The National Health Service Litigation Authority (NHSLA), established in 1995 to handle compensation claims against the NHS, reports that £769 million was paid in connection with clinical negligence claims during 2008/2009, up from £633 million in 2007/2008. 1 Against a total annual budget for the NHS of approximately £75 billion (excluding the capital budget), litigation costs represent approximately 1%. In these straitened times when the NHS is expected to make savings of over £20 billion during the next 4 years, a clinical governance input to service delivery is an important area of focus. On a personal level, the causes of litigation represent a physical or mental damage to a patient or their carer, a majority of which could have been avoided. For the psychiatrist or their health professional colleagues they represent a failure in a patient's journey through the mental health system and often a traumatic episode in the professional's career. As many of the more lurid claims are reported in the press, they have the power to undermine the standing of mental health services, particularly where sex, violence and death are involved.

In an attempt to begin to understand the complexity underlying the headline figure of £769 million, a request was made to the NHSLA for the data relating to psychiatry to identify some of the key pitfalls to avoid. In this paper we reveal how we have used the data provided to construct a simple and possibly generalisable model of a patient journey through a hospital event to understand the distribution of causes of litigation. Similarly, the effects of the error have been extracted and categorised to provide a meaningful classification of the impact on the patient.

Method

Following a request to the NHSLA under the Freedom of Information Act 2003, a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet containing litigation data directed at NHS psychiatric services between 1995 and 2009 was received. The data included: event date, a vignette of the incident, NHSLA-allocated cause(s), injuries sustained, status (open or closed), and amount of damages paid and to whom (claimant, claimant's legal team and NHS legal team). Causes of litigation/injury had been grouped by the NHSLA into 43 domains which we rationalised to 39 by re-assigning 4 domains that related to outcomes (self-harm, sexual abuse, unexpected death and not specified) based on their vignette detail. The rationalised list and status are shown in Table 1.

To correlate the causes of claims to their position in a generalised patient journey of a mental health event, we adapted a model developed by the Tees and North East Yorkshire Health Authority. 2 The allocation was performed using best fit, based on the detail contained in the vignette. Table 2 relates each of the NHSLA-allocated causes for litigation to the stages of the generalised patient journey. For example, stage 10 ‘patient assessed (risk)’ consists of the following NHSLA domains: failure to supervise, injury by another patient and injury to others by the patient.

Results

Since 1995, there have been a total of 1213 litigation claims against the NHS where the specialty recorded was psychiatry, at a total cost of £47.2 million. Of the total claims, 980 have been closed (81%), with 662 attracting compensation (68%). The mean compensation payment was £71 299. It is worth noting that five individual claims exceeded £1 million, accounting for a total of £10.7 million (25%).

TABLE 1 National Health Service Litigation Authority (NHSLA)-allocated litigation cause and its frequency of occurrence (1995–2009)

| NHSLA-allocated litigation cause | Closed, n | Open, n |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Application of excess force | 13 | 2 |

| 2. Assaulted by hospital staff | 46 | 17 |

| 3. Bacterial infection | 0 | 1 |

| 4. Clinical trial | 1 | 0 |

| 5. Diathermy/burns | 0 | 1 |

| 6. Error in agent/dose/route | 4 | 3 |

| 7. Failure/delay in treatment | 68 | 31 |

| 8. Failure to act on abnormal results | 2 | 0 |

| 9. Failure to carry out post-operative observations | 7 | 2 |

| 10. Failure to follow-up arrangements | 19 | 2 |

| 11. Failure to recognise complications | 31 | 7 |

| 12. Failure to supervise | 178 | 40 |

| 13. Failure to warn – informed consent | 12 | 6 |

| 14. Failure/delay admit to hospital | 25 | 8 |

| 15. Failure/delay refer to hospital | 9 | 0 |

| 16. Failure to interpret X-ray | 0 | 1 |

| 17. Failure to perform tests | 3 | 0 |

| 18. Failure to X-ray | 1 | 1 |

| 19. Failure/delay diagnosis | 85 | 20 |

| 20. Inadequate nursing care | 36 | 17 |

| 21. Inappropriate case selection | 1 | 0 |

| 22. Inappropriate discharge | 41 | 14 |

| 23. Inappropriate treatment | 53 | 10 |

| 24. Incident committed by patient who absconded/was discharged | 59 | 13 |

| 25. Incorrect injection site | 1 | 0 |

| 26. Injured by another patient | 54 | 7 |

| 27. Injury to others by patient | 25 | 5 |

| 28. Intra-operative problems | 3 | 1 |

| 29. Lack of assistance/care | 68 | 15 |

| 30. Lack of facilities/equipment | 6 | 0 |

| 31. Lack of pre-operative evaluation | 1 | 0 |

| 32. Medication errors | 54 | 3 |

| 33. Operation on wrong person | 1 | 0 |

| 34. Performance of operation not indicated | 1 | 0 |

| 35. Problem blood fluids | 1 | 0 |

| 36. Problems with medical records (breach of confidence) | 15 | 0 |

| 37. Unlawful detention | 21 | 2 |

| 38. Wrong diagnosis | 31 | 4 |

| 39. Death by natural causes | 4 | 0 |

| Total | 980 | 233 |

The remaining 233 open claims (19%) are relatively recent additions to the database and might be expected to inflate the number of compensated claims as they reach a conclusion.

