The camera sees only what it can. The eye sees what it wants. The desirable quality of “camera presence” — now everywhere in evidence (or not) in a hypermediated world — is the art of making the camera see what the eye wants. What the eye most wants to see is someone who is “there,” even when the whole point of being before the camera is that someone is in fact somewhere else. How does anyone learn how to be there when clearly not there? As a guide to the perplexed, self-help advice abounds in cyberspace. A web searcher looking for instruction will find clickbait oracles who promise to share one version or another of the secret recipe for the special sauce of presence. Such wisdom comes to the searchers directly and intimately in the second person (the du form, if English still had it), which is a rhetorical device that I will adopt and repurpose in this article for sympathetic emphasis and solidarity.

“You” the online searcher (formerly “thou”) will find feel-good professional nostrums, all saying similar things, characteristically rich in paradox but gutted by irony. “Presence is the absence of a filter between you and the audience,” a typical opening gambit goes: “It’s You authentically showing up as You. Your camera presence is your alignment visually, verbally, and emotionally. If you are worried and distracted, it will show up in your eyes and facial muscles” (Brown Reference Brown2019). So presence is an absence? What then can workaday “you” take away from this contradictory promise of an authentic “You,” unworried and undistracted, which must originate in an erasure, like the face of a fully armed Athena sprung from the empty head of Zeus?

The bottom line is that nothing suitably authentic can be added without subtraction. To be present on camera “You” (capital “Y”) can’t be “you” (small “y”), but something or someone better. This elusive You, the one with placid eyes and flaccid facial muscles, is the one who can align its aspect, address, and affect at will to project the look of serene self-possession. Being present as You, therefore, requires leaving something (and maybe a lot) of you behind. Tips about twitch-resistant acting techniques for camera include this two-word classic from actor Michael Caine, explaining how to create a sense of presence in close-ups: don’t blink (FilmKunst [1987] 2013). The better version of You must keep its eyes open for the full duration of the shot because closing and opening them rapidly weakens your presence while propping them open strengthens it. The camera’s unblinking eye thereby flatters the countenance of its aspiring double — your face. The longer you can speak with your eyes wide open, the more the authentic You can appear. The threat of embarrassment really stems from hyperpresence — too much, rather than too little of you. The fact that such an Argus-eyed stare is impossible for most people to sustain for the length of a typical zoom close-up dramatizes how difficult achieving presence can be. Your egregious eyelids, fluttering helplessly like wounded birds, fill the screen, preventing that lesser but better You from coming across in its more carefully curated fineness of being. Media-industry personalities with a highly rated camera presence are called “talents” for good reason.

Taking the long view, historians of performance can show how apparently disposable pop-up theories of camera presence actually emerge from a theatrical tradition of considerable depth (Vardac [Reference Vardac1949] 1968; Brewster and Jacobs Reference Brewster and Jacobs1998). The sources of that tradition reside in the evolving understanding of embodied emotion and its management by performers. At every major turning point in the development of theatrical theory and practice, prevailing philosophical theories of the body and mind have set the limit terms for effective expression and hence the criticism that responds to it. Most authorities have presupposed, for instance, with varying emphases but fundamental agreement, that effectiveness means “being there in the moment.” But where is that?

The Science of Presence

I first explored the historically situated psychophysiology of feeling and expression in The Player’s Passion: Studies in the Science of Acting (1985), following up with It (2007). Then Jane Goodall (the Australian theatre historian, not the primatologist) went further, specifying the science behind theories of presence in Stage Presence (2008). More recently, Matthew W. Smith expanded the question to include 19th-century theories of neurological personhood in The Nervous Stage (2017). With our research concentrated on sources from the 18th and 19th centuries, neither Goodall and Roach nor Smith have found recently emerging applications of neuropsychology or cognitive psychology to acting theory particularly helpful. That is mainly because their explanations of neural processes lack the exigency of those produced by the actors and acting theorists of the past who have most profoundly shaped the ideas and practices of modern theatre and drama. What does have exigency is the network of theories advanced by empiricist natural philosophers such as Denis Diderot, Luigi Galvani, Franz Anton Mesmer, George Henry Lewes, Charles Darwin, and Nikola Tesla. Their ideas, including pre-Freudian theories of the unconscious based on the doctrine of nerve “Sensibility” and pre-Derridian conceptions of absence as an electromagnetic force, explicitly informed the authorities who were then asking a deceptively simple question about performance and reception: What physical circumstances make certain people, actors as well as others, especially compelling to watch even when they are apparently doing nothing?

