Introduction

Glufosinate-ammonium is a broad-spectrum, nonselective herbicide labeled to control dicotyledons and certain monocotyledons. In the United States, this herbicide was first registered in 1993 by AgrEvo under the commercial names Finale® and Rely® (Bijman Reference Bijman2001; Hoerlein Reference Hoerlein1994). Glufosinate is one of the foundational postemergence herbicides in LibertyLink® (BASF, Florham Park, NJ, USA), Enlist™ (Corteva Agriscience, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and XtendFlex® (Bayer CropScience, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) systems, in which crops contain the glufosinate-resistance trait. Glufosinate controls plants by inhibiting the glutamine synthetase enzyme, which synthesizes glutamine from glutamate with photorespiratory ammonia. Because the herbicide is a chemical analogue to glutamate, it competes with this amino acid to bind to the enzyme. Inhibition of glutamine synthetase eventually leads to ammonia accumulation, amino acid depletion, detrimental accumulation of reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, and, ultimately, cell death (Bayer et al. Reference Bayer, Gugel, Hägele, Hagenmaier, Jessipow, König and Zähner1972; Takano et al. Reference Takano, Beffa, Preston, Westra and Dayan2019, Reference Takano, Beffa, Preston, Westra and Dayan2020; Wendler et al. Reference Wendler, Barniske and Wild1990; Wild and Manderscheid Reference Wild and Manderscheid1984). In plants, glutamine synthetase has two major isoforms in different compartments: one located in the cytosol (GS1) and the other located in the chloroplasts (GS2) (Mann et al. Reference Mann, Fentem and Stewart1979). GS1 is associated to nitrogen assimilation that will generate glutamine for nitrogen transport inside plants, while GS2 is involved in the reassimilation of ammonium from the photorespiratory pathway and other plant processes (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Walker and Coruzzi1990; Kamachi et al. Reference Kamachi, Yamaya, Mae and Ojima1991; Wallsgrove et al. Reference Wallsgrove, Turner, Hall, Kendall and Bright1987).

Compared with other frequently used nonselective herbicides such as glyphosate and paraquat, glufosinate has a relatively lower number of resistant weed species. Currently, only five weed species have been confirmed resistant to glufosinate. These weeds are goosegrass [Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn.], Italian ryegrass [Lolium perenne L. ssp. multiflorum (Lam.) Husnot], perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.), rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaudin), and Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri S. Watson). Amaranthus palmeri is the first and only broadleaf weed resistant to glufosinate (Avila-Garcia and Mallory-Smith Reference Avila-Garcia and Mallory-Smith2011; Ghanizadeh et al. Reference Ghanizadeh, Harrington and James2015; Heap Reference Heap2022b; Jalaludin et al. Reference Jalaludin, Ngim, Bakar and Alias2010; Priess et al. Reference Priess, Norsworthy, Godara, Mauromoustakos, Butts, Roberts and Barber2022; Seng et al. Reference Seng, Lun, San and Sahid2010; Travlos et al. Reference Travlos, Cheimona, De Prado, Jhala, Chachalis and Tani2018).

According to the Herbicide Resistance Action Committee, confirmation of herbicide resistance starts with the seed collection from weeds surviving the lethal dose of a specific product, followed by herbicide screening and a dose–response experiment with whole plants in a greenhouse (Heap Reference Heap2005). In 2019 and 2020, Arkansas farmers from Crittenden and Mississippi counties noticed that glufosinate applications failed to control A. palmeri plants. Seeds from these fields were collected, and glufosinate resistance was confirmed through dose–response experiments (Priess et al. Reference Priess, Norsworthy, Godara, Mauromoustakos, Butts, Roberts and Barber2022). In addition to glufosinate, A. palmeri is resistant to herbicides targeting eight other sites of action, which makes this weed extremely challenging to control (Heap Reference Heap2022b). Although the resistance has been confirmed, the resistance mechanism in glufosinate-resistant A. palmeri remains unrevealed.

The possible mechanisms of resistance are divided into target-site and non–target site mechanisms. Target-site resistance encompasses any alteration in the target enzyme that will prevent herbicide binding, such as amino acid/nucleotide change. Gene amplification and overexpression of the targeted protein are also considered to be target-site resistance mechanisms. Non–target site resistance is any plant mechanism that reduces the quantity of herbicide reaching the target site (Délye et al. Reference Délye, Jasieniuk and Le Corre2013; Powles and Yu Reference Powles and Yu2010). It is crucial to understand the basis of herbicide resistance and the biology of a weed population. With this knowledge, scientists can design and apply proper strategies to limit the spread of resistance (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Ward, Shaw, Llewellyn, Nichols, Webster, Bradley, Frisvold, Powles, Burgos, Witt and Barrett2012). Glufosinate resistance was characterized in three A. palmeri accessions from Arkansas by Priess et al. (Reference Priess, Norsworthy, Godara, Mauromoustakos, Butts, Roberts and Barber2022), and a high resistance level was observed in one of these accessions (resistance/susceptibility ratio = 24). In this study, this highly glufosinate-resistant accession was further used to investigate the mechanism conferring resistance to glufosinate.

