Seclusion is an intervention commonly used in psychiatry to manage acute behavioural disturbance, particularly physical aggression to others.Reference Sullivan, Wallis and Lloyd1 The use of seclusion in psychiatric hospitals in New Zealand and Australia is frequent. The practice involves isolating individuals in a locked room from which they ‘cannot freely exit’.Reference Meehan, Vermeer and Windsor2 According to New Zealand Health and Disability Services, seclusion should only be used as a last resort, and only if the person is presenting a risk to themselves or others.3

There is continuing debate about the value of seclusion in mental health services and this study was initiated to determine the exact frequency of this procedure and factors associated with its use in a remote area of New Zealand. The use of seclusion was examined over a 12-month period in a 20-bed general adult acute psychiatric unit in the mental health unit at Southland Hospital in Invercargill. The unit serves a population of 107 000 people of whom 15% are of Maori origin. It has two purpose-built seclusion rooms adjacent to the two main wards in the hospital. These rooms are locked off physically from the two acute adult wards but the care is fully integrated as the same key staff are responsible for the patients in both settings.

In addition to determining the frequency of seclusion over the year of the study, the demographic characteristics of those in seclusion, the reasons for seclusion and the factors that determined the length of time spent in isolation were examined. A seclusion episode was recorded whenever a patient was transferred to the specialised locked facility. If a patient was secluded more than once, each episode was treated as a separate event.

Method

Information on all patients requiring seclusion during the 1-year study period, from 1 August 2007 to 31 July 2008, was collected. The reasons for seclusion were recorded by examining the events preceding the episode. The duration of seclusion and when this was initiated were also determined. The diagnosis of each patient, the Mental Health Act section applied at the time and the ethnicity and gender of the patients involved were recorded. Any pro re nata (p.r.n.) medication administered before the seclusion episode was initiated was noted. The drug treatment received during the seclusion episode was subsequently assessed independently by two of the psychiatrist authors (S.T. and D.G.), and the adequacy of this treatment was determined according to the recommendations given in the Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines.Reference Taylor, Paton and Kerwin4 If the drug treatment given at the times of reviews in seclusion was in the doses recommended in the Maudsley guidelines, the adequacy of treatment was recorded as good. If the treatment given was not covered in these guidelines or if the dosage of the drugs given was more than 50% less than recommended, with due allowance for the age of the patient, the quality of treatment was determined inadequate. The chapters referred to in these guidelines were concerned mainly with the treatment of acutely disturbed patients with behavioural problems, but reference was also made to the treatment of acute mania, antipsychotic polypharmacy and drug treatment of depression. Where there was disagreement, which only occurred on one occasion, the most favourable assessment of the management received was recorded. Treatments other than medication were not assessed. Attempts to de-escalate and defuse behavioural disturbance were made in many cases but these interventions were not recorded.

This audit was carried out as part of a service quality assurance procedure. Monitoring of seclusion levels was seen as relevant to good-quality management of patients so no specific consent was sought from those involved as there was no direct patient contact during the investigation. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17 for Windows. The distribution of the length of time spent in seclusion was found to be positively skewed and both log transformation and inverse log transformation were carried out to attempt to convert the data to a normal distribution. The distributions revealed using both these techniques still did not fulfil the conditions for normality and so non-parametric statistics were performed. To minimise the influence of outliers, the period in seclusion was grouped into 9 separate categories, each lasting 12 hours, and analysis was performed on these data. Where the goodness of fit of the data was justified for categorical data, a χ2-test with Yates’ correction or Fisher's exact test was used.

Results

During the 12-month period of data collection there were 254 patients admitted to the mental health unit. Of these, 56 had multiple admissions during the study, 1 on six occasions, and in total there were 333 separate admission episodes. In total, 23 patients were secluded in 30 episodes during this period; some patients were secluded more than once. Thus, of all patients admitted to the unit, 9.1% were secluded. Table 1 shows the frequency of seclusion episodes and patient characteristics. The median age of those secluded was 34.5 years, with males non-significantly older than females (37.0 v. 31.0 years).

Significantly more males than females were secluded. None of the 5 females were secluded more than once, whereas 5 of the 18 males were secluded twice or more. Patients of Maori origin and those of continental European nationality were secluded more often than the indigenous New Zealand Pākehā (White) population. Those with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder were much more likely to be secluded than patients in other diagnostic categories. All five of the patients with bipolar affective disorder who were secluded were in the manic stage at the time. No relationship was found between diagnosis and event leading to seclusion or period of time in seclusion. There was a significant relationship between Mental Health Act status and diagnosis. All but one of the five patients on Sections 29 or 30 (both restrictive orders applied by a court, lasting for 6 months or longer, that required the patient to be reviewed regularly) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (the other patient had schizoaffective disorder), whereas the five patients with mania were all on Sections 11 or 13 (short-term orders lasting for 2 weeks or less applied by a consultant psychiatrist) (P<0.05; Fisher's exact test). The four Europeans were all detained under Sections 11 or 13.

