One of the most consequential aspects of global climate change is the rise of human migratory flows prompting attendant problems of overwhelmed reception and absorption resources in nations of arrival. Lack of employment, housing, and acculturation skills often lead to the criminalization of refugees and their detention and incarceration. In a 2021 article detailing how climate change is challenging criminal justice systems, law professor Laurie Levenson makes 10 recommendations on how to prepare, several of which emphasize more aggressive and punitive defenses. These range from lengthier sentences for environmental crimes and criminal fraud charges against companies that scheme to profit from climate change to developing alternative sites to house the incarcerated if climate change renders current prisons unusable. A range of threats to national security are also described, including instability and extreme weather events prompting an increase of migrants and refugees with a surge in global climate migration. Footnote 1 Rehabilitation, the future-facing twin of carceral punishment, is not discussed.

Responding to Climate Change through Prison Rehabilitation

What is referenced in Levenson’s article as a possible future scenario is climate migration from North African coasts to the West. Yet in fact, this form of migration has been underway for nearly a decade in Italy. Since 2016 sea landings of migrants from Nigeria, Tunisia, Guinea, and other locales constitute a significant portion of migrants arriving in Italy as a result of environmental climate changes and violence (see Migrants-refugees.va 2021). Some of these migrants end up incarcerated, with refugees now making up a disproportionate percentage of inmates in Italian prisons. In 2022 Italian prisons were over capacity at 107.4%, with foreigners making up 31.3% of those incarcerated, yet only 8.4% of the total population living in Italy are foreigners (Poletti Reference Poletti2022). The human rights watch group NuoveRadici argues “the root of the problem lies in the crimes committed, those due to lack of integration” (in Poletti Reference Poletti2022). Footnote 2 Indeed a 2014 report on Italian prisons argues the image of the migrant in Italy has “gone through a process of degradation and dehumanization” in part because many do not have a permanent home or employable skills (Ronco et al. Reference Ronco, Torrente and Miravalle2014:1149).

Despite high rates of migrant incarceration, Italy is at the forefront of addressing surging migrant numbers with novel prison rehabilitation programs. Performance, as well as deliberate attention to environmental and climate change, figure prominently in the success rates of these programs. Exploring why culture-based and sustainability-focused prison rehabilitation training programs are so effective with these incarcerated populations invites a consideration of the Italian model and its unique reach through a performance of cultural belonging as a possible framework for other nations. Mandated by the national government to address overcrowding and a lack of effective rehabilitation programs, among other problems, Italian prisons have developed innovative rehabilitation programs focused on employment training in exclusive food and fashion sectors through labor that is a de facto rehearsal for a return to the outside world, and in a newly rescripted role. Footnote 3 For ecomigrants caught in the carceral net, job training in ecominded and climate-conscious cultural industries can be a powerful way for them to perform labor that resists the same exploitative models of production and consumption that are part of the causal disasters leading to climate migration. In short, the Italian programs seek to address both the cause of ecomigration and the fallout from climate-induced increases in the incarcerated population. In a radical move, these rehabilitation strategies implicitly link engagement with nationalism through the production of sustainable Italian cultural commodities and an active regard for the planet. They bend the arc of justice toward rehabilitation of not just the inmate but the world.

For the past two decades I have researched the use of performance in prisons as a medium of expression and self-authorship for inmates as well as a means of curated spectatorship for a public curious about the trauma of incarceration. In the spring of 2022, I expanded my research to Italy with a focus on the performative qualities of job training as rehabilitation for inmates. Footnote 4 After visiting 10 exemplary rehabilitation programs concentrating on the production of handmade Italian food and fashion products, I found a different relationship to social power dynamics where instead of boss and worker, “artisan” and “culture consumer” defined the exchange of labor for aesthetic object and experience. I define performance broadly in the interest of providing a nuanced understanding of the vitality, complexity, and influence of how bodies and sensibilities are shaped and regulated in penal institutions. Since the skills these job training programs are developing focus on artisanal food products and handmade fashion items, all of them distinctly Italian, there is a fascinating coding of nationalist identity embedded in the rehabilitation labor activities. Footnote 5 This extends to the signature products the programs create, tagged “Made in Italy,” a double meaning that references the newly acculturated immigrants as well as their edible or wearable products.

