In 1965, Ian Hunter, the director-general of the London Commonwealth Arts Festival, travelled throughout the Commonwealth to compile a programme showcasing performing and visual arts from all corners of the former empire. Within six months, Hunter took more than fifty flights, however, for the impresario, this was not mere talent scouting, but rather international cultural diplomacy: ‘I was trying to discover what the different countries wanted to send in order to create the best impression.’Footnote 1 Australia would send the Sydney Symphony Orchestra conducted by Dean Dixon, Sir Bernard Heinze, and Joseph Post to give the first concert at the Royal Festival Hall. The musical works to be presented at the festival included John Antill's Corroboree and Peter Sculthorpe's Sun Music I.Footnote 2 Representing itself to the mother country, the Australian government was not concerned to present an affinity with the other colonies whose Indigenous cultures would be represented at the festival. Instead, it aimed to put Australia's achievements and cultural character in dialogue with English creative traditions. Indeed, it was orthodoxy, not distinctiveness, that preoccupied Australian governments of the early 1960s.

In this article, I contextualize this decision by juxtaposing two music and dance events presented to Sydney audiences in the lead up to the Commonwealth Arts Festival. The first is the ballet suite Burragorang Dreamtime composed by John Antill and choreographed by Beth Dean for the Pageant of Nationhood in March 1963. The second is the Aboriginal Theatre toured by the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust (AETT) in December 1963. The Aboriginal Theatre was proposed by the AETT for the Commonwealth Festival, but subsequently rejected. I suggest that there is a direct relationship between the promotion of non-Indigenous composers as representatives of Australia's cultural achievements, the denial of that right of self-representation to Aboriginal composer/musicians, and the foundation of an Australian musical style reliant on the very Indigenous traditions that it repudiates.

This analysis follows Patrick Wolfe's theorization of ‘the logic of elimination’ that characterizes settler colonial nations where the colonizing forces have come to stay, with no plans for withdrawal. As Wolfe and Lorenzo Veracini contend, in these settler colonial contexts ‘the native repressed continues to structure settler-colonial society’ and ‘settler acquisition of entitlement as indigenous’ corresponds to an ‘indigenous loss of entitlement as such’.Footnote 3 In drawing on Wolfe's and Veracini's framing, I am also sensitive to critiques of settler colonial theory. Like Tim Rowse, I aim to recognize the ‘Indigenous heterogeneity’ that has arisen out of Aboriginal people's responses to settler colonial efforts at elimination as well as the ‘postcolonizing’ framework offered by Aileen Moreton-Robinson for understanding the processual work of embodied indigeneity ‘that continues to unsettle white Australia’.Footnote 4 Though the particular story I tell here is framed around entanglement of settler and Indigenous Australians, I also acknowledge the potential suggested by Shino Konishi for Indigenous stories to be celebrated as ‘extra-colonial histories’.Footnote 5

Notwithstanding the inventive and resilient responses of Indigenous musicians and composers in Australia, the promotion of Australian art music composition has sought to replace Aboriginal culture in direct ways, which remain unacknowledged in critical musicology. The appropriative tradition made most famous by composers John Antill and Peter Sculthorpe relied on representations of Aboriginal culture for its distinctiveness and cultural prestige, even while the rightful proponents of those cultures were denied opportunities to perform their own traditions and cultural innovations, and while their mobility was restricted by a mix of policy and direct government intervention.

Performing settler replacement: Antill and Dean's ‘Aboriginal ballets’

It is no surprise that John Antill's Corroboree should be one of the works chosen for the Sydney Symphony Orchestra's programme at the festival. Corroboree quickly became canonical in conceptions of Australia's emerging musical voice following its first performance by visiting conductor Eugene Goossens in 1946. Using as the title a word from the Australian Aboriginal Dharug language of the Sydney region signifying a gathering in music and dance,Footnote 6 Corroboree seemed to have realized the vision of music journalist, critic, and editor Thorald Waters who, a decade earlier, had called for the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) to foster a ‘national creative style’.Footnote 7 Waters's article coincided with Antill's appointment to a position at the ABC and after the premiere of Corroboree, the ABC supported Antill to study orchestration in London, promoting him to music supervisor for New South Wales (NSW) on his return.Footnote 8 In 1951, a full production of the ballet was realized when Rex Reid was commissioned to choreograph Corroboree, and it toured the nation as part of the celebrations of the Jubilee of Australia's Federation.Footnote 9 New choreography was commissioned for Queen Elizabeth II's 1954 visit, this time by American choreographer Beth Dean, who had spent the preceding four years touring the nation with her Dances of the World, establishing a reputation as an expert in Aboriginal dance.Footnote 10 This 1954 Corroboree production began a creative collaboration that would see Antill and Dean produce a number of new ballets staged in Australia and abroad to represent Australia and its history and culture.

