shabih’khani” ([1947] 1981:290). Enayatullah Shahidi (عنایت الله شهیدی) and Ali Bulookbashi (علی بلوکباشی) also characterize Mirza Mohammad Taqi’s dramaturgical work as editing verses into polished stage dialogue, incorporating renowned poems by Moghbel‐e‐sfahani (مقبل اصفهانی), Bidel‐e‐hirazi (بیدل شیرازی), and Shahab Isfahani (شهاب اصفهانی), and supporting authors of new shabihs with new stories (2001: 711). Mostofi further describes Mirza Mohammad Taqi’s contributions:

This tragic opera [shabih’khani] also had a regisseur who acted as an orchestra conductor. He determined the clothes for each role. His other duty was to do preparation and arrange the mise‐en‐scène as was common with Europeans. […He] educated the actors, teaching them proper gestures for each role, in order to make the performances appropriate for the king, which was one of his most arduous tasks. ([1947] Reference Mostofi1981:291)

Several LMDCIP manuscripts were composed or edited by Mohammad Taqi. “Asrari” (اسراری), the pseudonym associated with him by Shahidi and Bulookbashi, is inaccurate. In a large number of verses written by Mohammad Taqi as well as in his dramaturgical work, he referred to himself as “Fadayi” (فدایی).Footnote 29 Shahidi and Bulookbashi mistakenly attribute the title of Fadayi to Mohammad Bagher, Mohammad Taqi’s successor, but “Zabihi” (ذبیحی) is the correct pseudonym for Mohammad Bagher. His annotation on the margin of the text Mahshar (محشر, The Day of Judgment), manuscript 20436, clearly reads, “Composed by humble servant, Mohammad Bagher Ta’ziyehsaz‐bashiFootnote 30 also known as Mo’in‐ol‐Boka, pseudonym ‘Zabihi’” (Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2011:300) (fig. 3).

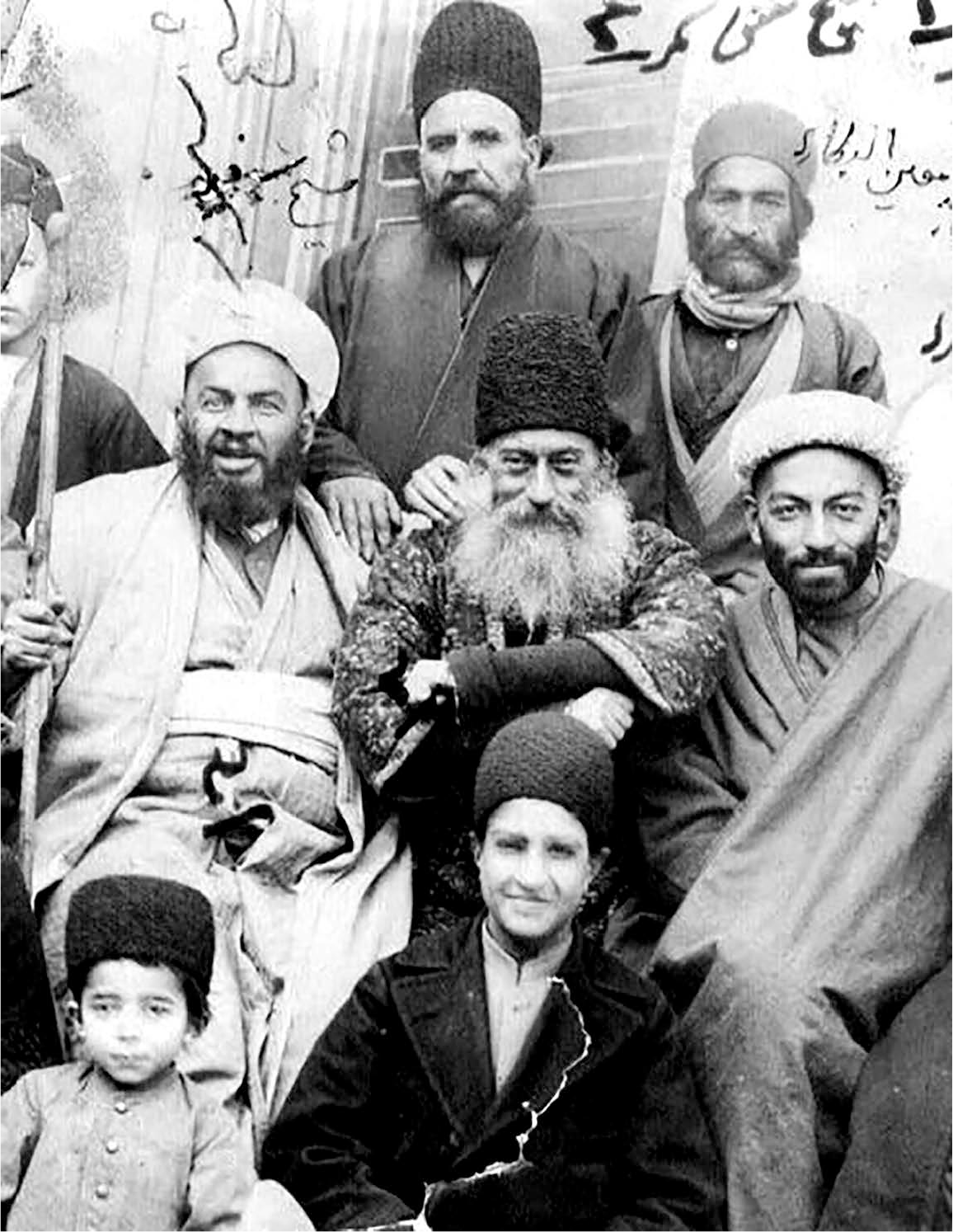

As further evidence, in manuscript 20157, written in 1833, the pseudonym for Mohammad Taqi appears in the last verse where he asks the Almighty for blessings, “Grant my prayers for a lengthy life / Grant all Fadayi’s wishes!” (in Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2011:150). Mohammad Bagher confirms his identity by adding a line that reads, “Hand‐transcribed by Mo’in‐ol‐Boka; accurate.” This famous annotation was, we believe, not Mohammad Bagher’s statement of authorship, but rather a written confirmation of the accuracy of these texts, using his official title: “Mo’in‐ol‐Boka.” This annotation appears on both old and new shabih’namehs that were written by authors other than him. Also, the dates of the texts composed by “Fadayi” are closer to the period Mohammad Taqi was active. Therefore, it is safe to assume that Fadayi is the pseudonym for Mohammad Taqi, while Zabihi is Mohammad Bagher’s pseudonym. As noted, Mohammad Taqi passed away in 1872, the year before the opening of the famous Tekyeh Dowlat, the court‐sponsored theatre‐in‐the‐round where shabih’khani was presented during the latter half of the 19th century. As photography at the time was used solely for family members of the royal court, no photo of Mohammad Taqi is known to exist. On the other hand, we have photographs of Mohammad Bagher (fig. 4).