Materials and Methods

One A. palmeri accession previously confirmed to have high glufosinate resistance (resistance/susceptibility ratio = 24) was selected to conduct the experiments described. The seeds from the resistant accession (Glu-R1) were collected in 2020 from a cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) field where glufosinate applications failed to provide control (Priess et al. Reference Priess, Norsworthy, Godara, Mauromoustakos, Butts, Roberts and Barber2022). Additionally, two susceptible A. palmeri accessions collected in South Carolina in 1986 (S1) and in Arkansas in 2001 (S2) were used for comparison. Seedlings were established in a greenhouse at 25 ± 5 C and 16-h day at the Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, AR, USA.

Glutamine Synthetase Sequencing

Illumina sequencing was conducted on RNA from Glu-R1 survivors and S1 nontreated plants to identify the presence of GS1 and GS2 mutations possibly correlated with target-site resistance. Approximately 1 g of leaf tissue was collected from glufosinate-resistant and glufosinate-susceptible A. palmeri accessions, frozen using liquid nitrogen, and then ground to fine powder. The finely powdered leaf tissue of each accession was processed using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to extract RNA. The quality and quantity of RNA were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA samples were immediately stored at −80 C until further processing for transcriptomic sequencing. RNA samples of the Glu-R1 and S1 accessions of A. palmeri were analyzed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 instrument (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) to determine the RNA integrity number. Prepared libraries were run on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instrument (Novogene, Beijing, China) to produce 150-bp paired-end reads. The sequence read data were evaluated to determine the percentage of reads containing adapters, reads containing N >10% (N represents the base that cannot be determined), and reads of low quality (Qscore ≤ 5) before releasing the data.

Paired-end reads were assembled using Trinity (https://github.com/trinityrnaseq), with standard flags of Trimmomatic (Bolger et al. Reference Bolger, Lohse and Usadel2014). Assembled contigs were annotated using Trinotate (https://trinotate.github.io), and peptide sequences were produced using TransDecoder (http://transdecoder.github.io). Glutamine synthetase nucleotide and peptide sequences were extracted from fasta files using the TrinotateExtractor (http://github.com/mcelrjo/trinotateExtractor) based on Blast annotation in the Trinotate output file. Protein sequences were aligned within each accession to eliminate redundant sequences and were sorted within each accession to refine annotation to specific glutamine synthetase orthologues based on Blast annotation. The Glu-R1 and S1 protein sequences derived from TransDecoder were aligned for GS1 and GS2 to identify any amino acid differences. Protein sequences were aligned to reference protein sequences of glutamine synthetase cytosolic and chloroplastic isozymes from A. palmeri (NCBI accession GFQG01042326.1 and Heap [Reference Heap2022a], respectively). The GS1 and GS2 isozymes of cantaloupe (Cucumis melo L.) (NCBI accessions NP_001284433.1 and NP_001284439.1, respectively) were included as an unrelated species to demonstrate the sequence homology across diverse taxa. Illumina sequencing reads for Glu-R1 and S1 were submitted as NCBI BioProject PRJNA831848.

Read mapping was performed to identify numerical differences in expression between Glu-R1 and S1 accessions. Illumina sequencing of the Glu-R1 biotype generated 22,582,008 paired-end reads, while sequencing of the S1 biotype generated 10,883,584 paired-end reads. Reads were mapped using the CLC Genomics Workbench (CLCbio, Seoul, Republic of Korea) read mapping tool with the following settings: no masking, match score 1, mismatch cost 2, linear gap cost for insertions and deletions, insertion cost 3, deletion cost 3, length fraction of 0.5, similarity fraction of 0.8, and no global alignment. Read counts, average coverage of reads, and the percent of the total reads mapped are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Glutamine Synthetase Gene Copy Number Quantification

Gene copy number assay was conducted with nontreated plants from the susceptible accessions (S1 and S2), and glufosinate survivors from the resistant accession (Glu-R1) sprayed with glufosinate (Interline®, UPL Limited, King of Prussia, PA, USA) at 656 g ai ha−1 at the 5- to 7-leaf stage. Around 100 mg of leaf tissue was collected per plant from four plants of each accession, and genomic DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A.® Plant DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. After extraction, DNA was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and diluted with deionized water to 10 ng µl−1. A quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was conducted to quantify the cytoplasmatic (GS1) and chloroplastic (GS2) glutamine synthetase copy number. The primers GS1a and GS2a were designed to quantify gene copy number for GS1 or GS2, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Primer pairs used to quantify relative copy number and gene expression by real-time polymerase chain reaction in Amaranthus palmeri accessions.

