1. Introduction

According to the desire-satisfaction theory of well-being, your life goes well to the extent that your desires are satisfied. More precisely, how well your life is going (i.e., how high you are in welfare or well-being) is determined by what desires you have, how strong those desires are, and which of them are satisfied or frustrated: the more satisfied desires you have and the stronger those desires are, the better off you are (other things being equal), whereas the more frustrated desires you have and the stronger those desires are, the worse off you are (other things being equal). A desire is satisfied just if its object obtains, and it is frustrated otherwise.

The desire theory faces various objections. According to one objection, it implies that if you can either satisfy an existing desire of yours or replace it with a new desire of equal strength and satisfy the new desire, then from the point of view of prudence or self-interest, you should be neutral between the two options. But that judgment seems counterintuitive: it is more plausible that, prudentially speaking, you should prioritize desires that you currently have over new desires with which you could replace them. This is the problem of prudential neutrality (Dorsey Reference Dorsey2019). Another objection is that there are ‘remote’ desires – ones whose objects seem so unrelated to your life that their satisfaction seems unable to affect your well-being (Heathwood Reference Heathwood2006). Examples of such desires include a desire that an ill stranger be cured, a desire that the number of atoms in the universe be prime, a desire that Napoleon's favorite color was blue, and a desire that people living centuries from now flourish. It is not clear how the desire-satisfaction theory can, in a principled way, deem a person's remote desires irrelevant to their well-being. This is the problem of remote desires.

In this article, I argue that desire theorists can adopt a unified strategy for responding to those two problems. The strategy is to look closely at the psychologies of the relevant agents and to uncover desires that are hidden in the sense that they are easy to overlook when these agents are first described. In the problem of prudential neutrality, the hidden desires are a variety of desires such as a desire to retain the desires that are central to one's identity, a desire not to have one's psychology changed artificially, and a desire to live a meaningful life. In the problem of remote desires, the hidden desire is a desire to know whether one's desires are satisfied. Once we have a more complete and realistic view of the psychologies of the relevant agents, these two problems are revealed to be less serious than they first seem: without modifying the standard version of the desire-satisfaction theory, we can solve the problem of prudential neutrality and give a better response to the problem of remote desires than has so far been developed.

2. The problem of prudential neutrality

Just as we can talk about what one ought to do from the point of view of morality and what one ought to do all things considered, we can also talk about what one ought to do from the point of view of prudence or self-interest – that is, what one prudentially ought to do. Intuitively, what one prudentially ought to do is a function of the strengths of one's prudential or self-interested reasons, as opposed to one's moral reasons or one's reasons of other kinds. In the problem of prudential neutrality, we are concerned with judgments about what the agent prudentially ought to do and with the strengths of the agent's prudential reasons. The following example from Dorsey illustrates the problem:

Faith: Faith is a highly regarded Air Force pilot who has long desired to become an astronaut. She has the physical skill, the appropriate training, and has been looked on as a potential candidate. At time t, she has the choice to undergo the last remaining set of tests to become an astronaut or take a very powerful psychotropic pill that would have the result of radically, and permanently, changing her desires. Instead of preferring to be an astronaut, she could instead prefer to be a highly regarded, but Earth-bound, Air Force pilot. (Dorsey Reference Dorsey2019: 161)

It will simplify our discussion to assume that, for whatever reason, Faith currently has no desire to be an Air Force pilot, and that taking the pill would altogether remove her current desire to be an astronaut and replace it with a desire to be an Air Force pilot. With that in mind, three things about this case are worth making explicit. First, if Faith were to undergo the last remaining set of tests, she would become an astronaut, so her existing desire to be an astronaut would be satisfied. Second, if she were to take the pill and thereby acquire a desire to be an Air Force pilot, this desire would be satisfied because she already is an Air Force pilot. Third, this counterfactual desire to be an Air Force pilot would be exactly as strong as her actual desire to be an astronaut is. Intuitively, Faith prudentially ought to undergo the last remaining set of tests to become an astronaut instead of taking the pill. However, desire theorists seem unable to accommodate this. After all, on their view, the extent to which a satisfied desire contributes to one's welfare is proportional to its strength. Since the actual desire to be an astronaut and the counterfactual desire to be an Air Force pilot are equally strong, and since other things are presumably equal, desire theorists seem to have to say that Faith prudentially ought to be neutral between undergoing the last set of tests and taking the pill because each option would leave her equally well off as the other. This prudential neutrality seems problematic.Footnote 1

Dorsey's solution to this problem appeals to different ways of thinking about what we have prudential reasons to do. To understand this solution, we must familiarize ourselves with two pieces of terminology that he introduces. The first piece of terminology is ‘prudential ordering’. A prudential ordering is ‘a rank-ordered – to the extent possible – list of goods that would benefit a person p at a time t were these particular goods to obtain’ (Dorsey Reference Dorsey2019: 159, his emphasis). On the desire-satisfaction theory, the items on your prudential ordering are objects of your desires (e.g., apples and oranges, if you desire them), and these items are ranked by the strength of your desires (e.g., apples are ranked higher than oranges if you desire apples more strongly than you desire oranges). The second piece of terminology is ‘welfare score’. A person's welfare score is how high or low in welfare that person is, and it is determined by ‘the presence or absence of welfare goods for the person at the relevant times’. On the desire-satisfaction theory, your welfare score is determined by the facts about your desires and their satisfaction or frustration, in such a way that the more satisfied (frustrated) desires you have and the stronger those desires are, the higher (lower) your welfare score is, other things being equal.

