Introduction: A new form of work, a new standard of justice?

Since 2011, when the concept of ‘Industry 4.0’ was introduced at the German Hannover Trade Show (Reference Kagermann, Lukas and WahlsterKagermann et al., 2011), the discourse on the digital transformation of work has been dominated by the notion of ‘4.0’ (Reference PfeifferPfeiffer, 2017). While ‘Industry 4.0’ refers to particular models of production and four associated technological leaps (from the steam engine to electrification, the information age, and today’s cyber-physical systems), Germany’s Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs has coined the term ‘Arbeit 4.0’ (BMAS, 2015: 34–35) to refer to the transformation of the forms and institutions of work. The four stages in question here are: (1.0) the emergence of industrial society and early workers’ associations at the end of the eighteenth century, (2.0) the beginnings of mass production and the welfare state, (3.0) globalisation and the development of the social market economy, and (4.0) Internet-based work and the associated social compromises and value shifts. Stages 1.0 to 3.0 were marked by the institution of gainful employment; even today, paid work is primarily carried out by employees with permanent employment contracts within a physical (commercial) organisation. All forms of social security (whether for accidents, unemployment, or retirement) – ultimately the institution of the welfare state as such – depend to a great extent on this model of employment.

Crowdworking nonetheless breaks with this model: like most platform-orchestrated models of work organisation, crowdworking often bypasses employment regulations and thus undermines traditional labour (Reference MinterMinter, 2017). Crowdworking is understood here as a paid form of crowdsourcing and thus as a ‘new principle of the organisation of work: here work is no longer individually assigned via the right of instruction; workers rather choose their work themselves’ (Reference Mrass, Leimeister, Fortmann and KolocekMrass and Leimeister, 2018: 139). With this form of work, characteristics of work seem to be returning that were once thought to have been relegated to capitalism’s past after the rise of the ‘standard employment relationship’ in the 20th century (Reference StanfordStanford, 2017). Unlike outsourcing, in which tasks that were previously performed internally are assigned to other companies in large bundles on the basis of fixed service contracts, crowdsourcing consists in offering individual and often piecemeal tasks to a mass of unknown actors through open calls on intermediary Internet platforms. There is no direct and long-term contractual relationship between the labour provider and the labour user – on the contrary, the highly flexible and selective relationship between the two parties, mediated by a competitive platform, has been hailed as a ‘new template of work’ (Reference BollierBollier, 2011: 14). The number of crowdworkers in Germany today remains relatively low (Reference Huws, Spencer and SyrdalHuws et al., 2017; Reference Pongratz and BormannPongratz and Bormann, 2017), yet if crowdworking were to become the predominant model of work and self-employment is to increasingly displace other, more traditional kinds of workers, this would have enormous consequences for all of the institutional systems associated with the labour market and the welfare state. Even if the end of contractual employment is not yet in sight, there already seems to be a need for regulation in the crowdworking sector. Both internationally (Reference BergBerg, 2016; Reference Graham, Hjorth and LehdonvirtaGraham et al., 2017; Reference Mandl, Curtarelli, Meil and KirovMandl and Curtarelli, 2017) and in Germany, there has been much discussion of the necessity of such regulation (Reference BennerBenner, 2014; Reference Dabrowski and WolfDabrowski and Wolf, 2017), focusing particularly on labour laws, data protection, codetermination practices, income security, and worker protection (Reference Stewart and StanfordStewart and Stanford, 2017).

In 2017, one of the eight crowdworking platforms based in Germany signed a code of conduct intended to serve as a ‘guideline for a profitable and fair collaboration between crowdsourcing firms and crowdworkers’ (Deutscher Crowdsourcing Verband, 2017). Crucially, the code of conduct stipulates that workers should be paid fairly. Yet what do crowdworkers in Germany consider just? Are their expectations different from those of employees in traditional, regulated employment? And do these expectations change in areas where their performance cannot be compared with traditional employees, since the work they perform is not also undertaken within (commercial) organisations? This article pursues these questions concerning perceptions of justice in the crowdworking sector. To this end, it first discusses the current state of research on crowdwork and performance-related justice in Germany and then presents the results of our own qualitative and quantitative surveys of crowdworkers using different types of crowdwork platforms in German-speaking countries.

Crowdwork: Work outside of firms and employment contracts

Crowdwork can be defined in general as: ‘[…] the strategy of outsourcing a job that would normally be performed by an employee to an organisation or private person via an open call to a mass of unknown actors’ (Reference PapsdorfPapsdorf, 2009: 69). As Reference Hertwig and PapsdorfHertwig and Papsdorf (2017: 526) have argued, crowdwork exhibits ‘only partial overlaps’ with the sharing economy. In the literature, various attempts have been made to give a typology of the various forms of crowdwork. Reference Mrass, Leimeister, Fortmann and KolocekMrass and Leimeister (2018), for instance, distinguish between seven different platform types: Context/text creation platforms, design platforms, innovation platforms, marketplace platforms, microtask platforms, testing platforms, and customer service/market research/sales platforms (p. 142). Alongside platform type, other commentators have introduced additional classificatory criteria, such as labour force pool, contract type, form of algorithmic control, and sources and mechanisms of establishing ‘digital trust’ (Reference Howcroft and Bergvall-KårebornHowcroft and Bergvall-Kåreborn, 2019). The authors essentially distinguish between four platform types on the basis of two criteria: whether the work is reliably paid (i.e. paid vs non-paid or speculative work), and whether the worker (such as a specialist freelancer) or the client is to be considered the initiating actor. A classification undertaken on the basis of qualitative expert interviews in German-speaking countries, meanwhile, distinguished four key platform types: innovation platforms, testing platforms, microjob platforms, and design platforms (Reference KawalecKawalec, 2019).