Three-quarters of the seclusion episodes were initiated because of considerable marked agitation manifested by the patient, usually associated with threats of assault. There was a tendency for younger people to have physically assaulted someone before being secluded but this only occurred on five occasions. Half of all the seclusion episodes occurred during the evening shift, between 16:00 and 24:00, with exactly a third of episodes manifest at the time of the morning shift, between 08:00 and 16:00. In addition to seclusion, usually occurring just before the event, medication was given on seven occasions, either orally or intramuscularly in an attempt to defuse the behaviour exhibited. Receipt of this p.r.n. medication did not relate to gender, ethnicity, diagnosis or outcome.

The frequency of implementing seclusion was similar during the summer, autumn and winter but during the spring months seclusion was only carried out on three occasions (Table 2). With regard to days of the week when seclusion was used, six seclusion episodes were initiated on Mondays and Thursdays but only two episodes were recorded on Sundays and Tuesdays, with intermediate figures for the other days.

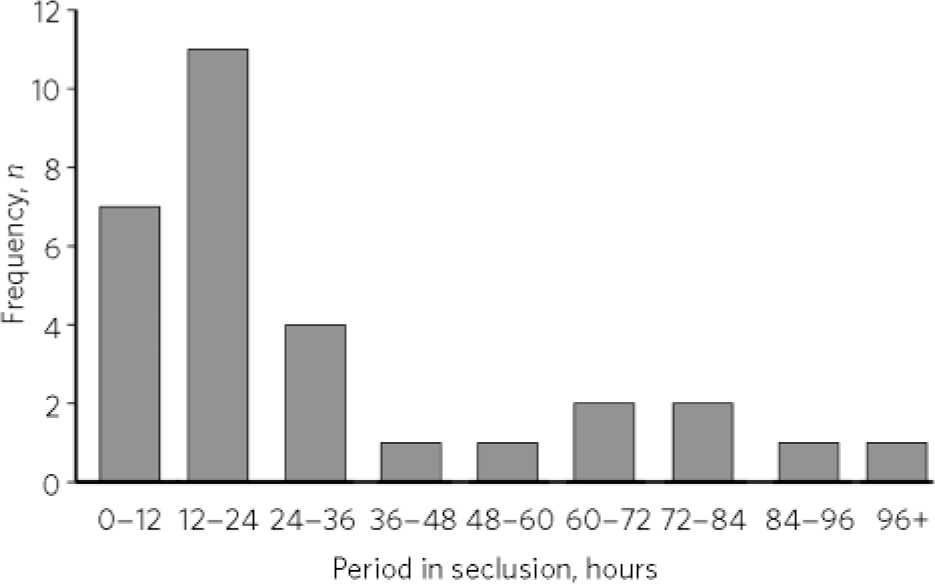

FIG. 1 Duration of seclusion episodes.

TABLE 1 Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the cohort of patients

| Characteristic | Total, n | Secluded, n (%) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 138 | 18 (13) | P<0.05 |

| Female | 116 | 5 (4) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| New Zealand Pakeha | 186 | 10 (5) | |

| Maori | 44 | 8 (18) | P<0.05Footnote a |

| European | 16 | 4 (25) | P<0.05Footnote a |

| Other | 8 | 1 (13) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Schizophrenia | 44 | 8 (18) | P<0.0001Footnote b |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 12 | 5 (42) | P<0.0001Footnote b |

| Bipolar disorder | 40 | 5 (13) | P<0.0001Footnote b |

| Major depression | 38 | 0 (0) | |

| Other psychoses | 6 | 0(0) | |

| Substance misuseFootnote c | 12 | 1 (8) | |

| Borderline personality disorder | 8 | 1 (13) | |

| Other | 94 | 3 (3) |

a. This level of significance refers to each of these ethnic groups in comparison with the New Zealand Pakeha group.

b. This comparison refers to the first three diagnostic categories combined with the remainder.

c. For patients with substance misuse who were dually diagnosed the accompanying psychiatric diagnosis was included as the prime diagnosis. Three of these patients had a diagnosis of mania.

TABLE 2 Seasonal frequency of seclusion events

| SeasonFootnote a | Episodes of seclusion, n | Total percentage | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summer (December-February) | 7 | 23 | ns |

| Autumn (March-May) | 9 | 30 | ns |

| Winter (June-August) | 11 | 37 | ns |

| Spring (September-November) | 3 | 10 | ns |

ns, not significant.

a. Seasons as experienced in New Zealand.