In fact, versions of such a via negativa — exploring the essence of something by saying or doing what it is not — have been in play for millennia. Two cherubim extend their golden wings to create an empty space on the Ark of the Covenant: “In that space,” God says, “I will meet you” (Exodus 25:22). In Ion (330 BCE) Plato has Socrates describe the eponymous rhapsode (elocutionist) as an empty vessel filled at second hand by the muse whose inspiration is transmitted through the medium of the poet and thence to the audience through the ventriloquized performer, drawing them all together like a chain of hollow metal rings suspended from a magnet. (The word ionization in chemistry and physics comes from a Greek verb, not the proper name, but the coincidence is nevertheless suggestive.) Apophatic theology (4th and 5th centuries CE) speaks only of what cannot be said about the divinity of God. In each case, pagan or monotheistic, presence completes a circuit opened by absence.

Correspondingly, influential performance theorists of more recent times have promulgated their own version of such a negative theology of presence. Jerzy Grotowski summarized his methods of actor training as “a via negativa — not a collection of skills but an eradication of blocks” (1968:17). Richard Schechner defined the actor-character relationship by doubling down on a negative: “Olivier is not Hamlet, but also he is not not Hamlet” (1985:123). Eugenio Barba and Nicola Savarese extolled the energizing “virtue of omission” and showed the actor different ways “to perform absences” (1991:174–75). These generative thinkers acknowledge that they, in turn, stand on the shoulders of giants — practitioners who passed on an open secret deeply rooted in the tradition of acting for the stage and ultimately the screen. Zeami, founding master of the Kanze school of noh, quotes what had clearly become a commonplace by the beginning of the 15th century: “when you feel ten in your heart, express seven in your movements” ([1424] 1984:75). Jacques Lecoq teaches the performer a most rigorous technique of self-editing: “beneath the neutral mask the actor’s face disappears” ([1997] 2002:39). Finally, Alfred Hitchcock famously insists on the most ascetic discipline of abnegation imaginable in front of the movie camera: “The chief requisite for an actor is to do nothing well,” he told François Truffaut, “which is by no means as easy as it sounds” (in Comey Reference Comey2002:14).

The crucial turning point for the science of theatrical presence, however, came with the innovative secular metaphysics of the Enlightenment. Here divinity played little part, even if the Aufklärer promulgated replacement mythologies of their own. “Myth is already enlightenment,” argue Adorno and Horkheimer in Dialectic of Enlightenment, “and enlightenment reverts to myth” ([1947] 2002:xviii). One of the most successful of those myths posits that there is an authentic self that lies buried under an outer shell of social artifice. Then called “natural philosophy,” 18th-century science, including the nascent social sciences, rebooted classical rhetoric (Vico [1744] Reference Vico1968), which was founded on ancient medical doctrines, and renovated it by advancing new theories of sensibility, or responsiveness of the sensorium to physical and moral stimuli. Then natural philosophers applied these theories to human behavior in all its forms, including literary productions such as narrative and drama. But it is the natural philosophy of the negative charge, as it was then understood, that most concerns the historical question of presence. Answering that question requires an account of a one-word hypothesis about electricity, magnetism, and oxidation that prevailed during the 18th century, only to be preempted by new paradigms and largely forgotten today except by specialist historians of science: phlogiston.

Phlogiston: The Stuff That Isn’t There

Before there was “oxygen” — named as such in 1777 by Antoine Lavoisier, who showed that it combines chemically with other elements during combustion — there was phlogiston. From about the beginning of the 17th century until toward the end of the 18th, chemists believed that flammable matter contained an element or a property that was emitted, not combined, as fire burned or metal rusted. Based on their empirical observations, Lavoisier’s predecessors believed that this so-called phlogiston, a word they derived from the Greek for “burning up,” acts as the very principle of fire itself. As things turned out, they were proved wrong (or at least superannuated) by what came to be known as the “chemical revolution”; but they were not fools. In the quasi-mythic sweep of its apparent explanatory power in 18th-century chemistry, phlogiston resembles the unconscious (das Unbewusste) in 19th- and 20th-century psychology. Observable only in their effects, they were both hypotheses that addressed the problems presented by a variety of noticeable phenomena. These included, respectively, conflagrations and neuroses. But the crucial import of their coupling as explanatory principles comes from ideas of animal electricity that rest on the hypothetical omnipresence of phlogiston in nature.