a Gs1a (cytoplasmatic) and Gs2a (chloroplastic) glutamine synthetase in gene copy number experiment; Gs1b (cytoplasmatic) and Gs2b (chloroplastic) glutamine synthetase in gene expression experiment; CCR, Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase; PPAN, peter Pan-like.

b F, forward; R, reverse.

c Primer information is presented in Takano and Dayan (Reference Takano and Dayan2021) and González-Torralva and Norsworthy (Reference González-Torralva and Norsworthy2021).

The qPCR reaction mixture (20 µl) consisted of 10 µl of 2× SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), 0.8 µl each of 10 µM forward and reverse primers (Table 1), 5.9 µl of deionized water, and 25 ng of genomic DNA. The assay was conducted in a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) under the following conditions: 98 C for 3 min, 40 cycles of 98 C for 10 s, and 61 C for 30 s. Melting curves were created by increasing the temperature from 65 C to 95 C, 0.5 C every 5 s to ensure specific amplification. Each biological sample (total of four per accession) had two technical replicates in each primer pair, and the experiment was repeated in time. No-template controls (DNA substituted by deionized water) were included in each plate. Quantification cycles (Cq) were produced by CFX Maestro software (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and genomic copy numbers of GS1 and GS2 were calculated using a modified version of the 2−ΔΔCt method (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons and Jiang2010; Livak and Schmittgen Reference Livak and Schmittgen2001). Fold increase in GS1 and GS2 was assessed relative to two reference genes (single gene copy) previously used in A. palmeri, Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), and Peter Pan-like (PPAN) (González-Torralva and Norsworthy Reference González-Torralva and Norsworthy2021; Salas et al. Reference Salas, Dayan, Pan, Watson, Dickson, Scott and Burgos2012).

Glutamine Synthetase Gene Expression

The gene expression assay was conducted with nontreated plants from the same susceptible and glufosinate-resistant accessions described earlier. Approximately 100 mg of leaf tissue was collected per plant from three plants of each accession and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted using the Monarch Total RNA Miniprep Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After extraction and quantification in a spectrophotometer, a total of 1 µg RNA per sample was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). This cDNA was used to quantify the cytoplasmatic (GS1) and chloroplastic (GS2) glutamine synthetase expression using primer pairs GS1b and GS2b, respectively (Table 1).

The qPCR reaction mixture followed the same methodology described in “Glutamine Synthetase Gene Copy Number Quantification” with forward and reverse primers described in Table 1. The primer pairs GS1b and GS2b amplifying GS1 and GS2, respectively, were obtained from a previous study targeting these genes in A. palmeri (Takano and Dayan Reference Takano and Dayan2021). The assay was conducted under the following conditions: 30 s at 98 C, 40 cycles of 98 C for 10 s, and 60 C for 30 s. After the cycle was completed, the temperature increased by 0.5 C every 5 s from 65 C to 95 C to generate melting curves. Two technical replicates were used for each biological sample (total of three per accession), and the experiment was repeated in time. No-template controls were included on each plate. Quantification cycles (Cq) were produced by CFX Maestro software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The Ct values of GS1 and GS2 in resistant and susceptible plants were normalized against the reference genes CCR and PPAN (Table 1), and relative expression was calculated against susceptible accessions using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen Reference Livak and Schmittgen2001).

Absorption and Translocation of Glufosinate

Absorption and translocation experiments of 14C-labeled glufosinate were conducted in resistant (Glu-R1) and susceptible (S1 and S2) accessions. Amaranthus palmeri seedlings were transplanted into 7-cm-diameter plastic pots filled with potting mix (Sun Gro® Horticulture, Agawam, MA, USA). Each accession had three replications that consisted of one plant per pot in each replication. The experiment was organized in a completely randomized design and repeated twice. At the 6- to 8-leaf stage, plants received an overspray of nonradioactive glufosinate at 656 g ai ha−1. The overspray was applied using a spray chamber equipped with 1100067 nozzles (TeeJet® Technologies, Springfield, IL, USA) calibrated to deliver 187 L ha−1 at 1.6 km h−1. Immediately after nonradioactive herbicide application, plants were spotted with [14C]glufosinate. A working solution of [14C]glufosinate was prepared in the overspray solution. Four 0.5-µl droplets, each containing 1 kBq of [14C]glufosinate, were placed on the second fully expanded leaf of each treated plant. Therefore, a total of 4 kBq of radiolabeled herbicide was spotted per plant. The treated plants were maintained in a greenhouse set to 25 C under a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod. There was no function inside the greenhouse to regulate the relative humidity, and this factor was relatively low (≤50%) throughout both runs. Nontreated plants were maintained as a control.

