Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is a well-recognised psychotherapeutic intervention for the treatment of a number of psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder. 1 Furthermore, CBT techniques have proven to be efficacious in targeting specific conditions such as chronic delusions and hallucinations in schizophrenia. Lord Layard examined the need for psychological treatments in the UK and speculated that there will be a demand to train 5000 more psychological therapists by 2013, mostly in CBT. Reference Layard2

However, clinicians practising CBT note a consistent number of cancelled or not attended appointments. More importantly, a number of patients start the therapeutic process but terminate the therapy earlier than agreed, without comprehensively explaining the reasons or demonstrating a consolidation of the results. This is despite the fact that some patients appear initially to be well engaged or even show a marked improvement with a relatively low number of sessions.

Attrition rates in psychotherapy are high, ranging from 20 to 60% depending on the setting where the intervention is delivered and the modality of the intervention. Reference Baekeland and Lundwall3-Reference Davis, Hooke and Page11 The difficulty in establishing a precise figure lies in the fact that there is no uniformity in the definition of treatment discontinuation. Reference Baekeland and Lundwall3 Some researchers define early treatment discontinuation as terminating the treatment without previous agreement with the therapist, others use the number of visits or the length of time as criteria. The definition affects the results, but consensus has not been established. Reference Principe, Marci, Glick and Ablon12

Treatment discontinuation represents a significant problem in mental health, as it seems that generally the outcomes of those who dropped out of treatment are poorer than for people who stay in treatment or are equivalent to outcomes of those who were untreated, Reference Arnow, Blasey, Manber, Constantino, Markowitz and Klein13-Reference Pekarik5 and 21-46% of those patients end up getting treated in another setting within the next year. Reference Baekeland and Lundwall3,Reference Persons, Burns and Perloff4 Furthermore, treatment discontinuation constitutes a financial loss for services in taxpayer-funded systems such as the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK and for the individual patients themselves. Reference Oei and Kazmierczak8 This may reduce the therapist's job satisfaction, which in turn may lead to increased staff turnover. Reference Bados, Balaguer and Saldana14 The same author argues on an emotional cost to the therapists. Reference Bados, Balaguer and Saldana14 With regard to the economic aspect, some researchers Reference Pekarik16-Reference Oei and Kazmierczak8 argue that treatment discontinuation represents a waste of resources in a system where the demand for psychotherapy exceeds the limited supply. Davis et al Reference Brogan, Prochaska and Prochaska9 point out that the overall efficacy of CBT interventions is lessened when treatment discontinuation is considered.

We are of the opinion that addressing the problem of early treatment discontinuation is paramount in view of optimising any publicly funded healthcare system, the allocation of resources and the waiting lists. In this paper we review the literature specifically on attrition in high-intensity CBT interventions.

Method

An electronic literature search was done by using Medline, PsycINFO, Embase and the Cochrane Library. Key terms used were ‘CBT’, ‘cognitive behaviour therapy/cognitive therapy’, ‘patient dropouts’, ‘early termination’, ‘patient compliance’ and ‘psychotherapy’. The terms ‘CBT’, ‘psychotherapy’ and ‘cognitive therapy/cognitive behaviour therapy’ were initially combined to get the results; the same was done for ‘early termination’, ‘patient dropouts’ and ‘patient compliance’. After this, the results of both the combinations were combined to get the final numbers. Duplicates were excluded. We did not set any restriction regarding the language or the year of publication. We did not search for unpublished articles. We screened all the abstracts to select the relevant articles, including all the papers that explicitly mentioned ‘dropout’ and CBT interventions either in the title or in the abstract. We have excluded articles that specifically described non-CBT psychotherapies, outcomes other than early treatment termination and all the articles that mentioned the general term ‘psychotherapy’. All types of studies were considered, including those of lower quality or opinion papers. Every article selected was reviewed by both A.S. and R.S., including references for additional cited articles. Finally, the search was completed by cross-referencing the selected papers.