Focusing on developing the person, not just honing their labor, a rehabilitation program like Rio Terà dei Pensieri creates employment opportunities for inmates and those recently released from prison. The organization emphasizes social and relational skills of how to work with others, what to wear, and emotional reflection with guidance from volunteer psychologists. Vania Carlot, director of the Rio Terà cooperative, sees the social and psychological training as the most important tools inmates learn: “They’re used to more negative interpersonal relationships, especially within a prison context that’s crowded and where they have to confront a variety of other cultures, often with negative results,” she explains. “It’s not as important that they learn this work but that they learn how to work,” she continues, referencing the nuances of becoming attuned to Italian work culture (Carlot Reference Carlot2022). Footnote 6 Performance as well as attention to environmental and climate change factor prominently in many of these novel Italian prison rehabilitation programs, which center on rescripting the narrative of public presence by way of graduating incarcerated foreigners into Italian cultural life with high-status employable skills as well as social skills as newly enfranchised members.

Exploring why culture-based and sustainability-focused prison rehabilitation training programs are so effective with these incarcerated populations in Italy invites a consideration of the potential of the Italian model for other nations struggling with over-incarceration, high recidivism, and a public weary of pronouncements about a climate catastrophe destined to exacerbate many of the problems of migrant incarceration.

Cultural Belonging through Prison Rehabilitation

On the quiet island of Giudecca, just across the canal from Venice in Italy, Esther Footnote 7 stands on the Fondamenta del Carcere, the street in front of the Giudecca Women’s Prison. Footnote 8 It is a cool Thursday morning in early April, and she is carefully arranging bins filled with small bunches of chard, carrots, and asparagus, fresh organic produce picked that morning from the 6,000 square meters of vegetable gardens inside the prison compound. Three years into her prison sentence and speaking in Italian with a sprinkling of English words inflected with an African accent, she explains that tending the garden is difficult, especially in the summer heat. Yet the opportunity to be outdoors caring for the plants and, one morning a week, stepping a few feet outside the prison gates under supervision to sell her harvest allows Esther to perform the proud host, introducing customers to these little artifacts of her care and physical labor. “I never worked with plants or in gardening before,” she says to me, adding that once released, she would like to continue working in gardens. “It’s really nice to be outside, free, in the fresh air,” she says softly. She smiles as she moves from bin to bin, tenderly plucking off wilted and brown leaves from the greens and rearranging jars of organic soaps and lotions scented with herbs from the gardens she tends.

A 20-minute vaporetto boat ride away, 29-year-old Julian stands in front of Process Collettivo, a small storefront at the edge of Venice’s high-end shopping district just off Saint Mark’s Square. A skilled skier from the Italian and Swiss border, he was recently released from the Santa Maria Maggiore prison in Venice and is now on parole. Framed by a large banner above the storefront that reads “#MadeinPrison,” Julian paces the sidewalk excitedly, displaying one of the shop’s unique designs, a small pencil case he has individually sewn out of a discarded PVC advertising banner that bears the image of a photo of denim fabric. The label on the small case proclaims its brand, Malefatte Venezia (misdeeds Venice), a consciously ironic reference, and marks it as the distinctive environmentally friendly product of the Rio Terà dei Pensieri Cooperative. Rio Terà is a cooperative of prison training programs producing stylish Italian products made by inmates in local prison workshops run by community volunteers and cooperative employees.

A two-hour train ride away in Milan, Caterina Micolano, president of Cooperativa Alice, oversees a sewing workshop filled with women from the San Vittore prison, all of them trained in her workshop classes as skilled seamstresses who repurpose precious fabrics from prestigious Milanese fashion houses into one-of-a-kind women’s fashion. By repurposing the fine leathers, fabrics, and luxury products that are customarily thrown away to maintain scarcity and high prices, Micolano’s workshop reengineers the focus, supplying both workers and consumers with the sensual pleasures of interacting with beautifully made and practical products. “We are not doing this training for charity,” Micolano says, “but because we want the system to function; it’s the work of being a citizen to do this. We produce the instrument and furnish content through sewn goods. What others call a market; I call society. Together we can educate people in sustainability” (Micolano Reference Micolano2022).

