Introduction

In 2023, the United States produced approximately 389.67 billion kg of grain corn, accounting for more than 30% of the world’s total corn production, and >88% of the total U.S. corn was produced in the Midwest region (USDA-NASS 2024). Wisconsin is one of the main contributors to the overall corn production in the Midwest, with more than 1.2 million ha planted for grain and 356,000 ha for silage production in 2023 (USDA-NASS 2023). Weed management is a major challenge in corn production systems, whereas poor weed management may result in up to 69% yield loss (Ford et al. Reference Ford, Soltani, Robinson, Nurse, McFadden and Sikkema2014; Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Dille, Burke, Everman, VanGessel, Davis and Sikkema2016).

In U.S. midwestern corn production, herbicides and tillage represent the predominant weed management strategies (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Mitchell, Davis and Recker2017). Most corn growers design their chemical weed strategies by spraying herbicides as one-pass preemergence, one-pass postemergence, preemergence followed by (fb) postemergence (two-pass), or multiple postemergence applications (Lindsey et al. Reference Lindsey, Everman, Chomas and Kells2012; Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Vyn and Sikkema2009). However, selecting an economically effective herbicide strategy based on environmental conditions and weed composition can be challenging for conventional tillage corn growers (Mobli et al. Reference Mobli, DeWerff, Arneson and Werle2023). The 2018 Wisconsin cropping systems weed management survey documented that 62% of Wisconsin corn growers implement conventional tillage and a one-pass herbicide application (Werle and Oliveira Reference Werle and Oliveira2018). In certain situations, a timely one-pass application may effectively control weeds and save significant time and cost; however, it can result in inconsistent weed control and crop yield loss (Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Nurse, Gillard and Sikkema2013). Precipitation and adequate soil moisture play a crucial role in the incorporation and activity of residual herbicides in soil solution, which can be sprayed either preemergence or postemergence, or both, onto corn (Ross and Lembi Reference Ross and Lembi1985). Hence, dry spring and early summer conditions may reduce soil residual herbicide weed control efficacy. Moreover, some preemergence-only programs may not effectively control large-seeded broadleaf and perennial weeds and late-emerging small-seeded weeds (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Hager, Tranel, Davis, Martin and Williams2021; Mobli et al. Reference Mobli, DeWerff, Arneson and Werle2023; Severo Silva et al. Reference Severo Silva, Arneson, DeWerff, Smith, Silva and Werle2023; Trolove et al. Reference Trolove, Rahman, Hagerty and James2011). Therefore, the proper selection of an effective herbicide strategy plays a critical role in the success of weed management.

Including a postemergence herbicide into one’s weed management strategy provides the opportunity for growers to monitor the weed spectrum and adjust application time and herbicide program accordingly. Nevertheless, yield loss due to early season weed interference may occur before the postemergence application under high weed pressure. The presence of herbicide-resistant biotypes may result in poor postemergence control (Page et al. Reference Page, Cerrudo, Westra, Loux, Smith, Foresman, Wright and Swanton2012; Werle et al. Reference Werle, Mobli, DeWerff and Arneson2023). For instance, previous research in Wisconsin showed that several one-pass postemergence options from different sites of action could provide effective (>90%) giant ragweed control, but none of the selected herbicides provided effective waterhemp control at 14 d after application (Werle et al. Reference Werle, Mobli, DeWerff and Arneson2023). Crop injury is also a concern with some postemergence applications (Qasem Reference Qasem2011).

The two-pass herbicide strategy consists of a preemergence application fb a postemergence application designed for season-long broad-spectrum weed control to overcome weaknesses of one-pass preemergence or early postemergence-only strategies (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Liu, Peterson and Stahlman2021; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Soltani, Kaastra, Hooker, Robinson and Sikkema2019; Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Nurse, Gillard and Sikkema2013). Soltani et al. (Reference Soltani, Vyn and Sikkema2009) reported that one-pass preemergence or postemergence herbicides alone could control waterhemp by 41% to 94%; however, a preemergence fb postemergence herbicide strategy could consistently increase waterhemp control to 90% to 99%. However, a two-pass herbicide strategy may not fully address all the limitations associated with one-pass preemergence or one-pass postemergence application, and greater weed control and crop yield compared with a timely single-pass application may not always be the outcome. Adjusting and adopting the best herbicide strategy to manage the weed community within each field under unpredictable environmental conditions represents a major challenge for corn growers and their decision influencers (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Hager, Tranel, Davis, Martin and Williams2021; Severo Silva et al. Reference Severo Silva, Arneson, DeWerff, Smith, Silva and Werle2023). Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate multiple herbicide strategies, including one-pass preemergence, one-pass postemergence, preemergence fb postemergence, and preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual herbicide included across multiple locations with different weed spectrums representative of conventional tillage corn production systems in Wisconsin.