At 48 h after 14C-labeled herbicide treatment, plants were collected and divided into four sections: treated leaf (TL), above treated leaf (ATL), below treated leaf (BTL), and roots. Roots were washed to remove soil residues. The treated leaf was collected from each plant and rinsed with 5 ml of methanol. The rinsate was gathered in a 20-ml scintillation vial containing 10 ml of scintillation cocktail (Ultima Gold™, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and analyzed with a Tri-Carb 2900TR Liquid Scintillation Analyzer (LSA; PerkinElmer). Absorption was calculated by subtracting the [14C]glufosinate activity in the rinsate of the treated leaf at the sampling time from the [14C]glufosinate activity in the rinsate of the treated leaf at the initial time. The initial [14C]glufosinate recovery was 95%, and it was obtained by washing treated leaves soon after spotting treatment.

Each plant section was individually placed into a paper envelope and then dried in a freeze-dryer (Botanique Preservation Equipment, Phoenix, AZ, USA) at −50 C for 72 h. The dried plant parts were individually combusted to 14CO2 by a biological oxidizer (Model OX-700, R.J. Harvey Instruments, Tappan, NY, USA) at 900 C for 3 min. The 14CO2 gas was entrapped into 15 ml of 14C-trapping cocktail (R.J. Harvey Instrument). The 14C activity in the vials was analyzed using the LSA. Translocation was calculated as the proportion of the [14C]glufosinate measured in each plant part relative to the total [14C]glufosinate absorbed after 48 h.

Metabolism of Glufosinate

Metabolism experiments were conducted twice on the same dates on which the absorption/translocation experiment were being performed. Amaranthus palmeri plant sample preparation, non-radiolabeled herbicide spray, and 14C-labeled herbicide treatment were done following the same methods as used in the absorption/translocation experiment. At 48 h after 14C-labeled herbicide treatment, the treated leaf was thoroughly rinsed with 15 to 20 ml of methanol to eliminate the 14C-labeled herbicide persisting on the leaf surface. Following the leaf wash, each plant was placed into a paper envelope without dissection and then freeze-dried for 72 h.

Extraction of [14C]glufosinate and its metabolites from metabolism samples was performed based on the analytical method proposed by Küpper et al. (Reference Küpper, Peter, Zöllner, Lorentz, Tranel, Beffa and Gaines2018) and Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Peter, Norsworthy and Beffa2020). The dried plant sample was cut into small pieces (<2 mm) and then transferred into a 2-ml Eppendorf tube containing 600 µl of 90% methanol in water. Subsequently, the sample was thoroughly ground using a polypropylene pellet pestle. After 30 s of vortexing, the sample was left at 4 C in a refrigerator for 1 h and then centrifuged at 8000× g for 6 min. The supernatant was transferred to an evaporating flask. The residue remaining in the tube was additionally extracted with 600 µl of 90% acetonitrile in water, followed by 600 µl of 10% methanol in water. All supernatants of additional extracts were combined on the same evaporating flask with the initial supernatant and then evaporated to <1 ml using an Xcelvap evaporator (Horizon Technologies, Lake Forest, CA, USA). The evaporated sample was reconstituted to 1 ml with methanol and filtered using a 0.2-µl polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) syringe filter. The quantification of [14C]glufosinate in the samples was conducted using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Prominence-i LC-2030C 3D, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) linked to a LabLogic Beta-Ram Model 4B radiation detector (RAD; LabLogic Systems, Tampa, FL, USA).

A 25-µl aliquot from the final sample solution was injected into the HPLC–RAD system. The mobile phases consisted of 50 mM ammonium acetate in water (A) and HPLC reagent grade water (B). Solvents were run for a 1-min plateau at 15% solvent A, a 5-min linear gradient from 15% to 30% of solvent A plateauing for 2 min, followed by a linear gradient returning to 15% solvent A in 5 min. The column was then flushed with 15% solvent A for 2 min. A SeQuant ZIC-pHILIC 5 µM polymeric LC column (100 cm in length by 4.6 mm in inner diameter, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to separate [14C]glufosinate from the sample matrices. The column oven temperature was kept at 40 C, and the flow rate of mobile phases was 0.5 ml min−1. The recovery in the blank A. palmeri sample treated with 1.0 kBq of [14C]glufosinate was >85%. Metabolism (%) was calculated by subtracting the 14C activity of the parent compound from the 14C activity absorbed at 48 h after [14C]glufosinate treatment.