The median time spent in seclusion was 17 hours (s.d. = 28.0; mean 30.5; minimum 1.45, maximum 99). The median duration of seclusion initiated during the day shift seemed comparatively longer (24.2 hours) than seclusion initiated during the evening (16 hours) and night (9.15 hours) shifts, but this difference was not significant. Most (60%) of the patients in the secluded group were secluded only once. Thirteen per cent (4 patients) were secluded twice and one patient was secluded four times. Fig. 1 illustrates the duration of seclusion events.

To determine if there were any variables that contributed to the duration of the period in seclusion, a logistic regression was originally considered but was not performed because the distribution of the data was non-parametric. Therefore, each independent variable that could possibly affect the duration of seclusion was selected and the relationship between each variable and the dependent variable of seclusion duration was determined. The association between the putative determining factors and the outcome of seclusion was studied using χ2-tests and the Mann-Whitney U statistic. The independent variables selected for this analysis included suitability of medication in seclusion, age, gender, ethnicity, diagnosis, event preceding the seclusion episode, time of seclusion and whether p.r.n. medication was given before the seclusion episode.

The results of this analysis revealed only one significant factor contributing to the length of time spent in seclusion, namely the treatment prescribed while in the seclusion room (P = 0.045; Mann-Whitney U). The treatment given corresponded to that recommended in the Maudsley guidelines in exactly half of all seclusion episodes so in 50% the treatment prescribed was below standard. Analysis of the data revealed that the median period of time spent in seclusion was 16.45 hours (s.d. = 10.6; mean 18.5) for those who received treatment according to the Maudsley guidelines, whereas in those who received treatment unsupported by the recommendations in these guidelines the median duration of seclusion was 28.25 hours (s.d. = 34.3; mean 42.6).

Discussion

The seclusion rate in this sample is lower than that measured in the North Island of New Zealand earlier in the decade in the Waikato study. In this investigation carried out in 2000 there were 129 seclusion episodes reported in an acute adult psychiatry unit over a 9-month period.Reference El-Badri and Mellsop5 The area concerned was over three times larger than the catchment area covered by the Southland Mental Health Unit and the figures represented a seclusion rate of 5.5 per annum for every 10 000 people in the area covered. The equivalent figure for Southland in our study was 2.8 per annum for every 10 000 persons. However, these figures may not be directly comparable as there was an interval of 8 years between the Waikato study and ours.

The Ministry of Health in New Zealand began to collect statistics on the use of seclusion in 2006. According to the 2009 report, review of these indicates significant differences in the frequency and duration of seclusion used when different district health boards are compared.6 This report showed that between 1 January and 31 December 2008, covering the majority of time of the present study, 6424 patients spent time in New Zealand adult mental health units and 16% (1023) of these individuals were secluded, substantially more than the 9.1% in this investigation. Nationally, most episodes of seclusion lasted less than 3 hours.

There is a significant variance of seclusion data across district health boards but there have been no studies investigating why this is so. However, it seems likely that the introduction of psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs) in certain areas where these have been provided contributes to a lower frequency of seclusion. One of us (J.B.) now works in Wellington where there is a PICU and seclusion in this unit is a relatively rare event. The nearest PICU to Invercargill is in Dunedin, which is 110 miles away. This unit has high occupancy rates and transporting disturbed patients (a 2- to 3-hour journey) is logistically difficult. The lack of provision of a PICU could possibly be a factor contributing to a higher rate of seclusion in Southland than would otherwise be the case.

Our finding that more males than females were secluded parallels reports from others.Reference El-Badri and Mellsop5 Patients of Maori and European nationality were more likely to be secluded than those of the New Zealand Pākehā (White) population who had been brought up in New Zealand. Our figures regarding the rate of seclusion of Maori patients are similar to those in the study carried out in Waikato, in the North Island of New Zealand, where 20% of all Maori patients admitted were secluded as opposed to 11% of patients of Pākehā origin.Reference El-Badri and Mellsop5 A quarter of the continental European patients were secluded in our study. The Southland Mental Health Unit catchment area includes Queenstown, which attracts a large number of European tourists. Three of the four Europeans secluded had developed manic illnesses and had a pre-existing bipolar affective disorder.

Diagnosis was related to the practice of seclusion. Most patients who were secluded had a psychotic illness, particularly schizophrenia, mania and schizoaffective disorder. Similar findings were noted in an earlier study.Reference El-Badri and Mellsop5 However, over 20% of the patients had a non-psychotic disorder, including substance misuse, adjustment disorder and conduct disorder.