Dorsey argues that for the problem of prudential neutrality to arise, we must assume that the strength of a prudential reason to φ is proportional to the welfare score you would get if you were to φ. As I indicated above, desire theorists seem to have to say that Faith would have the same welfare score regardless of whether she undergoes the last set of tests or takes the pill. Dorsey's thought is that, from the claim that the two actions would give Faith the same welfare score, we would get the claim that Faith prudentially ought to be neutral between the two actions only if we assumed that the strength of a prudential reason to φ is proportional to the welfare score one would get if one were to φ. But Dorsey rejects precisely that assumption. He thinks that, on the desire-satisfaction theory, the strength of a prudential reason to φ instead depends on whether you would obtain things that are actually on your prudential ordering, and on where these things are located on your prudential ordering. On this view, Faith has stronger prudential reason to undergo the last set of tests than to take the pill because while being an astronaut is on her prudential ordering (given that she desires this), being a pilot is not (given that she doesn't desire this).

It would be beyond the scope of this article to explore all the details of Dorsey's proposal.Footnote 2 Let me simply explain why I don't believe it to be a sufficiently good solution to the problem of prudential neutrality. By rejecting the assumption that the strength of a prudential reason to φ is proportional to the welfare score you would get if you were to φ, his solution has the implication that you cannot have prudential reasons to change your prudential ordering, even when changing your prudential ordering would give you a higher welfare score than not changing it would. As he puts it:

In changing one's future prudential orderings, one necessarily does not respond to facts about what is good, because this action (taking the pill, etc.) simply grants the status of good to particular states of affairs. At best, changing one's future prudential ordering is simply aprudent: it is not the sort of action for which prudential reasons could count in favour of or against. (Dorsey Reference Dorsey2019: 169, his emphasis)

But as I will now argue, in some cases, we do have prudential reason to change our prudential ordering. Suppose that, as someone who has never had Burmese food before and who likes Japanese food, you more strongly want to have Japanese food than you want to have Burmese food. However, if you were to try Burmese food, you would love it so much that you would want it much more strongly than you would want Japanese food. Intuitively, given that the desire you would acquire for Burmese food if you were to have it is much stronger than your current desire for Japanese food, and given that you would therefore be much higher in welfare having Burmese food than you would be having Japanese food, you have at least some prudential reason to have Burmese food and thus some prudential reason thereby to change your prudential ordering.Footnote 3

Consider another example. Suppose that you want to become a violinist rather than an engineer, but you have no talent in music. If you were to try to become a violinist, you would have a very difficult life: you would have very low self-esteem, you would struggle to make ends meet, etc. Suppose also that you are really talented in engineering. If you were to try to become an engineer, you would come to be fairly well off: you would be happy, you would be able to support yourself financially, etc. Given that you would have a much higher welfare score if you were to try to become an engineer than you would if you were to try to become a violinist, it seems that you do have some prudential reason to replace your desire to become a violinist with a desire to become an engineer, and to thereby change your prudential ordering.

The intuition that you can have prudential reasons to change your prudential ordering is perhaps most compelling in cases in which, whereas it is impossible to satisfy one's existing desires, it is possible to replace them with satisfied desires. Consider a person who strongly wants to be taller than he actually is. This desire unavoidably gives him desire frustration, since there is no way in which he can change his height. If he could desire being exactly as tall as he actually is, that desire frustration would be replaced by desire satisfaction, and he would be much better off. Especially in light of the fact that his actual desire is not only frustrated but unavoidably so, it is plausible that he has prudential reason to change it and to thereby change his prudential ordering.

By arguing that the strength of a prudential reason to φ does not depend on the welfare score you would get if you were to φ, Dorsey commits himself to the implausible view that there cannot be any prudential reasons to change your prudential ordering, even when doing so gives you a higher welfare score than not changing it. We should therefore hope for a better solution to the problem of prudential neutrality.