The difficulty of giving a clear definition of crowdworking makes it hard to assess how widespread the practice is, particularly if we wish to quantify this global phenomenon for the German context. In contrast to the USA, the economic significance of crowdworking platforms in Germany remains low. At the beginning of 2017, 32 crowdworking platforms either had their headquarters or at least one (physical) branch in Germany (Reference Mrass, Leimeister, Fortmann and KolocekMrass and Leimeister, 2018: 142). On the global scale, ‘both supply and demand are relatively low’ in Germany (Reference Pongratz and BormannPongratz and Bormann, 2017: 165).

The crowdworking platforms themselves do not provide reliable figures on the number of active crowdworkers using their systems; they either treat these figures as trade secrets or advertise their services on the back of figures that are likely exaggerated. We can also assume that many crowdworkers are active on more than one platform, so that any attempt to quantify the total number of crowdworkers in Germany or German-speaking countries using such figures would be of limited value, even assuming a greater level of transparency on the part of the platforms. Two studies have nonetheless attempted to produce as comprehensible and reliable an estimate as possible of the statistical significance of crowdworkers in Germany or German-speaking countries:

• On the basis of a representative online survey (N = 2180), a comparative study by Reference Huws, Spencer and SyrdalHuws et al. (2017) estimates that 1.45 million or 2.5% of working-age Germans earn at least 50% of their income from crowdworking. On the basis of a narrower definition, the study also identifies a ‘core group’ of crowdworkers consisting of those who also use a special app to stay informed of job offers. The study estimates that circa 1.07 million of these ‘professional’ crowdworkers live in Germany, which equates to 1.9% of the working-age population

• In their own study, Reference Pongratz and BormannPongratz and Bormann (2017) proceed more carefully and criticise the Huws et al. study as ‘misleading’ (p. 180) on methodological grounds. They estimate that 500,000 to a million people have set up a profile (that still exists) on a platform for online working in Germany in the last 10 years. Of these, 100,000–300,000 take on at least one job per month, while only 1000–5000 people earn a secure income from this work (in comparison with the average German wage (Reference Pongratz and BormannPongratz and Bormann, 2017: 167).

Crowdwork can certainly be advantageous for workers, particularly in regions with a poorly developed labour market. This was affirmed by a long-term study on crowdwork in Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia, which stated that ‘There is no simple story of exploitation […]’ (Reference Graham, Hjorth and LehdonvirtaGraham et al., 2017: 153). Nevertheless, the study also shows that the risks of this working model increase as more workers depend on it to earn a living. Similarly, a study on platform operators in Germany (Reference Mrass, Leimeister, Fortmann and KolocekMrass and Leimeister, 2018: 145–148) has shown that crowdworkers can benefit from greater working flexibility and from an additional source of income, but have to cope with relatively low pay, a lack of social security benefits, and income fluctuations. Crowdsourcers, on the other hand, not only benefit from greater flexibility and external expertise; they can also reduce their outgoings and save on social security contributions.

New forms of digital work thus seem to resurrect the ‘old’ conflicts of interest over income levels and income security evident in in traditional labour-market institutions and negotiation processes. Where crowdworking is concerned, the lack of regulation is a systemic rather than an accidental feature of the sector, or so to speak: a feature, not a bug. For unlike other forms of platform-mediated work that are undertaken in the real world, purely online crowdwork is characterised by the ‘de-territorialisation’ and ‘de-personalisation’ of work (Reference Menz, Tomazic, Dabrowski and WolfMenz and Tomazic, 2017: 14–15). On the one hand, this has an impact on distributive performance-related justice, since it serves to uncouple the global wage differential from local living costs. On the other hand, it affects procedural performance-related justice, since it leads to a lack of transparency in the relevant evaluation criteria and the possibility of workers influencing these, while also removing the social context provided by the (commercial) organisation. For crowdworkers, the consequences of these changes are of emotional quality (Reference Petriglier, Ashford and WrzesniewskiPetriglier et al., 2018).

Performance and the perception of injustice in the workplace

Reference DubetDubet’s (2008) qualitative study served to renew scholarly interest in the question of worker perceptions of injustice in the workplace, which he conceptualised as ‘normative activity’ in the dual sense of the ‘totality of principles that are considered legitimate’ and the ‘autonomous decision of an independent judgement’ (Reference DubetDubet, 2008: 17). On the basis of 350 interviews, Dubet argued that three basic principles underlie workers’ perceptions of injustice: equality, performance, and autonomy. For crowdworkers, the principles of equality and autonomy are less relevant, because crowdworkers have no possibility to compare themselves with other workers and are per definition fully autonomous. For this reason, we focus on performance. Performance-related justice means that one receives a just reward for work performed (Reference DubetDubet, 2008: 24). For Dubet, the concept of performance encompasses both ‘the objective result of the action’ and the ‘engagement on the part of the author of this action’. The ‘ambivalence of performance’ thus continually oscillates ‘between objective usefulness and effort expended’ (Reference DubetDubet, 2008: 127). Building on Dubet, two large qualitative studies were conducted in the last few years on justice expectations among employees in Germany.