Results

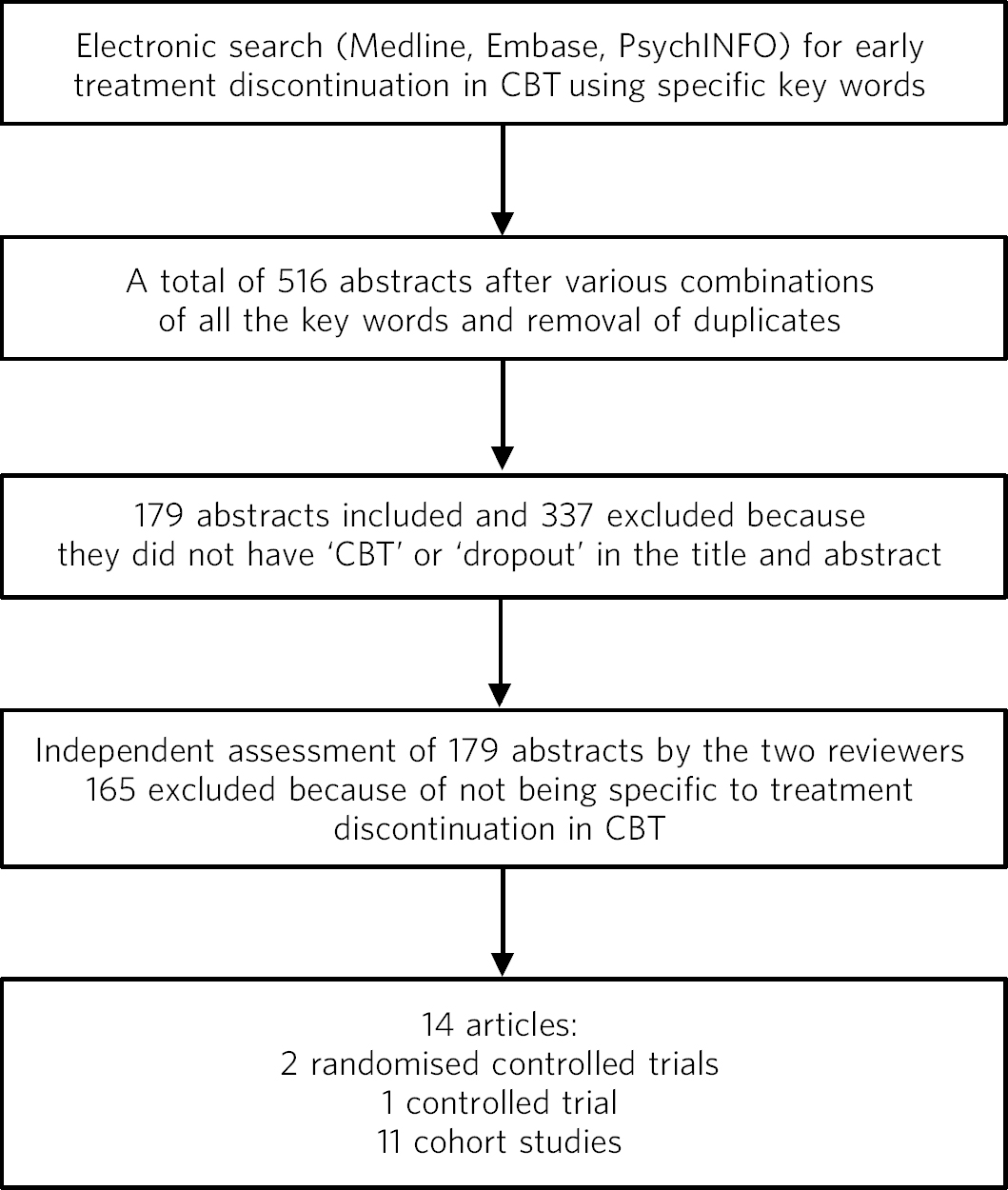

In Medline, Embase and PsycINFO, the keyword ‘early termination’ generated 1625 results, ‘CBT’ 9574, ‘psychotherapy’ 69 115 and ‘cognitive therapy/cognitive behaviour therapy’ 21 468 results. Combining the terms ‘CBT’, ‘psychotherapy’ and ‘cognitive therapy/or cognitive behaviour therapy’ generated 94 666 results. The term ‘patient dropouts’ generated 4597 results and ‘patient compliance’ 21 796 results; the combination of these two terms generated 27 827 results. The combination of all the search terms generated a total of 582 abstracts. After removing the duplicates, we obtained 516 abstracts. Finally, 179 abstracts were selected for the initial screening, based on the inference from the title as to whether the abstract would be dealing with CBT or ‘dropouts’. The final screening and review of these 179 abstracts generated 14 articles that fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in this review. Two of these articles were randomised controlled trials, one was a controlled trial and the rest were cohort studies, both prospective and retrospective (Fig. 1).

Fig 1 Study process. CBT, cognitive-behavioural therapy.

There is some controversy in the results regarding the relationship between demographic variables and patients who drop out of treatment. In general, it seems that younger service users with low education level and of lower social class background are more likely to drop out of CBT. Reference Persons, Burns and Perloff4,Reference Brogan, Prochaska and Prochaska9,Reference Davis, Hooke and Page11 In a randomised controlled trial by Arnow et al, Reference Davis, Hooke and Page11 those of ethnic minority background are reported to have significantly higher drop-out rates. However, in a cohort study of group CBT for depression, Reference Wierzbicki and Pekarik7 age and education level did not statistically differ between those who dropped out, whether early or late, and those who completed the therapy. Similar results are reported in other studies where general demographic variables did not differ between the two groups. Reference Pekarik19-Reference Borghi23