Data Analysis

All data collected were subjected to ANOVA in JMP Pro v. 15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The experimental runs were not significant across the experiments and were thus set as a random effect in the subsequent statistical model statement. If significant, means from gene copy number and gene expression assays were separated using Fisher’s protected LSD at α = 0.05. Results of absorption, translocation, and metabolism were also subjected to ANOVA and separated using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) at α = 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Glutamine Synthetase Sequencing, Relative Copy Number, and Expression

Protein isoforms were compared to identify any amino acid substitutions present in the resistant (Glu-R1) in comparison to the susceptible (S1) A. palmeri accession and reference sequences (A. palmeri and C. melo). Based on amino acid sequences, one isoform of cytosolic resistant (Glu-R1) and susceptible (S1) was identified and aligned with the reference cytosolic GS (Supplementary Figure 1). The sequences did not assemble correctly past Trp-306 due to poor alignment quality past this point of the sequencing. While differences between the C. melo reference and Glu-R1 and S1 were observed, no differences were observed between the A. palmeri accessions (reference, Glu-R1, and S1). For chloroplastic GS, only one isoform was identified (Supplementary Figure 2). The Glu-R1 GS2 isoform (GSChl_Glu-R1) contained one amino acid substitution (Gly-20-Ser) not present in GS2 from S1 or the A. palmeri reference. However, Blastp alignment inspection of this region identified that this position shows high amino acid polymorphism across different species. Due to this lack of evolutionary conservation, it is unlikely that this substitution would constitute a target-site resistance, but additional studies such as cloning vectors need to be conducted to prove this hypothesis. Little numerical difference was observed in GS1 between Glu-R1 and S1 reads (Supplementary Table 1). For GS1, 0.013% to 0.035% of total reads mapped to either accession with no obvious numerical differences. For GS2, greater numerical difference was observed between the biotype reads. Glu-R1 reads mapped to 0.079% to 0.242% of the total reads, while S1 reads only mapped to 0.018% of total reads. The mapping difference translates to 4.4 to 13.4 times greater expression for Glu-R1 than S1.

Figure 1. Cytoplasmatic glutamine synthetase copy number (A) and expression (B) relative to Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) and peter Pan-like (PPAN) reference genes in glufosinate-resistant (Glu-R1) and glufosinate-susceptible (S1 and S2) accessions. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n = 8 and n = 6). Means were subjected to ANOVA, and P-values were generated using JMP Pro v. 15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Figure 2. Chloroplastic glutamine synthetase copy number (A) and expression (B) relative to Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) and peter Pan-like (PPAN) reference genes in glufosinate-resistant (Glu-R1) and glufosinate-susceptible (S1 and S2) accessions. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n = 8 and n = 6). Means were subjected to ANOVA, and P-values were generated using JMP Pro v. 15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Means displayed with different uppercase letters are different according to Fisher’s protected LSD test at α = 0.05.

Sequence data for both GS1 and GS2 suggest that a point mutation does not contribute to glufosinate resistance in the Glu-R1 accession. Working with a glufosinate-resistant L. perenne accession, Avila-Garcia et al. (Reference Avila-Garcia, Sanchez-Olguin, Hulting and Mallory-Smith2012) identified an amino acid substitution of aspartate for asparagine in the GS2 gene, which was initially considered the resistance mechanism. However, further investigation led to the conclusion that this alteration in GS2 could not account for glufosinate resistance in this specific accession (Brunharo et al. Reference Brunharo, Takano, Mallory-Smith, Dayan and Hanson2019). In a recent investigation conducted with glufosinate-resistant E. indica, Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Yu, Han, Yu, Nyporko, Tian, Beckie and Powles2022) identified the substitution of a serine for glycine at the 59th position of GS1 in the resistant accession, which is likely the resistance mechanism in this accession. This substitution was also encountered in glufosinate-resistant E. indica from different regions and countries. Mutation in the target enzyme might confer glufosinate resistance in the other A. palmeri accessions not tested in this study.

Gene copy number and gene expression assays were conducted to detect any differences in the cytoplasmatic and chloroplastic glutamine synthetase (GS1 and GS2, respectively) among the A. palmeri biotypes. Regarding the GS1 copy number relative to the reference primers, there was no difference between susceptible and resistant plants, and all accessions had approximately one GS1 copy (Figure 1A). Similarly, GS1 expression was not different within the accessions (Figure 1B). Based on these results, glufosinate resistance in A. palmeri did not involve gene amplification or increased expression of cytosolic glutamine synthetase. The cytosolic isoform of the GS enzyme is essential in the assimilation and transport of nitrogen throughout the plant. GS1 and GS2 enzyme activities greatly vary among species, plant sections, and plant stages (Bernard and Habash Reference Bernard and Habash2009; Brugiere et al. Reference Brugiere, Dubois, Masclaux, Sangwan and Hirel2000; Habash et al. Reference Habash, Massiah, Rong, Wallsgrove and Leigh2001; McNally et al. Reference McNally, Hirel, Gadal, Mann and Stewart1983; Miflin and Habash Reference Miflin and Habash2002; Woo et al. Reference Woo, Morot-Gaudry, Summons and Osmond1982). After applications of glufosinate to A. palmeri seedlings from Colorado, higher GS1 expression in old leaf or root tissues compared with young leaf tissues was found. Glufosinate has no soil activity and is recommended to be applied when A. palmeri plants are small and young; therefore, gene amplification or overexpression of GS1 might not impact resistance due to low GS1 expression in this plant stage.