Materials and Methods

Site Description

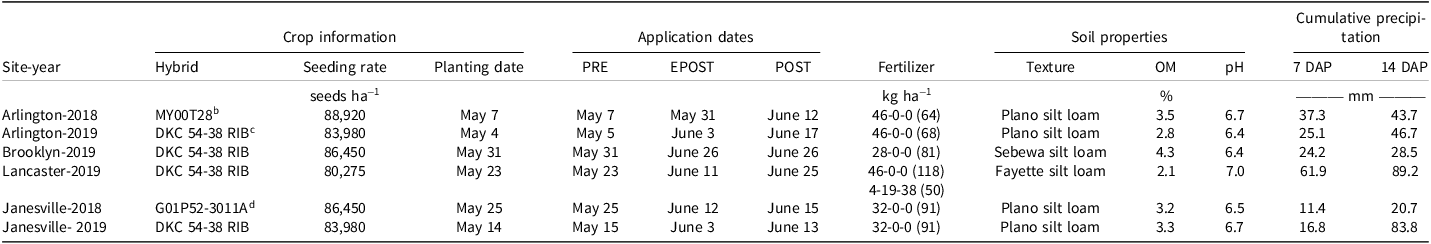

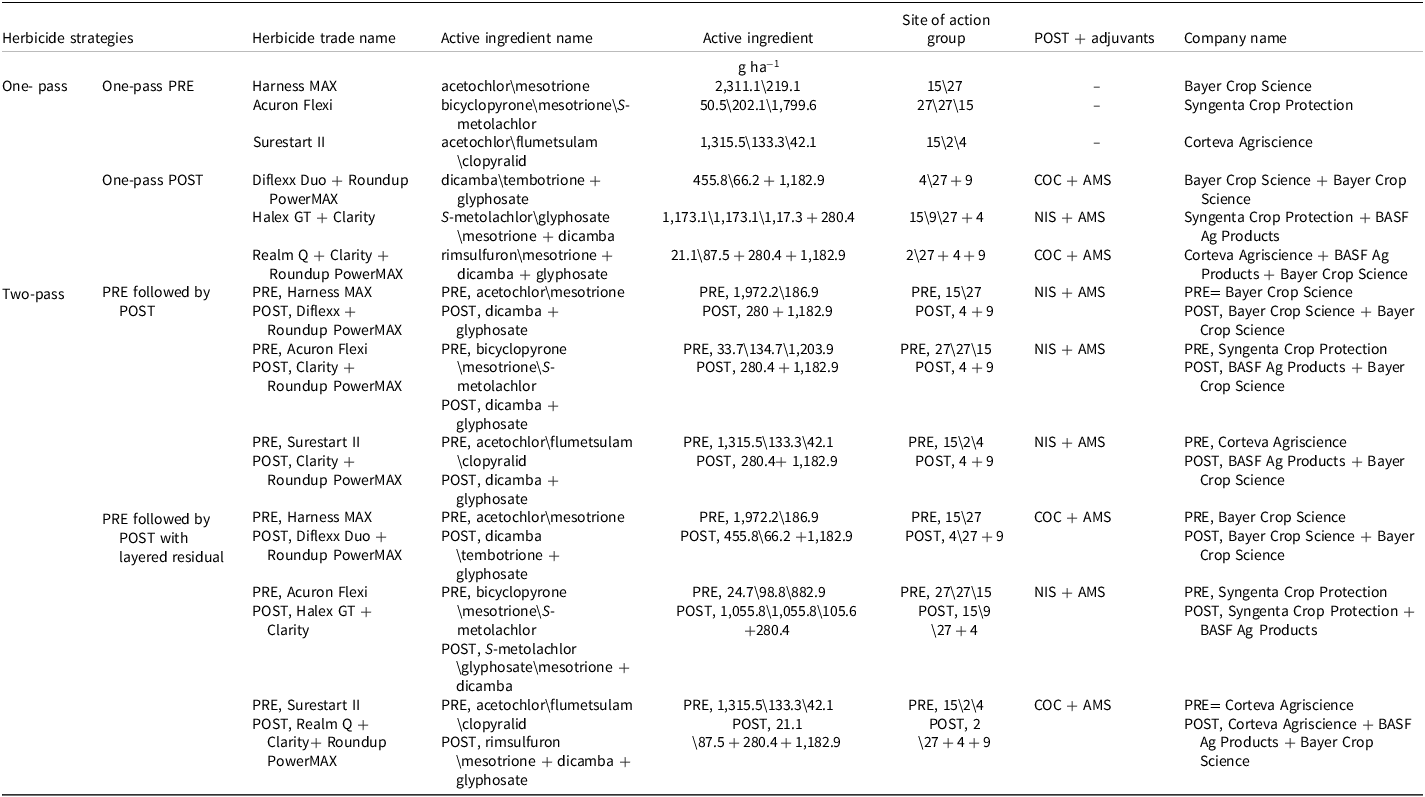

Field experiments were conducted over six site-years in 2018 and 2019 across four locations in southern Wisconsin under conventional tillage. In 2018 and 2019, field experiments were established at the Arlington Agricultural Research Station near Arlington, WI (Arlington-2018, Arlington-2019; 43.18°N, 89.20°W), and at the Rock County Farm near Janesville, WI (Janesville-2018, Janesville-2019; 42.43°N, 89.1°W). In 2019, two additional locations were added, one at a commercial farm located near Brooklyn, WI (Brooklyn-2019; 42.50°N, 89.22°W), and one at the Lancaster Agricultural Research Station near Lancaster, WI (Lancaster-2019; 42.49°N, 90.47°W). All experiments were established following a soybean crop the previous year and were tilled in the spring within 1 wk of corn planting, except Janesville-2018. There, the trial was established following corn the previous year and was chisel-plowed the previous fall and cultivated in the spring before corn planting. Further information regarding soil properties, crop establishment, and herbicide application for each site-year are presented in Table 1. Weeds were evenly distributed across the experimental area, and the weed demographics at each site-year was documented in the nontreated control (NTC) plots at the time of postemergence application (Table 2). The study was conducted as a factorial design of four herbicide strategies representing commonly adopted chemical weed control programs by Wisconsin corn growers (Mobli et al. Reference Mobli, DeWerff, Arneson and Werle2023; Werle and Oliveira Reference Werle and Oliveira2018) × three herbicide programs from different agrochemical companies plus an NTC for a total of 13 treatments (Table 3). All the herbicide strategies contained herbicides with residual activity and are commonly used in U.S. corn production (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Ward, Shaw, Llewellyn, Nichols, Webster, Bradley, Frisvold, Powles, Burgos, Witt and Barrett2012; Severo Silva et al. Reference Severo Silva, Arneson, DeWerff, Smith, Silva and Werle2023). The numerous herbicide programs available to Wisconsin corn growers preclude testing all possibilities. Thus, we selected three representative herbicide treatments within each herbicide strategy from different agrochemical companies. Three representative herbicide programs from different agrochemical companies were compared, and included four herbicide strategies: one-pass preemergence