3. The problem of remote desires

Sometimes people have desires whose objects seem so unrelated to their lives that their satisfaction seems unable to affect their well-being. Call these remote desires (Heathwood Reference Heathwood2006). Parfit presents the problem of remote desires in the following passage:

Suppose I meet a stranger who has what is believed to be a fatal disease. My sympathy is aroused, and I strongly want this stranger to be cured. We never meet again. Later, unknown to me, this stranger is cured. On the Unrestricted Desire-Fulfillment Theory, this event is good for me, and makes my life go better. This is not plausible. We should reject this theory.Footnote 4

As I mentioned earlier, other examples of remote desires include a desire that the number of atoms in the universe be prime, a desire that Napoleon's favorite color was blue, and a desire that people living centuries from now flourish, etc. Whether these desires are satisfied does not seem to affect the person's well-being, but it is unclear that desire theorists have a principled and plausible way to exclude such desires.

Overvold (Reference Overvold1980: 10n.) argues that the only desires that increase well-being when satisfied are those whose objects cannot obtain unless the desiring agent exists at the time when the objects obtain. On this view, Parfit does not benefit from the satisfaction of his desire that the stranger be cured because the stranger can be cured even if Parfit doesn't exist at the time when the stranger is cured. But as Heathwood (Reference Heathwood and Fletcher2016: 141) observes, this view is too restrictive, since it cannot account for cases where a person does seem to benefit even though the satisfaction of her desires does not depend on her existing at the relevant time. Suppose that I am just an ordinary fan, so whether the sports team I support wins the championship does not depend on my existing when they win. Nevertheless, if the team wins the championship, I seem to benefit.

Similar to Overvold, Parfit (Reference Parfit1984: 494) and Griffin (Reference Griffin1986: 21) attempt to solve the problem of remote desires by restricting the range of desires that are relevant to well-being. Parfit argues that only desires that are ‘about our own lives’ are relevant to well-being, but even Parfit himself admits that it is unclear which desires are about our own lives and which desires are not. Griffin suggests that only desires whose objects involve one's central ends are relevant to well-being, where one's central ends seem to be what one strongly desires. But we can imagine cases in which the desires we want to exclude are held very strongly, and thus would not be excluded on Griffin's view.

Heathwood (Reference Heathwood2006, Reference Heathwood and Fletcher2016) proposes that desire theorists should appeal to an awareness requirement according to which the satisfaction of a desire does not benefit a person unless they are aware of it. This proposal can get around the problem of remote desires because the agent whose remote desires are satisfied is often unaware of the satisfaction of their remote desires. Parfit does not benefit when the stranger is cured because he is not aware of the fact that the stranger is cured. If Parfit were aware of it, he would benefit. This seems to be the right thing to say. This proposal also accommodates the fact that I can benefit from the satisfaction of desires whose objects can obtain at times at which I don't exist (e.g., the desire that the sports team win the championship).

There are different ways to incorporate an awareness requirement into a desire theory of welfare. One way is to introduce the awareness requirement and jettison the requirement that the desire actually be satisfied. Another way is to introduce the awareness requirement and keep the requirement that the desire actually be satisfied. But the awareness requirement cannot give us a satisfactory solution to the problem of remote desires. For as I will now argue, there are serious problems with every desire theory that includes this requirement.

Subjective Desire Satisfactionism (SDS) (Heathwood Reference Heathwood2006) represents the first way of incorporating the awareness requirement. On this theory, what is intrinsically good for you is not the actual satisfaction of your desires but the subjective satisfaction of your desires (i.e., believing that you are getting what you want), and what is intrinsically bad for you is not the actual frustration of your desires but the subjective frustration of your desires (i.e., believing that you are not getting what you want). Although SDS can avoid the problem of remote desires, it cannot make sense of why life is not going so well for a deceived businessman who falsely believes that people around him love and respect him and who wants them to love and respect him (Lukas Reference Lukas2010: 17). This is a familiar problem for hedonism. According to hedonism, what makes a person's life go well is having a favorable balance of pleasure over pain. Hedonism cannot make sense of why it is not prudentially good for you to live a life like that of the deceived businessman. SDS faces the same problem because, like hedonism, it ultimately takes well-being to consist in a person's mental states.

What I will call ‘Conjunctive Desire Satisfactionism’ (CDS) represents the second way of incorporating the awareness requirement. This theory requires both desire satisfaction and subjective desire satisfaction for benefit, and both desire frustration and subjective desire frustration for harm. On CDS, there is exactly one thing that is intrinsically good for you, namely, the combination of desire satisfaction and subjective desire satisfaction, and exactly one thing that is intrinsically bad for you, namely, the combination of desire frustration and subjective desire frustration. CDS does better than SDS insofar as it is able to explain why the life of the deceived businessman is not going so well. The deceived businessman's desire that people love and respect him, although subjectively satisfied, is actually frustrated. And since one of the requirements for benefit is unmet, he does not benefit.