Figure 1. Customers at the Thursday morning market on the sidewalk outside the women’s prison on Giudecca Island across the canal from Venice. Here women detainees sell the fresh produce they grow in the prison’s courtyard gardens sponsored by Rio Terà dei Pensieri Cooperative, 2022. (Photo by Janice Ross)

The food and fashion focus of all three prison rehabilitation training programs represented in the above vignettes are deliberate in their use of climate-conscious green and repurposed materials and their methods to market their products as well as the makers to a global society often indifferent to both climate change and the incarcerated. The fashion items use fabrics that would otherwise be discarded and all of the Malefatte bags and accessories are made using cast-off PVC advertising banners, postponing the disposal process. This metaphor of giving a second life to discarded materials and people echoes through marketing language and images for many of these programs.

As these rehabilitation scenarios illustrate, climate change and performance intertwine in these inmate rehabilitation programs in subtle yet profound ways. Part of what makes such production labor meaningful and the purchase of prison-made products part of an ethical exchange is the intentionality of those creating these programs — they model tending to migrants and the environment as paired urgent ethical projects. These projects represented by Esther, Julian, and Cooperativa Alice are just three of the more than a dozen gourmet food- and fashion-focused prison training programs that have proliferated over the past three decades for detainees in Italy’s 205 prisons. Rather than casting inmates and those paroled as societal outcasts, these initiatives expand and complicate the relationship between prison and performance to take advantage of the public’s fascination with what criminologist Michelle Brown calls “penal spectatorship” (2009:8). Here, however, it is displaced into an active penal consumerism.

Despite a robust body of scholarship on prisons as sites saturated with performances, rehabilitation programs have been left out of most performative analyses, yet they are a prime location with a uniquely dense core of performance essential to their practice and efficacy. In contrast to Italy, in the US much prison labor is poorly paid, demeaning, and uses minimal skills to mass produce staples for prison industries, like mattresses and uniforms, items that reinforce a denigrated and socially estranged status for the inmate. What makes the Italian model so radical is that when a customary regard of prisons as sites of disappearance and shaming is flipped and instead they are perceived as sites of new paradigms for vulnerable members of society and culture industries premised on waste and destruction, change can be profound. Systemic changes in the regard of some of those deemed most expendable in a nation at the front lines of these global politics has the potential to reverse a momentum of destruction into one of reconstruction and social repair.

Figure 2. The nonprofit Process Collettivo’s retail store selling bags made by detainees — part of Rio Terà dei Pensieri Cooperative, financed in part by American artist Mark Bradford. Venice, Italy, 2022. (Photo by Leigh Biddlecome)

Penal spectatorship — what Brown defines as imagining the punishment of incarceration and the infliction of pain from afar — is operating in these rehabilitation programs but legitimated in novel ways. In a few programs one encounters the inmate directly — e.g., Esther’s rotation selling the Giudecca produce and Julian’s turn at sales in the shop in Venice. More typically it is the artifact of their new activities — handmaking cultural products — that documents their transformation and at the same time the public’s contact with prison rehabilitation. Like penal spectatorship, climate change has a cultural hold on people from a distance, allowing them to justify their inaction. Purchasing a food item or article of clothing or an accessory from one of the Italian prison rehab programs with their inescapable focus on second chances and reuse of materials pushes awareness toward the climate catastrophe that set in motion those incarcerated lives making these commodities.

In other words, in purchasing vegetables from Esther, a pencil case from Julian, a meal from InGalera, or a couture dress from Alice Cooperativo San Vittore, one is buying a small, preserved performance — his labor, her transformation is embedded in it. It’s an artifact of her pain but also her metamorphosis, his vision. The intimacy of these changes is reflected in the small and personalized scale of Italian rehabilitation programs, which on average only accommodate 5 to 15 inmates at a time. Despite their modest scale, their high success rate of lowering recidivism suggests that beyond the marketability of the products, there is a meaningful personal transformation. Esther’s and Julian’s pride in what they create is a public testament to hours of labor, focus, and discipline. This is the work of rehabilitation that is customarily invisible and forgotten. These particular handmade prison industries subvert the anonymity of prison labor, making each personal achievement into an artifact that is enjoyed by an appreciative public. It is not just the marketability of the products sold that matters but how inmates’ engagement with carefully scripted labor practices in the service of creating objects of cultural value shifts how current and former inmate participants move in the world, literally.