residual, one-pass early postemergence with residual, two-pass preemergence residual fb postemergence without residual, and two-pass preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual. The one-pass early postemergence with residual was applied when corn reached the V2 growth stage. The postemergence treatment for the two-pass herbicide strategies were applied when corn reached the V4/V5 growth stages. Atrazine was not included in the study due to its prohibition at two of the research sites (Arlington and Brooklyn) (DATCP 2023). Treatments were organized in a randomized complete block design with four replications. Plots were 3 m wide by 9.1 m long and consisted of four corn rows (76-cm row spacing). Herbicide products and rates for each system can be found in Table 3 and match the use pattern rates commonly adopted by corn growers in Wisconsin. All herbicides were applied using water as a carrier with a CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer calibrated to deliver 140 L ha−1 of spray solution. Turbo TeeJet 110015 nozzles (TeeJet Technologies, Glendale Heights, IL) were used for all herbicide treatments.

Table 1. Site information and soil properties from six site-years of a corn study conducted in Wisconsin in 2018 and 2019. a

a Abbreviations: DAP, days after planting; EPOST, early postemergence; OM, organic matter; POST, postemergence.

b Hybrid MY00T28 was a product of Mycogen, which at the time of experimental was Dow AgroSciences, and is now Corteva Agriscience.

c Hybrid DKC 54-38 RIB was a product of Decalb, which at the time of experimental was Monsanto, and is now Bayer CropScience.

d Hybrid G01P52-3011A is a product of Syngenta Crop Protection.

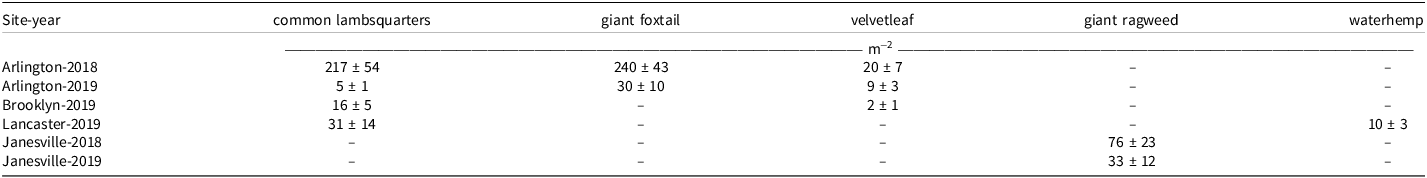

Table 2. Weed demographics in the nontreated control plots at the time of a postemergence application from six site-years.a,b

a Numbers are average ± standard error.

b A dash (–) indicates species not present at the specific site-year.

a Abbreviations: AMS, ammonium sulfate; COC, crop oil concentrate; NIS, nonionic surfactant; POST, postemergence; PRE, preemergence.

b Herbicide treatments included COC, 10 mL L−1; AMS 2,242 g ha−1; and NIS, 2.5 mL L−1.

c Herbicide application strategies are defined as follows: One-pass PRE means a one-pass PRE residual; One-pass POST means a one-pass early POST with residual; PRE followed by POST means a two-pass PRE residual followed by a postemergence without residual; and PRE followed by POST with layered residual means a two-pass PRE followed by a POST with layered residual.