Figure 4. Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka wearing his formal costume, equipped with his directing tools: manuscripts in his hand and waist scarf, wooden cane in his other hand, and a hat he used for signaling. (Photo courtesy of the Central Library of the University of Tehran, 7th Album, Number 227)

Mirza Mohammad Bagher

Mo’in‐ol‐Boka Mohammad Bagher, using the pseudonym Ta’ziyehsaz‐bashi (تعزیهسازباشی),Footnote 31 started his career assisting Mohammad Taqi while at the same time composing verses. We do not know the exact date when Mohammad Bagher began his work. During the Qajar era, most jobs were inherited (Tajbakhsh Reference Tajbakhsh1998:425). Male children apprenticed with their grandfathers, fathers, or uncles. As Mohammad Taqi’s nephew, Mohammad Bagher learned stagecraft and management from his uncle. Before being granted the formal title Mo’in‐ol‐Boka, Mohammad Bagher used his pseudonymous title, Ta’ziyehsaz‐bashi, in manuscript 20436. So most probably during his childhood he was his uncle’s scribe and assistant. According to sources such as Mostofi’s Description of My Life (شرح زندگانی من) ([1947] 1981), Mohammad Bagher was mistakenly thought to have been the son of Mohammad Taqi. This mistake found its way into publications such as Beyzai’s Theatre in Iran (1965). Most interestingly, the Qajar king Naser al–Din Shah — who appointed the director of Tekyeh Dowlat — in his daily notes after watching a performance during Muharram 1885 CE/1264 SH, writes, “this troupe was that of Mohammad Taqi’s son” (Qajar Reference Qajar and Badiei1999:234). This may have reinforced the mistake. It is understandable the two men were assumed to have been father and son given their close mentor‐protégé relationship. In LMDCIP manuscripts 20111, 20172, 20183, 20266, and 20389, Mohammad Bagher refers to himself as Mo’in‐ol‐Boka’s nephew, giving his uncle the title he himself later assumed. In manuscript 20111, Mohammad Bagher clearly refers to himself as “Mohammad Bagher, son of Mohammad Bagher, the late Mo’in‐ol‐Boka’s nephew.”

Perhaps it is because of these flattering, personally applied honorifics in a number of sources that the title Mo’in‐ol‐Boka has been mistakenly attributed to Mohammad Taqi rather than Mohammad Bagher by later scholars. In one authoritative source, Almaa’ser‐o val A’sa’r (المآثر و الآثار), written by Qajar court official Etemad al‐Saltanah (اعتماد السلطنه), Mohammad Bagher is clearly identified as Mo’in‐ol‐Boka (Etemad al‐Saltanah Reference al-Saltanah and Khan1889:240). In addition, there are no records of the Qajar ruler Naser al‐Din Shah granting a royal title to Mohammad Taqi. Considering the fact that it was highly uncommon for those with royal titles to be referred to by their birthnames, it is noteworthy that Mohammad Taqi is never referred to as Mo’in‐ol‐Boka by the Shah but rather as Mohammad Taqi or Mohammad Taqi Ta’ziyehgardan.

In photographs of Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka, whether during a shabih’khani or in group pictures, he is always seen holding a manuscript (see figs. 4, 6, 7, and 8). These manuscripts are likely sides rather than full scripts. One can assume that these sides are from the shabih’namehs being performed under his direction. Perhaps he wanted to assure his legacy as the preserver of shabih’namehs. This practice, incidentally, simplifies the task of identifying him among several photographs of shabih’khani performances of the era.

Among Mohammad Bagher’s significant contributions was collecting, preparing, and editing majleses composed by Mohammad Taqi. By doing so, Mohammad Bagher safeguarded these manuscripts for future generations. Mohammad Bagher also collaborated with prominent shabih’nevises of his time in composing and editing existing and new plays. It is thanks to such efforts that manuscripts from Tekyeh Dowlat performances were complete and accurate.

Mohammad Bagher also did the dramaturgical work of analyzing, annotating, and correcting defects in earlier shabih’namehs, adding technical commentary or suggesting improvements. During his time, shabih’ moz’hek (شبیه مضحک), a new comedic form of shabih’nameh, emerged. It is probable that Mohammad Bagher’s theatrical knowledge contributed to the development of the form. An example, Shast Bastan Div (شست بستن دیو, Shackling the Demon), is in the LMDCIP collection, manuscript 20241. Shast Bastan Div was performed at the Isfahan Festival of People’s Culture, or Jashn‐e Farhang‐e Martyrdom (جشن فرهنگ مردم), in 1977. In this play the people are terrorized by a demon. They call on the child Ali — cousin and future son‐in‐law of the Prophet Mohammad, and later the father of Imam Hussein — to help them. Ali ties the thumbs of the demon together, immobilizing him. Ali then makes the demon recant his evil ways. The demon is a comic figure. One of the highlights of the performance is when Ali mounts the demon as if he were a horse and makes him do humiliating tricks.

Eugène Aubin, a French diplomat who visited Persia in 1906 CE/1285 SH and 1907 CE/1286 SH, writes in his travel journals:

Mo’in‐ol‐Boka manages the stage. He, an old man with a white beard, first introduces himself [or the subject of the majles] to the audiences. He wears a long cloak and carries a wooden cane along with many paper scrolls in his waist shawl. Each paper is one of the roles in the ta’ziyeh. He has been administrating the royal ta’ziyeh for 37 years […]. (Reference Aubin1908:170)

Assuming that Aubin’s records are accurate, and taking into account the difference between the lunar and the Western calendars, Mohammad Bagher began his professional work in 1871. Because Tekyeh Dowlat was built in 1868 and inaugurated in 1873, Mohammad Bagher must have started his work in the old Tekyeh Dowlat or Tekyeh Abbasabad known as Tekyeh Haj Mirza Aghasi, which carried the name “Royal Tekyeh” before the opening of Tekyeh Dowlat. Mohammad Taqi’s ill health and eventual passing in 1872 might have led the patrons of Tekyeh Abbasabad to replace Mohammad Taqi with Mohammad Bagher.