Strange at first encounter, this discarded hypothesis actually proves more theoretically user-friendly than current neuroscientific terminology. At least you can still see what looks like phlogiston at work, just as those early chemists thought they did, with your own eyes. Place a glass container over a burning candle. Observe how the flame soon flickers and dies. What you are seeing, according to the best authorities prior to Lavoisier (and contemporaries of actors like Thomas Betterton and David Garrick), is the air in the jar becoming phlogisticated; that is, so saturated with phlogiston that it can’t hold any more. Meanwhile, the matter in the candle is becoming de-phlogisticated, depleted of its supply of phlogiston. When the transfer is complete: Violà! No flame. While you can thus easily see what phlogiston does, you can’t see what phlogiston is. As the very quintessence of flammability, it is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and weightless. Like fire to the ancients, it is an element. Like electromagnetism to the moderns, it is a force. It is the stuff that isn’t there; or, more precisely, the stuff that isn’t there until it disappears in the act of becoming itself.

As natural philosophy incrementally gave way to what we call science, experimenters measured the output of phlogiston and called it by different names, such as heat, light, and electricity. Eighteenth-century kite-flyers knew the latter as “Electrical Fire” (Franklin 1752). Indeed, to Ben Franklin electrical fire existed as a conserved quantity of a single fluid, a surplus of which (in effect, a positive charge) readily filled a deficit (that is, a negative one) in a transfer known as lightning. If this sounds quaint, like powdered wigs and “Purfuit of Happinefs,” you will nevertheless still want to attach your red jumper cable to your car-battery pole marked “+,” unless you want to assume the risk of experiencing electrical fire directly, as Franklin did to prove a point. And as for the transfer of matter into energy, since 1905 science has been working on the implications of the hypothesis that energy equals mass times the constant squared, leading to many wonderful but apparently impractical theories, such as particles without mass (gluons) and the infinitesimally elusive Higgs boson, which isn’t there until it disappears, as well as other, all-too practical applications, such as thermonuclear weapons.

Writing about the stage across all periods, scholar and poet Andrew Sofer has expansively opened up similar conceptual ground in Dark Matter: Invisibility in Drama, Theater, and Performance. Omitting no radiation but exerting much greater gravitational attraction than ordinary matter, dark matter, like phlogiston, is invisible but observable through its effects on everything else. Paraphrasing Schechner’s double negative, Sofer presses home his analogy: “My thesis is simple: invisible phenomena are the dark matter of theater. Materially elusive though phenomenologically inescapable, dark matter is the ‘not there’ yet ‘not not there’ of theater” (2013:4). Concentrating Sofer’s thesis on the Enlightenment yields this conclusion: as absence is to 18th-century science, so it is to 18th-century theatre and its protomodern dramaturgy of invisibility (mask-wearing, violence offstage), silence (tableaux, pantomime), and gestural by-play (unspoken thought).

A key early source that supports the claim of the 18th-century as the period of theatrical experiment and innovation is The Life of Mr. Thomas Betterton, the Late Eminent Tragedian, published by Charles Gildon in 1710 (fig. 1). As the first intellectual biography of an actor, it places Betterton in the tradition of classical rhetoric but also at the center of a burgeoning performance culture, in which actors became exemplars of techniques that persuade, edify, and inspire their contemporaries. Gildon advertises his ambitious program in his subtitle: “Wherein the Action and Utterance of the Stage, Bar, and Pulpit, are distinctly consider’d.” After a dozen pages or so of anecdotes, he proceeds to put in Betterton’s mouth a pastiche of unacknowledged quotations from various previously published rhetorical treatises. What is most significant, however, is Gildon’s confidence in assigning these ideas to the great tragedian based on reported conversations with him (Gildon 1710:18–19). Gildon clearly believed that the likely readers of The Life, those who knew Betterton and saw him perform (he continued to act until a few days before his death in April 1710), would find such descriptions of rhetorical tropes plausibly consistent with techniques they had seen Betterton practice on the stage, since he never mounted a pulpit or practiced law. Like contemporary natural philosophers of electricity, Betterton referred to the transfer of energy between actor and spectator as an arc of fire: “And this Fire of their Eyes will easily strike their Audience, […] and by a strange sympathetic Infection, it will set them on Fire too with the very same Passion” (in Gildon 1710:67). Celebrated for his exceptional ability to command the rapt attention of his audiences by his compelling stage presence (Roberts Reference Roberts2010), Betterton knew whereof he spoke.