Data Collection

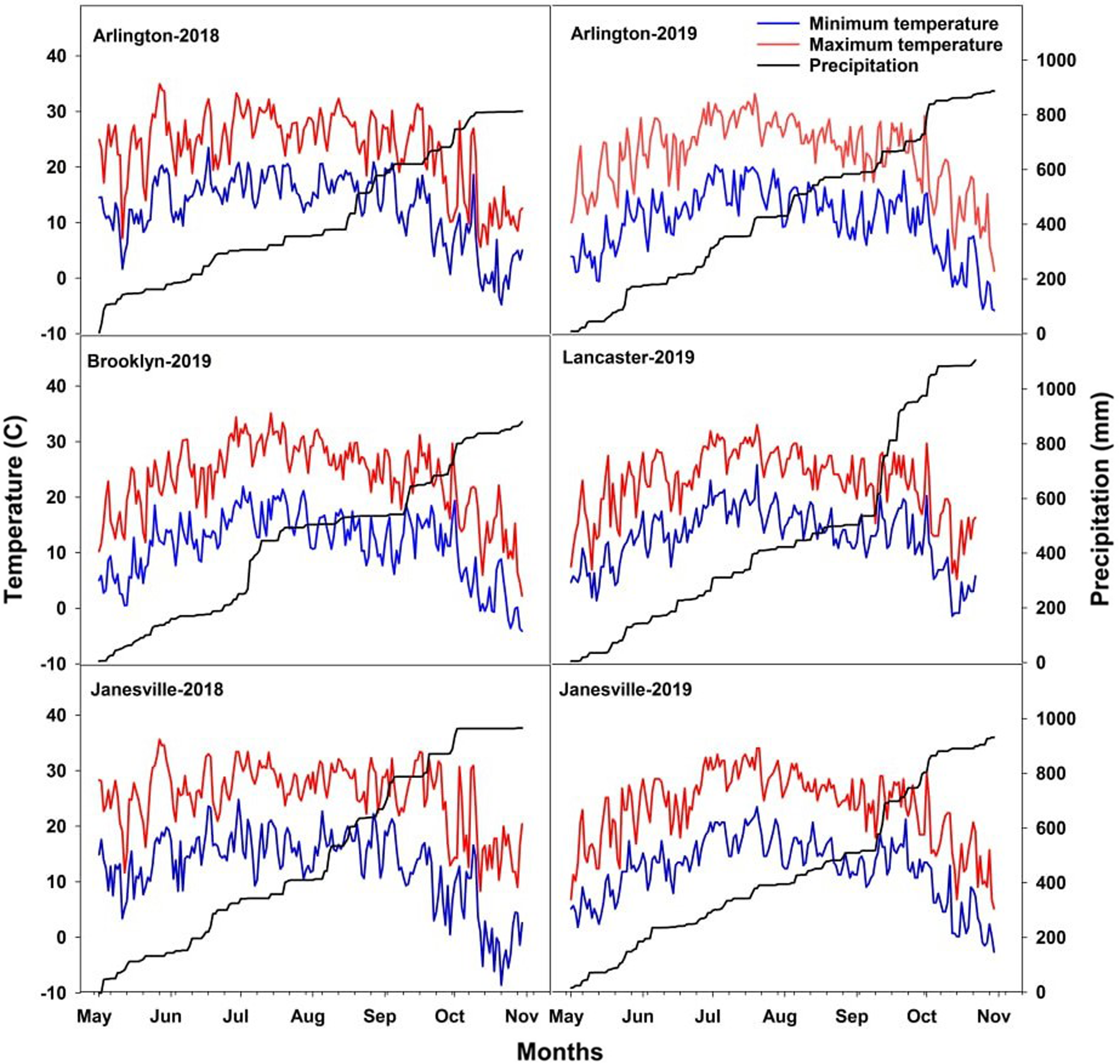

Daily minimum and maximum temperature and precipitation throughout the growing season were monitored at each site-year using on-site Watchdog 2000 Series weather stations (Figure 1). End-of-season overall weed control was visually rated on a scale of 0% (no control) to 100% (complete control) compared with the NTC within a week of corn harvest. A single overall rating across all weed species present was taken per plot (Boyd Reference Boyd2016). End-of-season weed biomass was also assessed within 7 d before corn harvest by placing a 1-m2 quadrat at a random location within the center two corn rows of each plot (Harker et al. Reference Harker, Clayton, O’Donovan, Blackshaw and Stevenson2004; O’Donovan et al. Reference O’Donovan, Harker, Clayton and Blackshaw2006). All weed species within the quadrat were clipped at the soil level and dry weight was determined by drying the samples in a forced-air oven at 54 C for 1 wk. Corn grain was harvested from the center two rows with a plot combine and yield data were adjusted to 15.5% grain moisture.