• Reference Hürtgen and VoswinkelHürtgen and Voswinkel (2014) carried out 42 biographical interviews with a cohort composed of ‘average’ employees, that is, middle-aged workers with permanent employment contracts and mid-level qualifications (Reference Hürtgen and VoswinkelHürtgen and Voswinkel, 2014: 39–40). In the interviews, the workers expressed ‘values of universal normative force’ on the basis of fundamental conceptions of themselves as human beings and social beings with a productive capacity. From the perspective of their productive capacity, their income-related expectations were articulated in terms of adequate remuneration for their efforts (Reference Hürtgen and VoswinkelHürtgen and Voswinkel, 2014: 139–140). From the perspective of their social existence, a good income was seen as one that ‘fit’ their lifestyle and their expectations concerning planning security and their rightful social security benefits and pension provision (Reference Hürtgen and VoswinkelHürtgen and Voswinkel, 2014: 145–150). In general, income was conceived both ‘as a reward for an […] accomplishment’ and as a ‘symbolic recognition of one’s productive capacity’ (Reference Hürtgen and VoswinkelHürtgen and Voswinkel, 2014: 149).

• Another sociological study (Reference Kratzer, Menz and TulliusKratzer et al., 2015; similarly Reference Tullius and WolfTullius and Wolf, 2016) examined various forms of the legitimation of work on the basis of 320 qualitative interviews with non-managerial employees in Germany. As well as expecting opportunities for self-realisation in the workplace, involvement in decisions in their immediate working environment, and working conditions that upheld their dignity, the interviewees also expressed subjective expectations concerning performance-related justice as an effort-centred concept. The authors interpret the employees’ normative expectations, which are ‘explicitly or implicitly formulated in the context of particular organisational regulations (such as distributive rules, decision-making procedures, and crisis management measures)’ as demands for legitimacy (Reference Kratzer, Menz and TulliusKratzer et al., 2015: 14). Among skilled workers, the measure of performance-related justice is linked here to a notion of exertion in the workplace, and among ‘knowledge workers’ to a readiness to exert oneself (Kratzer et al., 2015: 50–51).

Alongside these qualitative studies, which illuminate the complexity of the various expectations placed on work, a quantitative study (Reference SchneiderSchneider, 2018) has shown on the basis of the German Socioeconomic Panel (SOEP) that the majority of traditional employees in Germany feel they are fairly paid. Around 61% of workers (64% including those covered by collective bargaining agreements) consider their gross earnings fair, though only 55% (56% including those covered by collective bargaining agreements) consider their net earnings fair. Among almost all groups, gross earnings were considered fairer than net earnings. Interestingly, only 59% of full-time employees consider their gross earnings fair, compared with 62% of part-time employees and 79% of casually employed workers (Schneider, 2018: 366).

Even among those performing ‘mini-jobs’ which like crowdworking jobs are often considered an additional source of income but are usually low paid, provide little to no social security protection and involve zero-hour contracts, 77% of employees consider a good income important or very important, while 82% feel that an income that is fair with respect to their performance is likewise important or very important (Reference BeckmannBeckmann, 2019: 251–342). In both of these respects, the 2016 found a poor match between employees’ expectations and reality: this match was only 47% for a good income and 48% for a fair performance-related income (Reference BeckmannBeckmann, 2019: 293).

Such a results-based orientation is by no means restricted to the crowdworking sector; in more traditional employment relationships, performance-related policies have increasingly shifted from an effort-oriented approach to a results-based approach in recent years (Reference BreisigBreisig, 2018). As Menz and Niess (2017) note, this shift in managerial approach from effort to results is not considered ‘fundamentally illegitimate’ by employees, yet neither does it constitute ‘an independent principle of justice (p. 133; see footnote 12). What is unique to crowdwork, however, is that in contrast to the types of work (including ‘mini-jobs’) considered by the studies noted above, it does not take place within (commercial) organisations. It is nonetheless within such organisations that the ‘question of the formation of this principle’ (Reference Menz, Nies, Behrmann, Eckert and GefkenMenz and Nies, 2018: 132–133) is addressed and that the demand for performance-related justice persists as an ‘enduring source of conflict and critique’ due to its repeated infringement (Reference Tullius and WolfTullius and Wolf, 2016: 496–497). Because this organisational context (and the attendant space for conflict and critique) is lacking in the case of crowdwork, we do not know what to expect regarding crowdworkers’ perceptions of injustice related to their work performance. In the following two sections, we pursue this question empirically. We first present the results of a qualitative study of perceptions of performance-related justice. We used the results of this study to generate items for a survey instrument used in a quantitative study, described in the subsequent section, of attitudes towards performance-related justice among crowdworkers.