Litigation causes

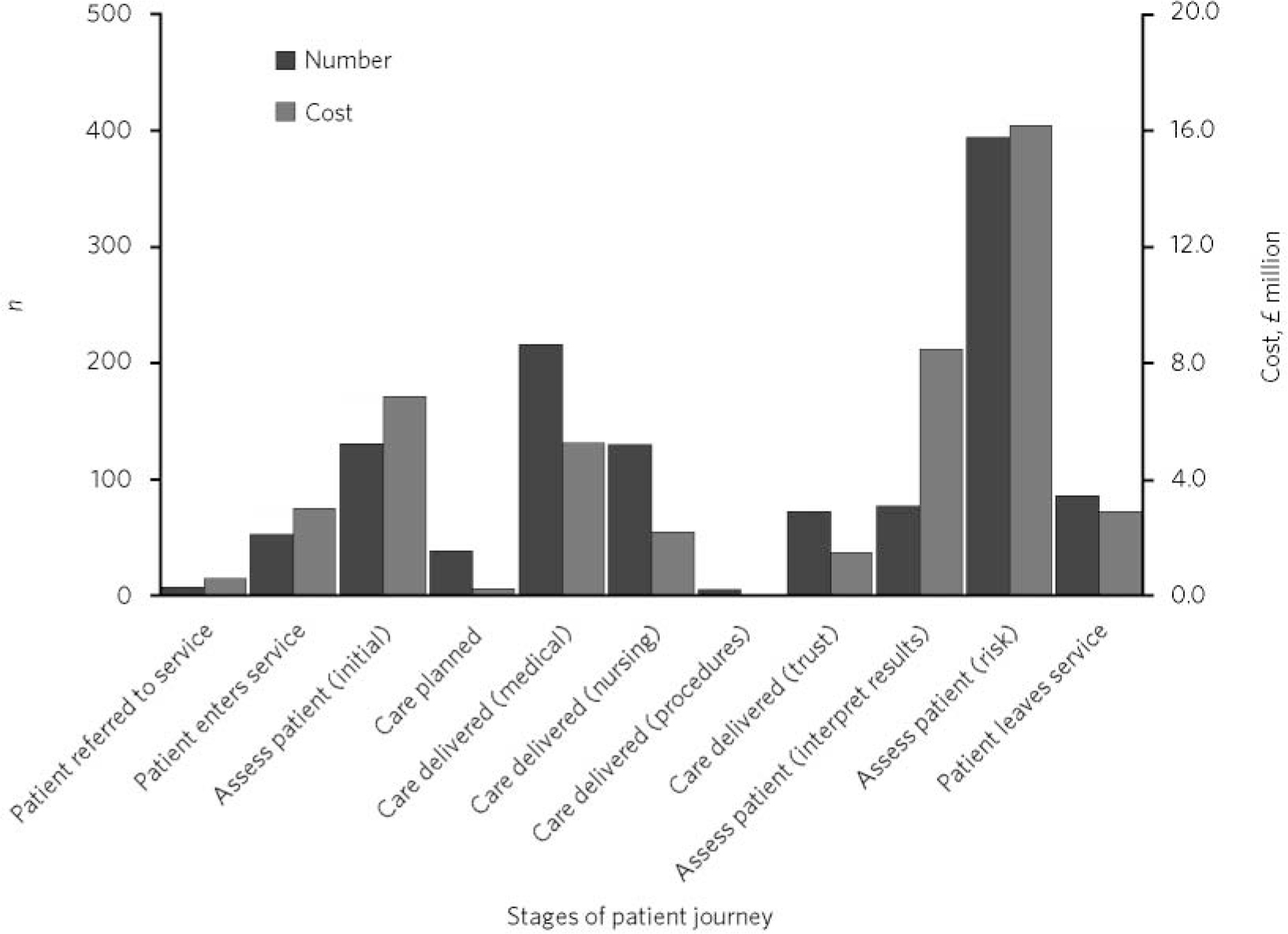

Allocation of the 39 causes of litigation to their most likely occurrence in the stages of a generalised patient journey (Fig. 1) reveals that 67% (£31.6 million) of the total compensation claims are derived from failures in patient assessments: patient assessed (initial) £6.9 million, patient assessed (interpret results) £8.5 million and patient assessed (risk) £16.2 million (Fig. 1). The same categories were associated with 50% (n = 604) of the total number of claims (patient assessed (initial) 132, patient assessed (interpret results) 78 and patient assessed (risk) 394). Table 3 provides some verbatim examples of the vignettes associated with each of these categories (full version of the table is available in an online supplement to this paper). Patient assessment is the key weak point.