A year or two after the short tenure of another shabih’gardan, Mosatafa Kashani (Boozari Reference Boozari1978:27–28),Footnote 32 Mohammad Bagher became the sole royal shabih’gardan. Mohammed Bagher’s theatrical knowledge and expertise even exceeded Mohammad Taqi’s, whose innovations left a clear mark on shabih’ performances. About the pivotal influence of Mohammad Taqi and Mohammad Bagher, Aubin writes, “This father and son have played an important role in the formation of the contemporary ta’ziyeh and other religious performances” (1908:171). (Of course, as noted, their relationship was actually uncle‐nephew.) Aubin reports that Mohammad Bagher had a formal position in the royal court, as indicated by his name, Mo’in‐ol‐Boka. During the month of Ramadan, he selected the best singers and musicians from Tehran and other parts of Iran and secured four‐month contracts with them (Aubin Reference Aubin1908:171). The abundance of Mohammad Bagher’s manuscripts in the LMDCIP collection is a testament to his endeavors developing the shabih’nameh.

The date of Mohammad Bagher’s passing is not certain. According to Ali Javaherkalam, it was 1908 CE/1287 SH. “On a rainy night, the roof of his house collapsed, and his wife and children perished. He miraculously survived but suffered mentally for a few months and died of heartbreak” (Javaherkalam Reference Javaherkalam1965:11). But in Abdolhossain Sepehr’s Mer’at‐ol‐Vaghaye Mozafari (![]() ), Mohammad Bagher died in 1905 CE/1284 SH: “On the 20th of Rabī’al‐awwal [25th May], Gholamali Semsar (غلامعلی سمسار) went to Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka to ask for his wages. Mo’in‐ol‐Boka was asleep so Gholamali calls out his name. When he steps out, the roof of his house collapsed killing his wife, sister‐in‐law, and six‐year‐old son” (Sepehr Reference Sepehr2007:779). But there is some evidence that Mohammad Bagher was alive in 1914. In the collection at the LMDCIP, there are two shabih’namehs with Mo’in‐ol‐Boka’s signature, Khoruj‐e Mokhtar (خروج مختار, Mokhtar’s Exit) (20193) and Mokhleb va Shahadate Ghanbar (مخلب و شهادت قنبر, Mokhleb and Martyrdom of Ghanbar) (20440) (see figs. 4 and 5 in SM). It is highly probable that these two are his last shabih’namehs. Another possible last play is Vafate Maryam (وفات مریم, Mary’s Passing) (20540), an unfinished shabih’nameh that is not completely his work, as he notes on the manuscript, “May God bless Seyed Mohammad Hussein Ta’ziehsaz and me, a humble servant, Mo’in‐ol‐Boka on 22nd Rajab 1332 [16 June 1914 CE/25 Khordad 1293 SH], while in ill health” (fig. 9). Based on such evidence, Mohammad Bagher’s passing must have been soon after 1914. A newly discovered note by Sayyed Jalal al–Din Tehrani (سید جلالالدین تهرانی)(1896–1987 CE/1275–1366 SH), indicates that Mohammad Bagher was alive around 1920 CE/1299 SH (see fig. 6 in SM). We do not know if this is true.

), Mohammad Bagher died in 1905 CE/1284 SH: “On the 20th of Rabī’al‐awwal [25th May], Gholamali Semsar (غلامعلی سمسار) went to Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka to ask for his wages. Mo’in‐ol‐Boka was asleep so Gholamali calls out his name. When he steps out, the roof of his house collapsed killing his wife, sister‐in‐law, and six‐year‐old son” (Sepehr Reference Sepehr2007:779). But there is some evidence that Mohammad Bagher was alive in 1914. In the collection at the LMDCIP, there are two shabih’namehs with Mo’in‐ol‐Boka’s signature, Khoruj‐e Mokhtar (خروج مختار, Mokhtar’s Exit) (20193) and Mokhleb va Shahadate Ghanbar (مخلب و شهادت قنبر, Mokhleb and Martyrdom of Ghanbar) (20440) (see figs. 4 and 5 in SM). It is highly probable that these two are his last shabih’namehs. Another possible last play is Vafate Maryam (وفات مریم, Mary’s Passing) (20540), an unfinished shabih’nameh that is not completely his work, as he notes on the manuscript, “May God bless Seyed Mohammad Hussein Ta’ziehsaz and me, a humble servant, Mo’in‐ol‐Boka on 22nd Rajab 1332 [16 June 1914 CE/25 Khordad 1293 SH], while in ill health” (fig. 9). Based on such evidence, Mohammad Bagher’s passing must have been soon after 1914. A newly discovered note by Sayyed Jalal al–Din Tehrani (سید جلالالدین تهرانی)(1896–1987 CE/1275–1366 SH), indicates that Mohammad Bagher was alive around 1920 CE/1299 SH (see fig. 6 in SM). We do not know if this is true.

Figure 5. Center: older Mohammad Bagher. (Photo courtesy of the National Library of Iran)