Understanding justice and crowdwork: Methodological approach

Whether the results of prior studies on performance-related justice among traditional employees and commercial organisations can also be applied to crowdworkers is an open question. For exploring this question and gaining information on aspects of performance-related justice from the various perspectives of those involved, we undertook our own empirical investigation in two stages. The first stage, detailed in this section, was qualitative and explorative.

Qualitative sample and data

The study (cf. Reference KawalecKawalec, 2019) encompassed 18 interviews with persons engaged in or knowledgeable about crowdworking. Due to the current lack of information about which aspects of crowdwork are typical or dominant, the goal of case selection was to capture a sample of individuals with different kinds of experience with crowdwork for the purpose of generating questions for a quantitative survey. To this end, 11 semi-structured, qualitative interviews were conducted with staff at a large company in the process of shifting some of its operations to crowdsourcing. Also, 18 crowdworkers were interviewed. Three of these crowdworkers were active on testing platforms, seven on innovation platforms, three on design platforms, and five on micro-job platforms. In addition, seven expert interviews (Reference Gläser and LaudelGläser and Laudel, 2010) were conducted with academic and political experts and platform operators. Sampling and analysis were carried out on the basis of grounded theory (Reference Glaser and StraussGlaser and Strauss, 2009). Interviews were semi-structured, allowing for open-ended responses. Inclusion of new interviewees was stopped as the amount of new information from additional cases approached zero. Interviews were transcribed and the content coded using the software MAXQDA with the goal of identifying concepts and concept-categories commonly mentioned by interviewees. Potential interview partners were selected using digital social networks in combination with snowball sampling, by which interview partners were asked to identify other potential study participants (Reference Przyborski and Wohlrab-SahrPrzyborski and Wohlrab-Sahr, 2010). Data collection took place between 2016 and 2018. All participants lived in German-speaking countries.

Quantitative online survey: Item and research design

The qualitative study showed that the themes of planning security, performance evaluations, task descriptions and remuneration are central to crowdworkers’ experiences and expectations about fairness at work. We employed these themes in the development of items for the quantitative survey as described below.

We drew items from two recent studies that addressed the income-specific dimensions of performance-related justice in the crowdwork sector (Reference Alpar and OsterbrinkAlpar and Osterbrink, 2018; Reference Ye, You and RobertYe et al., 2017). These studies not only asked crowdworkers about ‘perceived fairness in pay’ (PFP); they also linked this question to specially devised tests on microtask platforms such as MTurk. In doing so, they observed a link between PFP and performance quality (Reference Ye, You and RobertYe et al., 2017: 333).

The authors formulated three items on PFP for crowdwork: (1) ‘My payment reflects the effort I have put into the task’, (2) ‘My payment is appropriate for the work I have completed’, and (3) ‘My payment is justified given my performance’ (p. 330). These items had been in turn adapted from Reference ColquittColquitt’s (2001) organisational justice scale (GEO), which was applied to the German context and validated by Reference Maier, Streicher and JonasMaier et al. (2007).