The collaborations of Antill and Dean are emblematic of how settler colonial replacement of Aboriginal people was performed to the nation throughout the mid-century during Australia's Assimilation era.Footnote 11 In the years leading up to the Commonwealth Festival, their work had repeatedly been chosen to represent Australia to visiting monarchs. A set of two ballets was commissioned for the visit of Princess Alexandra of Kent in 1959 – ‘Legend of the Boomerang’ and ‘Legend of the Waratah’ presented as the suite Burragorang Dreamtime. When Queen Elizabeth II made her second trip to Australia in 1963 to coincide with celebrations of the 175th anniversary of British settlers’ arrival, the suite featured again in a commemorative Pageant of Nationhood.Footnote 12

The Pageant of Nationhood was staged at the Sydney Showground by the Arts Council of NSW. Burragorang Dreamtime was intended to depict life before the invasion of settlers by using ‘an Aboriginal concept about how the world began’ and preceded a re-enactment of Caption Phillip's landing onto the Dharawal Country of the Gweagal clan, and his greeting by ‘aborigines’.Footnote 13 The ballet was danced by an all non-Indigenous cast dressed in brown body stockings adorned with white decorative paint. Beth Dean performed the lead role. The script for the Pageant of Nationhood shows that this spectacle depicted Aboriginal occupation of the continent as prehistory – a dreamtime that would recede as the outside world encroached. Caption Phillip's landing scene was prefaced by the following narration:

The Dreamtime of the aborigines is about to come to an end. The great Spirit heroes fade into the dim past. The everyday poetry of the aborigine is soon to become in fact – only a Dreamtime.

Out from the endless sea – out from the mists of the world appeared a new Spirit image – the white man.Footnote 14