However, there is a problem that both SDS and CDS face. On both theories, a desire can affect a person's well-being only if she has a belief about whether she is getting what she wants. This means that things that a person wants but does not have any beliefs about can never affect her well-being. This seems implausible. To see this, imagine two duplicates of the deceived businessman. One is the deceived agnostic businessman, who wants love and respect, doesn't get it, and doesn't have any beliefs about whether he gets it. His life is identical to the life of the deceived businessman, except that he suspends his judgment about whether he is loved and respected. The other duplicate is the lucky agnostic businessman, who also wants love and respect and does not have any beliefs about whether he gets it, but who, unlike the deceived businessman, is actually loved and respected. Intuitively, the life of the latter is better than the life of the former. However, SDS and CDS cannot make sense of this judgment because neither of the businessmen has any beliefs about whether they get what they want. Since each way of incorporating the awareness requirement into the desire-satisfaction theory has serious problems, I conclude that we should not appeal to this requirement to respond to the problem of remote desires.Footnote 5

Lukas (Reference Lukas2010) bites the bullet in response to the problem of remote desires. He claims that remote desires are relevant to well-being, but he tries to explain why they might mistakenly appear irrelevant. We have far fewer remote desires than non-remote ones, he argues, and our remote desires are typically far weaker than our non-remote ones. So overall, the satisfaction of remote desires does not benefit us that much when compared with the satisfaction of our non-remote desires. The reason why Parfit's desire seems irrelevant to his well-being is that the desire about the stranger is just one desire that is rather weak, so when this desire is satisfied, Parfit benefits only a little bit. Because the benefit is small, people might mistakenly think that there is no benefit at all.

I am sympathetic to Lukas's response but I find it insufficient. We can stipulate that Parfit likes to meet strangers, and every time he meets a stranger, he forms a strong desire about the stranger's life. And just as in the original story, Parfit never meets the strangers again, and his desires about them are all satisfied. It still seems that Parfit does not benefit much from the satisfaction of his remote desires, but if Lukas's response is all the desire theorist has, she seems forced to say that Parfit benefits a great deal. Lukas's response is on the right track, but it doesn't go far enough.

4. A unified strategy

I will now argue that both the problem of prudential neutrality and the problem of remote desires appear more serious than they really are because existing discussions of them have relied on incomplete and simplistic pictures of the psychologies of the relevant agents, from which some of these agents’ desires are missing. Once we identify these hidden desires, we can solve these problems or at least blunt their force significantly.

4.1 A Response to the problem of prudential neutrality

In Faith, the desire to become an astronaut is presumed to be the only actual desire of Faith's that is relevant to whether she prudentially ought to take the pill. I think that, in addition to this desire, Faith is likely to have a variety of desires that are relevant but hidden, in the sense that they are easy to overlook on the basis of how the case is described. These desires include a desire to retain the desires that are central to one's identity, a desire not to change one's psychology by artificial means, and a desire to live a meaningful life. If Faith has any of these hidden desires, then choosing to undergo the last set of tests to become an astronaut would satisfy not just the desire to become an astronaut but also some of the hidden desires, whereas choosing to take the pill would only satisfy the desire to be an Air Force pilot. Thus, if Faith has at least one of the hidden desires, she has stronger prudential reason to undergo the last set of tests to become an astronaut because that is the option that would make her better off. This solution therefore allows desire theorists to avoid claiming that Faith prudentially ought to be neutral between the two options.

When people perform thought experiments, they bring in their own way of thinking about the world and implicitly assume that agents in the thought experiments would think about the world in the same way. When people read about Faith, they think about what they would desire if they were in her situation and implicitly assume that she would have the same desires. As I will argue, people tend to have a desire to retain the desires that make them who they are, a desire not to change their psychology by artificial means, and a desire to live a meaningful life, and it is reasonable to assume that people are at least implicitly aware of these desires in themselves. In addition, I take it that desires can be merely dispositional, as most desire theorists would agree (Schroeder Reference Schroeder2015): if a person is disposed to act in ways that she believes will bring about p or is disposed to feel enthusiasm or attraction for p when thinking about p (or revulsion toward ~p when thinking about ~p), then she has a desire for p. So, as long as people have the dispositions that constitute the relevant hidden desires, they can be said to have these hidden desires. And as long as people are at least implicitly aware of these dispositions in themselves, they are at least implicitly aware of having these desires.

The first desire that people might attribute to Faith is a desire to retain desires that are central to one's identity. It is not true in general that whenever one has a first-order desire, one also has a second-order desire to retain that desire: you might want to eat potato chips without wanting to keep wanting this, for example. But we do have (and implicitly recognize ourselves as having) a special set of desires that we want to keep: the desires that shape our identity and make us who we are. A lifelong fan of the Boston Red Sox, for whom being a Red Sox fan is a core part of her identity, not only wants the Red Sox to win but wants to continue wanting this: she is disposed to feel unhappy at the prospect of losing this desire and to refrain from behaving in ways that she thinks would extinguish it. A person whose love of poetry figures prominently in his self-conception not only wants to read poetry but wants to keep wanting this, since he would, in an important sense, no longer be who he is if he were to stop wanting it.Footnote 6 Since Faith is described as having ‘long desired to become an astronaut’, and since people's long-held career aspirations are typically part of their identity, it is natural to suppose that Faith's desire to become an astronaut is central to her identity: if she were to lose this desire, then an important part of who she is would be gone. For this reason, it is natural to suppose that Faith desires to retain this desire.