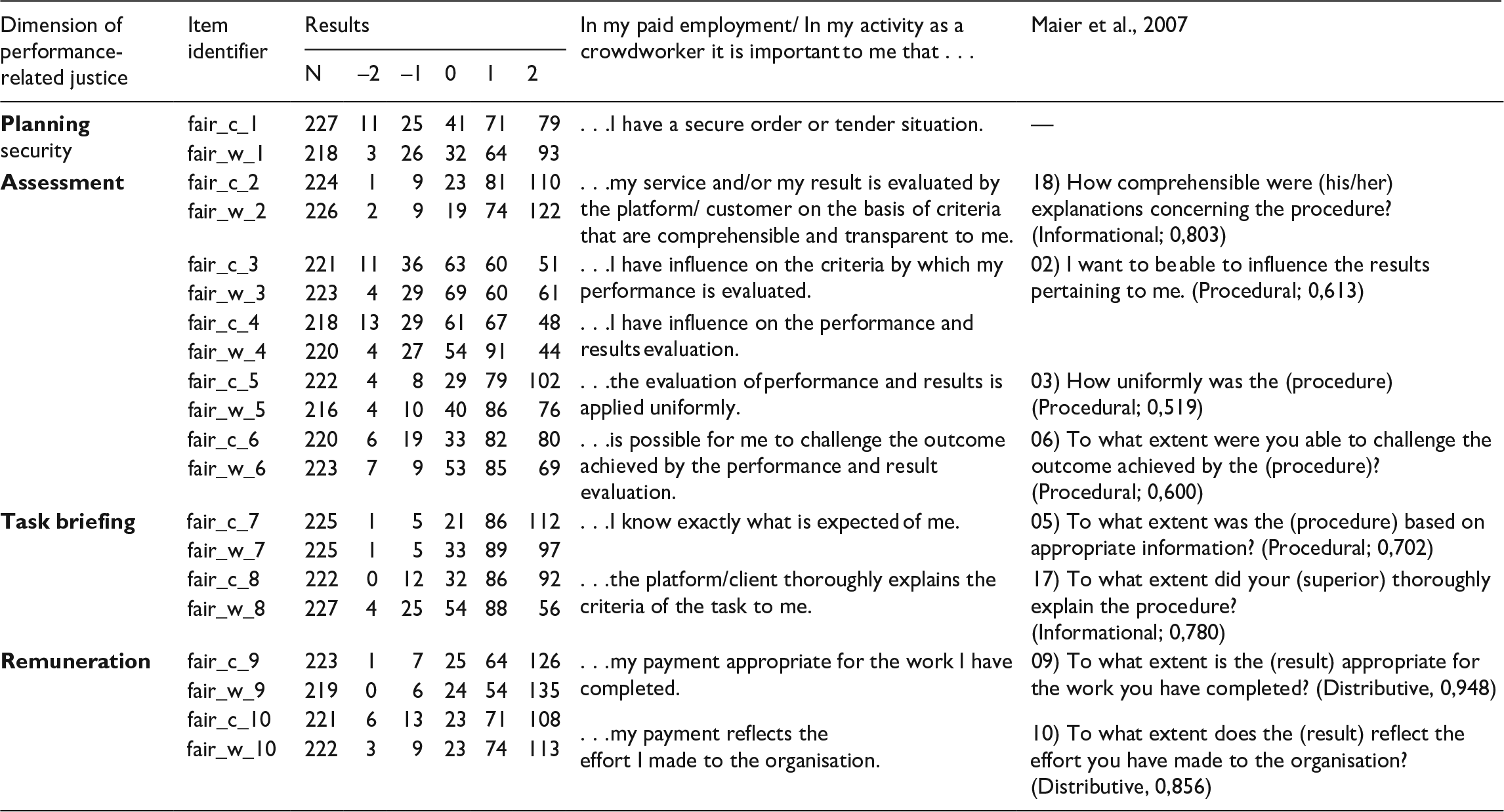

The GEO comprises four scales concerned, respectively, with procedural justice (7 items), distributive justice (4 items), interpersonal justice (4 items) and informational justice (5 items), with a Likert-type scale running from 1 (not at all or almost never) to 5 (completely or often; Maier et al., 2007: 101). The authors emphasise that the way in which the survey is explained to interviewees and some item formulations can be changed to fit new research questions (Maier et al., 2007). For incorporating the qualitative results presented above, we thus adopted the various dimensions of the GEO as follows for our data collection ( Table 1A in the appendix shows the formulation of the items and how these differ from those of Reference Maier, Streicher and JonasMaier et al. (2007). Our changes were made necessary by the following considerations:

• Since crowdwork does not involve any contact with superiors, the dimension of interpersonal justice does not apply

• Procedural justice is concerned with decision-making processes (in our case, those involved in setting and evaluating tasks) and the extent to which they are seen as capable of being influenced. Three procedural items provided the basis for four items assessing the dimension of performance evaluation, and a further procedural item inspired the formulation of an item on the dimension of task descriptions

• In Reference Maier, Streicher and JonasMaier et al. (2007), informational justice refers to the information-specific behaviour of decision makers (e.g. whether such individuals are truthful or provide information in a timely manner). In our context, however, it refers to platform-mediated processes. Two items were used to assess the dimensions of performance evaluation and task description.

• Distributive justice is concerned primarily with the fairness of the relationship between an individual’s contribution (the quality and quantity of his or her work) and the revenue earned from it. Two distributive GEO items inspired the two items on the dimension of remuneration.

For recruiting study participants, we approached crowdworkers on three German-language online platforms for testing, innovation and design or micro-jobs. We used the platforms themselves for finding participants and conducted the survey using Unipark (now: Questback).

Survey sample: Descriptive characteristics

A total of 230 crowdworkers responded to the survey (testing, innovation and design N = 121 and miscellaneous micro-jobs N = 99). Almost equal numbers of the participants identified as female (47.4%) and male (52.6%). The average age was 39.1 years (N = 227; SD = 12.6), with the youngest participant reporting an age of 19 and the oldest 73. The majority of the participants (62.5%) stated they had completed an academic degree (26.6% have a degree from a university of applied sciences and 35.8% from a university), while 37.6% report to have a vocational profession. Likewise, over 47.2% stated that they were employed full-time, 16.6% part-time. In all, 17.9% describe themselves as unemployed, and a further 18.3% work in mini-jobs or are currently in training measures. Participants on average work on 1.7 platforms (N = 224; SD = 0.909), the maximum is five platforms, but the majority of 54.9% concentrates on just one platform. Per month the average working hours on platform is reported with 48.4 hours (N = 215; SD = 58.341 with a maximum of 392 hours per month). Instead of doing platform tasks on the road or within regular employment, 94.4% of our sample do their crowdwork at home.