Inmate training programs such as Rio Terà, Cooperativa Alice (Sartoria San Vittore), InGalera, and Malefatte have growing visibility and impact with a total of 2,500 inmates involved across the country. Viewed in the context of the 60,000 people currently imprisoned in Italy, the success rate of these growing training programs and their reach is significant. Program leaders cite a 17% recidivism rate for those who do the training and continue working after they are released versus the national average of a 70% recidivism rate for those who matriculate through the Italian criminal justice system without completing a work-training program inside (Della Morte Reference Luisa2022). Footnote 9 Investment in rehabilitating imprisoned individuals through training in distinctly Italian craftsmanship and skills, compensated by livable wages, and then honoring the released individual as part of an inclusive society are the animating objectives of Cooperativa Alice’s San Vittore tailoring workshop. “Behind every object is a human,” proclaims their website. “Not charity, just work” (Cooperativa Alice Reference Alice2021).

Figure 3. Detail of Malefatte bags made by Rio Terà dei Pensieri Cooperative detainees from recycled PVC. Venice, Italy, 2022. (Photo courtesy of Malefatte Venezia)

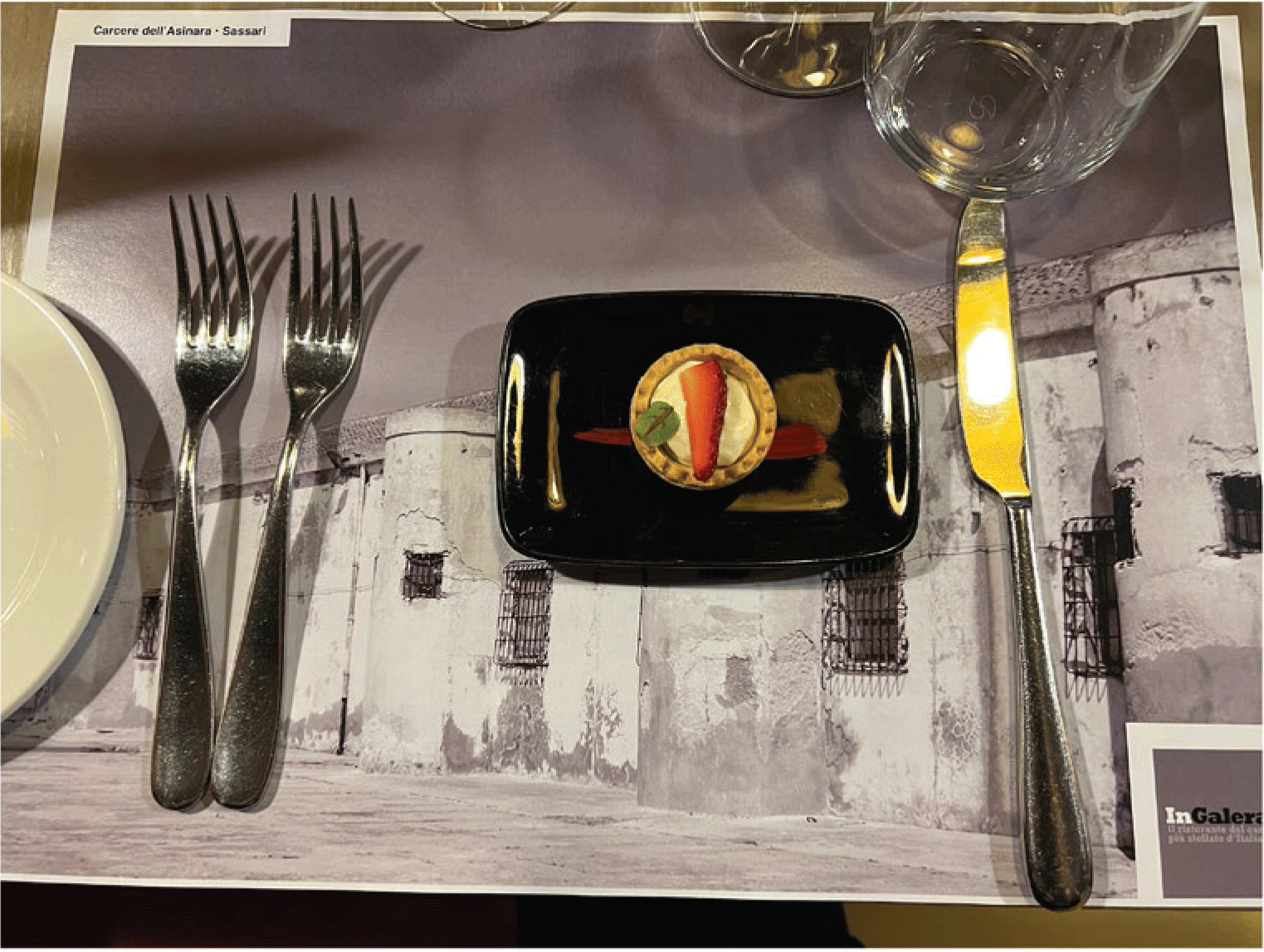

A distinctive sophistication marks the Italian prison industries and their products. For example, the famed Michelin-rated InGalera restaurant, located in a former conference room for correctional officers inside Bollate prison in Milan, features inmate-made nouvelle cuisine — such as an amuse-bouche appetizer arranged like a trompe l’oeil miniature pie and served atop a placemat imprinted with a stark photo of an old prison wall. Exploring these undertakings reveals the layers of scripted behaviors and movements shaping life inside and, just as pointedly, life though rehabilitation as one is preparing to transition back into the world outside. Rather than being trained to leave prison primed to be a cog in some anonymous industrial wheel, the graduates of these Italian prison training programs emerge as artisanal pastry chefs, organic gardeners, and fine seamstresses. Doing time and doing rehabilitation both have distinctive choreographies, behaviors that signal one as disciplined and compliant with institutional and community codes. The publics who consume the food and fashion products of these Italian prison rehabilitation programs