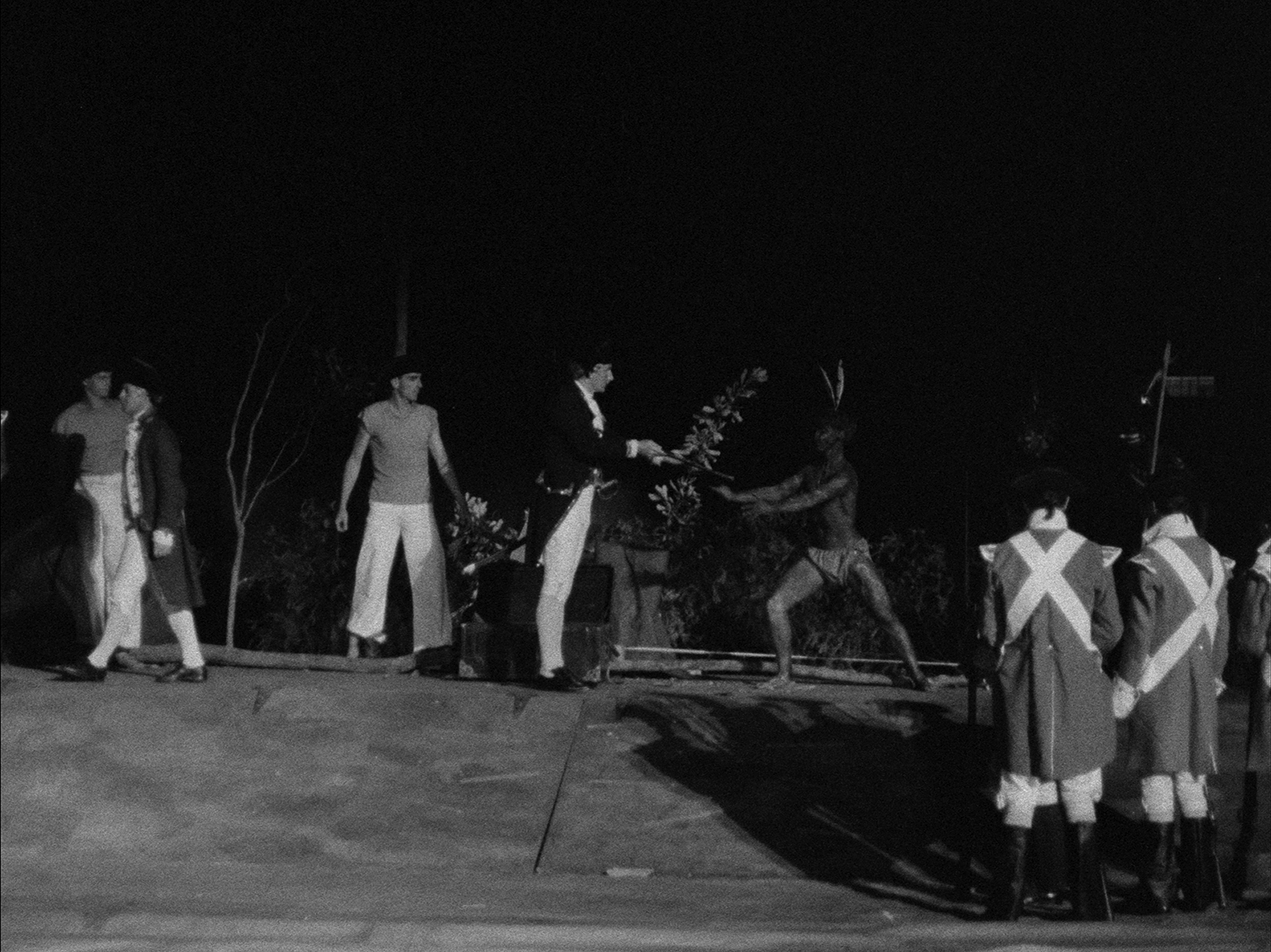

As the ballet concluded, the actor (Peter Potok) playing Governor Phillip emerged. Dancers from the ensemble who had just completed the ballet played the role of Aboriginal people confronting, and ultimately retreating from, the invading British (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Still from Pageant of Nationhood: Australia's 175th Anniversary: New South Wales Celebration. From National Film and Sound Archive, Title: 56886.

Not only did the placement of Burragorang Dreamtime in the Pageant of Nationhood's narrative enact an attempt at replacement, so too were the residents of the Burragorang Valley being displaced through the march of nationhood. The ballet's narrative was drawn from a Gundungurra story about the birth of the first waratah flower – a symbol appropriated as the official state flower for New South Wales.Footnote 15 In 1960, the Burragorang Valley, west of Sydney, where the ballets’ legends of the Waratah and Boomerang originated, was flooded to create the Warragamba Dam – the major drinking water supply for the Sydney region. As the NSW Aboriginal Welfare Board's magazine Dawn exclaimed:

There is no help for it. The Valley's fate was written on the day when Phillip founded his city on Sydney Cove. Burragorang is only 60 miles away from Sydney's heart; its vast catchment area (3,383 square miles) makes it the most eminently suitable permanent storage for the city's water supply. It now must die.Footnote 16

By the mid-1950s, all residents, Aboriginal and non-Indigenous, had been relocated out of the area that the Gundungurra people had populated for thousands of years.Footnote 17 Dean and Antill's Burragorang ballets had first been performed on 11 September 1959, before the valley was flooded, but after people had been ejected.Footnote 18

Rather than engaging with the displacement of Aboriginal people, artists such as Dean and Carell responded to these events by romanticizing stories of erasure into representative performances, in which the replacement of Aboriginal people by the settler colony was re-enacted, and in which performing cultures were also literally replaced. Instead of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander dancers performing a corroboree for the Queen, as occurred in towns as varied as Wagga Wagga, Toowoomba, Townsville, Cairns and Whyalla during both the 1954 and 1963 visits, Dean and the dancers and Antill and the orchestral musicians performed Aboriginality with little regard for the continuing existence of Aboriginal performers attempting to find new contexts for representing their own music and dance at home and overseas.Footnote 19

The Pageant of Nationhood production received a lukewarm review in which the Sydney Morning Herald’s music critic Roger Covell suggested that it was successful overall, even if it ‘went on a little too long’, if the aboriginal ballet scenes were ‘inevitably disjointed’ and if on the whole it was ‘diffuse and often pointless’.Footnote 20 Indeed, though none of Antill's subsequent works attained the level of praise and widespread appreciation with which Corroboree had been greeted, Antill received frequent new commissions throughout the 1950s and 1960s, especially when the state sought a representation of Australian culture. Covell comments that Antill was ‘a kind of musician-laureate for state occasions’.Footnote 21 In interviews for Dean and Carell's biography, Antill recalled that:

after Corroboree everybody thought of me as a ballet writer. Many stories and commissions came my way. Ballet seemed to be the thing expected of me and it kept pushing the symphonic works into the background. I had been a symphonic man all my life.Footnote 22

In David Symons's musical biography of Antill, he notes that the 1961 Black Opal marked the end of Antill's new works on Aboriginal themes. The choreographer of the ballet, Dawn Swane reportedly asserted that Antill was reluctant about this project for fear of being typecast as a composer of ‘Aborigiana’.Footnote 23 By contrast, Aboriginal-themed ballet remained central to Beth Dean's professional profile after early praise of her 1950 Dances of the World productions marked it out as her specialty. Dean continued to pursue opportunities to choreograph ‘Aboriginal ballets’ beyond the early 1960s, though these were no longer collaborations with Antill.Footnote 24

The Pageant of Nationhood ballets that seemed so disjointed to Covell imagined the key legends of Australia's nationhood – an Aboriginal past, and a modern, non-Indigenous present. Unlike other re-enactment events that brought Aboriginal people into the nation's capitals from elsewhere (sometimes under duress), Dean and Antill represented this Aboriginal past without any involvement of Aboriginal people at all, a practice they had each repeated since 1946 (Antill) and 1950 (Dean) in numerous productions.