The second desire that people might attribute to Faith is a desire not to change one's psychology by artificial means. We all go through natural psychological changes as we age and have new experiences, and we are usually not disturbed by these changes. When psychological changes are caused by pharmacological interventions or other artificial means, however, we do have a tendency to be disturbed by them – a tendency that is constitutive of a desire not to undergo psychological changes via such means. For example, you would not be concerned if you've come to appreciate classical music more and more because you've been hanging out with friends who play it for you, but you would be at least somewhat concerned if your appreciation for classical music were caused by a drug that you've been taking. Consider, too, our preferences regarding how mental illnesses are treated. If you were to have a mental illness that could be cured either by talk therapy or by taking pills that modify the chemicals in your brain, you would probably prefer the former cure to the latter even if the pills have no side effects. This is further evidence of our desire not to have our psychologies changed artificially. Whether such a desire can be justified and what it is for an intervention to be artificial in the relevant sense are, of course, interesting open questions. But what matters for our purposes is that this is a desire that can plausibly be attributed to Faith and that would clearly be frustrated if she were to take the pill.

The third desire that people might attribute to Faith is a desire to live a meaningful life. It is a familiar fact that people typically want their lives to be meaningful: they are disposed to be unhappy at the thought that their lives are meaningless, excited about the prospect of making changes that would make their lives more meaningful, motivated to make such changes, and so on. Kauppinen (Reference Kauppinen2012) gives a theory of meaningfulness that I find compelling. On this account, what we mean when we say that a person's life is meaningful is that it is fitting for the person to be proud of it or to be fulfilled by it, and it is fitting for others to be inspired by it or to admire it. The kind of life that warrants these feelings, according to Kauppinen, is a coherent life in which the person sets goals, makes efforts toward achieving them, and succeeds in achieving them. For example, a life in which a person comes from a disadvantaged background but, through her determination and hard work, comes to have a fulfilling career is a meaningful life. On the contrary, a life in which a person fails to achieve her goals or in which her goals come about due to sheer luck is not as meaningful. If we accept Kauppinen's theory of meaningfulness, then the life in which Faith becomes an astronaut is much more meaningful than the life in which she takes the pill and stays a pilot. In the former life, she aspires to become an astronaut, works hard toward achieving that goal, and finally becomes what she has long wanted to become. It is a life that is fitting for Faith to be proud of and for others to admire. In the latter life, Faith aspires to become an astronaut, works hard toward achieving that goal, but gives up on it at the last minute for no apparent reason. It would be far less fitting to be proud of or admire this life, so this life would be far less meaningful. The life in which she becomes an astronaut would better satisfy her desire to have a meaningful life.

Faith does not need to have all the hidden desires that I have just laid out to have stronger reason not to take the pill. Any one of them would suffice to break the symmetry between the two options. As long as it is plausible that Faith has at least one of those desires, desire theorists can plausibly say that Faith has stronger reason not to take the pill. Since the hidden desires that are likely to be present in Faith are also likely to be present in other cases that display the problem of prudential neutrality, my response is not just a solution to Faith but also a solution to the general problem of prudential neutrality.

One might object to my response in the following way. We can imagine that, for each of the hidden desires that Faith currently has, the pill would give her a ‘counter-desire’ of the same strength that would be satisfied if and only if she were to take the pill. If Faith desires to retain her desire for becoming an astronaut, then the pill would give her an equally strong desire to eliminate her desire to become an astronaut. If Faith desires not to change her psychology by artificial means, then the pill would give her an equally strong desire to change her psychology by artificial means. If Faith desires to live a meaningful life, then the pill would give her an equally strong desire to live a meaningless life. Since, for each hidden desire of Faith's that would be frustrated if she were to take the pill, taking the pill would give her a satisfied desire the value of whose satisfaction cancels out the disvalue of the frustration of the hidden desire, it might seem that my solution implies that, in this version of the case, Faith prudentially ought to be neutral between her two options. But intuitively, even in this version of the case, Faith prudentially ought to become an astronaut instead of taking the pill.Footnote 7

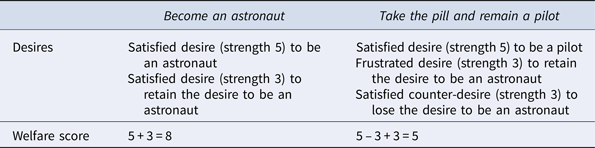

My response is that, far from conflicting with this intuition, my solution supports it. We can see this by comparing simple models of the two versions of the case. Suppose that Faith has only one hidden desire (the desire to retain her desire to be an astronaut, let's say), that this desire has a strength of 3, and that her desire to be an astronaut has a strength of 5. In that case, we can represent the original version of the case as follows – ignoring, for simplicity's sake, all of her other desires, which will be the same no matter which option she chooses.

