‘In the construction of [asylums], cure and comfort ought to be as much considered as security, and I have no hesitation in declaring that a system which, by limiting the power of the attendant, obliges him not to neglect his duty, and makes his interest to obtain the good opinion of those under his care, provides more effectively for the safety of the keeper, as well as for the patient, than all the apparatus of chains, darkness and anodynes’. Reference Tuke1

Samuel Tuke writing in 1813 identified the main components of psychiatric security: chains (physical), darkness and comfort (procedural), the good opinion of those under his care (relational) and care and anodynes (the effects of treatment). Reference Tuke1 Two hundred years later, spending on secure and high-dependency psychiatric services accounted for 18.9% of National Health Service (NHS) adult mental health spending in 2009/2010 and has increased by 141% in the past 7 years. 2 Although accounting for almost a billion pounds of NHS expenditure annually, there has been relatively little research on the clinical assessment of security needs, the importance of different aspects of security or even basic definitions of security. Assessing a patient's need for secure psychiatric services is a key competence in forensic psychiatric training. 3 Detention at an appropriate level of security has been national policy since the Reed Report (1992) Reference Reed4 and re-stated in the Bradley Report (2009). Reference Bradley5 A validated method of describing and comparing patients’ security needs and the security provided by secure psychiatric services is therefore an essential precursor to progress in this field. For individual patients, a proper understanding of their full range of security needs will allow a correct initial placement and appropriate progress through the various levels of security towards their potential discharge into the community.

Levels of security in England and Wales have, overtime, become defined with four levels: high, medium, low and open. The high-security hospitals, Ashworth, Broadmoor and Rampton in England and The State Hospital at Carstairs in Scotland, provide the highest level of security. Even within the high-security hospitals there were great variations in the levels of security provided leading to the second Ashworth Inquiry (1999) Reference Fallon6 and the subsequent ‘Tilt Review’ of security (2000) Reference Tilt7 that culminated in a uniform and detailed security regime being applied across all the English high-security hospitals. This process, although increasing the standards of physical and procedural security, was criticised as neglecting relational security, partly as it was conducted by prison service personnel with little clinical input. Reference Exworthy and Gunn8 Medium secure services were established, at varying rates, across England and Wales following the Butler Report (1975). 9 Although an NHS design guide for medium secure services 10 was produced in 1993, this provided little detail on security and was not widely known of or followed than practise. More definitive standards for medium secure services were produced only in July 2007; 11 the work of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Centre for Quality Improvement and the medium secure standards group was also influential in developing clinical standards for medium security. Reference Tucker12 Low secure and psychiatric intensive care services were included in the National Service Framework Policy Implementation Guides 13 in 2002 (recently revised) but, although exhorting good practice in multidisciplinary working, gave little concrete guidance on the detail of security provision. Interestingly, Department of Health publications on relational security ‘SEE THINK ACT’ 14 and the ‘Best Practice Guidance Specification for Adult Medium-Secure Services’ 11 contained no references to previous publications or academic literature. Although there are now standards of some description for all levels of security, these differ greatly in style, content and purpose.

Some aspects of security are very easy to define, such as the height of a perimeter fence or wall, whereas definition of other items such as managing media interest is much more complicated. There will inevitably be a different balance of needs between different services; the requirements of an open rehabilitation ward being very different to a high secure admissions ward. Different patient groups will also have different profiles based on, for example, physical and intellectual abilities or type of offending such as predatory sexual offences or violence against a close relative.