Later in the commemorative year of the Pageant of Nationhood, in December 1963, Antill and Dean attended the performances of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust's Aboriginal Theatre. According to Dean, the impact of this on Antill was profound:

This was far different from anything Antill had seen before. It was not the rather impromptu ‘tourist version’ by Aborigines who had not been living a tribal life for many years, sometimes generations, as they survived on the outskirts of towns. John was thrilled. One may wonder what Antill might have done if he had experienced this kind of Aboriginal music in his early days, rather than on his 60th birthday.Footnote 25

To follow Dean's line of enquiry, we might wonder whether the Pageant of Nationhood would have proceeded along the same narrative line of replacement of Aboriginal people by the new arrivals, had the Aboriginal Theatre toured in December 1962 rather than 1963.

‘Among the greater innovations in world theatre’: the AETT's Aboriginal Theatre

The Aboriginal Theatre, a new production by the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust, was toured to capacity audiences in a two-week run at Newtown's Elizabethan Theatre in Sydney with one-week at St Kilda's Palais Theatre, Melbourne in December 1963. Each night's show began with a fire-making performance, in which the audience saw a darkened stage gradually illuminate with sparks and fire and the smell of burning leaves, created by Frank Artu Dumoo, Skipper Anggilidji, and Barney Munggin. The performers, who had travelled down from the Daly Region of the Northern Territory, from Yirrkala in northeast Arnhem Land and from the Tiwi Islands, then presented a series of works devised by each group.Footnote 26 The danced performances were alternated with solo didjeridu performances, though publicity materials depicted a quartet of didjeridus (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Publicity shot for the Aboriginal Theatre – performers depicted are likely Garmali, Rikin, Yangarin and Bokara, ‘Didgeridoo players of the Aboriginal theatre: Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust’, A1200, L46022, National Archives of Australia.

The origins of the Aboriginal Theatre can be found in music composed, practised, and performed by ancestors of the performers for thousands of years in continuous but also vibrant and changing traditions across the extremities of the north of the Australian continent. Some of these performance traditions came to wider public attention in the North Australian Eisteddfod, begun in 1957 and including, from the early 1960s, the categories didjeridu solo with singing sticks accompaniment, Aboriginal interpretative group and solo dance, and didjeridu and songmen duet. The Aboriginal performances in the eisteddfod were quickly recognized as some of the highest quality and most interesting of the event. In July 1963, the AETT's executive director, Stefan Haag, travelled to Darwin to view the Aboriginal performing arts categories. In consultation with Harry Giese, Northern Territory (NT) director of welfare, and Ted Evans, chief welfare officer, groups of performers were chosen from the three communities.Footnote 27

Subsequently, logistics and planning for the tour occurred through a series of negotiations between Haag, for the AETT, and Giese and Evans, for the NT Administration. That the NT Administration was the intermediary for sourcing performers for the Aboriginal Theatre is indicative of the reach of the welfare regime in managing the lives of Aboriginal people at this time. This is particularly evident in the AETT's rebuffing of approaches that circumvented this established framework. At least one direct approach was made to Stefan Haag by Sam Passi, chairman of council, Murray Island, Torres Strait, who sought to promote the dances of his own community as suitable for the Aboriginal Theatre.Footnote 28 Haag seems to have been unreceptive to the direct line to the performers that Passi offered, preferring his established relationship with NT Welfare Officers.Footnote 29 It is certain that unsolicited offers were often rejected by the AETT, but these particular rejections also seem to indicate the structural confines within which Aboriginal dance and music was supported by the AETT in the 1960s.

The Aboriginal Theatre's programme and publicity materials give some indication of how the season was pitched to the Australian public. Though the performers ranged in age from teenagers to men in their sixties, the programme asserted that the Aboriginal Theatre would present the ‘oldest Australians’. Yet the Aboriginal Theatre aimed also to innovate – the programme asserted that allowing audiences to experience ‘the fantasy and nobility of the age-old aboriginal spirit, places it among the greater innovations in world theatre in 1963’. Of the hundreds of ensembles and productions being supported by the AETT and overseen by Haag, the Aboriginal Theatre seems to have been one of his pet projects, and Haag would attempt to revive the idea to tour the Aboriginal Theatre in Australia and abroad repeatedly in subsequent years. The minutes of an AETT board meeting in 1964 show that members discussed whether the show should be altered to be more theatrical and less ‘anthropological’. Stefan Haag argued that the theatricality of the work could be enhanced without compromising the ‘authenticity’ of the performances.Footnote 30