By contrast, the new version of the case that we are now considering can be represented like this:

Although the disvalue that Faith would get from the frustration of her hidden desire is exactly canceled out by the value that she would get from the satisfaction of the ‘counter-desire’ that the pill would give her, and although this means that the difference in welfare between the two options is smaller than it is in the original case, it remains true that Faith would be worse off if she were to take the pill than if she were to become an astronaut. Thus, my solution has the intuitive implication that she prudentially ought to become an astronaut.

Of course, one could imagine another variation on the case, in which each ‘counter-desire’ caused by the pill would be twice as strong as the hidden desire to which it corresponds. In this version of the case, Faith would be equally well off regardless of which option she takes, so my solution really would imply that she prudentially ought to be neutral between the two options. Perhaps some would have the intuition that, even in this version of the case, Faith prudentially ought to become an astronaut. I admit that my solution cannot accommodate this, but this strikes me as an acceptably small bullet to bite. After all, even if we think that Faith prudentially ought to be neutral, we can hold that she ought, all things considered, to become an astronaut (e.g., because she has a strong reason of self-respect to take her existing commitments seriously). Perhaps what's intuitively plausible about this case is merely that Faith ought not to be neutral, all things considered – a judgment that my response leaves open.

My solution differs from Dorsey's and is immune to the objection that I made against it. Dorsey assumes that the welfare scores are the same in the two options because (except for what the crucial desire is about) all else is equal between the two options. His solution relies on the rejection of the view that the strength of a prudential reason to realize an option is proportional to the welfare score you would get if you were to realize that option. It is his rejection of this view that made his solution vulnerable to the objection that I raised. My solution is not vulnerable to the same objection because I don't reject this view. My solution relies on the claim that the welfare scores are not the same in the two options because not all else is equal between the two options, given that some hidden desires are satisfied in the first option but frustrated in the second.

My solution does not deliver the result that Faith necessarily has less reason to take the pill, regardless of whether she has hidden desires that would be frustrated if she were to take the pill but satisfied otherwise. It says that she has less reason to take the pill only if she has such desires. If Faith has no hidden desires favoring either option, then my solution says that she prudentially should be neutral between the two options because in the absence of any hidden desires, these two options would give her the same welfare score. This seems to me to be the right thing to say. Alternatively, if, instead of having any hidden desires that count in favor of her not taking the pill, Faith has desires that count in favor of her taking the pill (e.g., a desire not to retain desires that are central to her identity), then my solution says that Faith prudentially ought to take the pill because taking the pill gives her a higher welfare score than not taking the pill would. This also seems to be the right thing to say.

Those who are unconvinced should consider a case in which a small child can get one of two flavors of ice cream. She wants chocolate and could get it, or she could replace that desire with an equally strong desire for vanilla and get vanilla. Supposing (as is plausible) that she has no hidden desires favoring either option, it seems clear that she prudentially ought to be neutral between them, since both would make her equally well off. But stipulating that Faith has no hidden desires favoring either of her options makes her case exactly analogous to this one. We should therefore conclude that, if Faith has no such hidden desires, she prudentially ought to be neutral between her options. I suspect that any inclination to resist this conclusion is due to the fact that the relevant stipulation is psychologically unrealistic.

4.2 A Response to the problem of remote desires

The desire-satisfaction theory entails that Parfit benefits from the satisfaction of his remote desire that the stranger be cured, but this strikes many people as implausible. I think that, if we examine Parfit's psychology more closely, we are likely to find that there is a hidden desire that accompanies his remote desire: a desire to know whether his remote desire is satisfied.Footnote 8 It is clear from Parfit's example that this desire to know is frustrated. The frustration of this hidden desire decreases Parfit's well-being to a certain extent, and this might mislead us to think that Parfit does not benefit from the satisfaction of his remote desire. That is, Parfit does benefit from the satisfaction of the remote desire, but the benefit is counterbalanced to some extent by the frustration of the desire to know. If we are not thinking carefully enough, we might conclude that Parfit does not benefit from the satisfaction of the remote desire at all. This response generalizes to other cases of remote desires since these cases all involve a frustrated desire to know whether the remote desire is satisfied. A person who desires that the number of atoms in the universe be prime cannot know whether her desire is satisfied given our limited understanding of the universe. A person who desires that Napoleon's favorite color was blue cannot know whether her desire is satisfied given that nothing was recorded on the matter. And a person who desires that people living centuries from now flourish cannot know whether that desire is satisfied given that we have no way of knowing that.