Figure 1. Daily maximum and minimum temperature and precipitation during each site-year.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses of variance were conducted for each site-year separately due to the different weed species composition and density at each experimental location using R statistical software (v. 4.2.1; R Core Team 2023). A significant interaction between site-year and herbicide strategy treatment was detected (P > 0.05), further supporting the decision to explore the results by site-year (data not shown). The normality and homogeneity of residual variance assumptions were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk and Breusch-Pagan tests, respectively, with the car statistics package. No transformation was necessary, and data analyses were conducted using the original dataset. Since our objective was not to evaluate these specific herbicide programs but to assess the broader question of herbicide strategy (one-pass preemergence residual, one-pass early postemergence with residual, two-pass preemergence residual fb postemergence without residual, and two-pass preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual), we treated these herbicide programs as random effects within the fixed effect of herbicide strategy (Hoverstad et al. Reference Hoverstad, Gunsolus, Johnson and King2004). ANOVAs were performed using the Anova.glmmTMB function from the glmm tmb package with a significance level of α = 0.05. Treatment means were compared using the grouping letters method with the emmeans and cld functions from emmeans (Lenth et al. Reference Lenth, Buerkner, Herve, Love, Riebl and Singmann2021) and multcomp (Hothorn et al. Reference Hothorn, Bretz and Westfall2008) packages, respectively. Herein, weed control results are also discussed based on “effective control” (>90% control combined across species; Mobli et al. Reference Mobli, DeWerff, Arneson and Werle2023).

Results and Discussion

The amount of precipitation within 14 d after planting varied from 21 to 89 mm across the site-years (Table 1), and all site-years received more than 900 mm of rainfall throughout the growing season (Figure 1). Landau et al. (Reference Landau, Hager, Tranel, Davis, Martin and Williams2021) reported that adequate rainfall after application enhances the probability of effective weed control with soil-applied residual herbicides. In the current study, adequate precipitation at all site-years favored activation of soil residual herbicide treatments applied early season.

Arlington-2018

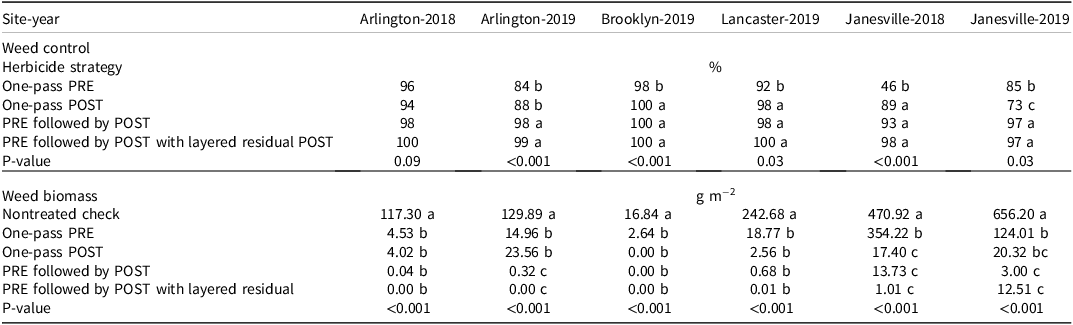

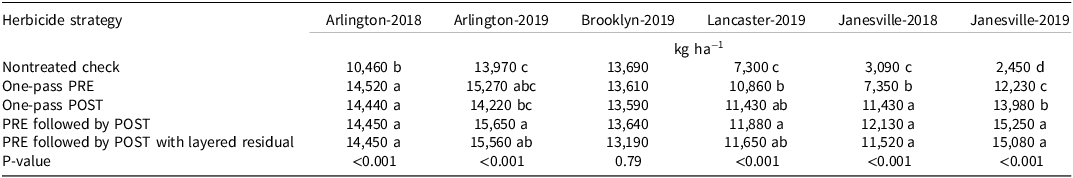

A high density of common lambsquarters (217 ± 54 m−2) and giant foxtail (240 ± 43 m−2), and a moderate density of velvetleaf (20 ± 7 m−2) was present at Arlington-2018 in the NTC plots at the time of postemergence application (Table 2). The herbicide strategy main effect was not significant (P < 0.05) on overall weed control, but it was significant (P < 0.001) for weed biomass and corn yield (Tables 4 and 5). All herbicide strategies provided effective (>90%) overall weed control, and no weed biomass differences were observed across approaches (0.0 to 4.5 g m−2) compared with the NTC (117.3 g m−2; Table 4). Corn yield from the NTC (10,460 kg ha−1) was reduced by 28% compared with the average corn yield of 14,464 kg ha−1 from herbicide-treated corn with different strategies, and no yield differences were observed across herbicide strategies themselves (Table 5).

