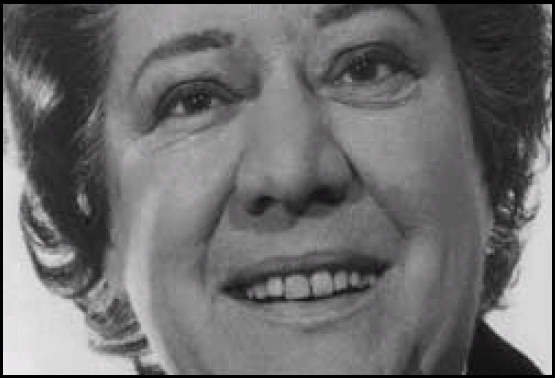

A leading historian of British mental health services, an inspiring critic of mental health and social policy

Kathleen Jones, who was always called Kay, has died aged 88. She was the leading historian of mental health services, who wrote three great studies: Lunacy, Law and Conscience (1953), Mental Health and Social Policy (1960) and Mental Hospitals at Work (1962, with Roy Sidebotham). She was one of the few responsible for establishing teaching and research in social policy in British universities, and founded the department of social policy and social work at the University of York in 1965. By the time she retired in 1988, the department had become one of the largest and most successful of its kind in Britain.

Born in London, Kay was the daughter of a lorry driver and a dinner lady. She was brought up on a large council estate and won scholarships to the University of London (based in Oxford during the war), where she edited the student paper Oxford Socialist. She queued to buy the Beveridge Report, which proposed social welfare reform, when it was published in 1942.

Her fascination with mental health provision and policy began when her husband Gwyn Jones became chaplain to a large institution in Lancashire in the mid 1940s. She expressed anxiety about the gap between theory and practice, and between policy in Whitehall and delivery in the local community or on the ward. She wrote about how mental health policy was implemented; about how organisational structures help or hinder innovation; and how best to support staff through often turbulent changes.

In 1961, Enoch Powell, then Minister of Health, announced the closure of large psychiatric institutions. Kay thought this was nothing short of asset-stripping by the National Health Service - mental health patients were to be returned to local authorities in large numbers, with inadequate funding, no research base and no staff retraining. She campaigned against the plan with a mass of publications and speeches. She became known as ‘Jones the Mental’. Powell sent her handwritten letters expressing his annoyance. She tore up his ‘weasel words’ and carried on.

Her work during the 1960s was sometimes viewed as defending psychiatric institutions, although she believed that the old Victorian hospitals were well past their sell-by date. She wanted smaller, modern mental health units with well-researched and resourced community services that broke down the barriers between health and social services. Five years after Dr Franco Basaglia's Pschiatricia Democratica drove through legislation in Italy (1978) to abolish mental hospitals and introduce ‘alternative structures’, Kay set off with Alison Poletti on a safari the length of the Italian peninsula to assess the consequences. Their influential reports, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry (‘Understanding the Italian experience’, 1985; ‘The “Italian experience” reconsidered’, 1986), scotched exaggerated claims of success and asked why they had found such ready and uncritical acceptance in Britain. Italian mental hospitals were reappearing in disguise and the ‘freeing of psychiatric patients’ without extensive and expensive substitute services had clearly proved a failure.

It was a blessing as well as a formidable challenge to have Kay Jones closely watching myself and colleagues developing services in York to replace Naburn and Clifton hospitals. Her follow-up study of long-term patients discharged in York (1985) improved our plans and the health authority was shamed into returning funds released from our mental hospital sites that had ‘somehow’ leaked into general hospital budgets.

She continued to write on mental health and, although she was neither a social worker nor a psychiatrist, she served as chair of the Association of Psychiatric Social Workers and was elected an honorary fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. She was a devout member of the Church of England, serving on two lengthy national commissions: the Archbishops’ Commission on Church and State and the Archbishops’ Commission on Marriage. She was a member of Lord Gardiner's committee on Northern Ireland (terrorism and human rights), which involved visiting republican detainees in the Maze prison. She was delighted that she contributed to the end of detention without trial. She also served as chair of the Mental Health Act commission dealing with patients’ complaints all over the north of England.

In retirement she continued to be productive, writing a textbook, The Making of Social Policy in Britain (2001). Her interests had moved on to the saints and, after editing The Poems of St John of the Cross (1993), she contributed to Butler's Lives of the Saints (1999) and wrote Women Saints (1999) as well as Who Are the Celtic Saints? (2002). Her final work was Challenging Richard Dawkins (2007), a combative reply to aggressive atheism. Combative was perhaps her hallmark. She was a fighter.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.