On average, respondents work 40 hours (N = 216) a month on platforms, with 8.8% working 100 or more hours a month and one reported a high of 392 hours. Our sample did not differ significantly from those of other studies on crowdwork. Reference Huws, Spencer and SyrdalHuws et al. (2017) estimated on the basis of their sample that 61% of crowdworkers in Germany are male and 39% are female, while 52% are aged between 16 and 35% and 63% are in full-time employment. According to Reference Pongratz and BormannPongratz and Bormann (2017), too, the majority of crowdworkers are university-educated and under 30 years old. Depending on the study quoted, the percentage of male workers in the sector is between 50% and 68% (p. 168). Footnote 1

Qualitative findings: Understanding justice expectations

Extrapolating from the crowdworker interviews, we mapped four areas of crowdwork in which expectations were articulated regarding performance-related justice. One central area is planning security. Crowd workers can never be sure how many jobs they will receive and whether they will ultimately be paid for them, and this lack of security is a frequently raised issue, one that is only mitigated when crowdwork is undertaken as an additional source of income rather than as the main source of income. The following represent two typical responses on this point:

The disadvantages are that you can’t really count on a fixed salary. I mean, I can’t say: at the end of the month I’ll always get my fixed salary, my however-many euros – you just can’t rely on it. (‘Bastian Buchmann’, Testing Platform, 11: 101) Footnote 2

You work on something. You put time into it […]. And then it turns out it’s not been used, then you’ve worked for nothing. […] – yeah, you work and often you do a lot of work and good work and you get nothing for it. And then it just doesn’t work. Then the whole house of cards kind of comes down. (‘Norman Neuland’, Design Platform, 17: 18)

The issue of planning security is closely tied to the fairness of performance evaluations. On this point, the interviewees complain that there is a lack of transparency in the evaluation criteria, and that they do not have the possibility of influencing or raising objections to these or the evaluation process itself. Attempts to raise such objections can come up against quite straightforward barriers, as in the following example:

You don’t know them. You also can’t argue with them. You can let them know via support […] But for these small amounts that you get, really? So for this one euro payment should I send another email to them […?]. And then I say to myself, ‘ah, no, I’ll just get on with the next job instead’. (‘Melissa Müller’, Design Platform, 22: 45)

A further problematic area is the evaluation history, which can lead to the accumulation of injustices in the evaluation process:

It’s only that, when you have a certain number of rejections, you might not be able to access certain jobs. There it just says: only if you have a 90% score in that category or from that client, then you can proceed. And if you don’t have that, then for […] a few weeks, a few months, however long, you’re blocked and can’t do anything else. (‘Klaus Klein’, Microtask Platform, 21: 80)

Crowdworkers not only experience a sense of injustice in relation to their evaluations, however. They also experience it in the lack of clarity in their task descriptions. Gerda Grass, for instance, states that the tasks are often ‘a bit too unspecific’ or ‘wishy-washy’ (Design Platform, 16: 64). Since the task descriptions ultimately affect whether crowdworkers are paid or not, ambiguous or contradictory descriptions are not only frustrating for workers; they also affect their broader sense of fairness. The following represents a typical example:

So, I wrote to them, ‘If you are going to give us briefs, then they have to be clear. That time it was about example sentences. […] At the top it said: ‘You need to give at least two example sentences’, but further down it said: ‘One example sentence is mandatory. Two would be good’. (‘Martin Mönch’, Microtask Platform, 24: 46)

Regardless of the platform in question, the interviewees all find the level of remuneration inadequate. Some compare their potential earnings with other forms of secondary employment, e.g. ‘There I’ve earned two, three euros so far. It’s not worth it. The time you spend on it, you’d be better off mowing lawns’ (‘Pawel Polanski’, Microtask Platform, 14: 22). Others compare the low potential earnings with the profits of the clients and platform operators, e.g. ‘The whole thing is a multi-million Euro business […] it’s a form of modern slavery’ (‘Fritz Freudig’, Innovation Platform, 15: 45). Many interviewees also complain that the pay for the work does not match the effort required, as in the following case: ‘You do a great deal for little pay, and maybe for no pay at all. So that’s a form of exploitation’ (‘Sigmund Schlecht’, Ideas Platform, 19: 41). Note that the crowdworkers interviewed did not feel the lack of social insurance benefits to be problematic, a finding that seems puzzling. However, the interviewees worked in German-speaking countries, all of which have low unemployment and high social welfare benefits independent of employment status. Thus, these crowdworkers are not dependent on their crowdwork gigs for securing health insurance or retirement benefits.

Quantitative findings: Measuring justice expectations

Before presenting the quantitative findings, it is important to understand the limits of our research methods. We collected data on a battery of 28 attitudinal items using a five-point Likert-type scale ((-2) = strongly disagree; (-1) = disagree; 0 = undecided; 1 = agree; 2 = strongly agree). The majority of interviewees either ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ with the majority of the items, and this limited variation makes the identification of response patterns unreliable. Also, because questions were not randomised, the interpretation of any covariance may be hindered by sequential artefacts and the altered item formulations. Conclusive comparisons between questions, groups and conditions, however, can be excluded on various methodological reasons. Furthermore, a quantitative validation of the dimensions in the form of a confirmatory factor analysis, for example, is not possible with the available data. In keeping with the exploratory character of the study, we shall therefore now give a cursory presentation of the descriptive figures:

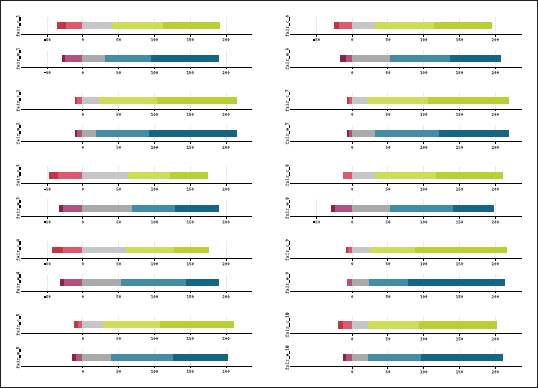

Table 1A in the appendix presents a breakdown of the results for the dimensions of planning security, performance assessment, task briefing, and remuneration level. Figure 1 compares workers’ expectations concerning crowdwork (fair_c_*; lighter colours/grey) and their expectations concerning regular employment (fair_w_*; darker colours/grey). Our qualitative results had already shown that workers experience the lack of planning security in the crowdwork sector as a specific source of injustice. This is why most interviewees consider crowdwork as a form of secondary employment only. Nevertheless, interviewees’ expectations of a steady flow of jobs and tenders (‘fair_*_1’) is only slightly lower for crowdwork than for conventional employment ( Figure 1 , first bars on top).

Figure 1. Dimensions of justice. Crowdwork (fair_c_*; lighter colours/grey) versus work in regular employment (fair_w_*; darker colours/grey).

Source: Authors

As a result of the structural anonymity and lack of transparency of crowdworking platforms, the absence of opportunities to influence or object to performance assessment and their criteria is a fundamental problem. This problem was raised in the qualitative interviews. The quantitative data on the items ‘fair_*_2’ to ‘fair_*_6’ underscore the relevance of this issue, although the possibility of influencing performance evaluations seems to be considered less important than other aspects of performance-related justice ( Figure 1 , following bars).

Like the qualitative data, the quantitative data shows that unclear or contradictory task briefings very often constitute a further source of perceived injustice. The items ‘fair_*_7’ and ‘fair_*_8’ are considered important, and potentially even more important than in regular employment (Figure 1). The quantitative results also confirm the qualitative results concerning the importance of remuneration for the items ‘fair_*_9’ and ‘fair_*_10’. Nevertheless, the interviewees consider fair pay just as important in crowdwork (_c_) as work in traditional employment (_w_) ( Figure 1 , last bars):

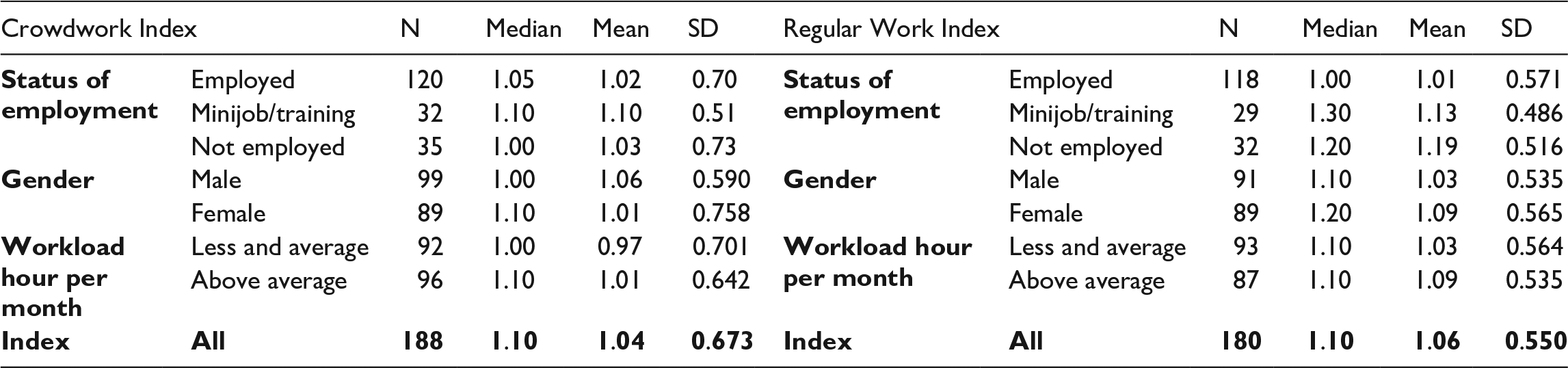

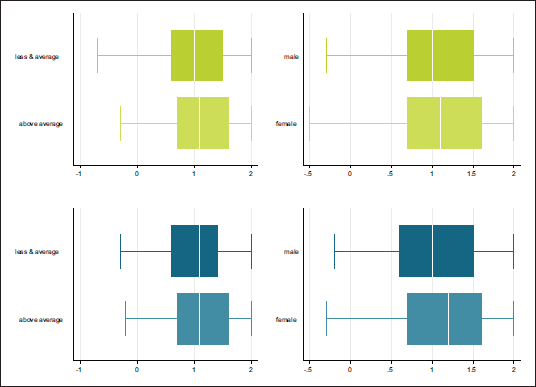

An index that summarises all 10 dimensions of perceived justice (Table 1) also reveals a strong similarity between expectations towards crowdwork (N = 188, mean = 1.04, SD = 0.673) and gainful employment (N = 180, mean = 1.06, SD = 0.550). Hardly any variation is observable when comparing index values by current employment status. Medians and means differ only slightly, the differences are more evident in the distribution. The highest expectations are found among respondents who are currently not in employment with regard to normal employment ( Figure 2 , blue boxplots). All differences are generally small, however, and it seems that one’s own work experience hardly makes a difference in the reported expectations. Moreover, gender or one’s monthly workload in crowdwork – operationalised as average or less than average versus above average using group median as the cut-off – make little difference (Table 1 and Figure 3):

Table 1. Index values for crowdwork by employment status, gender and crowdwork workload.