Table 4. Overall end-of-season weed control and weed biomass across different herbicide strategies for each site-year.a,b,c

a Abbreviations: POST, postemergence; PRE, preemergence.

b Letters indicate group differences between means of treatments (LSD, α = 0.05).

c Herbicide application strategies are defined as follows: One-pass PRE means a one-pass PRE residual; One-pass POST means a one-pass early POST with residual; PRE followed by POST means a two-pass PRE residual followed by a postemergence without residual; and PRE followed by POST with layered residual means a two-pass PRE followed by a POST with layered residual.

a Abbreviations: POST, postemergence; PRE, preemergence.

b Letters show group differences between means of treatments (LSD, α = 0.05).

c Herbicide application strategies are defined as follows: One-pass PRE means a one-pass PRE residual; One-pass POST means a one-pass early POST with residual; PRE followed by POST means a two-pass PRE residual followed by a postemergence without residual; and PRE followed by POST with layered residual means a two-pass PRE followed by a POST with layered residual.

Arlington-2019

At this site-year in the NTC plots at the time of postemergence application, common lambsquarters (5 ± 1 m−2), giant foxtail (30 ± 10 m−2), and velvetleaf (9 ± 3 m−2) were present at low to moderate density (Table 2). The effect of herbicide strategy was significant (P < 0.001) on overall weed control, weed biomass, and corn yield (Tables 4 and 5). Two-pass strategies of preemergence fb postemergence (98%) and preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual (99%) herbicide applications resulted in the greatest overall weed control and least weed biomass (0.3 and 0.0 g m−2, respectively). Herbicide strategies with only a one-pass preemergence (84%) or a postemergence (88%) application were not sufficient for effective overall weed control. Similarly, Lindsey et al. (Reference Lindsey, Everman, Chomas and Kells2012) found that a one-pass postemergence strategy was not a sound approach to managing fields with a high infestation of giant foxtail, whereas effective overall season-long control could be achieved by a preemergence fb a postemergence application with a lower risk of corn yield reduction. In the current study, no significant differences in corn yield were observed among the preemergence fb postemergence (15,650 kg ha−1), preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual (15,560 kg ha−1), and one-pass preemergence (15,270 kg ha−1) strategies. Corn yield was 9% lower from the one-pass postemergence strategy (14,220 kg ha−1) compared with the preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual strategy (15,560 kg ha−1), whereas yield for the latter strategy was comparable to that of the one-pass preemergence (15,270 kg ha−1) and preemergence fb postemergence (15,650 kg ha−1) strategies. Corn yield from the NTC (13,970 kg ha−1) was reduced by 11% compared with yield from the preemergence fb postemergence strategy.

Brooklyn-2019

At this site-year in the NTC plots at the time of postemergence application, common lambsquarters (16 ± 5 m−2) and velvetleaf (2 ± 1 m−2) were present at low density (Table 2). The effect of herbicide strategy was significant (P < 0.001) on overall weed control and weed biomass (Tables 4). All herbicide strategies provided effective (>90%) overall weed control, and no weed biomass differences were observed across strategies themselves (0.0 to 2.6 g m−2) compared with the NTC (16.8 g m−2; Table 4). Herbicide strategy was not significant (P = 0.79) on corn yield (average 13,542 kg ha−1; Table 5). Werner et al. (Reference Werner, Curran, Harper, Roth and Knievel2004) reported that low velvetleaf density can lead to significant corn yield loss, and its abundant seed production and longevity may affect future weed control decisions. Stephenson and Bond (Reference Stephenson and Bond2012) reported season-long effective (>90%) velvetleaf control with one-pass preemergence or one-pass postemergence applications in experimental fields with moderate velvetleaf infestation (10 to 20 plants m−2). Therefore, although velvetleaf in low to moderate density can be relatively easy to control with either a one- or two-pass herbicide strategy, proper control of established plants should not be neglected.