Patient outcomes

Analysis of the vignettes associated with compensated claims revealed 62 separate types of injury. By mapping each of the injuries and their associated costs to a crude damage outcome, a distribution can be determined as shown in Fig. 2.

Comparative litigation costs and claims

The care planned and three care delivered stages produced mean costs significantly smaller than the overall mean cost (£71 299): care planned £10 736, care delivered medical £25 209, nursing £28 392 and trust £40 602. In contrast, the mean cost of ‘assess patient (interpret results)’ appears disproportionately large at £108 567. However, this category contains three of the five single largest payments, each exceeding £2 million, removal of which reduces the mean cost to a still high £44 935. The mean cost of both assess patient (risk) £72 956 and assess patient (initial) £104 360 exceed the overall mean cost.

In terms of the proportion of successful/total claims there is little difference between the two groups, with the exception of care delivered medical (54/216, 25%), which is significantly smaller than the remainder: care planned 21/38 (55%), care delivered – nursing 77/130 (59%) and trust 37/73 (51%), assess patient – initial 66/132 (50%), interpret results 46/78 (59%), risk 222/394 (56%).

Allocation of damages

Damages paid to the patient or their carers represent the majority of the total cost at £29.2 million (62%), with the claimants’ legal costs adding a further £10.9 million (23%) and the NHSLA's own defence costs amounting to £7.1 million (15%; Fig. 3). Interestingly, in 413 claims which settled (62%), the cost of litigation (claimant's and NHS legal team's costs) exceeded the value of damages paid to the patient. Claimant's legal costs constituted the total settlement in 213 of all claims (18%). In 15 cases (1.2%) no legal fees were paid and in 2 (0.2%) NHS legal fees were the only payment.

TABLE 2 National Health Service Litigation Authority (NHSLA)-allocated litigation causes grouped by generalised patient journey

| Stage in patient journey | Litigation causes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient referred to service | 15. Failure/delay in referral to hospital | |||||

| Patient assessed – initial | 17. Failure to perform tests | 18. Failure to X-ray | 19. Failure/delay diagnosis | 31. Lack of pre-op evaluation | 43. Wrong diagnosis | |

| Patient enters service | 14. Failure/delay to/admit to service | 42. Unlawful detention | ||||

| Care planned | 4. Clinical trial | 13. Failure to warn | 30. Lack of facilities/equipment | 38. Problems with medical records | ||

| Care delivered – nursing | 1. Application of excess force | 2. Assault by hospital staff | 20. Inadequate nursing care | |||

| Care delivered – medical | 6. Error – agent/dose/route | 7. Failure/delay treatment | 23. Inappropriate treatment | 32. Medication error | 34. Operation on wrong person/body part | 36. Need for operation not indicated |

| Care delivered – procedures | 3. Bacterial infection | 5. Diathermy burns | 21. Inappropriate case selection | 28. Intraoperative problem | ||

| Care delivered – trust | 29. Lack of assistance/care | |||||

| Patient assessed – interpret results | 8. Failure to act on abnormal test results | 9. Failure to carry out post-op observations | 10. Failure to follow-up arrangements | 11. Failure to recognise complications | 16. Failure to interpret X-rays | 37. Problem blood fluids |

| Patient assessed – risk | 12. Failure to supervise | 26. Injury by another patient | 27. Injury to others by patient | |||

| Patient discharged | 22. Inappropriate discharge | 24. Incident in community by absconded/discharged patient |

TABLE 3 Example vignettes and litigation costs for ‘assess patient’ categories

| Stage in patient journey | Vignette | Litigation cost |

|---|---|---|

| Patient assessed (initial) | Patient with schizophrenia. Failure to assess severity of mental condition and admit to hospital, leading to attempted suicide with paralysis to right side of body |

£168 394 |

| Patient assessed (interpret results) |

Renal failure in claimant due to lithium treatment. Alleged failure/ delay to monitor levels of creatinine which could have prevented this |

£131 096 |

| Patient assessed (risk) | Alleged refusal of antidepressants leading to patient walking in front of a train resulting in amputation of both legs |

£515 753 |

Discussion

In the financial year 2008/2009, litigation cost the NHS £769 million, 1 more than 1% of its total £74.2 billion primary care trust budget. 3 Of the total clinical negligence claims settled by the NHSLA since 2003/2004 (at an overall cost of £3 466 million), 1 those attributed to psychiatry (£16.1 million) represent less than 0.5%. By contrast, birth-related claims account for 20% of overall claims but 60% of the financial payouts. Reference Baker, Thomson, Sandars, Sandars and Cook4 Psychiatry therefore appears to be a relatively low-risk specialty from a medico-legal perspective.