GS2 copy number and expression were different within the glufosinate-resistant and glufosinate-susceptible accessions. Calculated against CCR and PPAN reference genes, accession Glu-R1 had 85 and 86 copies, respectively, while the two susceptible accessions had 2 GS2 copies (Figure 2A). For gene expression, accession Glu-R1 showed 15 and 31 times relative GS2 expression increase relative to CCR and PPAN, respectively (Figure 2B). The susceptible accessions showed no increase in GS2 expression. In a dose–response experiment, accession Glu-R1 showed 24-fold glufosinate resistance (Priess et al. Reference Priess, Norsworthy, Godara, Mauromoustakos, Butts, Roberts and Barber2022). The resistance fold obtained by Priess et al. (Reference Priess, Norsworthy, Godara, Mauromoustakos, Butts, Roberts and Barber2022) and the relative GS2 expression obtained in this study for accession Glu-R1 are similar, suggesting that high copy number and expression may confer high resistance. Therefore, gene amplification and overexpression of GS2 enzyme is likely the mechanism conferring glufosinate resistance in the A. palmeri accessions investigated in this study. Further experiments, such as examinations of enzyme activity and inheritance of this trait, remain to be conducted. This is the first report of increase in GS2 copy number or expression in a glufosinate-resistant species.

Herbicide resistance by gene amplification and overexpression has been previously reported in A. palmeri. Resistance to glyphosate can be due to an increased copy number of the target enzyme, 5-enolypyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS; Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons and Jiang2010; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Singh, Lawton-Rauh, Bagavathiannan and Roma-Burgos2018). Working with glyphosate-resistant A. palmeri accessions, Ribeiro et al. (Reference Ribeiro, Pan, Duke, Nandula, Baldwin, Shaw and Dayan2014) found that EPSPS relative copy number had a positive correlation with EPSPS expression, results similar to those obtained in the present study. It is important to note that Glu-R1 also exhibits resistance to glyphosate (Priess et al. Reference Priess, Norsworthy, Godara, Mauromoustakos, Butts, Roberts and Barber2022). Likewise, increased EPSPS relative copy number was observed in this accession (data not shown). Other glyphosate-resistant weeds, such as kochia [Bassia scoparia (L.) A.J. Scott.] and E. indica, also exhibit gene amplification as the resistance mechanism (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Huang, Zhang, Wei, Huang, Chen and Wang2015; Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Barker, Patterson, Westra and Wilson2016; Godar et al. Reference Godar, Stahlman, Jugulam and Dille2015). Gene amplification has also been observed in large crabgrass [Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) Scop.] resistant to acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitors (Laforest et al. Reference Laforest, Soufiane, Simard, Obeid, Page and Nurse2017). Although seldom identified as a herbicide-resistance mechanism, increase in gene copy number has been reported in several cases of fungicide or insecticide resistance (Anthony et al. Reference Anthony, Unruh and Ganser1998; Cattel et al. Reference Cattel, Haberkorn, Laporte, Gaude, Cumer, Renaud, Sutherland, Hertz, Bonneville, Arnaud, Fustec, Boyer, Marcombe and David2021; Elmore et al. Reference Elmore, McGary, Wisecaver, Slot, Geiser, Sink, O’Donnell and Rokas2015; Heckel Reference Heckel2022; Puinean et al. Reference Puinean, Foster, Oliphant, Denholm, Field, Millar, Williamson and Bass2010).

Interestingly, the gene amplification data strongly suggest that the GS2 gene in A. palmeri has two copies natively in susceptible plants (Figure 2A). A future experiment involving other A. palmeri accessions from different regions might further investigate this finding. GS2 duplication has been observed before in black cottonwood [Populus balsamifera L. ssp. trichocarpa (Torr. & A. Gray ex Hook.) Brayshaw], barrelclover (Medicago truncatula Gaertn.), and some green algae species (Castro-Rodríguez et al. Reference Castro-Rodríguez, García-Gutiérrez, Canales, Avila, Kirby and Cánovas2011; Ghoshroy et al. Reference Ghoshroy, Binder, Tartar and Robertson2010; Seabra et al. Reference Seabra, Vieira, Cullimore and Carvalho2010).