Lancaster-2019

At this site-year in the NTC plots at the time of postemergence application, common lambsquarters (31 ± 14 m−2) and waterhemp (10 ± 3 m−2) were present at a moderate density (Table 2). The effect of herbicide strategy was significant on overall weed control (P = 0.03), weed biomass (P < 0.001) and corn yield (P < 0.001; Tables 4 and 5). All herbicide strategies provided effective (>90%) overall weed control, and no significant differences in weed biomass (0.1 to 18.8 g m−2) were observed among the strategies when compared with the NTC (242.7 g m−2; Table 4). No differences were observed in corn yield among the preemergence fb postemergence (11,880 kg ha−1), preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual (11,650 kg ha−1), and one-pass postemergence (11,430 kg ha−1) strategies (Table 5). Corn yield from NTC plots (7,300 kg ha−1) was reduced by 39% and by 9% from one-pass preemergence (10,860 kg ha−1) plots compared with plots that received the preemergence fb postemergence strategy.

Waterhemp (10 ± 3 m−2) was present only at Lancaster-2019, along with common lambsquarters. While additional site-years of data are needed, the research presented here demonstrates that effective weed control of waterhemp and common lambsquarters can be achieved using various herbicide strategies that incorporate effective soil residual and foliar herbicides that act on multiple sites of action in corn. Previous research conducted in Wisconsin demonstrated that a one-pass postemergence application with a single site-of-action herbicide could not provide effective (>90%) foliar waterhemp control 14 d after application (Werle et al. Reference Werle, Mobli, DeWerff and Arneson2023). In contrast, herbicides that act on than one site of action in either a one-pass preemergence (Severo Silva et al. Reference Severo Silva, Arneson, DeWerff, Smith, Silva and Werle2023) or a one-pass postemergence (Willemse et al. Reference Willemse, Soltani, Benoit, Jhala, Hooker, Robinson and Sikkema2021) application could effectively control waterhemp (>90%). Moreover, Skelton et al. (Reference Skelton, Ma and Riechers2016) found that under drought stress conditions, the efficacy of using chemicals to control waterhemp was reduced due to decreased foliar uptake and translocation of herbicides. Therefore, besides herbicide strategies, weed composition, weed herbicide-resistance status, and environmental conditions during and following application should be taken into consideration when developing a weed control program.

Several one-pass preemergence and one-pass postemergence herbicide options are available for effective common lambsquarters control in corn (Chomas and Kells Reference Chomas and Kells2004; Jha et al. Reference Jha, Kumar, Garcia and Reichard2015; Metzger et al. Reference Metzger, Soltani, Raeder, Hooker, Robinson and Sikkema2018). In the present study, common lambsquarters was present in combination with other species at all research sites except Janesville-2018 and -2019. Except for one-pass preemergence (84%) and one-pass postemergence (88%) applications in Arlington-2019, all herbicide strategies provided effective (>90%) overall weed control (common lambsquarters, giant foxtail, velvetleaf, or waterhemp) regardless of their densities. Therefore, the herbicide strategy was not as influential for the site-years infested with common lambsquarters, giant foxtail, velvetleaf, and/or waterhemp species.

Janesville-2018

A high density of giant ragweed (76 ± 23 m−2) was present at this site-year in the NTC plots at the time of postemergence application (Table 2). The effect of herbicide strategy was significant (P < 0.001) on weed control, weed biomass, and corn yield (Tables 4 and 5). The one-pass preemergence strategy provided the least weed control (46%) and most weed biomass (354.2 g m−2) compared with other herbicide strategies (<17.4 g m−2). Otherwise, no differences were observed among the herbicide strategies on weed control (89% to 98%) and weed biomass (1.0 to 17.4 g m−2; Table 4). There were no differences in corn yield among preemergence fb postemergence (12,130 kg ha−1), preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual (11,520 kg ha−1), and one-pass postemergence (11,430 kg ha−1) strategies (Table 4). In the one-pass preemergence strategy, corn yield (7,350 kg ha−1) was 39% lower than from the preemergence fb postemergence (12,130 kg ha−1) strategy. Corn yield (3,090 kg ha−1) from the NTC was reduced by 75% compared with yield from the preemergence fb postemergence strategy.

Janesville-2019

A moderate giant ragweed (33 ± 12 m−2) density was present at this site-year in the NTC plots at the time of postemergence application (Table 2). Herbicide strategy had a significant (P < 0.001) effect on weed control, weed biomass, and corn yield (Tables 4 and 5). One-pass preemergence and one-pass postemergence herbicide strategies provided 73% and 85% weed control, respectively, while the preemergence fb postemergence (97%) and preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual (97%) strategies provided effective (>90%) weed control. Weed biomass (124.0 g m−2) was greater after a one-pass preemergence application than other herbicide strategies (<20.3 g m−2). Except for the one-pass preemergence application, no differences in weed biomass were observed among the herbicide strategies. No differences in corn yield were observed between the preemergence fb postemergence (15,250 kg ha−1) and preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual (15,080 kg ha−1) strategies, and corn yield was higher after these two strategies than a one-pass preemergence or a one-pass postemergence herbicide strategy (Table 5). Corn yield from the NTC (2,450 kg ha−1) was reduced by 84% compared with yield from the preemergence fb postemergence approach (15,250 kg ha−1).