complete the performance metaphor through their interactions with their products as aesthetic experiences. In serving as spectators and consumers of the food items, dining experiences, and wearable fashion provided by the trainees, the public engages with the project of punishment in a mediated relationship. The incarcerated are not present and instead the consumer interacts with the beauty and tastes their labor has produced — and all is in the shadow of climate migration.

Figure 4. Placemat with photo of old prison and place setting framing an elegant amuse bouche appetizer at the InGalera ristorante in Bollate Prison. Milan, Italy, 2022. (Photo by Janice Ross)

The larger public impact is evident. Walking through urban centers of Venice or Milan it’s not unusual to see smartly dressed Italians sporting the distinctive Malefatte shoulder bags and computer totes. Honoring Covid restrictions in April 2022 people patiently lined up outdoors waiting for their chance to enter the bakeries, patisseries, and retail shops selling coveted detainee-made comestibles and wearables. When one man, spotted in transit on a Venetian vaporetto and sporting a Malefatte Venezia shoulder bag, was asked how he knew about the brand before purchasing it, he exclaimed, “Everyone in Venice knows about Malefatte products!”

Instead of “warehousing” people in the criminal justice system, having them craft products of recycled materials carries a more positive framing of change, invention, and repurposing. The fact that the materials the inmates are working with include recycled objects and fabrics make Italian rehabilitation programs particularly relevant in this period of climate catastrophe. Writing in an essay in the previous TDR on Peripeteia, Lindsay Goss (Reference Goss2021) challenged the passivity of theatre spectatorship as waiting for someone else to take action, suggesting this same passivity is operating with the climate catastrophe. In serving those who have been literally set adrift by climate change, these Italian prison rehabilitation programs are using one of the most precarious spaces of the human condition — prisons — to prompt an active engagement with embodied suffering and the human consequences of climate catastrophe. Perhaps conjoining two already deeply interrelated crises impacting nations struggling with climate emergencies — prison reform and taking action to address climate change — can give new momentum to linked climate and criminal justice repair.