The shows aimed simultaneously to engage those interested in Aboriginal performance from an ethnographic and/or historical perspective and those creating and producing new works of modern dance, music and visual art on Australian stages. In the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, anthropologists frequently acted as cultural brokers between performers, the arts sector, and the media. The list of invited VIPs for the Aboriginal Theatre's Sydney performances included a range of university and museum anthropologists and academics, including Frederick McCarthy from the Australian Museum, A. P. Elkin, Alice Moyle, Arthur Capell, and William Geddes from the University of Sydney, among a shorter list of prominent individuals from the arts sector including dance critic and choreographer Beth Dean, New South Wales Conservatorium of Music's director Sir Bernard Heinze, Arts Council of Australia president Dorothy Helmrich, and visual artist Russell Drysdale, alongside government ministers including the chief secretary and minister for tourism (also responsible for Aboriginal welfare in NSW) the Honourable C. A. Kelly. Several of the invited anthropologists, including Australia's most prominent anthropologist and expert on Aboriginal cultures at this time, A. P. Elkin, not only attended, but wrote to Stefan Haag in praise of the performance in the days afterwards.

Artistically, most agreed that the show was a great success, even if it posed financial challenges for the AETT.Footnote 31 Haag had championed the project, not only as an early initiative in his role as executive director of the AETT, but also as artistic director of the show itself (he was criticized from some quarters for trying to juggle both roles).Footnote 32 Looking at footage and listening to recordings of the Aboriginal Theatre today, family and community relatives of some of the performers agree that the dances and songs performed were done properly – even if the Tiwi mourning songs were being publicly demonstrated instead of ritually performed for a particular recently deceased person. As senior Tiwi woman Jacinta Tipungwuti told me while listening to a recording of the Tiwi songs in the 1963 shows, ‘they had that strong culture! And they left that for us … generation to generation’.Footnote 33

Though the AETT Board's characterization of the performances as ‘anthropological’ suggests a reluctance to regard Aboriginal performing arts as ‘modern’, this was not necessarily how the work was received by Sydney and Melbourne audiences, and by critics embedded in the music and dance scene. The Sydney Morning Herald’s music critic Roger Covell, who, a few years later, wrote the field-defining book for contemporary Australian western art music – Australia's Music – reviewed the 1963 shows:

The unique entertainment that brought authentic music, dancing and mime from the great artistic traditions of the Australian aborigines to the stage of the Elizabethan Theatre, Newtown … and brought them in the person of the inheritors of these traditions: the aborigines themselves…

It is hard to know which to admire more: the untroubled assurance, the truly professional aplomb, with which these 45 artists have transplanted their ceremonies from the bare earth arenas of their tribal grounds to a spotlit city theatre, or the sympathetic integrity with which Stefan Haag has put the resources of Western stagecraft at their disposal…

There is no need to pretend that this is an equivalent of any other kind of theatre. This is an experience to tell your grandchildren about.Footnote 34

Covell's reaction to the Aboriginal Theatre, which contained a certain revelatory sense of having discovered something that one had not known was there, is replicated in some of the correspondence sent to AETT's director Stefan Haag, congratulating him on the production. Like Covell, audiences seemed suddenly to recognize the Aboriginal Theatre's performances as, in fact, not old Australians at all, not re-enactments of a culture that existed before Captain Cook's visit, which was now gone, but rather, vital, living, and continually transforming culture.

Beth Dean (choreographer of Burragorang Dreamtime) in her role as Daily Telegraph dance critic also praised the professionalism and intensity of the performers in her review of the event, adding that the show was ‘strong, exciting and intensely interesting fare. Everyone should see it’. Dean also claimed that the performance did not live up to some of those she and her husband had witnessed on Country (during their visits to Aboriginal communities in Australia's north). Though she had built a career on performing Aboriginal dances in the theatre of the ‘white man’, she characterized the Aboriginal dancers’ efforts to do so as lacking the authenticity of a fireside performance:

If the performance lost anything last night, and it did, it was that the Aborigine could not be stimulated by his own environment, challenged by his own competition as he dances around the fire at night …The Aborigine last night could not be free to give his best in the narrow, tradition-bound, proscenium-arched theatre of the white man.Footnote 35

Philosopher, public intellectual and sometime theatre reviewer Alan Ker Stout found himself surprised by the show, which he had approached with low expectations.Footnote 36 Stout was impressed enough to recommend that the Aboriginal Theatre would be an appropriate touring show to represent Australia overseas:

The success of this whole presentation suggests that in it the Trust may have discovered a dramatic experience that is both uniquely Australian and exportable. It speaks a universal language and has a universal appeal. Since it survived unharmed the drastic move from the scrub of Arnhem Land to the theatre stage of Melbourne and Sydney, what is to prevent its further transplantation to London, Vienna or Paris.Footnote 37

Indeed, Stout was not the only one to imagine that the Aboriginal Theatre could represent Australian culture internationally, and opportunities would soon arise. In 1965, the AETT proposed the Aboriginal Theatre as a potential representation of Australian culture on the programme of the Commonwealth Festival in London. To Haag's disappointment, this proposal was rejected.