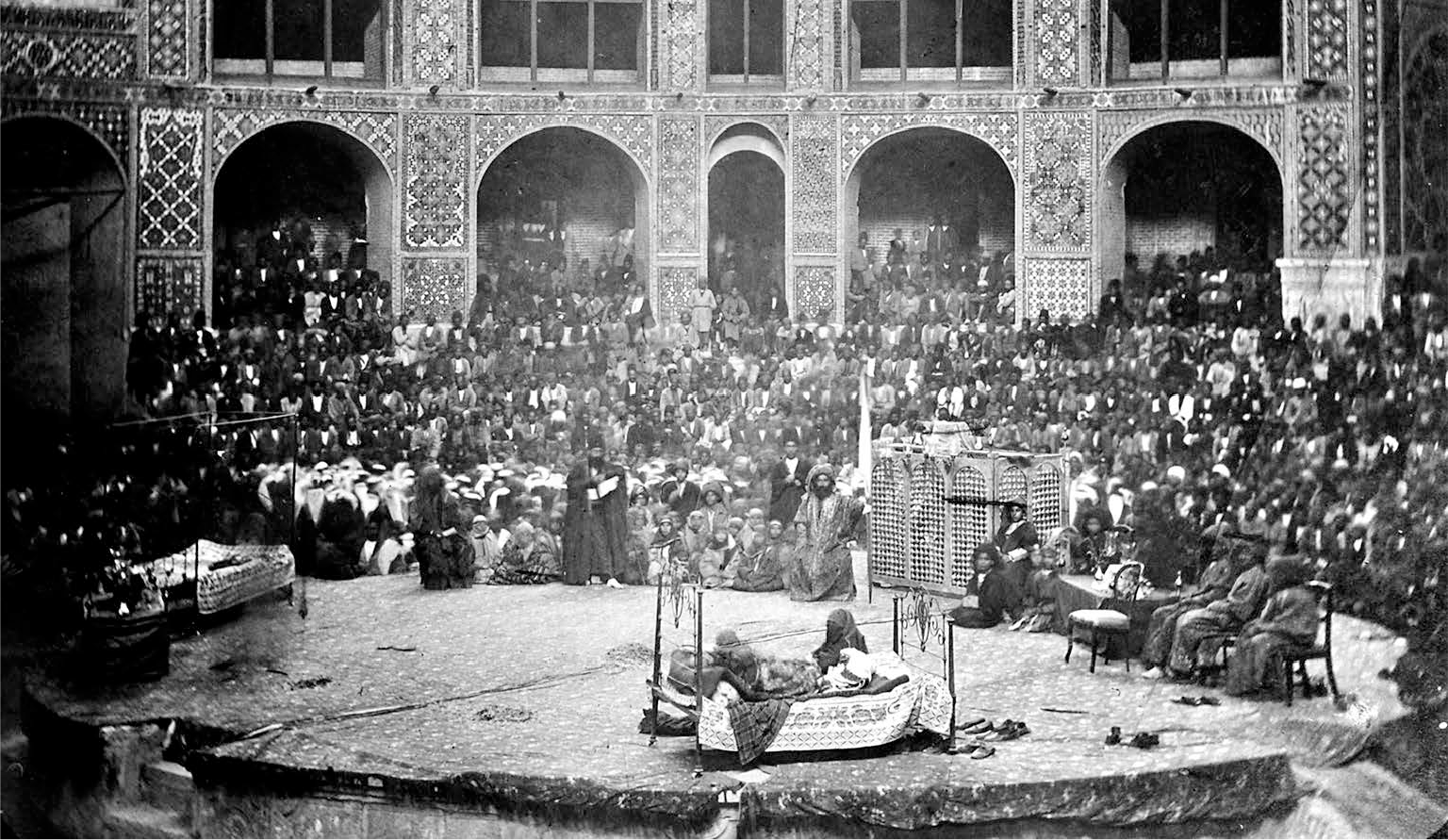

Figure 6. Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka (center) with manuscripts in hand during a shabih’khani in Tekyeh Dowlat. (Photo courtesy of Golestan Palace, 391st Album)

Early Signs of Theatre Directing in Shabih’namehs

Analysis of the accounts of non‐Iranian travelers, as well as the autobiographies, daily notes, and reports from foreign counsels mentioning Iranian shabih’khani, makes it clear that these non‐Iranians generally lacked substantial theatrical knowledge of Iranian performance traditions. What is recounted is astonishment and awe for this unfamiliar form of performance, or at best, an anthropological assessment of what they regarded as Iranian folklore. As Jamshīd Malik’pūr notes,

[Most] writings on the ta’ziyeh were not written from a theatrical viewpoint and as a result, they did not attract the attention of most Western theatre specialists. It was not until 1970 that the ta’ziyeh became known to Western theatre scholars. Peter Brook, after seeing a ta’ziyeh performance in that year, expressed his enthusiasm for its theatrical qualities. (2004:2)

Lack of attention to theatrical details in these 19th‐ and early‐20th‐century observations may also be explained by the fact that shabih’gardans were not in the habit of communicating their methods either verbally or in writing. Much in line with Eastern artistic practice, the shabih’gardans and shabih’nevises regarded the path to artistic expression as more valuable than the destination. The present was treasured more than future rewards; these artists shunned any form of recognition. The absence of any specific records detailing shabih’khani directing makes the newly found texts the only source to identify, even if only indirectly, the Iranian conception of theatre directing.

Signs of directing — of how to stage and perform the plays — can be classified into two groups: within the dialogue of the plays themselves, and outside the plays. While some directing can be hidden in subtexts, such as acts and movements implied by the dramatic action, others are written in annotations alongside the dialogue.

In general, a play text consists of dialogue and, sometimes, stage directions. Both of these can be discerned through analysis of shabih’namehs and evaluated by comparing the texts from different historical periods. Annotations written in the margins of the dramatic dialogue are particularly important for showing the growing importance of the director’s role over time. This is particularly evident in the LMDCIP shabih’khani manuscripts as opposed to manuscripts from the earlier Naseri period where there are no annotations.

Certain manuscripts in the LMDCIP corpus contain annotations that are directors’ notes that later evolved into concrete stage directions. Shabih’namehs of the Qajar era contain vivid, extensive descriptions, as in this annotation in manuscript 20206, which specifies a circumambulation of the stage:

Mr. Ali Akbar wearing armor enters riding on a horse. Goes around the stage once and exits. Then, the girl […] stands up swiftly. [Ali Akbar] gets off the horse. From a distance, he looks at her and walks slowly towards her. He then stops behind her and starts executing his role. (in Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2011:140; see fig. 7 in SM)

Figure 7. Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka (standing, front, second from right), shabih’nameh in hand, with his cast after a performance in Tekyeh Dowlat. (Photo from Moayer‐ol‐Mama’lek Reference Moayer-ol-Mama’lek 1983 :146)

As William O. Beeman notes, speaking of contemporary shabih’khani: “movement in an arc or circle depicts a long journey; movement in a straight‐line indicates actual distance” (Beeman Reference Beeman2003:11). Traveling in an arc also indicates the start of a battle or increasing tension. “Scene changes are indicated when a performer circles the platform” (Chelkowski Reference Chelkowski2005:17). These stage conventions are familiar to Iranian audiences. Indeed, such conventions seem to have evolved from the stage directions and directorial tools shabih’gardans used to control actors’ movements and provide scenic contexts without sets.

Similarly, in manuscript 20252:

Moses looks from in‐between his two fingers. Drumbeats are heard. Imam enters and sits. Shimr blows his horn. Then, Imam starts to sing. Imam Hossein wakes up. [Zaynab] kisses his throat. Ruqayyah takes the bridle and walks around [the stage]. (in Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2011:171; see fig. 8 in SM)

Figure 8. Mirza Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka with his ever‐present wooden cane in hand and manuscripts in his cummerbund. Like a Western orchestra conductor, he used his cane to lead the musicians and direct the movement of actors onstage. (Photo courtesy of the Central Library of the University of Tehran, 7th Album, Number 238)

“Looks from in‐between his two fingers” is a characteristic stage gesture unique to shabih’khani. It is a signal indicating supernatural vision. “This theatrical device known as a guriz” is a tool the director uses to indicate travel across space and time without changing sets (Riggio Reference Riggio2005:104). “Through the guriz, all ta’ziyeh drama expands beyond spatial and time constraints to merge the past and present into one unifying moment of intensity that allows the spectators to be simultaneously in the performance space and at Karbala” (Chelkowski Reference Chelkowski2005:23).