SD: standard deviation.

Source: Authors

Figure 2. Justice expectations. Boxplots for crowdwork (above) and regular employment (below) differentiated by employment status (see also Table 1).

Source: Authors

Figure 3. Indices of fairness expectations. Boxplots for crowdwork (above) and regular employment (below) by gender and crowdwork workload (see also Table 1).

Source: Authors

In sum, our quantitative survey provides further evidence affirming the results of the qualitative interviews. Crowdworkers’ justice expectations differ little between crowdwork and conventional employment. Note, however, that the survey explorative only, with no claim to be representative of crowdworkers on the platforms investigated or for crowdworkers in general. Because we do not know the socio-demographics of either population, analysis of how the study sample may differ is not possible.

Conclusion and implications

Our results confirm existing research on the expectations of workers concerning performance-related justice and show that crowdworkers’ justice expectations are similar to those held by employees in conventional work arrangements. We nonetheless do not know (and our data does not allow us to draw any conclusions on this) whether this commonality is due to a form of transference (since the majority of the interviewees earn their living via traditional forms of employment and potentially carry over their expectations from this sector to the online world), and/or whether this similarity is a transition phenomenon that might intensify in the future, should traditional employees increasingly be displaced by the self-employed.

We nonetheless observe that crowdworkers do articulate principles of performance-related justice and that they set these principles in relation to their negative experiences with platform-mediated jobs. Thus, although crowdworkers in German-speaking countries voluntarily take low-paid work and agree to an employment relationship in which their rights as workers are poorly protected in comparison to conventional employees, they nevertheless hold crowdwork and conventional forms of employment to similar standards of justice.

Our study has implications for future labour-market policy. To date, there has been little research about how crowd workers perceive their work arrangements, but our study shows tentatively that crowd workers indeed perceive injustices in their work arrangements and that their discontent is focused onto four specific problem areas: planning insecurity, lack of transparency in performance evaluation, lack of clarity in task briefings and low remuneration. Future labour-market policies intended to support crowdworkers would likely make a positive impact for them if targeted to these specific areas.

Reference Stewart and StanfordStewart and Stanford (2017) lay out broad institutional options for regulating platform-mediated work. The authors note the possibility of specifying or expanding the definition of ‘employment’ and ‘employer’ to create a new regulatory category of ‘independent work’ to which existing regulatory standards can be applied. This would make it possible to grant worker rights (as currently accepted) not only to employees in conventional arrangements but also to self-employed persons in the gig economy. Our finding that crowdworkers’ claims to justice in crowdwork are similar to their claims regarding conventional employment suggests that applying existing regulatory standards to crowdwork, as outlined by Stewart and Stanford, makes sense from the perspective of crowdworkers at least.

Despite the strong cross-confirmation of our qualitative and quantitative results, these data have limits for making general inferences. This is partly because of the lack of comparable data due to the fact that available labour market statistics are strongly oriented towards traditional forms of employment. For further discussion of this difficulty and of various possible data collection methods, see also Reference Pongratz and BormannPongratz and Bormann (2017: 179–181). Also, like all studies on crowdwork, our investigation is faced with the difficulty that crowdworking platforms do not make their data publicly available, which hinders assessment of the total number and demographics of currently active crowdworkers.

A word about our normative position regarding justice and employment. In a comment on Reference DubetDubet’s (2008) study of perceptions of injustice in the workplace, Reference Kronauer, Misselhorn and BehrendtKronauer (2017) remarks that exclusion and injustice are necessary characteristics of conventional employment, thus implying the idea that employees might experience more or less justice is a fiction. For Reference Kronauer, Misselhorn and BehrendtKronauer (2017), the true injustice is that while one’s inclusion in the model of gainful employment is supposedly bound up with one’s own performance and thus judged by standards of performance-related justice, workers are in fact tied to overarching market mechanisms that they are powerless to influence (p. 237). While we do not deny this, our approach is to take at face value what workers think about justice and injustice within their work arrangements. If workers can articulate standards of justice and apply them to their work arrangements, then we believe they have validity as objects of empirical study and meaning for social policy, independently of their power to change the world.

Funding

The authors received some financial support for the empirical research, authorship and publication of this article in the context of the research project ‘diGAP – Decent Agile Project Work in the digitised World’ (ref. no. 02L15A306), jointly funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) and the European Social Fund (ESF). Some of the conceptual work for this publication was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – project number 442171541.

Appendix 1

Dimensions of perceived performance-related justice

Table 1A. Overview of items used in assessing perceived performance-related justice.

Source: Authors