In most cases, when we desire something, we also desire to know whether that desire is satisfied. For example, if you desire that you are healthy, then you probably also desire to know whether you are healthy: you are probably disposed to act in ways that you believe will give you this knowledge, disposed to feel anxiety when lacking this knowledge, and so on. Likewise, if you desire that your mother is happy, then you probably also desire to know whether she is happy. Besides being confirmed by ordinary cases like these, this principle is also supported by the observation that there is a tight connection between caring about something and wanting to know facts about that thing. As Jennifer Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2014: 233) puts it:

part of caring about X is caring what happens to X, and this in turn makes one want to know how things stand with X, what is happening in the vicinity of X, and so on. Indeed, to lack all concern for the facts about X (in the sense of lacking any desire to know these facts) is good evidence for a lack of concern about X.

If it is possible to desire something without caring about it, then these considerations cannot show that first-order desires are inevitably accompanied by second-order desires to know whether they are satisfied. But since desiring something typically does involve caring at least somewhat about it, these considerations support the weaker claim that I am making: that first-order desires are usually accompanied by such second-order desires. This claim is not only plausible but widely accepted, at least implicitly: when people are asked to imagine that someone desires that p, they implicitly assume that this person also desires to know whether p obtains – unless, of course, they are told something that suggests otherwise. So, when people read about Parfit's example, they are likely to assume that Parfit wants to know whether his desire is satisfied.

It is possible, though unusual, to have a desire without also wanting to know whether that desire is satisfied.Footnote 9 If people assume that Parfit is indifferent about knowing whether his desire that the stranger be cured is satisfied, then my response says that they should think that Parfit benefits from the satisfaction of the remote desire, and that he benefits more than he would if he had a desire to know. This seems to me to be the right thing to say.

It would be even more unusual to have a desire while also wanting not to know whether that desire is satisfied. But if someone assumes that Parfit for some reason desires not to know whether the stranger is cured while desiring that the stranger be cured, then my response says that they should think that he benefits from the satisfaction of the remote desire, and that he benefits more than he would if he were to desire to know (and also more than he would if he were indifferent about knowing). This also seems to me to be the right thing to say.

According to this response, remote desires are relevant to well-being, but they seem irrelevant to well-being because they are typically accompanied by other desires that are frustrated. For those who are inclined to say that remote desires really are irrelevant to well-being, it might be helpful to compare two versions of Parfit's example. In the first version, Parfit meets a stranger, learns that the stranger is ill, and forms a desire that the stranger be cured. Parfit never sees the stranger again, and unbeknownst to him, the stranger is cured. Crucially, Parfit neither forms a desire to know nor a desire not to know whether the stranger is cured. The second version is the same as the first version in every way except that Parfit does not form the desire that the stranger be cured. I find it plausible that Parfit's life goes better, even if it is just a little bit, if he were to have the desire that the stranger be cured than if he were not to have that desire, given that the stranger is eventually cured. If you share this intuition, then you should think that remote desires are relevant to well-being.Footnote 10

My response bites the bullet, just as Lukas's does, but it is an improvement on his in one crucial respect: it can make sense of why, in a case where Parfit has many strong desires about strangers whom he never meets again, he still does not seem to benefit much when these desires are all satisfied. Lukas has to say that Parfit benefits a great deal in this case because his response relies solely on the strengths and quantity of remote desires relative to the strengths and quantity of non-remote desires: he does not identify any desires that are typically frustrated when remote desires are satisfied and whose frustration cancels out at least some of the value of the satisfaction of remote desires. My response identifies desires of precisely that sort: it says that whenever Parfit has a remote desire, it is likely that he also has a desire to know whether that remote desire is satisfied, and the disvalue of the frustration of this desire cancels out at least part of the value of the satisfaction of the remote desire. Thus, my response implies that Parfit benefits less than Lukas's response implies that he does in the case in which he has many satisfied remote desires about strangers. It therefore does a better job than Lukas's response does on its own of explaining why we might mistakenly think that Parfit does not benefit at all in that case. More generally, it does a better job of making it credible that when we judge that people do not benefit at all from the satisfaction of their remote desires, we are mistaking a situation in which they benefit only modestly for one in which they do not benefit at all. When combined with Lukas's observations about the rarity and relative weakness of remote desires, my response makes it more credible than those observations do on their own that remote desires are, despite appearances, relevant to well-being.Footnote 11

There is one way in which my response leaves something to be desired, however.Footnote 12 Even if remote desires are typically accompanied by desires to know whether they are satisfied, it is possible for a remote desire to be far stronger than its accompanying desire to know. Your desire that people living centuries from now flourish might, for example, be much stronger than your desire to know whether they will flourish – as evidenced by your willingness to expend far more time, effort, or money to satisfy the former desire than to satisfy the latter. My response implies that, in a case like this, one benefits a great deal on balance from the satisfaction of the remote desire, since only a small fraction of the value of its satisfaction is canceled out by the disvalue of the frustration of the accompanying desire to know. Perhaps many of those who have the intuition that people do not benefit at all from the satisfaction of remote desires could be persuaded that people benefit somewhat from their satisfaction. But presumably, far fewer of them could be persuaded that people sometimes benefit a great deal from their satisfaction. For this reason, I am not prepared to declare victory over the problem of remote desires on behalf of the desire-satisfaction theory. It nonetheless seems to me that my response to the problem is the best one developed so far that does not require a departure from the standard version of the desire-satisfaction theory.