Following the establishment of medium secure services in the late 1980s and early 1990s it became apparent that many patients required longer admissions than were initially envisaged (18-24 months) and that some remained in high security for many years or even decades as regional secure units were reluctant to admit them. A series of audits and needs assessments were published in the mid- to late-1990s addressing this issue but with widely differing estimates of the number of beds needed in different types of facility (such as Murray et al, Reference Murray, Rudge, Lack and Dolan15 Shaw et al, Reference Shaw, McKenna, Snowden, Boyd, McMahon and Kilshaw16 Bartlett et al, Reference Bartlett, Cohen, Backhouse, Highet and Eastman17 McKenna et al Reference McKenna, Shaw, Porceddu, Ganley, Skaife and Davenport18 and Pierzchniak et al Reference Pierzchniak, Farnham, De Taranto, Bull, Gill and Bester19 ). We (M.C. and S.D.) were commissioned to undertake a similar needs assessment for the Trent Region Secure Services Commissioning Team. On reviewing the existing literature it was clear that a lack of definition for security was one of, if not the, major reason for the disparity in the estimates. The Security Needs Assessment Profile (SNAP) was devised to provide more robust scientific assessment of individual patients’ security needs rather than relying on individual or panel clinical judgements. Reference Collins and Davies20 The SNAP covers the three well-established domains of physical, procedural and relational security (Appendix 1). These domains are subdivided into a number of separate items: 4 physical, 14 procedural and 4 relational. Each item is then subdivided into four operationally defined points from zero (no need) to three (high need) (Appendix 2). These correspond to different levels of security need: open, low, medium or high. The levels of need do not all correspond directly to levels of secure provision, for example high levels of relational skills can be provided in a unit with very little physical security. These domains, items and operationally defined points were based on our clinical experience and widespread consultation; we were employed within Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust, which provided high, medium and low secure and open psychiatric units.

Appendix 1 The 22 Security Needs Assessment Profile items (with original items in brackets if revised)

| Domain 1 - Physical Security |

| Item 1 - Perimeter |

| Item 2 - Internal |

| Item 3 - Entry |

| Item 4 - Facilities |

| Domain 2 - Procedural Security |

| Item 5 - Patient supervision (Nursing intensity) |

| Item 6 - Treatment Environment (Environment) |

| Item 7 - Searching |

| Item 8 - Access to potential weapons and fire-setting materials |

| Item 9 - Internal movement |

| Item 10 - Leave |

| Item 11 - External communications |

| Item 12 - Visitors |

| Item 13 - Visiting children |

| Item 14 - Media interest (Media exposure) |

| Item 15 - Detecting illicit or restricted substances (Access to illicit substances) |

| Item 16 - Access to alcohol |

| Item 17 - Access to pornographic materials |

| Item 18 - Access to information technology equipment |

| Domain 3 - Relational Security |

| Item 19 - Management of violence and aggression |

| Item 20 - Relational skills (Relational nursing skills) |

| Item 21 - Response to nursing interventions and treatment programme |

| Item 22 - Security Liaison (Security intelligence and police liaison) |

Appendix 2 An example of a dimensional scale: External communications (item 11)

| Criterion |

| (3) All incoming mail is examined as is a proportion of outgoing mail. All telephone calls are to accredited people following their written consent using personal identification telephone systems. No incoming calls are accepted and a proportion of calls are randomly recorded and checked. |

| (2) Incoming mail is opened in the presence of staff and the number of received letters may be recorded in a log. There may be some discreet monitoring or supervision of telephone calls and certain numbers may be withheld upon the identification of any nuisance/abusive calling. |

| (1) Monitoring of communications unusual and usually related to specific risk indication. |

| (0) No restrictions on external communications. |

The resulting instrument was used in an audit of male patients in high, medium and low secure units, with a focus on planning for long-term services. This early development, including an assessment of SNAP's psychometric properties, has been published. Reference Collins and Davies20 Having developed SNAP within the Trent region, in this current study we sought to validate it by carrying out a national (England) survey of secure psychiatric services. The SNAP is used by commissioners, clinicians and services across England and Wales. 21 It helped inform the development of definitions of secure services in Scotland Reference Crichton22 and a new medium secure unit in Northern Ireland. Reference McClean23 The instrument has also received critical recognition, being reproduced in an international collection of risk assessment and management reference materials. Reference Collins, Davies, Webster and Bloom24

This study sought to verify the content validity of SNAP, i.e. does the instrument cover all the relevant areas of security needed to manage risk in secure psychiatric services. The study had four further aims.