In manuscript number 20303, Shahadate Ghanbar va Mokhleb (مجلس شهادت قنبر و مخلب, Ghanbar and Mokhleb’s Martyrdom), Mohammad Bagher writes:

[Mokhleb] changes his turban. Mother answers. When they want to bury Mokhleb’s son between two walls, [Mokhleb’s wife] sings. After Imam’s verse, followers sing chavooshi. (in Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2011:204)Footnote 33

Written annotations such as these indicate that the shabih’nevises were well aware that they wrote not literary pieces but dramatic texts. In addition to dialogue, they specified actions and movements to create fully realized theatrical scenes. In manuscript number 20374, also by Mohammad Bagher, the annotated marginal notes read:

The Kaiser enters riding a horse. A group wearing European clothes enters with a wooden pallet, bells, instruments, sweets, fruits, etc. They place all on the pallet. After that, Hatef sings; the church people fall asleep. Another group, Armenians, come with a pallet [along with] bells, sweets, and fruit. After placing them on a tray, Hatef starts speaking. Malikeh goes to sleep. Malikeh turns around and kisses his hands. (257)

Similarly, in manuscript 20307 by Mohammad Bagher:

Approaching the Imam on a horse, Ibn‐e‐Shadad sings to him. Moslem laments on the Prophet’s grave. While he sings, Moslem rides a horse one round [a full circle], and stays still. Drumbeat. He gets off the horse and sits by the water. Moslem writes a petition. [Qeys] rides towards Imam. Qeys gets the message and rides to Moslem. Moslem sings while riding on the horse one round. The hunter shoots an arrow. And then Moslem sings. Moslem gets off the horse. (207)

In the majles Za’n‐e Nasrani (زن نصرانی, Nasrani’s Wife), manuscript 20225, the marginal comments describe what happens:

The slave woman prepares the bed. She brings a pitcher. The Christian wife wakes up, walks outside barefoot. Fatimah goes over to the corpse of Abbas. The Christian wife speaks over the corpse of the Imam. The slave woman talks to the corpse of the Imam. Fatimah makes a speech next to the Euphrates River. (153)

The shabih’nevis, who was often also the shabih’gardan, was well aware of what was needed to make a successful theatrical performance. In the manuscripts, he wrote notes on acting and movement to complement the dialogue. In other words, in addition to literary, religious, and musical knowledge, a shabih’nevis was required to have expertise in how to perform. As a shabih’gardan, his main focus was to harmonize the text and the performance, to know what were the most effective gestures, staging, music, costumes, and props. In a large number of the annotations, words such as “instantly,” “immediately,” “exit,” and “enter” and phrases such as “turn once around,” “turn once around and sing,” “turn once around and exit,” “go around the bed and then sing,” “go around, wake up,” and “fight and leave” are frequently found (in Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2011:106, 139, 153, 189, 210). Their main function is to create and control the rhythm of the performance. Such annotations determining the actors blocking and other directorial instructions were mainly in jongs, the full scripts. Jongs were used only by shabih’gardans, while the actors were given only the tumar, the sides.

Western Theatre and Shabih’khani

It may be tempting to suggest that the directorial functions in shabih’khani were borrowed from or influenced by Western theatre. However, the timeline of both traditions excludes this possibility. The annotations and stage directions written on shabih’khani texts date to before 1871 CE/1250 SH, years before the staging of the first European‐style theatre in Iran. The first European style proscenium stage in Iran was in the Dar ul‐Funun school’s hall (Tama’sha’kha’ne Dar ul‐Funun, تماشاخانه دارالفنون) from 1886 to 1891 CE/1264 to 1270 SH.

The first European‐style plays in Iran were written by Mirza Fatali Akhundov (میرزا فتحعلی آخوندزاده, known as Akhundzadeh in Iran; 1812–1878 CE/1191–1256 SH), a pioneering playwright of the Azeri Turkic language. His plays were first translated into Persian after 1871 CE/1245 SH by Ja’far Gharachehdaghi (میرزاجعفر قراچهداغی). Some of Akhundov’s works, such as Moosio Jorda’n (موسیو ژوردان, Mr. Jordan; 1872 CE/1250 SH) and Mola Ibrahim Khalil Kimiyagar ملا ابراهیم خلیل کیمیاگر), The Alchemist Mola Ibrahim Khalil; 1871 CE/1249 SH), seem to have been inspired by the comedies of Molière. Gharachehdaghi’s preface to the published Persian translations of Akhundov’s plays indicates that they did not attract large audiences. At about the same time, starting in 1873 CE/1251 SH, Naser al‐Din Shah and many aristocrats were the first members of the royal court to travel to Western Europe and Russia. Taking into account that the plays of Akhundov were published in Persian in 1871 CE/1249 SH, we may completely rule out the idea of European influence on the shabih’gardan director’s role. As noted, the annotated shabih’nameh documents we analyzed date mostly from before 1871 CE/1249 SH.

Indeed, the influence may be the other way round. Many similarities can be found between annotations on shabih’namehs and stage directions seen in the productions in Iran of the first Persian European‐style plays, indicating the possibility that shabih’khani may have had a major influence on Western‐style playwrighting and theatre production in Iran.

Comparing three different stage directions illustrates this possibility. The first is from the LMDCIP shabih’khani manuscript 20347 (April 1832 CE/Dhu al‐Qadah 1247 AH/Ordibehesht 1211 SH); the second and third are from early Iranian Western‐style stage plays. From manuscript 20347:

After the verse, a woman asks Zaynab for permission and goes towards Kolsum for a pledge [of marriage]. After a conversation with Kolsum, when Kolsum denies the marriage proposal, the woman comes to Zaynab, gets permission, and goes to Sakinah for a pledge. After a conversation with Sakinah, when Sakinah denies the marriage proposal, the woman returns to her husband and speaks [the following verses]. (in Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2011:238; see fig. 9 in SM)

From Mirza Aqa Tabrizi’s ca. 1871 CE play, Ashrafkhan: Hakeme Arabestan (اشرف خان؛ حاکم عربستان, Ashrafkhan; Arabian Ruler):