This was not Haag's first attempt to facilitate an international tour; a US tour by American promoter Sol Hurok proposed for November–December 1965 did not go ahead out of concern for how the Aboriginal performers would cope with winters in the United States, as Ted Evans wrote to Stefan Haag:

Permission for this company to leave Australia must be obtained from the Department of Native Affairs.

As you know they are one of the most primitive people on earth added to which they are used to a year round temperature of 90°F therefore there may be some opposition to their leaving the country for the colder northern climate.Footnote 38

In decision making about the London Commonwealth Festival, the ‘welfare’ of the performers was, however, not the key motivator. Rather this was a question of Australia's national identity on an international stage. Specifically, the decision was about showing the Commonwealth how Australia had developed its own voice in European genres. As Stefan Haag related to Ted Evans:

government circles have expressed the doubtful wisdom of the aborigines being the major contribution to the Commonwealth Festival in that it would tend to suggest that there is no cultural achievement in Australia other than the indigenous one of the aborigines. Hence it was felt that initially at least preference should be given to orchestras and theatrical companies. A defensible point of view I think even though you and I and many others will be disappointed.Footnote 39

A range of cultural anxieties can be read in this statement, along with an eagerness to present a unified Australian identity, and one that mapped onto a European performance medium. Other settler colonies shared these preoccupations. New Zealand would send to the Commonwealth Festival the Christchurch Harmonic Choir of fifty voices, who would sing in Westminster Cathedral, while Canada would send French-speaking theatre companies and English-language ballet. Like Australian composers, Canadians had also developed representations of their First Nations traditions that appropriated culture while excluding Indigenous people. Radhika Natarajan suggests that Canada's Commonwealth Festival offering ‘affirmed the availability of First Nations and Inuit artistic production for white appropriation and excluded Canada's European immigrants and “visible minorities”, Asian and African ancestors, from the performance of Canadian nationalism’.Footnote 40

By contrast, colonies from which British colonizers had withdrawn but which still remained part of the Commonwealth took the opportunity to demonstrate the individuality of their creative talents at the festival – Pakistan would send the Khattak dancers, India its finest classical musicians led by Ravi Shankar as well as Kathakali dancers, Kenya would send the Embu Drummers, Ghana an orchestra of xylophones, flutes, and drums.Footnote 41 In total, 1200 performers travelled to England and the event ran for three weeks in a festival of multi-culturalism that Natarajan has characterized as ‘postimperial reengagement … that promised aesthetic equality through the acceptance of difference’.Footnote 42 Natarajan notes that in Britain, this embrace of cultural diversity sat uneasily alongside imperial nostalgia, but in Australia and in its representations at the festival, the possibility of multiculturalism was unrealized amidst anxiety about its cultural achievements.

In another international event in 1965, this time on Australian soil, the AETT's proposal for the Aboriginal Theatre to represent Australia had met with reluctant approval, this time alongside cultures of the greater Asia-Pacific region as part of the Pageant of Asia during the Sydney Trade Fair in 1965, rather than the British Commonwealth. But even then government reservations were tabled. H. Neil Truscott wrote for the Department of External Affairs:

there is a vast gap between the sophisticated songs and dances of the Asian peoples and those of the aborigines and Papuans, which, though of some merit and considerable interest, are primitive by comparison.Footnote 43

The kinds of Aboriginal dances selected for the Pageant of Asia reflected the scale of its production space, as Haag wrote to Giese: ‘the decorations of the desert tribes with stuck on feathers and high-peaked head dresses would, in my opinion, stand much more chance of getting across at such a distance’.Footnote 44 The show also featured several performers who would go on to prominent performing and recording careers in Australia and overseas, including David Blanasi and Djoli Laiwanga.Footnote 45

While for the Commonwealth Festival the performers of the Aboriginal Theatre were not deemed sufficiently representative of Australian culture, their artworks were. Collector Dorothy Bennett took what Harry Giese described as ‘a comprehensive exhibition of Aboriginal bark paintings and artifacts to the Festival’.Footnote 46 The Australian Government's concern about allowing living Aboriginal performers to stand for Australian culture evidently did not apply to disembodied art objects. The Bennett-Campbell Trust bark paintings were presented alongside those by non-Indigenous Australian painters Russell Drysdale and William Dobell. Paintings could not speak and give interviews about conditions in Australia in the way members of the Aboriginal Theatre might have been able to, especially those Yolngu artists who had recently used their paintings as political capital to protest Bauxite mining through the Yirrkala bark petitions of 1963.Footnote 47 Signatory to the petition Narritjin Maymuru's paintings had graced the Aboriginal Theatre's programme cover, and he performed in the ensemble's 1963 Melbourne and Sydney shows.