One last objection deserves to be mentioned. I have been assuming that Parfit's desire to know whether the stranger is cured begins to be frustrated at the same time that the desire that the stranger be cured begins to be satisfied: when the stranger is cured. It is for this reason that Parfit appears to benefit less from the satisfaction of his first-order desire than he does: the value of the satisfaction of that desire (say, 5) arrives simultaneously with the disvalue of the frustration of the desire to know (say, –3), with the result that his welfare score increases by 2 instead of 5. But it might seem that the desire to know begins to be frustrated at the much earlier time at which Parfit acquires it, since he does not know, at that time, whether the stranger will be cured. If this is correct, then the frustration of the desire decreases Parfit's welfare long before the satisfaction of the desire for a cure increases it, and the value of the latter cannot be obscured by the disvalue of the former.Footnote 13

My response draws on McDaniel and Bradley's (Reference McDaniel and Bradley2008) astute observation that our desires are typically conditional desires (i.e., desires for p on the condition that q) and that a conditional desire can neither be satisfied nor frustrated, regardless of whether its object obtains, unless its condition is met. For example, my desire to watch a movie tonight is not a desire to watch a movie tonight no matter what: it is conditional on my still wanting to do this when the night comes. If I still want to watch a movie tonight but I don't, then since the condition of my desire is met and its object does not obtain, my desire is frustrated. But if I no longer want to watch a movie when the night comes, then since the condition of my desire is not met, my desire is not frustrated but canceled.

The claim that Parfit's desire to know begins to be frustrated immediately when he acquires it presupposes that this desire doesn't have a condition that isn't met at that time. For if the desire does have such a condition, then even though the desire's object does not obtain then, the desire is canceled (or not yet active) rather than frustrated at that time. I think that, on the most psychologically realistic way of imagining the example, the desire does have such a condition: that there be a fact of the matter about whether the stranger will be cured. Surely Parfit doesn't want to know whether the stranger will be cured regardless of whether there is a fact of the matter about this: for if he did, he would want to know the fact of the matter about something regardless of whether there even is a fact of the matter about it. Even if we grant that people can have desires of this sort, they are surely rare and limited to cases in which the agent cares far more fervently about the matter at hand than Parfit does about whether the stranger will be cured (e.g., a case in which a diehard football fan wants to know who his team's starting quarterback will be).Footnote 14 But if Parfit's desire to know is conditional on there being a fact of the matter about whether the stranger will be cured, then since there is no fact of the matter about this when he acquires that desire, the desire does not begin to be frustrated at that time. Instead, it begins to be frustrated when there is a fact of the matter about whether the stranger will be cured – viz., the time at which the stranger is cured, or some slightly earlier time. Thus, the desire frustration from the desire to know does coincide temporally (at least approximately) with the desire satisfaction from the first-order desire and can therefore obscure the gain from that desire satisfaction.

Suppose, however, that Parfit's desire to know is not conditional in the way that I have just described. My response to the problem of remote desires would still have some force. This is because the satisfaction of his desire that the stranger be cured would still differ in one important way from typical cases of desire satisfaction: whereas in typical cases, the desire to know is satisfied when the first-order desire is satisfied and we simultaneously accrue some welfare from both desires, Parfit gets no welfare from his desire to know while he accrues welfare from his first-order desire. His welfare score increases by 5 (from the first-order desire), whereas in a typical case, his score would increase by 8 (5 from the first-order desire, 3 from the desire to know). The fact that Parfit does not benefit as much as he would in a typical case of desire satisfaction might mislead us into thinking that he does not benefit at all.

5. Conclusion

In this article, I considered two objections to the desire-satisfaction theory of well-being – the objection from prudential neutrality and the objection from remote desires – and I developed a unified strategy for responding to both objections. The strategy is to argue that, in light of the existence of desires that are initially hidden from view, the desire theory can say, or come close to saying, what these objections fault it for being unable to say. In cases of prudential neutrality, the agent prudentially ought not to be neutral between the two options because there are hidden desires that are satisfied in one option but frustrated in the other. In cases of remote desires, the agent merely appears not to benefit from the satisfaction of the remote desire because there is a frustrated hidden desire (viz., the desire to know whether the remote desire is satisfied) that confounds people's intuitions about whether the agent benefits from the satisfaction of the remote desire. I also rejected other responses to the objections, either on the grounds that they have counterintuitive implications or on the grounds that they abandon the standard desire-satisfaction theory to which the objections are directed. If my strategy is successful, then the desire-satisfaction theory is more promising than many have taken it to be.Footnote 15