The time of year when seclusion occurs has not been studied in great detail. In this small study there were no significant differences in the rates of seclusion according to the season. Similarly, in a study of violent episodes by psychiatric in-patients no seasonal change was noted.Reference Noble and Rodger7 In a larger investigation carried out in a forensic psychiatry unit in Finland there were significantly more seclusion episodes in the summer months, starting in July and continuing until November.Reference Paavola and Tiihonen8

With regard to the day of the week when seclusion was initiated, fewer episodes occurred on a Sunday. It is likely that seclusion is less commonly implemented at weekends becauseofthereductionofformalprogrammesofactivityand education at this time and because more patients are on leave during this period. This finding has been noted by others.Reference Noble and Rodger7,Reference Rangecroft, Tyrer and Berney9

On examining the actual episodes of seclusion, agitation, involving threats of assault to staff, patients or property, was recorded as the reason for seclusion in 75% of the episodes, whereas actual physical assault occurred in only 20% of the episodes. This latter figure compares with a higher frequency of 45% for assault in the Waikato study.Reference El-Badri and Mellsop5

The evening shift is the time of day when seclusion is most frequently implemented and half of all the episodes occurred between 16:00 and midnight. In the Waikato study a virtually identical figure (52%) was noted for the evening shift.Reference El-Badri and Mellsop5

It is generally agreed that seclusion should be used for the least amount of time possible. The average duration reported by previous studies varies widely. The duration of seclusion in this study (median 17 hours) is long, but is similar to the period of seclusion noted in the Waikato investigation, where the median time of seclusion was 14 hours.Reference El-Badri and Mellsop5 In earlier studies on the length of time of seclusion episodes, Soloff & Turner reported a median duration of 2.8 hours (mean 10.8, range 10 minutes-20 hours) in the USA,Reference Soloff and Turner10 and Thompson found a median duration of 4.3 hours (range 10 minutes-25.5 hours) in the UK.Reference Thompson11 These two investigations were carried out over two decades ago. More recent studies show a considerable reduction from these figures,Reference Fisher12,Reference Smith, Davis, Bixler and Lin13 after programmes were developed to reduce periods of isolation. The duration of seclusion episodes recorded in both our study and that from the Waikato study is considerably longer than in these investigations and suggests a different attitude to treatment approach.

In New Zealand, as is probably the case elsewhere, the length of time spent in seclusion is based on clinicians’ assessments and the patients’ response to intervention. Since deinstitutionalisation, patients in psychiatric hospitals have become more acutely ill and therefore are more challenging to treat.Reference Keski-Valkama, Sailas, Eronen, Koivisto, Lönnqvist and Kaltiala-Heino14 This is consistent with international evidence suggesting an increase of violence in psychiatric hospitals.Reference Flannery, Juliano, Cronin and Walker15 It would therefore be expected that there would be an increase in the risk for being secluded or restrained when receiving treatment in a psychiatric hospital. Perhaps surprisingly this is not the case. According to some commentators, the reason why the duration of seclusion has decreased recently is because stricter regulations regarding this practice have been enforced.Reference Currier and Farley-Toombs16,Reference Donovan, Plant, Peller, Siegel and Martin17 If this assumption is correct, tighter regulation on the use of seclusion in New Zealand could well lead to a reduction in the time spent in isolation.

With regard to factors associated with the use of seclusion, international studies suggest reasons for variation include differences in seclusion practice, the availability of intensive care and low-stimulus facilities, staff factors, geographical variations in prevalence and severity of mental illness, use of sedating psychotropic medication, and data collection or analysis errors.Reference Livingstone18 The reasons for the period of seclusion being prolonged in Southland may include reduction of staff numbers, particularly at night,Reference El-Badri and Mellsop5 and inadequate management. The undoubted fact of reduced night-time supervision may explain to some degree the longer period of seclusion experienced by patients secluded during the evening shift.

What may be more important is the treatment received when in seclusion. Our assessment of the treatment given showed that when treatment was perceived as inadequate the period in seclusion was correspondingly prolonged. The reasons for this could include changes in psychiatrist supervision during the long supervision, an inclination not to change the existing medication regime, concern about giving large doses of sedative drugs and inadequate knowledge of psychopharmacological and management techniques of the psychiatrists involved. It seems evident that more careful attention to prescribed guidelines would be of benefit.

This study supports the findings of an earlier study carried out in New Zealand showing that the duration of seclusion, when carried out in acute psychiatric in-patient units, is longer than in other countries. This investigation suggests that more appropriate management of patients while in seclusion could contribute to shorter periods of time in isolation.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Mental Health In-patient Unit at Southland Hospital for their assistance in contributing to this study and Dr Jonathan Tyrer, Genetic Epidemiology Group, Department of Oncology at Cambridge University, UK, for helpful statistical advice.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.