In psychiatric services, two-thirds of completed claims attract a compensation settlement. In the care planning and care delivered stages of the patient's journey the settlements are relatively small in comparison with the overall mean. In the three patient assessed stages, the compensation payments are at, or significantly above, the average, notwithstanding that the largest settlement dominates patient assessed (initial) and three of the remaining four largest single payments distort the patient assessed (interpret results). Together, the patient assessed stages account for 67% of the total compensation.

FIG 1 Comparison of total number of claims (open and closed) and compensation settlements to date (closed) distributed across the stages of a generalised patient journey.

FIG 2 Classification of damages by litigation cost.

FIG 3 Allocation of litigation costs.

In general, the vignettes associated with patient assessed (risk) centre on failure to anticipate attempted suicide, self-harm or infliction of harm on others, either by patients leaving in-patient units unsupervised or by inappropriate observation regimes being implemented or executed. Errors involving patient assessed (interpret results) include vignettes describing failure to anticipate, monitor or act on evidence of drug toxicity and side-effects, and failure to institute follow-up arrangements once concerns are identified. Failure to identify a mental illness or diagnosing a mental illness when the cause was medical contributed to the patient assessed (initial) category. The vignettes, however, provide scant detail and in some cases appear to have been miscoded, as demonstrated in Table 3 (and further in the online supplement). But even where one of the larger settlements (£2 188 152) would seem to fit into the patient assessed (risk) rather than patient assessed (interpret results), the general category of patient assessment is not affected.

Psychiatrists should not see the ramifications of these data as their sole responsibility. Many of the vignettes refer to the multidisciplinary nature of modern medicine, with separate specialties, general practitioners, nurses and trusts all being implicated. However, psychiatrists should be seen to be leading improvements in the quality of care and safety of patients in the mental healthcare system. To assist in this process, we have attempted to step back and review the evidence of failures over a 15-year period and provide a first-pass analysis of the key clinical, patient and economic outcomes. By allocating causes of litigation to a generalisable patient journey we have highlighted the stages which attract the greatest number of claims and financial settlements. As the psychologist James Reason reported when discussing the modus operandi of ‘high-reliability organisation’, ‘Instead of isolating failures, they generalise them, instead of making local repairs they look for systems reforms’ (p. 770). Reference Reason5 Similarly to high-reliability nuclear power plant operations or air traffic control systems which cannot be allowed to fail, healthcare needs to develop a similar ethos.

Over a decade ago, the past chief medical officer, Sir Liam Donaldson claimed that ‘The [National] Health Service has yet to develop a simple way to allow the important, generalisable lessons to be extracted from the extensive analysis, information gathering and independent judgement which now underpins the handling of complaints’ (p. 64). Reference Scally and Donaldson6 Although a plethora of organisations, such as the National Patient Safety Agency, the National Audit Office and the Healthcare Commission were established (and may now be amalgamated, disbanded or re-branded, e.g. Healthcare Commission became Care Quality Commission), it appears that there is still a long way to go. The concept of allocating errors (compensable or otherwise) to a generalisable patient journey at a local and national level may go some way to beginning to satisfy the past chief medical officer's challenge.

What is surprising is that for many domains of medical care, no uniform protocol for risk analysis has been adopted in the NHS. For example, the risk of suicide in the 4 weeks after receiving psychiatric in-patient care is around 100 times greater than that for the general population, Reference Geddes and Juszczak7 but only recently was it recommended that interventions should be developed to reduce risk in this period. Reference Gunnell, Hawton, Ho, Evans, O'Connor and Potokar8 When protocols of care do exist, they often appear to be locally generated, suggesting that there may be relatively little transfer of learning across the healthcare community.

The data presented here suggest that what is needed is a systematic high-level approach to risk analysis that should be compiled by both the expert clinician and professionals with expertise in risk assessment. This is an approach the self-regulated professions (including, until recently, the legal profession) have been slow to adopt. Not only will this help reduce the waste of financial resources required to settle claims, but more importantly minimise the distress, disability and death suffered by patients and their carers.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.