[14C]Glufosinate Absorption, Translocation, and Metabolism

No difference in glufosinate absorption was observed among resistant and susceptible accessions (Figure 3). Absorption ranged from 54% to 60% in the accessions, similar to the magnitude (59% to 85%) reported in previous studies with A. palmeri (Everman et al. Reference Everman, Thomas, Burton, York and Wilcut2009b; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Peter, Norsworthy and Beffa2020).

Figure 3. Absorption of [14C]glufosinate by glufosinate-resistant (Glu-R1) and glufosinate-susceptible (S1 and S2) accessions assessed at 48 h after application of radiolabeled herbicide. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n = 6). Means were subjected to ANOVA, and P-values were generated using JMP Pro v. 15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

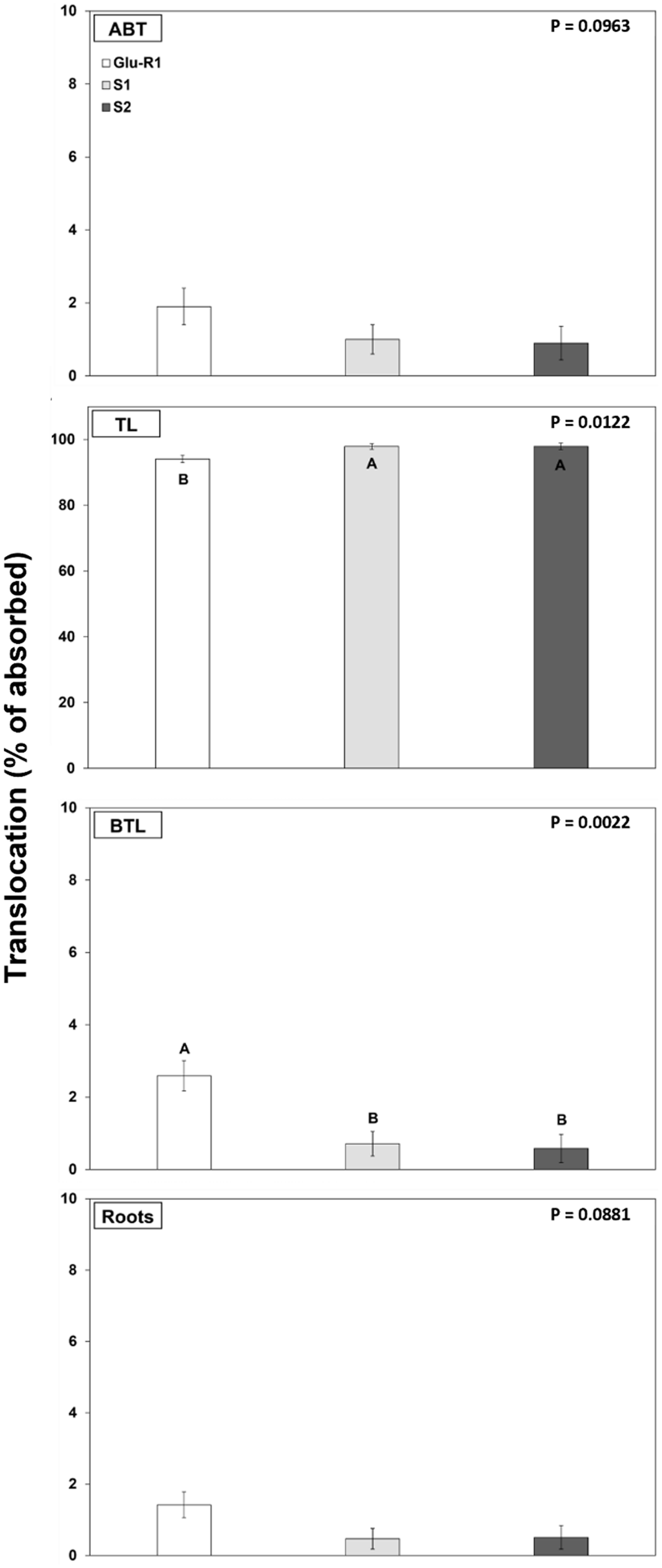

Most of the [14C]glufosinate absorbed remained in the treated leaf: 94% for Glu-R1 and 98% for susceptible accessions (P < 0.05) (Figure 4). Translocation of [14C]glufosinate to tissues above the treated leaf (1% to 1.9%) and roots (<1% to 1.4%) showed no difference among accessions. However, glufosinate translocation to tissues below the treated leaf (not including roots) was slightly greater in the Glu-R1 accession (2%) than in the susceptible accessions (<1%). Although the herbicide translocation to tissues below the treated leaf was statistically significant among the accessions, this negligible difference (1%) seems to be insufficient to explain the mechanism of glufosinate resistance. The low translocation (<6%) of [14C]glufosinate observed in this study was likely due to the localized phytotoxicity and rapid tissue necrosis caused by glufosinate, which possibly restrain translocation to other plants parts (Beriault et al. Reference Beriault, Horsman and Devine1999; Steckel et al. Reference Steckel, Hart and Wax1997). Low glufosinate translocation has been previously observed in A. palmeri and other weed species such as pitted morningglory (Ipomoea lacunosa L.) (Everman et al. Reference Everman, Mayhew, Burton, York and Wilcut2009a, Reference Everman, Thomas, Burton, York and Wilcut2009b; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Peter, Norsworthy and Beffa2020; Steckel et al. Reference Steckel, Hart and Wax1997).

Figure 4. Translocation of [14C]glufosinate by glufosinate-resistant (Glu-R1) and susceptible (S1 and S2) accessions assessed at 48 h after application by plant section. ABT, above-treated leaf; TL, treated leaf; BTL, below treated leaf. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n = 6). Means were subjected to ANOVA, and P-values were generated using JMP Pro v. 15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Means displayed with different uppercase letters are different according to Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test at α = 0.05.

Metabolism did not differ between the glufosinate-resistant and glufosinate-susceptible accessions, and the accessions metabolized 13% to 21% of the absorbed glufosinate at 48 h after treatment (Figure 5; Supplementary Figure 3). Previous studies reported total glufosinate metabolites in A. palmeri ranging from 31% to 62% of the total 14C absorbed (Everman et al. Reference Everman, Thomas, Burton, York and Wilcut2009b; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Peter, Norsworthy and Beffa2020). Metabolism varied from 20% to 30% in the broadleaf weeds common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album L.) and sicklepod [Senna obtusifolia (L.) Irwin & Barneby], respectively (Everman et al. Reference Everman, Mayhew, Burton, York and Wilcut2009a; Pline et al. Reference Pline, Wu and Hatzios1999). Metabolism results observed in this study demonstrate that a mechanism enhancing herbicide metabolism was not involved in evolution of glufosinate resistance in the tested A. palmeri.