Mr. Karim takes the money and the contract and gives them to Mirza Tarar Khan and says these were sent by Ashraf Khan. At night, Mirza Tarar gives that money to the chieftain. The chieftain signs the contract and assigns his samite to Ashraf Khan. After three days, Ashraf Khan still waits for the contract; he writes a letter to Mirza Tarar and asks for him. (Tabrizi Reference Tabrizi1977:26)

From another play by Aqa Tabrizi written at about the same time, Hokoomate Zaman Khan‐E‐Boroojerdi (حکومت زمان خان بروجردی, The Reign of Zaman Khan‐E‐Boroojerdi):

Haji Rajab goes to the bath; comes out and enters the room. He puts the key to his cash box in front of Yazdanbakhsh and says […] (Tabrizi Reference Tabrizi1977:75)

Aqa Tabrizi (میرزا آقا تبریزی) (?–1915 CE/1294 SH) wrote the first Persian European‐style plays. Most interestingly, Tabrizi wrote both plays quoted above during the construction of Tekyeh Dowlat (Amjad Reference Amjad1999:102). Thus, he was most probably well versed in the conventions of the shabih’nevis and the practice of incorporating stage directions. He was also well aware of his contemporary playwrights, particularly the aforementioned Mirza Fatali Akhundov (Akhundzadeh), but their works differed greatly. They corresponded and their letters reveal their different conceptions of theatre and the performing arts. Akhundov was highly influenced by the realistic theatre in Tbilisi, Georgia, while Tabrizi’s work bears the marks of a shabih’nevis. We conclude that the Qajar and Naseri era shabih’namehs were developed free from European influence. Their innovations were their own original contributions.

Directorial Annotations in Shabih’khani

Because shabih’khani has very little in the way of stage sets, relying primarily on stage action, costumes, and props, these are of special interest. For example, in manuscript number 20200, “Place a white fabric on a pillow in a way to show the shadow of a black scorpion. The puppet designer [na’shsaz, نعش ساز] should make the third scorpion bigger” (in Kouchek‐zadeh Reference Kouchek-zadeh2011:135). Or for the new majles, Mahshar (محشر, The Day of Judgment), manuscript number 20436: “This number of actors and equipment is good for Tekyeh Dowlat and affluent audiences but should be cut by one third for smaller tekyehs and peasant audiences” (300). In manuscript number 20517, “Signs on each page indicate intervals that can be used or omitted when the majles needs to be shortened” (356).

There are notes on music and sound effects, such as, “Beat the drums, Habib throws in the stone” (20362); “Beat the drums” (20367); “Beat on the naqhareh”Footnote 34 (20432); “Israfil blows four times into the trumpet. Start music, open the curtain to heaven” (20436); “Beat on drums for a fight. Beat on drums for mourning” (20513); “Start mournful music” (20436); “Supporting characters sing mournfully” (20206); “Imam sings Chavooshi” (20265); “[Moslem] sings Chavooshi” (20486). Clearly music helped set the scene, created atmosphere, and facilitated changes in rhythm and energy.

In the shabih’nameh of the Naseri era, two innovative technical elements first appeared: lists of characters and lists of props and equipment (see figs. 10 and 11 in SM). These additions to the scripts, which facilitated the productions, were never seen by the public; it is safe to assume that these notes were used by the shabih’gardan during rehearsals. A list of characters can be seen in manuscripts written during Fath‐Ali Shah Qajar’s reign (see Chodźko Reference Chodźko1878; Pelly Reference Pelly1879; and Litten Reference Litten1929). However, a second list in these collections was seemingly added by Mohammad Taqi and Mohammad Bagher, who were the playwrights of many of the majleses. Although lists of characters can be found in early Persian‐language European plays, there are not usually lists of equipment or props (see table 1 in SM).

Figure 9. Handwriting of Mohammad Bagher at the end of Vafate Maryam (وفات مریم, Mary’s Passing), manuscript 20540. (Photo courtesy of the LMDCIP archive)

Figure 10. This sample of Tekyeh Dowlat’s posters is the oldest existing poster of shabih’khani and published here for the first time. (Photo courtesy of the Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies)

Figure 11. Women’s auditorium at Tekyeh Dowlat. (Photo courtesy of Golestan Palace, 391st Album)

Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka used stage equipment and techniques similar to those used by a modern‐day theatre director. For instance, there is evidence that he designed a crane that lowered the character of the Angel Gabriel from the ceiling of Tekyeh Dowlat onto the stage. Another device was a flaming chariot from hell wheeled around the stage. In Tekyeh Dowlat’s detailed financial documents, the crane is referred to as charkh‐e‐nozool‐e‐malaek (چرخ نزول ملائک, a pulley to facilitate the descent of angels) and the chariot as charkh‐e‐asbab‐e‐jahanam (چرخ اسباب جهنم, Chariot of Hell). Expenses paid to build the crane were 9 tomans, and to build the chariot it cost 20 tomans and 5 gherans, all paid in full.Footnote 35 The importance of such stage machinery can be assessed by comparing their costs with the wages for the most important actor, the man who played the role of Imam Hussein, known as the Imam’khan (Imam reciter), which was 15 tomans for approximately 10 performances (Bayani Reference Bayani2012:658).

As a manager, Mohammad Bagher pioneered the preparation of posters and brochures for each year’s performances at Tekyeh Dowlat (fig. 10). We cannot know exactly when these posters were first printed, but the oldest extant poster was designed for the majles Vorood Be Karbala (ورود به کربلا, Entering Karbala), performed on 6 December 1880 CE/3 Muharram 1298 AH/16 Azar 1259 SH, several years before the first European‐style theatre was performed publicly in Iran.

Among 16 existing Tekyeh Dowlat posters, three date to 1880 CE, nine to 1881, and four to 1884. These posters make clear that even though all performances were at Tekyeh Dowlat during the first 10 days of the month of Muharram, the repertoire changed every year and Mohammad Bagher planned, publicized, and directed a different set of shabih’namehs each year. The Tekyeh Dowlat posters he prepared are not only the first form of advertisement for any Iranian theatre, they are also the first for any artistic work in Iran.