-

(a) Undertake a national survey of the aspects of security provided by secure services in England with reference to the 22 items included in SNAP.

-

(b) Refine SNAP in the light of the findings of the survey, primarily in terms of better definitions of the items on each of the scales but also, if appropriate, including additional items.

-

(c) Provide a better understanding of the aspects of security provided by secure services in England and describe these in terms of core aspects and variations for different types of services.

-

(d) Gain views of clinicians and managers on the potential usefulness of the current version of SNAP.

The chair of the Trent Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee confirmed that the research was a survey of existing practice and did not require ethical approval.

Method

Secure units within England were identified from a variety of sources including the Secure Services Directory, 25 personal contacts and commissioning networks. Units were contacted and asked to participate in the study; no unit refused, although there were some delays due to local research and ethical procedures. A security liaison nurse was seconded to the project (C.A.) who visited each of the units having made contact with a senior member of staff responsible for security.

Each unit was inspected by the investigator. This involved an examination of the physical security provided. The policies and procedures relating to security were also reviewed. The most important aspect was an in-depth discussion with members of staff, particularly the senior member of staff responsible for security, usually a nurse manager. This interview began by explaining the structure of SNAP and the aims of the study. The security provided by their service was described in detail for each existing item rather than scored against the existing item definitions. Respondents were specifically asked whether any important areas of security had been omitted from SNAP, or whether any items were redundant. The unit was scored against the existing item scores at the time of the visit.

Following the completion of the survey the item scores were reviewed against the detailed descriptions of security provided by the services and amended to better represent the security provision across the county, differences between low and medium security, and clarify areas of confusion. Units were rescored against the revised criteria.

A follow-up survey, in the form of a seven-item questionnaire with responses on a five-point Likert scale, was sent to the contact person who was asked to complete it themselves and pass a copy, along with a copy of the SNAP manual, to another senior professional at the unit. A reminder letter was sent after 3 weeks and a follow-up telephone call made.

Results

Thirty-five units participated in the survey. This included: 1 high-security hospital (Rampton); 22 NHS medium secure (including 2 for learning disability); 4 private medium secure; 5 NHS low secure; 2 private low secure; 1 psychiatric intensive care units. Although a larger survey had been intended, the assessments proved to be more time consuming than envisaged, with unit visits and interviews often being spread over 2 days. Delays in receiving research approval also resulted in fewer units being visited. Although variations between units were found, we reached data saturation at 26 units, i.e. no new information was generated after this.

Although there were many helpful suggestions for amendments to item definitions and points on the scales, no new items were identified and no items found to be redundant confirming the 22-item structure of SNAP. The units surveyed provided services for female patients and patients with intellectual disabilities confirming the utility of SNAP across all populations in secure psychiatric services.

Detailed descriptions of each item as provided by each unit were made. These were assimilated into revised item definitions representing clinical practice across the 35 units. The changes in an individual item definition are illustrated by item 22, security liaison (Box 1). Having initially been written from a high-security perspective this item had focused too much on police liaison and criminal contacts. We had also neglected the emerging specialty of security liaison clinicians, and the increased integration of security into daily care planning.