In the Midwest, giant ragweed is one of the most difficult weeds to control in conventional tillage corn production systems due to its extended emergence pattern (late April to mid-July), rapid growth, and high plasticity (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Clay, Cardina, Dille, Forcella, Lindquist and Sprague2013; Ganie et al. Reference Ganie, Sandell, Jugulam, Kruger, Marx and Jhala2016; Glettner and Stoltenberg Reference Glettner and Stoltenberg2015; Striegel et al. Reference Striegel, Oliveira, DeWerff, Stoltenberg, Conley and Werle2021). Soltani et al. (Reference Soltani, Shropshire and Sikkema2011) reported that a one-pass preemergence application resulted in ineffective control of giant ragweed (12% to 83%), whereas the one-pass postemergence strategy was more effective, providing 60% to 94% control of giant ragweed 28 d after herbicide application. In the current study, giant ragweed was present at Janesville-2018 (76 ± 23 m−2) and Janesville-2019 (33 ± 12 m−2). Regardless of giant ragweed infestation level, in both site-years, one-pass preemergence (46% to 85%) or one-pass postemergence (73% to 89%) strategies did not provide effective end-of-season weed control, whereas preemergence fb postemergence and preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual strategies did, resulting in 93% to 98% end-of-season weed control. Therefore, to minimize corn yield loss due to giant ragweed interference and diminish further weed seedbank replenishment, the implementation of two-pass herbicide strategies is recommended.

Effective season-long chemical weed control depends on multiple factors such as environmental conditions (precipitation, temperature), herbicide chemistry (half-life, dissipation rate), edaphic conditions (texture, pH, organic matter), and weed community composition (Varanasi et al. Reference Varanasi, Prasad and Jugulam2016; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Zuo, Li, Guo, Liu and Wang2017). Weed resistance and/or herbicide misapplication contributes to chemical weed management failure, even when all the aforementioned conditions should favor chemical weed management (Taberner Palou et al. Reference Taberner Palou, Cirujeda Ranzenberger and Zaragoza Larios2008). Corn growers may find it difficult to design an effective herbicide strategy, especially when they must manage troublesome weed species under high infestation levels and insufficient precipitation for activation of soil residual herbicides. This study demonstrates that weed interference could reduce corn yield by 11% to 75% depending on weed community composition. The two-pass preemergence fb postemergence and preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual strategies provided the greatest end-of-season weed control and corn yield across all site-years, regardless of weed demographics and environmental conditions (Tables 4 and 5). Lastly, corn is often rotated with soybean across midwestern states where growers are having a difficult time managing herbicide-resistant weeds in rotation years when soybean is grown. Yadav et al. (Reference Yadav, Jha, Hartzler and Liebman2023) reported that effective weed control (≥90%) with multiple herbicides in the corn year improved weed control during the subsequent soybean season. Growers should take advantage of numerous preemergence and postemergence herbicide options available during corn years to design effective herbicide programs to enhance overall weed management within their cropping systems (Kohrt and Sprague Reference Kohrt and Sprague2017; Yadav et al. Reference Yadav, Jha, Hartzler and Liebman2023). Although this study provides valuable insights into chemical weed management using various herbicide strategies across six site-years with diverse weed community compositions representative of Wisconsin conventional tillage corn production systems, it is important to note that all site-years received adequate precipitation throughout the growing season (>900 mm), which favored herbicide activity, particularly of soil residual herbicides. Therefore, it would be beneficial to evaluate the selected herbicide strategies under dry growing seasons because more variable precipitation is expected in the future, which can affect the performance of chemicals in weed control (Landau et al Reference Landau, Hager, Tranel, Davis, Martin and Williams2021).

Practical Implications

Results of the present study can help growers and their decision influencers better design herbicide strategies and programs for conventional tillage corn production systems based on known weed community composition within each of their managed fields. Herbicide costs were not evaluated in this research and should be taken into consideration when deciding the best strategy and product composition. Results of the current study demonstrate that weed species such as common lambsquarters and velvetleaf can be properly controlled by effective one-pass preemergence, one-pass postemergence, preemergence fb postemergence and preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual herbicide strategies. However, for more troublesome weeds such as giant ragweed, a two-pass herbicide strategy was required for effective control (preemergence fb postemergence and preemergence fb postemergence with layered residual). Therefore, it is advisable to adopt a two-pass herbicide strategy to ensure the successful suppression of troublesome weeds throughout the growing season, particularly when faced with high weed pressure and unpredictable environmental conditions.

Acknowledgements

We thank staff members at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arlington and Lancaster Agricultural Research Stations, and the Rock County Farm for supporting this research. We also thank the members of the UW-Madison Cropping Systems Weed Science program for their technical support with the field experiments.

Funding statement

This study was partially funded by the Wisconsin Corn Growers Association.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.