Early Signs of Dramaturgy in Shabih’namehs

The primary duties of Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka were reading, reviewing, and editing old and new shabih’namehs, tasks primarily assigned to a dramaturg in contemporary theatre. Since Mohammad Bagher was a shabih’nevis, shabih’gardan, and head of royal shabih’khani of Tehran, he wrote critical annotations and suggestions on manuscripts and gave other shabih’nevises and sometimes shabih’gardans the chance to edit scripts and change performances. His remarks were often candid and brief: “Old, this is useless” (20474); or “This chant is new; it should become a fard [included in a side]” (20417); or “It is reviewed; it should become a fard” (20456). According to the latter annotation, “this fard is confirmed and can be used for shabih’khani.” At times he provided a more detailed analysis of the text. For instance, in Dafn Kardan Shohada va Jabal va Rezvan (دفن کردن شهدا و جبل و رضوان, Burying the Jabal, Rezavan, and the Martyrs; 20213), he suggests:

One dialogue suffices between Shimr and Ibn Sa’ad. No need for a dialogue between Imam and Darda’il. Cut giving water to Hurr, brother, boy, and slave. Start from [the part where] water is handed to Ali Akbar until the end. No need for Gabriel to sing after each martyr drinks water. This is to shorten. (see figs. 12 and 13 in SM)

Figure 12. Men’s auditorium at Tekyeh Dowlat. (Photo courtesy of Golestan Palace, 391st Album)

Along the same line are his annotations on manuscript 20411:

Reviewed. A brief passage must be added in the sixth majles. However, eliminating this passage will not be harmful. No need to add or erase. Some verses are needed for a dialogue between brother and sister. Some are also needed for a dialogue between mother and daughter in order to persuade the father not to kill Abdullah. Hatef’s chant in the name of Hussein is good in every way. (see figs. 14 and 15 in SM)

These examples show Mohammad Bagher’s abilities as a dramaturg, eliminating superfluous parts and adding dramatically necessary elements. He searches for ways to establish the appropriate pacing and dynamic between characters. He points out the flaws in the plots of the shabih’namehs and provides suggestions on how to adjust them. In some texts, he recommends taking one passage and using it in another moment in the performance. The following is a common note repeated in a number of texts:

After the messenger approaches the Imam, he starts reciting a quote from Jala‐Ol‐Oyoon (جلاء العیون, Washing the Eyes), about Loghman ibn Bashir on the pulpit, praising the Prophet. After this, Abdullah Moslem sends a letter to Yazid. As this is lengthy and irrelevant, I removed Loghman from the pulpit. […] Since there is no evidence of the Imam being present here, according to the hadith [حدیث], it is enough, and he shall be martyred here. However, as the dialogue with Imam is in the present tense, it can be used. The Imam can recite, if he desires, otherwise it is not necessary to adhere to the hadith. (20307; see fig. 16 in SM)Footnote 36

Such a novel, nearly revolutionary, prioritizing of theatrical needs over religious orthodoxy is a remarkable characteristic of the writings of Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka. His annotation on Ta’va’lode Ha’zrat‐e Isa (تولد حضرت عیسا, The Birth of Jesus) points to the unique conventions of shabih’khani:

After Gabriel looking through Jesus’s two fingers at Jesus’s invitation, [you can] add any passage you want. Then, read the second passage or all (of them) and then move to the next. (20155)

Authors of shabih’namehs placed no restrictions on text alterations and/or edits by shabih’gardans. Certain passages, called goosheh (گوشه),Footnote 37 may be added to the main storyline, becoming independent episodes occurring anywhere in a majles. In another document, one shabih’nevis writes, “Read a new goosheh […] in the funeral [scene] for the Prophet” (20458), clearly leaving the shabih’gardan in charge of selecting the goosheh and determining its placement in the performance. For example, “additional dialogues between the characters, Zaynab, Imam Ibad, and Sakinah can be used in the majles Vafate Zaynab (وفات زینب, Zaynab’s Passing), Asbab Pas Dadan (اسباب پس دادن, Returning Items), and Deyre Solomon (دیر سلیمان, Solomon’s Monastery)” (20500), indicating the use of gooshehs from different texts, borrowing from one another.

Every shabih’khani performance could be modified in order to comply with the needs of the organizer, audience, and actors as well as to take into account the resources available. Performances could be extended or shortened depending on circumstances, sometimes during the course of the performance itself. As both the author and director, Mohammad Bagher was conscious of the logistics of a performance and built notes regarding production into the majleses he wrote and/or directed. “Notations have been made for episodes to be used, which can be omitted if the majles is to be shortened” (20517). When text was added, it was necessary for shabih’nevises to refer to the sources of the borrowed verses, and also to document their own shabih’namehs. Some titles of shabih’namehs in the LMDCIP collection include Mohammad Bagher’s notes of his sources. For example, from different manuscripts: “Majles Aroosiy‐e Fattemeh (عروسی فاطمه, Fatimah’s Wedding) is adapted from Jalal‐Ol‐Oyoon, a book written by the late Allamah Majlesi” (20373; see fig. 17 in SM); “Mojezeye Imam Hassan dar Chin (معجزهامام حسن در چین, The Miracle of Imam Hassan in China) is a quote from Mola Aqa Darbandi (ملا آقا دربندی)” (20450); “Yousef Payambar (یوسف پیامبر, Prophet Joseph) is based on the book Yusuf and Zulaikha (یوسف و زلیخا, Joseph and Zuleikha) (20522); Khoruj‐e Mokhtar (خروجمختار, Mokhtar’s Exit), accepted by all ulama (علما)Footnote 38 and adapted by myself [Mohammad Bagher] from Jala‐Ol‐Oyoon written by Allameh Majlesi, original hadith is correct and without errors” (20193; see table 2 in SM).

There is even an instance of Mohammad Bagher criticizing his own writing. On top of the first page of his majles Shast Bastan Div, he notes: “This has poor quality. Mirza Ba’ba’y‐e Nayeb’s (میرزا بابای نایب) text is better [than mine]” (20242). This simple note points to Mohammad Bagher’s pursuit of a better play, modestly dismissing his own creation.

Theatre Directing in Europe and the Work of the Shabih’gardan

According to histories of theatre directing in Europe, certain tasks of modern‐day directors initially were performed by playwrights, playwright‐managers, and actor‐managers. However, in the last quarter of the 19th century the modern director emerged. The history is well‐known, from Ludwig Chronegk (1837–1891), the artistic director of the Meiningen Ensemble created by Georg II, Duke of Saxe‐Meiningen (1826–1914); on to André Antoine (1858–1943); Edward Gordon Craig (1872–1966); Konstantin Stanislavsky (1863–1938), and the multitude of directors who followed. The Meiningen Ensemble toured Europe from 1874 to 1890. Under the Duke’s watchful eye and Chronegk’s directing, the ensemble became famous for choreographed crowd scenes, historically accurate sets, costumes, props, and ensemble acting, rejecting the star system (see table 3 in SM).