Figure 1. Portrait of Mr. Thomas Betterton, face three-quarter, printed opposite the title page of his 1710 biography, The Life of Mr. Thomas Betterton, the late Eminent Tragedian. Print by Michael Vandergucht after Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1710. DYCE.2332. (Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

In Gildon’s Life the rhetorical tropes that pertain to absence comprise a class by themselves. Betterton calls them tropes of “suppression,” and he features the example of aposiopesis (in Gildon 1710:132). Written texts report tropes of suppression by inserting the em-dash, the underscore, or the ellipsis, but for the actor they function like a fermata in musical notation, denoting a pause of indefinite duration. Aposiopesis arises when the “if” clause of a condition is stated without an ensuing “then” clause. The supposed Betterton glosses this trope succinctly and offers advice on how to deliver it with proper expression: “Aposiopesis is a suppressing of what might be further urg’d; and in this the Speaker must lower his Voice a Tone or Two, and pronounce the foregoing Words with the highest Accent” (132). Parents might recognize this trope as the most commonly occurring one in which to deliver an ultimatum without specifying the consequences for noncompliance: “If you don’t pick up your room…” Among Betterton’s most prominent roles, King Lear has recourse to aposiopesis when he curses Goneril and Regan as the stage directions call for “Thunder and Lightning.” Nahum Tate retained these lines verbatim in his 1681 adaptation, which was the version Betterton played:

No, you unnatural Haggs,

I will have such Revenges on you both,

That all the world shall — I will do such things —

What they are yet I know not, but they shall be

The Terrors of the Earth; you think I’ll weep,

This Heart shall break into a thousand pieces

Before I’ll weep — O Gods! I shall go mad.

(1681:Act 2)

By creating a void marked in print by — or _______ or …, which the actor marks with brief silences, tropes of suppression induce the dramatic version of the interaction between positive and negative charges in the production of “Electrical Fire,” completing the thought in the mind of the attentive auditor as quick as lightning.

In the modern theatre, this phenomenon is known as “subtext.” It elevates the implicit over the explicit, connotation over denotation, and phatic meanings over ideational or referential ones. Its emergence in the 18th century is documentable both in all those punctuation marks that signify absence and also by eyewitness accounts of tropes of suppression executed in performance. So the philosophe Denis Diderot asks, “What is it that affects us in the spectacle of a man fired by some great passion? Is it his words?” And he answers his own question: “Sometimes. But what is always moving are cries, inarticulate words, moments when speech breaks down, when a few monosyllables escape at intervals, a strange murmuring from the throat or from between the teeth” ([1757] 1994:21). If that seems to describe Marlon Brando, the connection is not coincidental. This evolving style, the collective work of two centuries, was the contribution of actors and actresses who repurposed the rhetorical tropology of suppression into a technique of sharing what appeared to be the most authentic inner workings of their minds by sustaining the most stringently selective exterior economy of their bodily expressive means.

No actor in the theatrical history of any nation was more celebrated or better remembered for his stage presence than David Garrick was in 18th-century Britain. Making his sensational debut as Richard III in 1741, he posed in the role for William Hogarth in 1745 (fig. 2). Hogarth’s great painting makes a bid for elevating portraiture to the prestige of history painting, but it also records a significant moment in the development of modern acting style. Garrick startled his audiences with his striking physical transitions between emotions and abrupt changes of cadences in speaking Shakespeare’s verse, making “points” by pausing for emphasis at surprising places and inserting dashes, as it were, out loud (Harriman-Smith Reference Harriman-Smith2021). A partial record of his innovative reading of King Richard’s lines may be inferred from the punctuation of the printed text. Contemporary grammarian Joseph Robertson glosses a specific example in his Essay on Punctuation ([1785] 1969): Richard’s desperate order to his remaining loyal bowmen to fire their arrows at the foes who close in around him on Bosworth Field. To the exhortation, “Draw archers, draw, your arrows to the head,” Garrick adds a dash that is neither in Colley Cibber’s adaptation of 1700 nor in either of the Shakespearean versions (Q1 1597 or F1 1623). Deploring the misuse of the dash elsewhere, Robertson commends Garrick for this histrionic emendation: “The dash is frequently used by hasty and incoherent writers, in a very capricious and arbitrary manner, instead of the arbitrary point. The proper use of it is, where the sentence breaks off abruptly; where the sense is suspended; where a significant pause is required; or where there is an unexpected turn in the sentiment.” Garrick found just such a crux, and Robertson renders the line as he heard it, followed by a comment:

Figure 2. Detail of David Garrick as Richard III, 1745 (oil on canvas), by William Hogarth (1697–1764). (Courtesy National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery)

DRAW, archers! draw! — your arrows to the head!