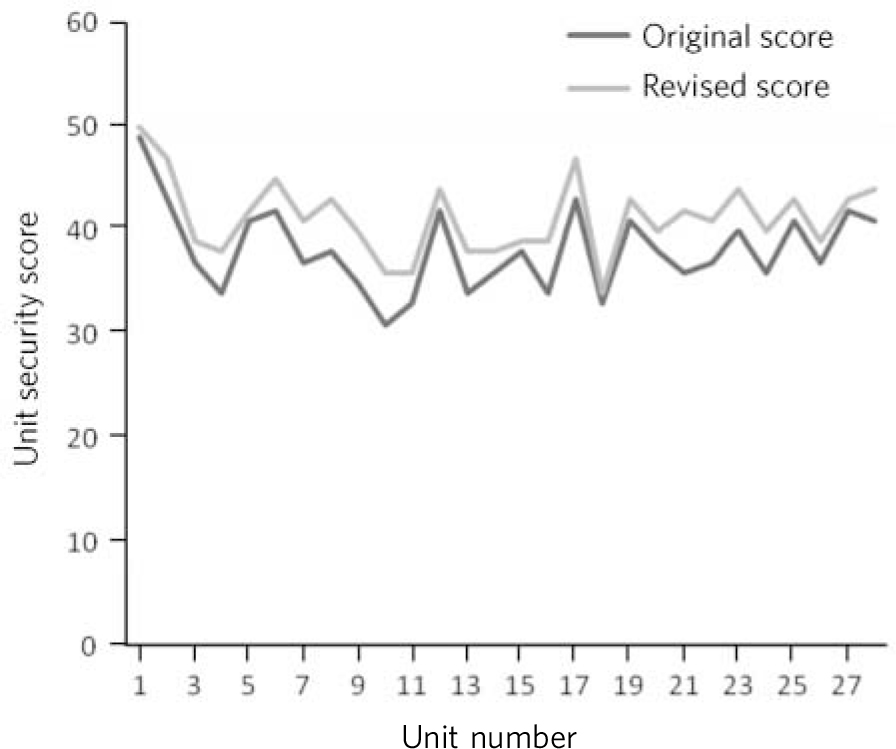

The security provided by individual units was rated using the original version of SNAP at the time of the visit. Following the revision the units were re-rated. Not all units’ scores changed but a summary of changes in total scores for those that did is included in Fig. 1. There was very little change in relational scores, with only two units shifting one point upwards. Most units that moved scores only move one or two points upwards for physical and procedural security scores with the largest movement being four points. Changes in overall mean security scores and standard deviations are shown in Table 1.

FIG 1 Changes in unit scores between the original and revised Security Needs Assessment Profiles.

TABLE 1 Average Security Needs Assessment Profile (SNAP) scores

| Mean score (s.d.) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Security level | On previous version | On revised version |

| Medium | 39.6 (3.7) | 42 (3.2) |

| Low | 31.1 (5.1) | 34 (2.5) |

Without exception all scores that did change moved in an upward direction, giving us confidence that our revisions had been effective and achieved a more representative picture (had scores moved in a downward direction this would have meant that our ordinal descriptors had become too strict and would be unrepresentative of actual provision). A general downward trend in standard deviation scores indicates increased reliability with the new version.

Box 1 Item 22: Security liaison

Original descriptor: Security intelligence and police liaison

(3) Patient has a network of highly organised criminal contacts which may present significant risks with reference to: organised escape attempts, receipt of illicit and dangerous items, hostage-taking attempts or intimidation (of staff, patients or previous victims). These risks exist either internally during or after visits or other methods of external communication, or externally on necessary movements from the secure area. High degree of police liaison required which may include national and international crime offices.

New descriptor: Security liaison

(3) The patient requires dedicated security liaison staffandprocedures in place to gather and analyse security information to prevent incidents (for example, organised escape attempts, receipt of illicit and dangerous items, hostage-taking attempts or intimidation of staff, patients or previous victims). Security intelligence plays an integral role in care planning and delivery and continuous assessment of at risk situations, e.g. movement from the secure perimeter.