The inclusion of paintings but exclusion of live performers also demonstrates that resources to promote and support Aboriginal cultural practice were directly in competition with resources to exhibit European performance genres by non-Indigenous people. The 1965 Commonwealth Festival programming highlights this opposition poignantly in its selection of a representation of Australian culture that drew on notions of Aboriginality in Antill's Corroboree, and in the championing of Sculthorpe who would later go on to capitalize on this appetite for representation of Aboriginality devoid of Aboriginal people. By presenting orchestral compositions by non-Indigenous composers that represented a notion of Aboriginality in 1965, Australia could demonstrate its cultural achievement as distinct from Britain, but also as not only ‘the indigenous one’, differentiating itself from other British colonies in the Commonwealth whose native traditions had not been successfully replaced by hybridized European ones.

Representing itself to international audiences, the Australian government, through its choices of performing and visual arts actioned by its cultural bodies, sought to maintain a narrative of Aboriginal people as something old and past, not modern and continually transforming. Tangible, but static artworks were sent overseas – works standing in for the artists who had created them – but live performers were excluded from events such as the Commonwealth Festival in favour of non-Indigenous composers and performers who would represent Australia as a culture in dialogue with European modernity.

Australianist art music and reckoning with the past

The works performed by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in the 1965 London Commonwealth Festival remain significant in conceptions of Australia's art music history. Antill's Corroboree had premiered almost twenty years earlier, and Peter Sculthorpe would soon become Australia's most prominent national composer, with a reputation based on his creation of what some listeners think of as a uniquely Australian style. This evocative Australian style was characterized by techniques such as the use of Aboriginal song material, and of string instruments to imitate Australian birdsong. Sun Music I drew on Japanese Noh theatre traditions, rather than Australian ones, but in its integration of Japanese music into a European Classical format, its use of experimental notation and repetitive rhythms, the work was deemed to represent an emergent Australian cultural identity in a way that the Aboriginal Theatre's performances did not.

Though Sun Music I does not draw on Aboriginal music, in the early 1960s Sculthorpe was exploring ways to incorporate the sounds of Australia's First People into his compositions. Correspondence between Sculthorpe and ethnomusicologist Alice Moyle in 1963 indicates his attempts to procure ‘recorded didjeridu and bullroarer sounds as “background” to some film music’ he had recently composed (The Fifth Continent 1963).Footnote 48 In her reply, Moyle pointed out to Sculthorpe that the Australian bullroarer would be unsuitable given it was only used in ‘rare and secret ceremonies’, and so had seldom been recorded; she suggested he source commercial recordings of bullroarers from Papua New Guinea. Moyle then described a range of different didjeridu styles that could be relevant, depending on the musical context. In a revealing sign off, Moyle offered to discuss Aboriginal music further with Sculthorpe:

Whenever you come to Sydney I shall be glad to demonstrate to you the stylistic differences in Aboriginal music. And speaking for the few – very few – who are now engaged in probing into this strange and complex music I can only say that it is time Australian musicians themselves began to treat it with more knowledge and discrimination. Unless they do, the ABC will not.Footnote 49

Despite Moyle's invitation to a greater intimacy with the intricacies of Aboriginal musical style, Sculthorpe's use of melodic material from song recordings developed as formulaic rather than nuanced. Indeed, his response suggested he was not interested in the specifics, rather that the sounds were ‘merely to establish certain moods, & not illustrative in any way’.Footnote 50 A few key melodies derived from transcriptions or audio recordings of Aboriginal song were used as the basis of numerous compositions across Sculthorpe's career. Most frequently featured were two melodies, djilili (whistling duck) recorded by Elkin in Arnhem Land in 1949Footnote 51 and used (in some cases repeatedly in new arrangements for different instrumental combinations) in Sculthorpe's Port Essington (1974, 1977), Dua Chant (1978), Djilile (1986, 1990, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2008), and Kakadu (1988), and the ‘Maranoa Lullaby’ from the 1937 Australian Aboriginal Songs published by Loam and Lethbridge, used by Sculthorpe in Two Aboriginal Songs (1949), Into the Dreaming/For Cello Alone (1993, 1994, 1998), Maranoa Lullaby (1996, 2007, 2012), Lullaby (2003), and Requiem (2004).Footnote 52