The latter part of this line is an afterthought. Garrick used to pause very properly, where the dash is inserted. The ardor and impetuosity of Richard are more naturally and forcibly expressed, by this division of the sentence, than by the regular pronunciation of the words in their grammatical connection. ([1785] 1969:129, 131)

Here the actor rewrites the text by creating subtext, dramatizing Richard’s petulant reiteration of his order by a pause during which the point is that nothing happens: the demoralized archers do not shoot, finally compelling the embattled and exasperated king to humiliate himself by coaching them down to the last motion, creating “an afterthought” by adding a meaningful absence, the delivery of which onstage the compositors and grammarians represented typographically with a dash.

Richard’s trope of suppression in his command to the archers was preceded and foreshadowed by the more profound one captured by Hogarth. Ghost-ridden Richard starts from his troubled sleep on the eve of battle, as his bravado has deserted him along with many of his soldiers. Hogarth’s painting captures Garrick’s embodiment of the complexity of divided consciousness as the bloody tyrant awakes in wide-eyed horror from the nightmare he has been dreaming into the nightmare he is living. But the effect of this galvanic moment of histrionic presence depends on the actor’s performance of an absence by honoring the dash with silence and stillness, during which King Richard must not blink.

The psychological counterpart to the chemical theory of phlogiston was the as-yet-unnamed forerunner of what the 19th century identified as the unconscious (Whyte Reference Whyte1960). Here the stuff that isn’t there (in consciousness) acts dynamically on what is, creating something for the ages out of nothing you can put your finger on. When Diderot speaks of great actors, he usually has David Garrick in mind, even when he speaks in the plural; and in his homage to Garrick in “The Paradox of the Actor” he identifies the source of actors’ creativity in their capacity to convert that which is “formed inside of them, without their realizing it” into a kinetic spectacle ([1778] 1994:106). Diderot may have borrowed this formulation of unconsciousness from his probing conversations with Garrick during the actor’s visit to Paris in 1764–65. Or Garrick may have gleaned it from Diderot.

At any rate, in his written critique of La Clairon, the French tragedienne (fig. 3), penned in 1769, Garrick begins with an allusion to vivisection, the method then preferred for investigating the physical basis for life’s invisible processes:

Figure 3. Portrait of French actress Mademoiselle Clairon, bust-length, turned to right, in oval frame supported by two dragons; in the lower part, a drapery on which is represented a scene from Medea. 1767. By Jean Baptiste Michel. (Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum)

Your desection of her, is as accurate as if you had opened her alive; She has everything that Art and a good understanding, with great Natural Spirit, can give her — But then I fear (and I only tell you my fears, and open my Soul to you) the Heart has none of those instantaneous feelings, that Life blood, that keen Sensibility, that bursts at once from Genius, and like Electrical Fire shoots thro’ the Veins, Marrow, Bones and all, of every Spectator. ([1769] 1963:letter 635)

The reference to the “Electrical Fire” that Clairon lacks clearly places Garrick’s comments in the context provided by contemporary investigations into the nature of electricity, which Luigi Galvani was then applying to nerve physiology in animals (Marie Reference Marie2019:241–46). Galvani discovered that the contractions in the long muscle of a prepared frog could be triggered at a distance by sparks from a static electricity machine or even by flashes of lightning in the atmosphere (fig. 4). Garrick had already noted that phenomenon in the uncanny conductivity occurring between certain actors and their audiences.