Aubin’s eyewitness report and the materials we have analyzed from the LMDCIP, the Malek National Museum and Library of Iran, and private collections clearly show that Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka did the work of a director by European standards several years prior to the Meiningen Ensemble. The evolution of the director in Iran started with Mirza Mohammad Taqi Ta’ziyehgardan and was revolutionized by Mohammad Bagher.

The first American Minister to Persia, Samuel Greene Wheeler Benjamin, saw performances towards the end of Tekyeh Dowlat’s first decade. He wrote:

The entire performance was directed by a prompter, who walked unconcernedly on the stage, and gave hints to the players or placed the younger actors in their position. At the proper moment also, by a motion of the hand, he gave orders for the music to strike up or stop. But it was curious how soon I ceased to notice him at all; indeed, after a short time I was scarcely aware of his presence. (1887:392)

At about the same time Abdullah Mostofi wrote:

Mo’in‐ol‐Boka carries all actors’ manuscripts, a stack of well‐organized paper in his waist shawl [figs. 4, 6, 7, 8]. This was in case any of the actors forgot theirs, so he had a spare. He manages his work very well. All his commands are thoroughly obeyed by all 100 actors and musicians […]. He gestures with his cane towards the actors and the musicians to give his instructions to start or stop, in a dignified manner. Even if among the audience, someone sitting in a private balcony or around the stage, makes a sound, Mo’in‐ol‐Boka would cast a solemn look at them for them to stay quiet. ([1947] 1981:297–98)

British missionary Clara Rice, living in Iran approximately between 1910 CE/1289 SH and 1912 CE/1291 SH, describes how “some of the actors bawl, others cannot be heard; the prompter is always in evidence” (1923:234). According to her notes, it becomes clear that the stage‐director/prompter (ostad) was constantly on the stage in the middle of the scene with a piece of paper in hand. He would carry the roles of all actors, directing and assigning them to their proper places; he “never quitted the stage, and gave frequent explanations of whatever appeared unclear or ambiguous” (Mounsey Reference Mounsey1872:314).Footnote 39

Referring to Mirza Mohammad Taqi, Mostofi writes, “anywhere he found a talented person, Mirza would follow him, and by force or promise, prepared that person for shabih’khani” ([1947] 1981:290). This method was also practiced by Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka. Posters from Tekyeh Dowlat confirm this (fig. 10; fig. 18 in SM). Actors’ names are followed by their city of origin in these posters, such as Kani, Kashani, Kermani, Tafreshi, Mazandarani, Tehrani, Khorasani, Yazdi, Shemirani, Mahalati, etc.Footnote 40

Mohammad Bagher selected the best performers for four‐month contracts. Rehearsals lasted three months. The last month, the month of Muharram, was dedicated to the performances. The troupe toured to different tekyehs in the area with shabih’khanis starting in the early morning and continuing till late at night with up to seven performances a day.

Even more than his European counterparts, Mohammad Bagher controlled the productions for which he was both director and dramaturg. He also monitored other shabih’khani troupes in Tehran, occasionally loaning them his actors. He selected, edited, and wrote plays; he designed posters and supervised the repertory; he adapted literary texts for the theatre; he analyzed and compared texts with related religious stories; he introduced innovations in shabih’khani verse and music; he supervised performers, including their movements, gestures, and the correct ways to speak the parts; he added physical features to mythical characters, simplifying them for audiences; he searched for and recruited the best actors from different cities; he employed professional musicians to teach the actors different Persian musical dastgāhs (دستگاه) or modes; he led long hours of music rehearsals and directed the musicians during performances; he designed costumes, props, stage machinery, puppets, and masks; he employed animal trainers and choreographed horses, camels, elephants, lions, pigeons, etc.

Mohammad Bagher was onstage throughout the performance leading his actors and musicians in real time. He oversaw actors’ entrances and exits, carried and placed props on the stage and even acted as the leader and reference point for audience participation and collective mourning, which included chest‐beating, self‐flagellation, and chanting. His presence on the stage did not interfere or distract. On the contrary, it became one of ta’ziyeh’s conventions.Footnote 41 The result were performances that shunned realism, that focused on the theatricality of shabih’khani. Under Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka’s leadership, shabih’khani was transformed from a historical reenactment into a symbolic, creative theatre genre. He emphasized theatricality rather than religious orthodoxy, with themes such as speculations on the afterlife, spiritual redemption, and the supernatural (see fig. 19 in SM).

The Formation of Directing in Shabih’khani

Before Mohammad Taqi and Mohammad Bagher the shabih’gardan was similar to the Western actor‐manager. Both, but Mohammad Bagher especially, transformed the shabih’gardan into a professional director. He was recognized in Iran for his official work as director of Tekyeh Dowlat. The first directors in Europe and in Iran had no knowledge of each other, yet what they did and when they did it coincide remarkably, offering us a new intercultural perspective on the emergence of the modern theatre director.

Theatre historians have paid little or no attention to the development of directing and dramaturgy outside Europe. The newly rediscovered shabih’khani manuscripts from the Qajar era in Iran show that directing and dramaturgy were practiced in traditional Iranian theatre starting in the late 18th century and further developed in the 19th century.

Sophisticated directorial techniques for shabih’khani in late 18th‐ and 19th‐century Iran responded to the need to create highly effective performances for remarkably large audiences. If all forms of theatre are reliant on their audiences, it will not be surprising that, in the Naseri era of the Qajar Empire, shabih’khani, with over 20,000 spectators at each performance in Tehran’s Tekyeh Dowlat and large audiences in other venues (Beyzai Reference Beyzai1965:129; Etemad al‐Saltanah Reference al-Saltanah and Khan1889:58), demanded high technical and theatrical competence (see figs. 11 and 12). The boundless appetite of Iranian audiences for this kind of theatrical presentation resulted in a wealth of shabih’khani performances throughout Iran, driving ever more elaborate technical, theatrical, directorial, and dramaturgical innovations.

In an increasingly religious era, Mohammad Bagher Mo’in‐ol‐Boka’s frequent rewriting and editing of historical religious tales not only failed to raise opposition from the clergy and the public but enjoyed widespread acclaim and popularity. His innovations in stage direction, movement, and theatrical reform in the Naseri era shabih’nameh is a clear indication of his theatrical knowledge. While his predecessors wrote verses that were often unperformable, Mohammad Bagher resurrected and edited texts that he deemed suitable for large audiences, recreating them as splendid works of theatre. The technical and theatrical duties of shabih’nevises and shabih’gardans and their development into a professional theatrical practice, as revealed in these newly discovered manuscripts, tailored shabih’khani to the society it served and the stories it told.

To view supplemental materials related to this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1054204321000745.