Figure 5. Metabolism of [14C]glufosinate by glufosinate-resistant (Glu-R1) and glufosinate-susceptible (S1 and S2) accessions assessed at 48 h after application. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n = 6). Means were subjected to ANOVA, and P-values were generated using JMP Pro v. 15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

The overall results of uptake, translocation, and metabolism show that the resistance evolution to glufosinate in A. palmeri is not attributable to the non–target site resistance mechanisms investigated in this study. A similar result was reported in glufosinate-resistant E. indica, in which the resistant accession had no changes in uptake, translocation, or enhanced metabolism (Jalaludin et al. Reference Jalaludin, Yu, Zoellner, Beffa and Powles2017). In contrast, one glufosinate-resistant L. perenne population from Oregon showed increased metabolism compared with the susceptible standard (Brunharo et al. Reference Brunharo, Takano, Mallory-Smith, Dayan and Hanson2019). Another non–target site resistance mechanism is herbicide degradation by glutathione conjugation (Powles and Yu Reference Powles and Yu2010). However, in a previous study conducted with the addition of 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (NBD-Cl), a glutathione S-transferase inhibitor, to glufosinate, there was no difference in mortality when resistant A. palmeri was treated with only glufosinate or glufosinate plus NBD-Cl (Carvalho-Moore et al. Reference Carvalho-Moore, Norsworthy, Gonzalez-Torralva, Barber and Piveta2021). Other investigations into areas such as the influence of the addition of cytochrome P450 inhibitors or reactive oxygen species accumulation in different biotypes remain to be conducted.

In conclusion, the results obtained strongly indicate that glufosinate resistance in the investigated A. palmeri accession from Arkansas is likely a result of increased chloroplastic glutamine synthetase copy number and overexpression. No alterations were observed in the cytosolic glutamine synthetase isoform. There was no change observed in absorption, translocation, or metabolism; therefore, it can be concluded that these three non–target site resistance mechanisms do not influence the glufosinate resistance level in the resistant accession assessed in this study. Future efforts will focus on the heritability of this mechanism across generations, correlation between gene expression and enzyme activity, and alternative control methods targeting this problematic accession. Along with resistance mechanism investigations, glufosinate screenings with A. palmeri field accessions that have survived one or more applications of glufosinate have been conducted yearly for the past 4 yr at the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture. These screenings aim to identify other potentially glufosinate-resistant accessions and provide farmers rapid identification of problematic areas, consequently minimizing the dissemination of a resistant accession to neighboring fields.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2022.31

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the Arkansas Soybean Promotion Board and BASF Corporation. No conflicts of interest have been declared.