Figure 4. Galvani’s experiments on the sciatic nerve of frogs; first detection of galvanic currents. Sciatic nerve, Galvani. Bologna: Per le stampe del Sassi, 1797. (Courtesy of Creative Commons)

Garrick dissects Clairon in search of an invisible, weightless property or force, one that emanates from within her, having abided there as a potential unknown to her, and which disappears instantaneously as a condition of its appearance in the perceptions of her audiences. He continues his investigation with a brief look into the abyss of the unconscious origins of affective behavior. What he probes could not be explained in terms of the prevailing Cartesian dualism of conscious thought and insensate machine. Garrick therefore hypothesizes processes of the mind that escape detection by introspection or memory. He writes: “Madam Clairon is so conscious of what she can do, that she never (I believe) had the feelings of the instant come upon her unexpectedly. — but I pronounce that the greatest strokes of Genius, have been unknown to the Actor himself, ’till Circumstances, and the warmth of the Scene has sprung a Mine as it were, as much to his own Surprize, as that of the Audience — ” ([1769] 1963:635). To spring a mine means to ignite an explosive charge buried deep beneath the ground. In the military engineering of the period, mines were set off without warning in order to surprise the defenders under whose fortifications they had been surreptitiously placed. Such a “Surprize” is not an occult phenomenon — anyone who has ever spent time in a rehearsal room has seen it happen (Goebbels Reference Goebbels2015). As Constantin Stanislavski cautioned in his paradigmatic textbook An Actor Prepares: “The unexpected is often the most effective lever in creative work” (1936:156).

Each of the aforementioned hypotheses — phlogiston as electrical fire or the unconscious as inaccessible potential — represents a historically contingent category for the investigation of a longstanding problem in philosophy and science: phlogiston, the relationship of matter and energy; the unconscious, the relationship of matter and mind. The hypothesis of phlogiston arose to prominence when the understanding of fire as simply one element among four (the others being earth, air, and water) became scandalously inadequate but before the discovery of oxygen redefined it as rapid oxidation in the exothermic chemistry of combustion. The hypothesis of the unconscious arose to prominence when the Cartesian dualism of ghost and machine became scandalously inadequate but before cognitive neuroscience redefined it as subconscious data-processing by specialized neurons localized in the basal ganglia and cerebellum. In retrospect what the two older hypotheses have most in common is that they are likely to remind you — like the other absences in your life, such as those caused by loss, grief, or traumatic alienation — of the ambient presence exerted every day by all the stuff that isn’t there on whatever you still have left that is.

Conclusion: In Camera

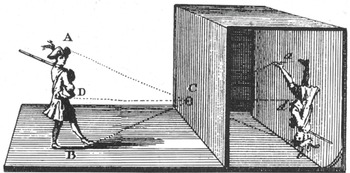

The word camera derives from the Latin for “room” or “chamber,” a usage that still obtains today in law when judges hold proceedings in camera, meaning in their chambers instead of open court. Evidence presented in camera is either declared admissible and brought to light for presentation to the jury or rendered inadmissible and suppressed. The early-modern invention of the camera obscura (fig. 5) presaged photography by passing an image through a lens and projecting it on the wall of a darkened chamber.

Figure 5. Illustration of the camera obscura principle, circa 18th century. Unknown author. (Courtesy of Creative Commons)

The first photographic cameras similarly functioned as black boxes in which the photographer exposed photosensitive chemicals on treated plates (and later on celluloid stock for motion pictures) by admitting light in varying intensities and durations. Skilled application of chemical processes developed the image from its negative. Now all of that happens digitally, but the process starts with what comes into the black box. Actors had techniques of developing positive presences from negatives long before the invention of photography. In her account of 18th-century actors’ autobiographies, Julia Fawcett shows how performers like Colley Cibber created exaggerated public personae to misdirect audiences from their private lives or their lack thereof. In the case of actress-poetess Mary Robinson, for instance, the “conspicuous absence” of her persona, Fawcett argues, “invites the reader to fill in its blanks and thus transforms the reader from critic to collaborator” (2016:5). Into an empty space misrepresented as secrets, readers or spectators project their own imaginings and misconstrue them as expressions. Animated by such unconscious collaboration, therefore, the neutral mask can make an astonishing variety of faces.

The ubiquity of the camera in the 20th and 21st centuries has vastly expanded the horizon of reception for what was once the professional actor’s work. Now it has completely run amok all across a networked “surveillance society” epitomized publicly by CCTV (Morrison Reference Morrison2016:73–75) and privately by Zoom. When “working from home,” “meeting online,” or “saying a final goodbye,” you are in the camera, and the camera is in you, much as the fish is in the water, and the water is in the fish. But now no jurist impartially rules on the admissibility of your data, so you have to suppress yourself as best you can. Your artful presence in character, like Olivier’s Hamlet — not You but not not You — is the increasingly desperate role of a lifetime, because when algorithmic tracking backed by artificial intelligence directs the camera’s eye, it sees whatever it wants.