We sent out 70 questionnaires to the participating units with a 53% return rate. Responses were on a five-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Potential usefulness of the Security Needs Assessment Profile (SNAP) (n = 37)

| Question: SNAP could be useful | Agree, n (%) | Strongly agree, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| For providing a structured assessment of security needs for patients? | 26 (70) | 8 (22) |

| As part of a pre-admission assessment? | 23 (62) | 12 (32) |

| As part of a pre-transfer assessment? | 25 (67) | 9 (24) |

| To the multiprofessional team for CPA/treatment planning meetings? | 20 (54) | 6 (16) |

| In resolving differences of opinion, regarding appropriateness of placement? | 19 (51) | 8 (22) |

| For security training of staff? | 20 (55) | 13 (35) |

| For audit/clinical governance? | 23 (62) | 4 (11) |

CPA, care programme approach.

Discussion

Although the basic dimensions of security, physical, procedural and relational, have been recognised for many years there has been no systematic attempt to more closely define what each of them entails. There have been various documents attempting to address these issues but there is no agreed framework to describe security provision or need. The Health of the Nation Outcome Scale for Users of Secure and Forensic Services (HoNOS-secure), Reference Dickens, Sugarman and Walker26 developed as part of the HoNOS suite of outcome scales, does address patients’ need for security and risks of harm across all security levels. It does this by adding seven items to the 12 core HoNOS items. 27 These cover the three core domains of security: building security to prevent escape (physical); a safely staffed living environment (relational); need for risk management procedures and escort on leave beyond the secure perimeter (both procedural). The HoNOS-secure also assessed aspects of risk: harm to adults or children; self-harm; risk to individual from others. Although an important advance in the evaluation of forensic psychiatric services, as an outcome scale, it does not attempt to provide the detailed of aspects of security assessed by SNAP.

Main findings

The current study, by surveying security provision over a large number of units at varying levels of security, provides a robust framework to further work in this area. The 22 items in SNAP have been shown to cover all the identifiable domains involved in providing secure psychiatric services. Individual item scores were revised, sometimes substantially, as expected, to make them more representative. It is to be expected that there will be further changes in definition of levels and content over time. (The current version of the SNAP Manual 4.1 2007 is available from the authors on request, a revised version is anticipated following the publication of planned Department of Health revised guidelines on low secure services).

The SNAP has some utility for ‘open’ in-patient settings or even specialist hostels managing forensic patient groups that may, for example, provide higher levels of supervision, higher levels of staff skills in risk assessment, drug and alcohol testing and escort patients routinely into the community. As its focus is on security needs in terms of managing risk to others, it would have only a limited role in psychiatric service where the predominant concern is risk to self.

The main limitation of the study is that, as a survey, it records existing practice and expert opinion which is not itself backed up by a coherent body of empirical research. It may therefore magnify existing errors and restrictive practices, although hopefully by providing acceptable definitions it will stimulate more rigorous examination of security provision and application.

Security provision is constantly evolving and any instrument needs to evolve accordingly. For example, there has been a greater preoccupation with security in society in general over recent years; almost all public buildings now have some form of entry controls be they open psychiatric wards, school playgrounds, courts or council offices.

The clinicians who responded to the survey were very positive about the utility of SNAP in providing a structured assessment of security needs. Although for the majority of patients a routine clinical and risk assessment will enable a decision on the appropriate level of security to be reached in difficult or contested cases, a more structured approach would be very useful. The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 allows for appeals against the level of security a patient is detained in; colleagues in Scotland have used the SNAP framework in relation to these decisions. Reference Crichton22 A measure of security needs that can be replicated is very useful in advancing research, audit and clinical governance in relation to secure psychiatric services.

Implications

The validation of the content of SNAP, in terms of items covered and item definitions, by a national survey of secure psychiatric provision represents an important step in critically examining such services and in understanding the needs for and uses of security in psychiatric care.

Funding

This study was funded by the NHS National R&D Programme on Forensic Mental Health. The initial development of SNAP was funded by the Forensic Services Specialist Commissioning Team, North Nottinghamshire Health Authority.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Helen Barrs and Gemma Eitel-Smith, Research Assistants on the initial project, the Security Liaison Department at Rampton High Security Hospital and Arnold Lodge Medium Secure Unit, Leicester. We are very grateful to all the units who cooperated with this study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.