The diagnosis is another contentious issue. There is no robust evidence supporting an association between any particular diagnosis and early treatment discontinuation rates, Reference Principe, Marci, Glick and Ablon12 a finding confirmed by all the studies in that review. However, Persons et al Reference Persons, Burns and Perloff4 report that patients with personality disorders were more likely to drop out of treatment. In a study of early discontinuation of CBT for bulimia, Reference Borghi23 higher level of borderline and dissociative symptomatology was associated with discontinuation. These findings are not supported by Arnow et al's study, Reference Davis, Hooke and Page11 in which comorbid personality disorders were equally prevalent in those who completed the treatment and those who dropped out, and only anxiety disorder correlated to the latter. The severity of the depressive symptomatology seems to be correlated with early discontinuation rates. Reference Persons, Burns and Perloff4,Reference Frank, Gliedman, Stanley, Nash and Stone22,Reference Steel, Jones, Adcock, Clancy, Bridgford-West and Austin25

Common sense suggests that practicalities may play a role in a number of patients who do not return to therapy. These include difficulties with transport, finances, busy timetables or time constraints, clash with other commitments, personal problems and taking time off work. Only two studies Reference Principe, Marci, Glick and Ablon12,Reference Pekarik19 reported significant results for those variables, one citing high scores for time and transportation. Reference Pekarik19 Surprisingly, only one study reported dissatisfaction with treatment or therapist as a reason for terminating therapy. Reference Principe, Marci, Glick and Ablon12

There are references to other causes of early treatment discontinuation in the literature, although sometimes they are only mentioned or partially explored. Davis et al Reference Brogan, Prochaska and Prochaska9 examined data from an archive of group CBT and identified low self-esteem at admission and poor relationship status as the only two predictors of treatment discontinuation. However, in a controlled trial by the same authors, completing a self-esteem module before commencing group CBT did not decrease the drop-out rate. Reference Brogan, Prochaska and Prochaska9 In a cohort study by Steel et al Reference Masi, Miller and Olson20 on predictors of early treatment termination in CBT for bulimia nervosa, the patients who were more likely to drop out had a higher weight fluctuation, scored higher in the subscale of Ineffectiveness of the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (feelings of general inadequacy, insecurity, worthlessness, emptiness, low self-esteem and negative self-evaluation), and had a higher level of pre-treatment depression, hopelessness and external locus of control. Similar results are reported in a study by Coker et al. Reference Frank, Gliedman, Stanley, Nash and Stone22 In a study by Westra et al, Reference Simons, Levine, Lustman and Murphy24 low self-esteem and pre-treatment hopelessness were also predictors of drop-out in cognitive-behavioural group therapy for depression. Short total sleep time was reported to be associated with treatment discontinuation in a paper on CBT for insomnia. Reference Steel, Jones, Adcock, Clancy, Bridgford-West and Austin25 In another study of CBT in eating disorders in an in-patient setting investigating personality dimensions of those who discontinued their treatment v. those who completed it, Dalla Grave et al Reference Hillis, Alexander and Eagles21 found only one significant difference in the subscale of Persistence in the Temperament and Character Inventory.

Finally, in a randomised trial, Arnow et al Reference Davis, Hooke and Page11 found a statistically significant difference in early working alliance total scores between those who completed their psychotherapy treatment and those who did not.

Discussion

From this review it emerged that there is little specific literature investigating a very common and expensive problem such as early treatment discontinuation in CBT interventions. Furthermore, some of the literature is about treatments for specialist conditions such as eating disorders and insomnia. We could not find any paper addressing treatment discontinuation in CBT for anxiety disorders and found only a few for depression. This review seems to indicate that there is no single robust predictor of treatment discontinuation in CBT. Another finding is that the prevalence of treatment discontinuation in CBT interventions ranges from 19 to 50% across studies.

The strength of this review is that the selection criteria were very strict, with the exclusion of every paper mentioning the general term psychotherapy. This was because psychotherapy includes a variety of interventions other than CBT. Findings about treatment discontinuation and general psychotherapy do not necessarily apply to CBT interventions. However, paradoxically this is also a limitation of the study, as this has undoubtedly excluded seemingly important findings about treatment discontinuation. Moreover, we reviewed only those articles in which the terms ‘CBT’ and ‘dropouts’ appeared either in the title or in the abstract. We recognise that this may have led to excluding a large number of papers mentioning ‘dropouts’ in different contexts in the main body.

Hunt & Andrews Reference Dalle Grave, Calugi, Brambilla and Marchesini26 suggested that high discontinuation rates are an indicator of poor performance in psychotherapy. This is arguably a very good point and perhaps services should invest more into decreasing those rates, for example through sponsoring research projects to establish which factors can be addressed and modified in the short and long term. The NHS information service in the UK calculated an average cost of a CBT session as £58. Reference Coker, Vize, Wade and Cooper27 Even a small reduction in non-attendance rates will produce substantial savings. Furthermore, the optimisation of resources may have an effect on staff morale and the public image of health services.

There does not appear to be any consensus on specific factors responsible for treatment discontinuation in CBT interventions. More systematic research is needed to address this very common issue as this has a huge potential in terms of quality of services delivered and their economic value.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.