Like many other composers including Alfred Hill, and later Ross Edwards, Sculthorpe's representation of Aboriginality tended towards the atmospheric, rather than the specific or the attentive to regional difference or formal structure. In an echo of Moyle's sentiments thirty years earlier, ethnomusicologist Catherine Ellis suggested in 1991 that

Very few composers have taken the trouble to examine the structural intricacies of Aboriginal music. They have preferred to look at the superficialities: a descending melody, a regularly repeated stick beat, a didjeridu-like sound.Footnote 53

Indeed, treating Aboriginal music with knowledge and discrimination, let alone a collaborative approach, has been something art music composers have come to very late, with a few recent examples suggesting a belated change of direction.Footnote 54

Sculthorpe's star continued to rise throughout the 1960s and 1970s and he retained the status of Australia's best-known composer until his death in 2014. Antill and Dean's creations are now rarely performed, even if Corroboree is almost universally recognized as a foundational moment in Australian art music.Footnote 55 However, the musical forms toured with the Aboriginal Theatre continue to enjoy a vibrant performance practice today, at least in their home communities (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 (Colour online) Wangga Singers at Kanamkek Yile Ngala Museum, Frank Artu Dumoo playing didjeridu (second from left) with (L–R) Ambrose Piarlun, Maurice Ngulkur, John Dumoo, Thomas Kungiung and Les Kundjil.Footnote 56 Photographer Mark Crocombe, c. 1990, with permission from Wadeye community.

Anne Boyd, Michael Hannan and, more recently, Jonathon Paget have addressed some of the ethical questions raised by the tying of Sculthorpe's compositional voice to an Australian sound characterized by use of melodies from recordings of Aboriginal song, titles and narratives drawn from Aboriginal traditions, and nature-imitating instrumental effects. And in the final two decades of his life, Sculthorpe himself responded to critics in several media interviews, and by changing his composition practice. However, in spite of the repeated attempts at intervention from a number of ethnomusicologists, Aboriginal people and others, Australian musicology has not reckoned with its role in the power structures of settler colonialism in which it is embedded.

Sculthorpe's response to the ethical questions raised by his use of Aboriginal melodies in the ‘sensitive cultural climate … in which the appropriation of any Indigenous material is regarded as something of a transgression’ was to assert that ‘with one exception, there is no direct borrowing in my work. The small number of chants to which I refer, are always transformed in one way or another.’Footnote 57 Making changes to his practice, he also formed an ongoing collaborative relationship with didjeridu virtuoso William Barton, allowing Barton considerable compositional license in new works such as his 2004 Requiem.

Works by Boyd, Hannan, and Paget have largely landed on the side of apologism for the appropriative work of Sculthorpe and his colleagues. Hannan focused on whether the melodies appropriated were recognizable in their new form, an approach that confines the ethics of this representation to the narrow terms of copyright law where recognizable similarity between the works is construed as an infringement of rights.Footnote 58 Boyd has tended to characterize cultural appropriation as a natural tendency for creative artists to draw on the richness of cultural materials available, or in her words: ‘The meshing of cultures is an inevitable consequence of positioning intellectual property in cyber-space.’Footnote 59 Paget has suggested that though Sculthorpe could be argued to have ‘subtly benefited’ from the prestige conveyed by his claim to Indigenous representation, his ‘true legacy’ may be found in the celebration of Indigenous cultures.Footnote 60

Conclusion

Australian art music has been largely unreflective on the roots of its cultural hegemony. The narrow definitions of misappropriation of melodic material captured in the thinking of these recent analyses does not consider the historical forces of the ‘continuing usurpation of indigenous space’ for which Wolfe has persuasively argued.Footnote 61 In spite of its ties to Europe, ‘Australianist’ art music emerged from the settler colonial nation of Australia, a country that has violently and brutally dispossessed Aboriginal people of land, stolen children from families and communities, destroyed language practices and punished people for attempting to continue performing culture. Aboriginal people have responded to these destructive efforts in inventive ways and their remarkable resilience means that ties to country, language, music and culture are now being revitalized, languages are being woken up, and painstaking work is reconstructing cultural practices and kinship ties. The arts world in its nurturing of creativity, culture and social connectedness may feel very distant from these histories of violence, but Australian musicology has not yet reckoned with these origins.

The examples given here have demonstrated that Australian art music has been associated not just in a vague sense with the settler colonial project of silencing and erasure that Patrick Wolfe and Lorenzo Veracini have shown to be a structural characteristic of settler colonial nations, but rather Australian art music composers have been the direct beneficiaries of systemic moves to claim the right to represent Aboriginal culture, and have filled the silence created by the denial of this right to Aboriginal musicians. In demonstrating this, I suggest that in order to truly reckon with its past, Australian art music needs to historicize and contextualize its current practices and the privilege on which they are built.Footnote 62